Portugal

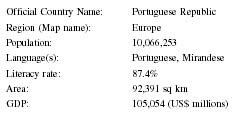

Basic Data

| Official Country Name: | Portuguese Republic |

| Region (Map name): | Europe |

| Population: | 10,066,253 |

| Language(s): | Portuguese, Mirandese |

| Literacy rate: | 87.4% |

| Area: | 92,391 sq km |

| GDP: | 105,054 (US$ millions) |

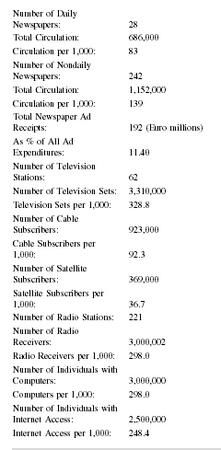

| Number of Daily Newspapers: | 28 |

| Total Circulation: | 686,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 83 |

| Number of Nondaily Newspapers: | 242 |

| Total Circulation: | 1,152,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 139 |

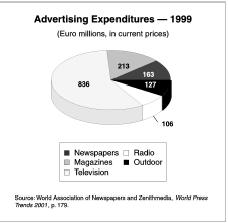

| Total Newspaper Ad Receipts: | 192 (Euro millions) |

| As % of All Ad Expenditures: | 11.40 |

| Number of Television Stations: | 62 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 3,310,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 328.8 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 923,000 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 92.3 |

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 369,000 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 36.7 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 221 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 3,000,002 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 298.0 |

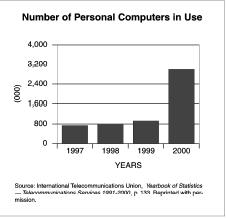

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 3,000,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 298.0 |

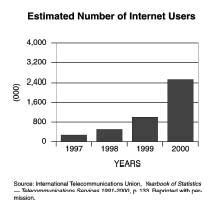

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 2,500,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 248.4 |

Background & General Characteristics

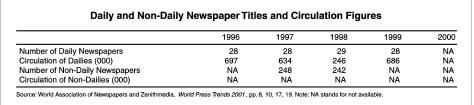

Despite a slow and steady movement away from government-controlled media and toward privatization throughout Portugal's business sector, the Portuguese press fights for life on a different battlefield. Print media struggles to gain a market-share in a country where the illiteracy rate is approximately 15 percent. As a result, most people in Portugal get their news from television or radio stations.

Daily newspaper circulation is among the lowest in western Europe, at 75 per 1,000 citizens. Among the factors driving this trend is the strict authoritarian control over the media during a long history of stifling political regimes. The result has been a mundane conformity in the media that led citizens to get their news elsewhere. Beginning with the 1926 nationalist military coup, Portuguese citizens lived under repressive fascist regimes for more than five decades. Even the National Library in Lisboa was affected, as secret police officials reviewed lists of books requested by readers. Foreign magazines were closely examined before being placed on newsstands, with entire stories being blocked out.

Later regimes relaxed the rules somewhat, allowing the press to publish thinly disguised "analysis" of elections in other countries, when everyone knew the topic was really the lack of free elections in Portugal. The weekly newspaper Expresso, which is still in print and considered a strong defender of press freedoms, tested the waters virtually every issue, floating stories certain to test the government's tolerance levels. Still, Portugal's mass communications industry did not undergo significant change until a radical but bloodless coup in 1974.

One of the new government's first acts was to abolish censorship. Portugal's current constitution guarantees free speech and absolute freedom of the press. However, a shift to the left soon came, resulting in the closing of the Socialist Party's Republica newspaper and the Catholic Church's Radio Ranascenca. Because most banks owned at least one newspaper, government control of the banking industry resulted in the state's ownership of many media outlets. However, by the beginning of the 1990s, all newspapers were owned by privately held companies.

The state did maintain operation of radio and television broadcasting systems, and in the mid-1970s, all stations—except those owned by the Catholic Church— were nationalized. Radio service was provided through Radiodifusao Portugesa (RDP). Only two television channels were maintained by the state-owned Radio-televisao Portugesa (RTP). Privatization began in the early 1990s; however, in July of 2002, Portuguese President Jorge Sampaio approved a law to give government greater control over state-run television, making it easier to close one of the two public stations. His decision was quite controversial. Sampaio, a Social Democrat, said the move was being made to restructure government television and keep the cap on Portugal's budget deficit, which cannot exceed three percent of gross domestic product. Sampaio's party claims the RTP has a multi-million dollar debt, which they blame on the Socialist-appointed board that controls the entity. The change in law would give government the power to appoint an RTP board. It includes more guarantees of impartiality than an earlier version, although critics charge this move will critically impact the RTP's ability to remain independent.

For their part, Portuguese journalists adhere to a Deontological Code adopted by the Syndicate of Journalists in May, 1993. Translated from the original French, the Code sets forth 10 basic principles that outline a journal-ist's duty, from reporting the facts accurately and in an exact manner to an admonition regarding discrimination based on color, race, nationality or sex. Journalists who adhere to the Code agree to fight restrictions in access to information and sources and attempts to limit press freedoms. Also included are conditions regarding the truthfulness and accuracy of information, keeping good faith with sources and respecting citizens' private lives.

As of 1999, only one newspaper, O Correrio da Manha , a Lisboa-based daily considered somewhat sensationalistic, was owned completely by journalists. Director Victor Direito, considered one of the profession's greatest, serves as director and co-owns the paper with manager Carlos Barbosa. Direito takes regular political shots in a daily column. O Correrio da Manha has the largest circulation in the southern part of the country.

Portugal has 28 daily newspapers, the largest of which is the popular Jornal de Noticias , which has a circulation of more than 109,000. The Jornal is in a class by itself; its main rivals fall into the 50,000 to 70,000 circulation category. Others may enjoy a larger circulation, but the Diario do Noticias is considered the country's most prestigious publication, as it is an official newspaper of record. Most major newspapers are dailies and cover a wide variety of interests, from national and local news to business and sports. Founded in 1990, Publico is an independent news source contains sections dealing with both Lisboa and Porto, making it one of the best sources for national news. Of three afternoon newspapers that were printed in the 1990s, only one— A Capital —has survived, but just barely with a circulation of only about 10,000.

Additionally, two news magazines— Expresso and O Independente —serve as the country's counterparts to Time and Newsweek , published in the United States. Expresso enjoys the largest circulation overall, more than 136,000.

Publications with the largest circulation are largely magazines that represent feminine, popular and entertainment interests. By Maria tops the list with more than 314,000 copies in print, but a number of Portuguese magazines have circulations well over 100,000.

Portugal's largest circulation newspapers maintain web sites, and a handful of Internet news outlets have been created over the past several years, including a service that specializes in the Azores. Various local newspapers serve all provinces; not surprisingly, the largest number can be found in Lisboa, Portugal's capital. All of the major daily newspapers are based in Lisboa, which is served by a total of 15 newspapers. The Azores, located along the western shores of Portugal, has 10 newspapers and one internet-based publication, the Azores News . The province of Portos has the third highest number, eight. Most areas of the country, from the rough terrain in the north to the sweeping plains in the south, are served by at least one newspaper.

The majority of newspapers are published in Portuguese, the country's official language, and have a regional distribution. A minority of the population speaks Mirandese, a Romance language that began to emerge about the middle of the twelfth century. Considered a dialect of Portuguese, the language is spoken primarily in the mountainous northern area of the country amongst a population of fewer than 15,000. It is used in some regional newspapers that serve those areas and special projects have been launched by the government to promote and spread its use in the media and other areas of Portuguese culture.

