Ukraine

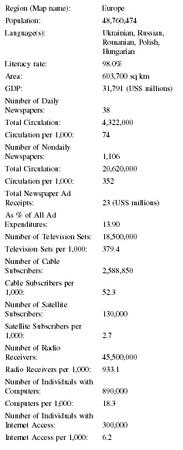

| B ASIC D ATA | |

| Official Country Name: | Ukraine |

| Region (Map name): | Europe |

| Population: | 48,760,474 |

| Language(s): | Ukrainian, Russian, Romanian, Polish,Hungarian |

| Literacy rate: | 98.0% |

| Area: | 603,700 sq km |

| GDP: | 31,791 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Daily Newspapers: | 38 |

| Total Circulation: | 4,322,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 74 |

| Number of Nondaily Newspapers: | 1,106 |

| Total Circulation: | 20,620,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 352 |

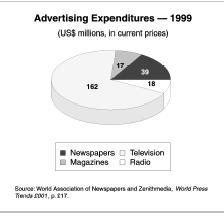

| Total Newspaper Ad Receipts: | 23 (US$ millions) |

| As % of All Ad Expenditures: | 13.90 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 18,500,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 379.4 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 2,588,850 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 52.3 |

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 130,000 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 2.7 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 45,500,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 933.1 |

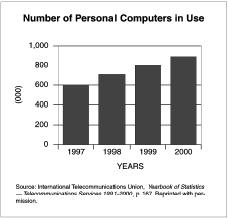

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 890,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 18.3 |

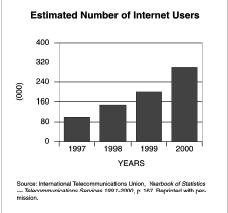

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 300,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 6.2 |

Background & General Characteristics

Publishing in Ukraine started in 1574 when the first Russian printer I. Federov printed Azbuka ( The Primer ) in the city of Lviv. The introduction of printing laid the foundation for the development of printed press. Early periodicals in the western part of the country, which was occupied by the Austro-Hungarian Empire, appeared in foreign languages. In 1776, the first newspaper, Gazette de Leopol , was published in French and in 1811, Gazeta Lwowska appeared in German and later in Polish. The periodicals in eastern Ukraine, which was part of the Russian Empire, came out in the Russian language with Kharkovsky Ezhenedelńik ( Kharkiv Weekly ) in 1812, Kharkovskie Izvestiya ( Kharkiv News ) in 1817, and the magazine Ukrainsky Vestnik ( Ukrainian Herald ) in 1816, just to name a few. The first newspaper, Zorya Halitska ( Galician Dawn ) in the Ukrainian language came out in 1848. In the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century, the further development of printed media included the emergence of new newspapers and magazines and the growth of their circulation. This process was constantly accompanied by the closure and reopening of periodicals in the Ukrainian language depending upon the political situation in Austro-Hungarian and Russian empires.

After 1917, the press became an ideological instrument of the ruling Communist Party. In pursuit of influence on the population and education of the masses in the Communist ideology, it facilitated further growth of the printed press in Ukraine. In 1925, there were 116 newspapers with a total single-issue circulation of 1.33 million copies and 369 magazines and other periodicals with an annual circulation of 14.7 million copies. In 1967, there were 2,564 newspapers, 2,100 of which were published in the Ukrainian language. The most influential newspapers were: Radyanska Ukraiina ( Soviet Ukraine ), Pravda Ukrainy ( Truth of Ukraine ), Robitnicha HazetaWorkers' Newspaper ), Silśḱi Visti ( Rural News ), Molod' Ukraiiny ( Ukrainian Youth ), Kultura I ZhittyaCulture and Life ), Literaturna Ukraiina ( Literary Ukraine ). The newspapers had a single-issue circulation of 16.9 million a year, and the 323 magazines and other periodicals had an annual circulation of 123.7 million that year.

During World War II, from 1941 to 1944, an underground press was organized by the resistance forces in the territories occupied by the Nazi Germany. Radio broadcasting was banned by fascists. As the fascists advanced further into the country, many printing and radio broadcasting facilities had to be evacuated to inside the Soviet Union where publishing houses and radio stations continued their work.

Before Ukraine proclaimed its sovereignty in 1991, the Soviet journalists and editors were guided by the principles and instructions of the Communist Party to emphasize the optimistic and the positive and to place prominently reports about economic achievements (which were not necessarily true) and stories about the heroes of Socialist labor and promising initiatives. Anything negative, tragic, or controversial happening in the country or anything positive taking place in the capitalist countries was seldom allowed to be covered by reporters and journalists.

The monopoly on information in Ukraine, like in all other former Soviet republics, was executed through banning underground opposition publications, jamming foreign radio stations, and applying legal actions against those who listened to foreign radio. It also included the restrictions on the distribution of foreign press, especially from Western countries, to a limited number of libraries and officials, and even banning Soviet tourists from bring foreign publications into the country.

In the last decade of the twentieth century and in the first years of the twenty-first century, the Ukrainian mass media have undergone a drastic transition from the Soviet-style to the democratic and free-market mode of work. Controlled for most of the twentieth century by the conservative Communist system, media have learned to operate in a new democratic, economic, political, ideological, and cultural environment. Learning to work in a new sovereign state with diametrically opposite politico-ideological and socioeconomic environment required tremendous efforts on the part of many professionals involved in media business in reevaluating the legacy of the Communist past, rethinking the old principles of journalism, and adjusting to the novel concepts of the freedom of press and pluralism of opinion.

The legacy of the Soviet past, the realities of the new nation-state, and linguistic pluralism make the cultural identity of many Ukrainian media a rather complex and multidimensional phenomenon.

The new challenges of the post-Soviet Ukraine have had a great impact upon the quality of journalism. Most of the news, commentaries, articles, television, and radio programs involve their readers and listeners in serious deliberations on democratic, social, economic, political, ideological, educational, and cultural reforms and changes in the country. Media plunged into hot debates and controversies about constructing a new nation-state and in searches for its national Ukrainian identity. Some old-guard journalists stuck to past beliefs and values and continued to glorify the Soviet legacy, whereas others struggled with their Communist stereotypes, clichés, and work ethics. Most of the new generation of journalists have accepted the democratic principles of journalism and are learning how to be unbiased in their evaluations, to present pluralism of opinions, to avoid asymmetrical selectivity of facts, and to withstand prejudice and onesidedness in covering sociopolitical events in a rapidly changing society. The process has not been an easy one. Controversy exists about the excessively judgmental nature of the work of many journalists and reporters. Many mass media are accused of overloading their pages with sensational and negative information to attract readers.

