Austria

Basic Data

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Austria |

| Region (Map name): | Europe |

| Population: | 8,150,835 |

| Language(s): | German |

| Literacy rate: | 98.0% |

| Area: | 83,858 sq km |

| GDP: | 189,029 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Daily Newspapers: | 16 |

| Total Circulation: | 2,503,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 374 |

| Number of Nondaily Newspapers: | 120 |

| Newspaper Consumption (minutes per day): | 57 |

| As % of All Ad Expenditures: | 31.10 |

| Number of Television Stations: | 45 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 4,250,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 521.4 |

| Television Consumption (minutes per day): | 221 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 999,540 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 123.4 |

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 1,450,000 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 177.9 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 63 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 6,080,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 745.9 |

| Radio Consumption (minutes per day): | 61 |

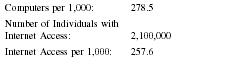

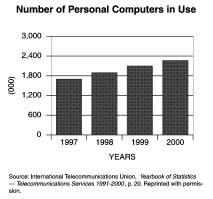

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 2,270,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 278.5 |

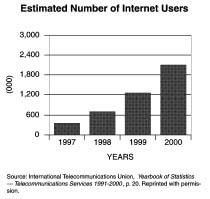

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 2,100,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 257.6 |

Background & General Characteristics

As of the early 2000s, Austria had a population of eight million people; nearly a fifth of its residents lived in the capital, Vienna. The population was ethnically, religiously, and linguistically homogenous, 78 percent Roman Catholic and 98 percent German-speaking. The country was divided into nine provinces. In the west the Vorarlberg borders Switzerland; Tyrol borders Germany and Italy. Carinthia borders Croatia and Slovenia to the south. Styria and Burgenland are bounded by Hungary and Slovakia in the east. Lower Austria (Niederösterreich, which surrounds Vienna) borders the Czech Republic, and Upper Austria (Oberösterreich) borders Germany to the north. The Salzburg province lay between Tyrol and the other provinces, sharing a short border with the German state of Bavaria. About 300,675 aliens also resided in Austria, around 60 percent of them workers (or their descendants) from the former Yugoslavia or Turkey who came during the post World War II reconstruction era. A small Slovenian minority lived in southern Carinthia, and groups of Croatians and Hungarians lived in Burgenland.

Public education began in 1774 and became compulsory in 1869. As of 2002, the literacy rate was 98 percent. A high standard of living and a long life expectancy (eighty-one years for women, and seventy-five for men) created a strong market for print media. Three-fourths of Austrians read a daily paper, spending a half-hour to do so, and three-quarters of an hour on weekends. On average Austrians watched about two-and-one-half hours of television per day, considerably less than in the United States. Surprisingly high numbers of young Austrians read newspapers: 68.6 percent of those between the ages of 14 and 19, and 72.6 percent of young people between 20 and 24. The better educated and self employed are more likely to read newspapers (80-85 percent of them do so) than unskilled workers or those who lack secondary education, about two-thirds of whom read a daily paper. Beginning in 1995 a private association, Zeitung in der Schule (Newspapers in the Schools) encouraged mainstream readership by providing free subscriptions and instructional materials for school classes, serving 60,500 pupils in 2000-01.

The first printing press arrived in Vienna in 1483, spurring development of early newssheets and broadsides. Der postalische Mercurius , a twice-weekly paper which first appeared in 1703, soon became an official organ of government, and its descendant, the latter-day Wiener Zeitung , could thus claim to be the oldest daily newspaper continuing as of 2002 in existence.

The democratic revolution of 1848 sparked an explosion of newspapers; about 90 dailies soon appeared in Vienna. Die Presse , also later titled Die neue freie Presse , was founded in 1848 and survived the political repression which followed the unsuccessful revolution. Karl Marx contributed articles as the paper's London correspondent between 1861 and 1862. Censorship of the press was officially abolished in 1862, although true freedom of the press could not be warranted until nearly a century later. The paper attracted a liberal middle class audience, especially assimilated Jews who opposed the clerical, conservative press. The Zionist Theodor Herzl served as Paris correspondent and literary critic for Die Presse from 1891 to 1904. Suppressed by the Nazis in 1938, the paper continued as of 2002 as the oldest of the country's general-purpose quality newspapers, defining itself as conservative and politically independent.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, compulsory education, the resulting increase in literacy, coupled with industrialization, urbanization, and the rise of the social democratic movement created an increasing demand for newspapers. In 1889 the Socialist Party founded the Arbeiter Zeitung , whose circulation reached 100,000 in the 1920s. During the 1930s a much smaller version was printed in Czechoslovakia and smuggled into Austria. Sensational tabloids sprang up in the late 1800s, among them the Illustrierte Kronen Zeitung , Austria's largest daily paper as of 2002.

The Hapsburg monarchy ruled Austria from 1273 until the end of the World War I. The Austro-Hungarian Empire governed Hungary, parts of Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Romania, Italy, and much of the territory that in the early 2000s was called Slovenia, Croatia, Yugoslavia, and Bosnia-Herzegovina. Vienna, a capital city designed for an empire of 50 million, presided in 2002 over a federal republic of some eight million Austrians. The city boasted a long and prestigious tradition of theater, opera, and music. In the early 2000s, it was the nation's press capital as well, home of the largest newspapers, the national press agency, the journalists union, and press club.

Austria's modern press began to develop rapidly after World War I in the transition from the Hapsburg monarchy to a federal democracy. The lifting of a ban on street sales of newspapers in 1922 stimulated the rise of a tabloid press, and within a few years Austrian newspapers were circulating 1.5 million copies, of which 1.2 million were in Vienna. The Nazi takeover in 1938, however, suppressed political expression. Before that, Die Presse had been forced to cease publication because several of its editors were Jewish. The Wiener Neueste Nachrichten became the leading Nazi organ. Of the 22 dailies in Vienna at the time of the Anschluss , only four remained in operation at the end of World War II.