Counting national and regional newspapers, news and specialty magazines, more than 1,300 publications are distributed in Portugal. Every year 552,682,095 copies of those are printed. All in all, Portugal is home to enough newspaper, radio and television outlets to create a number of venues for public discussion of issues and a healthy political dialogue in a country whose 10 million citizens are represented by five political parties— Populist, Communist, Socialist, Democratic and the Left Bloc. However, sports newspapers, with a circulation of up to 100,000 copies per day, lead the market. Portugal's three sports newspapers have combined sales of 230,000.

Economic Framework

With nearly 40 percent of its land forested, it is no wonder paper products are readily available in Portugal. Wood pulp, paper and cork are among the country's leading industries, along with textiles and footwear, metal working, oil refining, chemicals, fish canning and wine. Portugal also hosts a healthy influx of tourists through its booming hospitality industry. The country exports $25 billion in clothing and footwear, machinery, chemicals, cork and paper products and animal hides annually.

Portugal's economy grew steadily between 1986 and 2000, about 3.6 percent per year after a rapid expansion in the first few years after joining the European Union as its poorest member. The investment boom driving that expansion slowed in 1999 and continued slower growth is projected in the coming years. However, key investment projects are expected to improve Portugal's transportation system, including construction of a new airport in Lisboa.

Newspapers have a significant effect on Portugal's economy. Nearly 4,000 companies are involved in the paper/printing/publishing industry, employing 50,000 Portuguese citizens. Despite a relative economic boom and increased wages in other industries, Portuguese journalists are among the most poorly paid in Europe, which tends to weaken independent journalism. Journalism schools in Portugal are said to produce as much as four times the number of reporters needed throughout the country.

In 1999, the country's major investors took an interest in the media. At the end of that year, businessman and speculator Joe Berardo sold a press group and his stake in television station SIC, owned by former Prime Minister Francisco Balsemao. Corfina, the owner of a sports newspaper and a couple of women's magazines, picked up his SIC shares. Portugal's two television stations run at a huge loss, and Portuguese President Jorge Sampaio cited a $991 million deficit in July of 2002 as the basis for his approval of a law that would give the government more control over appointments to a board that oversees the State's two television stations. The privately owned SIC has maintained a healthy financial position, posting profits of as much as $38 million in 1998.

As government control has eased, Portugal grows increasingly toward a capitalistic economy, which is dominated by the service industry that comprises 60 percent of the country's gross domestic product. While Portugal has experienced eight years of economic growth that surpassed the European Community average, investment

Press Laws

After decades under government control, Portugal now has a constitutionally free press. Portugal's constitution has been amended to include provisions for access to public documents as well as safeguards for a free press, and a body of legislation called The Press Law deals not only with the rights and duties of journalists but also the organization of the companies that employ them. In Portugal, freedom of the press includes the freedom of expression and creativity for journalists, as well as a role for the journalists in giving editorial direction to the mass media. However, the Constitution makes an exception in the latter area with regard to publications owned by the State or which have a "doctrinal or denominational" character.

Journalists, along with all Portuguese citizens, are guaranteed the right to access sources of information and government documents. The right to professional independence and secrecy are also constitutionally ensured. The state has provided for freedom of the mass media against both political and economic powers, preventing economic monopolies from controlling a free press.

Article 37 of Portugal's constitution ensures the right to free expression and the right to inform and obtain information

As constitutionally defined, freedom of the press includes freedom of expression and creativeness for journalists, the journalist's right to access information and protection of their professional independence and secrecy; the right to start newspapers and any other publication without government interference.

The structure and operation of the media are to remain in the public sector to ensure independence against public bodies. Additionally, the constitution provides for a High Authority for mass media that secures the right to information, the freedom of the press and an independent media. The High Authority is made up of 13 members, five of whom are elected by the country's lawmakers, three appointed by government and four representing "public opinion, mass media and culture."

Censorship

Censorship was abolished following a government coup in 1974. Portuguese media are protected by the constitution from interference byeither government or business. The Portuguese media is governed by a High Authority designed to ensure press freedoms and access to information are maintained. The 13-member board includes five members appointed by the legislative Assembly, three appointed by the state and four who represent media and the public. While there is no overt censorship of the press, there have been several related controversies over the past few years.