In 2002, according to V. Chizh, Chair of the State Committee of Ukraine on Information Policy, TV, and Radio Broadcasting, over 15,000 printed and electronic publications were officially registered in the country, with 5,696 newspapers and magazines among them. However, it is difficult to estimate how many of these publications are still brought out because some of them have never been even produced, or were issued for a short period of time and do not exist any longer.

As democratic Ukraine opens itself to the world, the people receive greater access to international printed publications, some of which are issued in a translated version for larger audiences who do not speak foreign languages. The national printed press is published in Russian, English, German, and many other languages including the languages of indigenous domestic minorities. Due to a considerable number of mixed marriages, many Ukrainians are bilingual, generally speaking Ukrainian and Russian. Because most (62 percent) Russians and Russian-speaking people live in the eastern and southern areas, mass media in these parts of the country predominantly use Russian language, and the Ukrainian language is more often used in central and western Ukrainian media. In 2002, during the parliamentary elections to the country's highest legislative body, Verkhovna Rada, 84 percent of the population in Kharkiv, the second largest city of Ukraine, responded positively to the question included in their ballots whether they would agree that Russian language should be given the same status as the Ukrainian language. Nevertheless, some nationalists, especially in Lviv region, strongly objected to the use of the Russian language in media.

In the 1990s, the democratic developments of the country were accompanied by the fast increase in the number of publications and by the decrease in their circulation. In 1997 newspaper subscriptions dropped to 2.6 million copies and magazines subscriptions to 910,000. These negative occurrences happened because of the rising cost of publishing, printing, and delivery as well as a significant reduction of state subsidies and purchasing possibilities of population. The socioeconomic stratification of the capitalist Ukrainian society based on the wealth led to the emergence of two types of media: one for the small elite and a thin layer of middle class, and a second for low and impoverished masses.

In a country that inherited a very well-educated population from the Soviet era (98 percent literacy rate), the interest in printed and broadcast word among peoples of all ages remains very high. Although in the Soviet Ukraine many blindly believed what the media said, in the times of pluralism people struggle with the idea that they must give meaning to what they read, watch, and hear, rather than dismissing it as propaganda.

The larger part of the printed media (72.4 percent) consists of daily newspapers. The majority of the printed and electronic mass media takes place in the capital city of Kyiv. However, 64 percent of printed media circulation occurs at the local level in twenty-six regions.

The newspapers with the most subscriptions in 2002 were: Silśḱi in Ukrainian (560,340), Golos Ukraiiny ( Voice of Ukraine ) in Ukrainian and Russian (114,904), Uryadovyi Kuríer ( Government Carrier ) in Ukrainian (101,904), Komunist ( Communist ) in Ukrainian and Russian (92,739), Ukraiina Moloda ( Young Ukraine ) in Ukrainian (84,485), Robitnicha Gazeta ( Workers' Newspaper ) in Ukrainian (71,283), Prattsya I Zarplata ( Work and Salary ) in Ukrainian (49,899), Tovarisch ( Comrade ) in Ukrainian and Russian (29,821), Rukh ( Movement ) in Ukrainian (25,855), Osvita Ukraiiny ( Ukraine's Education ) in Ukrainian (20,455), Ukraiiksḱi Futbol ( Ukraine's Soccer ) in Ukrainian (17,203), and Molod' Ukraiiny ( Youth of Ukraine ) in Ukrainian (11,405). Since many people buy newspapers retail, the real number of circulation may be much higher for some publications. For example, during a seven-year period, Uryadovyi Kuríer claimed to have had an annual circulation between 130,000 and 230,000 and Golos Ukraiiny had 170,000 versus 101,904 and 114,904.

The most influential national newspapers are: Uryadovyi Kuríer ( Government Carrier ), Kyiv Post , 6 Kontinentov ( 6 Continents ), AVISO , Argumenty I Fakty v Ukraine ( Arguments and Facts in Ukraine ), BiznesBusiness ), Vseukrainskie Vedomosti ( All-Ukrainian Official Reports ), Golos Ukraiiny ( Voice of UkraineDen' ( Day ), DK-Zvyazok ( DK-CommunicationPravda Ukraiiny ( Ukraine's Truth ), Osvita UkraiinyUkraine's Education ), Robitnicha Gazeta ( Workers' Gazette ), Silśsḱi Visti ( Rural News ), Slovo Batḱivschiny ( Word of Fatherland ), Stolichnye Novosti ( Capital NewsUkraiina Moloda ( Young Ukraine ), Ukraiinsḱe Slovo ( Ukrainian Word ), Ukraiinsḱi Futbol ( Ukrainian Soccer ), and Dzerkalo Nedili ( Weekly Mirror ).

Among the most influential regional and local press are Podilśka Zorya ( Podilśk Dawn ) in Vinnitsi; Kochegarka ( Furnace-Feeder ) in Gorlivki; V Novyi VekInto New Century ) in Dniprodzerzhinsḱ; Prospekt Pravdy ( Pravda Avenue ) and Litsa ( Faces ) in Dnipropetrovsḱ; Gorod-NN ( City NN ) and Donbass in Donetsk; Zaporizḱa Pravda , Panorama in Zaporizhzhya; Vilńyi Golos ( Free Voice ) in Kolomyya; Programa ta Novyny ( Program and News ) in Kremenchug; Vysokyi Zamok ( High Castle ) in Lviv; Azovskie Novosti ( Azov News ) in Mariupol'; Nikolaevskie Novosti ( Mykolaev News ) in Mykolaev; Glasnost' and Odesskie Delovye Novosti ( Odesa Business News ) in Odesa; Absolyutno Vse ( Absolutely Everything ) in Sevastopol'; Kharkovsky Kuríer ( Kharkiv Carrier ) in Kharkiv; and Bukovyna in Chernivtsi.

