Slovenia

Basic Data

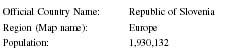

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Slovenia |

| Region (Map name): | Europe |

| Population: | 1,930,132 |

| Language(s): | Slovene, Serbo-Croatian |

| Literacy rate: | 99.0% |

| Area: | 20,253 sq km |

| GDP: | 18,129 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Daily Newspapers: | 5 |

| Total Circulation: | 341,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 215 |

| Number of Nondaily Newspapers: | 14 |

| Total Circulation: | 424,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 267 |

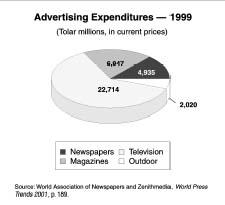

| Total Newspaper Ad Receipts: | 4,935 (Tolar millions) |

| As % of All Ad Expenditures: | 12.10 |

| Number of Television Stations: | 48 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 710,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 367.9 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 322,200 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 161.1 |

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 270,000 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 139.9 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 177 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 805,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 417.1 |

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 548,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 283.9 |

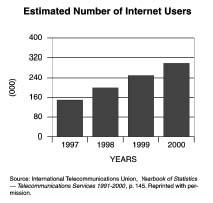

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 300,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 155.4 |

Background & General Characteristics

Slovenia is a democratic state in the former Yugoslavia that has fostered a liberal and diverse press. Compared to neighbors to the south, Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina, the Slovenian press has for centuries been fairly uncensored and unrestricted by government. During the period in which Slovenia was under communist rule, the press was still the most liberal among eastern-European nations. Since the country adopted its Constitution in 1994, the press has been guaranteed freedoms like those in Western democracies, although perhaps out of habit and tradition, media professionals continue to censor themselves.

Slovenia is a country of readers. In a population of nearly 2 million citizens, circulation for all printed media is around 6 million.

Nature of Audience

Slovenia's proximity to Italy, Hungary, and Austria make for a diverse population with many ethnic and linguistic influences. The official language is Slovene, which is spoken almost strictly by those who live in Slovenia, with the exception of pocket communities in Italy along the Slovenia border.

During times when Slovenia was occupied by the Turks in the 15th century, the Austro-Hungarian monarchy in the 19th century, and the Serbs in the 20th century, early newspaper pioneers established news presses strictly for the purpose of maintaining the Slovene language and culture. For a time in the 20th century, Austria annexed a large part of Slovenia, and the region joined the Kingdom of Yugoslavia during the Second World War. In 1941 the Liberation Front of the Slovene Nation was founded and began armed resistance against the German occupying forces. The Communist Party soon adopted the leading role within the Liberation Front, and at the end of the war the ethnic Slovenians were liberated. In 1943 the nation joined the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, and Slovenia was known as the Socialist Republic of Slovenia.

Slovenia gained its independence late in the 20th century. The movement for independence was first made in 1987 by a small group of intellectuals. The group made demands for democratization and resisted the Yugoslavian government after the arrest of three journalists from the Mladina , a political weekly.

In 1988 and 1989 Slovenia produced its first political opposition parties, and in 1989 demanded a sovereign state. In 1990 the first elections in Slovenia took place, and more than 88 percent of the electorate voted for independence. The country adopted its declaration of independence in June 1991, and the very next day the country was attacked by the Yugoslav Army. After a brief 10-day war, a truce was negotiated. In November of that year a law on denationalization was adopted, followed by a new Constitution in December. The country's liberal and relatively free press was credited as much for the successful

Slovenia is an educated, financially stable, and literate country. This is good for the newspaper industry as a whole. Slovenians are not only literate, but are well read and tend to get their news from more than one print source. In the 1980s Slovenia published more new titles per capita than any other European country. While Slovenia no longer boasts holding the record in publishing, its root of diverse publishing and avid readership are still strong.

Nearly one-third of Slovenian households are connected to the Internet, and 450,000 citizens are regular users of the Internet.

The country underwent a massive reorganization of its public school system in the 1990s to ensure its citizens could exercise their rights to free education. The average number of years Slovenians attend school is 9.6 and compared to similar nations ranked behind Austria, Switzerland, Belgium, Denmark, Israel and Hungary.