The victorious Allies divided Austria and its capital into four zones of occupation; the country did not regain full independence until 1955. The Allies set up newspapers in their zones of occupation, first the Soviets' Österreichische Zeitung , which appeared in April 1945. The American occupying powers established Salzburger Nachrichten and Oberösterreichische Nachrichten in their zone, and the French and Americans supported the Tiroler Tageszeitung . These three papers were soon transferred to Austrian ownership. The postwar period also saw the appearance of the Kleine Zeitung , re-founded in Styria and Carinthia by the Catholic Press Association. Kurier , launched by the Americans, was bought by an Austrian industrialist in 1954; for decades it was the country's second largest newspaper with a circulation of nearly a half million. With the exception of the Soviets' Österreichische Zeitung , all of these dailies continued to occupy a strong position in Austria in the early 2000s. The socialist daily Express was taken over by Kronen Zeitung in 1975, making that center-left newspaper larger than its rival, the right-wing Kurier . The small tabloid Wiener Zeitung , with a circulation around 30,000 in the 1970s, held exclusive rights to publish government notices and advertising until 1996.

Die Presse was re-founded in 1946 as a weekly paper in Vienna, and then in 1948 it resumed daily publication. The Federal Chamber of Commerce owned an 80 percent share in Die Presse , whose independence and journalistic freedom were nonetheless guaranteed. In 1985 it became the first European newspaper to install an electronic editing system, and in 1993 the paper introduced color photos and graphics. The Federal Chamber of Commerce withdrew from ownership in 1991, and Styria Verlag, publisher of the Kleine Zeitung , took over Die Presse . Two years later it adopted a smaller format, necessitated by print machinery, and the need to compete for kiosk display space with the smaller Standard , founded in 1988 as the youngest of the country's dailies continuing in existence as of 2002. In September 1996 Die Presse went online and rapidly gained readers, claiming 316,000 in 1997. Its liberal opposition stance meant boycotting the nationwide spelling reform in 1997 and publishing prices in Euros as well as Austrian schillings before the Euro replaced national currencies in 2002.

Political party ownership of newspapers appeared to be a safeguard against the type of censorship and propaganda which had existed under the Nazis, but the role of parties in the press declined throughout the second half of the twentieth century. The postwar period witnessed the appearance of Neues Österreich , published by the fledgling provisional Austrian government and its newly established political parties: the Christian Democrats, Socialists, and Communists. The conservative Austrian People's Party founded the Kleines Volksblatt (which ceased in 1970); the Socialists resumed publication of the Arbeiter Zeitung , and the Communists created the Volksstimme. Neue Zeit also began as a weekly owned by the Socialist Party in 1945 and was purchased by its employees in 1987. It had 16,000 subscribers and an estimated 80,000 readers in the late 1990s. Yet even a $2 million press subsidy from the federal government in 2000 did not suffice to prevent bankruptcy, and the paper ceased publication in 2001. The Socialists' Arbeiter Zeitung , begun in 1889, followed a similar path to independence as a left liberal paper in 1989 and was renamed Neue Arbeiter Zeitung , only to close for good two years later. The Austrian People's Party's (ÖVP) Neue Volkszeitung was sold to a private corporation in 1989, with the ÖVP retaining just a 10 percent share. In 1953 newspapers owned by political parties accounted for half of all circulation, while in 2002 for only 2.2 percent or 62,000 copies combined. Those papers remaining in party ownership were the two owned by the Austrian People's Party, Neues Volksblatt and Salzburger Volkszeitung , and the Socialists' Neue Kärntner Tageszeitung , which was managed and distributed by the largest Austrian media conglomerate, Mediaprint, from 1990 into the early 2000s.

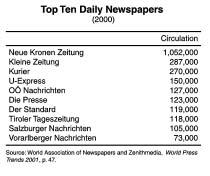

Given its high concentration of population, Vienna is also Austria's press and media capital, with five daily general-purpose newspapers: Neue Kronen Zeitung , Kurier, Die PresseDer StandardWiener Zeitung and the financial daily, Wirtschaftsblatt . Krone , (the newspaper's abbreviated title) published regional editions in Salzburg, Styria (Graz), Tyrol (Innsbruck), Oberösterreich (Linz), and Carinthia (Klagenfurt). Kurier published regional editions in Graz, Innsbruck, Linz, and Salzburg. Other cities large enough to have their own daily newspapers were (in order of size) Graz ( Kleine Zeitung ), Salzburg ( Salzburger Nachrichten ), Linz (Oberösterreichische Nachrichten), and Bregenz ( Vorarlberger Nachrichten and Neue Vorarlberger Tageszeitung ). Salzburger Nachrichten was the only national newspaper not headquartered in Vienna. Two federal states, Niederösterreich and Burgenland, depended on neighboring Vienna for their news and had no dailies of their own, although a short-lived daily, Guten Tag Niederösterreich , was launched in 1990.

By far the largest Austrian newspaper is Vienna's tabloid Neue Kronen Zeitung , also the most widely circulated Austrian newspaper abroad. It was published daily

Neue Kronen Zeitung 's leadership in circulation and advertising revenues was occasionally challenged between 1985 and 2000. In April 1988 Oscar Bronner of Berlin's Springer publishing house, launched a new liberal daily, Der Standard , the first new daily in previous 16 years. Der Standard was a quality paper of standard format with a distinctive salmon-pink color, rivaling Die Presse . It appealed to a younger audience, claiming that 57 percent of its readers were under 40. It offered broad coverage of international news, economics, politics, culture, and a substantial editorial section on its last page. In 1992 a former owner of Krone , Kurt Falk, launched Täglich Alles , printed in four-color intaglio. sold for three schillings at first, about a third the price of other tabloids, but it doubled in price five years later. It fought to gain readership by distributing free copies and offering games and prizes. It featured sensational headlines, a large television section, and took a strong stance opposing the European Union. A year after its start-up, it boasted 1.1 million readers, but soon it lost advertising revenue because of its sensationalism and political stance. It reached second place with 423,000 daily copies sold in 1998 but lost money and closed for good in August 2000, though it continued to appear online. In April 2001 Neue Zeit , with a subscription list of 26,000 and some 80,000 estimated readers, declared bankruptcy and folded. Kleine Zeitung gained the most in circulation with the demise of Neue Zeit and Täglich Alles .