The following case gives an approximate picture of the situation of local mass media in the economically developed Luhansk region, one of the largest among 26 regions in the country with a population of approximately 3 million people. In 2002, there were 283 newspapers and 13 magazines in the region, 26 of them in the Ukrainian language, 55 in the Russian language, and 216 in both languages. Forty-three publications had general political and social information orientation, 15 were affiliated with parties, 36 were established by the industrial enterprises and organizations and reflect their life, and 31 were sponsored by the state bodies. Twenty-three publications addressed entertainment, tourist, and leisure issues. Eleven publications focused on religion, 38 on advertisement, 15 were issued for children and youth, and 29 had general information. Thirty-seven TV and radio companies with various types of ownership functioned in the region.

For over 70 years in the twentieth century, the atheistic country excluded religious perspectives from the state mass media and severely restricted the rights of religious organizations to freedom of press. The renaissance of religious printed press as well as the access of clergy to some state television and radio channels became a prominent feature of the post-Soviet Ukraine at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Both state and independent television and radio regularly broadcast services from churches, mainly from the dominant Ukrainian Orthodox Church, during the major religious holidays. In 2000, over 150 printed religious publications, excluding an unidentified number of small publications (generally parish newspapers), were issued in the country. The Moscow and Kyivan Patriarchates of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church have the largest number of publications: Pravoslavnaya Gazeta ( Orthodox Gazette ), Pravoslavna Volyn' ( Orthodox Volyn ), Pravoslavna Tavriya ( Orthodox Tavriya ), Kharkovskie Eparkhialńye Novosti ( Kharkiv Eparchial News ), and Informatsiinyi Buleten' ( Information Bulletin ). Dlya Tebya ( For You ) of Baptist denomination, Arka ( Arch ) of the Greek-Unitarian Church, Shabat Shalom , Sholem , and Khadashot Novosti ( Khada-shot News ) of Jewish faith, Nova Zirka ( New Star ), and Zhiva Voda ( Living Water ) of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, Islamic Al-Bayan , Arraid , and other newspapers are freely published in the country. Despite the religious pluralism in the post-Soviet Ukraine, the equal representation of all denominations in media, especially on television, remains an issue of debate.

Ukraine produces a significant number of magazines addressing social, political, scientific, entertainment, and informational technology issues. A number of them are published in various domestic and foreign languages. Most of them are issued in Kyiv: Motor News , Office , Sobstvennik ( Owner ), Internet UA , Aviatsiya I Vremya ( Aviation and Time ), Bankivsḱa Sprava ( Bank Information ), Viisáo Ukraiiny ( Ukrainian Army ), Vokrug Sveta ( Around the World ), Delovaya Zhizn' ( Business Life ), Zovnishnya Torgovlya ( Foreign Trade ), Lyudyna I Politika ( People and Politics ), Naturalist , Polityka I Kuĺ tura ( Politics and Culture ), Svit Nauki ( Light of Science ), and Ukraiina ( Ukraine ). There is a substantial growth of magazines devoted to computer technologies and entertainment. Although the country boasts a great variety of magazines, circulation is generally low, except for those on entertainment and sports. The scientific journals published by academic and research institutions reduced their circulation drastically due to the economic constraints.

Many universities have their own printed newspapers with an electronic version. Some have large circulations, including Kolega ( Colleague ) in Kyivo-Mogilyansḱa Academy, Inzhinernyi Rabochii ( Engineering Worker ) in Zaporizhzhya State Technical University, Politekhnik ( Polytechnician ) in Kharkiv State Polytechnic University, Donetskii Politekhnik ( Donetsk Politechnician ) in Donetsk State Technical University, and Zapoizḱyi Universitet ( Zaporizḱyi University ) in Zaporizḱyi State University.

Whereas the Soviet Ukraine issued most of its newspapers on an almost daily basis in 4 pages, in the sovereign country the majority of the newspapers increased the number of pages up to 8 or even 24, but they reduced their appearance to three to five times a week. Once absent, the commercial and classified ads and letters from the readers expressing different opinions have found their way onto the pages of many media.

Economic Framework

The media business in Ukraine operates in an economy that is not recognized by the major world industrial countries as a market leader. Its transitional status from state-planned to supply-and-demand market has a great impact on the orientation, nature, and quality of the work of correspondents, journalists, reporters, and the content of the media. The major watershed for media business in this period lies between the powerful groups, which unofficially in Ukraine are called clans of oligarchs or magnates, and the political parties, some of which are often very closely associated with the big capital. An oligarchy consists of very rich individuals who have a monopoly in certain areas of the market and send their representatives to Verkhovna Rada and to the executive bodies of power. Oligarchs may depend upon those in the state structures that appointed them to their positions and who can dismiss, charge, or eliminate them. The oligarchic blend of party, business, and state is sometimes called the party of power.

Oligarchs do not control the printed press for profit reasons but rather for promoting their political ambitions and businesses as well as their parties' and clans' agendas and for creating a positive image. Often uninterested in learning how to do profitable media business, oligarchs' main revenues come from other businesses, frequently illegal, rather than from selling newspapers, magazines, television and radio programs, or informational services. Journalists find themselves under strict pressure from the oligarchs, which is often covert and is manifested in the form of friendly advice to avoid problems. The covert and overt pressure has a negative impact on the professionalism of journalists and the quality of their work. The picture is somewhat better with private television companies, which strive to gain profit from producing innovative shows, serial films, and entertaining programs. Television companies place more commercial advertising than the printed press. Nonetheless, it is recognized by experts on journalism that Ukraine's television and radio stations are not exempt from the influence of the oligarchs.

One of the powerful clans, Donchane controls mass media in the coal mining Donetsk region as well as the publishing house Segodnya (Today) in Kyiv. Dnipropertovsḱa semýa (Dnipropetrovsḱ family) consists of several small clans in an industrial region, Dnipropetrovsk, which was known during the Soviet times as the homeland of the Communist Party leaders L. Brezhnev and V. Scherbitski and now as the bulwark of the acting President L. Kuchma. V. Pinchuk group owns the biggest cellular phone network, KyivStar GSM, a popular newspaper Fakty ( Facts ), a local TV channel, and the national channel ICTV. The Dnipropetrovsḱ media has had a pro-presidential orientation and in 2002, during the parliamentary elections it supported the Za Edynu Ukraiinu! (For Unified Ukraine!) block, a party in power. The son-in-law of President Kuchma, Pinchuk is a member of Verkhovna Rada and the owner of local metallurgic plants is the region.

