Kyrgyzstan

Basic Data

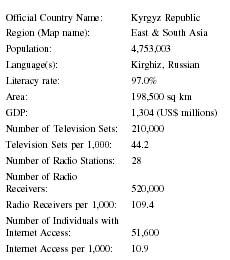

| Official Country Name: | Kyrgyz Republic |

| Region (Map name): | East & South Asia |

| Population: | 4,753,003 |

| Language(s): | Kirghiz, Russian |

| Literacy rate: | 97.0% |

| Area: | 198,500 sq km |

| GDP: | 1,304 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Television Sets: | 210,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 44.2 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 28 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 520,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 109.4 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 51,600 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 10.9 |

Background & General Characteristics

Kyrgyzstan was one of 15 constituent republics of the former Soviet Union that upon the devolution of the Soviet Union became a separate nation. It declared its independence in 1992 and since that time has been pursuing policies aimed at democratic government, decollectivization, privatization, and the change to a market economy. The policies enacted since independence and the relative success of these policies in achieving these goals have been cause for economists and political scientists to judge that the transition in Kyrgyzstan has been among the most successful of all the former republics. However, it is generally agreed that the transition to and relationship with a free and independent media has been the least successful of all its policies. In addition, since the start of the new millennium an even more adversarial relationship with the government has become apparent, to the extent that media relations are now seen by external observers as the most serious impediment to true progress, and indeed is cause for suggesting that many of the gains of the first 10 years of independence are now being seriously eroded. Some observers have suggested that the need for the United States to have a significant presence in the Muslim world following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and in particular the predominantly Muslim Kyrgyzstan, has muted U.S. criticism of Kyrgyzstan government policies toward the media and perhaps encouraged Kyrgyz government attacks on the fledgling independent media.

The legacy of the 70 years of Soviet influence has created a highly educated, highly literate population. In a nation of 4.7 million people there is almost 100 percent literacy (99 percent males, 96 percent females). Most of the population is concentrated in the two large cities of Bishkek (the capital) and Osh, but a significant part of the population resides in smaller urban centers: 38 percent of the population is urban and 62 percent rural. Most of the urban centers have newspapers, and all have television coverage. In the rural areas radio and TV coverage is spotty, in large part due to the mountainous terrain, for much of Kyrgyzstan lies in the northern ranges of the Himalayas. Within the country there are significant ethnic concentrations geographically. The north and rural interior mountain valleys are predominantly populated by ethnic Kyrgyz with concentrations of ethnic Russians in the cities and larger communities. In the south, ethnic Uzbeks are a significant majority, and the media reflect their differing cultural attributes, particularly their Uzbek language. Small concentrations of ethnic Germans, Tatars, Jews, Tadjiks, who are often refugees from war in Afghanistan and Tadkjikistan, are present but are served by the mass media. All ethnic groups except Russians, Germans, and Jews are Muslim.

It is difficult to assess the quality of journalism in Kyrgyzstan for the turmoil over the past 10 years since independence has meant that there has been little history of a consistent regular press, and the turmoil caused by the constant animosity between the press and the government has provided little impartial basis on which to judge. Local westerners rate it a 3 out of 10 and getting worse as a result of the terrible economy, making it difficult for the media outlets to fund quality coverage. Moreover there is a complete lack of historical tradition in journalism, for up to 1990 the Communist government rigidly controlled the press in content and orientation. What can be said was that upon the fall of the Soviet Union there was an immediate and vociferous expression of dissatisfaction that was given voice by the media, and this dissatisfaction has not abated, notwithstanding persistent and punitive actions against the media by the government. In short, 10 years of a free press has been characterized by the voices of dissatisfaction accusing the government of seeking to curtail and control public opinion. The result has been a print media that has focused on providing political commentary to the detriment of providing solid factual news.

