Guyana

Basic Data

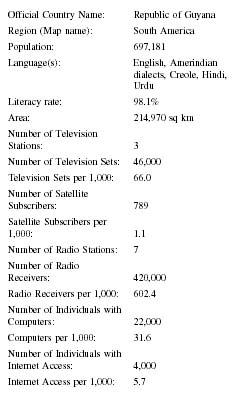

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Guyana |

| Region (Map name): | South America |

| Population: | 697,181 |

| Language(s): | English, Amerindian dialects, Creole, Hindi, Urdu |

| Literacy rate: | 98.1% |

| Area: | 214,970 sq km |

| Number of Television Stations: | 3 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 46,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 66.0 |

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 789 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 1.1 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 7 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 420,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 602.4 |

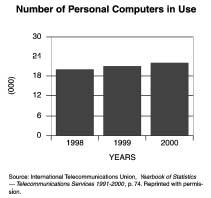

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 22,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 31.6 |

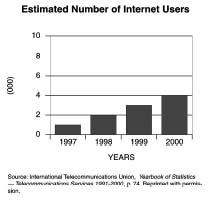

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 4,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 5.7 |

Background— General Characteristics

Guyana (full name, Co-operative Republic of Guyana) is a tropical country lying on the northern coast of South America. The sparse population of the country's savannahs and highland regions consists mostly of Amer-indians, Guyana's indigenous people. The capital, and the country's main harbor, is Georgetown, whose population is around 185,000. Guyana is comprised of six ethnic groups, which reflect the fact that modern Guyana began as a nation of plantations run by Dutch, French and British settlers who imported slave labor. Around 40 percent of the population is African; East Indians comprise 51 percent, and the remainder are Chinese, Portuguese, European, and Amerindian. The official language of Guyana is English, but other languages are spoken, including several Amerindian dialects, Creole, Hindi, Urdu and Creolese, which is a mixture of English and Creole. Guyana is a secular state, but everyone is guaranteed religious freedom under the Constitution. About 57 percent of Guyanese are Christian; Hindus comprise 33 percent; and 9 percent are Muslim.

The country's varied terrain, extensive savannahs, mountainous regions, and dense forests have made communication difficult and have divided the country's newspaper publication into two distinct groups: newspapers published in remote regions for local consumption, and those published in Georgetown. The largest savannah occupies about 6,000 square miles in the southwestern part of the country and is divided by the Kanuku mountain range.

The country's major newspapers are published in Georgetown and must be shipped to interior regions either by air or boat because of the country's terrain. Only unpaved roads and trails link the savannahs and interior towns. The main paved roads are located in the coastal area and extend through the towns and villages near the coast. Consequently, rivers are an important means of transportation to the country's remote areas. Air communication is the main link to the interior of Guyana, which is served by about 94 airstrips, most of which receive only light aircraft.

Regional newspapers traditionally have been small, both in readership and in the kind of news printed. By contrast, newspapers published in the capital have had a much broader scope and larger circulation. Journalists would also be affected by the country's geography. The better trained, more experienced, and better educated journalists would gravitate to the capital, where the readership was larger and press facilities were more advanced than in the smaller cities and remote villages.

Guyana's first known newspaper, the Royal Essequibo and Demerary Gazette, was published in 1796 by the government, but it was small and filled almost entirely with advertisements. In the nineteenth century a series of private newspapers, such as the Creole, frequently sprang up all over Guyana, but they usually lasted only days or months, and sometimes mere hours. They had little or no financial support and their publishers, who doubled as reporters, lacked formal training or professional experience. One of these early efforts, the Working Man, may have been typical of these amateur newspapers. It championed the cause of the poor and working class in opposition to powerful forces in the colony. Predictably, Working Man failed to attract advertisements from influential businesses and, like other small newspapers, succumbed before the year was out. By the 1940s, newspaper publication was centered in the capital. Three dailies were being published: Daily Argosy, Guiana Graphic, and Daily Chronicle, all privately owned and all serving a population of about 75,000.

Although newspapers have been part of Guyana's history for 200 years, literacy among the non-European population did not begin until 1876, when universal primary education was introduced; the establishment of secondary schools early in the twentieth century helped spread literacy. Today, the government reports an overall literacy rate of 98 percent, but research indicates that the average literacy rate is actually much lower if measured in terms of the basic ability to sign one's name. Other studies show that the overall functional literacy rate is a little more than 50 percent.