A. Derkach's group owns the holding Ukrainian Press-Group that publishes Ukrainian versions of the popular Russian newspapers Komsomolḱaya Pravda ( Komsomol Truth ), Moskovskii Komsomolets ( Moscow Komsomol Member ), Argumenty I Fakty ( Arguments and Facts ), and Telenedilya ( TV Weekly ). Since the group purchased the copyrights for their publishing in Ukraine, the influence of Russian media owners on the content of their publications significantly diminished. The group also co-owns Stolichnye Novosti ( Capital's News ) and the Web site MIGnews along with A. Rabinovich, the

The Lviv family controls the media in the western part of the country, and is known for its active participation in the nationalistic movement at the beginning of the 1990s. In 1997, a new governor, M. Gladii, founded a newspaper, Ukraiinski Shlyakh ( Ukrainian Road ) to which every state employee had to subscribe. The newspaper became a mouthpiece of the Agrarian Party of Ukraine. It also has close connections with the Social Democratic Party headed by V. Medvedchuk, an influential businessmen in the Lviv region who, along with V. Surkis, controls the television channel Inter and the newspapers Kyivski Vedomosti ( Kyiv Official Reports ) and Biznes ( Business ). In 2002, Medvedchuk became the Head of the Presidential Staff Office.

Kharkiv Magnates Group operates in the city of Kharkiv. Although less influential than Donchane and Dnipropetrovsḱa semýa, the group owns several media in the eastern part of the country. S. Davtyanś owns the television channel, Simon, which according to the ratings yields among the Kharkiv region inhabitants only to popular national Inter and 1+1 TV channels. He also publishes a weekly Obýektivno ( Objectively ). His rivalry in hotel and groceries business, NPK Company, possesses the TK TONIS-Tsentr (TONIS Center) and Vechernii Kharkov ( Evening Kharkiv ) newspaper.

One niche in the media market is filled with the national and regional media owned by the state governing bodies. They are very often co-owned with the employees of the companies. For example, Uryadovyi Kuríer ( Government Carrier ) belongs to the national bodies of the executive branch of the power structure. It publishes complete texts of laws, decrees, and directives of the President, the Cabinet of Ministers, commentaries and clarifications of experts on legal, scientific, and other issues. Another newspaper, Robitnicha Gazeta , published in Russian, is a cross-ownership of the Cabinet of Ministers and the staff of the newspaper. Kyivsḱa Pravda is sponsored by Kyiv Region Rada and the newspaper staff.

Daily Vecherni Visti ( Evening News ), financed by the Company OOO "BB," is controlled by the former Prime Minister Timoshenko and the leader of the Verkhovna Rada fraction Batḱivschina (Fatherland), Turchinov.

Many newspapers have strong party affiliation (the fusion of parties with oligarchs should be also kept in mind). It is estimated that in 2002, approximately 75 percent of all national printed media belonged to political parties and political organizations, which provided them with major financial support. The Communist Party of Ukraine, founded in 1993 as a remnant of the former Communist Party of the Soviet Union, inherited a well-developed network of media production and distribution infrastructure throughout the country. Along with its national Komunist ( Communist ), published in Kyiv, the Party issues Kommunist Donbassa ( Donbas Communist ), Serp I Molot ( Hammer and Sickle ), Kommunist Kyiivschiny ( Kyiv Communist ), Radyansḱa ( Soviet Luhansk ), Vynitsḱa Pravda , Cherkasḱa Pravda , Kommunist Podillya , Radyansḱa Volyn' ( Soviet Volyn ), Pravda Melitopolya ( Melitopol Truth ), and many others, which are strongly opposed to the presidential party in power.

Other influential newspapers with party affiliation and financial support include the daily Tovarisch ( Comrade ), published by the Socialist Party of Ukraine, and Nasha Gazeta ( Our Newspaper ), which belongs to the Social Democratic Party of Ukraine, a close affiliate of the Communist Party of Ukraine.

A series of newspapers and magazines are produced by the radical nationalistic organizations and parties, such as the Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists, Narodnyi Rukh Ukraiiny, and Molodijnyi Natsionalistichnyi Kongres. Kievskie Vedomosti ( Kyiv Official Reports ), 100,000 copies, is owned by the Publishing House ZAO Kievskie Vedomosti and is controlled by the party Yabluko.

Silśḱi Visti ( Rural News ) is one of the major newspapers (665,000) for people living in rural areas. Until 2002, it was oriented toward the left political spectrum, and especially toward Selyanska Partiya (Peasant Party), which expresses mainly the political views and interests of the rural population. During 2000 and 2001, the newspaper received national and international recognition for its bold activities in defense of the freedom of press. Consequently, its circulation and popularity grew considerably.

Trade unions traditionally had numerous publications. However, in the 1990s their number significantly declined as the union movement in the country and union membership subsided. A large number of printed media addressing the young audience is heavily subsidized by the government and/or public organizations. These media include Molod' Ukrainy ( Ukrainian Youth ), Ukraiina Moloda ( Young Ukraine ), and GronoBunch of Grapes ). Much younger populations are served by Aist ( Crane ), Molodyi Bukovinets' ( Young Bukovinian ), Eirika , Peremena ( Lesson Break ), BarvinokEvergreenMalyatko ( Kid ), Ranok ( MorningSonyashnykSunflower ), and Vesela Pererva ( Funny Lesson Break ). The last one is published in English, Russian, and Ukrainian languages and enjoys great popularity.

Publications for women were always popular among the Ukrainian female population. In the 1990s, they became more Westernized with advertisements and information on feminist movement, Auto-lady , EvaVozḿ i Menya ( Take Me ), and Zhenskoe ZdorovýeWomen's Health ). International publications for women are also available.

The independent newspaper Dzirkalo Nedili ( Weekly Mirror ), published in the Ukrainian language and owned by the editorial staff, belongs to the moderate wing of the press because it tries to balance the publication of articles of various political groups. It also has an electronic version in the Russian and English languages. This newspaper is one of the few that tries to play by the market rules.

Some media is financed by international organizations. For example, European Union sponsors a Tacis program for developing free press in Ukraine. It subsidizes KP Publications, which owns the leading English-language weekly Kyiv Post and the web site Korrespondent.net . The U.S. Department of State provides assistance in developing independent electronic media in Ukraine through its ProMedia web site and sponsoring workshops and seminars for press workers.