Following are the data on newspapers and electronic media in Kyrgyzstan, but what it does not show is the irregular appearance of many of the newspapers on the streets, the complete lack of audited sales (hence the circulation figures are generally unreliable), and the number of newspapers that come into circulation, publish for a short amount of time, and then cease publication without explanation. Most Kyrgyz newspapers are tabloids with 8 to 16 pages per issue. Twelve pages are average. Most are printed overnight and hence are morning editions. Later editions are unknown, and Sunday newspapers are rare. The Friday editions are the largest in volume with 32 pages and also contain the most advertisements, often up to 50 percent, and commanding the highest prices for ads. Otherwise advertising rarely exceeds 20 percent of the content and particularly in those newspapers out of favor with the government, this percentage may be as low as one percent.

Popular magazines (the most popular journal being the AKI Press journal) are available weekly and are dedicated to sports, fashion, film, or automobiles. There are three English language newspapers that come out sporadically and usually cover a week's news. They are the Kyrgyzstan Chronicle , The Times of Central Asia , and the Bishkek Observer . Other language newspapers can occasionally be found in specialized bookstores and kiosks, though invariably the news is dated.

Of the urban centers in Kyrgyzstan, 10 have some form of electronic or print media. The largest and most competitive market is in Bishkek with 18 newspapers, 11 radio stations, and 4 TV stations. The most popular newspaper is Delo Nomar (50,000), followed by Slovo Kyr gyzstana (24,000), Moya Stolitsa (25,000), Aalam (18,000), Res Publica (7,000), Ordo (10,000), Kyrgyz Tuusu (10,000), and Kyrgyz Rukhu (7,000). Vechernyi Bishkek is the largest circulation newspaper with anywhere between 20,000 and 60,000 copies depending on press run, but in view of its government ownership has a dubious claim to being the most popular newspaper. Many other newspapers appear but have limited circulation. For instance Obshestvenniye Rating , Tribuna , and Erkin Too all have circulations of less than 10,000 copies. The cost of a newspaper in 2002 was 3 soms or 0.10 cents U.S. on weekdays and 6 soms on Fridays. The high circulation newspaper Moya Stolitsa has been at the forefront of legal pressure, usually from government ministers for alleged libel. Publication ceased in 2001 as a result of the refusal of the government printing house to print the newspaper, but it has since resumed publication.

Twenty-four other smaller urban centers claim to have newspapers, but it is usually only one local newspaper (though Bishkek newspapers are circulated in these cities). For example the city of Jalalabad, the fourth largest city, has four local newspapers, but they only publish once per week. Similarly a city like Karakol in the mountains of Eastern Kyrgyzstan boasts seven newspapers, but circulation is significantly less than 5,000, and the papers only publish once per week. The exception to this pattern is the city of Osh with 12 newspapers, but none have a circulation larger than 5,000. Similar to Bishkek, Friday and Saturday are the most popular days of publication. In total with a circulation of only 15 per 1,000 people, Kyrgyzstan exhibits one of the lowest newspaper reader-ship levels in the world.

Economic Framework

The economic performance of Kyrgyzstan over the first years of its existence has been rated possibly the best of all former Soviet Central Asian republics. However, while this is cause for optimism in the long term, the performance has been dismal by world standards. Growth rates have been negative or very low; inflation has been as high as 300 percent and in 2002 was still at an unacceptable 37 percent. The result has been low wages, limited foreign investment, and a general moribund economy. Criticism of such a poor economic performance has been limited in the media; rather they have concentrated on the perceived practices of nepotism, cronyism, and corruption that are seen as underlying cases of the poor economic performance. Furthermore the media has spent much time reacting to the autocratic rule of the one man who has held the presidency in the 10 years since the Soviet Union disbanded, President Askar Akaev. Certainly low per capita incomes have limited newspaper purchases, but it would not appear to be a major factor in media success.

