Zimbabwe

Basic Data

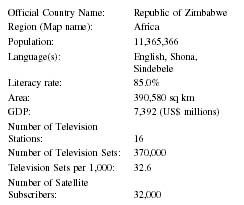

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Zimbabwe |

| Region (Map name): | Africa |

| Population: | 11,365,366 |

| Language(s): | English, Shona, Sindebele |

| Literacy rate: | 85.0% |

| Area: | 390,580 sq km |

| GDP: | 7,392 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Television Stations: | 16 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 370,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 32.6 |

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 32,000 |

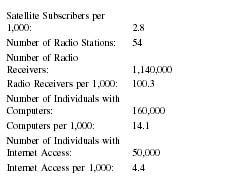

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 2.8 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 54 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 1,140,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 100.3 |

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 160,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 14.1 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 50,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 4.4 |

Background & General Characteristics

Zimbabwe is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. It is bordered by Zambia in the north, Mozambique in the east, Botswana in the west, and South Africa in the south. Many of its economic and transportation links are with these countries. Lack of its own ports and harbors forces Zimbabwe to rely on Mozambican and South African facilities; thus, its economy and politics have also been subject to ripple effects from its neighbors, especially South Africa and Mozambique. Outside South Africa, Zimbabwe boasts one of the most highly developed industrial infrastructures in sub-Saharan Africa.

Press freedom has had a long, tenuous existence in what today is known as Zimbabwe. The governments in power have often professed their commitment to press freedom. In reality, however, the communication media has suffered from contradictory tendencies, as political self-interest has too often ridden roughshod over the public's right to free and unfettered news and information. In the turbulent days before and during the Ian Smith regime, pre-publication censorship was commonplace. Since Rhodesia became the independent Zimbabwe on April 18, 1980, there has been no direct censorship. But there has been government control of the print and broadcast media. Editors have also engaged in self-censorship.

The Lancaster House Constitution of December 1979 became Zimbabwe's constitution when the country became independent from Britain in 1980. It is a Westminster-type document designed to promote multi-party democracy. The Declaration of Rights comes under Chapter 111 of the constitution. This section deals with the basic rights and freedoms of the individual, regardless of race, color, sex, political opinion, or place of origin. This includes the right to life, liberty, security of the person and protection under the law, and protection of the privacy of the home and other property.

Section 20 of the constitution guarantees freedom of expression; the right to receive, impart, and hold ideas and information without interference; and freedom from interference with correspondence. It is this part of the constitution that protects freedom of the mass media. Under normal circumstances, this provision seems to be a straightforward guarantee that Zimbabweans can receive, read, discuss, and share ideas, news, and information freely, without government control or interference. But this is not an unqualified right. For example, restrictions may be placed on the media, citizens, or on what is generally called civil society in the interests of defense, public safety, the economic interests of the state, public health, public morality, public order, or to protect the rights, freedoms, and reputations of other people or the private rights of persons involved in legal proceedings. Restrictions may also apply to protect or prevent the disclosure of confidential information or to maintain the authority and independence of the judicial system (courts, tribunals) or the House of Assembly.

A state of emergency, imposed in 1965 by the rebel Smith regime, did not lapse until July 25, 1990. It gave Prime Minister Robert Mugabe's post-independence government and its organs unlimited power to control the media and the citizens. It freely violated human rights. Government could, if it wanted, control what was published or broadcast. There was no appeal against such actions, which left the media largely cowed and controlled. Certain laws on the books, some inherited again from the minority Smith regime, such as the Law and Order (Maintenance) Act, also gave the government unlimited power over the media. Such laws gave the Zimbabwe police the power to allow or permit meetings or rallies. In reality, meetings of the ruling Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) were always allowed. Opposition meetings were hardly ever permitted, thus violating the spirit of the constitution, which guaranteed freedom of assembly and association.

The story of the media in Zimbabwe cannot be separated from the history of the troubled country. When, on November 11, 1965, Smith and his white minority Rhodesian Front party unilaterally declared the country independent (UDI) this was the culmination of a struggle, which started in the late 1800s when white settlers arrived in that part of Africa, to impose permanent white minority rule. UDI was a calculated attempt to ensure perpetual white control at the expense of the black majority. Ironically, this would accelerate the advent of black majority government.

Formal white control began in the late 1880s when Cecil John Rhodes, the British adventurer after whom the country was at one time named, sent emissaries north from South Africa. Rhodes became a politician and mining magnate in South Africa. His people sought mining rights from local chiefs. They succeeded in tricking King Lobengula of Matabeleland to sign the Rudd Concession, which gave Rhodes exclusive mineral rights to an area that, according to their interpretation, covered Zambia and Zimbabwe (formerly Northern Rhodesia and Southern Rhodesia). This concession eventually was used to make the area part of the British Empire.

