Guatemala

Basic Data

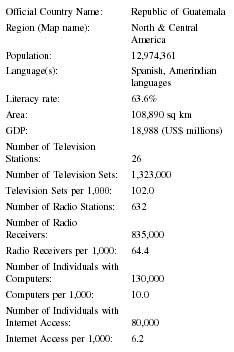

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Guatemala |

| Region (Map name): | North & Central America |

| Population: | 12,974,361 |

| Language(s): | Spanish, Amerindian languages |

| Literacy rate: | 63.6% |

| Area: | 108,890 sq km |

| GDP: | 18,988 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Television Stations: | 26 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 1,323,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 102.0 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 632 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 835,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 64.4 |

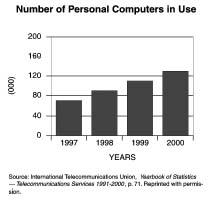

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 130,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 10.0 |

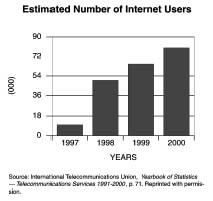

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 80,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 6.2 |

Background & General Characteristics

In 2002, Guatemala boasted around 13 million people, more than half of whom are full-blooded Mayan Indians, many of whom could not speak Spanish, the official tongue. Two other groups included the ladinos (of European and Indian blood), and those of unmixed European origin, the latter controlling most of the country. Roughly two-thirds of the country is literate, with 60 percent speaking Spanish, and the remaining 40 percent one of the Amerind tongues, principally Kíché, Kaqchikel, Q'eqchi and Mam. Its religions included Roman Catholic, Protestant and traditional Mayan. Just to the south of Mexico, Guatemala occupies an area of 108,890 square kilometers (41,801 square miles).

The country is divided into a fertile coastal plain and the altiplano or highlands, where reside the majority of non-Spanish speaking Mayans. In 1996, a 36-year civil war between the Mayas and the government ended. In 2002, relationships between that government and its people, including the press, were still being adjusted.

Guatemala has four major daily Spanish language newspapers: Prensa Libre, El Periódico, Siglo XXI, —all morning publications—and La Hora, an afternoon paper. Also publishing are one minor daily tabloid, the somewhat sensational Nuestro Diario, as well as two weekly periodicals, Critica and Crónica. All exceptand Crónica are independent. The major independent newspapers regularly criticize the government and military as well as other powerful segments of Guatemalan society. They have published reports on alleged government corruption and/or drug trafficking, using sources such as human rights groups, clandestine intelligence, or left-leaning organizations like the news agency CERIGUA, which had to operate in Mexico for most of the guerrilla war, or the Centro para la Defensa de la Libertad de Expresión (Center for the Defense of Freedom of Speech). Both Critica and Crónica had been equally independent, but the latter was the target of an advertising boycott in 1998 and was forced to sell to a conservative owner. In 2002, Crónica reflected the new owner's right-wing philosophy, while Critica continued to be critical of the government.

Additionally, there was the English-language daily The Guatemalan Post, as well as the oldest surviving newspaper in Central America, the Diario de Centro America. However, in the first decade of the twenty-first century, Diario de Centro America was a semi-official paper that reported legal news only, and has lacked the readership of many other papers.

The relationship between press and state in the first decade of the twenty-first century came about as a result of a history in which journalists usually wrote what the party wanted. Journalists' independence was, in 2002, less than a decade old.

Historical Background

The first "journalists" in what is now known as Guatemala were Mayan dispatch runners, but the glory days of the Maya were long past when the Conquistadores arrived in the early sixteenth century. For reasons which have never been entirely clear, Mayan cities and temples were unoccupied, crumbling into decay and covered with jungle vegetation at Pedro de Alvarado's arrival.

In the post-conquest period, almost all Central America was controlled from Guatemala. In 1729, Gazeta de Goatemala became Guatemala's first newspaper, and only the second in the New World. It was little more than a propaganda sheet, allowed to express only opinions pleasing to governors, clergy, and crown. The press confined itself to official or Catholic pronouncements, local items, and information about Spain, with the journal's license dependent upon cooperation with the authorities. This began a history of cooperation between press and state in Guatemala, examples of which remain in recent times.

