Argentina

Basic Data

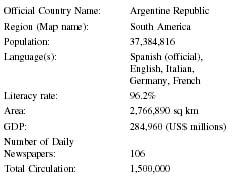

| Official Country Name: | Argentine Republic |

| Region (Map name): | South America |

| Population: | 37,384,816 |

| Language(s): | Spanish (official), English, Italian, Germany, French |

| Literacy rate: | 96.2% |

| Area: | 2,766,890 sq km |

| GDP: | 284,960 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Daily Newspapers: | 106 |

| Total Circulation: | 1,500,000 |

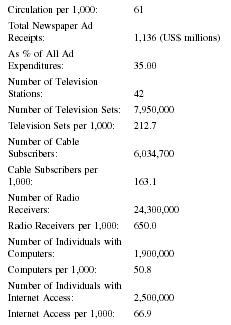

| Circulation per 1,000: | 61 |

| Total Newspaper Ad Receipts: | 1,136 (US$ millions) |

| As % of All Ad Expenditures: | 35.00 |

| Number of Television Stations: | 42 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 7,950,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 212.7 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 6,034,700 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 163.1 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 24,300,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 650.0 |

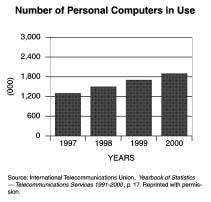

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 1,900,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 50.8 |

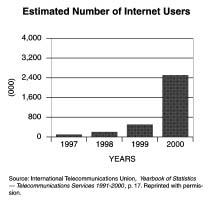

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 2,500,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 66.9 |

Background & General Characteristics

Argentina is the second largest country in Latin America after Brazil, with a total area of 2.8 million square kilometers. It is a federal republic made up of 23 provinces and the city of Buenos Aires, home of the federal government. The total population according to the 2000 national census is 36 million, of which 13 million live in the city of Buenos Aires and surrounding suburbs. Argentines are Spanish speakers, mostly Catholic (around 87 percent of population; 35 percent practicing), have a very high literacy rate (96 percent of population), and a fairly large middle class. The country's gross domestic product (GDP) in 2001 was $281 billion and per capita GDP was $7,686. At the end of 2001, the country entered a severe economic crisis that led to a sharp depreciation of the currency (previously pegged to the dollar), a high increase in the unemployment rate to 23 percent as of July 2002, a banking crisis that included the freezing of individual accounts, and the fall of two presidents in just a few weeks.

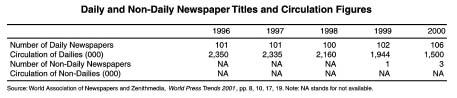

Argentines are avid readers of newspapers, having the highest newsprint consumption in Latin America according to UNESCO. Data on newspaper circulation differs

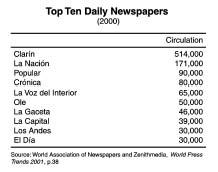

The 10 largest national newspapers—which may vary depending upon the source referenced—are: Clarín (800,000 circulation; 1.2 million on Sundays); La Nación (500,000 circulation; 800,000 on Sundays); Ámbito Financiero (300,000 circulation); Crónica (300,000 circulation); Diario Popular (300,000 circulation); Página 12 (150,000 circulation); La Prensa (120,000 circulation); El Cronista (100,000 circulation); Buenos Aires Herald (100,000 circulation); and Olé (100,000 circulation).

The most influential national newspapers are Clarín and La Nación, both based in the city of Buenos Aires. The one with the highest circulation in the country is Clarín, founded by Roberto Noble in 1945. It is considered the most widely read newspaper in Spanish-speaking Latin America. It belongs to a multimedia conglomerate that owns two radio stations ( Mitre and FM100), two television channels (cable channel Multicanal and open air Canal 13 ), the newspaper Olé (the only major daily dedicated entirely to sports news), and shares in at least three provincial papers as well as in the news agency DYN. It employs approximately 900 people and

The second largest paper, La Nación was founded in 1870 and has been one of the most influential newspapers in the country's history. It has 500 employees and has bureaus all over the country. La Nación owns parts of the main national company dedicated to the commercialization of newsprint and has shares in at least two provincial dailies and in the news agency DYN. In the last few years it has invested over $100 million in the modernization of its operating plant, including color editions and faster printing mechanisms. On weekdays it has on average 18 pages in its main section, and 8 additional pages for regular supplements. On Sundays it has 24 pages in its main section in addition to special supplements and a magazine. La Nación is considered to have a center-right editorial position.

The newspapers Ámbito Financiero and El Cronista are the largest ones dedicated to economic issues. They are considered the best source for daily financial activity and analysis of the local markets, including articles by well-known economists. Neither one is published on Sundays. Ámbito Financiero owns a smaller newspaper, La Mañana del Sur, that is sold in three southern provinces. It has innovated by establishing plants in the interior of the country to speed up the publishing process and improve circulation. El Cronista was founded in 1908 and was one of the largest and most influential newspapers in the decades between 1930 and 1950. Its editorial opposition to the last military government (1976-83) generated numerous threats to its journalists, including the kidnapping and "disappearance" of its director, Raúl Perrota. Since the year 2000 El Cronista is wholly owned by the media group Recoletos from Spain, which is itself owned by the Pearson Group, editor of the Financial Times.

The newspapers Diario Popular and Crónica are considered sensationalists and are known to compete for the same readership, which comes mostly from the popular sectors. The first one is a left-leaning paper that emphasizes crime and catastrophic news and includes supplements for the suburbs of Buenos Aires, where it is published. The second one is a nationalist paper with an anti-U.S. and anti-England perspective (particularly following the 1982 war with England), and it is published in three daily editions.

The main leftist newspaper in Argentina is Página 12, which began its publication in 1987 and rapidly gained a niche within the intellectual and progressive readership. Página 12 has been consistently critical of government policy. Many well-known leftist intellectuals and journalists contribute or have worked for this newspaper. It has an innovative style, mixing humor and irony with a literary flair in covering the news. On weekdays it has an average of 36 pages. The newspaper includes weekend supplements on culture, media, economics, and foreign affairs.

The only major foreign language newspaper is the Buenos Aires Herald, founded in 1876 and published in that city. It is written in English with editorials in both English and Spanish. It played an opposition role to the military government that ruled Argentina between 1976 and 1983, which led to recurring threats that resulted in its editor, Graham Yoll, leaving the country in exile.

The provinces of Argentina, where more than half of the country's population lives, are home to several newspapers that provide a wealth of local news. According to the Argentine Association of Newspapers from the Interior (ADIRA), provincial newspapers, with 90 percent of the share, dominate the newspaper market outside the city of Buenos Aires and surrounding metropolitan area. The four largest provinces are those of Buenos Aires, Cordoba, Santa Fe, and Mendoza. In the province of Buenos Aires, where the large cities of La Plata and Mar del Plata are located, there are about 150 newspapers; in Cordoba, home of the second biggest city in the country, there are at least 16 newspapers, including the biggest regional newspaper in the country, La Voz del Interior founded in 1904. In Santa Fe there are 12 newspapers, and in Mendoza there are three newspapers of which Los Andes, founded in 1882, is the most important.