In 1923 British South Africa Company rule over the country ended. It was replaced by internal self-government for the white minority. Again, Africans were not consulted. Whites controlled the country, however, Britain retained control over foreign affairs and matters dealing with African affairs. In theory Britain could veto any legislation passed by the Rhodesian Legislative Assembly, if it was unfair to the African majority, but this power was never exercised. When successive Rhodesian legislatures steadily whittled away African rights, on land and other issues, there was no British veto.

In the 1960s the Southern Rhodesian whites pushed for independence, which would retain control in white hands. But, under mounting pressure by African nationalists, the British backed off. It was under these conditions that Smith undertook UDI, which placed the country under virtual international ostracism, led to economic sanctions and eventually forced the country's African nationalists to opt for guerrilla warfare as the only way to end minority rule. During this time the country's media systems suffered unparalleled restrictions, including outright censorship. More than 30,000 people, mostly blacks, would die before Zimbabwe's birth.

In Zimbabwe in the 2000s, the government-controlled media regularly attacked their privately owned counterparts. The foreign media and foreign journalists have not been immune. The government controls the country's only radio and television stations, using them for partisan political propaganda, while opposition political parties and non-governmental organizations are routinely denied access to the airwaves. They can be attacked on the airwaves but are denied an opportunity to respond. The government controls six newspapers— two daily, two Sunday, and two weekly—all used as part of its arsenal for relentless, unanswered criticism and attacks against those who happen to hold political views differ from those of the ruling clique.

In addition, the government introduced a bill that seeks to prevent foreign journalists from being allowed to work in the country, and seeks the licensure and accreditation of domestic journalists for a year at a time, with the minister of information deciding who should/ should not be licensed and the government banning the media from publishing or broadcasting unauthorized Cabinet information.

Media History

Zimbabwe has some of the oldest newspapers in Africa. In June 1891, the Mashonaland and Zambesian Times , a hand-written paper described by one journalist as a "crude but readable cyclostyled sheet," was published. On October 20, 1892, The Rhodesia Herald replaced the Mashonaland and Zambesian Times as the country's major daily newspaper. The paper, since renamed The Herald , survives today as the country's oldest and biggest daily newspaper. But it has changed over the years. It was started by the Argus Company of South Africa. On October 12, 1894, the Argus Company chose to start a second newspaper, the Bulawayo Chronicle in Bulawayo, the country's second largest city. Today, these papers are the oldest in the country. The two papers supported the British South Africa Company in its quest to continue ruling Rhodesia.

The media in Rhodesia catered to the needs of the white settlers by ignoring news of interest to the African majority. Much of the early news was about events occurring in the metropolis, from politics to sports, while events on the African continent were ignored. The needs, aspirations, and hopes of the Africans were never published. However, news about crime by blacks was prominently covered. The media had not changed much by the time the country achieved its independence. Coverage was still geared mainly towards white readers and advertisers, which was not surprising since all top Rhodesian printing and publishing newspaper executives in Rhodesia were white, as were all the editors, copy editors, almost all of the reporters, and most of the advertising and circulation executives, which had important implications for the media at independence.

The media is important because it informs, educates, and entertains. It also fosters a common culture or propagates the ideas and theories of the country's political, economic, educated, ruling, cultural, and social elite. The media also allows those in power the ability to control what the media reports or what the masses will or will not now. Under ideal conditions, they can also provide twoway communication between rulers and their subjects. Thus, it seemed almost inevitable that the Mugabe government would move fast and decisively to acquire the means to control the electronic and print media. It was easy to take over the electronic media because under Rhodesian laws the broadcast outlets were already under government control. The Smith regime had been appointing the board of governors who oversaw the broadcast authority. Although in theory the electronic media were autonomous, in reality the Smith regime exercised effective political control, including guidelines that required that the African opposition be denied on-air access. The Rhodesia Broadcasting Corporation (RBC) was part of the Smith regime's propaganda machinery. After UDI, legislation was passed by the Rhodesian parliament imposing a fine of up to $1,500 or 2 years in prison on anyone who permitted any hostile broadcast to be heard in public. Pro-apartheid Radio South Africa replaced the British Broadcasting Corporation as the main source of external news. Smith himself admitted that radio was one of the most powerful tools in the ongoing "war for men's minds."

In a related development, author Julie Frederikse found a confidential RBC memo, dated August 28, 1978, signed by T. W. Louw, RBC's director of news, which listed a number of organizations that could not be mentioned by Rhodesian radio and television staff. These included, ZAPU (Zimbabwe African People's Union), ZANU (Zimbabwe African National Union), the Patriotic Front (an alliance of ZAPU and ZANU), the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANU's guerrilla wing), the Zimbabwe People's Liberation Army (ZAPU's military wing), and the Zimbabwe People's Army.

