Norway

Basic Data

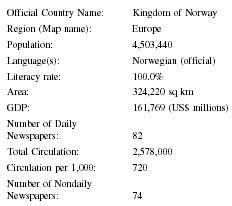

| Official Country Name: | Kingdom of Norway |

| Region (Map name): | Europe |

| Population: | 4,503,440 |

| Language(s): | Norwegian (official) |

| Literacy rate: | 100.0% |

| Area: | 324,220 sq km |

| GDP: | 161,769 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Daily Newspapers: | 82 |

| Total Circulation: | 2,578,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 720 |

| Number of Nondaily Newspapers: | 74 |

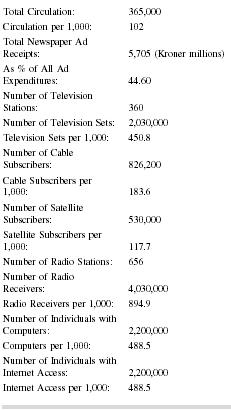

| Total Circulation: | 365,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 102 |

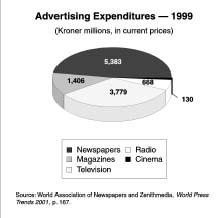

| Total Newspaper Ad Receipts: | 5,705 (Kroner millions) |

| As % of All Ad dExpenditures: | 44.60 |

| Number of Television Stations: | 360 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 2,030,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 450.8 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 826,200 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 183.6 |

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 530,000 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 117.7 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 656 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 4,030,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 894.9 |

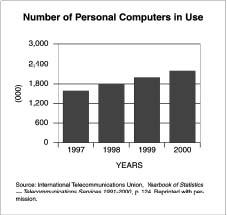

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 2,200,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 488.5 |

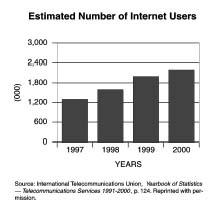

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 2,200,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 488.5 |

Background & General Characteristics

Norway is officially known as the Kingdom of Norway and includes a large mainland, a variety of small islands, and other territories totaling 385,155 square kilometers. Norway lies on the Scandinavian Peninsula and is surrounded by three seas to the west and shares most of its eastern border with Sweden. The northern section of Norway experiences cold winters and weeks of continuous darkness, along with weeks of continuous sun in the summer. The country includes large barren and mountainous regions and had a population of just 4.5 million people in 2001. In 1999 it was estimated that 28 percent of Norwegians live in one of the four largest urban areas, and only these four areas have more than 100,000 inhabitants. Oslo, the capital of Norway, has approximately 500,000 inhabitants; the next largest area, Bergen, has 220,000 inhabitants. Just 15 communities have more than 20,000 inhabitants.

Compared to most countries, Norway's population is overwhelmingly homogeneous. The vast majority of Norwegians are Nordic in heritage and appearance, and more than 60 percent have blue eyes. About 20 percent of Norwegians are under the age of 15, and 38 percent are married. Approximately 85 percent of Norwegians claim membership in the Lutheran Church of Norway, although most are merely nominal members of the state-run church with less than 3 percent attending regular religious services. Freedom to practice any religion is available to all. The language of Norway is German in origin, and modern Norwegian has several dialects but all are understood across Scandinavian countries. One written language, known as Riksmal, or "official language," was in place until about 1850. Landsmal, or "country language," was a written form created out of rural Norwegian dialects. A struggle over these two written forms resulted in both being given equal status. Over 80 percent of schools use Riksmal, now known as Dano-Norwegian (Nynorsk). English is a compulsory subject in school.

