Morocco

Basic Data

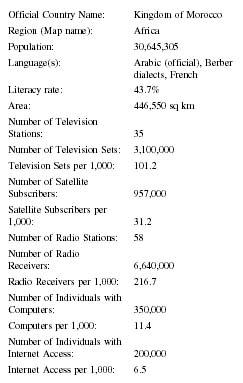

| Official Country Name: | Kingdom of Morocco |

| Region (Map name): | Africa |

| Population: | 30,645,305 |

| Language(s): | Arabic (official), Berber dialects, French |

| Literacy rate: | 43.7% |

| Area: | 446,550 sq km |

| Number of Television Stations: | 35 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 3,100,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 101.2 |

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 957,000 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 31.2 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 58 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 6,640,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 216.7 |

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 350,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 11.4 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 200,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 6.5 |

Background & General Characteristics

Between 1912 and 1956 Morocco was a protectorate within the French colonial empire of North Africa. After it won its independence, the kingdom of Morocco was left with a deeply rooted French cultural influence that went on to provide much of the framework for its judicial, political, and educational systems. Morocco also inherited a press formed and nurtured by French journalistic traditions. Historically, French newspapers reflect particular political viewpoints and social agendas. Rather than striving for factual and unbiased news reporting, they are essentially the journalistic expression of a given political ideology. Moroccan newspapers have continued this tradition and today provide their readers a steady flow of editorialized news. Each newspaper, whether nationally prominent or printing only a few thousand copies, reflects a given political tendency, encompassing varied political viewpoints from monarchist to communist. Morocco has also perpetuated a French concept of the freedom of the press, born out of the authoritarian regimes of the nineteenth century. Thus, the Moroccan government accepts mild forms of political criticism but tolerates no attack on the monarchy or Islam. Journalists and newspaper editors are considered professionals who must report the news, but they are also considered educated, patriotic citizens who should be mindful of their social responsibilities to the public. If newspapers in Morocco expect to remain in business, they must agree to exercise some form of restraint and to practice self-censorship. To guarantee that criticism of official policies remains within appropriate boundaries, the government grants a subsidy of 50 million dirhams to the press (approximately US$6 million) each year. Since advertising revenues and newsstand sales represent only a slim portion of the operating budget of most Moroccan newspapers, the yearly government subsidy provides an effective means to prevent the Moroccan press from operating with full autonomy.

Like other former French colonies of North Africa, Morocco enjoys the diversity of a bilingual press. Newspapers are published either in French or Arabic. Even after the country gained its independence in 1956, French was still used by the upper echelon of Moroccan society, while Arabic remained the spoken language of the masses. Since the 1970s, however, Arabic has gained a considerable popularity and Arabic-language newspapers have flourished, as Morocco underwent a process of reclaiming its cultural heritage. Today, French is still the language of the cultural elite in Morocco. It is the language of private schools, diplomats, and educated professionals, but Arabic newspapers now represent the majority of the Moroccan press. In 1983 the French-language newspaper Le Matin enjoyed the largest circulation of all Moroccan dailies, with 50,000 copies. That privilege belonged in 2002 to the Arabic-language newspaper Al Ittahid Al Ichtiraki, with a daily circulation of 110,000. In that year, Arabic dailies attracted a readership in excess of 260,000, while French-language newspapers reached about 200,000 people.

With a population of 30,645,395 (2002), a GDP of $108 billion, and a literacy rate of only 44 percent, Morocco publishes 22 major daily newspapers, with an aggregate circulation of 704,000 (circulation per thousand: 27.) The press consumes 19,000 metric tons of newsprint annually. Many new dailies have appeared since 1990, and their number continues to increase. Old vanguards of the past, such as the longest-running French language daily Maroc-Soir (established in 1908) and the promonarchist Arabic language newspaper Al Mithaq Al Watani (established in 1977), have disappeared. The most influential newspapers are published either in Rabat (the capital) or in Casablanca. In addition to the major national newspapers, Morocco also published a total of 644 dailies and weekly papers in 2001 (430 in Arabic, 199 in French, 8 in the Berber dialect, 6 in English, and 1 in Spanish) and over 700 periodicals with an aggregate circulation of 3,671,000.