The Mugabe government learned its lesson well. It has continued its control of the electronic media, with the Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation, acting as a subsidiary of the government by denying access to the airwaves to opposition political groups, while giving the government and the ruling party unfettered access to the broadcast media. Even access to advertising on the electronic media is controlled. Government activities and pronouncements from the Mugabe (who has been in power since 1980) government are prominently featured on radio and television, while government opponents are hardly featured, except negatively or when being attacked. Pronouncements from President Mugabe usually lead radio and television news broadcasts, even when they involve nothing more than mundane events.

In reviewing the results of the 2002 presidential election, the Media Monitoring Project in Zimbabwe concluded that about 90 percent of all election stories carried on Zimbabwe television were about Mugabe or ZANU, or they were pro-government. There was no effort at balance or fairness. Additionally, even after the courts ordered the government to end its monopoly control over the broadcast media, no private individual or company was issued a license to launch radio or television stations that would compete with the Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation.

Influential Newspapers

The state-controlled Herald and Chronicle , the Sunday Mail and Sunday News , and the weekly Manica Post and Kwaedza/Umthunya are used regularly to propagate government and ruling party policies and propaganda and to attack government opponents, both domestic and foreign. Government opponents are rarely featured in the state-controlled print media, except in a negative manner or when reporting news of their arrests or when they are attacked by government officials or their surrogates. During the 2002 election Mugabe was pitted in spirited contests against Morgan Tsangirai, leader of the opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC); the only publicity for the Mugabe opponent was found in the privately owned Daily News , now the country's leading daily newspaper; in the weekly, privately owned Independent and Financial Gazette ; and in the privately owned Sunday Standard . These publications regularly use their editorial pages to denounce the government and their news pages are often filled with critical stories and comments. The state media regularly returns the fire, but, unlike the state media, the private media also carries some stories critical of opposition groups. The state print and broadcast media never carries anything critical of the government.

The Daily News is the most influential newspaper in the country. It boasts a circulation of more than 100,000 and growing, despite having its printing press destroyed. It is seen as the voice of those who oppose Zimbabwe's government, although it is careful not to be seen as blatantly anti-Mugabe or pro-MDC. It also is under relentless attack by ZANU and its supporters. The Herald , once the most influential newspaper in the country, has seen its circulation drop from a peak of 132,000 to between 50,000 and 100,000. Some advertisers and readers boycott it because of the perception that it is blatantly and slavishly pro-Mugabe and pro-ZANU. The privately owned Financial Gazette has a readership between 50,000 and 100,000. The Independent, The Standard , and The Sunday Mail also carry some weight, the first two among opposition groups and the latter as the govern-ment's chief weekly mouthpiece.

Censorship

Under the colonial regime, there was censorship of the media and the entertainment industry. Movies, books, and newspapers were censored, forcing The Herald to resort to leaving blank spaces in its news columns in the 1960s to indicate where stories had been banned or censored. The present government has not gone that far, but it has appointed editors who follow government prescriptions; those who annoy the government are fired or moved elsewhere. Self-censorship also is commonplace among the state-owned media. Further, the minister of information has inordinate powers to appoint and fire editors and to punish those who violate government policy or fail to use the media to promote government policy and propaganda or who publicize the views of government officials.

State-Press Relations

Under the Smith regime, the broadcast media was under strict government control, but the regime did not try to take over the news media. Government broadcasters were under directives to refer to Mugabe and his guerrilla counterpart Joshua Nkomo as "terrorist leaders" or "leaders of terrorist organizations." Their political parties were similarly referred to as "terrorist" movements and their followers, especially the guerrilla fighters, were called "terrorists." Ironically, after independence, the Mugabe government used similar tactics by referring to its opponents as "bandits" and "terrorists."

The Mugabe government quickly appointed its own board of governors, many of whom had no media backgrounds, to oversee the renamed Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation (ZBC). In 2002, ZBC ran the country's television and radio stations. Government funding from the Ministry of Information subsidizes the electronic media, which also depends on annual license fees that must be paid by all Zimbabwe residents who own or rent radio and television sets.

The Mugabe government also established the Zimbabwe Mass Media Trust (ZMMT) to set long and short-range policies for all the Zimbabwe media. Initially, the board set to oversee the ZMMT was a cross-section of Zimbabweans of all political and economic stripes. Over the years, however, the board has become increasingly political—dominated by those with strong ZANU-PF connections.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

In the past, foreign journalists were welcome to work in Zimbabwe. This, however, has been changing. In early 2002, American journalist Andrew Meldrum, a longtime resident of Zimbabwe, was charged under the Access to Information and Protection of Privacy Act (AIPPA) for publishing a false story about a man who had allegedly been beheaded by government supporters. After he was acquitted, the government moved to deport him. A court stayed the deportation. (Two Daily News journalists face charges under the AIPPA for the same story.) Several journalists have been denied permissions, visas, and work permits. A British Broadcasting Corporation journalist was deported last year. A number of South African journalists have also been arrested and forced to leave the country.