Another new daily, Wirtschaftsblat , began publication in 1995 with an initial print run of 58,000, intending to compete with Der Standard . It was financed by an Austrian syndicate and the Swedish publishing group Bonnier and distributed by Mediaprint. It published financial and economic news Tuesdays through Saturdays and was available only by subscription.

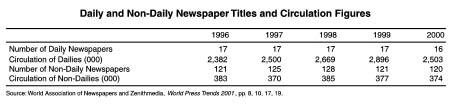

Through the 1980s and 1990s, the media scene in Austria was characterized by shrinkage in the number of daily newspapers and increasingly overlapping ownership, with several major papers owned partially by foreign firms. In 1998 Austria had 17 dailies, or 28 titles (accounting for regional editions), with a total circulation estimated at 2.9 million. In 2002 Austria was home to 15 daily newspapers, a small number in relation to its population. Switzerland, with a slightly smaller population of 7,283,000 has 88, and Germany, whose population is 10 times the size of Austria's, has 375 daily papers. Even after Austria's entry into the European Union in 1995, foreign newspapers failed to gain a readership in Austria, despite the common language the country shares with Germany. Three-fourths of those who read a daily newspaper choose an Austrian publication.

Media development in the postwar age was characterized by a lack of political opposition, with overlapping membership in the political establishment, government, and big business. Not until the late 1970s did Austrian newspapers begin to investigate, question, and oppose government policies, such as those surrounding nuclear power and ecological issues. The Chernobyl catastrophe of 1986 and the resulting popular rejection of nuclear power in Austria resulted in increased environmental coverage and greater questioning of government decisions, a process strengthened by the formation of Austria's Green Party in the 1980s.

News weeklies

In the early 2000s, among Austria's 40-odd news weeklies were several regional newspapers with local news for rural areas less well served by the large national dailies. The two newspaper-format weeklies were Niederösterreichische Nachrichten , whose 27 local editions reach 10.7 percent of the weekly news market in Lower Austria, and Oberösterreichische Rundschau with 11 percent of the market in Upper Austria. Lower Austria (Niederösterreich), which surrounds Vienna, had no regional daily to compete with the larger city papers. Many other weeklies were political party organs, or published by the Catholic Church.

One special niche filled by weekly papers was to serve minority groups which spoke languages other than German. Klagenfurt in Carinthia was home to three Slovenian language weeklies, Nedelja , Slovenski Vestnik , and Nas Tednik . A Croatian language weekly, Hrvatske Novine, was published in Eisenstadt in Burgenland. These papers might receive special press subsidies or be partially supported by the Catholic Church.

Austria's weekly news magazines reflected the same pattern of consolidation under overlapping ownership as the country's dailies. Profil and Trend , founded in 1970, were the first Austrian news magazines to outsell such German publications as Der Spiegel . Kurt Falk, half owner of Krone , launched Die ganze Woche in 1985 and sold it in 2001 to a company owned by his sons. With a press run of 700,000 and a reach of 37 percent, it became the third largest mass-media organ in the country, after Krone and ORF, Austria's public radio monopoly. In the mid 1990s Wochenpresse , which reported weekly on economic news, ceased publication, and Profil moved further to the left along the political spectrum

Brothers Wolfgang and Helmut Fellner introduced News , then TV-Media and, around 1997, Format , which reported every Monday on news, politics, economics, and science. Three-fourths of Fellner publishing was then sold to Bertelsmann, (Germany's largest book publisher) with a 30 percent share in News then owned by Media-print (WAZ). News reached 19.3 percent of the market in 2000, Format 7.1 percent, and Profil another 9.4 percent. The rival weekly, Trend , reported on economics and sold about 64,209 copies weekly, with a market reach of 8.1 percent. In early 2001 News and Trend /Profil merged, giving Bertelsmann and WAZ control over 59 percent of the Austrian news weekly market.

Economic Framework

Austria enjoyed economic stability and increasing prosperity after 1945. The most significant recent economic and political developments resulted from Austria's

The three largest newspapers, Neue Kronen Zeitung , Kurier , and Kleine Zeitung and Oberösterreichische Nachrichten were all tabloids, measuring approximately 9 by 12 inches and costing 9 or 10 schillings (US$.70 to US$.80). The quality papers read by the better educated and more affluent ( Die Presse , Der Standard , and Salzburger Nachrichten) were about equal in size of reader-ship and larger in format: about 12 by 18 inches. Die Presse cost the same price as the tabloids, while Salzburger Nachrichten and Der Standard cost about US$1.00 per issue. These three papers were distributed nationally by subscription, with a combined circulation of 321,000, or about 11.3 percent of the total national circulation of daily newspapers. Kleine Zeitung also touted that 93 percent of its copies were sold by subscription. The average monthly subscription in 2000 for six days of postal delivery cost around US$17.50, but the quality papers Die Presse and Der Standard cost about US$26 per month. Newspapers might be purchased as single copies at state-controlled tobacco shops or kiosks or subscribers might pick up their copies there, an arrangement that cost less than home delivery. The financial daily, Wirtschaftsblatt , which cost about US$1.50 per issue, was the most expensive of all.