The smaller province of Entre Rios has a large number of newspapers, at least 22, but the most famous one is Hora Cero. The province of La Pampa has 3 newspapers, including one of the oldest in the country, La Arena, founded in 1900. Another provincial newspaper with a long history is La Gaceta from Tucumán, founded in 1912. The province of Santa Cruz is the home of at least 9 local newspapers; the provinces of Chubut and Tierra del Fuego have 7 newspapers each; the province of Formosa has 6; Rio Negro has 5; the provinces of Corrientes, Jujuy, Misiones, and San Juan have 4 newspapers each; Catamarca, Chaco, La Rioja, Salta, Santiago del Estero, and San Luis have 2 newspapers each; and the province of Neuquen has only one big local newspaper.

The history of the press in Argentina is deeply intertwined with the rich and convoluted history of that land. Its origins can be traced back to colonial times. The first newspaper edited in what is now Argentina was La Gazeta, a monthly publication of eight pages that began in the year 1764. During the first decades of the following century several publications began to propagate the ideas of the independence movement, such as the Correo de Comercio or La Gazeta de Buenos Ayres. Some others like the Redactor del Congreso Nacional had an important historical role in publishing the transcripts of the convention that declared independence in 1916. In the years that followed independence, the antagonist relations between the port city of Buenos Aires and the interior, which eventually evolved into a civil war, promoted the emergence of various provincial newspapers such as La Confederación from the province of Santa Fe. Under the control of Governor Rosas (1829-32; 1835-52) from the province of Buenos Aires, we find the first period of widespread censorship, including the closing of newspapers and the killing of several journalists critical of the government.

The period of peace and growth following the civil war begins in 1870. It is at this time that La Nación and La Prensa, contemporary newspapers, began their publication. President Bartolome Mitre founded La Nación. During the decade of the 1880s, coinciding with Argentina's frontier wars, many newspapers with high nationalist, militaristic, and expansionist content began to be published. In the 1920s the new press tended to be run by some of the conservative forces in control of the government. At that time newspapers like El Cronista and Noticias Gráficas began to be published. In the year 1945, when Juan Peron entered the political scene, several newspapers of more populist tendencies were initiated, including today's largest newspaper Clarín. President Peron (1946-52; 1952-55) exerted strong pressure against

Economic Framework

As of mid-2002, after four years of recession and a drastic financial crisis, the short-and medium-term economic prospects for media corporations, as well as for most other businesses, seem bleak. Newspapers have recently hiked prices by at least 20 percent (to $1.20 pesos), pressured by a corresponding drop of about 50 percent in advertising demand. Financial difficulties have also led national newspapers to reduce their personnel by almost 20 percent and to undertake a general reduction of salaries. The situation of the two largest newspapers, Clarín and La Nación, is particularly difficult because in recent years they proceeded with a series of investments that required substantial capital, which led them to acquire large dollar debts. These liabilities in foreign currency became major a problem after the Argentine peso depreciated sharply to less than one-third of its previous value within the first six months of 2002.

In light of the serious financial situation faced by the local news media, Congress is debating a law limiting the share of foreign companies in cultural enterprises. According to the bill, foreigners will have a 20 percent limit in the share of national media companies. The purpose of the new law is to prevent foreign companies from capturing a local market, where many companies face serious cash shortages and are near bankruptcy. One big newspaper, La Prensa, which had a circulation short of 100,000, has recently started free distribution, hoping to increase readership and advertising revenue.

Newspapers from the interior of the country were also hit hard in recent times. Not only did the increasing costs of foreign imports and the freezing of local credit hurt them, but they also had to suffer a 100 percent increase in the price of newsprint (mostly of national origin). The organization that brings together these provincial newspapers (ADIRA) has recently called for the mobilization of journalists in defense of what they see as a threatened profession.

In the year 2000 the government of Fernando de La Rua was facing a serious budget deficit and decided to increase the value added tax applied to cable television from 10.5 percent to 21 percent, an increase that was not extended to print media. The Inter-American Press Society (SIP) recently asked the Argentine government to abolish the added value tax on newspapers given the tenuous financial situation of the press and the excessive burden of the rates in place. The same source accused the government of having the highest tax rates in the region.

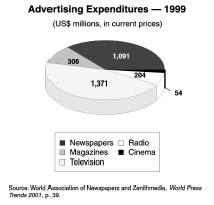

According to the press organization FLAPP ( Federación Latinoamericana de Prensa en Periódicos ), advertising revenue during the year 2001 was approximately $2.8 billion. Half of that advertising money is spent on television, 37 percent is spent in newspapers, almost 5 percent in magazines, over 6 percent in radio, and the rest in newspaper supplements. Although figures have not been released yet, there is a consensus that investment in advertising dropped significantly in 2002.

Ownership of media companies is fairly concentrated. This has generated numerous complaints and threats of new regulations, but in practice Congress has been reluctant to pass new legislation. The " Clarín Group " is the biggest conglomerate, controlling the newspaper of the same name in addition to shares in two major provincial newspapers, the sports daily Olé, cable channel Multicanal, open air channel Canal 13, radio Mitre, radio FM100, part of the news agency DYN, the press Artes Gráficas Rioplatense S.A., the publishing company Aguilar, the magazine Elle, the TV studio Buenos Aires Television, and other investments, such as a cellular company in the interior of the country.

The second largest media company is La Nación S.A., which runs the newspaper of the same name and is partial owner of the national satellite Paracomstat. The two major groups are associated in several commercial ventures. In 1978 they started Papel Prensa S.A. with the goal of producing newsprint. The company now produces 165,000 tons of paper a year, covering a major part of the local market. Both groups are also partners with the Spanish "Correo Group" in a company called CIMECO, which owns the regional newspapers La Voz del Interior and Los Andes, each one dominant in their local markets (83 percent and 73 percent of provincial circulation respectively). Clarín Group and La Nación S.A. also have shares in the news agency DYN.

Argentina has three other important media groups also located in the city of Buenos Aires: Atlántida Press, Crónica Group, and Ámbito Financiero Group. The editorial group Atlántida has been an important player in the magazine business for several decades. It owns eight magazines (El Gráfíco, Gente, Teleclic, Para Ti, Chacra, Billiken, Plena, and Conozca Más ), part of a TV channel Telefé, and radio stations Continental and FM Hit. The group Crónica has, in addition to the newspaper of the same name, the magazines Flash and Ahora, the TV news channel Crónica TV, the television studio Estrella, and the newspaper El Atlántico from the biggest coastal city, Mar del Plata. The group controlling Ámbito Financiero also publishes the Patagonian newspaper, Mañana delSur, and owns a TV channel in the province of Rio Negro. Another major consortium led by Eduardo Eurnekian (owner of radio stations America and Aspen) had been a major player in the media business until recently, but it has recently sold off its shares in the television stations America 2 and Cablevisión and the newspaper El Cronista (to a Spanish company). A new upstart player includes the group led by journalist Daniel Hadad, who runs the financial newspaper Buenos Aires Económico, a radio station, and the television channel Azul TV.

In the interior of the country we find several smaller media groups built around local newspapers. The group El Día in the city of La Plata publishes the newspaper of the same name in addition to the national newspapers Diario Popular and the news agency NA. The group Nueva Provincia from the city of Bahia Blanca has the newspaper of the same name, the magazine Nueva, and shares in the national television channel Telefé and in a local FM station. The group Supercanal from the province of Mendoza controls the newspaper Uno in addition to a television channel and at least three radio stations. The group Territorio from the province of Misiones owns the newspaper of the same name and the cable company in the provincial capital. In the province of Salta the group El Tribuno has the newspaper of the same name, which is also popular in the province of Jujuy, and shares in local TV channels. The group Rio Negro from Rio Negro province owns the newspaper of the same name and the provincial cable channel. The groups Territorio, El Tribuno, and Rio Negro also have shares in the news agency DYN.

