Canada

Basic Data

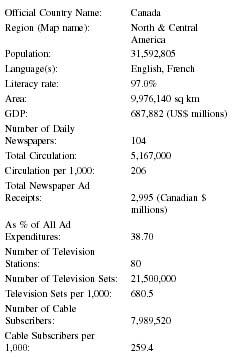

| Official Country Name: | Canada |

| Region (Map name): | North & Central America |

| Population: | 31,592,805 |

| Language(s): | English, French |

| Literacy rate: | 97.0% |

| Area: | 9,976,140 sq km |

| GDP: | 687,882 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Daily Newspapers: | 104 |

| Total Circulation: | 5,167,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 206 |

| Total Newspaper Ad Receipts: | 2,995 (Canadian millions)$ |

| As % of All Ad Expenditures: | 38.70 |

| Number of Television Stations: | 80 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 21,500,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 680.5 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 7,989,520 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 259.4 |

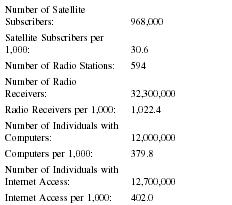

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 968,000 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 30.6 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 594 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 32,300,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 1,022.4 |

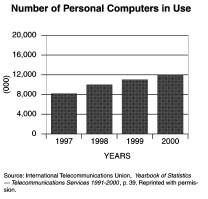

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 12,000,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 379.8 |

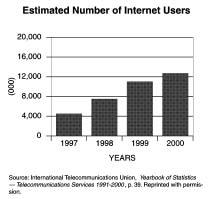

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 12,700,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 402.0 |

Background & General Characteristics

Canada is a very large country, at least in terms of landmass. It extends over nine million square kilometers. The largest single administrative entity is Nunavut, an Arctic territory that constitutes 21 percent of the nation's landmass while having its smallest population, 28,200. In contrast, Canada's largest central provinces of Ontario and Québec have a combined population of 19,281,900. These two provinces are the nation's largest media market, and constitute 26.2 percent of the country's land-mass. Canada borders on three oceans: the Atlantic, the Pacific and the Arctic. Its most immediate neighbor is the United States, which it touches on two borders, one to its south and the other to the north. Nine out of 10 Canadians live within ninety miles of the United States. In terms of density, in the majority of the country there is less than one person per 49 square kilometers of land space. Sharing to a significant degree a common heritage and a common language with the United States, issues focusing on national cultural survival dominate much of the political debate in Canada. Media issues and press policies are critical players in this debate. The arguments have become more acute since Canada joined the United States in a free trade agreement in 1984 and agreed to extend the arrangement to include Mexico in 1988.

Europeans came to what is now Canada in the early 16th century as agricultural and industrial revolutions on the continent left hundreds of thousands of displaced persons searching for new lives and new endeavors. In 1534 the French master pilot Jacques Cartier left the port of Le Havre in command of two ships and 61 sailors, anxious to inquire about economic and settlement prospects in a new and unfamiliar world which had been seen some 40 years previously by explorer John Cabot. Cabot's discoveries led to the establishment of the Newfoundland and Atlantic fisheries, but anything beyond sporadic settlement had yet to take place. Cartier was determined to explore all opportunities, so he sailed beyond where the Atlantic fishery was located, having become a mainstay in the economic life of continental Europe. That year, Cartier explored the many islands, bays, and inlets which dotted the shoreline of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, but he would have to wait until his second voyage to the New World in 1535 before sailing down the river which drained into the Gulf.

Cartier hoped to find a civilization that could trade with or perhaps rival that of Europe. What he discovered instead were two very poor native settlements, one on the current site of the city of Montréal and the other at the contemporary city of Québec. He came to the conclusion that this was a land for the taking and between 1541 and 1543 worked diligently to encourage settlements in the frontier. The hostile climate and lack of interest would prove to be fatal for Cartier. It would remain for others to complete the work that Cartier had begun.

The Atlantic fishery moved closer to shore when drying part of the catch became a necessity for preservation, and contact with the native communities along the St. Lawrence shores became more frequent. The aboriginal settlements possessed furs, a commodity valued by the Europeans. Realizing the value of fur in the European market place, many fishers gave up the ocean to explore the economic potential of the vast beaver population. Canada had launched its first and most important economic enterprise, one that would last well into the early years of the 19th century. As the Canadian economic historian Harold Innis noted in his study of the fur trade, the wholesale exploitation of raw products, which began with the beaver, set Canada on an economic path which focused on the extraction of the raw materials that Innis referred to as staples. With the fur trade came an increased need for settlements and established economic ties to Europe. Trapping required alliances with the native populations who, like the French, prospered until overkill forced the trade westward to the rivers of the great plains provinces of contemporary Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta, eventually reaching the North West Territories, where the cost put the price of furs beyond the reach of traditional consumers in Europe.

Despite France's loss of Canada to Britain in 1759, the presence of the French in Canada has had a lasting impact. French remains the official language in the province of Québec and enjoys significant legal and practical status in New Brunswick, Ontario, Manitoba and parts of Western Canada. It has equal status with English in all federal jurisdictions such as Parliament and the judiciary system. Québec still retains the core aspects of the Napoleonic civil code. The linguistic arrangement that was forged between the British and the French following the conquest of 1759 remains reflected in the media in contemporary times.

There is no evidence to suggest that the French colonies at Québec had any interest in journalism or the press. In fact, there is no evidence to suggest that printing existed in the colony prior to the British conquest in 1759 although there is some suggestion in historical texts that religious tracts were published for the literate minority. The majority of colonists were farmers and skilled crafts people who labored under a form of continentally inspired feudalism that faded with the British invasion. The lack of journalistic development in the French colonies put Canada nearly a century behind the soon to be independent United States in the link between the press, government, democracy and an educated citizenry.

The emergence of journalistic practice took place in the British possessions before the conquest of Québec and the successful rebellion of the thirteen colonies. The first newspaper of record was Benjamin Harris' Publick Occurrences Both Foreign and Domestick which appeared in Boston after Harris left a British debtors prison and immigrated to America. Harris, a well-known agitator, incurred the wrath of the colonial authorities and his newspaper did not survive beyond one issue. In 1735, a civil jury dismissed a charge of criminal libel against Peter Zenger, a German immigrant who had founded and published the New York Weekly Journal. Zenger was brought to court for an inflammatory article he had written about the Governor of New York. With the dismissal of the case, the concept of free speech, democracy, and a free press became incorporated in the political culture of western society. The simple equation that a democracy cannot exist or function properly without a free press was born out of the Zenger decision. The case would not mark the end of attempts by both business and industrial elite to control the distribution and content of the daily press, a problem which continues to exist on both sides of the border today.

Journalism came to what was to become Canada just a few years before Britain lost her thirteen colonies to the new republic of the United States. A Bostonian, Bartholomew Green, moved up the coast to Nova Scotia where he opened a printing concern and announced that he would soon begin publishing a newspaper. Green died before he could launch his new journal, but his work was soon assumed by an old Boston compatriot, John Bushell, who published the first edition of the Halifax Gazette in 1752. As Canadian historian Douglas Fetherling has noted, Canadian journalism was born with the launch of this newspaper.

Printing and newspaper publication got a boost after 1776 when Loyalist printers flooded Canada. Twenty newspapers were founded by the end of the War of 1812 with a combined circulation of 2,000 copies. Of these, five were published in what is now Québec, one in what is now Ontario and the remainder in the Atlantic provinces and other territories. Douglas Fetherling notes that these papers were primarily "journals of ecumenical rationalism, full of scientific and literary materials picked up from foreign publications and used to fill the columns between the official proclamations and what in some cases amounted to plentiful advertising, much of it related to land sales, shipping schedules and the like."