Historical Background

Guyana was first populated by the indigenous peoples of the region, the Amerindians, comprised of nine aboriginal tribes. European settlement began in 1615 with the Dutch West India Company, which established plantations on the coast and brought West African slaves to work the newly established cotton and sugar plantations. The French and English soon laid claim to various parts of the region, bringing in their own slaves to work their plantations. From 1781 onwards, the British became the dominant power, ultimately uniting various colonies into British Guiana. When slavery was abolished in 1834, laborers were brought from India to work the plantations in place of the former slaves who left. Immigrants also came from Europe and China.

British Guiana gained independence in 1966, giving birth to the new country of Guyana, which adopted its own constitution in 1980 and a new economic philosophy, co-operative socialism. Many industries were nationalized, and many educated Guyanese emigrated in response to these changes and to the economic slump that hindered the country's growth into the 1990s. In recent years Guyana was attempting new economic initiatives to try to reverse the lingering effects of the recession of the 1970s and 1980s, and though it was making encouraging progress on many fronts, more than half the population lives in poverty. In an effort to relinquish control of industry, the ruling party is privatizing many businesses, and has liberalized its stance toward the media by funding professional courses in journalism at the University of Guyana.

The Guyanese press was established in 1793, and politics have sometimes played a part in which publications survived and which did not, and in how the survivors fared. During World War II, the government established the Bulletin, a free publication that promulgated news of the government's war efforts. Later, the Bulletin was expanded into a full-fledged newspaper with a circulation of around 52,000, the country's largest at the time, to deliver the state's propaganda across Guyana. The Bulletin 's function as a dispenser of information, not a gatherer of news, has remained the government's version of media participation ever since. Over the years, and despite the country's small population, a plethora of periodical publications have come and gone. Each group serves specific areas of the country or special groups. For example, among the journals Polyglot: Journal of the Humanities publishes academic research for and by linguists. Newsletters and magazines offer an economical and expedient way to disseminate information for a wide variety of groups, such as accountants, the police, the University of Guyana History Society, Georgetown Sewerage and Water Commissioners, the Adult Education Association of Guyana, various alumni associations, religious groups, political parties, and many other groups. Visions and Voices, the newsletter of the National Democratic Movement, focuses mainly on Georgetown's social problems. Other newsletters deal with sports, HIV/AIDs, and current topics of interest to readers. GY Magazine aims to offer Guyanese women "a magazine of quality" with articles on glamour, health and fitness, romance, sex, and literature. The humanities are further represented by The Guyana Christmas Annual, a magazine of poetry, fiction and non-fiction, and photography. Sports Digest, a quarterly sports magazine, covers local sports from around Guyana. Emancipation, a magazine started in 1993, deals with the history and culture of the African-Guyanese and contains features on villages, personalities and literature. The Guyana Review has established itself as Guyana's preeminent national news magazine. A monthly publication, it offers a wide range of economic, environmental, political and cultural news.

Guyana's newspapers are relatively few in comparison to the country's other print media, but the combined circulation of all newspapers in the country is a little more than 407,850. Newspapers with the largest reader-ship are the Guyana Chronicle, a government-owned daily published in Georgetown, and New Nation, the voice of the People's New Congress, one of the two major political parties, with a circulation of about 26,000. Dayclean, published for the Working People's Alliance, was founded in 1979 and has a circulation of 5,000; its aim is to defend "the poor and the powerless" against abuses of power by the ruling party. The Mirror, owned by the ruling People's Progress Party, was begun in 1962 and grew to 16 pages by 1992. It is published twice a week in Georgetown and has developed a readership of about 25,000. Stabroek News is a liberal independent newspaper that started out as a weekly and increased to six times a week by 1991. The Catholic Standard, published by the Roman Catholic Church since 1905, has a readership of 10,000.

Several special-interest newspapers also are available. True News, published weekly in Georgetown, is aimed at a readership that likes sensational social, legal and medical stories. Flame, published in Georgetown by the National Media & Publishing Company Ltd., is a mid-week newspaper that offers "fascinating stories from Guyana, the Caribbean and the rest of the world" for an adult, mass readership. Civil Society, also a Georgetown weekly newspaper, offers cultural, political and social information in a manner intended to be thought-provoking. Guyana even has a weekly tabloid, Spice, which publishes sensational stories with racy photographs of young women.