Most recently, in 2001, a furor arose when the Portuguese version of the reality show "Big Brother" was cited for obscenity by the High Authority, after showing two of the contestants having sex. The broadcaster, TV1, was heavily criticized by both government and religious leaders; Bishop Januario Torgal Ferreira said, "I am shocked. People are selling their souls." After another channel, SIC, was also criticized for invading people's privacy with the show "O Bar da TV," Portugal's media took matters into their own hands, forming a self-governing board to monitor the contents of their programming. The board is completely separate from the High Authority.

Libel prosecution, which can be a form of censorship, became a cause for concern in 1997. Two journalists were convicted of libel for an article they had written on drug trafficking, and a libel suit was launched against television station SIC based on broadcast reports that Portuguese soccer players had smoked hashish prior to an international match in 1995. Also that year, a series of exposes about the media's rich and famous published in the weekly Seminario resulted in bomb threats called to the editor, Alvaro de Mendonca, at his Lisboa apartment. While the series' author was not identified and wrote under a pseudonym, he was suspended by the company's management, leading critics to claim self-censorship.

State-Press Relations

While relationships between Portugal's government and press are nowhere near the level of control and suppression as under earlier fascist regimes, critics of the current government claim leaders are trying to exercise more control. Efforts by the Social Democrat party to gain more government control over a board that oversees the state-run television station RTP succeeded in July of 2002. Under the changes, the government has the power to unilaterally appoint a board to run the RTP. Sampaio claimed the move was necessary because the station was running at a multi-million dollar deficit, caused by the Socialist-appointed board.

In 1998 and 1999, Portugal was among only 11 countries where no press freedom violations were recorded.

News Agencies

Only one national news agency, LUSA, serves Portugal. Founded in 1987, the news agency provides home, national, foreign, economic and sports news, as well as home and foreign photos. LUSA employs nearly 300 staffers, the vast majority of whom are reporters. Portugal also has one domestic press agency, Agencia Ecclesia, which is smaller and serves domestic and local news outlets.

Broadcast Media

Eight national broadcast stations and one foreign station, CNN, serve Portugal. The industry was monopolized until the start of the 1990s by state television broadcasters RTP1 and RTP2. As a result of bringing the country into line with the Economic Union's views, the privately owned SIC, owned by a prominent Social Democrat, has become the most popular television station in the country. Among radio stations which serve Portugal: ESEC Radio, Radio Comercial, Radio Difusao-Antena 1, Radio Difusao-Antena 2 and TSF news radio.

Electronic News Media

Portugal's major newspapers have electronic versions, and several electronic newspapers are published on the World Wide Web: Euronoticias, Informação On Line, Jornal Digital and Lusomundo. includes a number of links to information about Portugal, particularly in the area of entertainment. Internet access has expanded to the point where 20 licensed operators provide Internet access. However, only about 10 percent of the population over age 15 had access to those services as of 1998. Increasing competition and an ever-expanding range of services has kept the demand for Internet very high.

Education & Training

Not surprisingly, the stifling dictatorship that governed the media during the Salazar regime (1926-1974) also ended the education of journalists. The government elite felt citizens should only be educated to follow government direction; thus, the education of journalists, who could use what they learned against those in power, was considered contrary to the government's best interests.

Nevertheless, the National Union of Journalists in 1940 developed and planned the first-ever education program for journalists. The two-year course, which could be attended by anyone with nine years of primary and secondary education, never got off the ground due to the absence of governmental support. Because journalism primarily involved the parroting of government press releases, even those in the profession did not consider education important.

It took another 30 years for education to become a priority, as the Journalists Union proposed a far more extensive course of study to which a student would commit 24 hours per week. In all, about 60 courses would be offered over a period of five years in the fields of Social Sciences and Journalism/Communications. According to union officials, this program suffered from an over-abundance of government intervention, with three separate agencies vying for control over the program. Additionally, a private journalism course was being developed

Five years after the revolution, the Universidade Nova de Lisboa set up the first university communications program of study, which was quickly duplicated by Universidade da Beira Interior and in the Universidade do Minho. These programs focused on the philosophical aspects of journalism and trained reporters in languages, so they would not be easily deceived or manipulated. Rather than stressing technical expertise, they took a broad-based approached to media and communications.

In the 1980s, more technical programs were developed, through Centro de Formação de Jornalistas (CFJ) and Centro Protocolar de Formação de Jornalistas (CENJOR), which gives special attention to local and regional media.

Currently, 27 programs of education are offered for journalists in Portugal; another 30 are media-related. Only one program is specifically titled Journalism. It has been offered at Universidade de Coimbra since 1993. About 1,500 students begin a course of media studies each year at public and private universities. Even though Portuguese journalists are among the lowest paid in Western Europe, competition for newsroom positions is fierce.

As Portugal's press grows and changes, so does the system for educating its journalists. Though many in the profession still do not have formal training, attitudes toward education are becoming more positive as the benefits of an informed and educated media are seen.

Summary

The Portuguese media is making a slow but steady recovery from decades of government-imposed oppression and mediocrity. Competition within the industry has led to improvements in journalistic standards and ethics, as well as an increasingly educated professional base. Although the government owns several media outlets, Portugal's diverse and active press corps keeps citizens informed and helps maintain an open dialogue about government and politics that was missing for nearly five decades. Some areas still bear watching, such as the government's move to exercise even greater political control over the state-run television stations. As Portugal's society becomes more accustomed to a wide variety of broadcast offerings, issues of censorship and self-policing media are being debated and addressed. It is worth noting that Portugal's government has taken a public stand against violence toward journalists and has encouraged other members of the Economic Union and United Nations to explore new ways inspired by technology to bring even more information into the world and bridge the gap between the "haves" and "have nots."

Significant Dates

- 1934: The National Journalists Union is established.

- 1937: Rádio Renascença (RR) starts broadcasting.

- 1940: The first training program for journalists is developed by the National Union of Journalists, even though it is never actually offered.

- 1974: A bloodless coup d'état leads to the establishment of a free press.

- 1979: The first university program specializing in journalism is established.

Bibliography

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). World Factbook 2001 . Directorate of Intelligence, 2002. Available from www.cia.gov .

Committee to Protect Journalists. Country and Regional Reports: Portugal . 2002. Available from www.cpj.org .

Country Files: Portugal . British Broadcasting Company, 2002. Available from news.bbc.co.uk .

European Media Landscape: Portugal . European Journalism Media Centre, 2001. Available from www.ejc.nl .

Obrigado! News and Media. 2002. Available from www.obrigado.com .

Pinto, Manuel, and Helena Sousa. "Universidade do Minho: Journalism education at Universities and Journalism Schools in Portugal." In Journalism Education in Europe and North America: an International Comparision , R. Frolich, ed. Victoria, Australia: Hampton Press, 2002.

"Statement to the Twenty-second Session of the UN Committee on Information." WEOG/UE joint-statement, with the agreement of Mr. Sebastião Coelho, representative of Portugal, on behalf of the European Union. Available from www.un.int/portugal .

University of Tampere, Finland. European Codes of Ethics: Portugal . Available from www.uta.fi .

U.S. Department of Commerce. National Trade Data Bank . November 3, 2000. Available from www.tradeport.org .

World Press Freedom Committee. 2002. Available from www.wpfc.org .

World Press Freedom Review: Portugal . Reviews for 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000 and 2001. Available from www.freemedia.at .

Joni Hubred

I would simply like to find out the name and address of the foreign newspaper/magazine distributors in Faro/Algarve during the mid 1970s.

Please email me with any information at kimmomania@gmail.com

Many thanks