Antitrust legislation was passed in 1997 under the name "Law to Defend Competition." It restricts and regulates monopolies or oligopolies across the country as well as determines the possible merging of different companies. The law provides monetary fines, penalties, and even jail sentences for those found breaking it. This legislation mandated the creation of a National Commission to Defend Competition, an agency independent of the executive branch. Because most of the large media conglomerates were created in the years after deregulation in 1991 and prior to this law, they cannot be forced to dismember now, but future mergers need to correspond to the regulations of the new law.

The two main workers' organizations in the press are the Buenos Aires Press Workers Union (UTPBA) and the Argentine Federation of Press Workers (FATPREN), itself a national labor organization composed of over 40 individual unions. Industrial relations have been difficult, particularly over the reform of severance packages and the deregulation of the health funds run by the unions. Since the health fund system opened up, many press workers have left the poorly performing press union fund for other competing organizations, reducing an important source of revenues and political power. Unions provide individual journalists with legal counseling in case of conflict with management or in judicial matters.

Sometimes union disputes have become violent. In May of 2000 several armed groups invaded eight distribution centers for the provincial newspaper La Gaceta from Tucumán, hitting employees and burning the Sunday edition of the paper. Many reports associated the incident with an internal conflict. The newspaper had been involved in a labor dispute with members representing the street newspaper vendors ( canillitas ) over the reduction of commissions given to the workers. However, there was no judicial finding on whether the incident related to such a dispute, or if it was in response to other crime-related news published in the paper.

Press Laws

The constitutional reforms of 1994 incorporated several provisions upholding freedom of expression and codifying state-press relations. Article 14 of the Constitution establishes that all inhabitants of the Argentine Republic have the right to "publish their ideas in the press without prior censorship…" and Article 32 specifies that… "The federal Congress cannot not pass laws that limit freedom of the press or that establish over them a federal jurisdiction." The right to confidential press sources is specifically protected by constitutional Article 43. Article 75 section 19 of the same Constitution gives Congress the power to regulate broadcasting media.

Argentina has incorporated into the Constitution several international treaties that deal specifically with press rights. A document that has been important in cases related to freedom of the press is the American Convention on Human Rights or "Pact of San José, Costa Rica," which establishes the following rights:

Article 13. Freedom of Thought and Expression

- 1. Everyone has the right to freedom of thought and expression. This right includes freedom to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing, in print, in the form of art, or through any other medium of one's choice.

- 2. The exercise of the right provided for in the foregoing paragraph shall not be subject to prior censorship but shall be subject to subsequent imposition of liability, which shall be expressly established by law to the extent necessary to ensure: (a) respect for the rights or reputations of others; or (b) the protection of national security, public order, or public health or morals.

- 3. The right of expression may not be restricted by indirect methods or means, such as the abuse of government or private controls over newsprint, radio broadcasting frequencies, or equipment used in the dissemination of information, or by any other means tending to impede the communication and circulation of ideas and opinions.

- 4. Notwithstanding the provisions of paragraph 2 above, public entertainments may be subject by law to prior censorship for the sole purpose of regulating access to them for the moral protection of childhood and adolescence.

- 5. Any propaganda for war and any advocacy of national, racial, or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to lawless violence or to any other similar action against any person or group of persons on any grounds including those of race, color, religion, language, or national origin shall be considered as offenses punishable by law.

Article 14. Right of Reply

- 1. Anyone injured by inaccurate or offensive statements or ideas disseminated to the public in general by a legally regulated medium of communication has the right to reply or to make a correction using the same communications outlet, under such conditions as the law may establish.

- 2. The correction or reply shall not in any case remit other legal liabilities that may have been incurred.

- 3. For the effective protection of honor and reputation, every publisher and every newspaper, motion picture, radio, and television company, shall have a person responsible who is not protected by immunities or special privileges.

In the year 1992 the president of the country, Carlos Menem, filed a suit against journalist Horacio Vertbisky for desacato —in this case disrespect to the president of the country—a common restriction to press freedom across many countries in Latin America. The journalist took the case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights ( CIDH ), who ruled in favor of Vertbisky and demanded that the Argentine government take action. In friendly terms the Argentine government agreed to change its stance and nullified the law in the year 1993.

In addition there are provisions in the Penal Code and the Civil Code as well as Supreme Court decisions that regulate the work of journalists and freedom of the press. The Penal Code has typified the crimes of "slander" ( calumnias ) and "insult" ( injurias ). In Article 109 it states, "Slander or false accusation of a crime that results in public action is punishable with a prison term of one to three years." Article 110 reads, "Anyone that dishonors or discredits another will be given a fine of between $1,000 and $100,000 Argentine pesos or jail term of one month to one year." When an individual feels that he has been a victim under these rules, he can file a suit. The effect of these articles extends to those who publish or reproduce these declarations made by others and to those who are considered as authors of the original statement. Articles 114 and 115 specify that editors in news organizations that publish such statements can be forced by the plaintiffs to publish the judicial sentence or extend some retribution for the offenses. And a safety valve was introduced in Article 117, which allows offenders to avoid penalties if they publicly retract before or at the same time they respond to the legal suit.

The articles in the Penal Code related to "slander" and "insult" have generated controversy with civil libertarians because such provisions have been used in many occasions to punish news organizations. As of 2002 the federal Congress is debating a bill that would restrict the extent of these articles by excluding those individuals who have become involved in issues of public interest (i.e., government officials) and by reducing or eliminating the liabilities of news organizations that publish such statements. In a publicized case, the news magazine Noticias was fined $60,000 dollars for having published reports of political favoritism involving President Menem and an alleged love affair.

The Civil Code also has provisions that protect an individual's honor. If someone is found guilty of "slander" or "insult," the court can establish an amount of money to be paid in compensation to the victim. As of the middle of 2002, there is a bill in the Senate that would modify Article 1089 of the Civil Code to limit its reach. The intended bill is similar to the project to reform the Penal Code, in that it excludes those individuals who have become involved in issues of public interest, and it eliminates the liabilities of news organizations that publish such statements.

The Supreme Court of Argentina ruled in 1996 in a legal case against journalist Joaquin Morales Sola over statements published in his book Asalto a la Ilusión that the person filing the suit needs to prove that the information contested is false and that the party publishing the statements knew they were untrue. This position, known as the doctrine of "real malice," is similar to the arguments advanced by the Supreme Court of the United States in the case of New York Times Co. v. Sullivan in 1964.

A few years before this case, the Argentine court had issued another ruling with important implications for the press. This is the case known as "Campillay," which started after three major newspapers published an article that attributed certain crimes to the recently detained Julio Campillay, an ex-police officer. The newspaper articles included an almost literal copy of the police reports without specifying the original source. The ruling against the newspapers established that to avoid litigation, press reports needed to specify the appropriate source, use a corrected verb tense to avoid imputing the crime to the alleged offenders, or leave the identity of those implicated in an illegal act unknown.

The press has also been affected by Supreme Court rulings and civil code regulations over the right to privacy. Article 1071 of the Civil Code protects the right to privacy, and allows judges to impose financial penalties and force public retractions to those found guilty of having violated another person's right to privacy. The most famous ruling on this matter came on December of 1984 in a case originated after the national magazine Gente published a front-page photo of Ricardo Balbin (ex-presidential candidate and leader of the political party UCR) dying in the intensive care unit of a hospital. The court found that because the picture had been taken without the permission of the family, and because it was not a public event, the magazine was in fault and had to pay compensation to the wife of Mr. Balbin.

