Tunisia

Basic Data

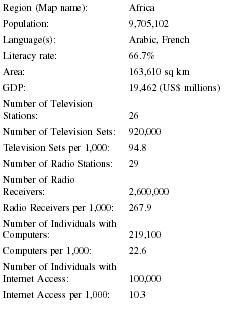

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Tunisia |

| Region (Map name): | Africa |

| Population: | 9,705,102 |

| Language(s): | Arabic, French |

| Literacy rate: | 66.7% |

| Area: | 163,610 sq km |

| GDP: | 19,462 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Television Stations: | 26 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 920,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 94.8 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 29 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 2,600,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 267.9 |

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 219,100 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 22.6 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 100,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 10.3 |

Background & General Characteristics

Like Algeria and Morocco, Tunisia inherited the structure and characteristics of its press from the French. A protectorate within the former French colonial empire of North Africa between 1881 and 1956, Tunisia absorbed much of the cultural and intellectual traditions imposed upon it over the span of three generations. The colonial Tunisian press began in 1889 with the founding of Le Petit Tunisien and followed the traditional French model: all newspapers were highly editorialized and represented the official position of the government. Independent views were discouraged and nationalistic sentiments muzzled, and in 1933 French officials closed down all newspapers and periodicals suspected of disseminating autonomist views. All that remained were newspapers destined for the colonial residents and the Tunisian cultural elite. When it gained its independence in 1956, Tunisia retained almost the same press structure. For the next 20 years, it made the transition from colony to autonomous statehood under the authoritarian leadership of President Bourguiba, once a journalist with the suppressed nationalist daily La Voix du Tunisien .

In 2002 there were seven major daily newspapers in Tunisia, all of them published in Tunis, the capital, and owned either directly by the state as a public corporation ( L'Action , Al Amal , and La Presse ) or privately owned but openly pro-government. It is worth noting that Arabic-language dailies have often represented a reforming, nationalistic trend against French language and culture in the former French colonies of North Africa. Nevertheless, most of the Arabic-language dailies published in Tunis ( El Horria, Essahafa, Assabah ) are the translated versions of French-language newspapers ( Le Renouveau , La Presse , and Le Temps ) and are owned by them. Ironically, the most widely read daily is now the Arabic-language Ach Chourouk , with a circulation of 110,000. The lack of even one major opposition newspaper has been a recurring argument for those who maintain that freedom of the press has not yet become a reality in Tunisia.

In terms of circulation, the most important Tunisian newspapers are:

- Al Chourouk , in Arabic, circulation 110,000

- L'Action (1932), in French, circulation 50,000

- Al Amal (1934), in Arabic, circulation 50,000

- Assabah (1951), in Arabic, circulation 50,000

- La Presse (1936), in French, circulation 40,000

- Le Temps (1975), in French, circulation 42,000

- Le Renouveau , in French, circulation 23,000

L'Action and its Arabic edition Al Amal are the official newspapers of the largest, pro-government political party in Tunisia, the Rassemblement Constitutionnel Démocratique (RCD). It is the new name for the old Parti Socialiste Destourien (PSD), which holds 148 seats in the house of representatives, the Tunisian Chambre des Députés, against 34 seats belonging to a moderate opposition.

For a population of 9,705,102 (2002), a GDP of 62.6 billion (2000), and a literacy rate of 67 percent, Tunisia has an aggregate daily newspaper circulation of 375,000 (circulation per 1,000: 26). It publishes a total of 22 daily newspapers and consumes 12,500 metric tons of news-print every year. It also publishes over 210 national periodicals (weekly and monthly), with an aggregate circulation of 900,000 and oversees the distribution of more than 700 foreign magazines and newspapers throughout the country.

Economic Framework

The majority of Tunisian newspapers rely on government subsidies for their economic survival. The Tunisian government also pays for the publication of official announcements and the purchase of equipment and news-print. These subsidies are distributed to pro-government and opposition newspapers alike, and a presidential decree (April 10, 1999) stipulated the amount of yearly official subsidies allotted to the newspapers published by the opposition parties. What could be interpreted as an unusual democratic generosity represents in fact a subtle, but effective control of the opposition's newspapers, as it erodes their ability to provide alternate viewpoints or articulate any real criticism of government policies.

Press Laws

Tunisia inherited from its former French colonial occupant a political structure and a cultural environment that permits the censorship of the press for the purpose of preserving public order. The French government instituted the first press codes during its colonial protectorate in Tunisia (1881-1956) and never hesitated to muzzle the press or to shut down nationalistic publications. After Tunisia gained its independence in 1956, similar press codes remained in effect under the 21-year, single-party regime of President Habib Bourguiba. The leader of Tunisia in 2002, President Zine Ben Ali, was once its former chief of military intelligence. After assuming power in 1987 (and being re-elected in 1994 and 1999, Ben Ali took a personal interest in the country's press code. It was amended twice, in August 1988 and August 1993. Then, on the occasion of the celebration of the International Freedom of the Press Day (May 3, 2000), President Ben Ali convened a meeting with government officials, journalists and newspapers editors for the purpose of developing suggestions and guidelines to reform the press code. According to official sources, the meeting was called by the president to "improve the performance of the media in general." Ben Ali thus castigated Tunisian editors and journalists: "Every morning I find your newspapers on my desk … and I have to say that I do not find anything interesting to read any more." When his guests explained that the timidity of the Tunisian press was due to the self-imposed censorship and prior restraint required of all newspapers by the Ministry of Information, Ben Ali replied: "Write as you see fit. Be critical, as long as what you say is true. Please write, and if anyone ever bothers you, just contact me!"