Norway was an agricultural society just 100 years ago. In 2000, the three largest sectors of employment were public services (40 percent), commerce, hotels, and restaurants (18 percent), and industry (17 percent). Norway is one of the world leaders in the exportation of petroleum. With an abundance of offshore oil and peaceful political and labor relations, Norway's standard of living is one of the highest in the world. Norwegians also rank among the highest in the world in projected life expectancy. A social democracy, Norway has a parliamentary monarchy with numerous political parties. A strong sense of equality dominates social policy. National health and welfare systems provide for all Norwegians, and include free medical care and full support in retirement or because of disability. Norway offers fully funded education for all Norwegians from 6 years old through a college education, and children are required to attend school for 10 years from the age of 6 until the age of 16. The government attempts to provide a high quality education to all citizens, regardless of geographical location, ethnicity, gender, social class or any other consideration, and is especially concerned that the educational system prepares citizens to compete in a world market. In 2000, among all Norwegians between the ages of 25 and 34 years old, 93 percent had completed at least an upper secondary education. Adult literacy in Norway exceeds 99 percent.

The development of Norway's press began with independence from Denmark in 1814. In the 1300s, clergy distributed handwritten reports of events. Printed reports seem to have begun in the 1600s. Norway's first full newspaper, Norske Intelligenz Seddeler, was established in Bergen in 1763. Censorship by the ruling Danish monarchy limited the content of early newspapers in Norway. By the end of the eighteenth century though, a few newspapers began to criticize the Danish monarchy and were influential in pushing Norway to declare independence. Denmark had ruled Norway for the previous 400 years, but turned over control to Sweden when Napoleon was defeated. To counter this transfer of control, Norwegians quickly created a constitution that called for the most democratic political structure to date, including a parliamentary system, the abolition of any further hereditary titles, and expanded voting privileges. Although a small elite still ruled Norway, this constitution resulted in the limitation of Sweden's control and has been maintained, with the addition of amendments, to this day. With independence and a democratically based constitution, modern Norway was designed to be open, a society in which all children have the right to be literate, and all citizens participate in decision making. A free press was thought to be essential for this and to make an informed nation out of such a dispersed population. To this end, the constitution provided for a free press, similar to the one developed earlier in the constitution of the United States.

The result was that Norwegian newspapers became important sources of information and commentary about the state of affairs in Norway. With industrialization in the middle of the nineteenth century, the press grew and began to participate in the political debates between liberals and conservatives. In fact, newspapers took sides and became associated with specific political parties. This partisan journalism survived through the 1990s. From 1900 until the start of World War II, some 80 newspapers opened their doors. However, many papers were subsequently eliminated with the Nazi occupation of Norway during the war, and many newspaper editors were imprisoned or murdered. Nonetheless, underground newspapers flourished as Norwegians risked their lives to keep their fellow citizens informed about the war and other international events. This news was obtained from short-wave radio broadcasts by the British. When the occupation ended, Norwegians were adamant about re-establishing a fully active and free press.

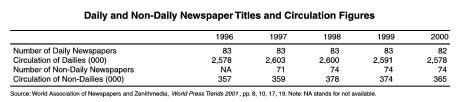

In 1999, Norway had 233 newspapers serving 117 different communities. For a country of just 4.5 million people, this is a large number of newspapers, although most are small and distributed less than three times a week. The 78 daily newspapers serve 62 different communities across Norway. Oslo, the capital of Norway, with a population of half a million, has nine daily papers and accounts for 42 percent of all newspaper production in the country. Norway has consistently led the world in per capita newspaper reading with an average household reading 1.65 newspapers a day in 1999. Unlike other countries that have experienced a substantial decrease in circulation at the end of the twentieth century, newspaper circulation remained consistent in Norway across the 1980s and 1990s. In fact, the only documented change in

The large number of small newspapers in this country is attributed to geography and government support. The numerous mountain ranges and fjords mean that the country has many isolated communities that require a unique paper to report on local events. In fact, the local press experienced growth in the 1990s whereas newspapers covering larger areas decreased circulation in that decade. However, in medium-sized cities where a major competitor exists for advertising, smaller, local papers have been challenged. The result is that generally only the larger paper survives, as only 10 communities have two or more local papers competing with one another. The large number of papers in existence is also possible because of economic support from the government. Tax breaks for all papers as well as subsidies for local papers that have small circulation numbers or other competing papers allow many newspapers to survive. This strong support for local presses may also reflect Norwegians distrust of centralized authority.