Because oligarchs do not allocate large investments into printed media business, printing and editing technologies might be characterized as a combination of new Western technologies and obsolete Soviet equipment. Most Ukrainian media grew out of the state-planned Soviet infrastructure of subscription and distribution. The infrastructure and its services are still controlled by the state. Subscription and delivery of printed press is carried out by the state agency UkrPoshta (Ukrainian Post). In 2002, the subscription cost of newspapers per year varied from 19.8 hrivnas ( Kyivsḱa Pravda ), to 72 hrivnas ( Uryadovyi Kuríer ), and to 124 hrivnas ( Den' ). Elite publications, like 2000 and ii cost even more. Due to the frequent downfall of the national currency value and rising cost for the infrastructural services, some companies restrict subscription and sell newspapers and magazines at a "floating price" in private newsstands and kiosks or through part-time sellers.

Advertisement, once completely alien to the media, found its place onto the pages of newspapers and magazines; however, it did not play a significant role in oligarch-controlled media business. The price for private or commercial ads varies from one publication to another. Silśḱi Visti , the newspaper with the biggest circulation offers its services at 264 hrivnas per 20 square centimeters and 27,456 hrivnas for 2,080 square centimeters, which covers the whole page. The services of Golos , an independent newspaper in Donetsk range between 30 and 15,000 hrivnas.

It is worth noting that the purchasing power of the population considerably diminished after Ukraine became independent due to the general worsening of the economic situation. In 2002, according to the official data, 56.6 percent of population lived below the poverty line. The average salary in Ukraine was $67 a month, half of that in neighboring Russia or Belarus. Under these circumstances, many people cannot afford to subscribe even to a single publication.

Press Laws

The Ukrainian Constitution was adopted by Verkhovna Rada in 1996. Article 34 of the Constitution states:

- Everyone is guaranteed the right to freedom of thought and speech, and to the free expression of his or her views and beliefs;

- Everyone has the right to freely collect, store, use, and disseminate information by oral, written or other methods at his discretion;

- The exercise of these rights may be restricted by law in the interests of national security, territorial indivisibility or public order, with the purpose of preventing disturbances or crimes, protecting the health of the population, the reputation or rights of other persons, preventing the publication of information received confidentially, or supporting the authority and impartiality of justice.

For the first time in the twentieth century, the Constitution recognized the supremacy of human rights for the Ukrainian citizens, freedom of expression, and the right to have an access to public information. The journalists whose freedoms were restrained in the Soviet Ukraine for most of the twentieth century by the ideological control of the central and local party committees received guarantees for expressing their views and opinions on political, social, economic, and other issues of professional interest.

Verkhovna Rada also passed several laws, which determined the governing structure of the mass media and created legal foundations for their work. The laws covered: TV and Radio Broadcasting, National Council of TV and Radio Broadcasting, Information, Advertisement, Printed Information (Press), Radio Frequencies Sources in Ukraine, State Support of Media and Social Security of Journalists, Procedure of Coverage of Activities of the State Power Bodies, and of the Bodies of Local Self-governance, and System of Public TV.

Though the laws guarantee the right of journalists and reporters to obtain information open to the public, outline the procedure of the appeal against the officials who deny an access to it, and establish the due process for the defense of citizens' rights to information, many provisions of the laws are not widely accepted, approved, or observed in the society. Some articles of the laws are considered by journalists controversial and even undemocratic. The registration of printed press and electronic media is performed by the Ministry of Information of Ukraine.

Censorship

The Ukrainian constitution ruled out the censorship for which the former Soviet Union was notorious during the years of Communist rule. The Article 15 of Chapter 1 states: "Censorship is prohibited." However, journalists in the late 1990s and early 2000s talked about internal censorship that rests in the minds of many journalists who are aware that they may lose their job or be fined, their salary may be reduced, or they may even be killed if they write or speak against those who control media and the media market or against the political party for which they work. Since 1992, some 18 journalists have been killed in Ukraine, and although their cases were never disclosed, it is widely believed among journalists, the political elite, and the citizens alike that their murders were politically motivated. The case of the journalist H. Gongadze, who wrote on corruption in the government structures and was found murdered in 2000, received international attention, but the case was never solved. As a reaction to the Gongadze case and to other similar cases, in 2001 President Kuchma issued the decree "On Additional Measures to Secure Unlimited Activity of Mass Media and on Further Affirmation of Freedom of Press in Ukraine," which in particular planned to provide social security to the families of journalists and reporters killed while performing their professional duty. However, a number of independent publishers and journalists expressed a concern that this decree was a mere political act to appease the European Parliament Assembly, which was to debate the issue of freedom of press in the country in 2001.

Internal censorship implies that the journalists and editors have to be very careful what they write to create only a positive image of the oligarch or the political leader who controls the newspaper. It undermines the professional ethics of the journalists, which are vital for the development of democracy and a free press.

The journalists in Kyiv and other big cities are in a better situation and can afford to criticize state officials due to the presence of international journalists, diplomats, and representatives of human rights organizations, but journalists in remote areas have to think twice what and how to write about local officials or local mini-oligarchs.

The independent press accused the party in power of threatening the opposition newspapers and of waging a repressive campaign against the companies that placed commercial advertisement in them. In 2001, on behalf of 14 independent newspapers of Ukraine, the editor-in-chief of the Grani ( Sides ) newspaper sent a letter to the European Parliament Assembly in which he expressed concern about the state's repressive actions toward the press that disclosed the criminal actions of state officials.

The closure of the independent television channel in the city of Nikopol', the invasion of the office of the Internet newspaper Obcom.net under the pretext of warrant for search of the bank located in the same building, sanitary inspections for detecting the increase of radioactivity coming from the electronic devices, and threats by telephone are some of the examples of pressure that have been used against journalists by the state and the oligarchs.

In 2001, Article 182 was added to the Criminal Law of Ukraine. It made illegal the "gathering, storing, using, and disseminating [of] confidential information about any person without his consent." The article is viewed by some journalists as a threat to the rights of journalists for independent investigation, whereas their opponents argue that it defends citizens' right to privacy.

Article 32 of the Ukrainian constitution, which states "the collection, storage, use and dissemination of confidential information about a person without his or her consent shall not be permitted, except in cases determined by law, and only in the interests of national security, economic welfare and human rights," has been used by courts to persecute journalists who tried to investigate corruption cases involving state officials.