Neue Kronen Zeitung , Kurier , and Kleine Zeitung dominated Sunday sales, since regional dailies and Presse and Standard did not publish on Sundays. The Wiener Zeitung did not publish Saturdays or Sundays and was available by subscription only. Many papers charged higher daily prices Wednesday through Saturday or on weekends.

Austria's Österreichische Auflagen Kontrolle (Circulation Control, ÖAK,) was founded in 1994 to verify circulation counts for advertisers. In 2000 the ÖAK revised the way newspaper circulation was calculated and the Neue Kronen Zeitung and Kurier participated in the count for the first time. According to the revised definition, papers were evaluated by the number sold on week-days during the third quarter of 2000. The findings indicated that Neue Kronen Zeitung sold the most with 874,442 copies reflecting 43.4 percent of the market.

In the mid-range of distribution was Die Presse (76,216 copies, 5.4 percent). The smallest distribution registered was for Neue Vorarlberger Tageszeitung (7,426 copies, 0.8 percent) ( VÖZ-Jahrbuch Presse 2001—Dokumentationen, Analysen, Fakten , November 2001). Two small papers, whose circulation was estimated at 20,000-25,000, did not participate in the official circulation count: Neue Kärntner Tageszeitung (Klagenfurt) with a reach of 1.2 percent, and Neues Volksblatt (Linz).

Sources estimated that the Neue Vorarlberger Tageszeitung sold fewer than 10,000 copies. In the 10,000 to 25,000 circulation range there were two papers: Salzburger Volkszeitung and the Wiener Zeitung , which specialized for decades in government announcements and advertising. Wirtschaftsblatt , financial information from the Viennese stock exchange, was the only daily in the 25,000 to 50,000 bracket. Five newspapers sold between 50,000 and 100,000 copies: the two large format Viennese quality papers Der Standard and Die Presse , and Tiroler Tageszeitung , Salzburger Nachrichten , and Vorarlberger Nachrichten . Some 100 to 500 copies were sold daily by the Oberösterreichische Nachrichten , Kurier, and Kleine Zeitung . Only the Neue Kronen Zeitung sold over 500 copies per day.

The economic framework of Austrian newspaper publishing in 2002 had been shaped by a series of mergers and the advent of foreign media conglomerates during the 1980s and 1990s. Germany's Westdeutsche allgemeine Zeitung publishing group (WAZ) entered the Austrian market in November 1987, purchasing 45 percent of Kronen Zeitung and increased its share to 50 percent in 1993. With a print run of nearly 2 million per day and a 43 percent share of the market, Krone dominated thescene. Westdeutsche allgemeine Zeitung purchased 45 percent of Krone 's closest rival, Kurier , in 1988 and increased its share to 49 percent in 1993. By 1992 Krone and Kurier were also publishing regional editions for the provinces. Austrian media analysts referred to this concentration of media power in German hands as KroKu-WAZ, an acronym blending Krone , Kurier , and Westdeutsche allgemeine Zeitung . In 1988 WAZ founded a company called Mediaprint, which managed and distributed these two major dailies, as well as the Socialists' smaller Kärntner Tageszeitung . The group bought a 74 percent share in the Viennese publisher Vorwärts , where the heavily indebted Arbeiter Zeitung was printed. That old Socialist daily was forced to cease in 1991. In 2002 Mediaprint employed a workforce of 3,500, and its papers reached over half of all Austrian newspaper readers.

Another major German player in the Austrian media market was Oscar Bronner, of Germany's Springer publishing group. In the 1960s he launched two weekly magazines, Profil and Trend . In 1988 he initiated the Standard , in which Germany's Süddeutsche Zeitung also owned a share. That paper originally reported on political and business news on days when the Viennese stock exchange was open, but soon it expanded to cover culture and sports as well. In 1989 the Springer Company bought a half share in the Tiroler Tageszeitung . Mediaprint (WAZ) launched a price war against Tiroler Tageszeitung in 1999, reducing subscription prices to its papers Krone and Kurier in Tyrol by nearly one half, to just $13 per month. At the same time, Mediaprint raised its prices in Vienna, Niederösterreich, and Burgenland by 7.2 percent. The Tiroler Tageszeitung complained to the courts, which ordered Mediaprint to cease taking advantage of its dominant market position.

These media conglomerates competed in distribution as well as advertising and subscription sales. In the mid 1990s the left-liberal Standard sued Mediaprint for refusing to distribute its paper, while still distributing other newspapers not owned by Mediaprint ( Wirtschaftsblatt ), but Standard lost the suit. In addition to the very common distribution via subscription or kiosk sales, the Neue Kronen Zeitung and Kurier sold papers by hawking them on the streets, in cafes, and in traffic during rush hours.

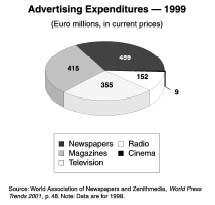

Daily newspapers attracted about 30 percent of all the money spent on advertising in Austria, with another 23 percent going to television and 8 percent to radio. Weeklies and other magazines accounted for an additional 23 percent of money spent on advertising. In the 1990s revenues from advertising accounted for over half the revenues of newspaper publishers, becoming more lucrative than newspaper sales. At the same time, papers needed to continue to attract a readership interested in and capable of purchasing the products advertised. Thus the better-educated, more affluent consumer was the newspaper publisher's target audience. In 2000 Austrian advertisers spent $2.24 billion, of which $1.257 billion, or 54 percent, went to print media. Fifty-two per cent of print advertising went to daily newspapers, and 48 percent to magazines.

Like newspaper sales, advertising revenues were concentrated at the top of the circulation pyramid, with Mediaprint's Kronen Zeitung and Kurier attracting about two thirds of all advertising revenues, leaving a much smaller share for lesser competitors. Regional papers struggled to support themselves through small classified ads, regional advertising, and sales. Through the 1980s newspapers lost advertising revenue to television and radio, where advertising on Sundays and holidays became legal. In 2002 the Mediaprint papers and large regional dailies Kleine Zeitung , Oberösterreichische Nachrichten, Salzburger NachrichtenTiroler Tageszeitung, and Vorarlberger Nachrichten , all turned a profit.