Guatemala City became the capital in 1776, and the nation gained independence from Spain on September 15, 1821. The early nation was an essentially feudal society, one in which the press continued primarily to serve the state, which was in effect a succession of large landowners, known as caudillos, or "old families."

In 1880 Diario de Centro America was founded, it is the oldest surviving newspaper in Central America. June 1922 saw the birth of El Imparcial, different from other papers in that it took an independent stance for many years, eventually drifting to the right until finally becoming a pro-government and anti-Communist organ as the Cold War heated up.

In the 1940s, events took a turn which had a decided impact upon the development of Guatemalan journalism. Revolution, political turmoil and mounting discontent in 1944 ushered in the era of Juan José Arévalo, a liberal president, and a freely elected government. Several newspapers from both sides of the political fence came into being, two of which still exist today, La Hora, which came into being in 1944, and Prensa Libre (1951). Something close to true freedom of the press prevailed and earned applause from many places. In the 1950 elections, Jacob Arbenz Guzmán won election as the country's president.

In 1953-54 the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency helped train and back an invasion of Guatemala launched from Honduras by a mercenary army. Although Guatemalans did not take up arms, the government lost the backing of the military and this led to Arbenz's relinquishing his office, which was seized by Castillo Armas. Guatemala gained a reputation as one of the world's worst human rights violators, and freedom of the press became non-existent.

The struggle became a 36-year-long civil war, and people who worked for newspapers were often caught in the crossfire—in some cases, quite literally—between government right-wing army troops and Mayan and/or communist guerrillas. Right-wing death squads killed or threatened to kill journalists; left-wing terror groups did the same. As an example of the entire war's effect upon the civilian population, consider the brief presidency of Jose Efraín Ríos Montt, whose counter-insurgency campaign resulted in about 200,000 deaths of mostly unarmed indigenous civilians. The military carried out many of these missions, according to the Historical Clarification Commission (CED), which estimated that government forces were responsible for 93 percent of the violations. The Archbishop's Office for Human Rights said that the military was responsible for around 80 percent of violations.

"During the long period of armed confrontation, even thinking critically was a dangerous act in Guatemala, and to write about political and social realities, events or ideas meant running the risk of threats, torture, disappearance and death," said the Historical Clarification Committee. La Nación reporter Irma Flaquer Azurdia and her son died during an ambush in 1980. Right-wing squads also have been blamed for the 1985 disappearance of U.S. journalists Griffith Davis and Nicholas Chapman Blake; in 1993, the founder and editor of El Gráfico, Jorge Carpio Nicolle, was ambushed and murdered by more than 30 hooded men. The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) has said that more than 29 journalists were killed for doing their jobs during the conflict. In 1995, the Inter-American Press Association reported that evidence from the crime scene of the Jorge Carpio Nicolle assassination had disappeared, further hampering the investigation. In another instance, Siglio XXI columnist Hugo Arce's criticism of the president allegedly caused Arce to be arrested and charged with possession of dynamite and drugs. In 1993, Robert Brown summed up the position of the press with these words: "Death threats, physical attacks with armed thugs, the burning of newspapers … are done with total impunity."

The lines between journalism and politics in Guatemala often were blurred. For example, the assassinated Jorge Carpio Nicolle was not only a newspaper publisher but a candidate for several important political offices, and the same was true of his brother, Roberto. The Carpio and Marroquín families owned four of the eight dailies in 1982; Clemente Marroquín not only founded La Hora and was arguably the best-known journalist in the country, but also was vice president from 1966 to 1970. The founder of La Nación, Roberto Giron Lemus, was a presidential press secretary; General Manager Mario Ribas Montes of El Imparcial, who was assassinated in 1980, had been ambassador to Honduras.

During the guerilla war, several attempts to publish a paper with an anti-government point of view were made, perhaps the most typical of which was Nuevo Diario in the late 1970s. Not overtly seditious, it quietly attempted to investigate the government. The Secret Anti-Communist Army allegedly made death threats against Editor Mario Solorzano, causing him to flee the country. Allegations also were made that staff members were threatened, and reporters mugged or kidnapped; advertisers refused to contribute, and the newspaper collapsed in 1980.