Many press organizations have complained against recent Supreme Court decisions that they see as unconstitutional and contrary to international treaties, such as the "Pact of San José, Costa Rica," mentioned before. In one case the highest court found journalist Bernardo Neustad guilty for comments made on his television show Tiempo Nuevo by one of his guests, who implicated a local judge in controversial (i.e., illegal) activities. The journalist, the television channel, and the guest who made the comments were all fined heavily. In another case the Supreme Court refused an appeal by journalist Eduardo Kimel, who in 1999 was found guilty of insulting a former judge in his book La Masacre de San Pedro, which narrates the killing of five priests during the military government. The journalist was given a jail sentence in addition to a fine of $20,000 dollars.

Another legal provision that affects free speech is the "defense of crime speech" ( apologia del delito ). It is a judicial term for a free speech violation that involves the diffusion and promotion of crime. It is usually very difficult to prove, but it has been used against politicians, former military or police personnel, and others for comments usually reproduced in the media.

The courts have had mixed responses to the use of hidden cameras, a growing modality in investigative journalism for television. Sometimes the courts have used them as key evidence, but on other occasions they have not taken such filming into consideration. Many well-known television shows like Telenoche Investiga use hidden cameras, which have been very useful to uncover widespread evidence of corruption in many segments of public life. At the moment the country lacks regulations regarding the use of hidden cameras.

The labor law regulating working conditions for journalists is called the Estatuto del Periodista, and it was originally enacted in 1945. It has provisions for working hours, vacations, severance pay, and seniority, among other issues. The number of working hours established under this statute is 6 a day, with overtime pay equal to double the regular hourly rate. Vacation time starts at 20 days a year (5 more than most other workers) and increases with seniority. In regard to severance payments, journalists enjoy a special clause that provides them with a better compensation than most other workers, originally included to protect an allegedly unstable profession.

The actual implementation of this statute, among other things, has been severely undermined by the severe economic situation of the last few years. The only part that until recently had been regularly respected was the severance pay provision. Until recently journalists in Argentina were receiving a sum equal to 10 months of work plus an extra month for each year of work, but now even that seems to be disregarded. In a case involving the lack of enforcement of this provision, a judge sided with the firing of the journalist by the press company, which paid a severance amount equal to a typical worker. Forced reductions of salaries have also been challenged legally. So far, they have not been overturned.

In regard to a journalistic code of behavior or "Ethics Committee," Argentina lacks both. There is disagreement among the different actors in the press with regard to the establishment of a code of ethics for the profession. The Association of Press Entities of Argentina ( ADEPA ) has come out strongly against any such rule, which it sees as a violation of press freedom. However both major newspapers, Clarín and La Nación, have in place a code of ethics that apply to their writers and editors. Some of the main requirements imposed by it include:

- A clear differentiation between advertising sections and news sections to avoid misleading readers and suggestions of editorial endorsement.

- News articles should clearly differentiate between personal opinion and factual reporting, using editorial pages to present individual perspectives on issues.

- Journalists must avoid slander and insult, and must respect the privacy of individuals.

- Reports on crime should not assign culpability until after a judicial sentence on the case.

- Journalists are entitled to preserve the anonymity of their sources of information.

- Journalists cannot receive outside monetary compensation for publishing newspaper articles.

- According to the law, the name and photographs of minors involved in judicial proceedings cannot be published, nor can those of rape victims.

- It is forbidden to offend or insult people because of their race, religion, and color of their skin, or political ideas.

Censorship

The most dangerous time to be a journalist in Argentina was certainly under the military government that controlled the country between 1976 and 1983. According to the Buenos Aires Press Workers Union ( UTPBA ), during that period a total of 84 journalists were kidnapped and disappeared. The military rulers exercised explicit censorship in all of the media and pushed many press organizations to close. At least 10 national newspapers were shut down, and those that survived were subject to government controls. The military had a tight grip over all of the state media, including all national television channels. The media's inability to openly address the widespread human rights violations in the country and the disinformation spread during the military conflict with England in 1982 are two of the most grotesque cases of state censorship in this period.

The process of democratization initiated at the end of 1983 brought about a radical change in freedom of the press, including the dismantling of the state censorship apparatus and increasing access to government information.

Currently Argentina does not have governmental institutions dedicated to censoring press material before it is published. Nevertheless political pressures, by interest groups or government officials, have allegedly surfaced on occasion, such as in the control over state advertising funds, apparently helping to soften or to avoid certain news. Publications that include pornographic material are required to have a plastic cover with a warning sign prohibiting their sale to minors below the age of 18. The Federal Broadcasting Committee ( COMFER ) supervises and controls radio and television, including language and time of broadcasting, but it does not affect printed media like newspapers and magazines.

Argentina currently lacks any specific laws over journalist access to public government information. If a public agency were to refuse information to reporters, they could initiate a legal case, which would require proof of public interest in the information requested and of the arbitrary nature of the decision made by the public official. If a judge finds merit in the petition, a judicial order can force the agency to release the information. There are no laws limiting speech by government officials. There is currently a bill being debated that would expand on the issue of state information, including the forced declassification of government information after 10 years.

In regard to data about an individual that the state may have, the constitutional reform of 1994 introduced the right of habeas data. According to Article 43 of the Argentine Constitution, any individual can have access to information about himself that is in public registries or databases as well as in some private databases. In case of untruthfulness or discrimination, the individual affected can demand the nullification, correction, confidentiality, or actualization of such information. In addition, the state cannot alter the secrecy of confidential sources for journalists.

In the decades that followed the return of democracy, intimidations, threats, and violence diminished but did not go away completely. In many cases the local police or corrupt public officials were the alleged agents undertaking the repression of investigative journalists. The Buenos Aires Press Workers Union ( UTPBA ) reported 1,283 cases of violent aggression toward journalists between 1989 and 2001. The years with the highest number of reported abuses were 1993, with 218 cases and one murder, and 1997, with 162 cases and also one journalist killed.

Since 1993 newspapers have called attention to the murder of three journalists: Mario Bonino, José Luis Cabezas, and Ricardo Gangeme. The first victim in the 1990s was Mario Bonino, a journalist for the newspapers Sur and Diario Popular and a member of the press office of the UTPBA. He was found dead in the Riachuelo River four days after disappearing on his way to a seminar in November 1993. The judicial official in charge of the investigation found that the journalist had died under suspicious circumstances. According to Amnesty International, the death of Bonino occurred in the context of an increased campaign of threats and intimidation against journalists. Soon before his death, in the name of the UTPBA , he had denounced the death threats received by journalists in the province of San Luis. More recently, on April 19, 2001, the television show Puntodoc/2 presented footage where a former police officer from the province of Buenos Aires implicated other police agents in the killing of Bonino. The case remains open.

The brutal assassination of photojournalist José Luis Cabezas in January of 1997 is the most famous case of violence against the media in recent times. The 35-year-old magazine news photographer was found handcuffed and charred in a cellar near the beach resort of Pinamar. He had been shot twice in the head. A few days after his death, thousands of journalists, citizens, politicians, and members of human rights groups wore black ribbons while marching through the streets of Buenos Aires in silence as a sign of protest to the murder. As a journalist for the magazine Noticias, Cabezas had recently photographed reclusive Argentine businessman Alfredo Yabran, accused of having Mafia ties. Mr. Yabran committed suicide in May 1998, after a judge ordered his arrest in connection with the murder of Cabezas. In February of 2000, 8 out of 10 persons accused in this crime received sentences of life in prison. Three of those with life sentences were members of the Buenos Aires police department.