Until 2002, newspapers received preferential postal rates, which accounted for only 17 percent of the true cost of mailing publications; however, this cost affected more weeklies than daily newspapers, which were often bought at kiosks or tobacco shops. Regional newspapers in rural areas were most dependent on the postal delivery system. Despite objections by the Association of Austrian Newspapers, postal rates were raised in two stages, effective January 1, 2002 and January 1, 2003. When the transition was to be complete, rates for mailings up to sixty grams would have risen 282 percent over 2001, and rates for mailings heavier than 100 grams would have risen 157 percent. Saturday postage rates would have increased at an even higher rate. In 2001 the former rivals Standard and Presse began a common home delivery system to residents of Vienna, Niederösterreich, and northern Burgenland. However, home delivery by the publisher was the most expensive method of distribution.

In 1985 Die Presse was the first Austrian paper to use an all-electronic editing format. Der Standard made the leap to on-line publishing in February 1995, followed in September by Vorarlberger Nachrichten . That paper began four-color printing in 1994, and Täglich Alles began printing in four-color intaglio in 1992. In 1995 the Tiroler Tageszeitung opened a modern four-color printing plant as well. By 2002, four-color offset printing was the industry standard.

Mediaprint, as the country's largest newspaper publisher, also had the newest printing facilities. In 1989 it purchased 35 percent of one of Austria's largest offset printing firms, Tusch Druck. Its new printing plant in St. Addrä/Lavanttal opened in summer 2002 and employed 180 workers. It printed a total of 300,000 copies of its two major dailies, Krone and Kurier , and the entire print run of the Kärntner Tageszeitung.

The two largest suppliers of newsprint were Steyrermühl (in 2002 part of UPM Kymmene), and Bruck/Norske Skog, part of a Norwegian paper producer, the second largest in Europe. Norske Skog, located in Graz, produced 120,000 metric tons of newsprint a year, while Steyrermühl, located in the town of the same name in Upper Austria, produced 480,000 metric tons of news-print and uncoated magazine paper. Each year a group within the Association of Austrian Newspapers would negotiate a general agreement with these two producers, and then individual publishers would negotiate the details. There was no shortage of newsprint in Austria, but price increases in the double digits appeared in 2001. About three-fourths of the paper and cardboard produced in Austria was exported.

Press Laws

The Austrian constitution guarantees freedom of the press, and there is no state censorship of the media. A Media Act of 198l guaranteed objective and impartial reporting, ensured the independence of journalists and broadcasters, and required all media to disclose their ownership. The Media Act also protected individuals from invasion of their privacy, slander, libel, and defamation of character. Anyone who believed these guarantees have been violated had recourse to the Austrian Press Council, an independent watchdog agency founded in 1961 by the Association of Austrian Newspapers and the Austrian Journalists Union. The Austrian Press Council also represented interests of the press, radio, and television in negotiations with government agencies. The Media Act was amended in 1993 to require media to present opposing viewpoints and to offer citizens the right of rebuttal.

In the early 2000s, all newspapers, regardless of size, ownership, or general financial condition, received a general press subsidy, under an arrangement which originated in the mid 1970s. Beginning in 1973, Austrian newspapers were subject to a value added tax at a reduced rate of 10 percent. After complaints by the newspaper editors and publishers association, state subsidies for newspapers and magazines were introduced in 1975 in order to ensure the survival of a broad spectrum of public opinion. While the existence of such government subsidies might reduce press criticism of the state, a governing committee of representatives of the chancellor's office, the journalists' trade union, and the Association of Austrian Newspapers ensured that such pressure did not apply. In 2001 the country spent about $64 million on general newspaper subsidies awarded to the 16 dailies then in existence. Larger newspapers received more funding, so the subsidy did not effectively promote the publication of smaller papers or a broader range of viewpoints. Effective in the early 2000s, Austria could not refuse the general press subsidy to newspapers dominated by foreign ownership because doing so is prohibited by the European Union.

A Press Promotion Law of 1985 defined recipients of a second, special press subsidy (amounting to more than the general subsidy) as "daily newspapers of particular importance for the formation of public opinion which do not have any dominant market position." To qualify for special press subsidies, a paper had to reach between 1 percent and 15 percent of the population of its province, or a maximum of 5 percent nationwide. Advertising must not amount to more than 22 percent of total pages. In 1993 the press subsidy system was revised and new regulations were put into place to control future mergers in the media industry. In 2001 six papers received special subsidies totaling $80 million, excluding Neue Zeit , which closed, despite having received a special subsidy of $2 million the previous year. The Standard and Salzburger Nachrichten were denied subsidies for exceeding the limit on the proportion of space that could be devoted to advertising three times within the previous five years. The special subsidies awarded amounted to $2.8 for Die Presse , $1.5 million for the Kärntner Tageszeitung , around one million apiece for the Neues Volksblatt and the Neue Vorarlberger Tageszeitung, and slightly under one million for the Wirtschafts blatt. Beginning in 1979 subsidies were also awarded for the education and training of journalists, to a total of nearly three-quarters of a million dollars in 1997. Since 1983 further subsidies supported the modernization or construction of new printing plants. Provinces may also subsidize newspapers, in some cases through direct investment, elsewhere through measures such as tax breaks for new printing plants.

Austria did not enact major anti-trust legislation until 1993, believing that media consolidation strengthened the country's position against outside competition. But the large role played by Westdeutsche allgemeine Zeitung and other foreign owners stimulated a change of philosophy. Those media conglomerates already in existence, however, such as Mediaprint, were not obliged to diversify. Wiener Zeitung lost its monopoly on federal government announcements and advertising in 1996 because the monopoly violated regulations of the European Union, which Austria had joined a year earlier. Formerly owned by a department of Austria's State Printers, it became independent in 1997.