Journalists were poorly paid. In 1975, monthly pay was supposed to range from U.S. $152 for a photographer to $253 for a reporter/editor, but very few journalists received that much. Most working reporters came from the lower middle class, with little or no training—journalism being considered a low-prestige occupation—were willing to accept the low pay in exchange for a chance to get to know the right people in politics and business and perhaps get a better job. Such reporters were not likely to be critical, and indeed, rarely were. In addition, allegations of money offered under the table for favorable reporting were often present, a form of bribery known as fafa. What it amounted to was that the press had a decidedly conservative bias and a strong desire to not rock the government boat.

With no redress seen for the conditions that had confined a majority of the indigenous population to the highlands attempting to live off plots of land so small they could not feed even the people who farmed them, guerrilla military activity began and reached its peak in 1980-81. The guerilla army numbered 6,000 to 8,000 armed irregulars and between 250,000 and 500,000 supporters throughout the country. In 1982, the insurgents came together to form the Unidad Revolucionaria Nacional Guatemalteca (URNG), thus creating a viable military and political entity which concerned the government's generals. Members of the ruling class coupled fear of a successful Castro-like revolution with the irregularities that characterized elections and began to question the generals' governing ability. Although the military continued to refuse to negotiate with the rebels, outside pressures came to bear in the form of peace treaties being negotiated in El Salvador and Nicaragua, as well as the ending of the Cold War.

In 1987, peace-seeking Guatemalans formed the National Reconciliation Commission (CNR) chaired by Msgr. Rodolfo Quezada Toruño of the Catholic Church Bishops' Conference. NCR began a "Dialogo Nacional" calling for a political settlement of the civil war. Although the military and other members of the ruling class ignored them, the CNR met with the URNG in Oslo and Madrid. After an agreement in principle was reached, the guerillas agreed not to disrupt the 1990 elections, which saw Jorge Serrano elected president.

Serrano began to negotiate directly with the URNG, involving the rebels in the political process for the first time.

Serrano's record was spotty; he had some success in reducing the influence of the military and persuaded military officials to talk to the rebels directly, but in 1993 he illegally dissolved Guatemala's Supreme Court and Congress, as well as restricted civil rights and freedoms in a self-initiated coup or autogolpe. Faced with united opposition he fled the state, and Guatemala's Congress elected Human Rights Ombudsman Ramiro De León Carpio to complete the presidential term. Under the new president, peace negotiations intensified and a number of pacts with the rebels—for resettlement of refugees, indigenous rights, and historical clarification—were signed.

In 1995 center-right National Advancement Party (PAN) candidate Alvaro Arzú was elected to the presidency. In December 1996 Arzú signed a peace treaty with the guerrillas, ending the 36-year civil war. Along with peace came changes to the press.

Economic Framework

In 2000, agriculture accounted for 25 percent of the gross national product and employed more than half the labor force, a staggering 60 percent of whom were below the poverty line. About 2 percent of the population owned around 70 percent of Guatemala's land, with the remainder mostly not arable. Almost one-third of the population is illiterate, but that figure is much higher among the impoverished who, by and large, are Mayan. Although the four major daily newspapers are privately owned and independent, their audiences primarily consist of the relatively well off.

Although the signing of the peace accords had the further effect of diminishing violence against journalists, there are other pressures on the press. Marylene Smeets of the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) said that, "Guatemalan journalists have compared this to a spigot. If they print good news, money flows in. If they print bad news, the money dries up." She also pointed out that "problems with advertisers also arise without government instigation. To write that a particular brand of automobile is the one most frequently stolen is to lose that brand's advertising."

Reporters are not without fault. Fafa continued to exist, albeit somewhat less frequently.

Press Laws

In 2000, the U.S. Department of State reported that the Guatemala Constitution provided for freedom of speech, including the press. By 2002, the letter of the law remained unchanged, and the government claimed to be working to improve its implementation of the law.

In addition to the Peace Accords of 1996 settling the civil war, the Accords pledged to enact reforms to the Radio Communication Law to make radio frequencies available for the indigenous Mayan communities, a matter of importance since most of that population could not speak Spanish. However, the government instead passed a law creating a public auction for radio frequencies and the resultant high cost proved an "effective barrier to rural indigenous access to radio frequencies," according to the U.S. Department of State. As of 2000, there were no radio stations solely for Mayans, although occasional broadcasts, speeches, and Spanish-language instruction was broadcast in the various indigenous tongues.