The largest Oslo newspapers include Aftenposten, Dagbladet, and Verdens Gang. Although these newspapers are available to the entire nation, local community papers dominate their individual markets. Bergen has the Bergens Tidende; Trondheim has the Adresseavisen, and Stavanger has the Stavanger Aftenblad. Popular business papers include Dagens Naeringsliv and Finansavisen. Although large headlines with popular appeal and photographs are prominent in Norwegian papers, the quality and extensiveness of the news reporting is considered high. In fact, the Aftenposten is recognized internationally as one of the elite daily newspapers in the world.

Economic Framework

Welfare capitalism flourishes in Norway. The economy features both free market activity and government control of key sectors, such as the management of Norway's rich natural resources and, in particular, the critical petroleum industry. Norway's economy is quite dependent on exporting oil. In fact, this small country is second only to Saudi Arabia in the amount of oil exported. Privatization of this industry began in 2000. Although Norway's economy is fairly robust at the beginning of the twenty-first century, concern over the expected depletion of petroleum resources in the next couple of decades is mounting. To prepare for this economic adversity, the government has invested internationally and, as of 2000, had investments totaling more than U.S. $43 billion. In 2000 the labor force consisted of 2.4 million workers with unemployment estimated at 3 percent. Despite an economic downturn in the late 1990s, Norway remained one of the top countries in the world in standard of living.

One substantial source of money for newspapers in Norway has been political parties. The party press developed with the political struggle over creating a parliamentary government in the 1800s. The press was the primary means for political debate and influence among citizens as nationally organized parties did not exist at the time. As parties developed, they subsidized newspapers in exchange for representing their political positions. Opposing parties would then subsidize other papers to present competing positions to the public. The economic role of political parties in the subsidy of newspapers flourished following the Nazi occupation. Because many papers were closed down by the German invasion, start-up money was needed to begin papers again. Political parties, in addition to trade unions, stepped in with substantial financial contributions. The 1950s and 1960s brought a downturn in the number of newspapers in Norway. Although advertising income increased during this time, it was unevenly distributed across papers. Large circulation papers received a disproportionate amount of the advertising money available as advertisers believed that the other competing papers in an area did not represent many additional readers. The economics of the newspaper business then led to a decline in political party involvement in the press as party papers typically had smaller circulations and could not survive.

The Norwegian government was then asked to subsidize smaller political presses to keep a diversity of political views available to the public. The cost of supporting all party-related presses in such a large multi-party political system was too high. As a consequence, the government chose to economically support only struggling papers, in particular, those with small circulations or stiff competition from other papers. These are intended to be objective criteria so that the government is contributing to a rich and diverse press, as opposed to advocating a particular political position. Quality of the paper is not a factor in these subsidies, and the government asks for nothing in return for the contribution. The goal is simply to maintain a well-informed and political savvy citizenship. These subsidies were authorized in 1969, and in 2000, the government spent 164 million Norwegian krone, the equivalent of 20.5 million Euro, on newspaper support. This support allowed the party presses to survive much longer than they would have been able to otherwise. Nonetheless, party presses became less economically viable as other methods for transmitting news became popular. With the advent of the state broadcasting system and its public service philosophy of including a wide range of political party views in its programming, party papers became obsolete. Those papers then had a journalistic dilemma of whether to continue to cater to those committed to a single political perspective or to become more comprehensive in the positions presented and risk losing their devoted base of readers. As a result news journalism began to develop in Norway at the beginning of the twentieth century; however, it has been slow to progress, not replacing political-party journalism until the start of the twenty-first century.

Advertising revenues declined substantially for both newspapers and broadcast media in 2001 and at the start of 2002. Moreover, the size of the subsidies provided by the government to enhance diversity in daily presses has declined substantially since 1990. As a result, some media enterprises have gone out of business or merged. In one medium-sized city, Bodo, two large daily newspapers decided to merge because of the loss of advertising revenue. These economic problems have led to concerns about competition, as large conglomerates are created. Although severely criticized for being ineffective, the Norwegian Media Ownership Authority (NMOA) was established in 1999 to prevent concentrations in ownership of the media. This was deemed especially important in light of the fact that only three groups own most of the daily presses and also have substantial interests in broadcast media.