Guyana's diverse geography has resulted in widespread racial separation, the Indians staying mainly in the rural areas and the Africans moving to the cities. Consequently, Indians on the plantation have long dominated the sugar and rice industry, and Africans now dominate the civil service and urban industries. But in the last 30 years, integration has increased as large numbers of Indians have settled in the cities, bringing new stresses as they mix with other races. The ethnic troubles of the 1960s divided the Guyanese people and have led to street violence, particularly around election times, and have raised fears of social disintegration. Turbulent politics and ethnic strife continue, and protests following the 1997 and 2001 elections increased political instability and often have threatened to bring the country's economic recovery to a halt. Through much of Guyana's history, the Anglican and Roman Catholic churches have helped maintain the social and political stability. The Roman Catholic Church and its newspaper, the Catholic Standard, opposed the ideology of the People's Progressive Party in the 1950s and became closely associated with conservative forces. In the late 1960s, the Catholic Standard became more critical of the government and, as a consequence, the government forced a number of foreign Roman Catholic priests to leave the country. By the mid-1970s, the Anglicans and other Protestant denominations had joined to oppose government abuses.

Economic Framework

Guyana's economy is dependent on a narrow range of products for its exports, employment and gross domestic product. Although Guyana is richly endowed with natural resources, it is one of the poorest countries in the hemisphere. Political antagonism and ethnic strife continue to hamper economic recovery and social reconstruction; consequently, the national spirit suffers as well. Nevertheless, some believe the biggest problem is the lack of experienced, educated people who can run the civil service, manage the country's institutions, and perform important administrative functions. A stable infrastructure and efficient bureaucracy would allow reform measures to progress and would provide the continuity the country needs in its struggle to remain viable.

Censorship

The 1980 constitution guarantees freedom of the press, but the government owns the nation's largest publication and exercises indirect control over other newspapers by controlling the importation of newsprint.

Guyana's present constitution provides for freedom of speech and of the press in the following words: "Every person in Guyana is entitled to the basic right to a happy, creative and productive life, free from hunger, disease, ignorance and want. That right includes…freedom of conscience, of expression and of assembly and association…." The government claims that it respects these rights. Indeed, Guyanese citizens openly criticize the government and its policies, but a rancorous relationship between the press and the government has existed since the country won independence from Great Britain in 1966. Journalists have been physically attacked during public protests.

The printed press has flourished despite opposition by the government, which also has been accused of trying to control the electronic media. The independent Stabroek News publishes daily, and a wide range of religious groups, political parties, and journalists publish a variety of privately owned weekly newspapers. The government has its own daily newspaper, the Guyana Chronicle, which covers a broad spectrum of political and nongovernmental issues. The country has three radio stations, all owned by the government. A government television station plus 17 independent stations are in operation. The Ministry of Information censors the Internet and restricts public access to a variety of sites.

From 1966 onward, the government, through the newly established Guyana News Agency, has sought to control the flow of information from within and outside the country. One of the agency's assignments was to gather "information about developments in Guyana— particularly in areas outside the city—and disseminating same to the Guyana in the form of news and feature articles, etc., via the print and broadcast media." Administrations before and after the 1980 Constitution have employed a variety of other techniques to stifle opposition. In the 1960s, the government purchased the independent Guyana Graphic, — whose editors had criticized the government—fired the paper's editors and created its own Daily Chronicle and Citizen newspapers.

The government also brought frequent charges of libel against editors who criticized the government. The opposition Stabroek News survived despite these conditions and has become widely regarded as the only reliable and nonpartisan source of news in Guyana. The Mirror, established in 1962, also remains free of state control. Although the government has declared publicly that it allows freedom of the press, the Mirror details several ways the government can and does interfere with the newspaper's freedom: the government has increased the cost of bonds, which are required to publish a newspaper, pamphlet, or leaflet; the government also controls the import of printing equipment, paper, and other supplies necessary for publishing a newspaper. It also uses "archaic libel laws" to pressure advertisers not to advertise in certain newspapers and has forced the closure of at least one newspaper, the Liberator. At about the same time the Stabroek News expanded operations in 1991, the Mirror was allowed to import new presses and increase its size from four to 16 pages per issue.

The days when the media were almost completely dominated by the ruling party seem to be numbered. The government's influence over the press has lessened, and increased criticism has flourished, but whenever a party is in power, it wishes to maintain its position by controlling the media. The state has retained control over the country's radio stations and is in no hurry to relinquish whatever control it still has over other media. Political rivalry is said to be the main reason for state control of the media; no ruling party wants to silence the media—the task would be doomed to failure and would expose the government to harsh criticism from within and from foreign sources. The government simply wishes to control the kind of information that is broadcast, and to that end, it needs the media.