Censorship

In 2000, the U.S. Department of State found that the Guatemalan government usually respected the rights granted the press in its constitution, adding, however, that journalists had been threatened and intimidated, and finding at least two examples of "government-connected censorship." The government developed public information programs that radio and television stations had to broadcast. The government owned seven nationwide television channels; in 2002, one was being used by a Protestant group and the other by the military, with plans pending to sell the military channel to the Catholic Church. President Alfonso Antonio Portillo said the sale would provide competition for the four major stations that were monopolized by one man, Angel González of Mexico, a close friend and financial supporter of the president.

State-Press Relations

In May 2002, CPJ's Smeets reported that the press was showing signs of independence. CPJ said that "the virtual halt of violence against journalists suggests how dramatically conditions have improved for the Guatemalan press." However, that observation proved somewhat sanguine.

On June 5, 1997, a few months after the signing of the peace treaty, Jorge Luis Marroquín Sagastume, founder of the monthly Sol Chortí, which was investigating alleged corruption in the mayor's office of the town of Jocotaan, was murdered by two killers who, when apprehended, said they had been hired by the mayor. In November 1997, the head of the weekend section of Prensa Libre was stabbed by an unknown assailant, dying three hours later in the hospital.

The CPJ said that in 1997 the press had become more pluralistic and professional, but was "still hindered in its work by a climate of violence and growing tensions with the government of President Alvaro Arzú Irigoyen." It added that at least one other journalist had been killed in that year, "but against a backdrop of growing crime it was impossible to determine if the killings were motivated by their reporting."

Despite the apparent risks, journalists have reported aggressively on once-taboo subjects such as alleged government corruption, the drug trade, and possible human rights abuses by the military. Indigenous issues also have received increasing attention, not only from regional newspapers, but from Guatemala City dailies like Siglo Vientiuno.

President Arzú surprised everyone when he said publications were exaggerating violence in order to sell newspapers. Smeets described a publicly-funded television news show, Avances, supposedly in existence to inform the public about the government, but actually being used to promote the party in power.

Writing in 1998, Smeets saw violence diminishing against journalists, but felt that Arzú presented a new threat to freedom of the press. Although journalists tried to report objectively on a rising crime wave, the president felt that such reporting discouraged tourists. He continued to criticize newspapers for exaggeration and negativity, using his influence to try to deprive them of needed advertising revenue. For example, owners of the independent weekly Crónica felt forced to sell the magazine when all official agencies were forbidden to advertise in it. The new owners appointed right-wing and presidential friend Mario Davis García as editor, after which most of the publication's reporters promptly quit in protest.

Some Guatemalans said the well-known radio program Guatemala Flash changed hands from an owner who criticized the government freely to a pro-government investor because of similar pressure. Journalists were denied access to official information, on the grounds that it was privileged. It was alleged that the presidential spokesman, Ricardo de la Torre, regularly met with officials and urged them to ignore publications that were critical or negative, especially of the government. Eduardo Villatoro, ex-president of the Guatemala Journalists Association and a columnist for Prensa Libre, said that the "government does not realize that political space and freedom of expression are not gracious concessions of the government, but hard fought gains."

Although the CPJ found the same pressures on a free press in Guatemala in 1998, it also saw reason for encouragement. Of the three reported cases of press harassment, only one could be documented and the police officer involved was fired. Although under some financial pressure, El Periódico continued to improve its investigative reporting while maintaining its independence. (The newspaper had been purchased in 1997 by the same publisher who owned the independent Prensa Libre. ) Despite government interference, the Guatemalan press as a whole became increasingly independent and professional in 1998. The CPJ said that the Asociación de Periodistas de Guatemala (APG) joined the International Freedom of Expression Exchange Clearing House.

Arzú's hostility toward the press abated in 1999 but not for ideological reasons—it was an election year. The results ended his four-year term. Arzú may have lowered his criticism but he continued to work against journalism in other ways. For instance, a radio program devoted to discrediting print journalists and opposition members was found to be run by a special advisor to the ex-president.