Sections of the AIPPA that apply to foreign and domestic journalists do not allow journalists to acquire and disseminate information. The AIPPA is being used to force the foreign media to employ Zimbabweans as journalists. Despite its innocuous sounding name, many independent and foreign journalists see the AIPPA as a thinly disguised attempt to control and intimidate them.

Broadcast Media

Zimbabwe has four main radio channels. Radio 1, broadcasting in English, is a general station that covers

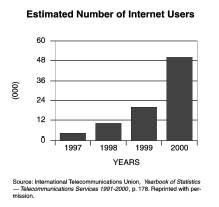

As of 1997, there were 16 television stations for only 370,000 television sets owned throughout Zimbabwe. Online access has started to bloom with six Internet service providers and 30,000 users as of 1999.

Summary

The future is not very bright for Zimbabwe's media. The government seems determined to retain its strangle-hold on the six newspapers in the Zimpapers stable. Without a change of government or ideology, Zimpapers, ZIANA, and ZBC are likely to remain instruments of government propaganda, dependent on government subsidies for their survival. It is unlikely that Mugabe or ZANU would agree to allow the state-owned print and broadcast media to break from state control. The Access to Information and Protection of Privacy Act (AIPPA) allows the government to license and accredit journalists. Those who violate its provisions, mainly in the private media or among foreign journalists, face fines and up to 2 years in prison. So far, 12 journalists have been charged under the AIPPA, many charged with publishing false information. None of them have been from the state media, even though opponents have accused state journalists of publishing false information.

The private media has struggled to survive under difficult conditions. Generally, all private forms have been vibrant. They have been critical of the government and the state media. They have tried to play a watchdog role by holding the government accountable for its actions. They have published stories that the state media dare not touch and have also been outlets for the views of those who oppose the Zimbabwe government. Whereas the government media has lost advertising and circulation revenue, the private media has increased circulation and advertising dollars. The AIPPA is, however, likely to make life more difficult for the private media and private journalists, as well as for the foreign media.

Bibliography

Austin, Reginald. Racism and Apartheid in Southern Africa: Rhodesia .Paris: The UNESCO Press, 1975.

Faringer, Gunilla L. Press Freedom in Africa . New York: Praeger, 1991.

Freedom in the World 1989-1990 . New York: Freedom House, 1990.

Good, Robert C. U.D.I. The International Politics of the Rhodesian Rebellion . Princeton University Press, 1973.

Hachten, William A. Muffled Drums: The News Media in Africa . The Iowa State University Press, 1971.

Kumbula, Tendayi. "Press Freedom in Zimbabwe." In Press Freedom and Communication in Africa, eds. Festus Eribo and William Jong-Ebot. Africa World Press, Inc., 1997.

Liebenow, J. Gus. African Politics: Crises and Challenges . Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1986.

Martin, Phyllis M., and Patrick O'Meara, eds. Africa . Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986.

Merrill, John C. Global Journalism: A Survey of the World's NewsMedia . New York and London: Longman, 1991.

Muzorewa, Abel T. Rise Up & Walk . Nashville: Abingdon, 1978.

Mytton, Graham. Mass Communication in Africa . London: Edward Arnold, 1983.

Nordenstreng, Kaarle, and Lauri Hannikainen. The Mass Media Declaration of UNESCO . Norwood, New Jersey: Ablex Publishing Corp., 1984.

Ochs, Martin. The African Press . The American University in Cairo, 1986.

Press Freedom in Zimbabwe . Harare, Zimbabwe: The Willie Musarurwa Memorial Trust, 1993.

Rusike, E. T. M. The Politics of the Mass Media . Harare, Zimbabwe: Roblaw Publishers (Pvt) Ltd., 1990.

Stevenson, Robert L. Communication, Development and the Third World . New York & London: Longman, 1988.

Ungar, Sanford J. Africa . New York: Simon and Schuster, 1985.

Wiseman, John A. Democracy in Black Africa . New York: Paragon House Publishers, 1990.

Zimbabwe: Wages of War . New York: The Lawyers Committee for Human Rights, 1986.

TendayiS Kumbula

On a visit in 1998 we went and visited at the plant,met with William, since then I have attempted to make contact with William ,to no avail.

William was well known and highly respected within the Trade.

Reading your excellent article not only brings back memories but hope that you might be able to assist in enlightening me on the whereabouts of William and his Family.

With best regards.

Lloyd Smith I will send pictures of President Mugabe and I at the Commisioning of the Press, if you wish LDS

Otherwise good work