Press Laws

The establishment of a free press in Norway was written into the Norwegian Constitution when it was created

In 1994, the Norwegian Press Association adopted an Ethical Code of Practice, covering the obligation of the press to protect freedoms of speech and information distribution and the obligation to offer critical commentary and a diversity of views. Although this is not a legally binding obligation, it serves as an important guideline for behavior for the press and is followed with much diligence. The code also addresses integrity and responsibility. For example, offering any sort of favors to advertisers is prohibited, and presenting accurate and truthful information is expected. Relationships with sources of information are also delineated. According to this national association, the press is obligated to use credible sources and to identify them when there is no need to protect them.

Press laws have not kept pace with changes in the media. For example, senior editors are held legally accountable for newspaper and broadcast media content, but it is unclear who should be held liable for published materials on the Internet. In 2001, a governmental committee was created to determine this. In support of freedom of the press, the national press associations in Norway oppose holding Internet Service Providers (ISPs) responsible for not removing material immediately that some authority deems unlawful, except in the case where a court has made a determination. In an effort to police themselves, a "liability label" has been created by the national association of editors for Webs sites that adhere to association policies. These policies include having an independent editor and agreeing to the other ethical and legal requirements delineated by the association. Many Web sites display this well-recognized label.

Censorship

Norway prides itself on its free press and does not condone censorship. However, during the Nazi occupation of Norway in World War II, censorship was prevalent. Journalists and editors were murdered, and many newspapers were shut down. The Germans tightly controlled the content of the remaining newspapers. As previously mentioned, Norwegians developed an underground press to combat this kind of censorship, as having informed and politically active citizens is an important value in Norway.

Norway offers free access to foreign media and is actively supportive of free press systems around the world. In 1995, 15 major media organizations developed the Norwegian Forum for Freedom of Expression (NFFE) to support and observe Article 19 of the United Nations (UN) Declaration of Human Rights that includes freedom of expression as a human right. The NFFE worked internationally and within Norway to protect and provide for freedom of expression. The NFFE lobbied against media restrictions in Asia, Africa, and Eastern Europe and participated in a variety of UN-organized conferences around the world. Within Norway, the NFFE monitored governmental policies that impact freedom of expression, organized conferences and seminars on the subject, and created cities of asylum in Norway for persecuted writers from around the world. The NFFE disbanded in early 2002. Norway, however, remains one of the most open countries in the world with regard to press freedoms. Even the government looks for ways to expand, not limit, access to information and freedom of expression laws. In 1999, for the first time since the creation of the Norwegian constitution in 1814, a special Constitutional Commission examined and made recommendations for revisions in Norway's freedom of expression principles. The revisions are intended to empower individuals and the media in terms of freedom of expression. The proposed revision in Article 100 of the constitution provides for the "right of access to the documents of the State and of the municipal administration, and a right to be present at the sittings of the courts and of administrative bodies." In addition, the state is responsible for creating "conditions enabling an open and enlightened public debate."

State-Press Relations

Among all professions, journalists stand out in their representation in the national assembly or Storting. Journalists seem especially eager to seek out the prestige of political party positions. For example, Nils Honsvald served as editor of the Labour party newspaper in Sarps-borg, the Sarpsborg Arbeiderblad, at the same time that he held a variety of political positions, including Storting representative, government minister, group leader for the Labour Party, and president of the Lagting and the Odel-sting, the small and large divisions of the Storting. Helge Seip was also a Storting representative and government minister while he served as the editor of Dagbladet, the third largest newspaper in all of Norway. Many others have served in politics while simultaneously working as editors of powerful newspapers as well.

However, since the 1970s the press has become more adversarial with the government. The Freedom of Information Act allowed access to all kinds of governmental activity. In combination with the development of news-journalism and investigative reporting, the press has become less respectful and more questioning of governmental officials. Despite the shift in relations, the government continues to acknowledge the necessity of a free press for an effective democracy and is supportive of this enhanced access to affairs of the state.