The more recent case involves the murder of Ricardo Gangeme, owner and director of the weekly El Informador Chubutense from the southern city of Trelew, on March 13, 1999. He received a gunshot as he arrived home. The journalist, who had previously worked as an editor at Radio Argentina and as a reporter for the Buenos Aires newspaper Crónica, was known for investigating corruption in government and business, and had reported threats to the police. Prior to his murder Gangeme wrote about irregularities in three legal suits involving the directors of the Trelew Electrical Cooperative. Six months after Gangeme's murder, the judicial official in charge of the investigation determined the arrest of six people allegedly involved in the killing. The arrested were associated with the administrative board running the city's electricity cooperative, which had been accused of corruption by Gangeme.

According to the Argentine Association for the Defense of Independent Journalism ( PERIODISTAS ):

…1997 was the year of the greatest regression in press freedom in Argentina since the restoration of democracy in 1983. If in previous years, repressive bills on press freedom and lawsuits against journalists presented by government officials threatened the consolidation of a right won with great difficulty, in 1997 the murder of photographer José Luis Cabezas, the proliferation of attacks, threats and insults against journalists, official treatment of the press as a political rival and the encouragement by President Carlos Menem to attack the press by saying that citizens had 'a right to give (the press) a beating': all helped put freedom of thought and expression in a serious predicament.

There are also several reports from PERIODISTAS and the UTPBA that in the last few years reporters have been physically attacked or seriously threatened by a variety of social actors such as police officers, union activists, politicians, agitators, party militants, public officials, and individuals associated with the prior military regime. In one case in the province of Santa Cruz, the radio station FM Inolvidable was attacked four times (including a firebomb) after reporting on the drug trafficking and car robberies in the port city of Caleta Oliva.

In addition there is the case of illegal spying on journalists by state agencies. One case that gained notoriety in recent years involved the illegal spying on reporters by the intelligence services. According to reports in Página 12 and Crónica, during 1999 the Air Force's intelligence services, concerned about investigations by journalists on the privatization of the country's airports, initiated an illegal inquiry that included spying on eight journalists from major newspapers. Following a judicial investigation, five members of the military were arrested and charged with plotting the illegal search.

State-Press Relations

The state had a dominant role over the media between the years of 1973 (when General Peron returned to power) and 1983 (when the military government fell, and elections were called). From 1973 to 1976 television was in the hands of the government, run during that time by the Peronist party ( Partido Justicialista ). The state took an aggressive stand to gain control of television, confiscating private channels and taking advantage of license expirations. The government also moved to organize a state media bureaucracy that had under its jurisdiction the news agency TELAM, National Radio and its 23 affiliates in the interior of the country, 36 other radio stations, the National Institute of Cinematography, the national television channel ( Canal 7 ), and four other television channels. Poor management and large financial losses characterized these agencies throughout this period.

The military government that took power in 1976 also extended its grip over state media, seeking to perpetuate the control they had already imposed in other areas of Argentine public life. Struggles within the different branches of the armed forces led to a division of control over media outlets. In this regard, the presidency exerted control over Channel 7, the army over Channel 9, the air force had Channel 11, and Channel 13 was shared among them. An important technical development during this period came in 1978, with the hosting of the soccer World Cup. The improvements made for the event included direct satellite communication with over 400 broadcasting units within the country and the move to color television, which formally started in May of 1980. Another related event during this period was the passage of a broadcasting bill, "Law 22,285" in 1980, which opened the door for the slow introduction of a private role in television and radio. In particular, the law sought to prevent businesses involved in printed journalism from expanding into broadcasting media and also to restrict the creation of national television networks. Under this law, one channel ( Canal 9 ) was privatized in October of 1982. The first private owner was Alejandro Romay and his company TELEARTE S.A.

The new democratic period began at the end of 1983 following the election of Raúl Alfonsin from the UCR party. During his government drastic changes occurred in the areas of freedom of the press and stopping the violent attacks of the preceding era. On the legal front the new democratic government did not alter the status quo, and no important media privatization projects were undertaken under this government.

The next president, the Peronist Carlos Menem, was elected in 1989 and again in 1995. He introduced major changes in the regulations of television and radio, privatizing several state television channels, permitting the creation of national networks and introducing greater foreign participation. While on the one hand Menem benefited private ownership of the press, on the other hand he had a very contentious relationship with journalists. Public encouragement by President Carlos Menem to attack the press by saying that citizens had 'a right to give (the press) a beating' is one example. According to the independent organization PERIODISTAS, by the end of 1997:

…The decision of a private TV channel to pull two of its shows because of pressure from the government created a new type of threat against freedom of expression: that of media owners who have other business interests. In the case of the programs Día D led by journalist Jorge Lanata, and Las patas de la mentira produced by Miguel Rodríguez Arias, the main shareholder of the América TV channel which aired the programs is also in one of the groups bidding in the privatization of 33 domestic airports. Information on the cancellation of the journalists' contracts was communicated by people close to government before it was announced by the channel authorities.

The media companies that had been part of the state for decades were reorganized by an executive decree in January of 2001. The government created a new multimedia state company, Sistema Nacional de Medios Públicos Sociedad del Estado, that merged with other smaller agencies. In the process it dissolved the state companies that ran the television channel ATC, the news agency Telam, and the Official Radio Broadcasting Service, whose functions are now part of the new state conglomerate. In 2002 another decree placed a government official to oversee the restructuring of this state company.

Accusations of political uses of advertising money by the state have surfaced in a number of occasions in the last few years. The agencies running the advertising decisions of the state have been political appointees (i.e., "partisan allies") of the administration in place. The board running the state multimedia company has ample powers to determine the allocation of advertising for every sector of the executive branch, including state-dependent companies. There is no auditing agency or independent control mechanism over decisions made regarding state advertising. Allegations of pressures to withdraw state (federal and provincial) publicity funds have grown, including some that eventually led to the filing of legal suits. The main victims have apparently been the poorer media organizations in the interior of the country that many times are heavily dependent on these funds to make a profit. Such allegations have surfaced in the provinces of San Luis, Mendoza, Chubut, La Rioja, Santa Cruz, and Rio Negro.

The relationship between governors and the media has been controversial in many provinces. In the province of Salta, the main newspaper El Tribuno is owned by the governor. This has led to questions about press independence in that area of the country. In the province of Santiago del Estero a serious dispute between journalists and provincial political party "machines" has grown in the last few years. A judicial ruling from an allegedly friendly provincial judge ruled against the newspaper El Liberal and ordered the payment of monetary compensation to the women's branch of the local Peronist party. This is the third such judicial ruling, which carried a penalty of $600,000 from 11 different criminal counts. According to Danilo Arbilla, president of the Inter-American Press Society (SIP), "we are surprised that public agencies from Santiago del Estero and from the federal government have not acted on this matter yet, given their knowledge that this is clearly a campaign directed by the provincial administration, which uses a judicial system of little independence, to punish a news media organization for criticizing the public administration and their political activities." The controversy started after El Liberal from Santiago del Estero reproduced reports, published in the newspaper La Voz del Interior from the neighboring province of Cordoba, that were critical to the women's branch of the dominant Peronist party run by the governor's wife. Since then, political groups allegedly connected to governor Carlos Juarez have responded with distribution and working barriers against both newspapers.