It had only been three years since the cessation of the guerrilla war, yet reporters often tiptoed gingerly around sensitive areas, such as any alleged links between the drug trade and the generals. Journalists were still threatened, though not as often. In May 1998 El Periódico revealed that two of its reporters were trailed by members of the presidential security detail. In the past, it was likely the paper would not have reported on a matter like this, so many felt progress had been made. In addition, the two brothers accused of murdering Sol Chortí founder and director Jorge Luis Marroquín were tried, found guilty, and sentenced to 30 years in prison.

In April 1998, a radio program called Hoy por Hoy (Day by Day) broadcast a series of indictments aimed at print journalists; in particular, Prensa Libre owner Dina García and editor Dina Fernández were singled out as incompetent reporters and immoral women, although they were neither. The staff of El Periódico suspected Arzú, and an investigation found a link. On June 17, headlines trumpeted: "Who's Behind Hoy por Hoy ?" The answer: Mariano Rayo, special adviser to the Arzú. Called before a congressional hearing, Rayo offered to resign, but Arzú refused to hear of it. Eventually, Rayo was elected a deputy to the Legislative Assembly. Fernández summed up the affair: "In any other country this would have destroyed [him]… Here they reward him …"

Attempts to improve the quality of journalism were made in 1999. Media organizations tried to end fafa, al-though they were not completely successful. The APG began a dialogue about the need for a professional code of ethics.

Under the presidency of Alfonso Portillo Cabrera, and despite frequent but somewhat diminished intimidation and threats, the press continued to pursue risky activities such as investigating the military, politicians and the Guatemalan equivalent of the CIA. Former President Ríos Montt re-surfaced as president of congress and ally of the incoming president, and a target of a journalistic investigation into a conspiracy to reduce taxes on alcohol. Prensa Libre broke the story; editor and columnist Dina Fernández said, "Unlike in the past, we did our job and didn't remain silent."

On May 15, 2000, El Periódico accused the Estado Mayor Presidencial, or Presidential High Command, of running a clandestine intelligence agency, the director of which was an ex-military official. The previous day, a reporter for that paper had been followed by an unmarked car with concealed license plates; several other journalists on the case were either followed or received intimidating phone calls. Eight days after the story broke, Siglo Veintinuno said a journalist from Nuestro Diario was threatened during a phone call, a staffer for the radio show Guatemala Flash was faxed a death threat, and two reporters from Siglo Vientiuno itself were threatened. CERIGUA, the left-leaning news agency that had recently arrived from Mexico, also reported being threatened more than once over this case. On May 19, the CPJ sent a letter to Attorney General Adolfo González Rodas, detailing and protesting the intimidation, and calling for him to "take adequate measures to ensure that journalists working in Guatemala are able to work safely, without threats or intimidation."

In July, "An Open Letter from the pro-Army Patriots to the People of Guatemala" was paid for and appeared in Siglo Vientiuno. In it, El Periódico publisher José Rubén Zamoro was identified as one of those "seeking to destroy the army," and it added that from "now on [our intention] must be made firm and clear [it is]…to defend the institutionality of the army and our sovereignty."

All of the journalists threatened in 2000 were not harmed, but some were. Prensa Libre photographer Roberto Martínez was shot and killed by private security guards while covering a demonstration against an increase in bus fares. The guards opened fire on the demonstrators, hitting Martínez despite his clearly being a journalist and his camera being visible. Two bystanders also were killed, and Julio Cruz, a reporter from Siglo Vientiuno, as well as Christian Alejandro García, a cameraman from the television news show Notisiete were hospitalized. Other journalists surrounded and detained the two security guards until police arrived and arrested them. The two were awaiting trial as the year ended. Centro para la Defensa de la Libertad de Expresión, or CEDEX, a newly created organization, issued a communiqué condemning the killing.