The irregular appearance of newspapers on the street and the popularity of television as a medium make television the preferred news source. Newspapers are either government owned ( Vechernyi Bishkek has the government as a majority owner) or privately owned. There are approximately 14 private TV stations and 11 radio stations. In Osh two television stations (Osh Television and Mezon) broadcast in the Uzbek language, and there have been instances when the government has accused the station of both televising too much Uzbek programming and also inciting ethnic hate during elections. It is difficult to classify the types of Kyrgyz newspapers. They are generally popular, but the incessant criticism of government and other entities would suggest that some might be yellow. However, the vicious backlash that has been waged against such journalism is not in keeping with traditions of yellow journalism elsewhere in the world. The small circulations and small staffs have militated against any concentration of ownership in newspaper chains. Competition is ostensibly present, and hence there are no monopolies or the need for antitrust legislation.

The government, through the publishing house Uchkun, owns the distribution network in Kyrgyzstan. Being government-owned, they have few problems obtaining newsprint. The government recently passed a decree (De-cree 20) that gives Uchkun and, by default the government, a monopoly on newsprint allocation, a potentially serious threat to a free press. In addition the government controls the small advertising market and hence has a considerable control over editorial and news content. The average cost of newspaper printing was US$10,500 for 35,000 copies in 2002.

Press Laws

The relationship between the government and the media since the fall of the Soviet Union is the one area that has dominated the emergence and functioning of the press and currently appears to be getting worse rather than better.

The Constitution of the Kyrgyz Republic, adopted in 1993, provides, under Article 16, the rights of all citizens "…to free expression and dissemination of one's thoughts, ideas, opinions, freedom of literary, artistic, scientific and technical creative work, freedom of the press, transmission and dissemination of information." Two supplementary laws that govern the media were passed in 1997: "On guarantees and free access to information" and "On the protection of professional activities of Journalists." "The Law of the Kyrgyz Republic on Mass Media" was originally passed in 1992, and despite pressure to amend this law, it remains in place as the most important law governing the media. There are no freedom of information laws in Kyrgyzstan.

As a requirement of that statute all of the country's mass media, including media owners and journalists, must register with the Ministry of Justice in the case of print, or the National Agency for Communications in the case of electronic media and cannot work or publish until permission has been granted by the Ministry. Permission is usually forthcoming in the one-month period required for a decision. The National Agency for Communications also reviews program schedules and issues electronic frequencies for broadcasting. In some cases the agency has unilaterally required stations to change frequencies thus incurring significant disruption and cost to the station. As a result of these restrictions Radio Free Europe estimates only two radio stations in the country are broadcasting legally. There is a fee for registration, but posted bonds are not required.

The press laws establish quite clearly what is prohibited material, namely official state secrets, intolerance toward ethnic minorities, pornography, and desecration of Kyrgyz national symbols like the national seal, anthem, or flag. The statute also identifies "encroachment on the honor and dignity of the person" as an offense. The statute (Articles 24-28) takes great care to identify indemnity of moral damage and other offences of this kind, and it is these provisions in the law that have been extensively used to stymie and restrict the media. Furthermore libel is a criminal, not a civil, action, and attempts to change this have been overwhelmingly defeated in the national Parliament with little hope given for this status to change. The result has been imprisonment of journalists, heavy fines, and ultimately media cessation of publication. It is this situation and the lack of an incentive to change that suggests an unfavorable prognosis for improvement. In the application of these press laws the judiciary has generally been favorable to the plaintiff in the case of honor and dignity suits launched against the media. This might be expected insomuch as the president and Parliament appoint the judiciary.

State-Press Relations

The right to free speech and freedom of the press, while enshrined in the Constitution and the media laws, is in practice generally not respected. Moreover, legislation that would further restrict the media seems to be an ongoing threat.

The state controls the television and much of the radio, and these outlets receive significant subsidies, which permit the government to influence the media. While the power of the government to affect and in some cases silence media agents has been clearly shown (many of whom were imprisoned, fled, or faced trial on flimsy charges), it might be suggested that in lieu of a strong vocal opposition to the president, the fact that there is independent media who still voice opposition and protest suggests that there may be hope for some form of editorial influence on government policies.