The relationship between legislators and the media turned sour in the year 2000 after newspapers reported on a bribe scandal in the Argentine Senate. This halted progress on an important bill protecting press freedom, which had been demanded by journalists for some time. A judge investigating the scandal said that it appeared that government officials bribed senators of the opposition Peronist party, as well as some of its own senators, to vote for a controversial labor reform bill. These allegations rocked the De La Rua administration, which had been elected with a mandate to fight corruption a year before. One of the 11 legislators called to answer questions before a judge was Senator Augusto Alasino, who was forced to give up his job as leader of the opposition Peronist Party in the upper house. In an apparent effort to get back at the press, Alasino later introduced a bill rejecting "the unlimited use of freedom of expression." The bill never passed.

As of mid-2002 the president of the country had a radio show on the public station Radio Nacional. The show, called Dialogando con el Presidente, was broadcast twice a week for two hours.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

Foreign correspondents need an accreditation provided by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. This credential, renewable every year, is issued by the ministry after a specific request by the media company hiring the journalist. The Association of Foreign Correspondents in Argentina has a special agreement with the government, and requests for such permits can be processed at its office instead of the government's agency. To be able to work inside governmental buildings such as the National Congress or the president's office and residence, a special accreditation provided by the respective institutions is required. According to this foreign press association, in Argentina there are around 150 foreign correspondents, half of which are Argentines working for foreign media companies.

The current government of Argentina does not review or censor cables or news sent abroad by foreign journalists working in the country. The last time some type of censorship mechanism was imposed was during the last military government (1976-83), when the state checked on foreign correspondents' activities as part of their overall objective of controlling the news flow. There are no established procedures for government relations with the foreign press. The holding of a special presidential press conference for the foreign media on a monthly occasion is now a not-so-regular event.

Foreign ownership of media companies started to increase with the withdrawal of state companies and the slow deregulation of the market that began after the election of Menem to the presidency. In 1989 the government dropped the 10-year residency requirement for receiving a broadcasting license. In regard to the newspaper business, companies from Spain have made important inroads in the market. The Spanish group Recoletos has recently acquired 100 percent of shares in the leading financial newspaper El Cronista and the magazines Apertura, Information Technology, and Target. The Spanish group Correo is a partner with the two leading Argentine newspapers in a company called CIMECO, which owns the regional newspapers La Voz del Interior and Los Andes, each one dominant in their local markets (83 percent and 73 percent of provincial circulation respectively).

An Argentine investor sold the first privatized television channel, Canal 9, to the Australian company Prime Television for $150 million in 1997. Two years later the Spanish company Telefonica bought it for $120 million. And in 2002 it was bought by an Argentine consortium. Another foreign player in broadcasting is the Mexican group CIE Rock & Pop, which currently owns eight radio stations.

In light of the serious financial situation faced by the local news media, Congress is discussing a law limiting the share of foreign companies in cultural enterprises. According to the new project, foreigners would have a 20 percent limit in the share of national media companies. The bill passed the Senate, but it still needs the approval of the lower chamber.

News Agencies

Argentina has three major news agencies, one of which belongs to the state. A board appointed by the government, which often seems to reflect political interest more than professional aptitude, controls the state agency Telam. Recently the state multimedia company that runs Telam has entered a major restructuring, and the future of the agency is uncertain. The other two big national agencies, DYN and Noticias Argentinas (NA), are run by major newspapers. The former is partly own by the two biggest newspapers Claín and La Nació, and the latter belongs to the group that controls Diario Popular. They are both national agencies that supply information to national and provincial media.

Two other smaller news agencies are the Agencia de Diarios Bonaerenses, based in the province of Buenos Aires, and the Agencia Informativa Católica Argentina, which is a Catholic Church agency focusing on news related to religious and church matters. There are also news agencies run by universities, such as the University of La Plata ( AIULA ) and the University of Lomas de Zamora( ANULZ ). These two agencies are run by journalism students and are self-financed with their revenues from selling information mainly to newspapers and local radios.

Major foreign news agencies with bureaus in Buenos Aires include: ANSA (Italy), Associated Press (United States), Bloomerang (United States), EFE (Spain), France Presse (France), Reuters (UK), United Press International (United States), and Xinhua (China). Some other foreign press news organizations in the country include: Deutsche Press (Germany), Europa Press, Bridge News (United States), BTA (Bulgaria), Milliyet (Turkey), Pravda (Slovakia), Vatican Information Service, Inter Press Service, Novosti (Russia), Agencia Latinoamericana de Informacion, Prensa Latina (Cuba), Zenit, and Duma (Bulgaria).

Broadcast Media

As of 2002 about 10 million Argentines own television sets. According to the World Bank, Argentina has the highest rates of cable television subscribers in Latin America, with 163 per 1,000 individuals in 1998. The country has 46 channels of open television: 2 belong to the state, 11 to provincial governments, 4 to national universities, and 29 are private channels. Only 7 cities have more than one local TV channel: Buenos Aires, Tucumán, Rosario, Mendoza, Cordoba, Bahia Blanca, and Mar del Plata. The city of Buenos Aires has 5 national channels of open broadcast TV. One of these, Canal 7, is the only state-owned channel that broadcasts all over the country. Provinces have at least 2 channels of open TV that rebroadcast programs from the national stations. In addition there are 4 national cable channels and over 100 other cable channels that rebroadcast national and foreign shows.

Argentina has approximately 260 AM radio stations and 300 FM stations. Of these, 32 are located in the city of Buenos Aires. The number of illegal radio stations has increased dramatically in the last 20 years. It is calculated that there are over 1,000 unlicensed radio stations. To counter the increasing number of clandestine radio stations, the government has recently extended a large number of licenses and has also begun a program to facilitate the legalization of existing stations. Argentina has approximately 650 radios per 1,000 individuals.

According to the main umbrella organization for private media businesses in Argentina, CEMCI ( Comision Empresaria de Medios de Comunicación Independientes ), radio and television generate employment for 35,000 people, offering one of the highest wage rates in the country.

In 1989, soon after President Menem came to power, he modified press law 22,285 first passed under the military government and began the deregulation of broadcasting media. After this four television channels that used to be state-owned were privatized. This was the first major privatization of television channels since 1982. In 1999 the government of Menem also introduced important changes to the legislation affecting broadcast media. Radio and television regulations were affected by an executive decree (1005/99), whose main provisions were: (1) to increase the number of licenses given per business nationwide from 4 to 24, and maintain the limit of 1 per district and type of service, (2) to allow the creation of national networks, (3) to permit the transfer of licenses, (4) to drop the 10-year residency requirement for receiving a license, and (5) to give television and radio stations benefits regarding their own publicity.

The subsequent government of De La Rua limited the total number of television licenses issued to 12 out of those 24. It intended to limit the possible reach of such a network to only half of the country, which has 24 provinces. In regard to radio station licenses, the government now increased the prior limits to 4 as long as it accounts for no more than 25 percent of the local offer. In order to have 2 radio stations belonging to the same group, a minimum of 8 radio stations have to be in place in that locality. In practice the transfer of licenses is complicated to track down, since limitations were dropped and in some cases licenses are requested after the transfer has been in effect.