In 2001, freedom of the press somewhat deteriorated in Guatemala, as did the political stability of President Portillo's nation. In February, the staffers of El Periódico were threatened by a mob whose members claimed to be protesting that newspaper's investigation of corruption on the part of governmental minister Luis Rabbé. The CPJ's protest letter to Portillo said the mob tried "to force the daily's doors open and threw burning copies of the newspaper into the building," additionally burning an effigy of publisher José Rubén Zamora. The police took 40 minutes to arrive and arrested nobody when they did. Portillo denounced the attack but did nothing to prevent further protests. The following month, four reporters from the paper were attacked and threatened after investigating a bank under state control. Crédito Hipotecario Nacional was revealed by Silvia Gereda and Luis Escobar to have loaned huge amounts of money to friends of the bank's stockholders and the president, José Armando Llort, who responded by taking out newspaper ads threatening libel suits against the journalists. In March, an anonymous man told Gereda that she and her friends were being filmed, and that the bank president wanted them killed. Later she was followed by an unmarked car and threatened several times. A colleague had a gun pointed to his head and was told if the investigation continued, all would die. Portillo, in the face of mounting national and international pressure, is believed to have personally asked the bank president to resign.

In April, the president of congress, Ríos Montt, whose presidency and anti-insurgency policies had resulted in the deaths of more than 200,000 mostly innocent Guatemalans, complained that the earlier investigation into the taxation of alcohol was part of a hidden agenda to discredit him and guarantee his "political lynching." Seven months later, according to CPJ, the investigation "was shelved after a highly controversial court ruling."

In June, the Centro para la Defensa de la Libertitad de Expresión, a Guatemalan freedom of the press group, had its inaugural seminar. In November, ironically voting on Guatemalan Journalists Day, the congress required all college graduates, including journalism students, to register with colegios or trade associations. Portillo was asked to veto the new law by many press freedom organizations—including some international organizations and the APG—and said he would do so if he felt the bill could damage journalists.

A penalty for the murder of a journalist was carried out in February 2001 when the security guard who killed Roberto Martínez was sentenced to 15 years in the penitentiary and his company ordered to pay damages equivalent to U.S. $20,000 to his family.

As 2002 enfolded, at least one more case of journalistic intimidation had already taken place. On April 10 in downtown Guatemala City, David Herrera, a freelance reporter working for Enlaces, a group of journalists, was kidnapped and threatened with death. Herrera, working on a story recounting alleged government-sanctioned killing, was manhandled by four unknown men brandishing handguns. The men apparently wanted to know where Herrera had the notes he and a colleague had collected concerning the case. The men had searched Herrera's truck, but apparently did not find what they were looking for. The men told Herrera they were going to kill him, and when one cocked a gun, Herrera jumped from the moving vehicle and fled back to his office. Herrera required medical attention for shock. CPJ sent a letter of protest to Portillo, but three months later he had not yet answered.

Despite the arrival of peace in Guatemala, violence against journalists lingered, but at a significantly reduced pace when compared to earlier years. Although the government still did not seem willing to allow a totally free press to exist, the press itself showed great improvement in directly confronting the government, something it would not have dreamed of just a decade earlier.

Attitude Toward Foreign Media

In a nation where right-wing death squads were blamed for the 1985 disappearance of U.S. journalists Griffith Davis and Nicholas Chapman Blake, conditions towards foreign journalists in post-Peace Accords Guatemala were greatly improved. Since 1996, there have been no instances of hostility reported towards reporters from other nations. The Inter-American Press was allowed to hold its "Unpublished Crimes against Journalists" conference in Guatemala City in 1997, which focused attention on cases such as the 1980 murders of journalists Irma Flaquer and Jorge Carpio Nicolle.

News Agencies

In 2002, foreign news agencies included Reuters and the Associated Press, as well as agencies from Spain, Germany, France, Mexico, the United States and Canada. Domestic agencies included ACAN-EFE, Agencia Cimak.

The news agency CERIGUA, which had had to operate in Mexico for most of the guerrilla war due to its left-leaning philosophy, opened an office in Guatemala's capital in 1994. It provides news from a leftist perspective, and in 2002, was continuing to function as independently as possible, including reporting on attempted intimidation. During 2000, CERIGUA helped reveal the existence of a clandestine governmental intelligence agency, despite numerous anonymous threats being made to it by fax and telephone.

Broadcast Media

In 2000, there are 26 stations, with all content emanating from one of four major outlets: Canal 3, Canal 7

Radio broadcasters numbered 632 stations. The content of both radio and television was determined by the government.