The president's encouragement for truth and boldness in the press has failed to impress a number of outside observers. They routinely complain that the Tunisian press walks the party line and dares not criticize government policies or even report instances of corruption or incompetence on the part of public officials.

The latest reform of the press code was officially adopted by the Tunisian House of Representatives on April 30, 2001, by a vote of 176 yes, 6 abstentions, and no dissensions. While the new code still prescribes prison terms and fines for "sedition and the spreading of false news," it removes the crime of "slander against the public order," (article 51) which had been used in the past as a vague and standard charge against opposition journalists. It also requires editors to hire at least 50 percent of their staff from candidates holding advanced degrees in journalism and lessens the length of time a newspaper can be suspended from six to three months (article 73). Freedom of the press and freedom of speech were also re-affirmed in the recent constitutional reform adopted by a vast majority of voters in the referendum of May 26, 2002 (article 5).

Censorship

As with other countries of Northern Africa, one should maintain a sense of perspective when dealing with censorship and the freedom of the press, especially when the frame of reference is a Western point of view. According to "Reporters Without Borders," the "Committee to Protect Journalists," and the "Committee for the Defense of Liberties and Human Rights in Tunisia (CRLDH)," three watchdog organizations located outside of Tunisia, newspapers and periodicals representing the views of political and religious minorities are routinely suspended, fined, and otherwise prohibited. Journalists have also been harassed and even brutalized by plain-clothes Tunisian police. Al Tariq Al Jahid , an opposition newspaper, was seized in March of 2001, while Hamma Hammami, publisher of the Tunisian Communist Workers' Party newspaper, El Badil , was sentenced on February 3, 2002, to nine years in prison for "spreading false news, and inciting rebellion." (The sentence was later reduced on appeal to a three-year term.) Still, Tunisia is not a dictatorship where editors are threatened and journalists tortured, as is the case in several countries of the region. Actual censorship of the press is infrequent, since most journalists and editors choose to operate within the guidelines established by the Tunisian government.

News Agencies

Tunisian newspapers rely on two international press agencies: Agence France-Presse (AFP) and the Associated Press (AP). They also use the Maghreb Arabe Press (MAP), and the state-owned Tunisian press agency Tunis Afrique Presse (TAP), located in Tunis.

Broadcast & Electronic News Media

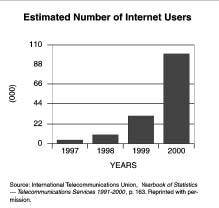

The Internet is operated by a single Internet service provider (ISP), and now reaches over 110,000 users in Tunisia. The government sponsors an official Web site, www.tunisie.com . Radio broadcasting has considerably extended its coverage since it first began to transmit in

Education & Training

The Université de Tunis offers a degree in Journalism through its Institute of Press and Information Sciences (Institut de la Presse et des Sciences de l'Information, or IPSI). Continuing education is offeredto professional journalists at the Centre Africain de Perfectionnement des Journalistes et des Communicateurs (CAPJC). The number of professional journalists in Tunisia has increased by a factor of 50 percent in the last 10 years (639 in 1990 and over 1,000 in 2002), and there were 71 foreign correspondents accredited in 2001. A journalist can work legally only if he or she holds the professional journalist card delivered by the government. The profession is controlled by two pro-government organizations: the Association des Journalistes Tunisiens and the Association Tunisienne des Directeurs de Journaux, both dominated by members of the RCD ruling political party.

Summary

Tunisia has a growing, modern and professional press. However, it lacks the diversity of opinion necessary to assert itself and make it emerge from the patronizing tutelage of the government. While it is true that Tunisian authorities stifle true freedom of the press, it must also be kept in mind that the country seeks to establish itself as a pro-Western, moderate Islamic nation. The government claims that it must impose guidelines upon the press because of the threat represented by Islamic fundamentalists and radical activists. Most outside observers are not convinced by this argument. They point out that the stifling of free speech in the defense of civil liberties is a rationalization unlikely to reach its intended goals. However, the critics of the Tunisian government also find themselves in a difficult predicament. Democracy, free speech, equality under the law, and freedom of the press are western political concepts. African nations have struggled for decades to free themselves from the constraints of their colonial past. To some, freedom of the press is an imported idea unsuitable to Islamic regimes whose political structures and traditions go back more than a thousand years.

Bibliography

Abdelmalek, Triki. "Freedom of the Press in Tunisia." Thesis. University of Missouri-Columbia, 1989.

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). World Factbook 2001 . Directorate of Intelligence, 2002. Available from www.cia.gov .

Committee to Protect Journalists . Available from www.cpj.org .

Lofti M'Timet. "A Comparative Analysis of Mass Media Systems in the Maghreb: Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco." Thesis. University of Minnesota, 1986.

The Press in Tunisia. London: Article 19 (International Centre Against Censorship), 1993.

Tunisia: Attacks on the Press and Government Critics. London: Article 19 (International Centre Against Censorship), 1991.

UNESCO Statistical Yearbook UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 1999.

Eric H. du Plessis

I AM UNDERGOING A MASTERS DEGREE IN ARTS AND MY THESIS AIMS To identify a range of interesting techniques used in Arabic advertising today, such as the language of advertising, the use and switching between Standard Arabic and Colloquial Arabic, phonological constraints due to various dialects and the use of orthography denoting standards.

I have opted for the Tunisian press and in order to carry out my study I will need periodicals/magazines from where I will take the adverts, namely a weekly publication and i will sample 1 whole year.

Here is my request: Which periodical would you suggest (arabic)

many thanks

and best regards

John Attard - malta