Russian Federation

Basic Data

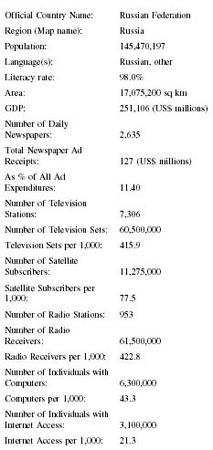

| Official Country Name: | Russian Federation |

| Region (Map name): | Russia |

| Population: | 145,470,197 |

| Language(s): | Russian, other |

| Literacy rate: | 98.0% |

| Area: | 17,075,200 sq km |

| GDP: | 251,106 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Daily Newspapers: | 2,635 |

| Total Newspaper Ad Receipts: | 127 (US$ millions) |

| As % of All Ad Expenditures: | 11.40 |

| Number of TelevisionStations: | 7,306 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 60,500,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 415.9 |

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 11,275,000 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 77.5 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 953 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 61,500,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 422.8 |

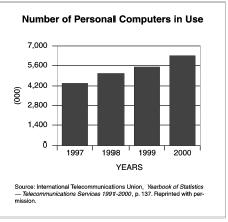

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 6,300,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 43.3 |

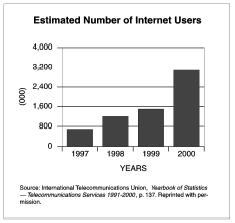

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 3,100,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 21.3 |

Background & Characteristics

On the eve of its breakup in December, l99l, the Soviet Union had a population of about 291 million, the third largest in the world. Great Russians made up a slight majority of 52 percent. Non-Russian Asians were clearly growing sharply in numbers and as a percentage of the total population. With the collapse of the USSR, the Russian Federation's population was down to l45 million. Great Russians totaled 82 percent of the entire population. Of much greater significance, the birthrate in Russia was 9 per l,000; the death rate was l4 per l,000.

In the early 2000s, Russia was a largely urbanized nation with about 66 percent of the population living in cities. The largest cities in Russia were Moscow with 9 million, St. Petersburg (formerly Leningrad, 5 million), Nizhni Novogorod (l.4 million), Novosibirsk (l.5 million), Yakaterinburg (l.3 million), Samara (1.2 million) and Omsk (1.1 million).

Russia has one of the greatest literary traditions in the world. From Pushkin and Gogol to Dostoyevksy and Tolstoi, down to Pasternak and Solyzenitsyn, the Russian people have always enjoyed great literature and poetry. By contrast, the press and modern journalism came relatively late to Russia. The first printing press reached Moscow only in l564. Peter I founded the first newspaper in Moscow, Vedomsti ( The Bulletin ) in l703, and technically it lasted until l9l7. At the beginning of the twenty-first century Russian journalists looked forward to celebrating the 300th anniversary of the founding of the paper in 2003.

But everyday realities in Russia worked against a mass circulation press. The vast majority of the Russian people were rural, poor, and illiterate. Enormous distances made travel difficult, and production, transportation, and newspaper distribution very expensive.

The reign of Alexander II (l855-8l) marked the real beginning of Russia's popular press age. The Great Emancipation of l86l ended serfdom across Russia, and Alexander's attempts to promote education vastly expanded literacy. Censorship laws were modified and revised, though censorship in Imperial Russia continued down to l906.

In Western Europe the free press co-occurred largely with democracy and the growth of capitalism and the market economy. In Russia, the popular press developed in a far more inhospitable environment. The press emerged either as an arm of the government relying heavily on state subsidies or among opposition thinkers, many of whom were in and out of prison. Russian (and later Soviet) intellectuals often saw themselves as almost a separate priesthood with a sacrosanct knowledge of "truth." In the nineteenth century many actually were sons of the Russian Orthodox priesthood, in which marriage was a requirement of ordination. They were known as the raznochintsky or classless intellectuals, and they formed the backbone of early dissident and later revolutionary movements. They were often highly intolerant of any but their own beliefs, a characteristic of many Russian intellectuals down to the early 2000s.

The first systematic publication of free, popular press occurred abroad, most of all in London and Paris, to avoid Russia's harsh censorship. I. G. Golovin put out The Catechism for the Russian People in Paris in l849; Alexander Herzen began publishing his works in London in l853. Then in l863 Andrei Kraveski began publication of the first independent Moscow daily, Golos ( The Voice ). Unlike previous Russian newspapers, it was not dependant on government subsidies and clearly maintained a liberal, reformist perspective. Many young Russian writers got their start writing for the new popular press, most famously Anton Chekhov. In l863 the government removed heavy restrictions on advertising in the press, thus allowing genuine press independence. Then in l880 Russian newspaper circulation actually exceeded that of magazines. Yet the census of l897 revealed that nearly four Russians out of five could not read or write.

In l908, St. Petersburg readers saw the launching of the Gazeta Kopeika ( The Kopeck Gazette ) which rose to a circulation of 250,000 in l909, nearly twice the circulation of the next leading paper, Russkoe Slova ( The Russian Word ). In the meantime, the Russian book publishing industry, both fiction and non-fiction, expanded tremendously. On the eve of World War I, Russia in publishing 30,079 titles was the second largest book publisher in the world, after Germany.

With the onset of World War I, almost all the Russian press rallied to the Czarist cause. Newspapers became vital in news-starved Russia. Russkoe Slova , conservative and semi-official, had a circulation of 325,000 in l9l3 that rose to over one million by l9l7. The free press helped enlighten the Russian masses in that fateful year and also played a vital role in undermining Kerensky's Provisional Government. It helped make way for a new world in November, l9l7.

Vladimir Ulyanov Lenin understood, as few men of his time, the force of ideas and the power of the press. Published in St. Petersburg in l905, the first legal Bolshevik ( Communist ) newspaper, Novya Zhizn ( New Life ) was partially initiated by Lenin. Pravda ( Truth ) was published in Moscow in l9l2 but suppressed in l9l4.

On November l0, l9l7 (three days after the Revolution), the new Bolshevik government issue the "Decree on the Press," and the "General Regulation of the Press," which essentially eliminated all opposition media (and re-established censorship in Russia, a far tighter and more thorough censorship than the media had ever known under the Czar). During the period 19l7-l8, the Bolshevik government closed down 3l9 bourgeois papers. In l922 Soviet authorities formally created the Glavnit (censorship office). In l925, the state information system of the USSR headed by the Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union (TASS) was established.

Still the Leninist period (l9l7-25) marked a relatively liberal period in the new Soviet age. In July, l922, at the height of the New Economic Policy, the ten-page edition of Izvestia ( The News , the official paper of the Soviet state), had over five pages of advertising. In l925, book production in Russia exceeded the l9l3 level, even though Soviet Russia had lost Finland, the Baltic States, and Poland along its western littoral. The Communist regime put tremendous emphasis on education and literacy in the countryside. By l939, the literacy rate was over 8l percent in the Soviet Union, over twice the rate it had been in l9l4. At the same time, there was an enormous increaseboth in the number and variety of publications, both in Russian and in a host of minority languages.

But the Russian people paid a heavy price for this new literacy. Russian literature, especially after l928, was dominated by Stalin's "socialist realism," which emphasized the positive achievements of a socialist society. Most newspaper reporting was dull, turgid, and pedantic. Soviet newspapers (led by Pravda and Izvestia ) were physically small (usually six to eight pages) and filled with official announcements and the full text speeches of party officials. There were few photos, and these were usually staged and carefully edited (often editing out political "non-persons"). But in a society starved for news and information, even these kinds of newspapers played a vital role. During the Great Patriotic War of l94l to l945, Soviet newspapers were critical in informing, propagandizing, and maintaining morale across the country, at the front, and even behind the front, among hundreds of thousands of partisans behind German lines.