By 1836, mechanical printing presses were being manufactured in Upper Canada. There were now 50 newspapers operating in Ontario and Québec with Ontario leading the way with 60 percent of the journals located in that colony. Journalism was becoming seriously involved in the political life of the citizenry. The population had split between Tories, rooted mainly in the Loyalist communities who had come to Canada to preserve their monarchial connections and Reformers unwilling to separate church and state. The colony's newly founded newspapers found themselves dividing along political lines.

William Lyon Mackenzie changed the course of Canadian journalism, specifically its relationship to the ruling classes. Mackenzie was a political and economic liberal who had great difficulty abiding the colonial government, which he labeled "The Family Compact." Very few of the ruling elite could claim blood ties to the British monarchy, Mackenzie claimed that they behaved as royalty, and thus the name. Mackenzie was an admirer of William Cobbett, the English journalist and reformer who published parliamentary debates. Cobbett's name regularly appeared when one spoke of the impact of the 1832 Reform bill and the Chartist movement. He was also connected to the American president Andrew Jackson, who was no lover of the currency and banking system. Cobbett published the Colonial Advocate for ten years between 1824-34. In 1836 Mackenzie began publishing the Constitution which he devoted to the coverage of serious news. He was also plotting to carry out a violent rebellion in league with French speaking rebels led by Louis-Joseph Papineau. Their joint efforts led to the outbreak of armed confrontation in December 1837. Within hours of the beginning of the uprising, the rebels were routed and Mackenzie had to flee to New York to save himself from the gallows.

The Mackenzie-Papineau rebellion was not without positive results. In May of 1838, John George Lambton, Earl of Durham, arrived in Québec City with a mission to investigate and report on the problems that led to the ill-fated rebellion. In the winter of 1839 Durham issued one of the most important documents in Canadian history, the Report on The Affairs of British North America. It would have a serious impact on developing Canadian press policy, in particular the relationship between a citizenry and its government and the role that journalists assume as the information intermediaries of this relationship. Although Durham commented on a number of Canadian problems, in particular the thorny relationship of the English and French speaking communities, the majority of his report was devoted to dismantling the semi-feudal rule of the Family Compact and its allies and the installation of a representative democracy.

In 1867 the British Parliament united Ontario, Québec, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia with the British North America Act. The legislation made no mention of the role of the press, and, unlike the American Constitution, it did not contain a bill of rights. Canada would not have its own constitution until 1982. Between the passage of the British North America Act and the arrival of radio in the early twentieth century, the press in Canada enjoyed one of its most productive periods.

Following Confederation, the federal government adopted a policy to extend the nation from Atlantic to Pacific. British Columbia joined the union in 1870 when the federal government promised to build a railway from Montréal to Vancouver. Eventually, the territories located between Ontario and British Columbia and owned by the Hudson's Bay Company were turned over to Canada, from which three new provinces and three new territories were carved. The 10 year old Victoria Gazette and the Anglo American and the French language Le Courier de Nouvelle Caledonie (Nova Scotia Courier) and the British Colonist existed on the west coast to serve the growing population. Newfoundland and Labrador followed in 1949.

The 1857 A. McKim Directory of Newspapers listed 291 publications available in Canada. By 1900 this number had increased to 1,226, of which 121 were daily newspapers. Along with this growth the characteristics of the press changed considerably in the second half of the nineteenth century. In many respects, newspapers abandoned the pointed and sometimes vitriolic partisanship that was symbolic of the newspapers of the first half of the century. The political position of the paper was more likely to be found on a page dedicated to editorial opinion. There was no mistaking that the Toronto Globe supported the Liberal Party and the Toronto Telegram supported the Conservative Party. The most significant change to come out of the nineteenth-century Canadian media was the evolution of the press from primarily weeklies to dailies and the entrenchment of newspapers in the rapidly developing technological and market economy. The country also took its first steps to becoming a new, urbanized society. From 1900 until 1911, Canada was the fastest growing nation in the world. Newspaper circulation in 1900 stood at 650,000 and it doubled by 1911. The Canadian growth was only truncated by the First World War.

Once the First World War ended the country entered a crippling depression that lasted until 1921. Relative prosperity followed and new technical innovations made Canadian newspapers more efficient. The cost of wire services such as Canadian Press and the Associated Press in the United States decreased significantly when the teletype was introduced. In many ways, more efficient technologies only benefited a few relatively solvent publishers and owners. While there were 121 dailies in the country in 1900, by 1951 this had dropped to 94. In 1900, 18 Canadian urban areas published two or more dailies. By 1951, only 11 Canadian cities would have competing newspapers. Since 1960, several major Canadian newspapers have closed their doors including the Toronto Telegram, the Montreal Star, Ottawa Journal and the Winnipeg Tribune. This decline was partially offset by a new series of tabloids published under the Sun masthead in Toronto, Winnipeg, Ottawa, Calgary and Edmonton. Other new ventures began in Halifax, Montréal and Québec City. In 1998, the Hollinger corporation converted its business newspaper The Financial Post into a daily operating under the masthead of the National Post. It is now a member of the Can West Global communications corporation.

In the early 1970s the use of computers in the news-room not only sped up the production and editing process, it succeeded in destroying the power of one of the country's oldest unions, the International Typographers Union (ITU), an organization that fiercely resisted the introduction of digital technology into the newsroom. As early as 1964 the ITU struck all three Toronto dailies, The Globe, The Star and The Telegram to fight the introduction of computers in the newsroom. By 1987, the Toronto Star which had at one time employed more than 150 unionized typographers, had reduced the staff to 30. The arrival of digital technology has changed the concept of reporting and newspapers themselves.

Canada's federal government is a constitutionally structured bilingual parliamentary monarchy, both English and French are equals in any federal jurisdiction. Each province can decide whether to be officially bilingual or not which can result in an odd combination of polices. Québec is the only officially unilingual Canadian province with French as its official language. Although French is not among the official languages of Ontario, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia its use is widespread. New Brunswick is the country's only official bilingual province. Ontario government documents are usually issued in both languages. The Ontario province government-owned television system offers full time English language service on TVOntario and full time French language service on TFO, Télévision Français d'Ontario . On the national level the government owned and operated Canadian Broadcasting Corporation—La Société Radio—Canada operates two radio and two television networks. Canada also has an official multicultural policy so that the political and judicial structures address the needs of those outside the French and English communities and the aboriginal populations.

Canada has a population of more than 31 million, 68.6 percent of which are between the ages of 15 and 64. Like many other western industrial nations, Canada faces an aging society in the coming decades of the twenty-first century. There are now 3,917,875 persons over the age of 65, constituting 12.6 percent of the population. Although it constitutes the smallest demographic range, it is not far off the 18.8 percent of the population between the ages of 0 and 14. The majority of Canadians live within a narrow corridor bordering on the United States of America.

Although Canada has a vast land area, the highest concentration of the population, or around 35 percent, lives in the central Canadian provinces of Ontario and Québec. The western provinces, especially Alberta and British Columbia, with their staple products of gas, oil, and forestry products, have proven attractive to those wishing to move. Combined, Alberta and British Columbia constitute about 12 percent of the Canadian population. The remainder live either on the prairies, in Atlantic Canada, in the Northwest Territories or in Nunavut.

The 1996 Canadian Census recorded the immigrant population in the country. There were 4,971,070 persons who reported that they had been born outside the country. Of these 1,054,930 arrived before 1961. A further 788,580 came between 1961 and 1970. The number of immigrants began to climb again in 1971. In the subsequent decade 996,160 persons arrived. This number increased to 1,092,400 in the ten years following 1981. In the final decade of the twentieth century, 1,038,990 persons immigrated to Canada.

