Togo

| B ASIC D ATA | |

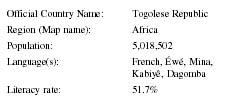

| Official Country Name: | Togolese Republic |

| Region (Map name): | Africa |

| Population: | 5,018,502 |

| Language(s): | French, Éwé,Mina,Kabiyê,Dagomba |

| Literacy rate: | 51.7% |

Background & General Characteristics

Socio-political Background

Several brief socio-political discussions, including ethnography, geography, and literacy are necessary for an appreciation of the press in Togo. Togo was placed under French administration first as a League of Nations "mandate" then as a United Nations "trust" territory at the end of World War I (WWI). Up to and through WWI, the country now known as Togo and a sizeable eastern segment of what is Ghana were one entity under German colonial rule. In the transition from a German colony to a French "trust" territory, a significant western portion of German Togoland was ceded to Britain's colonial administration of Ghana. In the process, a major speech community, the Éwé, found themselves partitioned in roughly equal numbers into two different political entities, Ghana and Togo.

Ethnography & Geography

To the east of Togo is Benin (previously Dahomey), to the north is Burkina Faso (previously Upper Volta). These two countries are significant because the Éwé speech community extends into coastal Benin in the form of Mina and Fon. Éwé, starting in Ghana and ending as Fon in Benin, belongs to the Kwa language family in the larger Niger-Congo family of languages which incorporates most of sub-Saharan Africa. The Éwé occupy roughly the southern third of the country. To their north are the Tem. To the northeast of the Tem are the Kabiyê. Moré speaking people who have strong linguistic affinity with the majority population of Burkina Faso inhabits the remaining northern tier of the country.

The Tem and the groups north of them all the way to Burkina are very predominantly Muslim. The Kabiyê and the Éwé for the most part observe their traditional religions. A significant educated elite segment in both ethnic groups is Christian, mostly Catholic among the Éwé and mostly Protestant among the Kabiyê. In Togo these ethno-religious boundaries are hard.

Literacy and Education

The population of Togo is estimated to be slightly more than 5 million. According to UNESCO's 1999 Statistical Yearbook, illiteracy among those aged 15 and over is approximately 43 percent. Approximately 76.5 percent of the population over 25 years of age have had no schooling. In 1997, 859,574 students were enrolled in primary schools. Some 178,254 students were enrolled in secondary schools. In 1996, 11,462 students were enrolled at Université du Benin in Lomé, the capital of Togo. These statistics present an accurate impression of the rate of literacy and the very steep educational pyramid. The significance of this impression is enhanced when the fact that all formal schooling or education at all levels is presented strictly in French, the language of colonial legacy and the official language. Not surprisingly the reading public reads largely in French.

Language Policy

The government, in power since 1969, in the late 1970s and early 1980s adopted two African languages. They are indigenous to Togo, as national languages, Éwé and Kabiyê. In 1977, the government established a pedagogical research institute, Direction de la Formation Permanente de l'Action et de la Recherche Pedagogique (DIFOP) to produce Éwé and Kabiyê textbooks and generally oversee the training and preparation of teachers for these two languages. DIFOP was located on the campus of the University of Benin in Lomé. The ultimate intention was to replace French with the designated two Togolese languages. The one daily newspaper, Togo Press , in French (at the time called La Nouvelle Marche ), includes a page in Éwé and another in Kabiyê. Radio and television broadcasts are the only other major outlets for these and other national languages indigenous to Togo. In the meantime French remains the official language and permeates every formal aspect of Togolese life.

The Press

As mentioned above, there is one daily newspaper, the Togo Press . The paper is mostly in French with segments in Éwé and Kabiyê. According to Africa South of the Sahara 2001 , the circulation of Togo-Press is 8,000. The same source lists a number of other periodicals and their circulation numbers where special political or linguistic interests constitute their respective audiences.

- L'Aurore (Lomé, Weekly, Circulation 2,500)

- La Conscience (Lomé, Circulation 3,000)

- Crocodile (Lomé, Twice weekly, Circulation 5,000)

- La Dépêche (Lomé, Bimonthly, Circulation 3,000)

- L'Eveil du Travailleur Togolais (Lomé, Quarterly, Circulation 5,000)

- Game su/Teu Fema (Lomé, Monthly, in Éwé and Kabiyê, Circulation 3,000)

- Politicos (Lomé, Twice monthly, Circulation 2,000)

- Le Regard (Lomé, Weekly, Circulation 3,000)

- Tingo Tingo (Lomé, Weekly, Circulation 3,500)

- Togo-Images (Lomé, Monthly, Circulation 5,000)

The numbers given the periodicals addressed to special audiences would suggest a total readership in substantial numbers within the literate educated population. The government's efforts towards the promotion of Éwé and Kabiyê at least through the press are reflected accurately. The vast majority of the literate population is literate in French. Nevertheless a small but a critical mass of citizens has become literate in the national languages. The latter, however, are not sufficient in number to disturb the overwhelming balance of power in favor of the former. More importantly, an overwhelming inclination for French remains intact among the governing elite whatever their political and ideological perspectives might be.