In January 2001 a legal decision based on Austrian cartel law defined the media market in such a way as to find no violation in the concentration of ownership in weekly news publications. Yet discussions about the necessity of examining the joint impact of print, radio, and television and of reforming cartel law and breaking up existing conglomerates rather than merely forbidding new mergers have surfaced in the Austrian media.

The Association of Austrian Newspapers (which in 2002 maintained a Web site at www.voez.at ) often lobbied the federal government on matters affecting the media. In 2001 the organization urged repeal of a law requiring that advertisements to be subject to a special tax, which could range as high as 30 percent. Austrian firms could advertise their products and services in foreign media without paying the special tax. This policy, unique to Austria, placed the country at a disadvantage in attracting advertising in the international market.

Austria also regulated the content and nature of advertising, which had to be identified as such, not masked as advice or commentary. Advertisers had to be able to prove the truth of statements made about their products. Newspapers could refuse to publish certain advertisements or newspaper inserts without stating any cause. Austrian law prohibited advertising directed at children from attempting to persuade them that the possession or enjoyment of certain products is a goal in and of itself and warned that parents should not be portrayed as negligent nor children as inferior if they do not own or buy certain products. Violence in advertising was forbidden. The dignity of women should be respected in advertising, and women should not be portrayed as incompetent in using technology or driving, for example, or shown predominantly as housewives or lower-ranking employees.

Censorship

Austria had several federal laws which guaranteed freedom of expression and prohibited censorship, particularly a 1981 federal law on the press and other journalistic media. This law required all media to disclose their ownership and stipulated that confiscation or withdrawal from publication could occur only after a court order. Broadcasting must be objective and must represent a diversity of opinion. Private citizens were protected from libel, slander, defamation, or ridicule in the media.

All major media groups subscribed to Ehrenkodex für die österreichische Presse (the code of ethics of the Austrian press). It stated that readers must be able to differentiate between factual reporting and editorial commentary. Journalists should not be subject to external influences, whether personal or financial. The economic interests of the publisher should not influence content to the point of falsifying or suppressing information. Racial or religious discrimination was not permissible, nor was the denigration or mockery of any religious teaching by recognized churches or religious communities. The intimate sphere of public figures had to be respected, especially where children were concerned. Protection of the individual's rights must be carefully weighed against public interest, which might mean exposure of serious crimes or risks to public security or public health. Photographs of the intimate sphere of public figures could only be published if the public interest outweighed voyeurism. Retouched photographs or photo montages should be identified as such. Travel and tourism reports should mention the social and political background of the region, for example serious human rights violations. Reporting on automobiles should contain energy consumption and environmental information. Moreover, courtroom television, live radio broadcasts, and photography of court proceedings were prohibited. Journalists who quoted pre-trial court proceedings could be punished with up to six months in prison.

Violations of this code of ethics were brought before the Austrian Press Council for deliberation. It represented the press within federal government bodies, ensured press freedom, and watched over citizen complaints. While the Press Council lacked legal means to enforce its decisions, it was generally respected by over 100 print media who subscribed to its code of ethics. In 2001 the Austrian Press Council debated 35 violations of the code of ethics, many concerned with the publication of sensational or gruesome photographs. Other cases concerned failure to disclose conflicting financial interests, inappropriate portrayal of public figures, and unfair coverage of a political party. The Council's sanctions were limited to requiring offenders to publish apologies or rebuttals; it had no authority to impose legal penalties or financial settlements. Its jurisdiction was limited to the content of print media and excluded their business dealings such as attempts to recruit readers. Furthermore, it had no authority over online publications.

State-Press Relations

After World War II, Austrian media policy aimed to establish strong national media, with interlocking interests represented in newspaper publishing, the state monopoly radio system, and the Austrian Press Agency. The arrival of German groups, such as the Westdeutsche allgemeine Zeitung , stimulated calls for revisions of media policy, yet Austrian cartel law functioned to protect those conglomerates already in power, such as Mediaprint, and as of 2002 no breakup had occurred. Two years before Austria joined the European Union, the European Court for Human Rights condemned Austria's radio monopoly, ORF. Further impetus toward action came from the need for a legal framework governing the development and use of the Internet as a broadcast medium. While private radio and television existed in Austria in 2002, it did not yet rival the formidable public network. Overall, the thrust of media policy had been to use federal funds to subsidize newspapers, magazines, printing plants, and even the education and training of journalists, rather than to dismantle the media conglomerates and promote stronger competition to diversify Austria's print and broadcast media.

In the early 2000s, protection of the freedom of information attracted greater attention. The Austrian Press Council watched over infringements against freedom of the press or the right to know, which it saw as threatened by military and police security, particularly in the wake of terrorist attacks on the United States in September 2001.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

In the early 2000s, foreign journalists were welcome in Austria and did not need special permission to gather news in the country. Foreign news agencies such as the Associated Press, Reuters, Agence France-Presse, TASS, and the German news agency had headquarters in Vienna. Foreign newspapers were available in the major cities, and foreign radio broadcasts and television stations might be received wherever the country's terrain made reception feasible.

News Agencies

The Austrian Press Agency (APA) founded in 1946 was, as of 2002, the country's leading organization of journalists and reporters and the largest source of information about Austria. The country's national radio broadcast monopoly was its largest shareholder. It maintained correspondents in each of the provincial capitals and at European Union headquarters in Brussels. All of Austria's major newspapers and the Austrian Broadcasting Corporation (ORF) were represented in its governance structures.