The Federal Broadcasting Committee ( COMFER ) is the government agency in charge of regulating radio and television, including language and time of broadcasting. The COMFER issues licenses to broadcast within the available frequencies, regulates transfers of licenses, and determines their expiration. First established in 1972, it is the agency in charge of enforcing the broadcasting law 22,285/80, the regulating executive decree 286/81, and complementary laws across the nation. The COMFER has a Supervision Center in the city of Buenos Aires and 32 delegations across the country, as well as an Assessment Area. A main task is the control of broadcasting material that is considered to be harmful to children. The broadcasting law 22,285 determines the agency's reach into areas such as the content of the transmissions (section 14), the use of offensive language (section 15), audience protection (section 16), protection of minors (section 17), participation of minors (section 22), advertising (section 23), time limits for commercials (section 71), and free broadcasting (section 72). The executive decree 286/81 also regulates advertising (articles 4 and 5) and the broadcasting time for protection of minors (article 7) among other matters.

In the application of the law, the COMFER can issue sanctions (i.e., infraction fees) and control the revenues that would come in the application of the federal broadcasting law. In practice, if the agency finds a violation through one of its monitoring centers across the country, it needs to start a file recording the alleged infraction. If the problem refers to the content of a broadcasting show or commercial, it goes to the Assessment Area, where the file is analyzed according to regulations and if a breach is confirmed, it is forwarded to the Infractions Area of COMFER. If the file arose in respect to direct violations (films with inappropriate rating for the time of broadcasting, advertising on medicines, advertising overtime, transmission of gambling events, etc.), it is forwarded to a different unit ( Dirección de Fiscalización ), and if the breach is confirmed, it is also sent to the Infractions Area. This latter office is the one required to notify the individual with the license and to present the appropriate documentation of the case. The alleged offender can appeal to the Judicial Directorate of COMFER.

Until recently COMFER had been receiving close to $140 million from tax collections earmarked to them. According to regulations, 25 percent of what television provides has to be invested in cinematography, 8 percent of revenues go to support the National Institute of Theatre, and the rest goes to the National Treasury. The government financially supports national radio and public television from other tax resources.

Electronic News Media

According to official figures, Argentina has 7.5 million telephone lines and 4 million active cellular phones. In 1999 the number of Internet users was calculated to be 900,000, which is equivalent to 2.5 percent of the population. The proportion of Internet users in the population is similar to that found in Brazil and Mexico. According to the World Bank, Argentina has 28 Internet hosts per 10,000 individuals.

On the legal front, Internet press continues to be regulated in a similar fashion as the press in general. Regarding Internet privacy, the Argentine Federation of Press Workers ( FATPREN ) has opposed a bill being debated in Congress because of its position against a provision that would allow employers to check employees' e-mail messages.

All major media organizations have Internet Web sites. These press sites provide users with a variety of news, information, and entertainment. Several include up-to-the-moment news together with access to their editorials, archives, live radio, or television. Some of these sites include:

- Agencia Diarios y Noticias (DYN) ( http://www.dyn.com.ar/ )

- Ambito Financiero ( http://www.1.com.ar )

- Buenos Aires Herald ( http://www.buenosairesherald.com/ )

- Clarín ( http://www.clarin.com )

- Cuyo Noticias, from the provinces of Mendoza, San Juan, and San Luis ( http://www.cuyonoticias.com.ar/ )

- El Cronista ( http://www.cronista.com/ )

- El Día, from the city of La Plata ( http://www.eldia.com.ar/ )

- La Gaceta, from the province of Tucumán ( http://www.gacenet.com.ar )

- La Nación ( http://www.lanacion.com.ar/ )

- Olé, a sports news site ( http://www.ole.com.ar/ )

- Página 12 ( http://www.pagina12.com/ )

- Parlamentario.com , a site with legislative news ( http://www.parlamentario.com/ )

- Periodismo.com , which includes links to over 20 radio stations ( http://periodismo.com.ar/ )

- La Razón ( http://www.larazon.com.ar/ )

- Río Negro On Line ( http://www.rionegro.com.ar/ )

- TELAM, the state news agency ( http://www.telam.com.ar/ )

- TELEFE Canal de television ( http://www.telefe.com.ar/ )

- TN24horas.com , from Todo Noticias cable channel ( http://www.tn24horas.com/ )

- La Voz del Interior from the province of Cordoba ( http://www.lavozdelinterior.com.ar/ )

- El Zonda, from the province of San Juan ( http://www.diarioelzonda.com.ar/ )

Education & TRAINING

Educational institutions in Argentina offer undergraduate as well as graduate degrees in journalism and in communication studies. There are also several colleges that provide technical training for people interested in a career in journalism. Media companies have been recruiting students with journalism degrees, but it is not a common requirement for entering the profession. Generally speaking all educational entities provide students with training in writing for the press and speech for public broadcasting. In addition, classes also provide students with a more general education in the social sciences.

All major universities offer graduate degrees in journalism. In addition, since 1999, the two major newspapers

Some of the universities offering degrees in journalism include: Universidad de Buenos Aires; Universidad Abierta Interamericana; Universidad Argentina de la Empresa; Universidad Argentina John F. Kennedy; Universidad Catolica Argentina; Universidad de Belgrano; Universidad de Morón; Universidad de San Andrés; Universidad Nacional de La Matanza; Universidad Nacional de La Plata; Universidad Nacional de Luján; Universidad Nacional de Quilmes; Universidad Nacional de Lomas de Zamora; Universidad Austral; Universidad Nacional de Córdoba; Universidad Nacional de Tucumún; Universidad Catolica de Salta; Universidad Nacional de Rosario; Universidad Nacional de Entre Rios; Universidad Nacional de San Luis; and Universidad del Museo Social Argentino.

In addition there is a state-sponsored Institute of Higher Education in Broadcasting ( ISER ) founded in 1951 and run by the Federal Broadcasting Committee ( COMFER ). Based in the city of Buenos Aires, the institute has three radio studios (two FM), two television studios, editing rooms, and a computer lab.

Argentina has two major awards targeted to the press and show business. The Konex foundation, a nonprofit

A smaller yearly event in recognition of the press activities involves the "Santa Clara de Asís" awards, given by the League of Family Mothers. They are targeted to broadcasting shows that have excelled in the defense of family values, culture, and "healthy" recreation. Another award to radio and television shows includes those handed out by the "Broadcasting Group," which beginning in 2002 takes into consideration public votes in its selection of prizewinners.

The main umbrella organization for private media businesses in Argentina is the "Independent Media Business Committee" or CEMCI ( Comision Empresaria de Medios de Comunicación Independientes ). It brings together six other major organizations: the Association of Newspaper Editors from Buenos Aires, the Association of Magazine Publishers, the Association of Newspapers from the Interior, the Argentine Association of Broadcasting Stations, the Cable Television Association, and the Argentine Association of Private Radio Stations.

Some other press organizations in the country include:

- PERIODISTAS: Founded in 1995 by a group of renowned independent journalists, it is a nonprofit organization supported by membership contributions. The membership includes newspaper directors, editors in chief, writers, and broadcasting journalists. It has maintained an independent trajectory and cultivated a plurality of views that has made it the main independent organization of journalists defending freedom of the press.

- Buenos Aires Press Workers Union (UTPBA): This is a labor organization that represents journalists from the city of Buenos Aires. It performs union activities, such as collective bargaining, as well as defending the individual rights of press workers. The organization has a training and research center, a library, and runs the press workers' health fund. In the last years it has maintained a critical position against the government and defended legislative threats to the welfare of its workers.

- COMUNICADORES: This is a recently established organization of journalists active in labor and freedom of the press issues. The membership of this organization is mostly from journalists who do not occupy management, editorial, or other hierarchical positions in media organizations.