Ironically, the media has come under criticism in recent years, and has been accused of being dominated by "vested interests" that interfere with the government's efforts to improve economic and social conditions, and to privatize the media and industry. Some claim the loud and persistent questioning of government policy and other media practices distort issues, and that by reporting on the country's crime, violence, and deteriorated social conditions, the media obscures the positive gains the government has made. Many voices in the country are calling for more balanced, fair news coverage.

State-Press Relations

Stabroek News regularly publishes editorials that openly criticize the ruling party and question the state of the country, and the practices of the ruling class. Although its editor has formally complained that government advertisements, a form of press subsidy, are allocated unfairly, the newspaper remains an important voice in Guyana's political and public affairs. Both of the major parties have committed themselves to the divestment of the state media. When the People's Progressive Party returned to power in 1992, it pledged that there would be "no government or state monopoly," and it guaranteed "private ownership in keeping with a pluralistic democracy and freedom of the media." It claimed it would also encourage "different shades of opinion" in the media.

Guyana's president recently joined 26 other heads of state to sign the Declaration of Chapultepec, which is based on the essential precept that no law or act of government may limit freedom of expression or of the press, whatever the medium of communication. The signing of the declaration by Guyana's president demonstrated to the international community that Guyana is not interested in returning to the ruthless denial of press freedom under the authoritarian regime that prevailed before 1992. The declaration, in part, embraces the following principles: freedom of expression and of the press is an inalienable right; every person has the right to seek and receive information, express opinions and disseminate them freely; no journalist may be forced to reveal his or her sources of information; the media and journalists should neither be discriminated against nor favored because of what they write or say; tariff and exchange policies, licenses for the importation of paper or news-gathering equipment, assigning of radio and television frequencies and the granting or withdrawal of government advertising may not be used to reward or punish the media or individual journalists; membership of journalists in guilds, their affiliation to professional and trade associations and the affiliation of the media with business groups must be strictly voluntary; and the credibility of the press is linked to its commitment to truth, to the pursuit of accuracy, fairness and objectivity and to the clear distinction between news and advertising.

The Declaration further states that "the attainment of these goals and the respect for ethical and professional values may not be imposed. These are the exclusive responsibility of journalists and the media. In a free society, it is public opinion that rewards or punishes; no news medium or journalists may be punished for publishing the truth or criticizing or denouncing the government." A careful reading of these guidelines not only reveals the government's ostensible desire to improve its relations with the country's press community but also gives, by implication, a clear picture of the abuses that have persisted since the country began.

Attitude Toward Foreign Media

In 1980, the government established the Guyana News Agency in order to control what kind of information from foreign sources was allowed into the country. The agency was assigned the task of "channeling overseas news to the local media, government leaders and other decision-makers, and other relevant publics, in Guyana and, through its missions overseas, to the relevant publics outside Guyana." The agency was also to provide "an editing service, eventually, for overseas materials, to give them a Third World orientation and make them more meaningful to the Guyanese readership." Some observers saw the agency's mandate as a thinly veiled attempt by the government to control information flowing into and from Guyana. The government, however, could not stop criticism from the foreign press and from those journalists ousted by the ruling party. This source of information and opinion continued to be an important counterbalance to the state's attempts to stifle media criticism within the country.

In general, as a member of the Caribbean community, Guyana cannot escape scrutiny by its neighbors. Its concerns are the concerns of the whole community. Information, ideas, and issues are given voice by The Guyana Caribbean Politics and Culture Web site, which bills itself as "a unique forum for conversation on Caribbean society… a Center for Popular Education whose main aim is to provide information and discussion as a means of empowering Caribbean people of all classes and station in life." To that end, it devotes a special section to "Opinions Views and Commentary on Guyana," where up-to-date information about Guyana and other members of the Caribbean community may be exchanged.

Broadcast Media

Guyana's communication system includes a government-dominated television and radio network. The country's two radio stations are owned by the government, which also operates one television channel. Two private television stations relay satellite services from the United States. A large number of private television channels are available that freely criticize the government. As of 1997, the Guyanese owned 46,000 television sets.