As of 2002, it produced over 180,000 news reports annually, covering domestic and foreign affairs, economics, culture, science, education, and sports. It also supplied photographs and graphics for print or on-line media. Its services included data banks, content management, information technology, multi-media services, financial reports, and an original text service, which enabled public relations agencies or offices to send press releases directly into the APA system. It published a financial monitor with news of the Vienna stock exchange. In 2001 its reports were circulated to 37 news agencies, 281 daily papers, 48 weeklies, 171 radio and television broadcasters, and 100 press offices. Its headquarters in Vienna housed the International Press Center, and the agency maintained an important Web site: www.apa.at .

Vienna was also home to the Concordia Press Club, founded in 1859, a professional organization of reporters, editors, and publishers. Concordia gave prestigious annual awards each May for human rights and freedom of the press ( www.concordia.at ). The Austrian Journalists Club ( www.oejc.or.at ), Concordia, and the Austrian Press Agency were all headquartered in Vienna.

Broadcast Media

Austrian radio began in 1924 with the establishment of Österreichische Radioverkehr AG (RAVAG) in Vienna, a corporation whose shares (82 percent) were publicly owned and funded by users' fees. Radio advertising began in 1937, as music and art programming gave way to Nazi propaganda. At the end of World War II, the four Allied Powers established the Austrian Radio Corporation ( Österreichischer Rundfunk , ORF) for radio broadcasts, and television broadcasts began in 1957. Broadcasting was regulated by the federal government rather than the nine provinces, and it was overseen by the Österreichische Rundfunk Gesellschaf t, where proportional representation from several constituencies was intended to ensure fair use of the airwaves. The late 1960s saw new provisions for public citizens to broadcast counter statements if they felt they had been misrepresented on the air. Subsequent statutes also guaranteed journalistic freedom and objective reporting. In 1967 ORF became politically and economically independent. These provisions for its independence were extended in 1974 to ensure objectivity, a wider variety of opinion, and fair and balanced programming. By 1970 ORF consisted of three radio networks and two television channels. During the cold war years, Austrian news was eagerly received in Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia, where many people continued to know German. Unlike the overtly political broadcasts that West Germany aimed at the German Democratic Republic during those years, ORF maintained strict neutrality in radio and television news. As of 2002 ORF maintained regional studios in all nine provinces and broadcasts on four networks, as well as to the United States, Africa, Asia, Australia, and the Near East.

Demand for opening the airwaves to private broadcasters began in the 1980s, a campaign led by the Association of Austrian Newspapers, which expected to own and control most private facilities. Media politics became a hotly debated topic in national elections, and disagreements between the Austrian Socialist Party and the Austrian People's Party over the ownership of frequencies delayed diversification for a decade. Private radio stations did not begin broadcasting until 1988, and then only in Styria and Vorarlberg. Regional and local licenses in the remaining provinces were finally granted and private broadcasting on 43 local networks began there in 1998. Antenne Radio, one of the largest private radio networks, broadcasted in Styria, Carinthia, Salzburg, and Vienna but achieved only modest success. Five years after its founding, Antenne Steiermark (Styria) reached just 24 percent of the regional market.

As of 2002, the result of this gradual liberalization process had not brought significant diversification; the most powerful media players remained dominant. In that year and estimated two-thirds of Austrians watched domestic television broadcasts and 80 percent listen to ORF. Private radio reached only around 15 to 25 percent of the market in its own province and attracted chiefly younger listeners, one-third of Austrians between the ages of 14 and 49. Newspaper conglomerates dominated the private airwaves as well as the country's print media. In 1998 a new Viennese radio station, Wiener Antenne Radio began broadcast, with Die Presse owning a 24 percent share, and another large share in the hands of Fellner publishing. Krone Media, Bertelsmann publishing, the Tiroler Tageszeitung , and Vorarlberger Nachrichten were also major players in regional markets. A ruling prohibiting newspapers from holding more than a 26 percent share in a regional radio station or more than a 10 percent share in two others, which must be in different provinces, was lifted in 2001. In that year Neue Kronen Zeitung established a private foundation to own a majority share in Danube Radio Vienna, broadcasting as 92.9 FM Krone Hitradio . Its one dozen stations reached 5.7 million people, making it a strong competitor of Antenne Radio.

ORF held the largest share in the Austrian Press Agency which prevented it from supplying audio news to private radio stations, thus ensuring ORF's virtual monopoly on the dissemination of news. Its first program, Ö1, broadcasts news headlines three times a day, with longer broadcasts in the evening. The remaining three ORF stations broadcasted a mix of music, talk shows, and cultural reports.

In 1988 ORF, Swiss public television, and Germany's Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen (its second public television channel) joined forces to offer satellite programming for the three German-speaking countries. About 41 percent of Austrian households had satellite television and received about a dozen foreign channels. The most popular were Germany's public television networks Allgemeine Rundfunk Deutschlands (ARD) and Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen (ZDF). Cable television viewers preferred SAT, Pro Sieben, and RTL. Two-thirds received CNN and about one-third received Euronews. Border areas closest to Germany, Switzerland, and Italy also received foreign radio broadcasts, although Austria's mountainous landscape made transmission difficult in some locations.

Each state studio of ORF local television broadcasted a half-hour local news program Mondays through Fridays and headlines as much as five times a day. News and politics consumed about 16-18 percent of television broadcast time, but only about 17-19 percent of television viewers watch the news.

Austria's print and broadcast media often shared journalists and collaborated in formulating media policy. In 1985, for example, ORF and VÖZ agreed to the expansion of radio and television advertising into Sundays and holidays, with the proviso that ORF renounce future broadcasts of regional advertising in local television markets. Another agreement in effect from 1987 to 1995 provided for local daily and weekly newspapers to establish private regional radio pilot programs under the aegis of ORF. This maneuver effectively excluded entities other than newspapers from access to radio.