The country's stable economy and government has enabled Slovenia to successfully transition from communism to a capitalist democracy easier than the other former Hungarian states, Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina. This strong economy has also enabled the print and broadcast media to stay afloat financially, as domestic and foreign advertisers view the Slovenian market as attractive.

Quality of Journalism

A free press has come at a price to Slovenian journalism. Prior to the nation gaining sovereignty, many newspapers and other media were subsidized heavily by the government and by political parties. But capitalism has established the standard that media outlets become financially viable or fail. This move to privatization has created problems the government and the media professionals had not anticipated.

Government ownership ended in 1991 and, following the media laws that were established in 1994, in most cases the media professionals became stockholders in their own companies. This policy eventually created a conflict of interest in journalistic ethics. At the same time, the quality of journalism began to suffer without subsidies because very few publications could survive and compete with the existing government owned media and the already well-established publications such as Delo .

Some observers believe the decline in the quality of Slovenian media began before the nation gained sovereignty, and declined further when the press lost government subsidies. Print media was instrumental in the country's first free elections in 1990, and some newspapers suffered government scorn following the elections, depending upon which political ideology and party it endorsed. The media was so accustomed to close relationships with the established government it began censoring itself. Today the press is legally free from government control, but the Slovenian government owns stock in several large newspapers, creating an environment in which publishers are potentially fearful of provoking its stockholders in government. The arrangement has a chilling effect on the media's coverage of its parliament.

Following the country's success in gaining independence, the mood of the country was generally Xenophobic—fearful of strangers and foreigners. Following the country's short battle for independence, masses of legal and illegal immigrants as well as refugees from nearby Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina were deported. Even those non-Slovenians who had lived in Slovenia their entire lives were suddenly and unexpectedly deported. In an environment where nationalism is so pervasive, criticizing the government often creates backlash from readers and advertisers, deepening the chilling effects that prevent scrutinizing the country's leadership.

In general relations with foreign press correspondents are poor, but relations with the press in the former Yugoslavian states are especially poor. Slovenian news tends to center around Slovenian issues, and these are presented predominately with nationalist and ethnocentric perspectives. This environment stands in sharp contrast to the 1980s, when alternative and student presses launched the revolution that led to independence.

Journalism training is both fragmented and inadequate at most Slovenian colleges and universities. Journalist trade unions are also weak and unorganized. The Union of Slovenian Journalists, the Coordinating Center for Independent Media, the Slovenian Open Society Institute, and the International Federation of Journalist Balkan Coordinating Centre for Independent Media, however, have made strides in improving unions and education.

Historical Traditions

Slovenia's press dates back to the Reformation era of the fifteenth century. Following a number of Reformation papers and German newspapers, the first Slovenian paper, the Lublanske novice (The Ljubljana News), was published from 1797 to 1900. The reign of the Lublanske novice is considered Slovenia's period of enlightenment, which was shaped in part by the paper's founder, Lanentin Vodnik, who is today considered one of the most influential newsmen in the country's history. The period's second most influential newspaper, published from 1843 to 1902, the Kmetijske in rokodelske novice (The Farmer's and Craftsman's News), was founded by Janez Bleiweis. The paper was the catalyst for other publishers to distribute newspapers during the 60-year period. Of the 292 newspapers published during the Second World War, 48 of these were launched during this earlier period. Furthermore, the newspapers published between the Second World War and the 1980s were instrumental in laying the groundwork and setting the tone for a country which would break free from communist leadership and establish a democratic parliament.

Slovenia has a handful of major daily newspapers and two major weekly political magazines Mag and Mladina , all of which are published in the Slovene language. The largest of the Slovene dailies is Delo , which claims a readership of about half of all print newspapers distributed. The second largest is the Slovenske novice , originally published as a supplement to Delo . Another major daily, Dnevnik , is independently owned. Vecer is the fourth largest daily in Slovenia. All the current major news dailies were the largest papers before the country gained independence, and held their market shares in the post-communist society.

The major papers have enjoyed little competition from upstart papers. In 1997 two dailies were launched— Slovenec and Republika —but both quickly collapsed. This led critics to point to the necessity of increased government subsidy of newspapers in order to offer citizens a more diverse media landscape.

Delo is the largest Slovene daily, with 150 reporters and 10 foreign correspondents. It is also one of the oldest newspapers in Slovenia, existing for more than 50 years. It covers Slovenian affairs in what it calls a "nonpartisan manner," although observers maintain it has not strayed far from its communist beginnings. The paper is typical because it's employees are the primary shareholders,

Foreign publications and broadcasts are there for the recognized minorities in Slovenia. Hungarians and Italians operate broadcasting stations that are financially supported by the state. The Roma minority has two programs on local broadcast stations. The migrants from the former Yugoslav republics, however, have only small bulletins which are produced and distributed in individual communities.

Press Laws

The Slovenian Constitution provides for a free and open press. The law drafted in 1994 protects media independence, but allows lawsuits from those who perceive harmed from the media similar to the United States' libel laws. The law also offers journalists some protection when they have been accused of slander or libel. The new laws also address copyright, protection of personal data, and the degree to which government may be a stakeholder in the media. Journalists do not, however, have the expressed right to protect their sources, and journalists have been sued to convince them to reveal their sources.

The International Press Institute noted the law narrows the scope of individual journalists. The political elite and the communists generally still carry a great deal of influence over the media. Coverage of political agendas and events outside of the established governmental powers is largely left to the tiny segment of alternative media, which continue to struggle among the major publishing powerhouses.

Antitrust laws provide for pluralism of the media while other laws limit government ownership of shares, ownership of foreign capital, and connections between printed and broadcast media. Tax laws provide for lower rates for media entities. The government also subsidizes printing costs for newspapers and magazines.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

Foreign interests in Slovenian media have been somewhat limited. POP TV is financed by the Central European Media Enterprise, an international investor which is active in Estonia, Romania and Hungary. Channel A is owned by the Scandinavian Broadcasting Systems. Beyond these two examples, Slovenian public and commercial media is based and financed in Slovenia.

News Agencies

The Slovenian national press agency, Slovenska Tiskovna Agencija (STA) was started in 1991. There are also several smaller press agencies.

Broadcast Media

After Slovenia gained independence, the number of electronic and broadcast media establishments tripled. National channels are Radio Television Slovenia stations and Radio Television Koper-Capodistria, for the Italian minority. Slovenia's first national television channel began transmission in 1958. After 1986 national television developed programming with more national identity and more clearly became a reflection of Slovenian culture.

More than half the country has access to three commercial stations, TV3, POP TV, and Kanal A. POP TV and Kanal A are both owned by Super Plus Inc. but each channel has independent programming. Kanal A was Slovenia's first commercial television station and began broadcasting in 1989, immediately after Slovenia gained sovereignty. The other commercial stations obtained licenses in 1993. Kanal A was bought by Super Plus Inc. in October 2000. When POP TV began broadcasting in 1998, its presence was felt immediately, and it quickly became the nation's most popular station, knocking First Television Slovenia out of its prime position. POP TV garnered more than 60 percent of viewers between ages 10 and 75, while the First Television Slovenia Channel had 42 percent in 2001. Kanal A attracts 27 percent and Second Television Slovenia Channel had 15 percent. The evolution of cable in Slovenia led to the formation of local television stations. Currently, about 100 cable operators manage the country's cable television broadcasts.

Slovenia has 89 non-stop radio stations; 38 of these are commercial; 26 are local, regional and noncommercial; 15 are for Slovenes abroad; 2 are student stations; and 8 are public radio services. Radio Slovenia was founded in 1928. According to the government of Slovenia, in 2001 Slovenians listened to the radio an average of more than three hours daily. The most-listened to station is Val 202. Second is Radio Slovenia, which boasts more than 500,000 listeners.

Summary

The Slovenian media has, by law, the right to journalistic freedom. In practice however the habits and fears which accumulated over the 40 years prior to 1991 will fade at a slow pace. The Slovenian press could flourish and become one of the freest and most diverse in the world with further improvements to the media unions, communications education, and communications law.

Bibliography

"Media Policy: What is That?" AIM Press, 28 Dec. 1999. Available from www.aimpress.org .

Mekina, Igor. "Traps of a Small Market" AIM Press. 2001. Available from www.aimpress.org .

Moenik, Rastko and Brankica Petkovic. "Country Reports on Media," Education and Media in Southeast Europe. 9 May 2000.

Slovene Government Web site. Available from www.sigov.si .

The State Department, U.S. Bureau of Democracy. "Country Reports on Human Rights Practices," 25 Feb.2000.

Carol Marshall