The most significant increase in the immigrant population was comprised of those who identified Eastern Asia as their home area. Only 20,555 of these people reported coming before 1961. But in contrast, 252,340 arrived at Canadian ports between 1991 and 1996. A further 140,055 reported coming from Southern Asia and 118,265 reported that they came from Southeast Asia. The main ports of attraction were in Vancouver and other points on the Pacific coast and the central Canadian city of Toronto. African, Caribbean and Middle Eastern immigrants also significantly increased in number during the same years. Canada during the past four decades is decreasingly a white, Anglo-Saxon, and predominantly Christian state.

Despite immigration from areas of the world where English is primarily a second language, it is still claimed by 16,890,615 Canadians as their mother tongue. A further 6,636,660 Canadians reported French as their mother tongue. A total of 4,598,290 persons reported speaking a third tongue, which was not classified as official. These included persons who came from China, Italy, Germany, Poland, Spain, Portugal, India and Pakistan, the Ukraine, Saudi Arabia, Holland, the Philippines, Greece, and Vietnam. Inside Canada, both Cree and Inuktitut were recognized as third, nonofficial languages. There were 1,198,870 more who reported speaking languages other than English, French, or those listed in the nonofficial columns of the census reports.

There are a number of media outlets directed to populations whose primary language is neither English nor French. As one of Canada's oldest multilingual broadcasts, Toronto radio stations CHIN-AM and CHIN-FM have continued since the mid-1960s. Multilingual television station CFMT-TV serves not only Toronto, but also communities in southwestern Ontario through a system of satellite transmitters and cable companies, most of which are owned by Rogers Communications. Canada's large Asian population can subscribe to the cable pay service Fairchild TV in most parts of the country. Toronto's large and well established Italian community is served by the daily Corriere Canadese. There is an established practice that broadcasting stations operating primarily in one of the country's two official languages offer programming in a third language. Toronto's local CITY-TV still follows this practice.

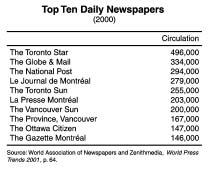

The Canadian newspaper industry has found a niche in the complex, multicultural, and multilingual Canadian media market. Ranging from punchy, colorful tabloids such as the Sun newspaper, to the more intense and serious National Post, Le Soleil, and the Globe and Mail . Fifty-seven percent of all Canadians read a newspaper daily in 2001, according to the Canadian Newspaper Association. This represents 11.8 million readers which is an increase of 3 percent over the 11.3 million readers who had reported reading a newspaper daily in the year 2000. This reversed a downward trend of the previous two decades.

The statistics become more revealing when broken down into separate demographic categories. In the major markets of the country, there are 4.8 million adults between the ages of 18 and 49, 85 percent of which reported reading a newspaper at least once a week. Younger readers

Of cities with a population over 150,000, the Manitoba capital of Winnipeg reported the highest weekly newspaper readership with 89.9 percent of its citizens over the age of 18 having read one in the past week. Calgary, Alberta and Windsor, Ontario were tied for second place at 89.5 percent each. The Alberta provincial capital of Edmonton was 87.7 percent. Hamilton, Ontario reported reading at 87.2 percent and Halifax, Nova Scotia was at 85.5 percent. St. Catharines, Ontario, Regina, Saskatchewan, Québec City, Québec, and Victoria, British Columbia were all over 84 percent. In larger cities, readership has remained fairly constant. In many ways, the Ontario provincial capital of Toronto reflected the trends. Of adults over the age of 18, 56 percent reported that they had read a newspaper the previous day. A further 77 percent reported reading a newspaper at least once per week and 84 percent reported having done the same by the end of the week. Figures were similar for Montréal. In the category of having read a newspaper the previous day, the figure stood at 48 percent of all adults. In the category of having read a newspaper at least once per week, the number was 68 percent and finally, those reporting having read a newspaper by the end of the week, the figure stood at 79 percent. In British Columbia's largest city, Vancouver, the numbers stood at 56 percent, 77 percent and 79 percent respectively. The national capital city of Ottawa reported 57 percent, 79 percent and 84 percent respectively, in figures released by the Canadian Newspaper Association.

The largest owner of Canadian newspapers is Southam Publications (Can West Global) with 27; next is Osprey Media Group Inc. with 18; Sun Media (Quebecor, Inc.) owns 15 papers. Hollinger Canadian Newspaper Limited Partnership owns 10 and Power Corporation of Canada owns seven. The next largest all own five papers each: Independents, Horizon Operations BC Limited, and Torstar Corporation. Annex Publishing and Printing own two. Bell Globe Media and Black Press each own one newspaper.

Canadians claim that they have the oldest surviving newspaper in North America. The Québec Gazette, once the voice of the provincial capital's then extensive English speaking population, began publishing on June 21, 1764. It was eventually folded into the present-day weekly publication, the Québec Chronicle-Telegraph. The next oldest publication is the Southam-owned Montréal Gazette, which began publication on June 3, 1778. It is the longest continuing daily in the country.

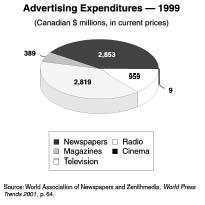

Newspapers in Canada continue to hold their own in attracting advertising dollars. In 1996, they secured 32 percent of the overall market in contrast to television's 32.3 percent. In 1997, the figure increased slightly to 34.1 percent in comparison to television's 31.1 percent, but it began to decline again as the turn of the century approached, with 32.4 percent of the market in comparison to television's 31.5 percent. However, the volume of dollars attracted, expressed in millions, did continue to increase, from $1,960 (Canadian funds) in 1996 to $2,303 in 1997 and finally $2,379 in 1998.

Economic Framework

In the spring of 2002, 66.6 percent of all Canadians over the age of 15 were participating in the labor market. Viewing the statistics on a province to province basis shows some disparity. Participation rates are highest at 72.2 percent in Alberta, a province wealthy from extensive gas and oil royalties. The participation rate is the lowest in Newfoundland and Labrador, where the economy for years was built on fishing in the Atlantic. It is only in recent years that economic diversification has been attempted, with oil and gas exploration on the Hibernia grounds at sea and through hydro electric development at Churchill Falls in Labrador.

Since 1997, the country's unemployment rate, seasonally adjusted, has dropped significantly. That year it stood at 9.5 percent across the nation and in 2002 it stood at 7.2 percent. Again, the statistics must be seen in their relationship to the country's provinces. The rate for Newfoundland

In March of 2002, Canada's Consumer Price Index stood at 117.7, based on the index start date of 1992 of 100. Between March 2001 and March 2002, the overall index increased only 1.8 percent. However, that figure is somewhat distorted because tobacco and alcohol products increased by 14.8 percent. Food was also higher, increasing by 3.3 percent over the same period. Only two categories showed a decline, one of which was clothing and footwear (although the decline was insignificant at 0.7 percent). The cost of energy actually declined by 3.3 percent. Shelter and recreation, education and reading all increased 1.1 percent. Household furnishings and operations increased by 2.2 percent, transportation by 0.3 percent, and health and personal care by 0.9 percent. Compared with incomes in 1992, the relative purchasing power of the dollar in March 2002 was 85 percent.

While personal disposable income in Canada increased by 3.3 percent from the fourth quarter 2000 to the fourth quarter 2001, corporate profits declined by 29.9 percent. The gross domestic product at market prices seasonally adjusted at annual rates (SAAR) declined by 0.1 percent. Business investment in machinery and equipment declined by 5.6 percent. Personal expenditure on consumer goods increased by 2.3 percent. Overall, personal savings rates declined by 0.3 percent.

All Canadian media outlets experienced growth in advertising revenue in the years between 1996 and 1998, the last year figures are available. The numbers below are expressed in millions of dollars in Canadian funds. Spending on advertising in all major media increased from $6.1 to $7.3. Newspapers increased their share from $1.9 to $2.3. Television jumped from $1.9 to $2.3. Radio thought to be on its way out as a major medium in Canada in the early 1990s actually attracted $.9, an increase from $.7 two years earlier. General magazines increased from $.31 to $.38. Trade magazines increased from $.233 to $.277. Outdoor advertising increased from $.200 to $.250.

Press Laws

In 1982, the Government of Canada repatriated the British North America Act from the parliament at Westminster. Although many of the clauses of the new Canadian constitution did not vary significantly from those of its predecessor, it did include a Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Under those matters deemed to be fundamental freedoms the role of the press was defined for the first time. The four basic freedoms that emerged did not exist in the British North America Act. These were defined as: freedom of conscience and religion; freedom of thought, belief, opinion and expression, including freedom of the press and other media of communication; freedom of peaceful assembly; and freedom of association.

Freedom of expression and freedom of the press, although similar and related concepts, are not one-and-the-same in Canadian law. In fact, serious limitations exist which clearly differentiates freedom of the press in Canada from that of its southern neighbor. The Charter of Rights and Freedoms only defines those rights of the individual in his or her relationship to the state. As law scholar Robert Martin has pointed out, the law does not address freedom of expression issues that arise involving media owners and managers.

As noted earlier, Canada is a constitutional monarchy consisting of ten provinces and three territories. The federal parliament consists of a lower chamber, the House of Commons, whose members are chosen by the electorate in a cycle that must not exceed five years. The federal electoral districts called ridings are loosely defined on the basis of population. At the turn of the most recent century, five parties sat in the House. The Liberal Party had the largest number of members and thus formed the government with its leader assuming the role of Prime Minister. The largest opposition party is the Canadian Alliance. Minor parties include the New Democratic Party, the Progressive Conservatives and Le Bloc Québeçois. Although rare, there are occasions when members sit without party affiliation. The upper chamber is the Canadian Senate, which represents the interests of the provinces. Members are appointed on the recommendation of the Prime Minister with the consequence that a long sitting government may have a majority of members in both houses. Senators must retire by the age of 75. The head of state is the Governor-General who acts as the representative of the Queen in Canada. Although constitutionally endowed with extensive powers, the actual role of the Governor-General is largely ceremonial, although no piece of legislation in Canada becomes law without his/her signature.

The 10 Canadian provinces hold considerable powers such as control of health, welfare and education, which make them virtually independent states inside the confederation. Their powers are defined in Sections 92, 92A and 93 of the constitution. Federal powers, which tend to be national in scope, can be found in Section 91. Section 95 defines those areas in which both levels of government may make law, in particular in areas such as agriculture and immigration. Some of the most important clauses in the constitution are contained in Section 33 known as the "not withstanding clauses" which allow any constitutionally enabled government to override court decisions for a five year period after which the enacting government must give adequate justification for continuing to use the clauses. One such case was when Québec language laws, which gave preference to the French language, were declared unconstitutional.

Because the British North America Act was written in 1867, some technologies were not addressed, such as broadcasting. In 1929 the French-language province of Québec passed legislation to regulate broadcasting within its borders. The federal government retaliated by taking the matter to court. In 1932 the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council decided that broadcasting was a matter of national interest and therefore under the jurisdiction of the federal government. Also at this time, Canada had entered into treaties with both the United States and Mexico regarding allocation of broadcast channels. Section 132 upheld the right of Canada to make such treaties, thus confirming federal jurisdiction in this media field.

As in most modern democracies, Canada has a series of laws pertaining to defamation. Virtually all of them have something to do with press coverage of certain events. The most common set of statutes is referred to as "civil libel laws," although the definition for criminal libel still exists on the books. In some jurisdictions, the definition distinguishes between slander and libel that is written or portrayed. In other jurisdictions, the word defamation is used to define all kinds of libel. In Canada, anything presented by a media outlet is subject to potential action under the law. This includes news, classified ads, advertisements, comic strips, and even the publication of materials from outside sources.

Criminal libel is divided into three categories: seditious libel, defamatory libel, and blasphemous libel. The clauses have traditionally been used to clamp down on political speeches. The last case involving seditious libel took place in the 1940s when the Jehovah's Witnesses delivered a tract accusing the Premier of the province as being a God-hating demagogue. When the case finally arrived at the Supreme Court, the judges divided five to four in throwing out the case against the sect. As a consequence of that decision, it is now virtually impossible to get a conviction on the charge.

The definition of defamatory libel is similar to civil libel, but can result only when two persons decide to exchange inflammatory words leading to a confrontation. As Robert Martin points out, the law was first passed by the British Star Chamber in the seventeenth century to discourage debates from descending into duels. In Canada the most famous case took place in the 1930s when a man in Edmonton distributed a pamphlet with the names of nine prominent persons on one side of the sheet listed under the title "Bankers' Toadies." On the other side, he wrote the words "God Made Bankers' Toadies just as He made snakes, slugs, snails and other creepy crawly, treacherous and poisonous things. Never therefore abuse them—just exterminate them." He was arrested, tried, and convicted of defamatory libel.

Blasphemous libel has much to do with religious practice. The statute allows for serious religious debate but not for the defamation of religious belief or those who hold views that may be controversial. There has never been a case under this law in Canada, but in Britain a decision ruled that only the Christian religion need be defined under this law.

Censorship

Libel action in the minds of some observers can be used as a censoring device in the hands of those with the ways and means to hire expensive lawyers. In the mid-1980s it was rumored that two wealthy business families in Toronto had sent letters threatening legal action to authors who were writing about their respective family histories. However, this does not appear to be a large or significant problem in Canada. Surveys by the Canadian Daily Newspaper Association throughout the 1980s clearly demonstrated that few had serious concerns about large lawsuits. In Canadian law, an apology will officially end any libel action. In many cases, the defendant can ask the court to impose expensive bonds on a plaintiff that that person runs the risk of losing. Favorable court decisions result in low awards that won't cover the expenses incurred.

There are two levels at which censorship operates, in the boardrooms of media outlets and in the judicial system. The first is easy to define since it has historical precedents. The first media in Canada were established with clear, political objectives in mind, namely the support of the patron who paid the way. When newspapers evolved into independent entities supported by advertising in the late Victorian period, they gave the illusion of being politically independent. Yet many of these journals were operated by strong willed individuals who used the media to promote personal causes, some of them beyond politics. Joseph "Holy Joe" Atkinson of the Toronto Daily Star was an adamant temperance man who forbid liquor advertising forbidden in that newspaper. A policy that lasted for a number of decades after his death. Opposing views on the question did not appear with any regularity in Atkinson's newspaper. In another example, there was little doubt that the mission of the French language journal Le Devoir during the First World War was to prevent Canada from being involved in what its founder Henri Bourassa viewed as Britain's war in Europe.

In more recent times, the relationship between the press and the judiciary has become a flashpoint of controversy. Courts regularly prohibit the publication of evidence. In a notorious murder case that took place in St. Catharines, Ontario, a young couple kidnapped, tortured and murdered two young schoolgirls. The proceedings against the female defendant were closed to the media. She had arranged for a plea bargain to two counts of manslaughter in return for her testimony against her husband. The trial judge ruled that public exposure of the conditions of her plea bargain could possibly contaminate the proceedings against her husband. A series of videotapes of the kidnapped girls were also suppressed. In other cases, such as the need to protect witnesses, Canadian courts regularly forbid the publication of certain types of information.

One of the more interesting cases in Canadian history surrounds the revision of the statutes governing the behavior of juvenile defenders and the consequent introduction of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982. The Juvenile Delinquents Act states that trials of juveniles must take place without publicity. In 1981, a Supreme Court decision declared that all persons involved in any specific case against a juvenile had to remain anonymous. Trials were to be held in camera, defying the public nature of the judicial system. When the Charter of Rights and Freedoms became law, the Ottawa Citizen sent a reporter to cover a juvenile case. She was turned away. In the end, the Supreme Court upheld the right of public access to judicial proceedings but it also upheld the right of a juvenile accused of a crime to anonymity.

The most restrictive piece of legislation for the Canadian media was passed in 1914 under the title of the War Measures Act. It was to be used in only the direst of circumstances because its key initiative was to remove the law making right of Parliament and to transfer it to the federal cabinet. Citizens' participation in government was therefore suspended and censorship legalized. It was first enacted in 1914 when Canada joined Britain in the First World War. Although the war officially ended in 1918, the law remained in effect until 1920.

The government used the law to ban publications during the war years. Among these were a number of German language publications, but socialist and social democratic magazines and newspapers were also banned, as well as a few Irish nationalist publications. Any publication that questioned the direction of the war could potentially be banned. Publications advocating temperance were also banned on the premise that such journals would weaken the morale of men overseas. The Act resurfaced in 1939 when Canada went to war against Germany. As in the First World War, the provisions of the act continued on for two years after the hostilities ceased.

The most controversial application of the law came in October 1970. Québec had been the scene of disturbances over the right of the province to secede from the Canadian Confederation. The debate began in the mid-1950s and escalated in the early 1960s. Terrorists using the name FLQ ( Front de Liberation Québeçois ) placed bombs in a mailbox in the English speaking district of Westmount and threatened other English language institutions. In 1970 they kidnapped the British trade minister, James Cross, and the provincial minister of labor, Pierre LaPorte. Cross was eventually released but LaPorte was murdered by his captors, which led Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau to invoke the Act. No significant armed insurrection appeared and the Act was eventually revoked. When the City of Vancouver used the Act to clean up the downtown from various types of undesirables, the government amended the legislation to allow for regional imposition and changed its name to The Emergencies Act. However, provisions for media censorship are still in the law.

A few Canadian journalists have also run afoul of the Official Secrets Act. In 1979 a Toronto journalist, Peter Worthington, became convinced that there was an extensive Soviet spy network in Canada and that the government was ignoring it. He had come into possession of documents that supported his case and he published one of these in the Toronto Sun. As a result, he was charged under the Official Secrets Act. However, he was acquitted of violating the Act when the judge decided that although the material Worthington published qualified under the provisions of the law, the document was no longer secret. The prosecution in the case decided to let the matter drop.

State-Press Relations

In Canada, the state and the media have never been completely separated, even during the short period between 1919 and 1932 when the emergence of radio broadcasting was primarily a private affair. The tradition of state and press integration can be traced to the evolution of a strictly partisan press in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. As noted earlier, even when the press freed itself from direct party control, most newspapers and many magazines remained outlets for, if not totally partisan political views, at least polarized moral issues such as temperance and women's rights. When broadcasting entered onto the scene in the 1920s, the only state involvement was the issuing of radio licenses through the Department of Marine and Fisheries. However, in 1929 the relationship was to undergo radical change.

As the twenties came to a close, Canadian political elite became increasingly concerned that the commercial messages and entertainment-driven values from American radio stations that freely drifted across the border were eroding Canadian culture. The most popular radio show in Canada was the American produced situation comedy Amos n' Andy. In 1929 the Liberal government of Mackenzie King commissioned three men to study and report on the state of broadcasting in the country, beginning a relationship between the state and the media that has not weakened since. The three were Sir John Aird, a banker, Charles Bowman, a journalist with the Ottawa Citizen, and Augustin Frigon, an engineer at L'Ecole Polytechnique in Montréal. The commissioners studied virtually every form of radio broadcasting in existence during the year of the investigation.

By the time Aird delivered his report, the Liberals were out of office and a new Conservative Prime Minister, R. B. Bennett was in control. It was up to Bennett to decide which form broadcasting would take in Canada. Like King, Bennett was deeply concerned that American influence, especially its views on liberalism and republicanism, would soon dominate Canadian thinking. But in spite of his own concerns, he did not opt for a pure system of public broadcasting. Instead, his government founded the Canadian Radio Broadcasting Commission (CRBC) with a mandate to both build and operate stations and to produce programming for its own outlets, as well as the private sector. The concept proved unworkable.

Badly injured politically by the Great Depression, Bennett was out of office in 1935 and King returned with a vision for a stronger and more Canadian oriented public broadcasting system. The King government essentially threw out Bennett's legislation and created the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) in 1936. The CBC was to own and operate stations, produce programming for both itself and the private sector, but, above all, it was to act as a regulator for the private sector which remained subservient, but intact.

Although the CBC was designed to act as an outlet for Canadian ideas and Canadian programming, radio dials remained tuned to stations south of the border. In fact, the CBC itself carried a significant amount of U.S. programming to help pay its bills. American influence also extended to the stage, film, dance, and music worlds, as well as to publications on a myriad of themes. As the Second World War came to a close, government officials began to realize that the CBC alone could not encourage or preserve what "produced in Canada" culture existed. As a consequence, the government called upon Vincent Massey, brother of the actor Raymond Massey, to conduct an inquiry into the state of the arts in Canada. In 1951 the Massey commission concluded with the now familiar "the Americans are taking us over" theme. The commission concentrated its investigation on the state of the arts, but did note that newspapers were critical actors in the dissemination of knowledge in any given country. In reference to radio, Massey concluded that the medium had three critical functions: to inform, to educate, and to entertain.

In spite of Massey's warnings, American influence in Canada continued unabated. This was assisted in part by the 1948 arrival of television in the United States, four years prior to the opening of the first Canadian station in Montréal. Following a pattern established in radio some three decades previously, television dials in Canadian cities began to lock on to U.S. channels. It was hardly a rebellion against nationalism. In fact, when the dust began to settle over the question as to whether loyal Canadians would reject American broadcasting, the issue had really became one of variety. It remained to be seen whether or not the CBC should remain the dominant provider of broadcasting product in Canada. The answer was a firm no.

Yet another commission had been looking into the business of broadcasting in Canada. Robert Fowler delivered his report to the government on March 15, 1957. It was here that the principle of a single broadcasting system consisting of both public and private participants first saw the light of day. Although Fowler felt that private broadcasters in general had to be forced to deliver a good product or lose their respective licenses, he also conceded that the private sector, in spite of having existed in a subordinate position for twenty years, had refused to go away. To this end, Fowler added one more condition to the purpose of broadcasting, essentially creating a vehicle for advertising. His most dramatic recommendation was the removal of the regulatory powers of the CBC, which he felt should be seated in a neutral body. In 1958, the federal government acted on his proposal and created the first independent regulatory agency, the Board of Broadcast Governors. Within months, the new agency opened the way for private, independent television stations to take to the air. It was the beginning of the alternate development in Canadian television which would see the emergence of CTV (Canadian Television) as the country's first privately owned and operated system.

Broadcasting was not the only thing on the govern-ment's mind during this time period. It was also concerned about the state of magazine publishing in the country. Yet another Royal Commission was charged with investigating the situation chaired by one of the government's most solid supporters, Senator Grattan O'Leary, an Ottawa-based newspaper publisher. O'Leary targeted what he felt was unfair competition in the magazine industry, in particular two journals, Time and Reader's Digest. Both magazines were owned and operated by American interests although they published a Canadian edition. Usually these editions were only a small part of the overall magazine. As a consequence, advertising rates for Canadian businesses were far lower than those of purely domestically produced. O'Leary wanted the government to remove the tax credits that Canadian advertisers received for expenses involved in placing ads in these journals. The outcry from Washington was predictable, but in 1976 the Liberal government enacted O'Leary's recommendations and eventually extended it to advertisers who used border television. Just before the turn of the century, Sports Illustrated successfully fought a government regulation to extend government support for the industry although the tax legislation remains intact, exempt for the time being under the cultural provisions of NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement). In 1998 the government passed Bill C55, which eliminated the discrimination against U.S. magazines publishing in Canada.

Although Canada has had a magazine industry since the Nova Scotia Magazine and Comprehensive Review of Literature and News first appeared in 1789, they have never played a significant financial role in the history of Canadian media. Most attempts to establish a magazine industry in the country during the period when newspapers were enjoying significant prosperity were inconsistent to say the least. Some such as J.S. Cunnabell's Acadian Magazine and Halifax Monthly Magazine did enjoy brief prosperity. By the mid point of the nineteenth century, Toronto had become the major magazine publication center in the country, but as in previous instances, most magazines, such as The Canadian Journal and the British Colonial, did not last very long.

The French language press did enjoy more success following Confederation. A Montréal publisher, Georges Edouard Desbarats launched his Canadian Illustrated News in December 1869, which he followed with a French language edition, L'Opinion Publique in 1870. In Toronto, a young artist with a political wit launched Grip magazine, a collection of cartoons and political satire which published for two decades. Both Queen's University and McGill launched successful academic journals during the second half of the nineteenth century. In 1887 Saturday Night, a collection of consumer news and pointed political coverage, first hit the newsstands of Toronto. The longest lasting and most stable of all Canadian periodicals, the Busy Man's Magazine, which eventually took the name of its founder, Maclean's—Le Magazine Ma-clean, was first published in 1896. Maclean's remains one of the country's largest publishers of trade periodicals in concert with its weekly newsmagazine. However, without government support, it is doubtful that Canada could support a magazine industry.

Government once more wielded its power in 1968. Dissatisfied with the performance of the Board of Broadcast Governors and recognizing that a new broadcasting environment was taking shape, the government again amended the Broadcasting Act. Faced with rising nationalism in Québec, it wanted the broadcasters to play a larger and more influential role in defining Canadian unity. One of the changes to the act was to charge the CBC primarily with this task. As well, the new act brought both cable casting and educational broadcasting under the jurisdiction of the new federal regulatory body, the Canadian Radio and Television Commission (CRTC).

One of the driving forces in the 1960s was the behavior of the private sector in the media. Like private entrepreneurs everywhere, the desire to expand and control lucrative markets became a cause in itself. Watching as one after another independent operator came under the umbrella of a major corporation, the government once again resorted to a commission of inquiry to investigate the potential problem. As always, it chose one of its own to head the investigation, Senator Keith Davey, known in Liberal Party circles as the Rainmaker. The 1970 report revealed much of what had been suspected about media economics and patterns of ownership. But the Davey inquiry did not stop at that point. It looked at the role of journalism in media, how journalists behaved, and how they were educated. Much to the chagrin of the owners, there were extensive comments on the workplace morale of many media workers.

One of the consequences of the Davey commission was the establishment of press councils across the country. Initially they emerged in Ontario, Québec and Alberta but soon thereafter spread across the country. Now they are almost an institutional way of life for most Canadian dailies and weeklies. Of these, the Ontario Press Council is the largest, with 226 members as of July 2001.

The councils attempt to mediate complaints about coverage when these are received. However, should a complaint go to a formal hearing, and should the newspaper lose the case, it must publish the results in a prominent place as soon as possible after a decision has been rendered to retain its membership.

In spite of what appears on the surface to be a relatively healthy newspaper market in Canada, serious concerns have been raised, as they have been elsewhere, about the diminishing number of corporations who now own the vast majority of the largest and most influential Canadian dailies. The situation has received the attention of the Federal Government on two occasions, once in 1970 when Liberal Senator Keith Davey was charged with investigating various aspects of the media situation in the country and again in the early 1980s when Thomas Kent chaired a commission investigating concentration of ownership in Canada's newspaper industries.

In 1980 two corporate giants, Thomson of Toronto and Southam of Hamilton, decided to reduce competition in their respective markets. Thomson closed the Ottawa Journal and Southam closed the Winnipeg Tribune. It was not lost on the government that these two owners actively competed with each other in both cities and that the closures were destined to ensure that no competition existed. As a consequence, the government chartered another Royal Commission, this one under former civil servant Tom Kent, to investigate the state of affairs in the industry. Overall, the Kent Commission felt that concentration of ownership was dangerous for the Canadian democracy and should be curbed. The industry did not agree and the Kent recommendations were denounced on virtually every editorial page in the country. The government retreated and did not implement any of the recommendations. Realizing the vulnerability of their respective positions, the industry now actively embraced the work of the press councils which they argued would provide meaningful checks on their more outrageous activities.

The issue emerged once again in 2002 when the Asper family of Winnipeg, owners of Can West Global Communications, announced that they would be centralizing editorial writing three days per week at the company's head office. The company had just finished the purchase of the Southam properties previously owned by Hollinger. The journalists rebelled by removing bylines, but the company stood fast to its premise that it had a right, if not an obligation, to promote its views in its newspapers. The senior executives at Southam reminded the journalists that it was they, and not the journalists, who owned the newspapers and thus had the power to make and enforce the decisions. As with the Can West Global situation, the newspaper industry in 2002 was in what could be described as its third consolidation phase.

In keeping with tradition practiced by previous governments, when the Conservatives, under the leadership of Brian Mulroney, came to power in 1984, yet one more Royal Commission was chartered to investigate broadcasting policy in Canada. It received its charge on April 9, 1985. The commission was jointly chaired by Gerald Caplan, a former national secretary of the New Democratic Party which sat in opposition to the ruling Conservatives and by Florian Sauveageau, a communications professor at Laval University in Québec City. They were given a wide mandate to investigate and make recommendations on the future of the Canadian broadcasting system. Suspicion ran high in public broadcasting circles that the Conservatives were about to use the investigation to either downgrade or destroy the CBC.

Once again, the investigation did not downplay the much-desired Canadian nationalist ideal. In fact, it reinforced the concept, although it dismissed the belief that the CBC should take the lead in promoting national unity. Instead, it argued that the CBC should focus on developing what it termed "a national consciousness." The commissioners also wanted to extend the concept of broadcasting to include other forms of media, namely provincial agencies, native groups, community groups, and those in minority languages and cultural communities. It saw these and other smaller groups as part of a larger public community. Although many of the recommendations were not formally acted on, the country now enjoys the presence of a national cable network operated by aboriginal peoples, multilingual radio and television services in most of the major cities and community programming aired through designated channels on cable television. The Broadcasting Act was finally amended, which removed the CBC from the business of promoting national unity. The Act did not, however, relieve the public broadcaster from the responsibility of generating part of its own operating revenue through the solicitation of advertising.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

As noted above, Canadian broadcasting policy has been driven since the arrival of radio by the concept that foreign intervention threatens the national identity, and that it is the responsibility of Canadian-owned and operated media to give access to Canadian creators and performers in order to offset the overwhelming influence of the American media in Canada. This is less of a problem in Québec, where the predominant language is French, though broadcasters there carry dubbed versions of the Ally McBeal and West Wing television shows. The Caplan Sauvageau Commission found that of the 52,000 yearly hours of broadcasting they investigated, only 370 were produced in Canada. Since 1986, the situation has changed significantly, with the CBC now boasting an all-Canadian prime time broadcast day. The recent inclusion of foreign specialty channels has once again brought the nationalist question to a head. Fundamentally, one thing has not changed since Caplan Sauvageau: the majority of major hits such as The West Wing dominate the top ten television shows in Canada on a weekly basis.

Although Canadian private broadcasters regularly espouse the virtues of a free market and a lack of regulation, they often turn to government for assistance in protecting their private spheres. Foreigners cannot own or control through proxy any Canadian broadcast media. On numerous occasions, the federal government has attempted to protect the Canadian magazine industry through tax protection or outright subsidy. Foreign booksellers are not allowed to set up competing shops in Canada. The Borders Books and Music chain was forbidden entry into the country to compete with a similar Canadian chain called Chapters. Eventually the person who attempted to bring Borders to Canada opted to begin her own chain, called Indigo. When Chapters fell on hard times, she merged the Indigo operation with Chapters. When Canadian press baron Conrad Black attempted to accept a seat in the British House of Lords, the Canadian government reminded him that he would have to relinquish his Canadian citizenship and consequently his newspaper chain. Black did for the most part cut ties to Canada, selling his principle holdings to broadcaster Can West Global.

Other than ownership requirements, the Canadian media industries are supported by government actions determined to either curb the influence of foreign media or to keep it out altogether. As noted earlier, the amendments to the Income Tax Act which removed the ability of Canadian advertisers to claim deductions for expenses made outside Canada is just one model. Another is the simultaneous substitution rule in cable that has caused friction between the Canadian and American governments since its implementation in the early 1970s. The policy was inspired to a significant degree by the first of a series of spectacular failures initiated by the CRTC, albeit unwittingly. In July 1972, it awarded a license to Global Communications for a regional television network to operate in southern Ontario. Global was to be an agency that purchased programming from independent producers in Canada, as opposed to producing the material themselves. The network came on the air in early 1974, but by the end of the spring, it was apparent that it was in serious difficulty and that its very survival was at stake. The CRTC, rather than let its prize project go down the drain, intervened.

Part of the bailout followed up on an experiment that had been tried earlier in Western Canada. It involved the removal of commercial messages from programs imported from the United States when they were being transmitted on cable. American broadcasters were not happy with this arrangement and did their best to make it difficult. Viewers soon caught on to something being wrong when they missed touchdowns on NFL games or returned to a program part way through an American commercial message. The Commission decided on the simultaneous substitution rule, aimed directly at U.S. broadcasters.

It works this way: when a Canadian broadcaster is carrying a U.S. program at the same time as the American network, Canadian cable operators can only carry the Canadian signal. As an example, when NBC broadcasts The West Wing , CTV broadcasts the program at the same time. Both Canadian and American audiences see the same show, but the Canadian audiences see commercial content produced and funded in Canada. And, since the U.S. signal is blocked on Canadian cable systems, any multinational advertiser must buy space on the Canadian program to reach a Canadian audience. In effect, artificially inflated ratings for these programs exist because there is no choice, and, as a consequence, advertisers pay higher prices for the advertising space. Canadian television programmers worked to ensure that any American product they purchased was shown at the same time as any one of the commercial networks in the United States.

News Agencies

Canada instituted telegraph service not long after Samuel Morse first demonstrated the viability of his invention. In the beginning, most of the telegraphs transmitted commercial messages, but to keep the operators occupied between messages, it was decided that they could use the service to send information to local newspapers. Eventually, telegraph companies bought rights of way along major railway lines. Noting the success of the business, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) decided to get into the news business. In 1894 it obtained a monopoly franchise to distribute Associated Press material in Canada. When the CPR attempted to double its price in 1907, a group of newspapermen in Winnipeg decided to set up the Western Associated Press in competition with the CPR. They challenged the railway's rate structure, won the battle and, in 1910, the railway got out of the news business entirely, selling its assets to the Western Associated Press. In cooperation with regional news sharing cooperatives in Central Canada and the Maritimes, a company called Canadian Press was born.

It was not until 1916 that a group of Canadian publishers reached agreement on how to fund and operate a national service. Part of the income for the new venture came from a $50,000 annual subsidy from the federal government. On September 1, 1917, Canadian Press opened an office in Toronto under general manager Charles Knowles, with a staff of 15 (Canadian Press employed a total of 72 staff across the country). For quite some time, Canadian Press was a non-profit cooperative news gathering agency designed to service only the newspaper industry. By the mid-1930s, the newly emerging radio industry began to discover the advantage of newscasting. In 1933, Canadian Press and the CBC signed a contract that bound the agency to write and air a 1,200-word newscast nightly on the network. It was the first step into broadcast for Canadian Press.

Canadian Press (CP) showed no interest in expanding its horizons in broadcast beyond the CBC. As a result, an American organization devoted to servicing only broadcasters signed up 25 Canadian stations when Associated Press refused to serve them. The agency, Transradio, operated out of a Toronto office. Another American agency, the United Press set up a Canadian broadcast subsidiary that is called British United Press in an aim to attract clients in Canada. In retaliation, Canadian press expanded its broadcast service to three, 1,000-word reports daily. In 1939 Canadian Press signed a deal with the CBC that gave it access to all of CP's content. In 1940 Transradio withdrew from Canada, and in 1941, the CBC founded its first, in-house broadcast news operation. Other than the CBC Radio and now television service, the only remaining broadcast news service in Canada is Broadcast News, an arm of Canadian Press. Although CP has been close to demise on a number of occasions due to battles among its members, it continues as the only major domestic agency to provide national and international news to Canadian media. Reuters also operates a small Canadian bureau, as does the French language service L'Agence France Presse, along with small and dedicated services such as the business service Canada News Wire.

Broadcast Media

As in most industrialized nations, the broadcast media are significant players. In Canada, there is a mixed private and public system. Until 1958, as noted above, the public Canadian Broadcasting Corporation dominated the system, owning stations, producing programs, and regulating the private sector. Private stations were allowed to exist, but in areas without CBC service, they were expected to broadcast a significant proportion of CBC programming. In many cases, this led to a great amount of duplication in the marketplace. Before CHCHTV in Hamilton, Ontario, became an independent in the early 1960s, it broadcast a full schedule of CBC programming, although it was only about 30 minutes away from the CBC production headquarters in Toronto. With the granting of licenses to private operators in 1960 and the subsequent birth of CTV, the Canadian Television Network, the pendulum swung toward the private sector. In the first years of the twenty-first century, Canada remained a nation with a mixed public and private system, although some levels of government have indicated that they wish to divest themselves of broadcasting responsibilities.

The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation operates four major television networks, two in English and two in French, in addition to a limited service covering the nation's Arctic regions. Two networks are targeted to mass audiences in both English and French Canada. Although the content is primarily produced in Canada by Canadians, these two networks differ little from any American commercial network in tone and appearance. To a significant degree, they are supported by advertising. Since the CBC receives an annual subsidy from the federal Parliament of $795 million out of a total budget of $1.32 billion, private broadcasters have often complained that the corporation is involved in unfair competition. The corporation's other two networks, News World in English and RDI in French, are cable channels. They are information channels with some similarities to CNN and they are supported by advertising to a significant degree.

Radio service in Canada reflects that of television. The CBC operates four radio networks, two in English and two in French. The primary networks are dedicated to extensive news, information, and current affairs coverage. Both stereo services are primarily in the business of programming music, with a classical music base and many live concerts. In the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, the CBC has abandoned a number of AM licenses to the private sector with the aim of converting most of its broadcasting service to FM. Together with the private sector, the CBC operates four specialty channels: Galaxie, a 30-channel continuous music broadcaster; ARTV, which focuses on arts; the Canadian Documentary Channel; and Country Canada. All of these are offered as subscriber operations. The CBC continues to sign affiliation agreements with private owners to broadcast CBC produced programming, especially on television. The CBC also operates Radio-Canada International, a short-wave service operated out of New Brunswick. It broadcasts in English, French, Spanish, Chinese, Arabic, Russian and Ukrainian. The service has faced closure on several occasions as CBC public funding fell.

The second most important segment of the public sector is provincial operations. There are six such operations, and one, ACCESS Alberta, is a hybrid: privately owned and operated with the bulk of its programming contracted to the provincial government. It operates both radio and television stations. The largest and most dominant of the educational networks operates in Ontario. It has both an English language service, TVOntario, and a French language service, Télévision Français d'Ontario (TFO). In some ways, programming resembles that of the American public television system (PBS), but there is a stronger reliance on locally produced programming. TVO and TFO are one of the largest producers of children's programming in both the English-and French-speaking worlds. For the most part, the system is funded by the government of Ontario. However, the system does have frequent membership fundraising drives. Along with TVO-TFO, educational television systems exist in Québec ( Télé-Québec ), in British Columbia (The Knowledge Network), the Maritime provinces (MITV), Alberta (ACCESS), and Saskatchewan (the Saskatchewan Community Network). As well as public television and radio, and educational channels, the Canadian legislatures operate channels to broadcast parliamentary proceedings and the Canadian version of C-Span, called C-PAC, can be found on cable systems across the country.

Much of the remainder of the radio and television system across the country can be found in corporate and private hands. The largest is BellGlobeMedia, owners of both the CTV Television Network and Canada's national newspaper the Globe and Mail. Until recently, the CTV network was owned by a cooperative operated by the CTV affiliates, each of whom owned the same amount of shares. As new stations began to join the system, individual share percentages dropped. As a consequence, an offer was made by Toronto's Baton Broadcasting, then owners of CFTO-TV, to purchase the majority shares. The CRTC approved the deal, and the cooperative ceased to exist. CTV is now free to make affiliation agreements with other privately held stations without surrendering share value. The other private, national network is operated by Can West Global Communications, which also is a major newspaper owner. Global began life as a regional, private network in 1972. After a bankruptcy scare, it changed hands several times until it was purchased by the Asper family of Winnipeg, the current owners.

The remainder of the Canadian media market is divided among several smaller players. The most significant player in this field is CHUM Limited of Toronto, which owns a number of radio and television stations across the country. Their most visible television presence is Much Music, the Canadian counterpart to MTV. Much Music operates three channels, one for everyday hits, one for older tunes and a new digital channel called Music Music Loud, created for heavy metal listeners. The owners of A-Channel, a western-based media family, were expanding into Ontario at the turn of the twenty-first century. They were granted a license to serve Toronto, with a new outlet planned for 2003. The emphasis of Corus Entertainment, an offshoot of the Shaw cable interests from Calgary, remains mainly in radio. Other players include Rogers Communications, the country's largest cable operator, who also owns television and radio stations as well as the Québec based Telemedia Corporation.

In Québec, the privately owned and operated counterpart to the English-language CTV is TVA, headquartered in Montréal. It has a smaller competitor, Télévision Quatre Saisons (Four Seasons Television), which has teetered on the brink of insolvency in the past.

At the turn of the twenty-first century, Canadian television had access to 82 specialty channels. Some, such as CBC News World and RDI, were part of the cable packages that both cable operators and satellite systems offered as part of their extended basic services. They were packaged with regular, off-air channels at a monthly fee. Others were packaged with U.S. superstations such as WGN Chicago or WSBK Boston as pay-TV channels. Recently, a new cast of digital channels became available, all of which are sold through separate subscription systems. Canadians wishing to access the most television channels can either subscribe to a cable service or opt for connection to a satellite system such as Direct TV or Star Choice.

The operating revenue for Canada's commercial television stations in 2000 was $1,887,221. Operating expenses amounted to $1,708,607, leaving an operating profit of $178,614. After corporate taxes were applied, this amount dropped to $105,225. The results do not include cable television operations, pay television, or any non-commercial endeavors.

Cable television has existed in Canada for a long time. It was begun in London, Ontario by Edward Jarmain when he decided a large receiving antenna on an elevated piece of land would vastly improve signals arrived in that city from the United States. London was geographically close to major U.S. cities, but not close enough to get reliable reception from the network stations that broadcast from those localities. In its early years, cable was promoted as a reliable way to receive interference free and reliable signals from distant stations. In Toronto in the mid-1960s, cable companies carried Buffalo's PBS station, WNED, in order to attract upper-income Ontarians to the systems. For some time, WNED could not be received off air in Toronto. Other cable companies in other communities also used similar techniques resulting in rapid cable growth. By 1975, six out of ten Canadians subscribed to a cable system. Provincial governments in Québec and the Prairies challenged federal jurisdiction over cable citing the fact that cable systems did not cross provincial boundaries and therefore should be provincially regulated. In 1977 the Supreme Court of Canada disagreed, and cable remained under federal jurisdiction.

Since the technology existed to import more and more distant channels, mainly from the United States, pressure was put on the CRTC to open more channels for this purpose. The commission was concerned that importing channels to areas where those channels were not licensed to serve would fragment the audience of Canadian-based stations and negatively impact their incomes. As a result, when cable companies asked the regulator to include some of these channels, they were often refused. For years, the Fox outlet in Buffalo, WUTV, was not allowed on Canadian cable systems in Ontario. This kind of scenario repeated itself many times across the country. Not only were cable companies subject to this kind of regulatory practice, they were also forced to set aside a channel for community programming which was intended to be advertiser free. There are now over two hundred of these operating in Canada with a variety of local programming, ranging from live sports, church services, bingo games, political talk shows, and interview programming to local documentary features. The cable industry also finances and operates the aforementioned CPAC, the Public Affairs Access Channel.

Cable came into its own in the early 1980s when the CRTC decided to license a number of channels with the express purpose of operating as cable-only channels. Initially, these channels were offered on a subscriber basis only, but eventually, most of the original cable-only services became part of cable's basic package. Throughout the remaining years of the twentieth century, cable operators added a number of new services, including movie channels, digital channels, and home shopping channels. Analog systems in Canada now regularly feature up to 78 channels consisting of everything from locally produced community shows, regular CBC, CTV and Global service and any one of a number of channels from outside Canada. Near the end of the 1990s, Rogers Cable in Toronto introduced a high-speed Internet service through its cable system. Other major players such as Shaw, Groupe Videotron, and Cogeco have followed. To accommodate the new services and in anticipation of local and long distance telephone licenses, cable companies in Canada launched an extensive capital investment into converting their service to wide band fiber optics cable.

At the turn of the century, the cable industry was faced with choosing a massive expansion strategy or merging with companies devoted to doing so. Revenues remained high for cable operators, coming in at $2,055,956. However, expenditures outstripped revenues, with a resultant overall loss of $192,666. The largest single expenditure was on technical services at $724,893. In all, Canadian systems operated 219,000 kilometers of line in the country.

Electronic News Media

By the late 1990s, virtually every major news medium in the country operated a web site. Only the smaller ones, such as Saskatchewan Community Television, did

Education & TRAINING

Until recently, communications and media studies have been in short supply in Canadian universities. For years, Canadian post-secondary education closely followed the British model, in which the arts, sciences, humanities and social sciences formed the core of the institution and were complemented by prestige professional