State-Press Relations

The newspapers and periodicals listed may not all be available at all times. The number and identity of the periodicals are subject to change from year to year under political and financial stresses. Editors and editorial boards may change. This instability reflects the political and social stresses and strains within which both the press and the body politic at large exist and interact. The socio-political status of Togo has not evolved to a point where one could consider the "government," the "press," the "economic sector," the "judiciary," the "military," and so on as distinct entities. The individual participants in these various sectors for the most part belong to a small French educated elite. There is a great deal of mobility of participants from one sector to the other. A qualification somewhat peculiar to Togo needs to be made here. The President, General Gnasimbe Eyadema, is ethnically a Kabiyé and is a Protestant. He is rightly claimed to have close connections with German economic-agrarian and food distribution interests on the one hand and on the other, British interests with reference to the one oil refinery in the country. He has been president since 1969 with strong support from his own ethnic group, which tends to predominate in the military and bureaucracy.

It is not surprising that there is only the Togo Press ; it is heavily government controlled. The issue of "censorship" does not really arise directly, however, the influence does exist. A Press and Communication Code passed through the National Assembly in January 1998. "Articles 90 to 98 make defamation of state institutions or any member of certain classes of persons, including government officials, a crime punishable by imprisonment for up to 3 months and fines of up to $4,000 (2 million CFA francs)." Article 89 applies a similar provision to protect the president (U.S. Department of State).

Attitude toward Foreign Media

In addition to the publications within Togo, Lomé and several other major towns in the country provide ample access to French publications such as Le Monde , Jeune Afrique , and Le Nouvel Observateur . These are of special interest to the expatriate communities as well as the university educated Togolese segment of society. Several major countries have cultural centers in Lomé. Their libraries make available promotionally oriented publications in their respective languages. Newsweek , Time , and The Herald Tribune are available through the American Cultural center as well as bookstores and hotel newsstands. There are also a number of English language publications available from neighboring Ghana and Nigeria.

The governing elite does not seem to have a policy on foreign publications. One major reason is that only the educated elite who can afford these publications would read them. Another reason is that for the most part the expatriate community reads them, and they insist on having them available. A third reason, and likely the most important one, is that criticism within the foreign media is rarely initiated internally. The Ghanaian and Nigerian papers and journals are quite free in comparison, and frequently provide unfavorable information. These are promptly "corrected" by the daily Togo Press and its periodic sup plements.

Broadcast Media

Observers would have to turn to radio broadcasts and television transmissions to find some diversity and some recognition of indigenous languages other than Éwé and Kabiyê. Radio and television in sub-Saharan Africa, as elsewhere, form a continuum with print press especially where indigenous African languages are concerned. They provide a window on the relative influence of external and internal forces as well as the relative influence within internal power blocs.

Radio Kanal FM broadcasts in French and Mina (a socio-political dialect of Éwé spoken in the southeastern segment of the country centered around the city of Aneho. Radiodiffusion du Togo (National) broadcasts from Kara, the capital of the Kabiyê region to the northeast of the Éwé, and broadcasts in French, Kabiyê, and other languages indigenous to Togo. Télévision Togolaise transmits programs in French and languages indigenous to Togo. The latter is true especially where the news is concerned.

Within the country, according to the CIA, there were 940,000 radios and 73,000 televisions in the late 1990s.

Bibliography

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). The World Fact-book—Togo . Available from http://www.cia.gov/cia/ publications/factbook/geos/to.html .

Cornevin, Robert. Hiostoire du Togo . Paris: Berger-Levrault, 1969.

Decalo, Samuel. Historical Dictionary of Togo . 2nd ed. Metuchen, NJ: The Scarecrow Press, 1987.

Der-Houssikian, Haig. "Togo's Choice" In The Linguistic Connection , Ed. Jean Casagrande, 73-82. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, Inc. 1983.

Europa Publications 2000. Africa South of the Sahara 2001, 30th Edition . London: Europa Publications, Taylor and Francis Group, 2001.

Francois, Yvonne. Le Togo . Paris: Karthala, 1993.

UNESCO. African Community Languages and their Use in Literacy and Education . Dakar, 1985.

UNESCO. Statistical Yearbook . Lanham, MD: Berman Press, 1999.

U.S. Department of State. "1999 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices." Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor/U.S. Department of State: February 25, 2000. Available from www.state.gov/www/ global/human_rights/1999_hrp_report/togo.html .

Haig Der-Houssikian

any other thing i will talk later

thanks