In an attempt to break the stranglehold on the printing and distribution of the print media by Uchkun, the European Union attempted in 2002 to sponsor the import of new printing presses. To date the government has withheld an import license for the equipment, and hence alternative presses for newspaper publishing are not available. Ironically, while the former Soviet Union promoted a strong and vociferous trade union movement, in the years since independence no form of worker protest against media manipulation has occurred.

Censorship

There is no single agency in Kyrgyzstan concerned with monitoring the press, but the fact that Uchkun is the only newspaper-publishing house in the country and that it is government owned creates a de facto censorship. For example, Uchkun refused to publish Res Publica (pending payment of a fine to the president of the state TV and corporation) in 2000, and in 2002 it was refusing to print both Res Publica and Moya Stolitsa-Novosti (notwith-standing court orders to publish the newspapers) over alleged "moral damage" to the president of Uchkun. In view of the possibility of jail and the heavy fines that have been levied against journalists and independent newspaper owners, it is generally agreed that self-censorship is a significant occurrence in Kyrgyzstan. For example, one journalist in Jalalabad was sentenced to two years in prison and a fine equivalent to US$2,250—both penalties were subsequently reduced on appeal. In 2001 Res Publica was fined an equivalent of US$5,000 for criticizing the justice department, and the independent newspaper Asaba was required to pay the equivalent of US$105,000 to a parliamentary deputy for repeated insults over an eight-year period. The challenge, as one observer put it, is "to stay out of jail but publish something that has some relation to the truth." In what may be seen as a response to the increasing pressure on the media from government, there has been a significant increase in the number of agencies, foundations, and associations both internally and externally created. Most important is the Public Association of Journalists, a media non-government organization or NGO, "Glasnost (openness) Defense" Public Foundation to defend journalists in court (established in 1999); the public association "Journalists" representing 160 media professionals in the republic (founded in 1998); the Public Foundation of Media Development and the Protection of Journalists' Rights (founded in 1998); and the "Press Club" founded in 2000. The Association of Independent Electronic Mass Media of Central Asia, "Anesmi," (founded in 1995) represents the electronic media but is for all practical purposes defunct. There is also a Center of Women Journalists of Central Asia, as there are a large number of female journalists in Kyrgyzstan, where gender issues are increasingly coming to the fore in this predominantly Islamic country. Journalists can also be part of the Union of Journalists of the Kyrgyz Republic. In Osh the Resource Media Center has been active in the fight for journalists' rights. Sadly there is no Press Council that mediates disputes between plaintiffs and the media in the event of perceived slights; rather litigation is the preferred means of dispute resolution.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

Article 30 of the state media law guarantees the right of foreign mass media to operate in Kyrgyzstan without opposition. Generally the government's attitude toward foreign media has been one of dislike as a result of the criticism that has been directed toward Kyrgyzstan's record on media freedoms. There have been instances of foreign journalists being assaulted—in 2002 a journalist from the Kyrgyz-Turkish newspaper Zaman Kyrgyzstan was assaulted, but whether this was directed against him as a representative of the media or just unrelated street crime cannot be ascertained. More significantly western governments, particularly the United States and UNESCO, have played a major role in the protection and education of journalists in order to stimulate an independent media. UNESCO has established a Media Resource Center in Bishkek to which journalists from Europe and the America's come to instruct others in the best practices for journalists. English language classes and computer literacy classes have also been taught. In the future management courses will be taught. Of more direct impact has been the establishment, as a result of U.S. State Department funding, of Internews. Internews is a nongovernmental organization (NGO) that operates "based on the conviction that vigorous and diverse mass media form an essential cornerstone to an open society." To that end it produces TV news programs and youth radio stations but more recently has become involved in the defense of TV stations, radio stations, and journalists who have been sued under the nation's media laws. Internews is also active in the proposed amendment of current media laws. Foreign correspondents do not have to be accredited, nor do they require special visas. Cables are not approved, nor have there been any instances of foreign correspondents being prevented from doing their job. Domestic journalists have free access to international press organizations. The Kyrgyz government tacitly supports the UNESCO Declaration of 1979 by its support of the OSCE office in Bishkek that monitors this declaration.