Although print journalists continued to grow into their roles as investigative reporters during the postwar period, those working in radio and television were, for the most part, stagnant. Part of the problem was money; small cooperative radio stations could not afford to bid on frequencies offered at public auction. In a land where radio is the dominant medium, larger stations had more money to bid than did Mayan groups, which demanded improved media access but did not get it despite the 1996 peace accords call for specific indigenous language radio frequencies.

Violence was not limited to members of the print press. On June 16, 1997, a news reader at Radio Campesina in Tiquisate, Herández Pérez, was shot and killed while leaving the station. Also killed was a station messenger, Haroldo Escobar Noriega. In 2000, Christian Alejandro Garcia, a cameraman from the television news show Notisiete, was shot by security guards while covering a demonstration against higher bus fares and had to be hospitalized. In the same year, a staffer for radio show Guatemala Flash was faxed a death threat over that station's investigation of the government's unofficial intelligence agency. Finally, less than two years later, the

Governmental pressure of a subtler sort also could be seen at times. Some Guatemalans said that Guatemala Flash changed hands from an owner who criticized the government freely to a pro-government investor because of government pressure aimed at advertisers. A publicly-funded television news show, Avances, was supposed to inform the public about the government but spent most of its time criticizing the print press. The radio program Hoy por Hoy broadcast indictments aimed at Prensa Libre owner Dina García and editor Dina Fernández. President Arzú was found to be behind the false allegations.

Charges were made that it is impossible for an independent radio and television media to emerge in Guatemala because so many stations were owned by so few of the people. It has been pointed out that a Mexican national, Angel González, owns all four of the private Guatemalan television stations as of June 2002, despite laws against both monopolies and foreign ownership. Many felt that Portillo, despite his protests to the contrary, was behind González's closing of an occasionally controversial news show known as T-Mas de Noche. Portillo denied any involvement and invited the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights to investigate, which it did. The result was that the investigator urged the government to look into González's holdings, as well as recommending the suspension of the public auction of broadcast radio frequencies in order to make at least some of them available to the indigenous population in appropriate languages. Shortly thereafter the auctions were suspended. But in mid-2002, there were no indigenous broadcast channels for either radio or television. However, occasional broadcasts and speeches were given in Mayan tongues.

Electronic News Media

In the year 2000, there were five Internet service providers. The number of Internet users is rapidly increasing, especially among journalists who use it for both information and training purposes. The Internet functions government interference. Smeets said the Internet opened the eyes of Guatemalan journalists and exposed them to a more professional, better-finished, more ingenious and creative press.

In 2002, four major dailies are available on-line: Prensa Libre at www.prensalibre.com.gt ; Siglo XXI at www.sigloxxi.com ; La Hora at www.lahora.com.gt , and El Periódico at www.elperiodico.com . Four television stations also are online: Canal 3 at www.canal3.com.gt ; Canal 7 / Televisiete at www.canal7.com.gt ; Canal 11 at www.canal11.com.gt , and Canal 13 at www.canal13.com.gt . Also online is the radio group Emisoras Unidas at www.emisorasunidas.com .

Education and Training

In 1998, the Asociación de Periodistas de Guatemala began work with San Carlos University to develop journalism workshops. By mid-2002, there were individual journalism classes at that university, but no degree program. The Internet supplied some journalistic training. Regarding journalism training in Guatemala, Smeets said Guatemalan journalists need better education opportunities to learn the skills necessary to analyze current events, and that better reporting will raise reader expectations, which "opens more space for independent journalism."

Summary

Before the Peace Accords, journalists were murdered, threatened, kidnapped, and were actually in the pay of the ruling classes, as were their newspapers. The print media, in particular, had become both more pluralistic and professional, as the CPJ observed in 1997. The same organization in 1998 referred to "the virtual halt of violence against journalists this year," so the profession has become safer. Although violence has escalated in recent years, it is still nowhere near what it had been. The government does try to influence newspapers, for instance, by encouraging the withholding of advertising revenue.

In the case of television and radio, there is less reason for optimism. The government's virtual monopoly over television, coupled with its control over radio channels, is a threat to freedom of the press, especially in a nation where nearly one-third of the population is illiterate. Control of these media outlets has dire consequences for the Mayan-speaking majority of Guatemalan Indians, whose primary access to the news is radio and television. In the first two years of the twenty-first century, there is neither a television nor radio station for these people, although there is an occasional radio program or speech in an indigenous language.