Electronic News Media

By the year 2000, about 4,000 Guyanese used the Internet. Several of Guyana's publications also may be found on the Internet. Stabroek News is perhaps the most dependable source of unbiased online news coming out

Education & TRAINING

Guyana's journalists have lacked professional training and formal education from the country's birth. Those who worked in the profession needed only a secondary education and many early reporters lacked even that much education. Wages were low and conditions were difficult. Those who wished to become established in newspaper publishing worked their way up from menial jobs to political reporting and then, if they were bright enough and committed, to an office job. Their salary would remain low, hardly enough to pay for basic necessities; they had no union, no pension, and no regular hours. They could be fined for inaccuracies in their stories, which had to be hurriedly written, and they could be dismissed without notice for insubordination or unpunctuality. To put journalists on a better footing, the government in 1975 funded a program at the University of Guyana, with the objectives "to provide development workers and planners, extension personnel, information and media practitioners…with a broad education aimed at improving their ability to understand and interpret social issues and the value of human communication in the development process; and, to give participants specialized

Summary

To broaden its readership, Guyana's press must rely on the government's efforts to improve the country's deteriorated educational system so more people will be better educated than they are and the dropout rate reduced. As a consequence of the decline of educational standards in recent decades, many adults are unable to read or write, and the finger of blame is pointed at Guyana's educational system, which is one of the worst in the Caribbean community. The Ministry of Education has created a "strategic development plan" to address this problem; meanwhile, the press suffers because many adults are illiterate. Many Guyanese feel that the country's future, not just the future of its newspapers, depends on better educating more people. To raise the quality of its profession, Guyana's press corps needs to be better trained. The University of Guyana is improving its programs in journalism, but for years the university lacked equipment, qualified staff, and other resources to offer adequate training, and progress has been slow. Without such professional training, journalists are not well respected. After a history of disorganization and poor schooling, the press corps suffers from a lack of professional solidarity and goals, professional ethics, adequate training and education, self-confidence, and self-respect. A strong union is needed to bring to all members of the country's media a sense of being among professionals whose social consciousness and training are equal to the task of gathering, analyzing, interpreting, and disseminating information for public consumption in a country still struggling to enter the new millennium.

At the same time, the government has made commendable strides toward relinquishing its control of the country's media, but the move toward total freedom of expression has not been completed.

Significant Dates

- 1980: in an effort to control information, the government created the Guyana News Agency, whose mandate was to "oversee news to the local media," to disseminate information about Guyana to the Guyanese, and to edit "overseas materials."

- 2000: The Guyana Press Association, dormant since 1995, was resurrected. It offers a means by which Guyana's press corps can, as an organized and self-governing body, address their own problems and set professional standards regarding ethics, education, and social responsibility.

Bibliography

Granger, David A. "Guyana's State Media: the Quest for Control." Stabroek News, June 18, 2000.

——. "Guyana's Press Corps and Its Problems." Sunday Stabroek, December 3, 2000.

Jagan, Cheddi. The West on Trial: My Fight for Guyana's Freedom. St. John's, Antigua: Hansib, 1997.

Jagan, Cheddi, and Moses Nagamootoo. The State of the Free Press in Guyana. Georgetown, Guyana: New Guyana Co., Ltd., for the People's Progressive Party, 1980.

Lee, Paul Siu-nam. Development Journalism, Economic Growth and Authoritarianism/Totalitarianism. Presented at the 38th Annual Conference of the International Communications Association at New Orleans, Louisiana, USA, 1988.

Morrison, Andrew. Justice: The Struggle for Democracy in Guyana 1952-1992. Published by Fr. Andrew Morrison, SJ. Printed and Bound in Guyana by Red Thread Women's Press, 1998.

Nagamootoo, Moses. Paramountcy over the Guyana Media: A Case for Reform. Georgetown, Guyana: The Union of Guyana Journalists, 1992.

Ratliff, William E. "Guyana." In Communism in Central America and the Caribbean, ed. Robert Wesson, 143-58. Stanford, Calif.: Hoover Institution Press, 1983.

Sidel, M. Kent. The Legal Foundations of Mass Media Regulation in Guyana: A Commonwealth Caribbean Case Study. Presented to the International Communication Division of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication Annual Convention inMontreal, Canada, August, 1992.

Spinner, Jr. Thomas, J. A Political and Social History of Guyana, 1945-1983. Boulder: Westview Press, 1984.

White, Dorcas. The Press and the Law in the Caribbean. Bridgetown, Barbados: Cedar Press, 1977.

Bernard E. Morris

Thanks in advanced

Bev