- Association of Foreign Correspondents in Argentina: The Association of Foreign Correspondents is located in the city of Buenos Aires. Its membership of 130 includes journalists from all foreign media companies working in Argentina. It provides an avenue for foreign correspondents to meet and exchange information as well as a voice in public issues related to freedom of the press. In addition it helps foreign correspondents with accreditation paperwork and sometimes offers educational courses.

- Association of Press Entities of Argentina (ADEPA): This organization brings together owners and upper management of media companies (i.e., television, radio, and newspapers). It lobbies on matters that affect the economic and legal status of media businesses as well as freedom of the press. It has recently emphasized its support for government deregulation of the media and its opposition to restrictive judicial rulings.

- Association of Photojournalists from Argentina (ARGA): The association has a membership that extends all over the country. It is concerned with legal issues affecting the profession as well as press freedom and militancy. The latter became salient after the murder of photojournalist José Luis Cabezas in 1997.

- The Argentine Federation of Press Workers (FATPREN): This is a national labor organization composed of over 40 individual unions.

Summary

The press in Argentina has undergone significant changes over the last three decades. After suffering under a repressive military regime for seven years, it emerged as one of the institutional building blocks of democracy. As the country struggles with the difficult task of building a free society, journalists have consistently put themselves at risk in order to bring news to Argentine homes. As a profession, journalism has grown stronger in both political and economic influence. Many individual journalists, also the victims of a depressing economic panorama, have excelled in their professional achievements, winning international awards and helping locally to uncover government fraud, mafia activities, and human rights violations.

Media companies have also grown economically stronger under favorable legislation. The move to a more business friendly set of regulations started under President Menem. These changes allowed for a growth in private ownership of media companies never seen before. Many critics have lamented the decreasing role of state intervention and have accused big media conglomerates of monopolizing the market. Unions and the left have also protested what they see as excessive political influence of big media conglomerates. Whatever advantages these companies accumulated during the last decade, now they are forced to confront the ills of heavy liabilities.

The difficult economic situation in Argentina in mid-2002 leads most analysts to conclude that the short-term prospects for the country are bleak. This will seriously affect the press, not only as it suffers from the general malaise, but also for the consequences of possible violent social conflict on press freedom. For small media companies and provincial newspapers the panorama appears to be even worse. On the legal front, the slow erosion of norms benefiting press workers and the constant use of presidential decrees to undertake major changes in media regulation have opened the door to policy volatility in the next few years.

The rapid growth of electronic media and instant access to information also pose new challenges to old fashioned newspapers that have to adapt to a rapidly changing professional environment. The accelerated growth of Internet sites and availability of broadcasting media online will probably continue to grow in the near future, despite economic hardships.

Overall the future of the press seems complex and uncertain. Many important legal and economic issues that affect the profession are now being debated in Congress. Under the currently difficult state of affairs, the role of the Argentine press has, if anything, grown even more important.

Significant Dates

- January 1997: Photojournalist José Luis Cabezas is murdered, resulting in a national outcry.

- 1997: Antitrust legislation is passed, limiting the growth of media conglomerates.

- March 1999: Murder of journalist Ricardo Gangeme in the southern city of Trelew.

- September 1999: Presidential decree modifying broadcasting laws and favoring greater concentration of media ownership.

- 2000: Following press reports over illegal activities, the Argentine Senate becomes embroiled in a bribery scandal.

- January 2001: Decree reorganizing all state media companies under one central unit

Bibliography

Alemán, Eduardo, Jose Guadalupe Ortega, and James Wilkie, eds. Statistical Abstract of Latin America. Volume 36. Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Publications, 2002.

Amado, Ana Maria. El ABC del Periodismo Sexista [The ABC of Sexist Journalism]. Buenos Aires: ILET, 1996.

Avellaneda, Andres. Censura en la Argentina [Censor-ship in Argentina]. Buenos Aires: Editorial CEAL, 1986.

Blaustein, Eduardo, and Martin Zubieta. Deciamos Ayer: La Prensa Argentina bajo el Proceso Militar [Yesterday We Said: The Argentine Press under the Military Government]. Buenos Aires: Editorial Colihue, 1998.

Casullo, Nicolas. Comunicación, la Democracia Difícil [Communication, the Difficult Democracy]. Buenos Aires: ILET, 1983.

Fernandez, Juan. Historia del Periodismo Argentino [History of Argentine Journalism]. Buenos Aires: Prelado Editores, 1943.

Fraga, Rosendo. Prensa y Analisis Políticos [Press and Political Analysis]. Buenos Aires: Centro Nueva Mayoría, 1990.

Galvan, Moreno. El Periodismo Argentino [Argentine Journalism]. Buenos Aires: Claridad, 1943.

Halperin, Jorge. La Entrevista Periodistica [The Press Interview]. Buenos Aires: Editorial Planeta, 1990.

La Nacion. Manual de Estilo y Ética periodistica [Manual of Style and Journalism Ethics]. Buenos Aires: Editorial Espasa, 1990.

Laiño, Felix. Secretos del Periodismo [Journalism Secrets]. Buenos Aires: PlusUltra, 1987.

Llano, Luis. La Aventura del Periodismo [The Adventure of Journalism]. Buenos Aires: Editorial Peña, 1978.

Mitre, Bartolomé. Sin Libertad de Prensa no hay Libertad [Without Press Freedom there is no Freedom]. Buenos Aires: Fundacion Banco Boston, 1990.

Moncalvillo, Mona. Entre lineas [Between Lines]. Buenos Aires: Editorial Planeta, 1993.

OAS, Secretariat for Legal Affairs. "Treaties." Available from http://www.oas.org .

Periodistas. "Report on Press Freedom." Available from http://www.asociacionperiodistas.org .

Ramos, Julio. El Periodismo Atrasado: La Tecnologia es Ráro los Medios de Prensa Lentos [Backward Journalism: Technology is Fast but the Media is Slow]. Buenos Aires: Fundacion GADA, 1995.

Rivera, Jorege, and Eduardo Romano. Claves del Periodismo Actual [Keys to Contemporary Journalism]. Editorial Tarso, 1987.

Salomone, Franco. Maten al Mensajero: Periodistas Asesinados en la Historia Argentina [Kill the Messenger: Journalists Murdered in Argentine History]. Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana, 1999.

Sidicaro, Ricardo. Las Ideas del Diario La Nación [The Ideas of the Newspaper La Nación]. Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana, 1993.

Sirven, Pablo. Quien Te Ha Visto y Quien Te Ve: Historia Informal de la Television en la Argentina [Informal History of Television in Argentina]. Buenos Aires: Editorial la Flor, 1988.

Sortino, Carlos. Leyes en la Prensa Argentina [Argentine Press Laws]. La Plata: Universidad de La Plata, 1990.

——. Dias de Radio: Historia de la Radio en la Argentina [Radio Days: History of Radio in Argentina]. Buenos Aires: Editorial Espasa, 1995.

Ulanovsky, Carlos. Paren las Rotativas: Historia de los Grandes Diarios, Revistas y Periodistas Argentinos [History of the Big Newspapers, Magazines and Journalists in Argentina]. Buenos Aires: Editorial Espasa, 1990.

Ulanovsky, Carlos, Silvia Itkin, and Pablo Sirven. Estamos en el Aire: Historia de la Television en la Argentina [History of Television in Argentina]. Buenos Aires: Editorial Planeta, 1993.

World Bank. World Development Indicators 2000. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank, 2000.

Eduardo Alemán

Martin Dinatale

Any help appreciated. Name of the writer/title of his book/title of his newspaper.

Thanks

BG

Thank you.