State-Media Relations

The State Committee on Information Policy, TV and Radio Broadcasting plays an important role in the area of information in the country. Its vast responsibilities include legal, technical, technological, and economic assistance and control over state, public, and private media activities in the country. It develops policies pertaining to their operation, reviews legal procedures, drafts proposals for the President and Verkhovna Rada, gathers statistical data, represents the country in international organizations, and conducts negotiations with parties involved in international cooperation. It also grants consent for the appointment to office and the dismissal from office of the Chairman of the National Council of Ukraine on TV and Radio Broadcasting by the President.

The National Council of Ukraine on TV and Radio Broadcasting and its branches in the regions oversee on a daily basis the work of television and radio companies; grant, renew, and withhold licenses for broadcasting; and conduct a competition for channel ownership and radio frequencies. The Council oversees companies to be sure that they abide by the laws and other regulating documents. Four of its members are appointed by Verkhovna Rada and the other four by the President.

In post-Soviet Ukraine, the state lost its direct ownership over media. Only 9 percent of printed press and 12 percent of the television and radio companies belong directly to the government. The majority, 52.9 percent, of printed press belongs to private citizens. A large portion of media have party, corporate, or cross-ownership.

The relations between the state, business, and mass media are far more complex than they might seem. Despite the loss of direct control, state officials have preserved some powerful levers of pressure over the most influential and widely distributed mass media. The oligarchs also play a significant role in state-media relations, often being appointed to the state bodies which oversee media or being elected to the editorial boards or boards of directors of the companies.

The relations between the state and the press remain unstable and at times controversial and unclear. On the one hand, the government insists on doing its best to promote the freedom of press, proclaims its commitment to "European choice," democratic values, and market economy. On the other hand, it does little to ensure that media operate on the basis of the rule of law with courts being the major judge in criminal cases.

The work of the National Council encountered extraordinarily negative coverage by media professionals and by members of Verkhovna Rada, who accused its members and staff of manipulating the procedures for granting and revoking licenses of television and radio stations to further their political and economic interests. This was claimed by journalists in 30 lawsuits filed in 2002. The bureaucrats are also often accused by media for creating privileges, extorting bribes, and corrupting the system of free media market. In many cases, it is very difficult to prove their illegal methods because their management of media is based on the notorious Soviet-type "telephone law," not on the principles of free market. Their arsenal of legal methods included sending commissions from sanitary, electric, fire, or other departments to find a reason for shutting down a rebellious media.

In 2002, I. Oleksandrov, the Director of the TV Company in Donetsk, was assassinated. It is not clear whether it resulted from the clandestine war of economic clans in the region or the persecution of state officials for criticism, or both. In 2001, the state revoked the frequency 100.9 from the radio company Kontinent (Continent) and granted it to another radio company Oniks (Onyx). The general director of Kontinent believed the denial followed his criticism of the party in power. He issued a statement in which he claimed that he had received several telephone calls threatening him and his family and advising them to leave the country.

The media also expressed their dissatisfaction with limited opportunities to obtain official information and, in particular, with the violation of the law On Procedures of Coverage of the Activities of the State Power Bodies and of the Bodies of Local Self-governance. Their interpretation of the law included the right to have access to the sessions of Verkhovna Rada, meetings of the Cabinet of Ministers and other state bodies, and to broadcast them to public, which they were denied for a long time. Finally in June 2002 the issue was resolved to their satisfaction.

Another sensitive issue raised by the media is a law On Mandatory TV Debates During Election Campaign of the President of Ukraine and People's Deputies of Ukraine, passed by Verkhovna Rada in 2001. The journalists view the law as an opportunity to facilitate the involvement of the people in democratic process of election and to provide them with more complete knowledge about the candidates' election platforms. However, the law was not signed by the president.

Legally, the journalists have freedom to criticize any state official, however, due to the unspoken and unwritten law, they can complain of corruption but not mention specific individuals, criticize the Mafia but not implicate particular persons, criticize national or regional governing bodies but not their specific members, use harsh words to blame oligarchy but not investigate activities of any of them, and criticize the party of power but not mention its key players.

As Ukraine embarked on the road of free market, many publishing enterprises were not able to start their business without initial support from the state budget. The law On State Support of Mass Media and Social Security of Journalists allows the government to subsidize up to 50 percent of children's and youth media as well as scientific journals published by universities (above level III), research institutions, and media that promote the development of languages and culture of ethnic minorities. These publications are not to include commercial organizations or private party as sponsors. The State Committee on Information Policy, TV and Radio Broadcasting decides the eligibility of each publication for subsidies. In 2002, the Cabinet of Ministers uplifted restrictions outlined in the law. This step received harsh criticism by many independent journalists who evaluated it as a move toward strengthening the state control over media and creating additional opportunities for corruption and bribery among the state bureaucrats.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

The democratic Ukraine pursues the policy of opening the country to foreign mass media and providing conditions for the work of international correspondents, journalists, and reporters. According to the 1992 Agreement on Visa-Free Migration of the Commonwealth of Independent States Citizens, the correspondents from the former Soviet republics do not need to obtain a visa. The same procedure exists for the members of the European Union, Canada, Slovak Republic, United States, Turkey, Switzerland, and Japan in accordance with the Decrees by Ukraine's Cabinet of Ministers No. 750 of May 5, 2000, No. 1376 of September 1, 2000, and No. 192 of February 28, 2001.

International organizations like Reporters Without Borders, Freedom House, the Committee to Protect Journalists, and Amnesty International implement their watch functions for the observance of journalists' rights in the country. In 2000 annual report, the U.S.-based Committee to Protect Journalists placed Ukraine sixth on the list of top 10 persecutors of the media.

Jammed during the Soviet period, foreign television and radio stations freely broadcast in the country, or their programs are aired by the Ukrainian media. No restrictions on foreign publications exist, except those that promote hatred, racism, pornography, or threaten the security of the country.

