Nepal

Basic Data

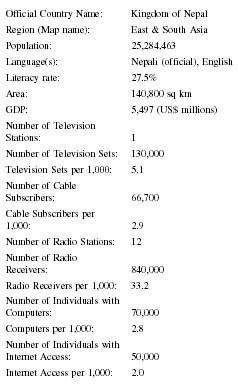

| Official Country Name: | Kingdom of Nepal |

| Region (Map name): | East & South Asia |

| Population: | 25,284,463 |

| Language(s): | Nepali (official), English |

| Literacy rate: | 27.5% |

| Area: | 140,800 sq km |

| GDP: | 5,497 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Television Stations: | 1 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 130,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 5.1 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 66,700 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 2.9 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 12 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 840,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 33.2 |

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 70,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 2.8 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 50,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 2.0 |

Background & General Characteristics

The Nepalese government rigidly controls the press. Laws regulate press activity and copyright stipulations, which are specific to the kingdom of Nepal because it did not sign the international Berne Convention regarding copyright. By the twenty-first century, Nepal had 2048 Constitutional provisions dictating how the press should publish news and information. Media often presents conflicting perspectives because of the varied policies and agendas constraining journalists.

In the early twenty-first century, the Department of Information said that Nepal has approximately 1,550 news publications of which 185 are published on a regular basis. Half of the publications are based in Kathmandu. Approximately 60 daily newspapers are published in Nepal; about 80 percent of Nepalese newspapers are weeklies. The Rastriya Samachar Samiti (RSS) National News Agency posts a reporter in each of Nepal's seventy-five districts in addition to a main office in Kathmandu and releases mostly government speeches. Two-thirds of the districts of the kingdom have newspapers and journals, which have low circulation rates. Although 85 percent of Nepalis live in rural areas, most mainstream Nepalese media published in the Kathmandu Valley ignores issues specific to those areas. Fifty-five percent of Nepal's 24 million population are illiterate, and poor roads and infrastructure limit print media distribution.

In 1898, Sudhasagar was the first newspaper published in Nepal. Gorkhapatra (Nepalese), published in Kathmandu since 1901, is Nepal's oldest newspaper still in circulation. Founder Maharaja Dev Shamsher Rana intended this newspaper to voice the Nepalese people's opinions and concerns. Instead, this government-owned periodical prints mostly speech texts and official pronouncements. Gorkhapatra became a daily in 1960 and had the largest circulation in Nepal with an estimated 75,000 copies. The language used in this newspaper is a complex version of Nepalese that is often difficult even for natives to comprehend. The contents of Gorkhapatra are similar to Rising Nepal , an English daily published by the government's Gorkhapatra Corporation that is intended for a tourist and expatriate readership. A Nepalese edition of Rising Nepal is also issued. Some news obtained from foreign press agencies is translated into Nepalese.

The Nepal media frequently features the royal family and palace events. King Birenda contributed a daily saying for editorial pages. Attempts to privatize the Gorkhapatra Publication Corporation have been unsuccessful. In the early 1980s, journalists became more vocal against government involvement with the media. Keshab Raj Pindali founded the influential independent Saptahik Bi-marsha (Weekly Review) in 1982. Prime Minister Surya Bahadur Thapa provided funds for Nepalese Awaj (Nepalese Voice) but did not force that newspaper to endorse only his liberal agenda. Nepalese Awaj advocated establishment of a multi-party government and denounced the politically corrupt bhumigat giroh (underground gang). After the April 1990 pro-democracy revolution, Rising Nepal and other newspapers began carrying news about the new political parties permitted to function in Nepal. Founded in 1993 as the first private morning daily, Kantipur newspaper had the largest circulation by the twenty-first century.

Many Nepalese magazines are printed in English. The Nepal Traveler is designed for distribution to tourists, hotels, and airports and features cultural stories such as events related to festivals and holidays. The weekly Nepal Press Digest was first published in Kathmandu in 1956 and prints news from foreign newspapers as well as political parties' information which official government papers either refuse to include or discuss with bias. Himal is a bimonthly prepared by the Kathmandu Himal Associates since 1988 that includes environmental essays, book reviews, and news concerning the region around the Himalayas. Alternative media includes Asmita Monthly , a feminist magazine published since 1989 with a circulation of 10,000 and an estimated readership ten times that number, which explores gender and human rights issues and promotes social responsibility.

Press Laws

In 1960, after King Mahendra Bir Bikram overthrew Nepal's parliamentary government and established the non-political party system Panchayat, media conformity was demanded by the dictatorial monarchy. The 1962 RSS Act specified that only the government news agency could exist. The Press and Publication Act of 1965 stated in section 30 that the government could order cessation of media considered harmful to public interests. A Press Advisory Council was established in 1967 as a means to ease relations with frustrated media professionals, but journalists had minimal input. Four years later, the National Communication Plan encouraged improvements of government-sanctioned media for Nepal's development. The government envisioned using radio to educate rural teachers. In 1975, a second Press and Publication Act forbade criticism of Nepalese royalty and government.

King Birenda Bir Bikram perpetuated his father's press policies until the 1990 democratic revolution, which the private press supported. The ban on political parties was lifted, and a multiparty coalition government was developed. The next year, the Nepalese Congress party won the first democratic election held in thirty-two years. This democratic revolution reduced some of the strict media controls because the new constitution addressed the right to distribute information. However, journalists were still controlled if they attempted to investigate and report on issues the government considered controversial.

State-Press Relations

Each publication or station in Nepal presents accounts based on their political affiliations. Ninety percent of Nepalese newspapers do not sell advertisements and rely on sponsors, usually politically related. Journalists often are active members of political parties and use the media to advance their political careers. Many editors and publishers gain their positions through political appointments and lack journalistic education and experience. As a result, reports tend to favor partisan agendas.

Representatives of independent media are usually unable to convince political parties to share news with them. Reporters risk losing their jobs if they attempt to write or broadcast pieces contrary to government media dictates. Nepal's constitution includes the right for Nepalis to have access to information, but the Nepalese government resists cooperating with independent media and risking the release of news which might be embarrassing for officials. The lack of credibility of many journalists causes Nepalis to be skeptical about news.

Reporters often describe journalism as one of Nepal's most dangerous professions. Many Nepalese journalists are afraid to report accurately about government corruption, especially concerning judiciary or police abuse of power, because they might be arrested and charged with contempt of court. Targeted journalists often have their offices raided or homes ransacked. In 1994, Harihar Birahi, editor of the weekly Bimarsha Nepalese , was fined and jailed for printing a cartoon depiction of Nepal's Supreme Court. Journalists Mathbar Singh Basnet and Sarachchandra Osti published a photograph of Princess Shruti Shah posed with an Indian actor in the weekly Punarjagaran Nepalese and were punished for implied criticism of the royal family. Om Sharma was imprisoned for 89 days in 1997 without a trial on charges that he had supported Maoist guerillas.

On June 7, 2001, the Kathmandu Post reported that the government had arrested Kantipur 's editor Yubaraj Ghimire and Kantipur Publications directors Kailash Sirohiya and Binod Raj Gyawali. The police officers claimed the journalists were guilty of printing rebel Maoist leader Dr. Baburam Bhattarai's editorial, which blamed a conspiracy for the June 1, 2001, massacre of King Birendra and his family. High-ranking Nepal authorities refused to answer reporters' questions concerning the charges. The Nepalese government had previously monitored the Kantipur Publications' investigative reports that focused on government corruption and scandals. Reporters speculated that media scrutiny and criticism had enraged government officials such as Prime Minister Girija Prasad Koirala who wanted to eliminate any freedom of the press. Both the Federation of Nepal Journalists Association and the Working Journalists' Association protested the arrest and noted that Nepalese journalists had long resisted efforts to silence media and resented psychological techniques intended to intimidate reporters, editors, and publishers. The groups also criticized the government for not publicizing facts about the royal killings. Nepalese and international media, human rights groups, and diplomats denounced the arrests and demanded that the prisoners be released. Former Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba supported the media and stressed that freedom of the press was essential for democracy to thrive.

Minister for Information and Communication Shiva Raj Joshi justified the government's actions for intervening as reaction to anti-monarchy essays. At a press conference, Nepal officials requested that the media refrain from issuing material that might instigate national disunity and damage the government's integrity. The government established a branch for information to transmit approved news releases about the palace massacre to the media. Minister of State for Information and Communication, Puskar Nath Ojha urged the press to not antagonize the government.

Broadcast Media

Most Nepalese have access to information via radio. Established in 1950, the state-owned Radio Nepal broadcasts to all of Nepal except the Himalayas. The Radio Nepal meeting hall is the occasional site of government press conferences. The 1993 Communication Policy Act encouraged independent radio transmissions. By 1995, Radio Nepal began selling airtime to private investors for commercial broadcasts. Three years later, the government began issuing licenses to private FM radio stations. Approximately one dozen stations have been licensed, but they are not permitted to air news and political bulletins. Most stations are concentrated in the Kathmandu Valley, but some are located in other parts of Nepal. Radio Sagarmatha, established in 1998, was the first independent FM station, and operates from the base of Mount Everest. The BBC Nepalese Service has broadcast since 1994.

Beginning in December 1985, the state-owned Nepal Television Corporation began airing programs several hours daily. By the twenty-first century, there were 79,000 televisions in Nepal. Viewers often use satellite dishes to receive international broadcasts from CNN and the BBC in addition to Indian and foreign programs. Television is limited because only 15 percent of homes have electricity. Much broadcast media consists of entertainment rather than news.

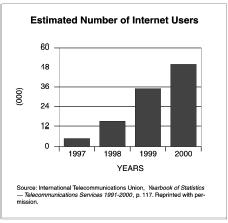

Internet access is Nepal is limited by lack of equipment and related expenses. Journalists do not regularly use the Internet to research. Some sites post articles from

Education & Training

Some Nepalese journalists are educated at foreign universities because of limited opportunities in Nepal. Journalism courses are offered at Tribhuvan and Purvanchal Universities, which have limited media equipment. The Nepal Association of Media Educators aspires to develop graduate programs for journalists to earn master's degrees in mass communication at Nepalese colleges. Reporters can also train at the Nepal Press Institute or Media Point, a journalism center in Kathmandu.

Professional media organizations include the Nepal Press Union, Journalism Research and Training Society of Nepal, and Nepal Forum of Environmental Journalists. Those groups present seminars and workshops to encourage professionalism and sponsor investigative journalism competitions.

Bibliography

Amatya, Purna P. Cumulative Index to Selected Nepalese Journals. Kathmandu: Centre for Nepal and Asian Studies, 1989.

Baral, Lok Raj. "The Press in Nepal, 1951-1974." Contributions to Nepalese Studies , 2. (February 1975): 169-186.

Belknap, Bruce J. A Selected Index of Articles from The Rising Nepal from 1969-1976 . Kathmandu: Doumentation Centre, Centre for Nepal and Asian Studies, 1978.

Karmacharya, Madhav Lal. The Publishing World in Nepal . Kathmandu: Laligurans, 1985.

Kharel, P., ed. Media Nepal 2000 . Kathmandu: Nepal Press Institute, 2000.

—— ed. Media Practices in Nepal . Kathmandu: Published by Nepal Press Institute with the support of DANIDA, 2001.

Malla, B.C. "Mass-media, Tradition and Change (an Overview of Change in Nepal)." Contributions to Nepalese Studies , vol. 10, nos. 1-2 (December 1982/June 1983): 69-79.

Pokhrel, Gokul Prasad, and Bharat Dutta Koirala, compilers. Mass Media Laws and Regulations in Nepal . Kathmandu: Nepal Press Institute, and Asian Mass Communication Research and Information Centre, Singapore, 1995.

Elizabeth D. Schafer

I'm looking to sponsor an annual award for news articles/photos showing the issues impacting youth.

This article gives me some options.

There are people who received millions of dollar in the past decade collecting grants from large donors including Gates foundation with utter failure to fulfill as the end result.

Who will govern? who are they accountable to using country's name and people?

A typical case e.g. is Stonestep who received millions of dollar from various donor agents including Sakcham in Nepal two years ago and yet to deliver any? There's no achievement reports are published, no baseline study was conducted, no social audit reports were published with any impacts or indications.

Who will control these Wolves in sheep-cloths?

Should the people of Nepal allow such person-interest business people abuse the plights of these people to make money for themselves?

This company is owned by two brothers who have vested interests, has no real concern on poor people.

Even after receiving donor fund, they claim to receive commissions from HGIL insurance company, the Beema Samithi is not aware of such company's existence who claim to do insurance business. This company has never registered them with any governing authorities. They received donor funds years ago claiming to do Micro-insurance business has done nothing so far but aiming to demand more donor funds trying to show false claim.

- Does this company have any prior experience in proven case of Micro insurance program conducted by them? if so where is the proof?

- Does this company have any experience in Nepal? if so they should submit their experience business report.

- Their business model is to collect commission on premium, if so are they been registered with Insurance regulator? How can a company claim to do insurance business without regulations?

- They received donor funds months ago, for any micro insurance business, they are to produce "social audit" indicating social impacts on poor (BPL) people. If they don't have any such proven impact results, these people are abusing the donor funds, plight of poor situation of any underdeveloped country.

Micro-justice a consortium club is raising the voice of the vulnerable poor demands accountable reports from all stakeholders using socially concerned media to bring out the issue calling for transparency in such operations.