Iran

Basic Data

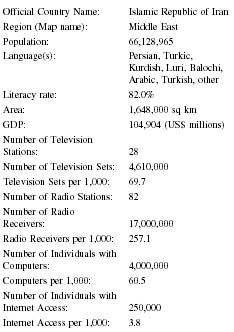

| Official Country Name: | Islamic Republic of Iran |

| Region (Map name): | Middle East |

| Population: | 66,128,965 |

| Language(s): | Persian, Turkic, Kurdish, Luri, Balochi, Arabic, Turkish, other |

| Literacy rate: | 82.0% |

| Area: | 1,648,000 sq km |

| GDP: | 104,904 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Television Stations: | 28 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 4,610,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 69.7 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 82 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 17,000,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 257.1 |

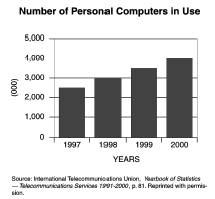

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 4,000,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 60.5 |

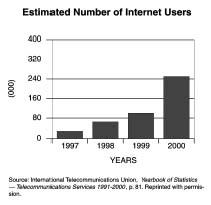

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 250,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 3.8 |

Background & General Characteristics

Islam has been the official religion of Iran since the Islamic Revolution of 1979. The media is accountable to Islamic Law and heavily censored by the ruling religious clerics. Conservative Iranians believe that Islam should be the rule of law in all of Iran: men and women cannot associate in public; the press cannot criticize government leaders who are also religious leaders; and other religious tenants must be upheld in social, cultural, and political arenas. There are many conservative publications in Iran such as Tehran Times , Joumhouryieh , and Resalaat . However, according to the "2001 World Press Freedom Review," a conservative editorial stance does not mean freedom from censorship and other forms of government control.

Reformists hold Islam in high esteem and want religion to maintain a prominent role in Iran. Reformists also desire freedom of association, freedom of the press, and a more open society: they believe a free press means a free people. Many reformist publications exist in 2002— for example, Iran Daily , Hayat-e-No , and Iran News — but all are frequent targets of censorship, confiscation, suspension, fining, and banning.

Journalism in Iran was a dangerous profession in the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, particularly if an individual worked for a reformist publication or adhered to a journalistic ethic of truth regardless of personal fate, which could mean threats, arrest, imprisonment with or without formal charges, accusation of espionage, isolation, or even torture, lashes, banning, murder, and execution.

Religion is of paramount importance to most Iranians. They may not want the ruling clerics to have control of every aspect of Iranian life, but the majority of citizens want Islam to play a strong role in the country. Secularism is not supported, and the Shah is used as an example of the failure of removing religion from the official operation of the state. According to the U.S. Department of State, Shi'a Muslims are 89 percent of the Iranian population; Sunni Muslims are 10 percent; and the remaining 1 percent is Zoroastrian, Jewish, Christian, and Baha'i.

Iran has an ethnically diverse population: Persian (51 percent), Azeri (24 percent), Gilaki and Mazandarani (8 percent), Kurd (7 percent), Arab (3 percent), Lur (2 percent), Baloch (2 percent), Turkmen (2 percent), and other (1 percent). This ethnic diversity results in tremendous language diversity: Persian and Persian dialects (58 percent), Turkic and Turkic dialects (26 percent), Kurdish (9 percent), Luri (2 percent), Balochi (1 percent), Arabic (1 percent), Turkish (1 percent) and other (2 percent).

In this nation of 66 million, 1996 data from the CIA World Factbook estimated that 53 percent of Iranians live below the poverty line; nevertheless, some 82 percent of the population is able to read and write by 15, which is also the age of universal suffrage. The population has more than doubled from 1979, when the Islamic Revolution deposed the Shah, to 2002, with the majority (over 60 percent) of Iranians under 30 years of age.

Economic Framework

In November 2001 Iran had the second largest population in the Middle East as well as the second largest economy, OPEC production, and natural gas reserves; however, economic problems persisted. High unemployment and isolation from the global community were causing problems and leading to backlash against clerical leaders who were beginning to realize that religion needs to find a more balanced place in society, so an entire generation, which desires religion and reform, is not lost.

Press Laws

Theoretically Iran offers constitutional protection for the press, but the lengthy Press Law outlining the purpose, licensing, and duties of the press shows the true limits placed on journalists. The Press Law details a long list of don'ts for journalists, preventing free publishing under threat of punishment, which is also detailed in the Law.