News Agencies

Until 1991, Ukraine had one republican news agency that monopolized all information. The complex state, social, political, economical, and cultural developments of a new country engaged the emergence of diverse information agencies addressing novel demands and challenges. Among the 15 major agencies operating in Ukraine, the largest and most influential of them include: Derzhavne Informatsiine Agentstvo Ukraiiny, DINAU (State Information Agency of Ukraine), the oldest Ukraiinsḱe Natsionalńe Informatsiine Agentstvo (Ukrainian National Information Agency) founded in 1918 as a part of the TASS media agency of the Soviet Union; the recently created ones Expres-Inform, Iterfax-Ukraine, Rukh Pres, Ukraiinske Nezalezhne Informatsiine Agenstvo Novyn (Ukrainian Independent Information News Agency), Ukraiinsḱa Nezalezhna Informatsiina Agentsiya "Respublika" (Ukrainian Independent Information Agency "Republic"), and Ukrainsḱi Novyny (Ukrainian News). These agencies disseminate official and general public information and information services. Avesta-Ukraiina, Groshi ta Svit (Money and World), Infinservis, Ukraiinsḱyi Finansovyi Server (Ukrainian Financial Server) agencies provide analytical information and services about the conditions of financial markets, Inforbank agency distributes services related to banking and stock exchange matters. Many agencies became members of international alliances of news press agencies and have correspondent bureaus in all 26 regions in Ukraine and in 17 other countries.

Along with the domestic information agencies, there are a number of international news bureaus in Ukraine: Associated Press and United Press International (United States), Agence France Presse (France), Reuters (United Kingdom), Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (Canada), ITAR-TASS (Russia), Information Agency Novosti (Russia), Belopan (Belarus), and Polska Agencja Pracowa (Poland).

Broadcast Media

According to the Unified State Register of Enterprises and Organizations of Ukraine, there were 752 TV and radio stations registered in Ukraine in 2001. The independent media estimated that a large number of radio stations broadcast illegally, without licenses.

The largest TV and radio network belongs to Derzhavne Tele Radio Ukraiiny (State TV and Radio of Ukraine), which controls the national television channels UT-1 and UT-2, National Radio Company of Ukraine, the Promin radio program, 26 regional state television companies, Sevastopol' and Kyiv regional state television-radio companies, and the television-radio company Krym (Crimea).

The study of Socis-Gallap shows that the largest portion (98 percent) of Ukraine is covered by the television signal of the state UT-1 Channel. It is the most influential in the rural areas with a significant Communist electorate, which has nostalgic sentiments for the Soviet past. The European Institute of Media monitored the parliamentary elections in Ukraine in 2002 and came to the conclusion that the state-controlled television network, especially the state channel UT-1 allocated over 50 percent of news time to the pro-presidential block Za Edynu Ukraiinu! (For Unified Ukraine!). The opposition political block, Nasha Ukraiina (Our Ukraine), and the Timoshenko block were covered mainly in negative terms on this channel.

Eighty-five percent of the country's territory is covered by the state UT-2 Channel. The television broadcast of the UT-3 Channel Inter reaches about 60 percent of the country. Despite its extensive coverage of the territory, UT-1 Channel and UT-2 Channel are less popular and their ratings are lower than those of UT-3 Channel Inter.

The Channel Inter, a leader on the media market, was sponsored in 1997 by several companies, organizations, and individuals. The Russian television company ORT was the biggest financial contributor. However, its influence on the policy of Inter became rather limited at the beginning of the 2000s. It is a very modern, well-equipped company with a number of correspondents in Kabul, Moscow, and New York. Many of the employees belong to the Social Democratic Party of Ukraine, and they are criticized for biased coverage of other political parties.

Non-governmental television companies include ICTV, tele-radio company Zolotye Vorota (Golden gate), TK TONIS (TV TONIS), and Norma (Norm). Among the most popular TV channels are 1+1, Novyi Kanal (New Channel), and CTB. The largest private channel, 1+1, was initially sponsored in 1996 by the Central European Media Enterprises Ltd., which provided significant financial support to the media of Slovakia, Slovenia, and Romania. In 2002, it owned 30 percent of the channel stock of the 1+1 channel.

Novyi Kanal developed fast in the late 1990s and by 2002, it had gained great popularity, especially in the southern region of the country. ICTV enjoys popularity (12 percent of the audience) in the center of Ukraine. Most investments come to the channel from Russian businesses. In the 2002 parliamentary elections, the Novyi Kanal and CTB channels were recognized by the European Institute of Media as the most neutral channels in covering the campaign. ICTV, mostly financed by the U.S. Story First Communication, enjoys recognition among the professionals as the most rapidly developing political TV. TK TONIS, the first national independent television company, founded in 1989, is also a successful company. Its network covers 60 percent of the country.

The following independent radio stations enjoy greater popularity among the younger audience due to a strong focus on entertainment, sports, and tourist information: Gala Radio, Music Radio in Kyiv, Slavutich and Bulava radio stations in Kherson, and Donetskie Novosti, Evropa Plyus, and Radio DA! in Donetsk.

The non-governmental television and radio companies exceed by several times the amount of broadcasting time by the state companies. For example, in Kyiv, the proportion is one to five in favor of private and collectively owned companies. The greatest number of TV and radio broadcasting companies are concentrated in Kyiv (296), Kharkiv region (181), and in Volyn' region (11).

Most of the people of Ukraine can also receive ORT, RTR, and NTV channels from Russia. Their accessibility to the Ukrainian population diminished because of some restrictive policies and this caused concern among the Russian minority. According to the poll conducted by the Public Opinion Foundation in 2002, only 61 percent (98 percent during the Soviet period) of its respondents had access to Russian television channels.

In 2002, Ukraine launched the project Gromandsḱe Movlennya (Municipal Broadcasting) for TransCarpathia, the western part of the country, to facilitate broadcasting in Roma, Rumanian, Hungarian, and other languages to the ethnic minorities of the area.

In 2000, Verkhovna Rada passed a law On the Establishment of the System of Public TV and Radio Broadcasting in Ukraine. According to the law, the National TV and Radio Company was to provide assistance in creating independent public television and radio company by the year 2002. However, the law did not go into effect due to the struggle for the influence on television and radio between the oligarchs and state structures.

Nearly half of the TV audience (49 percent) prefers to watch news programs produced by the Ukrainian companies, especially the local ones. In 2002, in accordance with polls, TCN, UTN, Panorama , Fakty ( Facts ), Reportyor ( Reporter ), and ViknaWindows ) were the most popular news programs.

Ukraine has a highly developed system of wire radio broadcasting. However, FM radio stations have received greater development in the recent years.