After World War II, the Soviet peoples had to endure drastic economic shortages and privations, strict censorship, and a cult of the individual, which glorified Stalin. With his death in l953, Soviet media underwent some liberalization and some qualitative improvement, especially with the arrival of slick, Western style magazines. There was a noticeable improvement in the number and quality of newspapers. Headlines became larger, articles shorter, and photographs were more frequent. The number of newspapers per 100 Soviet citizens over the years grew: there were 2 copies in l9l3; 20 in l940; 32 in l960; and 66 in l980.

The most important newspapers at the height of the Soviet era included Pravda with a single issue circulation of l0.7 million (making it the largest circulation newspaper in the world); Izvetia 7 million, Komsomol's Kaia Pravda ( Komsomol Truth ) 10 million, Sel'skaia Zhizn ( Rural Life ) 9.5 million, Trud ( Labor ) 12.2 million, Sovietskii Sport ( Soviet Sports ) 4 million, Literaturnaya Gazeta ( Literary Newspaper ) 2.6 million, and Krasnaya Zvezda ( Red Star ) 2.4 million. All of these were heavily subsidized by the Communist Party or the Soviet state and were remarkably cheap and popular—or at least widely read, if not popular in the Western sense. All clearly had teleological and political messages. In l980, newspapers were published in 55 languages of the peoples of the Soviet Union and in ten foreign languages.

The collapse of the Soviet Union resulted from many factors including economic failures, inflexible leadership (until Gorbachev when it was too late), and ever-increasing amounts of knowledge which first seeped and then flooded in from the West. The quality of Soviet press and media greatly improved by the l980s and so had access and dissemination of information. But the Soviet people's hunger for knowledge and information had exploded exponentially. The Russian people lived more poorly than people in the West and increasingly, through foreign media and word of mouth, theyrealized it.

For a long time, dissidents and others blocked from official press sources had adopted a policy of samizdat (self-publication). Originally these private journals, newspapers, and newsletters were written longhand and circulated privately. Later these papers were often mimeographed. The most famous of all samizdat publications was The Chronicle of Current Events , which was founded in l968 and continued in form or another until l990. In the last years of the USSR, samizdat writings were often Xeroxed—frequently by Soviet or Communist Party officials using state or party facilities and offices at night or in off hours. In the l970s the basic print run of samzidat publications was from 20 to 50; in the early l990s, it was sometimes in the tens of thousands.

Exemplified by George Orwell's 1984 , in the l940s and l950s, mass media, technology, and control of information did not necessarily favor the totalitarian state. The August, l990, Law on the Press of the Gorbachev era laid the legal foundation for print media independent of state direction. New independent, privately owned publications and newspapers were allowed. Former official or party newspapers were often bought or brought together by founders or by independent entrepreneurs who determined the policy and content of the papers. Existing assets of media were often simply claimed by those in charge, without any formal kind of compensation or payment.

The revelation of the abuses of Stalinism and Communist duplicity and corruption drove newspaper circulation to exponential highs. Ogonyoky 's ( Flame or Beacon ) subscriptions went from 600, 000 to 3 million. Komsomalskaya Pravda nominally a weekly youth magazine, reached a circulation of 20 million. Argumenti I Fakti , another weekly, which a few years before went out to 10,000 party propagandists, now topped 35 million. For a few years it was the most widely circulated periodical in the world.

The collapse of the Soviet Union and the Communist Party on Christmas Day, l99l, opened a tremendous media void, creating enormous opportunities for new sources and entrepreneurs who quickly moved in to fill the vacuum. The result was media anarchy and a general information and entertainment free for all.

The Russian Federation that emerged from the old Soviet Union was physically smaller (about 76 percent of the former USSR, though, by far, the largest nation in the world). Almost all the territory that Russia lost in breakaway republics was overwhelmingly non-Russian. In the last days of the Soviet Union, the Great Russians were 52 percent of the population, Ukrainians were l5 percent, and Uzbeks and other Asians were also about l5 percent. Many Russians had commented on the gradual "yellowing" of the population. As of 2002, about 82 percent of Russia was Great Russian with Tatars making up 4 percent of the population.

As is common after the fall of dictatorial regimes, the free press moved in, enthusiastically but uncertain of its role. For a while, it saw itself as the key factor in liberating the nation and playing a central role in reforming Russia. The period from l988 to l992 marked what many feel was the "Golden Age" of the Russian press. The press saw itself as an equal partner with the new reformist government. As in the nineteenth century, intellectuals and journalists saw themselves as the "conscience of Russia." There was an explosion of new publications, representing every imaginable cause and issue, not all responsive or responsible. The new atmosphere allowed journalists to appropriate media outlets, especially those in large cities, and particularly those, which formerly belonged to the Communist Party.

One Western author, Scott Shane, cited just a few of the new newspapers in the wide spectrum and the causes which they purportedly championed at the time: Democratic Russia (pro-Yeltsin Reformist coalition), The Alternative (Russian Social Democratic Party), Prologue (Federation of Independent Trade Unions of Russia), Nevsky Courier (Leningrad People's Front), The Cry of Yaroslavl (a military reform group called Parents of Soldiers), Charity (Soviet Charity and Health Fund), Under One's Breath (Moscow Organization of the Democratic Union), Christian Politics (Russian Christian-Democratic Party), Lightning (Communist Initiative), Freedom (Moscow chapter of memorial; all profits go to survivors of the Gulag), and Crossing (veterans of the Afghan War).

There were in addition, scores of other, non-party independent political papers, religious newspapers, and papers that took up every conceivable cause and issue, for example, animal rights, the environment, and UFOS. There were also a number of intensely nationalist papers and several Jewish and anti-Semitic publications. Many newspapers lasted but a few issues. Most, in keeping with the Communist tradition, were but a few pages long. Some were polemics. Others were tabloids.

The new Russian press thrived on scandals and exposes. The Boris Yeltsin regime provided plenty of material. Many papers and journals accused the government of negligence and corruption, as well as bribetaking and cover-ups. A score of Russian journalists and newsmen were killed in their efforts to expose corruption and government connections to organized crime. Other newspapers and forms of media were themselves accused of being in on the corruption and cover-ups. Papers and other media seemed to be "journalists for hire." They cranked out favorable publicity for those who paid them or character assassination or the threat of character defamation for those who did not. Some deputies in the Duma actually paid to be shown on television. Paid-for articles, nicknamed dzhinsa , became widespread in both new and traditional Russian media and did much to discredit the veracity of Russian journalism.

The "golden age" of the Russia press was predictably short-lived. Economic conditions took a sharp down turn in the early l990s, especially as artificially low prices, were allowed to float in l992 in the privatization of Russia's economy, and most promptly moved sky-ward.

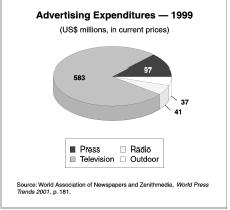

The Russian print media were caught in a classic economic ldbquo;scissors" crisis. On the one hand, with the removal of price controls, costs for all raw materials rose exponentially. From l990 to l99l, the price of news-print alone increased five to seven times. The same happened to the costs of ink, transportation, and new equipment. Mailing costs tripled, but service noticeably declined. On the other hand, the heavy government subsidies that publications depended upon in the Soviet era practically disappeared. The new regime was unwilling and often unable to replace them. At the same time, advertising in the new Russian economy was far too weak and far too limited to take up the difference. What money was spent on advertising tended to go into the radio and television markets. Wages were appallingly low to begin with and were often paid months behind time or not paid at all. After accounting for inflation, some newspapers were paying their employees ten dollars per month. Reporters and journalists were forced to take second and third jobs. Others simply took bribes.

In l992, the Moscow-published newspapers with the largest circulation in the former Soviet Union lost about 18 million subscribers. Pravda , the flagship paper of the Soviet period, shrank from 10.5 million subscribers in l985 to 337,000 in l993.