Iran's Press Law established the Committee for Suspension of the Press within the Ministry of Islamic Culture and Guidance. In 2002 the Committee, dominated by reformists, monitors the press and brings charges. Any charges brought on a newspaper or journalist are heard by the conservative-dominated Press Court (Public Court 1410, Tehran); the Revolutionary Court is even known to intercede and hear cases, though press issues are not technically in the Revolutionary Court's jurisdiction. All Press Court hearings and trials are to be open to the public, but this is not what happens in reality. Juries are mostly conservative and often ignored, dismissed early, or consulted after decisions are issued. From April 2000 to mid-2002, the judges in the Press Court have been pressing charges against individuals and publications, and circumventing the Committee.

Censorship

Press censorship is most common in the capital, Tehran. Censorship certainly occurs in the city, but it is self-censorship that is the largest concern in the provinces. Provincial journalists are cautious, lack funds, and have no modern printing operations. These small provincial papers have limited circulations; thus, the power of these papers as a source of news for the population is limited. Provincial Iranians have come to rely on international broadcast media—BBC, Voice of America, and Radio Free Europe—for information.

Between 1997 and 2001, Khatami's first term, "serial newspapers" and "serial plaintiffs" became common. A newspaper is labeled a "serial newspaper" when publication of a paper is closed down, and publishers reopen with the same staff and editorial stand but under a new masthead. Examples of such serials that include three or more publications are common. "Serial plaintiffs" are those journalists who are continually charged with defying the law and offending Islam in some way.

Many reformist voices are being actively silenced in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) reports, the reformist point of view can still be heard in Iran , Kar-o KarganAftab-e-YazdNoroozTosseh , Hayat-e No , and Hambasteghi . However, the CPJ also states that many of these newspapers have mellowed in tone. They still argue for reform, but they no longer write about government officials or issues that could be perceived as national security: censorship happens in-house.

State-Press Relations

Mohammed Khatami, a moderate midlevel Shi'a cleric, was reelected president in May 2001. Khatami is a reformist and seeks to offer Iranians more freedom in their daily lives: freedom of association, the press, expression, and so on. However, Supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, a conservative committed to maintaining Islamic traditions and a more closed society, has the authority and opportunity to thwart Khatami's reform efforts, which include a freer press in Iran.

In 2002 the Islamic clerics ruling Iran held power over the media. Part democracy, part theocracy, Iran's Constitution establishes three branches of government, including an elected president and Parliament, and also offers the Supreme Leader, Khamenei, the ability to approve presidential and parliamentary candidates, and make judicial appoints. As a result Khamenei has loaded the courts with conservatives who support his positions.

According to the "World Press Freedom Review," on March 8, 2000, the conservative weekly Harim was banned and accused of mocking and criticizing President Khatami. Khatami, who has no control of the judiciary, pleaded over state radio on March 11 for an open jury trial for the publisher. He stated that if the press is not allowed to operate in Iran, "then people will turn to sources we have no control over."

In June 2002 the CPJ claimed that at least 52 newspapers and magazines have been closed between 1997 and 2001, despite President Khatami's reformist position on the press. These closings include student-run publications as well as licensed commercial publications. CPJ's "Iran Press Freedom Fact Sheet" confirms the following suspensions: 4 in 1998; 5 in 1999; 43 in 2000 (16 between April 23 and 24); and 16 as of September 2001.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

Conservative Iranians are worried that foreign media will destroy the Islamic morals of the population, but reformist Iranians believe the foreign media, free in their home nations, are a vital part of developing democratic social structures.

Foreign correspondents face many of the same problems with censorship, banning, and harassment that Iranian journalists endure. Many foreign journalists have been imprisoned and held incommunicado. The 1997-98 case of an Iranian journalist who resides in Germany, Farah Sarkuhi, illustrates the treatment of all journalists in Iran. Sarkuhi was arrested for "anti-state propaganda," subjected

News Agencies

The Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA), Iran's official news agency, will soon become an independent agency and no longer be state funded. The diverging ideas of the conservative authorities and the IRNA are illustrated in the May 10, 1998, court appearance of IRNA director general, Fereydoun Verdinejad.

Urban newspapers are not well circulated outside the cities, so the provincial readers cannot rely on an Iranian source for information on the county; this has led to a reliance on foreign broadcasts from the BBC, Voice of America, and other Western broadcast sources.