The press and the Norwegian government have been involved in collusion about what information should be made available to the public, especially during the Cold War. Journalists and politicians met and decided what information to pass on to the public and what to leave out. This kind of cooperation to suppress information was possible because of the close relationship between journalists and politicians. More specifically, newspaper editors and journalists held many of the key political positions in the country. When revealed, this practice was severely criticized. Many felt that the press had ignored its responsibility to be a watchdog for the public and to protect its own constitutionally guaranteed press-related freedoms.

In 2002, with the development of the profession of journalism, politically oriented papers have been replaced with politically neutral papers in which the goal is to represent as many positions on an issue as reasonably possible. This independent version of Norway's press is expected to be less likely to respond to any kind of censorship effort. In fact, by providing a variety of political perspectives on issues, politicians now need to be available to the press to provide them with any information necessary to explain their proposals and policies. Moreover, the press is thought to be responsible at least in part for the demise of political party loyalty. Half of all voters switch party allegiance from election to election, and minority parties are firmly established in the government because they have a voice for their views in this newly established independent press, despite limited membership or funds. The press then actually seems to have more political power and control about what is reported now then during the era of the political party press.

Broadcast Media

Over 650 FM, 5 AM, and 1 short wave radio stations were operating in Norway in 1998. Norwegians own over 4 million radios. Radio was especially popular in the 1950s and 1960s during which time Norwegians would gather to listen to radio theatre. During the Nazi occupation, radio was essential because it was a primary source of information, as Norwegians could receive broadcasts from the British Isles. Although the Nazis banned radios, many families turned in one radio to the Germans but had another hidden in their homes. Radio is not as popular at the start of the twenty-first century because of the prevalence of televisions and Internet connections. Many Norwegians continue to use radio for short periods of time to get updates on news and weather. More than 60 percent of Norwegians used a radio on a daily basis in 1997, yet that represented a decrease of 10 percent since 1991.

The state broadcast system was a monopoly until 1981. Two television channels serve all of Norway. The first, the Norwegian broadcasting channel (NRK), has existed the 1960s. Not commercially funded, the channel requires a fee from all who have a television in Norway. The amount of time spent watching this station is irrelevant as all pay the same fee. The second nationwide channel, TV2, began broadcasting in the 1990s and is supported by commercials. Although NRK has been in existence much longer, both channels have about the same number of viewers. Other channels are available to Norwegians through the use of cable or satellite dish connections. These channels include local stations, other nationwide stations, and foreign stations. The Act on Local Broadcasting that passed in 1988 allowed for permanent local broadcasts. Oslo has some 72 different television stations available to viewers. It is notable that Norwegian laws prevent television stations from interrupting shows with commercials, and commercials are limited in their length. Even the shortest of infomercials have been sanctioned. Norwegians have approximately 2 million televisions for a population of 4.5 million.

In 1996, TV2 filed a lawsuit against the government arguing that the state had breached its agreement with the

Electronic News Media

All forms of news are duplicated to some degree on the Internet in Norway. Leading Norwegian newspapers, such as Aftenposten,Dagbladet,VG, Morgenbladet, and Nytt Fra Norge have Internet versions of their papers.

The Aftenposten Web site offers a more compact version of its printed daily edition and allows the user to go directly to an overview of the news or to an outline of the paper's contents. Several regional and local newspapers also have Web sites of their contents. Regional newspapers

Thirteen Internet Service Providers are available, and 2.36 million people were Internet users in Norway in 2000. Norway ranks fourth in the number of Internet connections per capita. The internet code for Norway is.no.