Other, more controversial papers, often focusing on "investigative journalism" and exposing corruption in both the public and private sectors, enjoyed peak circulation in the early l990s and rapidly declined or collapsed. The weekly, Argumenty I Fakty (Arguments and Facts), had over 33 million subscribers in l990, but 5.5 million in l994. Izvestia , which had adopted an independent path after the Soviet collapse, had reached a circulation of l0.4 million in l988 but withered to 435,000 in l994. Komsomol Pravda , had reached 22 million readers in l990, but collapsed to 87l, 000 in l994.

Not a single major daily exceeded l.5 million subscribers in l993, and most were under a million. By the summer of l995, only four newspapers could really be called Russian in the sense of having a national circulation: Trud ( Labor , the trade union paper), Komsomol Pravda , Argumenty I Fakty , and AIDS-Info , a paper oriented to young people. A number of leading Russian newspapers went bankrupt. Others sought support and financial aid from foreign media conglomerates, though these were often short-term relationships. Some papers became more dependent on local or regional government subsidies or reverted to state ownership. The l998 ruble crash destroyed what remained of the currency and the financial markets. Even more, it cut back or completely ended government support and subsidies to many media and television stations. Even before this, government was able to actually pay out only about 20 percent of the promised amounts they had committed to the media.

In l999 there were l5, 836 officially registered newspaper titles published in the Russian Federation. There were also 7,577 periodicals. Argumenty I Fakty remained the most popular magazine in Russia though its circulation plummeted from over 30 million to fewer than 3 million in 2000. Izvestia was down to 4l5, 000 in l999. Komsomolskaya Pravda had a circulation of 763,000 in 2000. Compared to l990, the total national circulation of newspapers by l999 was reduced to one-fifth, magazine circulation in the same period decreased to one-seventh.

In less than a decade, and far more rapidly than in the West, Russia evolved from its historic role as a "reading nation" to that of a "watching nation." In l999 overall audience for the print media was 80 percent while television got 95 percent of all Russian viewers and radio got about 82 percent. Thirty-six percent of all Russians found television as the most reliable medium, while only 13 percent define newspapers as reliable.

As of the early 2000s there were a number of foreign language newspapers, which mainly catered to the large foreign language communities, primarily in Moscow and St. Petersburg. Going back to 1930, the English language Moscow News was a KGB front paper for English speaking visitors in the city. After l99l it became a legitimate independent newspaper, appealing to tourists and business interests, along with The Moscow Times . Both were widely distributed in foreign hotels and businesses, and they offered a combination of political and business news plus tourist information. Since they carried a wide range of advertisements they were usually given away for free. The St. Petersburg Times performed a similar function in that city. There were also German and French publications, but these were dwarfed by the much larger Anglo-phone audiences. Moscow News had a Russian language circulation of about l20, 000 and an English language edition of 40,000.

Advertising helped support press independence, but it was largely concentrated in the big cities, especially Moscow and St. Petersburg, where most wealth and foreign investment were concentrated. Outside these cities, most newspapers tended to be in the hands of local political forces. With the collapse of the big national dailies, there was an upsurge in local and regional papers, some of which were considered quite good and very professional. But they too tended to be highly vulnerable to financial and political pressures, often from local and regional political forces. Private Russian investors or foreign partners have bought up some Russian newspapers and magazines. But in the late 1990s, the Putin regime seemed to have broken the power of private investors over the media.

Even more significant than the economic collapse of newspapers and their subsequent demise was the crumbling of public faith in the Russian media. In l990, a survey by the Commission for Freedom of Access to Information, a Russian NGO, found that 70 percent of respondents believed the media's reports. Six year later, a poll by the same organization found that only 40 percent trusted journalists. In 2000 the commission said the figure was l3 percent.

Economic Framework

Historically Russia lagged behind most of Europe, both in terms of economic development and even more, in individual living standards. The forced draft collectivization and industrialization of the l930s were achieved with staggering losses in life and great human suffering. They allowed Soviet Russia by 1941 to leap ahead in industrial terms to become the second greatest industrial power in the world, at least quantitatively. But devastating human and material losses in World War II, along with a grim determination to rebuild industry and the military first, left the average Russian far behind West Europeans and even further behind Americans.

Soviet Russia did manage to perform economic miracles both in terms of industrial production and in terms of keeping pace with the United States in the Cold War arms race. But the Soviet economy failed to deliver civilian consumption goods to satisfy the Soviet peoples. As Marshall Goldman wrote in l983, the Soviet Union largely won Khrushchev's industrial race with the United States, but it won the "wrong race." In l987, the Soviet Union produced twice as much steel as the United States, but in that same year there were 200,000 microcomputers in the country compared to 25 million in the United States. Russia produced enormous amounts of raw and finished goods, industrial products to satisfy the planners in Moscow not the Russian consumer.

At the same time, the Soviets had developed a first rate education system, a good and almost free medical system, and they provided something of a nation-wide welfare and full employment system, though admittedly there was a lot of "disguised unemployment." For many years the prices of necessities were kept artificially low and relatively stable in Russia with the countryside clearly subsidizing the urban population. Consumers were obviously starved for higher end quality products, and housing was in desperately short supply. The ubiquitous queues characterized the Russian consumer economy, reflecting both consumer goods scarcity and serious under pricing. According to research carried out in l987, some 83 percent of the population paid extra for goods and services outside the official distribution system; they were doing business on the black market.

The assumption in the West was that Yeltsin leadership of the Russian Federation only had to put Russia on the path to capitalism, privatize the enormous resources of the state, and give a push, and Russia would be on its way. This action proved to be a disaster.

In the European and U.S. traditions, capitalism and the press grew up almost together. Many of the great fortunes in the West were made when one individual (or a group of individuals) discovered a new product, market, or method of manufacture, iron and steel, oil, automobiles, or microchips. These were the success stories of Rockefeller, Carnegie, Ford, and Gates.

In Russia, by contrast, the nation had tremendous wealth already created by the blood, sweat, and sacrifices of the Russian people. With the collapse of the old Soviet Union, Boris Yeltsin and his inner circle largely distributed this wealth, especially natural resources, in the form of legal monopolies and trading privileges to various of his cronies and "insiders." The old restrictions and protections were simply thrown away without regard to consequences or consumer protection. Many old Communist Party apparatchiki (organization men and operators in the old Communist Party network) became rich and corrupt. Personal connections meant everything.

Removing price controls in 199l created inflation in Russia somewhat similar to the hyper-inflation of Weimar Germany in l923. A reckless banking system contributed to the collapse of the Russian ruble in l998. Both of these forces destroyed much of the nascent Russian middle class and impoverished almost all citizens on fixed incomes, that is, almost everyone over 55. The gross national product dropped sharply for most of the first decade of post-Soviet rule. However, a handful of Russians in the post-Soviet era become multi-billionaires, largely because of their personal connections to Yeltsin's Kremlin inner circle. In doing so, some acquired enormous amounts of wealth from the Soviet state for pennies on the dollar, sometimes not even pennies.

The big losers were the Russian people, the vast majority of whom eke out livings in factories, on farms, or, especially women, as small time traders on street corners, selling food, pirated videotapes, often in the harshest weather. Many took second and third jobs just to pay for rent and food. Begging on the streets and in the Metro was a professionalized industry in Moscow.

Between l99l and l998 there was an economic revolution and a "new stratification" in Russian society. According to a Finnish source, ( Nordenstreung , Russia's Media Challenge) the employed population dropped from 71 percent to 58 percent; pensioners went from l9 to 28 percent; the unemployed climbed to 10 percent; students from 7 to 3 percent; and housewives rose from 4 to 5 percent of the entire population.