By the halfway point of 2002, it is not yet clear if either President Portillo or any members of the power structure he represents, including the generals, has intentions of democratization. Guatemala was brought to the Peace Accords by a combination of external pressure and the internal recognition that the war was basically unwinnable. Portillo and his backers may have intended to implement the Peace Accords and were perhaps slowly, but inevitably, progressing towards this goal. Or they may have regarded the peace process as an extension of the civil war, one in which they worked their hardest to keep the status quo while giving the illusion that they intended to become more democratic. Ultimate freedom of the Guatemalan press is dependent upon the freedom of the Guatemalan state.

One thing, however, seems evident: The full participation of the highland-dwelling indigenous people of Guatemala will be necessary before there is any sort of democracy or true freedom of the press. There is a synergistic relationship between a free press and a free and literate people; when people cannot read or at least hear and see for themselves what their government is doing, that synergy cannot exist. In Guatemala, it has never had a chance to develop.

Too many Guatemalans remain incapable of taking part in a democracy; they cannot understand the Spanish of the press, or they cannot read at all. Until they can fully participate, their nation's press continues to exist only for its literate and Spanish speaking members.

Bibliography

Brown, Robert U. "Curtailing Press Freedom." In The Fourth Estate, 128, April 8, 1995, pp. 31-3.

Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs. "Background Note: Guatemala." Available from http://www.state.gov./r/pa/ei/bgn/2045.htm .

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). In The World Fact-book 2002. Available from http://www.cia.gov./cia/ .

Cleary, Edward L. "Examining Guatemalan Processes of Violence and Peace." In Latin American Research Review. January 2002, 37, no. 1, 230-246.

"Country Reports: Guatemala." The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, and 2001. Available from http://www.cpj.org .

Ebel, Roland H. Misunderstood Caudillo: Miguel Ydigoras Fuentes and the Failure of Democracy in Guatemala. New York: University Press of America, 1998.

Embassy of Guatemala to the United States. Available from http://www.guatemala-embassy.org .

Jonas, Susanne. Of Doves and Centaurs: Guatemala's Peace Process. Santa Cruz, Ca.: Westview, A Member of the Perseus Books Group: 2000.

Lawyers Committee for Human Rights. Abandoning the Victims: The UN Advisory Services Program in Guatemala. New York: The Lawyers Committee for Human Rights, 1990.

Lovell, George W. A Beauty that Hurts: Life and Death in Guatemala. Austin, Tx.: U of Texas, 2000.

McCleary, Rachel M. Dictating Democracy: Guatemala and the End of Violent Revolution. Gainesville, Fl.: U P of Florida, 1999.

Nelson, Diane M. A Finger in the Wound: Body Politics in Quincentennial Guatemala. Los Angeles: U of California P, 1999.

Nichols, John Spencer. "Guatemala." In The World Press Encyclopedia, George Thomas Kurian, ed. New York: Facts on File, Inc., 1982, 409-420.

Simon, Jean-Marie. Guatemala: Eternal Spring—Eternal Tyranny. New York: W.W. Norton Co., 1987.

Smeets, Marylene. "Speaking Out: Postwar Journalism in Guatemala and El Salvador." Available from http://www.cpj.org/attacks99/americas99/americasSP.html .

"Station May Go Catholic." In Chicago Sun-Times, June 14, 2002, p. 43.

Trudeau, Robert H. "Understanding Transitions to Democracy: Recent Work on Guatemala." In Latin American Research Review, 1993, 28, no. 1, 235-49.

Von Hagen, Victor W. World of the Maya. New York, New York: The New American Library, 1960.

U.S. Department of State. "Guatemala: Country Reports on Human Rights Practices 2000." Available from http://www.state.gov./g/drl/rls/hrrpt/2000/wha/775pf.htm .

Zur, Judith N. Violent Memories: Mayan War Widows in Guatemala. Boulder, Co.: Westview Press, a member of HarperCollins Publishers, 1998.

Ronald E. Sheasby , Ph. D.