In terms of circulation, the largest Moroccan daily newspapers were in 2001:

- Al Ittihad Al Ichtiraki (1983), socialist, published in Arabic, circulation: 110,000.

- Le Matin du Sahara et du Maghreb (1972), royalist, in French, circulation: 100,000.

- Al Alam (1946), published by the pro-government Istiqlal party, in Arabic, circulation: 100,000.

- L'Opinion (1965), published by the pro-government Istiqlal party, in French, circulation: 60,000.

- Libé ration (1964), democratic left, in French, circulation: 20,000.

- Al Anbaa (1963), official publication of the Moroccan Ministry of Information, in Arabic, circulation: 15,000.

- Al Bayane (1971), communist, in French, circulation: 5,000.

Among the most popular periodicals are Maroc Hebdo International (French), Al Mouatine Assiyassi (Arabic), l'Economiste (French), Al Ayam (Arabic), and Jeune Afrique (published in France).

Economic Framework

In the past the majority of Moroccan newspapers did not represent actual commercial ventures or profit-making corporations, since they were essentially the written public outlet of political parties. As such they were owned by political interests and survived on contributions and government subsidies. In the last 10 years an influx of new capital has led to the creation of newspapers and periodicals that aspire to become commercially profitable. It should be noted, however, that the new publications are still heavily dependent on the government's budgetary allocations and that this reliance is inversely proportional to the professional autonomy of the younger generation of journalists. Out of the seven major Moroccan daily newspapers, four are pro-government (including one overtly royalist), two are issued by the Istiqlal coalition party, and another is published by the Moroccan Ministry of Information. The other three are in the opposition (center-left, socialist, and communist), but even that definition does not fully represent an independent political alternative. The new Moroccan prime minister is Abderrahamane Youssefi, who was once a left-wing activist, and a coalition of liberal royalist ideas and socialist tendencies seems to be the new political reality. The openly communist daily Al Bayane , a few far-left weeklies, and hard-line Islamic fundamentalist periodicals are the only means of true criticism in the Moroccan press. However, they are regularly harassed by the authorities, and their readership is quite limited. In terms of circulation, the pro-government dailies represent 75 percent of all major Moroccan newspapers, while the socialist, Arabic-language daily Al Ittihad Al Ichtiraki remains the most widely read paper in Morocco, with a circulation of 110,000.

Press Laws

The Moroccan press faces a double challenge when it seeks to operate within contemporary western standards of the freedom of the press. Political traditions inherited from the French and the authoritarianism of the monarchy have created a legal framework that allows the government to restrict the flow of information. Newspapers can be fined, suspended, or banned, and a journal-ist's freedom of expression limited for the purpose of guaranteeing social order or insuring national security. Morocco is a monarchy with a king possessing real and unchecked executive powers, and such a political construct is not easily compatible with the criticism and scrutiny of a free press. King Mohammed V instituted the first national press code in 1963 on the framework of the previous laws that had been in force under the French protectorate between 1912 and 1956. The code was later strengthened under his successor, King Hassan II. In 1999 the accession to the throne of his liberal-minded son, King Mohammed VI, had raised the hope of a radical reform of Moroccan press laws, but such aspirations have not been fully realized. The Parliamentary Commission for Foreign Affairs and National Defense adopted a new national press code on February 8, 2002. Somewhat more lenient than its predecessor (it contains fewer criminal penalties for libel), the code still maintains sentences of three to five years imprisonment for defaming the king or the royal family (as compared with five to twenty years imprisonment in the previous code.) Article 29 also gives the government the right to shut down any publication "prejudicial to Islam, the monarchy, territorial integrity, or public order." Moroccan officials maintain that the kingdom enjoys a freedom of the press unparalleled in other Arab nations in the region. It is a fact that Morocco has never silenced political criticism in the press with the ruthlessness and violence evidenced in Algeria or the Sudan. King Mohammed VI and his ministers find themselves in the awkward position of moving Morocco into the twenty-first century, of being politically pro-western while exemplifying the values of a moderate Islamic nation. As the king declared in an interview he granted to Al Sharq Al Awsat in July 2001: "Of course I am for press freedom, but I would like that freedom to be responsible….I personally appreciate the critical role that the press and Moroccan journalists play in public debate, but we need to be careful not to give in to the temptation of the imported model. The risk is seeing our own values alienated…. There are limits set by the law."

Censorship

Mindful of the increasing popularity of Islamic fundamentalism in the poorer sectors of the country (20 percent of the population lives under the poverty level), Morocco is trying to build a modern economy that could lift it out of chronic stagnation. It must also avoid the risk of antagonizing conservative clerics and activists who do not share the elite's predilection for western values. The press is expected to exercise restraint and self-control when dealing with criticism of official government policies. According to Reporters Without Borders and the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), two international organizations dedicated to the protection of journalists' freedom of expression throughout the world, the actions of Moroccan officials against freedom of the press have increased in their severity since 2000. In its "Middle East and North Africa Report," the CPJ indicates that three Moroccan weekly newspapers, Le Journal, Al Sahiffa , and Demain were permanently banned by the government in December 2000. They had published articles questioning Morocco's military activities in a disputed part of the Western Sahara and had investigated the possible involvement of Prime Minister Youssefi in a plot to assassinate the late King Hassan II in 1972. In April 2000 the editors of Al Ousbou and Al Shamal were sentenced to jail, ordered to pay fines, and banned from journalism for three years for investigative articles published on Moroccan Foreign Minister Muhammed Ben Aissa. Reporters Without Borders also reports than in 2001 the managing editor of Le Journal Hebdomadaire was sentenced to three months in jail and ordered to pay a fine of $200,000 for publishing a series of articles on the same foreign minister. These articles investigated allegations that the foreign minister misappropriated public funds while serving as ambassador to the United States.

State-Press Relations

In Morocco, state-press relations constitute a mutually grating and benefiting tug of war. The government supports the press with generous yearly subsidies, but it expects all journalists and editors to exercise restraint and to refrain from any negative criticism of the royal family, official state policies, or Islam. Investigative reporting is discouraged and most newspapers comply with the state's wishes by not addressing sensitive issues. In 2001 the Moroccan Ministry of Information allotted 20 million dirhams to be distributed among the major national newspapers. It also contributed ten million dirhams for the purchase of printing paper and international phone and fax bills. It paid another 10 million dirhams for the publication of legal and official announcements and an additional 10 million for various press-related expenses. The total budgeted amount for 2001 exceeded 50 million dirhams (US$6 million). Traditionally, that money is given for the encouragement and promotion of an independent press with high professional standards. By western standards, however, the very existence of such subsidies is difficult to reconcile with the establishment of an autonomous press. The Moroccan government also exerts another measure of control on the press by requiring every journalist, editor, or foreign correspondent to qualify for an official press card. The number of these cards has increased from 921 in 1992 to 1,097 in 1999.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

French newspapers and periodicals still attract a large number of readers in Morocco. Major Parisian newspapers, such as Le Figaro and Le Monde , are widely read among Moroccan professionals. English, Spanish, and American publications are also available, and they provide a welcome (if at times censored) source of alternate information, especially for sensitive or potentially damaging information dealing with Moroccan foreign policy or the royal family. The U.S. press, however, is largely seen among younger professionals and English-speaking students as presenting a unilateral, capitalistic, and pro-Israeli point of view. When searching foreign media for news dealing with the Arab world, Moroccan intellectuals are more likely to turn to French newspapers and periodicals, since the majority of French media is traditionally pro-Palestinian. American newspapers are often distrusted and suspected of being controlled by Jewish interests.

The success of the foreign press in offering Moroccan readers stimulating investigative reporting is illustrated by the vehemence of censorship and harassment it endures on a regular basis. In 2001 alone, the Spanish newspapers El País (7/22) and El Mundo (9/6), the Spanish weeklies Cambio (3/19) and Hola (11/23), the French daily Le Figaro (3/4) (7/5), and the French weeklies Le Canard Enchainé (10/31), VDS (3/7), Jeune Afrique (3/15), and Courrier International (5/17) were intercepted, blocked, seized, or otherwise removed from the newsstands by the Moroccan police. On November 4, 2001, Claude Juvénal, the Rabat bureau chief of Agence France-Presse (AFP), was ordered to leave the country

News Agencies

The Associated Press (AP) and Agence France-Presse (AFP) maintain active accredited bureaus throughout Morocco. The Maghreb Arab Press Agency (MAP), inaugurated in 1977, has become one of the largest news agencies in the Arab world. A state-owned corporation, it is headquartered in Rabat and has 10 regional and 17 international offices.

Electronic News Media

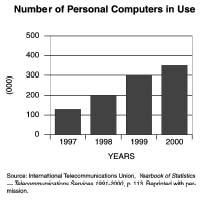

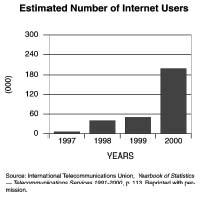

The development of the Internet has brought a new dimension to news reporting in Morocco. Many of the major dailies and weeklies can now be accessed on their own Web sites. The number of Internet users has dramatically increased to over 120,000 in 2002, with eight Internet Service Providers (ISP) in operation. In 1996 the government created Mincom Ilaycom , a large official Web site with a search engine, for the purpose of disseminating official information about Morocco ( www.mincom.gov.ma ). It was followed by the launching of Marweb.com , another search engine and reference data bank particularly useful for its weekly review of the Moroccan press. In 2001 Morocco had 1,425,000 telephones (including 116,645 cell phones,) 27 AM and 25 FM radio stations (with 6.65 million sets), and 35 TV stations with 3.1 million TV sets. Satellite relays, optical cables, dish systems, and digital equipment now bring Arab, European, and American television programming into every region of the country.

Education & TRAINING

Moroccan journalists are trained at the Higher Institute of Journalism, established in 1980, which operates an influential alumni association (the ALISJ), and at the Higher Institute of Information and Communication (ISIC), established in 1996. Several professional press organizations also play an important role in setting standards and defending their members' rights: the National Union of the Moroccan Press (SNPM), established in 1963, which receives an annual government subsidy of 200,000 dirhams, the Moroccan branch of the International Union of French-Speaking Journalists (UJIPLF) and the Press Club, established in 1992, which also receives an official yearly subsidy of 200,000 dirhams.

Summary

The Moroccan press faces the challenges and the hopes that are common to developing North African nations. The press and the government are locked in a mutually dependent relationship that creates both encouraging opportunities and disturbing issues involving a journal-ist's need to report the news in an impartial and unhindered manner. The Moroccan press is growing and has made great strides since the 1960s toward achieving its autonomy. The government keeps controlling the press via generous subsidies and repeated censorship. It fosters a climate of subtle intimidation that seriously impairs Moroccan newspapers and periodicals from openly questioning government policies and established societal traditions. Morocco justifies this attitude by maintaining that it must moderately muzzle the press if it ever hopes to succeed as a pro-western, moderate Islamic nation in a region of the world where fanaticism is a constant menace to civil liberties.

Bibliography

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). 2001 World Factbook . Directorate of Intelligence, 2002. Available from http://www.cia.gov/ .

Committee to Protect Journalists. Available from http://www.cpj.org/ .

The Editor and Publisher International Yearbook . 81st edition. 2001.

Kingdom of Morocco . Available from http://www.mincom.gov.ma

Marweb.com . Available from http://www.marweb.com/ .

Mohamed El Kobbi, L'Etat et la Presse au Maroc . Paris: L'auteur, 1992.

Mohammed Rhazi, Introduction á l'Etude de la Presse au Maroc , Dissertation: Université de Paris II. 1981.

Organisation Marocaine des Droits de l'Homme, Liberté de la Presse et de l'Information au Maroc: Limites et Perspectives. Rabat: OMDH, 1995.

Reporters without Borders. Available from http://www.rsf.org

UNESCO Statistical Yearbook, 1999

Eric H. du Plessis