Education & Training

The number of journalists in Norway increased dramatically as advertising income blossomed. Even though the number of newspapers declined substantially beginning in the 1950s, the size of newspapers grew tremendously, as did the number of journalists. The Norwegian Union of Journalists saw its membership double between 1960 and 1975, and then again by 1987 to 4,494 members. This increase sparked meaningful union activity that resulted in increased wages and improved working conditions for journalists. The union also sought input from their members when editors were appointed or promoted. As owners suspected, this was a move to limit owners' and editors' ability to present their own particular slant or political position. In addition, with the transition from a party press to a news journalism approach, the press became more professional and independent. The job market was then open to all based on ability as opposed to party affiliation, and staunch party journalists were able to seek positions with papers that were in direct opposition to their political persuasion. Journalistic methods of analysis and investigation were the qualities now sought in journalists.

Education and training of journalists in Norway is varied. Universities in Norway offer journalism and mass communication programs, and internships and apprenticeships allow for on-the-job training. Although anyone can work as a journalist and use the title of journalist, a university education is expected for most professional positions. Higher education programs in journalism are professionally oriented and qualify graduates to work in print or broadcast media. The Volda University is the central institution in Norway for a broadcast journalism education. This small college includes a Faculty of Media and Journalism, which offers bachelor's programs in journalism, media, and information and communication technology and design. Oslo University College has a Faculty of Journalism, Library and Information Science offering a variety of programs. Two-year programs in journalism and photojournalism are offered. The journalism programs address how to find, evaluate, critique, and convey information. A master's degree in journalism became available in 2001 in cooperation with the University of Oslo. This degree addresses subjects such as the history of journalism, cross-cultural communication in Norway and abroad, professional journalistic identity, and research in journalism. The University of Oslo offers degrees in journalism through their Journalism and Media and Communication Departments. These professional programs focus on the means and methods of journalists and include scientific and critical analysis of the field of journalism.

Summary

Norway enjoys a free press and a large number and rich variety of newspapers covering even some of the smallest and most remote communities. Norway's press grew from handwritten sheets produced by clergy in the 1400s to a long run for a multitude of newspapers through the start of the twenty-first century. After a press dominated by political party influence with newspapers representing particular political positions, Norway press has come to value independence and the presentation of a range of perspectives on issues. Censorship is virtually nonexistent in Norway, and few laws restrict the press in any manner. Journalism is considered an honorable and important profession. In 2002, broadcast media dominated in Norway, and Norwegians were fully in tune with the most modern means of communication, including an abundance of Internet connections, access to satellite transmissions, and a large percentage of cell phone users.

Significant Dates

- 1814: The Norwegian Constitution is created and establishes a free press.

- 1969: The government authorizes subsidies to ensure a diversified press, providing for local and small circulation newspapers.

- 1981: The state broadcast system is no longer a monopoly.

- 1988: The Act on Local Broadcasting is passed allowing permanent local television broadcasts.

- 1994: The Norwegian Press Association is adopted an Ethical Code of Practice.

- 1995: Fifteen major media organizations develop the Norwegian Forum for Freedom of Expression to support Article19 of the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights representing freedom of expression as a human right.

- 1999: A special Constitutional Commission recommends revisions in article 100 of the Norwegian Constitution to allow for more extensive freedom of expression protections; the Norwegian Media Ownership Authority is established to prevent concentrations in ownership of the media.

- 2001: A governmental committee is established to decide on legal liability for publication of materials on the Internet.

Bibliography

Hoyer, Svennik. The Norwegian Press. Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Available from http://www.odin.dep.no .

"Norway." Culture Link. Available from http://www.culturelink.org .

"Norway." World Press Freedom Review. Available from http://www.freemedia.at .

"Norwegian Media Links." Media Links. Available from http://www.cyberclip.com .

Melanie Moore

One should be equal as long as Human Being.

Underprivileged social class,

Before the birth, even after the death,

this underprivileged group should follow the pre-framed given route.

Upon realizing that crossing the given route is limited,

its trial object would be named as ‘Betrayer’ or targeted as ‘Gov. Sanction’.

Extending of this status,

urged and resulted let David create hand written images between # 1 and # 58.

Still, there, no one, no response, no way to get out, its condition is extended.

Its uselessness, barren condition has been extended as usual.

David D Y Choi, March 2021

( e-mail ; dulywork@mailfence.com or cdyera@yandex.com )

cdyera wordpress com