To stop the violation of rights on intellectual property, which became a problem in post-Soviet Ukraine, the Copy Right Agency was established. In 2002, the agency developed a system of monitoring television and radio programs and signed agreements with five television, four radio companies, and 5,000 individuals on protecting their copyrights. It also plans to open its branches in the regional capital cities.

Electronic News Media

In 2001, according to some expert evaluations, there were over 300,000 Internet users in Ukraine. The development

The electronic media face many problems similar to those of other media. Due to the cost, less than 2 percent of the population has access to electronic media. Electronic media are also confronted by the government's attempts to take control over them via licensing. However, authorities realize that if they introduce such control, then the electronic media will abandon the domestic servers for the foreign ones, and the state will lose control. Electronic media have yet to become a major actor on the political arena, especially at the local rural level.

The country's significant Web sites include the Sputnik Media Group ( http://sputnikmedia.net ), which is a part of the KP Publications company. Sputnik Media owns two electronic newspapers, Korrespondent.net and Bigmir.com , both of which have gained acknowledgment as serious publications. The Internet newspaper, Ukrainsḱa Pravda , ( Ukrainian Truth ; http://pravda.com.ua ) is considered an opposition publication. It became popular after the murder of its first editor H. Gongadze.

The online press has received a significant impetus for its development in the 1990s and 2000s with the international assistance. For example, Sapienti , a Ukrainian-U.S. online journal, sponsored by the U.S. Department of State and IREX in 1998, publishes information on a variety of social, cultural, and educational issues in and out of Ukraine.

Education & Training

Ukrainian institutions of higher learning have developed an effective system of preparing journalists and other professionals for the mass media. Their curricula include the comprehensive study of legal, theoretical, and practical components as well as the study of the current world press. However, despite the impressive changes in the curriculum, some basic features of Soviet journalism and especially economic functioning of media remain unchanged. Like other former Soviet republics, Ukraine struggles with the legacy of the Communist journalism and its ethics. The most popular institutions that train mass media professionals are located in the cities of Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Dnipropetrovsk.

In the Soviet Ukraine, most of the journalists received their education at the College of Journalism of the Kiev University. The College was the major venue for getting a job as journalist. After Ukraine became sovereign, the University was renamed the T. G. Shevchenko National University, and the College was transformed into the Institute of Journalism. The Institute graduates 140 to 150 new journalists every year. However, 70 percent of them find a job in fields unrelated to media. The graduates of other majors from Ukrainian universities also join the media core.

There are over 30 organizations that claim to defend the rights of the journalists and other media professionals. The largest is the Natsionalńa Spivka Zhurnalistiv (National Union of Journalists), which became a member of the International Federation of Journalists in 2002. In 2001, during the parliamentary election campaign, a group of journalists created the Commission on Journalist Ethics. The journalists were disappointed with the way the National Union of Journalists represented and defended their interests in the government and public organizations and were also worried by the lack of professionalism among journalists. The Commission adopted the Code of Journalists for Clean Elections signed by 100 journalists and editors of national and regional press to secure objectivity in covering and informing people about Verkhovna Rada election campaign. However, some members of the commission became candidates for the parliament or joined some political parties' campaigns, thus making the commission's work less effective. When voters rejected most of the candidates heavily advertised by media during the 2002 parliamentary elections, the crisis of trust for media on the part of the general public became evident. The members of the commission learned their lesson and resumed their efforts in promoting principles of unbiased coverage of events in the press. They also planned to combat what they called dirty technologies used by some journalists and reporters who intruded into private lives of individuals they wrote about.

The Association of Employees of Mass Media unites professionals from other sectors of media business. Ukraine inherited the Soviet traditions of remunerating mass media professionals. The highest of them is The Honored Journalist of Ukraine award granted by the President of the country on the national Journalist Day or the Day of Radio, TV, and Communication Employees holidays. The Ukrainian journalists also celebrate the World Press Freedom Day. Ukraine is a member of the Association of National Information Agencies of the Commonwealth of Independent States.

Summary

From 1991 to 2002, Ukraine achieved numerous accomplishments in democratizing mass media by adjusting to the free market rule, introducing electronic press, and educating critically thoughtful journalists. The country adopted the constitution and several laws that guarantee freedom of speech, information, and press, and protection from censorship. The greater variety in state and private media is better equipped to meet the needs and interests of the country's diverse population. Opposition media came out of hiding or was created to criticize authorities including the President. Journalists became more active in obtaining and delivering information. Themes and topics once forbidden by Communists for public discussion, as well as classified and commercial advertising found its way onto the pages of newspapers, television screens, and radio waves. People also began to receive access to international print, television, and radio sources.

Overall, however, the situation with media is sometimes described as "revolution unfinished." Mass media in Ukraine reflect the perils of the period of transition from Communism to democracy and from state-owned to free market economy, which are typical of many East European countries and former Soviet Union republics. The consequences of the dismantling of Soviet structures and economic recession exposed Ukraine to numerous challenges and problems. The intellectuals express concerns about the decrease of the analytical materials and the disproportionate increase in entertaining and sensational information. The future of mass media and the quality of journalism depend upon the competition among various influential, political, financial, and industrial clans which unfortunately is accompanied by corruption and crime as numerous parties struggle for control over print, television, radio, and electronic media.

To be truly free, mass media must gain independence from financial oligarchs, industrial magnates, parties, and state control in order to create structures that will lobby media interests in government and in Verkhovna Rada.

Bibliography

Khrushevsky, Michael. A History of Ukraine . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1970.

Kuzio, Taras. Ukraine: State and Nation Building . New York: Routledge, 1998.

Nahailo, Bohdan. Ukraine Resurgence . Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999.

Reid, Anna. Borderland: A Journey Through the History of Ukraine . Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1997.

"Soviet Ulkraine." Ukrainian Soviet Encyclopedia . Kiev: Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian S.S.R., 1969.

Szporluk, Roman. National Identity and Ethnicity in Russia and the New States of Eurasia . Vol. 2. New York: M. E. Sharp, 1994.

Tismaneane, Vladimir. Political Culture and Civil Society in the Former Soviet Union . Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharp, 1995.

Wanner, Catherine. Burden of Dreams: History and Identity in Post-Soviet Ukraine . University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1998.

Grigory Dmitriyev

Arina Dmitriyeva

If yes,please tell me how & who I may contact.

With great appreciation,

Adrian McNickle

Many things have changed since it is now 2011!