Broadcast Media

According to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), Iran had 72 AM, 5 FM, and 5 short-wave radio stations in 1998. Seventeen million radios were claimed to be in the country as of 1997 estimates, which meant one radio for every 3.8 people. Radio saturation is quite high, as many citizens get their news from this source.

Television's role as a disseminator of news is growing, too. Iran had 28 television broadcast stations, 450 low-power repeaters, and 4.61 million televisions, and there was 1 television for every 14.3 individuals in 1997.

The state controls most radio and television news outlets, and it is often these pro-government voices that disseminate the official hard-line rhetoric.

Electronic News Media

Many newspapers and news sources are available from Iran, and Iranians have tremendous access to information. The Internet is often the only source of information about the country, because newspapers are heavily censored, and the state-run broadcast media is not known for full disclosure. Traditional Islamic clerics are concerned about the Internet and its ability to alter the moral focus of young people and turn them away from Islam.

The Iranian Student News Agency (ISNA) and the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB), which owns several newspapers as well as broadcast media, both had extensive sites on the Internet in June 2002.

Education & TRAINING

The Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA) School of Media Studies provides long-and short-term training for journalists. The university system also offers media and journalism studies.

According to an extensive research study by Dr. Mehdi Mohsenian-Rad and Ali Entezari Rasaneh published in the summer of 1994 in A Research Quarterly of Mass Media Studies , 68 percent of journalists have university educations, but only a small percentage (4.6 percent) have training in communications. Between 1966 and 1994, 900 journalism degrees were awarded in Iran; 93 percent of these graduates do not work in the press. The authors and other experts speculate that the reason for this lack of journalists with journalism degrees, and the small number of those with university journalism training working for the press, is connected to the curriculum presented in the academy. Western media is studied more than Iranian media, and texts are most often translations of Western materials that do not understand the Iranian Islamic culture. In addition, most Iranian journalism curricula focus on newsgathering and interview, and pay little heed to essay writing, editorial work, and analysis.

Summary

The print media feels growing pressure from the use of broadcast and electronic media, especially among the young, those under 30 who represent over 60 percent of the population in 2001. This pressure will continue unless the conservatives are able to limit foreign broadcasting and Internet access in Iran: an unlikely possibility. However, the conflict between reformists seeking more press freedom and the hard-line conservatives is yet to be won by either side, even though the conservative clerics do hold more power and authority in 2002.

Significant Dates

- 1997: Editor dead of multiple stab wounds; Khatami elected in landslide; Sarkuhi arrested, held for closed trial, imprisoned, accused of espionage, tortured, isolated, and abducted.

- 1998: 226 new publications are licensed, bringing the total number of publications to 1,138; circulation increases from 1.5 million in 1997 to 2.9 million.

- July 1999: Student uprising protesting conservative cleric policies and supporting President Khatami's moderate reform.

- April 2000: Ayatollah Ali Khamenei gives speech accusing several papers of "undermining Islamic and revolutionary principles" ("CPJ chronicles"); at least 43 newspapers and magazines shut down.

- March 2001: President Khatami speaks on state-sponsored radio calling for a freer press.

Bibliography

Amnesty International. "Annual Report 2000: Iran," 4 June 2002. Available from http://www.web.amnesty.org .

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). "Iran." CIA Fact-book , 4 June 2002. Available from http://www.cia.gov .

"CPJ chronicles crackdown on Iran's news media," 16 Nov 2001. Available from http://www.freedomforum.org .

Friedman, Thomas L. "Tom's Journal." Public Broadcasting Service, 22 June 2002. Available from http://www.pbs.org .

"Iran: 2001 World Press Freedom Review," 29 May 2002. Available from http://www.freemedia.at .

"Iran's media cuts government links." Asia Times , 17 July 2001. Available from http://www.atimes.com .

Mohsenian-Rad, Dr. Mehdi, and Ali Entezari. "Problems of Journalism Education in Iran." Rasaneh: A Research Quarterly of Mass Media Studies , Summer 1994: 75. Available from http://www.netiran.com .

"Press Law," 22 June 2002. Available from http://www.netiran.com .

Sabra, Hani. "Iran Press Freedom Fact Sheet." Committee to Protect Journalists, 22 June 2002. Available from http://cpj.org .

United States Committee for Refugees. "Country Report: Iran." Worldwide Refugee Information, 6 June 2002. Available from http://www.refugees.org .

World Bank. "Country Overview: Iran," 6 June 2002. Available from http://lnweb18.worldbank.org .

Suzanne Drapeau Morley