The Association of Austrian Newspapers generally succeeded in insisting that ORF should be funded by user fees rather than advertising, which accounted for about 42 percent of its revenues in the early 2000s. ORF was also prohibited from airing advertising of a regional nature. ORF's four broadcast networks reached 75.9 percent of possible listeners in Austria (5.3 million people), and private radio served only about 22.8 percent, or 1.6 million. In April 2001 Austria established a new regulatory authority for radio, KommAustria, with jurisdiction over the distribution of private television broadcast licenses and the responsibility to watch over the increasingly interwoven telecommunications networks.

Electronic News Media

Austria was relatively late in developing widespread Internet access, in part because of high telephone rates from the provinces for long-distance calls to Internet service providers. Austria's first Internet sites were produced by universities. Media Analyse , an Austrian monitoring agency, found that in 1999 some 7.4 percent of Austrians had used the Internet on the day preceding their survey, just under a half million people. Computers were still not ubiquitous in Austrian schools, nor were information literacy skills part of the general curriculum. In Vienna, teletext access was also available through cable television for about 220,000 subscribers.

Through the mid 1990s all Austrian dailies established Web sites on the Internet. Der Standard , the first Austrian newspaper to appear online, was still ranked

In 2001 the Association of Austrian Newspapers demanded protection of intellectual property of journalists and reports because electronic news digests supplied headline news on line without crediting the sources and thereby reduced demand for printed papers.

Education & TRAINING

The universities of Vienna and Salzburg had departments of communication and journalism where students could earn a master's degree or a doctorate. (Austria had no real equivalent of the American baccalaureate degree). The University of Salzburg's Institute for Communication Science also prepared an annual report on the state of journalism in Austria. Kuratorium für Journalis tenausbildung (the Board of Trustees for Journalist Training), founded in 1979, was also located in Salzburg and Vienna. Journalists might be admitted to its Journalisten Kolleg (educational programs) after passing an examination; no particular academic degree was required. It offered 12-week training seminars spread over a 9-month period, covering such topics as electronic media, online publishing, interview techniques, and press law.

Until 2001, journalists were represented through the Union for Art, Media, and Freelance Work, Journalists

Summary

Austria's remaining 15 daily newspapers might, as of 2002, face further shrinkage in coming years. Particularly the small dailies, such as Neue Vorarlberger Tageszeitungand the Neue Kärntner Tageszeitung , might be more dependent on the special press subsidy or might become vulnerable to bankruptcy as they face increasing competition for advertising revenues, rising newsprint costs, and higher postage rates which become effective in 2003. Austria's strong system of public transportation would continue to support newspaper readership; in contrast to Americans who commute to work by car, Austrians travel by train, subway, or streetcar, past kiosks where they can buy a daily paper and in vehicles where they can read instead of drive.

Print media appeared subject to change only through economic concerns; an examination of the membership of organizations such as the Association of Austrian Newspapers, the Austrian Press Agency, or the Board of Trustees for Journalists' Training revealed very few women or minorities. Journalism and its leadership appeared to be securely in the hands of the interlocking hierarchies of government, Catholicism, and the established business community.

Significant Dates

- 1988: WAZ acquires a 45 percent share in Krone and Kurier , founds Mediaprint to handle the joint printing, distribution, and advertising sales of its papers.

- 1987-1991: this year marks the end of political party-owned newspapers Arbeiter Zeitung and Volksstim me (KPÖ).

- 1988: Der Standard is launched.

- 1992: Täglich Alles is launched by Kurt Falk in four-color intaglio.

- 1994: Vorarlberger Nachrichten is first traditional Austrian newspaper to print in four colors.

- 1995: Der Standard is first online newspaper in the German language in the world.

- 1995: Wirtschaftsblatt is launched with an initial run of 58,000 copies.

- 1996: Wiener Zeitung loses its monopoly on the publication of government announcements and job postings.

- 2000: Täglich Alles ceases print publication but is still available online.

- 2001: Neue Zeit ceases publication.

Bibliography

Austria: Facts and Figures. Vienna: Federal Press Service, 2000.

Bruckenberger, Johannes. "Zeitungen im Zeitraffer— Chronologie des Medienjahres 2000/01." VÖZ Jahrbuch Presse 2001—Dokumentationen, Analysen, Fakten . Vienna: Verband österreischischer Zeitungen, 2001. http://www.voez.at/dynamic .

Burtscher, Klaudia. "Between Sensationalism and Complexity: A Statistical Analysis of the Environment as a Topic in Austrian Media." Innovation: The European Journal of Social Sciences, 6 (1993): 519-532.

Düriegl, Günter and Andreas Unterberger. Die Presse, ein Stück Österreich. Vienna: Vienna Historical Museum, 1998.

Geretschlaeger, Erich. Mass Media in Austria . Vienna: Federal Press Service, 1998.

Grisold, Andrea. "Press Concentration and Media Policy in Small Countries; Austria and Ireland Compared." European Journal of Communication, 11 (1996): 485-509.

Hummel, Roman. ""A Summary of the Media Situation in Austria. "" Innovation: The European Journal of Social Sciences 3 (1990): 309-331.

May, Stefan. "Kein Mensch schaut uns an: Österreichs Medien in Deutschland." Academia, 52 (2001): 10-12.

Pfannhäuser, Harald. "Formil macht mobil." Academia, 52 (2001): 7-9.

Pürer, Heinz. "Österreichs Mediensystem im Wandel." Presse Handbuch, 1989: 5-15.

—— Presse in Österreich. (Schriftenreihe Medien & Praxis, Band 2). St. Polten: Verband Österreichischer Zeitungsherausgeber und Zeitungsverleger, 1990.

Sandford, John. The Mass Media of the German-Speaking Countries. London: Oswald Wolff, 1976.

Verband Österreichischer Zeitungsherausgeber und Zeitungsverleger. Presse Handbuch. Vienna: annual volumes.

Helen H. Frink

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: