Costa Rica

Basic Data

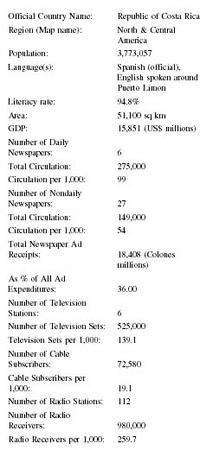

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Costa Rica |

| Region (Map name): | North & Central America |

| Population: | 3,773,057 |

| Language(s): | Spanish (official), English spoken around Puerto Limon |

| Literacy rate: | 94.8% |

| Area: | 51,100 sq km |

| GDP: | 15,851 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Daily Newspapers: | 6 |

| Total Circulation: | 275,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 99 |

| Number of Nondaily Newspapers: | 27 |

| Total Circulation: | 149,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 54 |

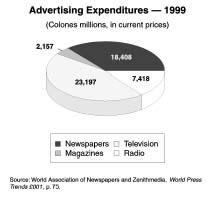

| Total Newspaper Ad Receipts: | 18,408 (Colones millions) |

| As % of All Ad Expenditures: | 36.00 |

| Number of Television Stations: | 6 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 525,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 139.1 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 72,580 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 19.1 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 112 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 980,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 259.7 |

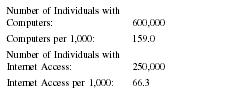

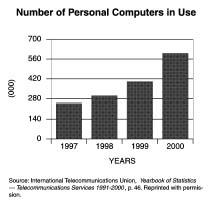

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 600,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 159.0 |

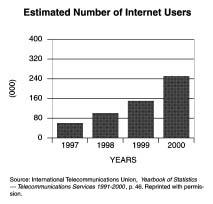

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 250,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 66.3 |

Background & General Characteristics

Costa Rica is a nation of 3.7 million people that boasts a long history of democracy, no army, and relatively peaceful political development, which is in stark contrast with the war-torn legacies of most of its Central American neighbors. Long thought a stellar democracy wherein the press basked in unlimited freedom, the murder of a popular radio journalist in 2001 revealed a darker side to the country that has often been referred to as the Switzerland of Central America.

Costa Rica covers 51,000 square kilometers and is divided into seven provinces. The nation's capital, San José, is home to one-third of all Costa Ricans. The vast majority, 97 percent, of Costa Ricans are of European or mestizo (mixed European and Native American) descent, although a growing number of immigrants from neighboring Nicaragua are slowly beginning to transform the nation's homogenous demographics. Roman Catholicism is the dominant religion but evangelical Protestantism is growing at a rapid pace. In San José, the number of evangelicals doubled in the 1980s and it is estimated that by 2010, 20 percent of the population will be Protestant.

In July 2001 the murder of the popular radio journalist, Parmenio Medina, shocked the nation. Medina was murdered the night he was to receive an award from a Costa Rican nonprofit organization for defending freedom of expression. He was shot three times at close range and died on the way to the hospital. Medina, Colombian by birth, was well known for his 28-year-old radio program, La Patada (A Kick in the Pants) that often denounced official corruption. Medina's muckraking approach to journalism left him with many potential enemies. He had recently aired accusations about alleged fiscal improprieties at a local Catholic radio station, Radio María. His reporting led to the station's closure and an investigation into the actions of its former director. Some believed that Medina could have been killed for investigating money-laundering activities by a large drug-smuggling cartel. A year after his murder no one has yet been brought to trial although national TV and newspapers have reported that four members of a criminal gang are suspected of having been paid to assassinate Medina.

A survey taken by the nation's leading newspaper, La Nación a month before Medina's murder, found that 55 percent of the 97 journalists polled said they had received some kind of threat during their careers. Though some threats were physical, most journalists were threatened with defamation suits. Some journalists have said that they are reluctant to investigate important cases, such as Medina's murder, because Costa Rica has a harsh penal code that could lead to imprisonment or heavy fines.

These recent events are a strict departure from the typical belief that Costa Rica is an oasis of peace and stability in the historically war-torn and impoverished region of Central America. Latin America's longest-standing democracy, Costa Rica is more known for its eco-tourism trips, as a U.S. retirement community, and the Nobel Peace Prize-winning former president, Oscar Arias, than for political violence. The nation has had little violence despite its proximity to Guatemala, El Salvador, and Nicaragua, all countries that suffered from devastating civil wars in the 1980s. Costa Rica has one of the highest literacy rates in the region with 95 percent of the adult population considered to be literate. Indeed, Costa Rica has a historical precedent for supporting education, beginning universal free public education in 1879. It has the region's highest standard of living, and a life expectancy comparable to that of the United States. In general, an educated public with higher per capita average than the region's norm at US$3,960 has enabled the rapid development and expansion of all forms of media.

Although Columbus stopped over briefly on Costa Rica's Caribbean coast in 1502, for most of the colonial era, Costa Rica remained a forgotten backwater since it had little that the Spanish colonialists were looking for, namely, a significant labor supply and/or mineral wealth. An isolated and neglected province of the kingdom of Guatemala, Costa Rica did not have much in the way of publishing. Guatemala was the center of publishing for two hundred years having had its first press installed there in 1641.

In 1824 an elected congress chose Juan Mora Fernandez as the first chief of state. The first newspaper appeared shortly after his re-election in 1829 although a local citizen had to subsidize the purchase of an English printing press. The first regular weekly newspaper, Noticioso Universal, was issued on January 4, 1833. Noticioso Universal closed after two years because the early development of the press in Costa Rica had three strikes against it: there was not a sufficient literate and economically viable audience to sustain a local newspaper; the weekly in existence had to compete with the more established newspapers arriving from Guatemala and South America; and finally, there was little available and affordable paper on which to print the news. Between 1833 and 1860, ten different newspapers existed in Costa Rica, none of them lasting for more than two years. The government began operating its own press in 1837, primarily printing decrees, orders, and laws.

It was not until the introduction of coffee in 1808 that Costa Rica began to attract a significant population. Coffee brought wealth, a class structure, and linked the nation to the world economic system. The coffee barons, whose growing prosperity led to rivalries between the wealthiest family factions, vied with each other for political dominance. In 1849, members of the coffee industry elite conspired to overthrow the country's first president, José María Castro, who had established a newspaper and a university. The President believed that ignorance was the root of all evil and that freedom of the press was a sacred right. Unfortunately, Castro's rule was interrupted by William Walker, the U.S. citizen who believed in the manifest destiny of the United States to rule other peoples. Walker already controlled Nicaragua in 1855 and he invaded Costa Rica the following year. His unintended role in Costa Rican history was to help unite its people, who roundly ousted him the same year.

During the 1880s the national leadership was under the helm of the liberal elite who stressed the values of the enlightenment, although charismatic leaders often held sway over political ideologies and programs. The free press, however, increasingly guided public opinion, and Costa Ricans became accustomed to hearing critical discussions of ideas as well as the ideas of political candidates. Yet political rivalries often resulted in moments where the press was repressed. For example, in 1889 the new president Jose Joaquin Rodriguez, caught between the country's liberal and conservative factions, suspended civil liberties, including the closure of opposition papers. He dissolved congress in 1892 and imprisoned a number of journalists. Rafael Iglesias, Rodriguez's successor, did much to beautify the capital, but he also declared that the violently critical newspapers had turned his people against him and he clamped down on the press, even going so far as to flog some of his detractors publicly. During the first century of the country's independence, the freedom and the power of the press was seen as a double-edged sword by many of the nation's leaders. In this context, in 1902 one of the nation's longest lasting press laws was established which protected the "honor" of individuals from being attacked in the press.

The intertwined role of the media and politics is a strong theme in recent Costa Rican history. For example, a 1942 speech broadcast on radio by future president, José Figueres, against the communist-affiliated president, Rafael Calderón, proved to be pivotal to the latter's political demise. The press was generally critical of Calderón's

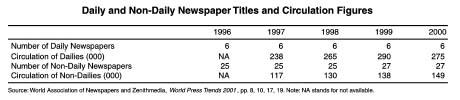

Costa Rica has six daily newspapers nationwide. The total circulation is 88 papers per one thousand inhabitants. The largest newspaper, La Nación, was started in 1946 and represented the commercial interests of the business elite. La Nación was close to the Nicaraguan Contras and served as a voice for their cause during the U.S.-backed Contra-Sandinista war of the 1980s. La Nación distributed a weekly supplement called Nicaragua Hoy, directed from Miami, Florida, by Pedro Joaquín Chamorro, son of the murdered editor of the Nicaraguan daily, La Prensa.La Nación also publishes a number of magazines including Perfil, Rumbo, and Ancora. The paper had a circulation of 110,000 in 1997.

The nation's two other dailies, La Prensa Libre and La República share the conservative tendencies of La Nación. Both newspapers were originally seen as alternatives to the nation's premiere daily, but both have moved to the right since their founding. The morning paper, La República was founded in the 1950s and was sympathetic to President Figueres, and for years represented a true counterpart to the ideological stance of La Nación. In the mid-1990s it had a circulation of 55,000 and is known for being only slightly less conservative than La Nación.La Prensa Libre is an afternoon paper with a circulation of about 45,000. It was founded in the 1960s. One of the only newspapers to originate outside of San José is El Sol de Osa, a general interest newspaper published in Puerto Jimenez.

Some smaller papers offer a more liberal view but their influence is limited by their relatively small circulation. Semanario Universidad, is the official paper of the University of Costa Rica and it has gained an international reputation for its coverage of politics and the arts. It is characterized by a leftist editorial perspective. In late 1988 the newsweekly Esta Semana appeared. All of these publications originate in San José, Costa Rica's capital. A number of supplements are published on a weekly basis. These include Sunday's Revista Dominical, an events showcase with interviews of local personalities. An educational supplement Zurqui appears on Wednesdays and targets a younger audience; on Thursdays two other supplements appear. En forma (In Shape) reports on health and wellness issues; and Tiempo libre (Free Time) lists the calendar of social events in the capital. Other daily newspapers include El Heraldo and Extra.

The nation's primary English language newspaper, the Tico Times, was founded by Elisabeth Dyer in 1956. According to the paper's first editorial, it was "begun in order that young people interested in journalism could receive practical, on the job training, and in so doing to provide the English speaking public of Costa Rica with a newspaper of special interest to the American and British colonies and Costa Ricans who know, or are learning, English." For its first four years, the Times was a volunteer effort, produced by members of the English-speaking community, including high school students. The paper's circulation has grown to 14,500 and is printed in Costa Rica and California and distributed free. The paper remains a training ground for journalists and for those who want work experience in Latin America, and many of its former volunteers have gone on to influential media positions in the United States and Europe.

By 1980, the Times was respected internationally for its investigative journalism and its coverage of Central America, especially of the Nicaraguan revolution and the Iran-Contra affair. The Times' reporter Linda Frazier was among those killed in the May 1984 bombing of the Nicaraguan contra leader Edén Pastora's press conference on the Nicaraguan border and the paper campaigned vigorously to expose the truth behind the bombing. With civil unrest diminishing in Central America the paper's special interests have centered on tourism and environmental concerns, at times an uneasy balance, as much of the paper's advertising revenue is from real estate developers.

Costa Rica's relative prosperity in Latin America provides a large and literate audience to sustain a number of magazines, whose topics range from glossy tourism monthlies, to evangelical Christian publications, to conservation issues. Eco-tourism publications have acquired a growing number of international subscribers. Gente 10, a magazine that targets a gay and lesbian audience, was founded in 1995. Scholarly journals are also published, including Káñnina (past tense of "to dawn" in the indigenous Bribrí language) published by the University of Costa Rica, which showcases scholarship in fine arts, the humanities, and the social sciences.

San José has long dominated Costa Rican society and the vast majority of the nation's publications originate there. Radio, however, is more important than daily newspapers outside of the nation's capital as the primary way in which people receive information. All of the newspapers follow the tabloid-sized format.

Economic Framework

Costa Rica's economy is based primarily on agriculture, light industry, and tourism. Traditionally considered to the strongest economy in Central America, Costa Rica's gross domestic product in 2001 grew only 0.3 percent and inflation stood at around 11 percent, triggered by low world coffee prices. The last 20 years have seen Costa Rica move away from its social welfare past and into the free market reforms of present-day Latin America. The nation has also faced economic crises and increasing distance between the social classes. In the mid-1980s, for example, the top 10 percent of society received 37 percent of the wealth while the bottom 10 percent had 1.5 percent. Costa Rica became the first underdeveloped country to suspend debt payments in 1981. The worst of the crisis was over by 2002, but the nation continued its "structural adjustments." From 1982 to 1990 the U.S. Agency for International Development gave over 1.3 billion U.S. dollars to Costa Rica. The foreign aid and economic recovery came with the imposition of harsh austerity measures, a restructuring of financial priorities, and a revamped development model.

The last four presidents, despite coming from two different political parties, have followed the same path of economic liberalism, stressing free trade, export promotion, and less money for the public sector. Hurricanes have also damaged the economy in recent years beginning with César in July 1996 that caused several dozen deaths and cut off much of southern Costa Rica from the rest of the country. The Inter-American Highway was closed for about two months and the overall damage was

The majority of the media in Costa Rica is privately owned and there are a few media conglomerates that own the majority of the media in the entire nation. La Nación stockholders also hold interests in the daily paper, La República, as well as the popular radio stations, Radio Monumental and Radio Mil. The owners of the major media tend toward conservative politics and their power as media owners allows the news to lean to the conservative side of issues.

In the 1980s there was a good deal of concern that the ownership of the media in Costa Rica might have a tendency to deliver politically-biased news accounts. The discussion was brought to the forefront as the nearby war between the U.S.-backed Contras and the Marxist-inspired Sandinistas escalated in Nicaragua. Four of the five privately owned major TV stations broadcast a barrage of sensationalized news reports warning of the sandino-comunista threat. Analysis of news coverage in the 1980s found that national stations rarely ever interviewed Nicaraguan officials yet they gave considerable coverage to the Reagan administration's viewpoint. Former Nicaraguan contra leader Edgar Chamorro also testified in the World Court that CIA money was used to bribe journalists and broadcasters in both Costa Rica and Honduras.

Many journalists in Costa Rica argue that the media owners and the media in general are considerably to the right of the general population, but that alternative media has not been able to develop because of the conglomerate nature of the media. One journalist who tried to start up an alternative newspaper, commented that his efforts were hampered since media and business owners were "one and the same."

Press Laws

While the constitution provides for freedom of speech and the press, and the government largely respects these rights, a number of outmoded press laws have caused controversy as well as internal and international pressure for reform. In 1999, President Miguel Angel Rodríguez presented a bill to congress that attempted to make improvements in press legislation. Specifically, it proposed the abolishment of Article 7 of the old Press Law from 1902 which makes publishers liable for offences by third persons in their news outlets. It would also increase to 15 days the time allowed to respond to a lawsuit and include a provision that exempts from responsibility those who have only provided the material means for publication or sale of slanderous, libelous or defamatory reports. The proposed changes also pushed for removing the burden of proof from the journalists to demonstrate that their published information is true.

In 2001 the murder of Parmenio Medina re-focused attention on the need to revamp the nation's antiquated press laws. But this was not the only event to spur legislative change since a few months before his murder, the Inter-American Press Association (IAPA) analyzed the Costa Rican constitution in light of the Chapultepec Declaration of 1994 (also known as the Declaration of Free Speech for the Western Hemisphere) and found that four of the ten points recommended for guaranteeing freedom of the press were absent in Costa Rica. In effect, IAPA found that there was insufficient legal support for journalists to protect their sources, harsh repercussions for journalists who criticized public officials, restrictions on the free flow of information and censorship.

The most controversial aspect of Costa Rican legislation has been the long-standing desacato or "insult" law which protects public figures from critical journalists. The Legislative Assembly voted on March 26, 2002 to eliminate Article 309 of the Criminal Code which made it a crime to "insult" the dignity of the president and other public officials. This aligns the code with the "actual malice" standard, first articulated by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1964. This standard requires plaintiffs to prove not only that published information about them is false, but also that the journalists knew or should have known it was false at the time of publication. Until the change in this law, journalists faced potential jail sentences of anywhere from a month to two years in prison, or as much as three years in prison if the offended party is a higher-ranking official such as the President.

The legislation also contains a neutral reporting standard, which says that journalists cannot be sued for accurately reproducing information from an explicitly mentioned source. For years, the international and local press communities and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights had urged elimination of "insult" laws. The elimination of the law suggests greater press freedom will follow since journalists are no longer threatened with jail time for reporting on political or powerful personages in a less than flattering manner.

The World Free Press Committee (WFPC) is still pushing for the following changes in the Costa Rican legal code:

- Article 149, which establishes the "evidence of truth" ( prueba de la verdad ) as a necessary standard for journalists to prove. The WFPC recommends that the article should be revised to bring it into conformity with press freedom principles.

- Article 151, which as it currently stands establishes some "exclusions" of responsibilities to people who have been accused. Reform would increase the number of such exclusions.

- Article 152, which as it stands is most restrictive, penalizes the "reproduction of offenses." The WFPC suggest introducing instead the principle of "faithful reproduction," which is recognized by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

Although the desacato law had been invoked infrequently, journalists say its existence had a chilling effect on news reporting. In 2001 another San José criminal court ordered Rogelio Benavides, editor of La Nación's TV supplement Teleguía, to pay a fine equivalent to 20 days' wages or face a jail sentence. Enrique González Jiménez, a beauty pageant promoter, sued Benavides based on a review of the pageant that appeared in a 1999 issue of Teleguía (TV Guide). While article 151 of the Penal Code holds that press reviews cannot be characterized as "offenses against honor" the court nonetheless convicted Benavides of libel and ordered that its ruling be published in Teleguía.

While welcoming repeal of the desacato law, many Costa Rican journalists say it is a minor obstacle to press freedom in Costa Rica. There is concern that repeal will lead lawmakers to claim that enough was done toward reform, and that officials will fail to act on the nation's far more troublesome and complex libel, slander, and defamation laws. Unlike those in most other democracies, Costa Rica's defamation laws are criminal, rather than civil statutes. This means that journalists can receive prison sentences and heavy monetary fines for convictions.

While not common, these statutes have been employed far more often than journalists would like. Up until the repeal of the desacato law, news media in Costa Rica had more than a dozen criminal defamation actions pending, with penalties totaling thousands of dollars. In June 2001, for example, the Costa Rican Supreme Court upheld a libel verdict against three journalists from La Nación. The case stemmed from a 1997 article reporting that a former justice minister had been accused of appropriating state-owned weapons and an official car for his personal use. The politician was awarded damages of US$34,000. The decision also required that La Nación publish the first seven pages of the decision in their entirety. One of the arguments used to justify such a large fine was that the articles were available on the Internet, and therefore reached a larger audience for a longer period of time. The court also ordered La Nación to remove all links from its web site that could lead the reader to the contested articles. The judges ruled that the journalist had shown malicious intent by continuing to investigate the case despite testimony from two former Costa Rican presidents who vouched for the politician's integrity.

Other problematic legislation includes the "right of response" law passed by congress in 1996. This law provides persons criticized in the media with an opportunity to reply with equal attention and at equal length. While the print and electronic media continued to criticize public figures, the law has proven difficult for media managers to administer. On occasion, some media outlets delayed printing responses because submissions were not clearly identified as replies to previously published items.

Costa Rica's government has also tried to foster political tolerance and dialogue through laws like the one that requires broadcasters to accept political ads during campaign periods. During the highly charged political climate of the 1980s, Costa Rica managed to maintain its democratic political tradition during the presidential campaign. With a battle raging in bordering Nicaragua, Costa Rica's right-wing candidate Rafael Angel Calderón Fournier, a godson of former Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza García, was shown talking one-on-one with Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, and Pope John Paul II in televised advertisements. His opponent, Oscar Arias Sánchez, brought in liberal American consultants, who used polling to identify what was worrying the large bloc of undecided voters and refocus the campaign appropriately. By promising jobs, housing, and peace, Arias was able to overcome Calderón's wide lead in early polls to win the presidency in February. The fact that Arias was allowed to advertise on television indicates that the Costa Rican media carry a wider range of views than those of less democratic countries. There have been times, however, when there have been unconfirmed allegations that the government withheld advertising from some publications in order to influence or limit reporting.

Censorship

While little outright censorship exists, reports that journalists and editors are forced to monitor what they write and publish have been increasingly frequent. Editors say they censor themselves and their reporters routinely, for fear of incurring penalties that could mean imprisonment, loss of their jobs, or corporate bankruptcy. A survey done by La Nación which asked journalists a number of questions about their profession showed that many of them practiced some sort of self-censorship. Limiting access to information can be seen as a subtle form of information control and a number of journalists complained that public officials were not forthcoming in this regard. For example, a majority of the journalists interviewed said that while they had direct access to public officials, there were many ways in which these sources avoided their attempts to interview them. Often, it was difficult for journalists to make it through the "screen" of intermediaries (press secretaries, secretaries, assistants, and others). If an interview was obtained journalists complained that public officials pled ignorance or claimed confidentiality agreements prohibited an answer.

State-Press Relations

As mentioned before, many of the laws governing the press in Costa Rica have been designed to protect the honor of public officials, complicating the relationship between the state and the press. The ability of the press to be critical of the state without repercussions is not secure. The strict libel laws, for example, resulted in the firing of two reporters who investigated fraudulent business deals related to PLN President-elect José María Figueres in 1993: one reporter from Channel 7 was reportedly dismissed from her job because of pressure from the PLN after she reported on private sector corruption; a reporter from La República said that he had left his editorial position because of alleged pressure from officials close to the President-elect. The reporter had been working on several articles that linked Figueres to alleged fraudulent mining deals.

In 1995 the Tico Times reported that the popular television program, "Diagnóstico" had been cancelled by the government-run National Radio and Television System (SINART). Critics of the decision to cancel the program, which aired weekly on Channel 13 and had been running for 10 years, alleged that it was one of the few shows where guests felt free to discuss a number of important issues in Costa Rica. The show's host, a politician named Alvaro Montero, referred to it as the most liberal program in the country and said that he had to struggle for years to keep it on the air. According to the Tico Times, the administration of President Rafael Angel Calderón Jr. first tried to shut down the program by terminating an airing in mid show. The Figueres administration SINART officials reportedly tried to end the program by cutting off its funding. Montero financed the show out of his own pocket for two years. The government claimed the show was cancelled out of a conflict of interest given that Montero was a potential candidate for president in the 2002 elections.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

The nation's democratic political structure, tourism industry, and large retirement community from the United States make it very receptive to foreign media. The international station, Radio For Peace International (RFPI), has studios and transmitters located in El Rodeo, Costa Rica, and with the revocation of the colegio law in 1995, there are no longer any restrictions on foreign journalists working in Costa Rica. The end of civil wars in Central America has also made the entire region safer for foreign journalists reporting there.

Until 1994 there were legal limits to the ownership of national media by foreigners. After the government revoked this law, it opened up the way for the Hollinger group, headquartered in Canada, to buy the newspaper La República. Foreign ownership, however, is subject to a number of bureaucratic constraints.

With the advent of cable, satellite dishes, and the Internet, foreign media entered Costa Rican society with substantial force over the last two decades of the twentieth century. Foreign-funded periodicals have left their imprint on Costa Rican media. Primarily sponsored by aide organizations, such publications have made an important contribution to the dissemination of information. The merging of local and foreign media is representative of many joint ventures here. For example, in 1994 an international council began funding a far-reaching demographic analysis of Costa Rican society and the resulting publication appears annually as Estado de la Nación (State of the Nation) and appears on the Internet. Costa Ricans watch Venezuelan and Mexican soap operas, soccer matches, and dubbed U.S. programs on commercial channels. Despite a law limiting imported programs to 75 percent of broadcast schedules, about 90 percent are imports. In addition, U.S. programs dominate the cable channel offerings in parts of the capital, San José.

News Agencies

There are a number of news services that operate in Costa Rica. These include Agence France Presse, Telenoticias, Rainforest Alliance, Diario La Nación, and the Tico Times. The Internet also provides rapid information access to news desks.

Broadcast Media

Radio is extremely popular in Costa Rica and is especially important for those Ticos who live outside of the capital city. In 2002 about 130 radio stations existed. Daily radio programming included talk shows and soap operas, political and social commentary, educational and religious programming, and sports coverage. Until Medina's murder, La Patada was one of the most popular radio programs in Costa Rica. It generally provided a light-hearted perspective on the news mixed with humor and political criticism. Another show, La Opinion , offers serious news commentary and is broadcast on Radio Reloj.

Evangelical Christian stations have blossomed since the 1980s. American missionaries were the first to broadcast the Protestant message by radio and television. The radio station Faro del Caribe, for example, has been broadcasting since the 1940s and includes programs targeted for the instruction and entertainment of children, mothers, and young people through Bible study, radio theater, advice, and music. Radio programming has also fulfilled other goals. In 1993 the government established the Costa Rican Institute of Radio Education in an effort to provide access to education to residents in rural areas. Programs such as "The Teacher in Your House" are broadcast from 12 noncommercial stations and complement correspondence courses in public schools. Lessons in English are also immensely popular.

Of the many radio stations in Costa Rica, Radio Reloj has the most listeners and it is also fairly conservative in nature. The news station Radio Monumental is also quite conservative and reflects the right-leaning opinions of its owners. Many radio stations carry Voice of America (VOA) and other U.S. Information Service programs including Radio Costa Rica which devotes about half its broadcast time to VOA programming. VOA's "Buenos Dias, America" feeds to 28 radio stations in Costa Rica. The most liberal station currently broadcasting is Radio America Latina which has proved responsive to the concerns of the popular movement.

Costa Rican television transmission began in the 1950s and today there are a dozen commercial stations and one government-run station. The most viewed stations are Channel 4 Multimedia, Channels 6 and 9 Repretel, Channel 7 Teletica, and Channel 2 Univisión. The Picado family owns the cable network, Cable Tica, and Channel 7. Angel Gonzalez, who is based in Florida, partially backs Channels 4 and 9. The other channels are privately owned with the exception of the national television network which is publicly owned and SINART (Channel 13), a government-controlled cultural channel.

Over 90 percent of Costa Rican households have at least one television set. Cablecolor, the local cable service, broadcasts the U.S. government's daily program as well as CNN's 24-hour news service. Channel 7 leads the others in terms of viewers, and is trying to assert full control of the medium through the professionalization of its "Telenoticias" news program. Channel 7, formerly owned by ABC, is of the same ideological stripe as the major print media. Channel 4 has gained in popularity over the last few years, perhaps due to offering a left-leaning political perspective, and hence, a contrast to the majority of Costa Rican media. A public station founded by the PLN during a previous period in power, Channel 13 offers a more liberal take on current events and offers a wide array of cultural programming. Costa Rican television also broadcasts programs from the rest of Latin America.

There has been little interference with the operation of television stations, with some exceptions. A Costa Rican court decision made in 2001 required a privately owned station to invite all 13 presidential candidates to appear, rather than just the frontrunners. The Inter-American Press Association called the court order a "fla-grant interference in the news media's editorial and journalistic independence." The order was issued by a majority of justices of the Costa Rica Supreme Electoral Tribunal, upholding a request for injunction filed by three minority political party candidates to the Costa Rican presidency who had not been invited to take part in a debate scheduled to be aired by the privately-owned Channel 7 TV. The station only invited the four leading candidates, who between them were estimated to account for 95 percent of the public vote.

Electronic News Media

By 2000 about 150,000 people in Costa Rica, or 3.9 percent of the population, were Internet users, accessing it through either one legal or two illegal Internet service providers. Most of the important newspapers also have an online presence, as do many of the national magazines.

La Nación publishes an online summary of news events in English and has news archived since 1995. AM Costa Rica is a website updated Monday through Friday targeting the English-speaking retired community in

The following newspapers and magazines have web-sites:

- La Nación: www.lanacion.co.cr

- La República: www.larepublica.co.cr

- Tico Times: http://www.ticotimes.co.cr

- AM Costa Rica: http://www.amcostarica.com

- Diario Extra: http://www.diarioextra.com

- El Heraldo: http://www.elheraldo.net

- La Prensa Libre: http://www.laprensalibre.co.cr

These radio stations are broadcast over the Internet:

- Radio Columbia (primarily sports coverage): http://www.columbia.co.cr

- Radio Monumental: http://www.monumental.co.cr

- Radio Reloj: http://www.rpreloj.co.cr

Education & TRAINING

To professionalize its media Costa Rica passed a law in 1969 that required national news reporters to graduate from the University of Costa Rica's journalism school ( colegio de periodismo ). The so-called colegio law has been controversial almost from the outset since it acts, at times, as a restrictive licensing measure. Furthermore, during the first few years after the law's inception, the University of Costa Rica did not have a journalism program in operation making the law impossible to uphold. As a result, journalists were allowed to be members of the colegio if they had at least five years of consecutive journalistic experience or ten years intermittent experience.

The colegio system has been controversial throughout Latin America since it has been interpreted as a professional licensing board that can curtail the freedom of individual journalists to exercise their profession. In 2001 La Nación published an article detailing the history of the colegio and its many failures to support journalists over the last 25 years. Most of the charges included instances of aggression against the press when the colegio failed to back individual journalists, radio and television stations, and newspapers, motivated by the licensing board members' conservative political alliances with the national government.

In 1994 the colegio began lobbying for passage of a constitutional amendment to permanently ensure its ability to define who exercises journalism in the country. The amendment would have protected the colegio from international criticism such as that issued by the inter-American Human Rights Court which ruled the licensing practice a violation of press freedom. Colegio leadership argues that the body serves to create professional standards, minimize cultural imperials and protect journalists' rights. The colegio has a code of ethics with 17 articles that was approved by the organization's general assembly in October 1991.

The Tico Times successfully took a case to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights over a Costa Rican law requiring the licensing of journalists. The Times claimed harassment by the colegio for over 20 years even though the colegio admitted it was unable to supply enough qualified journalists. In 1995, the Costa Rican Supreme Court addressed the problems inherent to the colegio system and declared the licensing of journalists unconstitutional. This was seen as a major victory for advancing legislative support of freedom of expression in the country.

Journalism degrees are awarded by the University of Costa Rica and the Latin University of Costa Rica. In addition a number of organizations sponsor seminars and conferences related to the practice of journalism. Costa Rica is one of the most popular spots for international journalistic conferences dealing with Latin America. The International Center for Journalists sponsored seminars on the media and freedom of expression in the Americas in Costa Rica. The Costa Rican colegio also organized conferences and workshops on social communication, human rights and the media, taking place frequently in San José. The city often hosts special courses to train media specialists in radio and television. A radio station from the Netherlands, Radio Hilversum, held a series of such workshops in San José open to all Latin American and Caribbean journalists. The World Bank Institute's Governance and Finance Unit and Radio Nederland Training Center, located in Costa Rica, also organized a course in investigative journalism conducted over the Internet.

Summary

The Costa Rican mass communications industry can support both pessimistic and optimistic predictions. For the pessimist, it is easy to point out that a popular muck-raking journalist was killed in cold-blood and that his attackers have yet to be officially identified or tried. Costa Rica's press freedom and development is also limited by the concentration of the media in the hands of a powerful few, and an increase in U.S. influence in the country, both economically and also culturally. For the optimist, the openness with which La Nación conducts and publishes interviews with journalists about their profession suggests that there is indeed a greater level of freedom of expression than one would imagine given the survey's critical findings. Also, during most of the 1990s, the media in Costa Rica was becoming more aggressive in its interrogation of government officials suspected of incompetence, corruption, and influence peddling. In addition, the repeal of the colegio law in 1995 and the recent repeal of the "insult" law also suggests that the protection of the rights of journalists to practice their profession without the fear of being fined, imprisoned, or expelled is being institutionalized.

Historically, the nation's emphasis on both education and freedom of the press have resulted in a great resistance to any attempt to restrict these rights and even greater resilience to bounce back quickly from those moments when such rights have been constrained. Medina's murder has resulted in greater discussion about freedom of the press and changes to provide the legislative teeth to ensure those freedoms. The nation's literacy rate, the public's increasing access to the Internet, and the rich opportunities for journalists and other media professionals to receive on-going training, suggests that the press in Costa Rica will endure.

Significant Dates

- 1995: Costa Rican Supreme Court issues a decision saying that the licensing of journalists was unconstitutional.

- 1996: Legislative Assembly passes "right of response" law which provides persons criticized in the media with an opportunity to reply with equal attention and at equal length. The law has proven difficult to enforce and administer.

- 1999: President Miguel Angel Rodríguez proposed a bill to the Costa Rican legislature, the Law to Protect Press Freedom, intended to make important improvements in press legislation.

- 2001: Popular radio journalist Parmenio Medina was murdered in what is assumed to have been retaliation for Medina's investigative journalism. No one had been arrested for his murder as of 2002. The tragedy sent shockwaves through the nation and spurred on legislative attempts to update outmoded legislation.

Bibliography

Alemán, Eduardo, Ortega, José Guadalupe, and Wilkie, James W., eds. Statistical Abstract of Latin America. Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center Publications, 2001.

Attacks on the Press: A Worldwide Survey. New York: Committee to Protect Journalists, 1994.

Baldivia, Hernán, ed. La formación de los periodistas en América Latina: México, Chile, Costa Rica. México D.F.: CEESTEM, 1981.

Biesanz, Mavis Hiltunen, Biesanz, Richard and Biesanz, Karen Zubris. The Ticos: Culture and Social Change in Costa Rica. Boulder and London: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1999.

Borders Without Frontiers , Costa Rica Annual Report 2002.

Helmuth, Chalene. Culture and Customs of Costa Rica. Westport, CT and London: Greenwood Press, 2000.

IPI Report, The International Journalism Magazine (November/December 1995).

Lara, Silvia, with Barry, Tom, and Simonson, Peter. Inside Costa Rica: The Essential Guide to its Politics, Economy, Society, and Environment. Albuquerque, New Mexico: Resource Center Press, 1995.

Marshall, Oliver. The English-Language Press in Latin America. London: Institute of Latin American Studies, University of London, 1997.

Martínez, Reynaldo. "Sociedad Interamericana de Prensa (SIP) considera que en nuestro país se violentan cuatro principios que garantizan este derecho." La República, July 2, 2001.

Skidmore, Thomas E. and Smith, Peter H. Modern Latin America. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Solano Carboni, Montserrat. "The Silence: A Year Later the Murder of a Popular Costa Rican Journalist Remains Unsolved." New York: Committee to Protect Journalists, July 2, 2002.

Uribe, Hernán O. Ética Periodística en América Latina: Deontología y estatuto professional. México D.F.: Universidad Naciónal Autónoma de México, 1984.

Vega Jiménez, Patricia. De la Imprenta al Periodico: Los inicios de la comunicación impresa en Costa Rica 1821-1850. San José, Costa Rica: Editorial Porvenir, 1995.

World Press Freedom Review, 2000.

Kristen McCleary