In the early 2000s Russia's gross domestic product was about $3,000 per capita per year while that of the United States was about $32,000 per year and Germany's (even allowing for the depressed former Eastern zone) was about $23,000. Former Soviet satellites had a noticeably higher income level: the Czech Republic, an average income of $ll,700; Hungary, $7,800; and Poland, $7,200. But these statistics reflect comparative income levels that go back to the nineteenth century. After World War II Russia was not able to substantially improve its living standards in comparison to other countries, for example, Germany, Japan, China, and much of East Asia. Living standards for most Russians dropped sharply.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, there was little sense of authentic free enterprise in modern Russia and little real sense of competition. In the Western world, advertisers spend tens of billions of dollars on ads of every kind, amounting to about $200 per person per year in the United States. They spent about $2 per person per year in Russia. The press tended to be small in size and limited in its number of pages. Advertising played a small role in most newspapers, though in l995 both newspapers and television claimed they derived 30 to 50 percent of their budgets from advertising.

While one is aware of advertising in the Russian media, it hardly plays the decisive role it does in media empires of the West. Each media empire tends to have its own corporations and advertisers. The only strict rule is that they do not criticize the media owners or their views or political sponsors.

There have been a few high profile, high-spending advertisers. Usually these were for luxury items such as foreign cars, clothes, chocolates, or perfumes. One of the few notable Russian exceptions was the MMM pyramid scheme, which in l993 and l994 was the most frequent advertiser on Russian television, guaranteeing almost instant riches. Millions of naive Russians put their life savings into the stock, which rose from about a dollar to over 50 before the inevitable collapse. Interestingly, the slogan of MMM was "the government has betrayed you, but MMM never has—and never will!" A depressed economy directly affects the media.

On the other hand, electronic media in many ways reflects the New Russia. Russian broadcast advertising is slick and sophisticated, certainly a match for its Western counterparts. Russian advertising tends to be concentrated at the beginning and end of most programs, allowing viewers to enjoy most programs with less interruption. At the same time, many Russians, especially those living outside Moscow and St. Petersburg, criticize television with its glitzy advertising, claiming it creates a far higher imagined living standard than most Russians can possibly afford and thus produces what in the West used to be called a "Revolution of Rising Expectations." This induced hopefulness went a long way towards undercutting

Russia's greatest foreign exchange earners were exported oil and natural gas, which earn about 40 percent of all exports. As of the early 2000s, the country was the second largest oil and gas exporter in the world. Though not a member of OPEC, Russia did within limits cooperate and follow OPEC guidelines. Base metals earned another 20 percent. The biggest imports included foreign (luxury) automobiles and electronic goods and machinery of every description. Contrary to the United States, Russia did enjoy a massive mercantile balance of payment surplus (exports of $80 billion; imports of about $50 billion). This surplus enabled Russia to make huge interest payments on its massive foreign debts and to pay for massive imports of new technology from the West.

Nonetheless, many factors contributed to Russia's poverty and economic chaos. In part it resulted from Russian capitalists and insiders whose self-serving actions alienated the new regime. Some of these opportunists lived in safety and luxury in London or Madrid or in the United States. Following allegations of misuse of International Money Fund (IMF) funds and loans, an audit was conducted of the Central Bank. Auditors revealed in February, l999, that the bank had diverted some US $50 billion in hard currency reserves over a five-year period into an "offshore" company, which invested and managed the assets for the personal gain of bank staff provoked outrage.

After considerable time of unrestricted capitalism, many Russians were thoroughly disillusioned. Perhaps, they did not want a return to Soviet style Communism, but they seemed more than willing to return to an autocratic government with less free enterprise and more willingness to provide minimal economic and social needs.

To some extent, the Putin regime began to move in the more traditional Russian direction. The economy turned around and began to grow strongly in 2000 and 2001. Total foreign investment grew by 23 percent, mainly in the oil industry. Inflation remained high, about l8 percent per year, but it was far more manageable than earlier. Average wages increased to $l43 (4,294 rubles) per month compared with $89 (2,492 rubles) per month in 2000. Approximately 27 percent of citizens continued to live below official monthly subsistence level of $52 (l,574 rubles) per month. Official unemployment remained at about 10 percent, though the real rate of unemployment is much higher. There was a five-fold increase in tax revenues from an admittedly very low level in l998 to 2002. Part of that increase reflected better incomes, a new flat tax rate of 13 percent, and perhaps much more rigorous tax collection. But above all, it demonstrated far more faith in the country, the new government, and hope for the future. Projections in 20002 forecasted that the Russian economy would grow by about 3.5 percent from 2002 through 2005.

In a poll conducted by the Russian Public Opinion Center in 2002, just 5 percent of the respondents chose European society as a model for Russian development and 20 percent favored a return to Communism. Sixty percent said the country should follow its own unique path of development. Another majority, 70 percent, said above all, Russia needed a strong leader.

In the l930s and l940s Marxists around the world often explained embarrassing events in Russia by saying that the Soviet Union was not practicing "real Communism." Western apologists for the Yeltsin years explained the corruption and economic changes in Russia as "not real capitalism." Still, there seemed to be a feeling that Russia had turned the corner and economic conditions were beginning to improve.

Press Laws

On paper, the Russian press and media enjoyed some of the strongest legal protections in the world. Section 5 of Article 29 of the new Russian Constitution of l993 explicitly provides: "The freedom of the mass media shall be guaranteed. Censorship shall be prohibited." But it is easier to make laws than to interpret or enforce them.

Of much greater day-to-day significance is the Law Concerning Mass Media, significantly signed by Boris Yeltsin on December 27, l99l, two days after he took office as president of the Russian Federation. Article I of the law commits itself to "freedom of mass information." Article 3 expressly prohibits censorship. At the same time, all mass media in Russia must register with the Ministry of Press and Information (Article 8), which implies non-registered media cannot operate in Russia. Sometimes overridden, this law nonetheless has enormous potential for misuse. Courts have authority to prohibit publication or other function of a medium, for violation of Article 4, "The Abuse of Freedom of a Mass Media." While there is nominal freedom of the press, Russian law leaves courts and government the option to crack down on abuses, to be determined at their own discretion.

Elaborate discussion is made of grounds for application and Article l6 explicitly states:

The activity of a medium of mass information can be stopped or suspended only by a decision of the founder or by a court acting on the basis of civil legal proceedings in accordance with a suit of the registering organ or the Ministry of Press and Information of the Russian Federation.

The same kinds of laws apply to broadcasting and the license to broadcast. Under Article 32, a broadcast license can be annulled: if it was obtained by deception; if licensing conditions or a rule government dissemination of programs … have been repeatedly violated and on the bases of which (two) written warnings have been made; and if the commission for television and radio broadcasting establishes that the license was granted on the basis of a hidden concession.

Given the political and economic realities of Russia at the time, virtually every broadcast license granted may have violated one or more of these prohibitions.

Still, there is a positive and liberal spirit in the mass media law, which encourages openness. Article 38 provides that "Citizens have the right to receive timely and authentic information from a medium of mass information about the activity of state organs and organizations; society bodies and official persons." Article 43 offers a "Right of Refutation," roughly the Russian equivalent of the U.S. Equal Time laws. Article 47 of the Mass Media Act actually provides for a Journalist's (Bill of) Rights. These include the right to request and receive information and the right to visit state bodies and organizations and to be received by official persons. Newspersons have the right to copy records and to make records. Article 49 lists journalists' obligations, and Article 50 explicitly states that "journalists have the right to use 'hidden' recordings." Article 58, entitled "Responsibility for the Limiting of Freedom of Mass Information" warns that any government agency which effectively censors mass media "entails immediate cessation of their funding and liquidation on the basis of the procedure provided by legislation of the Russian Federation." Article 59 again specifies, "The abuse of a journalist's rights … entails criminal or administrative liability in connection with the legislation of the Russian Federation." Clearly, the Mass Media Law outlines openness and fairness. Its practical application is another matter.

A separate Press Law for Russia, published on February 8, l992, paralleled the Mass Media Law. The law gave private individuals and businesses the right to establish media outlets. It anticipated the adoption of a separate law regulating television and radio broadcasting. But this separate law was never adopted, leaving all kinds of legal problems for the actual establishment of the granting of broadcast licenses. Inevitably there was room for political favoritism and bribery.

Censorship was again forbidden, but certain kinds of speech are prohibited, especially those calling for changing the existing constitutional structure by force; arousing religious differences, social class, ethnic differences; and disseminating war propaganda. The vagueness of the Press law left room for all kinds of defamation and libel suits by public figures. Famed right-wing, nationalist Vladimir Zhirinovsky alone was reported to have filed nearly one hundred lawsuits from l993 to l995.

A number of laws were designed to supplement the Law of Mass Media. The Statute on State Secrets, adopted by the parliament on July 2l, l993, defined a state secret as "information protected by the state in the area of defense, foreign policy, the economy, intelligence … the dissemination of which can damage the security of the Russian Federation." Like similar U.S. laws and the British Official Secrets Act, it made disclosure of state secrets a crime.

The l994 Federal Statute on the Coverage of the Activities of State Agencies in the State Media was important because a large portion of the mass media in Russia belongs to the state bodies of different levels. The State Duma on January 20, l995, adopted the Federal Statute on Communications, which established the legal basis for activities in communications and confers upon organs of state power the authority to regulate such activities and determines the rights and obligations of entities involved in communications.

Article l5l of the Civil Code and Article 43 of the Statute on the Mass Media placed responsibility for proving the correctness of the information on the defendant (i.e., the journalists or editors of the outlet). This requirement created problems for publications and broadcasters, many of whom had to prove the accuracy of allegations in order to avoid liability.

The Federal Statute on the Economic Support of District (Municipal) Newspapers, adopted by the State Duma on November 24, l995, provided subsidies to the newspapers. Again, this law had enormous significance both because of the appalling economic conditions in Russia and because of the general belief that once the government begins to subsidize local papers, it has tremendous leverage over the editorial and news policies of local papers. In January, 2001, the parliament passed a new law which federalized this support and thus gave control (both financial and by implication editorial) directly to Moscow.

At the beginning of the 2000s, Russia still lacked a statute on television and radio broadcasting. The statute On the Mass Media did allow for the government to shut down or suspend a media outlet if the state believed it violated the law. According to this statute, the government must issue two written warnings within a given year, and then, if violations persist, it is obliged to go to court for an order to close the outlet. The l998 statute On Licensing of Certain Types of Activity provided for an annulment of a license to broadcast by a court decision without any warnings of the licensing body. The statute allowed the licensing body to suspend for up to six months a license if it believed that there were "violations of conditions of the license that could be harmful to the rights, lawful interests, morals and health of the citizens, as well as to the defense and security of the state."

On July 25, 2000, the Ministry of Communications issued a decree On the Order of Implementation of Technical Means of Providing the Operational-Investigative Measures on Telephone, Mobile and Wireless Communication Networks regulating the Implementation of the so-called System for Operational-Investigative Activity (SORM, by Russian acronym). The technical means enabled security services to collect information from security networks and allowed access to the contents of personal communications of any form including e-mail messages. Ironically, the decree obliged communications service providers to install at their own expense relevant equipment to assist security services in conducting investigations. This legislation understandably upset media groups, civil libertarians, and journalists.

Russian authorities and courts chose a flexible interpretation of these laws without the protections for which journalists had hoped. It must be said, however, that many of the media and especially broadcasters got their licenses originally by supporting the Yeltsin government, thus bending Russian media law in the first place.

There is no tradition of an independent judiciary in either Soviet Russian history or in the post-Soviet period. Nevertheless, Russia's Supreme Court in February, 2002, struck down an unpublished l996 military secrecy law that was used to convict of espionage and treason the journalist Grigory Pasko when he exposed to Japanese sources the Soviet-era navy mishandling of nuclear waste. The implication is of some independence for the Russian judiciary at least in the most blatant cases of injustice.

Censorship

Censorship has a long and honorable tradition in both Russian and Soviet history. An early instance occurred when Alexander Radischev published his pioneering expose of social conditions and injustice in Russia, Journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow , in l790. Catherine the Great (1729-96), appalled by the excesses of the French Revolution, saw Radischev as a dangerous radical. She originally sentenced him to execution and later reduced the punishment to ten years in prison.

Alexander I (1801-25) favored a "progressive" censorship policy, and Russia passed its first modern censorship law in l804. But the administration of Nicholas I (l825-55) epitomized the harsh, stringent censorship policy of Old Russia. Pushkin got in trouble with Russian censors, as did Dostoyevsky and Turgenev. Ironically, Russian censors approved the writings of Karl Marx, feeling that they were "too boring to be dangerous."

Censorship policy and laws were modified under Alexander II (l855-8l), allowing the birth of Imperial Russia's popular press not long after it developed in the West and allowing Russian literature to enter its truly golden age. Censorship was almost entirely abolished with the reforms that followed the Revolution of l905.

Lenin and the Bolsheviks restored strict censorship after they seized power. The Decree of the Press of October 28 (November 10), l9l7, basically banned all anti-Communist publications. Lenin believed the press "must serve as an instrument of socialist construction." Originally censorship was to be abolished with the end of the civil war, but in l920 Lenin refused to annul the decree, claiming that unrestricted freedom would "help monarchists and anarchists" and weaken the fragile Bolshevik regime.

In l922, Glivat was set up, the Main Administration for Safeguarding State Secrets in the Press (Glavnoye Upravelenie po Okhrane Gosudarstvennykh Tayn v Pechati) under the Council of Ministers. Elaborate controls were established and Glavit functionaries were provided with a manual (affectionately called the Talmud by working censors) containing long, continually updated lists of prohibited materials. Failure on the part of the censor to detect publication of a state secret could lead to eight years in prison.

With Stalin's accession in l928, censorship clamped down even harder and socialist realism became the literary form of the day. Soviet writers tried to go unnoticed, and there was a great deal of "writing for the drawer," that is, putting manuscripts away in hopes of a future, more tolerant day. Soviet readers, especially the politically astute, developed high skill in translating the euphemistic language of the Soviet press. Though Soviet press censorship eased after the death of Stalin, it remained in place almost to the end of the regime. State security was a prime concern for the Soviets, and its constituent elements were broadly construed.

Boris Pasternak (l890-l960), arguably the greatest writer of Soviet Russia, was the most famous victim of its censors. His novel, Dr. Zhivago , was rejected by a leading Moscow monthly in l956 because it "libeled the October Revolution and socialist construction." The manuscript was smuggled out of Russia, printed by an Italian publisher and became a worldwide best-seller. Pasternak received the Nobel Prize for literature in l958, which he was forced to refuse for political reasons.

The Soviet Criminal Code had elaborate provisions to guard against undesirable materials and statements. Article 70 warned against "Propaganda and agitation, which defame the Soviet state and social system," Article 75 punished "Divulgence of State Secrets," and Article l30 punished "circulation of fabrications known to be false which defame another person." The fact that in all, the censorship office employed 70,000 people across the Soviet Union, gives some idea how much importance the Soviets attached to censorship.

Until l961, the Soviets practiced an overt policy of pre-publication and pre-broadcast censorship of foreign correspondents' reports. Everything had to be cleared through the foreign correspondents' censorship office or it was not transmitted out of Russia. After l96l, and on into the l980s, the Russians adopted a policy of self-censorship which allowed correspondents to send out almost anything they wished, but with the knowledge that if they stepped over the line, they would be deported immediately.

A key part of Mikhail Gorbachev's program was glasnost (openness). Like his mentor, KGB Chief Yuri Andropov, Gorbachev realized how much the nation was being hurt by its closed society mentality and the resulting hunger for information. Glasnost was essential for his even more fundamental plans for perestroika , the complete restructuring of the entire Soviet economy. Thus, with the passage of Gorbachev's Press Law of August, l990, Glavit and official censorship came formally to anend. The l993 Media Law expressly prohibited censorship and protected the right "to gather and distribute information." However, the law had enough nuance to allow politicians, bureaucrats, and media bosses to influence those who articulated the news.

Boris Yeltsin was at first a great champion of the free press and free media. He became bitter, however, about those who criticized his administration and later his conduct regarding the war in Chechnya. In September, l993, during his attempt to close down the Duma and the storming of the White House, censorship was reinstated. Based on the state of emergency that Yeltsin had declared, a presidential decree closed down the 10 most important opposition papers (mainly Communist).

President Vladimir Putin made known his dissatisfaction with press reporting of the war in Chechnya and other issues. He was embarrassed by the media when it showed him vacationing at a Black Sea resort while the Russian nuclear submarine Kursk sank in the Arctic Ocean with 118 crew aboard. After that, he became more media and public relations conscious. He urged the media people to use more self control in their reporting.

After coming to power in January 2000, Putin reined in Russia media and their freewheeling reporting styles. Under Putin, it was more difficult for the press to go into Chechnya than it was in the first war. Terrorist bombings against civilian apartments in Moscow and other places made the Russian public far less tolerant of the Chechens than they were in the first round of fighting.

In March of 2000, in his first annual address to members of the Russian Duma, President Putin warned, "Sometimes … media turn into means of mass disinformation and a tool of struggle against the state." In September 2000, he signed the Doctrine of Information Security of the Russian Federation, which offers general language on protecting citizens' constitutional rights and civil liberties but also includes specific provisions that justify greater state intervention. For example, the doctrine gives much leeway to law enforcement authorities in carrying out SORM (System of Ensuring Investigative Activity) surveillance of telephone, cellular, and wireless communications.

The case of Vladimir Gusinsky illustrates the state suppression of the media. In April, 2000, government security officers raided the offices of Media MOST, the flagship media empire of Gusinsky whose spokesmen had been especially anti-state. Media MOST was deeply in debt to a number of other businesses, most of all GASPROM, the huge state-owned natural gas monopoly. At the same time Gusinsky was charged with embezzling funds in a privatization deal. Supposedly Gusinsky was secretly offered a deal by the state prosecutor: if he sold his shares of Media MOST to Gazprom, he would be set free. Gusinsky signed the deal. Claiming later that he signed under duress, Gusinsky subsequently went into exile in Madrid. Spain refused to honor an Interpol warrant for him issued in Russia on fraud charges. Later he moved to New York City.

In the meantime, litigation began to determine who should control the Media MOST empire. In early April, 2001, Gazprom finally won the litigation and soon appointed its own men to run NTV. Eventually, new managers took over the station. For a while NTV personnel fled to TV-6, controlled by Boris Berezovsky. But when TV-6 personnel refused to break off their connections with the exiled tycoon in London (or at least the Ministry of Press said they did not) government forces closed this station as well.

The Media MOST takeover sent a clear message across Russia that political power and the government controlled the media. A large proportion of Russians admitted that they favored tightening government controls and expanding government authority in every sphere. After years of almost unlimited freedom, many Russians seemed eager for a return to authoritarian controls and benefits.

As an illustration of this trend, the Glasnost Defense Foundation estimated that government agencies brought several hundred lawsuits and other legal action against journalists and journalistic organizations during 2001, the majority of them in response to unfavorable coverage of government policy or operations. During the year, judges rarely found for the journalists; in the majority of cases, the government succeeded in either intimidating or punishing the journalist.

Rulings upholding libel and other lawsuits against journalists served to reinforce the already significant tendency towards self-censorship. Many entry-level journalists in particular practiced self-censorship. For example, in April, 2001, Yuriy Vdovin, a prominent St. Petersburg-based media freedom activist, stated at a Moscow conference: "young journalists are particularly vulnerable to self-censorship, because they are less protected from mis-treatment by authorities. If a young reporter loses his job for political reasons, his chances of finding a new one are much lower than those of his older, more established colleagues. It is also more difficult for a young, unknown journalist to rally public attention and support." On February 27, 2002, the editor of Russia's most influential radio station, Echo Moskvy, announced that he and dozens of other journalists were quitting rather than work for a news outlet that was becoming a voice of the state.

State-Press Relations

Russian state-press relations almost came full circle in the last two decades of the twentieth century. In the l980s, the press and other media were under the tight control of the Communist Party. Control and supervisions were exercised by two departments: the International Information Department (IID) and the Propaganda Department of the Communist Party Central Committee. Most Soviet media, especially high profile newspapers, such as and Izvestia , were understood to be more than mouthpieces for the Communist Party and the Soviet state. The electronic media were administered by the State Committee for Television and Radio and also under the Council of Ministers.

In the absence of an independent press, dissidents at great personal risk often put out or contributed to privately circulated samizdat publications. Beginning in the late l970s more and more dissidents achieved recognition. Inthe l980s, they began to gain more respect and enjoy some tolerance. At the same time, some younger establishment journalists began to show more independence. Both elements played a major role in helping discredit and undermine the Communist Party and the Soviet state. While Gorbachev at first favored an independent press, as time went on he felt more and more it was irresponsible, mainly being used by anti-Soviet forces to embarrass the system and question its legitimacy. Far too late, he began to support those conservatives in the regime, who wanted to rein in independent journalists.

The years l988-92 were seen as something of a "breakthrough period" for the independent Russian press. Scandals were exposed; the dictatorship was undermined. The attempted putsch of August, l99l, was poorly planned and miserably executed. The independent press and the apathetic military played decisive roles in dooming the attempted revolution. At the same time, the television image of Boris Yeltsin standing on a tank, appealing to the Russian people to oppose the coup doomed the Soviet state and made Yeltsin an icon.

For the next two years the press and other media in Russia saw themselves as the country's saviors and decisive instrumentalities of democracy. The economic crisis and collapse reduced support for newspapers and other media. Resentment began to build between the Yeltsin administration and the Russia press over the reporting of corruption and the Chechnyan War. Still overwhelming media support went to Yeltin in the l996 elections, partly because of financial self-interest by various tycoons and media bosses and partly because the media feared a Communist victory would mean a return to censorship and retribution. The media, especially television, played a decisive role in re-electing Yeltsin, against overwhelming odds and economic problems.

But soon after the Yeltsin victory, increasing bitterness broke out between the state and the press and electronic media. Part of it was undoubtedly the inevitable disappointment and quarrels over the sharing of the election spoils. As soon as Yeltsin was re-elected, he began to shed some of his old media supporters. A series of media wars broke out between Boris Berenovsky and Gusinski and between both of them and some of the closest assistants to Yeltsin over claims that promised pay offs Pravda and appointments were not being made. Many of the media empires and independent magazines and television stations began to fold. Several of the media lords and business leaders who lost their shields of Kremlin protection, wisely began to leave Russia.

The appointment of Prime Minister Vladimir Putin, former head of the Federal Security Service (formerly KGB) on New Year's Eve Day, 1999, accelerated the deterioration of state-press relations. Putin was clearly upset by the liberalism and irresponsibility (and in his mind, anti-patriotism) of the press and wanted to curb its excesses.

As of 2001, the government owned nearly one-fifth of the l2,000 registered newspapers and periodicals in the country and exerted significant influence over state-owned publications. The government owned 300 of the 800 television stations in the nation and indirectly influenced private media companies through partial state ownership of the gas monopoly Gazprom and the oil company Lukoil, which in turn owned large shares of media companies. The State owned two of the three national television stations (somewhat akin to networks in the West) outright, Russian Television and Radio (RTR) and a majority of Russian Public Television (ORT). It also maintained ownership or control of the major radio stations Radio Mayak and Radio Rossii and news agencies ITAR-TASS and RIA-Novosti. The Government owned a 38 percent controlling stake of Gazprom, which in turn had a controlling ownership stake in the privately owned NTV. In April, 2001, Gazprom formally took over NTV because of unpaid debts.

At the regional and local levels, local governments operated or controlled a much higher percentage of the media than in Moscow; in many cities and towns across the country, government-run media organizations were the only major source of news and information. As a result in many media markets, citizens received information mainly from unchallenged government sources. In January 2001, Putin signed a law transferring control of government subsidies for regional newspapers from local politicians to the Press Ministry in Moscow. The New York based Committee to Protect Journalists claimed law affects 2,000 subsidized newspapers across Russia and would further centralize Moscow's control. The committee further stated that this control was especially true in the provinces where papers and broadcast media depended on local administrations for everything from floor space to computers.

In April 2001, the majority stockholder won a suit to close down the heavily indebted Segodnya (Today) newspaper, the flagship of the Gusinsky media empire. At the same time, the majority owner replaced the entire management and reporting staff of Itogi (Total) magazine, which had been owned by Gusinsky and which for several years had had a relationship with Newsweek . In May 2001, procurators raided the offices of the radio station, Ekho Moskvy, the only profitable Media-Most property and the most popular and independent station in Russia. They were supposedly searching for incriminating financial documents. The action frightened away advertisers for a while, which may have been the intention, but Echo Moskvy continued to operate independently for several months. But on February 27, 2002, the editor of the station announced that he was quitting rather than work for a news outlet that was becoming simply another voice of the state.

Increasingly, the press and electronic media were seen as mouthpieces for the Putin regime and the more independent press was seen as withering under the pressure of the state. Nonetheless, the situation was still far freer than in Soviet days, but state-press relations had returned almost completely to the conditions of two decades earlier.

Attitudes toward Foreign Media

In the Soviet period, most Russians' attitudes towards the foreign press were a mixture of curiosity, suspicion, and fascination. As time went on, Soviet Russia opened, and more and more foreign press was allowed in, including Western cameramen. By the late l980s, after the Helsinki Accords, the Western media were almost revered and imports, especially electronic equipment (usu-ally made in Japan) were automatically seen as inherently superior to Russian products. Even before Gorbachev's glasnost campaign, Soviet television began to adopt Western style news formats. Gradually the jargon of the Stalin/Brezhnev era was dropped and many Western terms began to creep into the media vocabulary, especially terms such as skandal .

With the breakup of the Soviet Union came a flood of Western products, Western newsmen and Western programs to Russian television and movies. Tourism and foreign media coverage skyrocketed in post-Soviet Russia. Tourist numbers grew from about 5 million in the early l990s to 21 million by 2000. In 2002, the Russian people were far more used to tourists and foreign media than they were just a few years before.

In the Soviet period, foreign news and the international situation seemed to be the primary focus for most Russian readers and television viewers. This focus was the result of deliberate Soviet policy, confrontation with the West, and a little sense of the forbidden fruit of the unknown West.

When Western programs and information began to flow into Russia they were well received. For a while Russians were wildly enthusiastic about the cornucopia of foreign programs and films that flooded the Russian media, especially foreign programs on Russian television. In late l993, the top 10 programs in Russia included Santa Barbara , Field of Miracles , and a Mexican soapopera, Just Maria . Later, enormously popular Mexican soap operas included The Rich Also Cry and Wild Rose were added to the list. Within a week after the movie opened in New York City, one could buy reasonably good tape copies of Titanic for seven U.S. dollars on the streets of Moscow. Almost every Western movie was pirated and dubbed within a few days in Moscow. Russia did pass the l993 Copyright Statute to respond to foreign claims of piracy but seemed to do little to enforce it. In any case, Russian viewers soon got used to these novelties, and as Russian television began to create its own soap operas, focusing on Russian problems, attention switched to them.

While foreign correspondents were tolerated, sometimes even respected, the Russians are amazed and bothered that so many foreign correspondents were assigned to Russia who did not speak Russian and who seemed to have not the slightest appreciation of Russian history or Russian culture. Russians also were amazed by how brief foreign visits tended to be and then to see these journalists on television broadcast from the West, claiming to be experts. Russians suspect Westerners who seem satisfied with brief interviews. They are also troubled by the seemingly superficiality and artificial friendliness of many Westerners, especially Americans. Russians tend to be far distant and slower to open to others and more committed in their relationships than foreigners seem to be with them.

After the Cold War ended, generally foreign correspondents were well treated and well respected, providing they played by Russian rules. They were forced to get special permits to visit certain areas of Russia, most of all in Chechnya; there the Russian military often suspected them of biased reporting and did not make getting permits easy. If correspondents leave, and they have been too critical of the situation in Russia, they may find it very difficult to return. But the Russian are loathe to carry this policy too far. They are anxious to have Russian correspondents accredited overseas, and journalists and their accreditation are often based on a system of quid pro quo .

In April 2002, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty announced it would start broadcasting to the North Caucasus region in Chechen, Avar, and Circassian. Russian officials warned that they would monitor the broadcasts and might take away its license if they showed a pro-Chechen bias. One Russian official warned that "members of radical Chechen groups" might use the radio service to encourage extremism.

New Agencies

The old Soviet Union had two news agencies. Telegrafnoyue Agentstvo Sovietskovo Soyuza: Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union (TASS) and Agenstvo Pechati Novosti (APN, the News Press Agency). For all practical purposes TASS was the official press agency of the Soviet Union. It was created in l925 and eventually developed into one of the largest international wire services in the world. It had news bureaus and correspondents across the Soviet Union and in over l00 countries around the world. While it was very extensive, it suffered from serious handicaps, as its news was heavily dependent on Moscow's interpretation of events, and often this dependency involved bitter arguments among editors and even inside the Central Committee of the Communist Party. As a result Soviet news often lagged behind that of Western sources and agencies.

Following the break-up of the Soviet Union in l99l, TASS was reorganized into two branches: the Information Telegraph Agency of Russia or ITAR, reporting on news inside Russia itself; and the Telegraph Agency of the countries of the Commonwealth or TASS, reporting on news of the other countries of the Commonwealth of Independent States. In addition, there were a number of newly created agencies including Federal News Service (FNS), Inter-fax, Post factum, and the Russian Information Agency-Vest, which collaborates with foreign press, and publishing organizations in 110 countries around the world. Interestingly while ITAR-TASS maintained a vast international network, almost all foreign news and reporting came from Western sources and networks. Over a 30-day period between December, l992 and January, l993, of l98 foreign news items, only 48 were written by Russian correspondents and l50 were translations from Reuters, Associated Press, or France Presse.

For foreign correspondents in the Soviet era, Moscow was one of the most frustrating assignments in the world. Conditions were harsh and the weather, especially in the winter, could be bleak. Censorship was frequent and often heavy-handed and the city itself was hard to live in with little outside enjoyment. There was always a real danger that foreign correspondents could run afoul of KGB machinations or worse, would compromise their news sources.

As of 2002, however, Moscow was often considered one of the "plums" for foreign correspondents. It was a far more livable and exciting city than it used to be, though winters could still be a challenge. There was certainly far more food, housing, and entertainment than ever before, and there was far more contact with other foreigners and with the Russian citizenry. As of May 2002, there was almost no censorship of any kind on foreign correspondents or on foreign news bureaus. Over 40 foreign news bureaus maintain offices in Moscow, from Agence France Press (AFP) to China's Xinhua (New China) and Korea's Yonhop agencies.

Broadcast Media

Lenin was one of the great readers of history but he was also one of the first world leaders to recognize the immense potential of radio and film for communication and propaganda. Years of exile in Siberia made him painfully aware of the enormous distances of Russia. In l922 he wrote to Stalin about the possibility of using radio to transmit propaganda over thousands of miles. In l925 the first short-wave station in the world began broadcasting from Moscow's Sokolniki Park.

At the same time ever-greater resources were put into motion pictures, both for home consumption and for foreign export and propaganda. Sergei Eisenstein's films, Strike (1924), Battleship Potemkin (l925) and October or Ten Days that Shook the World (l928), all showed the artistic and polemical power of the new medium in general and Soviet film in particular.

Radio dominated the early Soviet period. Almost all factories, collective farms, and eventually apartments and homes had basic Soviet-made receivers with selectively set tuning so they could only receive prescribed Soviet stations. Over these receivers in June, l94l, a broadcast announced Nazi Germany's invasion of Russia. Subsequently, it was Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov, not Stalin, who went on the radio to reassure the Soviet peoples. In March, l953, Radio Moscow announced the death of Stalin.

Foreign radio broadcasts played an important role in Russian listening habits, even though most Soviet era radios were made only to receive domestic broadcasts. "Enemy voices" (vrazhskie golosa) gave Russian listeners not only far more understanding of what was going on outside Soviet Russia but often inside as well. One survey carried out between l977 and l980 indicated that perhaps as many as one-third of the Soviet adult population "was exposed to Western radio broadcasts in the course of a year, and about one fifth in the course of a typical week."

During the August, l99l coup attempt, when the Communist hard-line Emergency Committee attempted to take control of the press, television and radio, people turned to foreign radio stations for news. Many were surprised to hear that President Gorbachev himself listened to enemy voices when he was in custody in the Crimea.

He confided the following in his book, The August Coup :

The best reception was from the BBC and Radio Liberty. Later we managed to pick up Voice of America. My son-in-law Anatoli managed to listen to a Western station on his pocket Sony. We started to collect and analyze the way the situation was developing.

Television was first developed in the United States in l928. The Nazis actually broadcast part of the l936 Olympic games over television to the rest of Europe. Experimental television transmission in Soviet Russia began in the l930s. By l950 there were 10,000 television sets in all of the Soviet Union; by l960, there were almost 5 million. (The comparable American figures were 700,000 sets in l948; 50 million sets in l960.)

In l960 one of the world's largest television towers in Moscow's Ostankino neighborhood went into operation. At the same time television production and accessibility were dramatically increased in the l960s. By l988 there were 8,828 television broadcasting stations in the Soviet Union, covering virtually the entire country. There were 90 million television sets in the USSR.

Television had enormous influence on contemporary Russia for three reasons: 1) the enormous distances of Russia made it the only effective communications medium; 2) with the implosion of the Russian economy in the l990s and the decline of printed media, television broadcasts were largely a free commodity and free entertainment, hence supremely important to Russian consumers; and 3) while Russians in general were much more a reading public than Americans, working class Russians remained overwhelmingly dependent on broadcast media and especially television for their news.

These patterns were clear even in the Soviet period; hence they brought tremendous emphasis on television production and programming. In spite of the importance the Soviets put on the medium, most Communist programming (like the press) was largely wooden, stilted, and two-dimensional. One of the few exceptions was the evening Nine O'clock News program which even in the Soviet period was professionally done and received enormous attention. It became one of the hallmarks of the Soviet television industry and something of an icon for television watchers across the land who habitually gathered around the television set at night.

Gorbachev was clearly the first television secretary-general, just as Kennedy had been the United States's first television president. Undeniably, under Gorbachev, Soviet television programming vastly improved. In l986 and l987, glasnost allowed more liberal and more progressive shows on Soviet television: Give Me the Floor , The World and Youth , Cast of CharactersTwelfth Floor ,and above all, Vzglyad (Glance or View) which was something of a Russian version of CBS's Sixty Minutes , and which specialized in the same kind of exposes, became overwhelmingly popular television shows.

In May l989, for the first time in history, the entire Congress of People's Deputies was broadcast live on Russian television so unlike the previously carefully edited wooden shots and sound bites. An enormous number of Soviet citizens watched these broadcasts with rapt attention, perhaps 75 percent a far greater number and percentage than their U.S. counterparts who normally see their national political conventions as unappreciated interference with regular programming.

Under Gorbachev and then Yeltsin, Russian television came of age. Many television broadcasters, especially for news programs, became national personalities in their own right. A flood of new programs and "independent" stations came on the air, of widely varying quality, and there were a host of foreign programs that began to fill Russian airtime. Russians newscasters were far more inclined than their Western counterparts to give their personal views and their own personal interpretation on the news they were reporting. Many of the newscasters became celebrated personalities in Russia, which helped some of them launch political careers.

On September 2l, l993, President Yeltsin issued Decree No. l400 and suspended the Congress of People's Deputies and ordered new elections. Parliament in the White House ordered Yeltin removed from office. Their supporters then tried to seize the national broadcasting center and tower at Ostankino and ultimately failed. Eventually pro-Yeltsin military forces attacked and seized the White House. The critical factor here is that both sides recognized the decisive importance of television in modern Russian politics.

Over 700 private television stations emerged in Russia after l992. As of 2002, there were 800 television stations in all of Russia, including 300 owned partly or completely by the state and 500 private stations. At the end of l993, there were only two channels with national audiences, Channel One (Ostankino) and Channel Two (Russian Television), both owned and managed by the Russian state.

The Yeltsin government decided to allow the de facto privatization of Channel One in l995. The state retained control of 5l percent of its shares while a consortium of banks and industrial groups held the remaining 49 percent. The largest single private shareholder was Boris Berezovsky, a tycoon with Kremlin connections and the head of Logovaz, a conglomerate based on a car dealership. By the end of Yeltsin's second term, Berezovsky's media empire included control over television channels ORT (Channel One) and TV-6, newspapers Nezavisimaya , Novye Izvestya , and Kommersant , as well as a number of weekly magazines.

Vladimir Gusinksy started off as a theater director in the old Soviet days, who always had an interest in the media. He came to power through his connections with Boris Yeltsin but from the first he sought to build a vast media empire. He got control of NTV (Russian Public Television) in October, l993, and since it did not have a license to broadcast on a major national channel, Gusinsky avoided the license requirement by getting a presidential decree to broadcast. NTV was an overnight success. It played Western movies and sports and had the most professional and most reliable news coverage, both of events in Russia and the war in Chechnya. Gusinsky clearly supported Yeltsin in the l996 presidential elections, as were all private and state-owned television stations and virtually all printed media.

Many believed that without the media support, especially television, Yeltsin would have been defeated in the l996 elections by Zhuganov and the Communists. As apay off to Gusinsky, the government announced that NTV would be able to pay the same low program transmission rates that official government stations paid. Most other private, independent stations were outraged.

Even before the l996 election, Yeltsin had invaded the independence-seeking republic of Chechnya. The operation was a disaster. For the first time free and independent television, most of all National Television, actually got into Chechnya ahead of Russian armed forces and was able to expose the lies of official Russian reporting.

Independent Russian reporting in the first Chechnyan War had an effect in Russia similar to the U.S. reporting on the Vietnam War had in the States. The graphic pictures of human suffering on both sides largely cost Russia the war in the Russian hearts and minds at home back in the Russian homeland. More and more Russians asked why their husbands and sons were fighting in Chechnya and if it was worth the price. The shaky alliance supporting Yeltsin soon came apart, especially after the blatant jockeying for power and the Berezovsky-Gusinsky alliance lost out in bidding for another media group headed by Kremlin insider Panin and supported financially by billionaire George Soros.

With the appointment of Putin as president on December 3l, 1999, a series of furious battles broke out to control independent private stations. One after another, former Yeltsin cronies fled Russia for the West, and the remnants of their economic and media empires were either foreclosed or taken over by new government-controlled or government-sympathetic media forces.