News Agencies

The official government news agency is named Kabar. It is responsible for all government pronouncements and is the best source for local news but is generally considered untrustworthy. Western NGOs and other

Broadcast Media

The state owns and controls the TV station transmitters and therefore is in a position to control electronic news broadcasts. There are five TV channels in the capital city of Bishkek. Channel one is Kyrgyz programming, channels two and three are feeds from Moscow, channel four is a Turkish feed, and channel five is the independent channel showing mostly soap operas and pirated western movies.

Electronic News Media

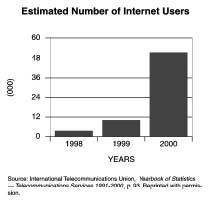

The importance of the Internet as a source of information is limited owing to the lack of computers and the poor telecommunications network in the country. In an attempt to expand the Internet as a news source, the U.S. State Department opened seven information centers in seven cities and towns with free access to the Internet to enable citizens to access various press sites. In 2003 it will open five more urban centers. In yet another example of a contradiction between theory and practice, the government has undertaken to increase electronic access and communication, while shutting down the online news site "Politica KG" in 2000 during the presidential election.

Education & TRAINING

There are a number of schools of journalism in Kyrgyzstan institutes of higher education. The primary institutions teaching journalism are the American University in Kyrgyzstan (AUK), Slavic University, and Bishkek Humanities University. Many Kyrgyz students in standard literature classes also see journalism as a viable and attractive career. The numbers graduating from these institutions are small. For example, AUK graduated 10 journalism students in 2001.

Summary

The most serious problem facing the provision of an independent media in Kyrgyzstan is the attitude and policies of the government. In the earliest years of independence there was cause for hope that the media would grow to become a solid acceptable force in the progress of the nation. By the late 1990s the situation had begun to deteriorate with a significant growth in the number of lawsuits, harassment of journalists by means of intimidation, and use of the taxation system to challenge the existence of an independent media. Matters came to a head in 2000 when the president, Askar Akaev, sought a third term in office, normally prohibited under the Constitution but permitted by the Supreme Court on the basis that he became president under the old Soviet regime and hence technically had not served two terms. The media outcry was met by a series of punitive measures against any of the media that opposed his campaign for a third term. Thus the situation exists in the early twenty-first century where, on a scale of one to one hundred (Free= 0-30, partly free= 31-60, and Not free 61-100), the 1999 Freedom House Survey of Press Freedom rated Kyrgyzstan 64 and is considered without a free press, a situation reminiscent of the press under the Soviet regime only 10 years earlier.

The prospects and prognosis for the media in the twenty-first century is dependent on the state of relations with the government. Certainly the government in its official statements espouses the need for a free and independent media, but in practice it is a long way from that reality. From here the government can go even further in its challenge to the independence of the media, secure in the knowledge that for the foreseeable future western governments need to be on good terms with Islamic governments. Or it can address the concerns voiced by both the OSCE and the U.S. government that human rights and the state of the mass media are areas of immediate and serious concern and can address these issues to the satisfaction of Kyrgyz journalists, media, and outside observers.

Bibliography

Freedom House Media Ratings, 2002. Available from http://freedomhouse.org .

Kyrgyzstan 2001 World Press Freedom Review . Available from http://freemedia.at .

U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). "Report on Independent Media," 2002. Available from http://www.usaid.gov .

U.S. Department of State. "Country Reports on Human Rights Practices 2001." Available from http://www.state.gov .

Richard W. Benfield

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: