Bosnia-Herzegovina

Basic Data

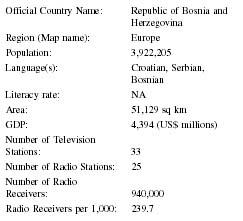

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| Region (Map name): | Europe |

| Population: | 3,922,205 |

| Language(s): | Croatian, Serbian, Bosnian |

| Literacy rate: | NA |

| Area: | 51,129 sq km |

| GDP: | 4,394 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Television Stations: | 33 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 25 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 940,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 239.7 |

Background & General Characteristics

Until the late 1990s, most Bosnians were identified simply as Bosnians. However, since the end of the war and the division of Yugoslavia, Bosnians have become more divided along ethnic and religious lines. Most (more than 95 percent) speak the same language, Bosnian or Serbo-Croatian, and most share the same ethnic racial background. Where they are divided is in their religions. Bosnians of Catholic faith, or whose ancestors were Catholic, are identified as Bosnian Croats, and make up 17 percent of the population. Those with Eastern Orthodox backgrounds are Bosnian Serbs, and comprise 31 percent of the population. The largest group is the Muslim Slavs, descendent from Christian Bosnians who approximately 500 years ago adopted Islam, with 44 percent of the population. Although the country is increasingly secular, strong hatred remains between the three groups.

Bosnia-Herzegovina's dynamic press has been characterized by diversity and change, and has been extremely influential in the political development and public opinion of the country, although it still has not been effective in the citizenry's understanding of its rights and national identity.

The Bosnia-Herzegovina (BiH) press had during the early 1980s potential to become an independent, vibrant and a free voice of the people; however, media in general became a propaganda tool during the war which ultimately split Yugoslavia. The media became dependent, not only on political bankrolls, but upon the fast and loose reporting style of the propaganda machine. Even now, accuracy and fact checking are not widely valued, and most print and electronic media remain extremely slanted and divided politically and ethnically. Since 1995, and the signing of the Dayton Peace Accord, BiH has remained mainly peaceful, but journalists have had some difficulty adjusting to press freedoms and their new roles in post-war news gathering and delivery. Readers are as reluctant to cross over to objective media as reporters are to adopt fair reporting styles and policies necessary to establishing a democracy. The tendency on the part of readers has been to continue to purchase newspapers and magazines which are aimed primarily at their specific political party or ethnic/religious demographic.

After the war heavy nationalist attitudes took hold. Fear and ethnic and religious bigotry negatively impacted the press, even though prior to the 1990s, the press had been very diverse despite a long history of dictatorship and censorship. From 1945 to 1990, although religious freedoms were terribly impacted throughout Yugoslavia (Muslims, Christians and Jews alike were banned from public worship), cultural freedoms (an active press included) were fully supported both philosophically and financially by the government. A long economic boom in the Communist country also helped support emerging media. Unfortunately, during the time of political unrest and war, the media also became a tool for differing political parties. Parties and governments supported media that espoused their political views, and punished, in direct financial actions as well as intimidation, those who did not. Those that complied became dependent on the political funding. They also became dependent upon easy-to-get information, and never questioned its truth or validity. Even though journalists in BiH can take advantage of Freedom of Information laws, many do not because they are largely untrained in the concept and practice.

Although technically BiH has a free, or partially free, press guaranteed by its Constitution, in practice the press is still heavily controlled by the government, and by advertisers or vendors who will not support publications with editorial opinions that differ from their own ideologies. State-supported businesses are prohibited from advertising in independent, non-government newspapers and electronic media.

The BiH media landscape is highly saturated. In a country of approximately 4 million, there are 376 media groups in BiH: 138 newspapers and reviews, 168 radio stations, 59 television stations and 11 news and photo agencies. Although on the surface those figures are impressive for a country that is still relatively new to having and supporting a free press, they represent a significant decrease from the BiH press' most active and diverse period. Ironically, the war which divided Yugoslavia (into the current countries of BiH, Croatia, and Slovenia) nearly destroyed the media. Newspapers were, before the war, largely subsidized or completely supported by the government. In the age of democracy and a free press, many businesses, particularly during lean economic times, have found survival impossible. For example, in Sarajevo alone there are three daily newspapers and five newsmagazines. The over-saturation is forcing the media industry to consolidate, but the independent media in particular are ill equipped to deal with consolidation. Many of the media are over-or under-staffed, and many are managed poorly and lack proper technology. Further, limited understanding of still-developing media laws and the media's new and emerging role in a developing free society negatively impacts publishers' ability to effectively manage their businesses. The newly-created press laws made survival even more difficult as censorship, sometimes blatant and at other times subtle, has remained very much a reality.

In 1991 there were 377 newspapers and publications. The diverse media was a key player in the early stages of the socialist system's disintegration. Young journalists in the early 1990s launched opposition newspapers, and in the fall of 1990 the first multi-party elections were held in Yugoslavia. During that tumultuous time, the press was fairly free-swinging, and although it had been censored and controlled previously, during the war years, papers from a wide variety of political slants and ethnic backgrounds published and survived, or even in a few cases flourished. However, after the country's first free elections, many newspapers were punished by government officials who had faced opposition in the media. Newspapers that espoused philosophies opposite theirs, or who had dared criticize candidates and officials, were suddenly raided, and audited and fined. In other cases journalists were sued for libel, threatened, or physically assaulted. However, as professional associations develop, media professionals will benefit from more education and legal support.

The BiH media is still largely under the influence of the government, and of political parties, and most independent newspapers suffer lower circulation and fewer resources. Dnevni Avaz had been prior to 1999 controlled mainly by the Party of Democratic Action ( Stranka Demokratske Akcije , SDA), but distanced itself and adopted more fair and professional reporting standards. It remains the most widely circulated daily paper in BiH. Dani and Slobodna Bosna are the most influential independent magazines in the BiH federation. The weekly newsmagazine Reporter is the most influential independent weekly.

Two true independents, Oslobodjenje and Vecernje Novine , combined have lower circulation with 25,000 readers than their former SDA supporter Dnevni Avaz with 30,000 readers.

Economic Framework

Bosnians are still suffering the aftermath of the war. Unemployment is high—nearly 50 percent—and earnings are low. Many major cities are being rebuilt from ruins after being bombed. Prior to the war, employment was high in the mainly industrial country. Earnings were fair in the Bosnian region, though not as high as in the former Yugoslavia's northernmost area, Slovenia.

Press Laws

Government officials are still in the process of developing media and press laws. Most of the media and press laws were formed in 1995 with the signing of the Dayton peace agreement. The Constitution provided for a free press and by law prohibited censorship, but did not properly protect media professionals or provide for adequate flow of information between state and press. Further, the financial structure of most media was not yet ready to sustain a free press and break free from government support and subsidy.

Following the Dayton agreement, the government failed to comply with free press provisions, and it was not until the late 1990s that the government began to view seriously the importance of a free press. The shift in attitude came only after years of pressure from European and American democratic countries.

In 1999 the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights directed the BiH government to decriminalize libel and defamation. Prior to that, libel laws were so restrictive that journalists and publishers could be sued for exorbitant amounts of money for honest criticism of the government and its leadership. Steep fines and court actions created a serious chilling effect in the media, and virtually prohibited the media from engaging in honest journalistic pursuits.

In 1999 and 2000, the process had come to a halt, and the media was largely adhering to the draconian laws imposed in pre-war Yugoslavia. The former laws restricted the information flow from the government to the media.

Even newer laws negatively impact the media. The laws were designed to protect the country's current government in light of the threat of NATO military strikes. Under the Public Information Act of 1998, the public and government officials can still sue the media for publishing material that is not patriotic, or is "against the territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence of the country." Further, rebroadcasts of foreign media and news services are strictly banned.

The law, which has been criticized as "extremely vague and selectively enforced," makes it "practically impossible to engage in any type of journalist work," according to the U.S. State Department. Further, libel laws only apply to independent newspapers, not to government-sponsored papers. Approximately 25 percent of BiH newspapers are independent and some of the state-run papers are partly privatized.

When NATO bombing began in 1999, independent media outlets were shut down completely. Journalists were not allowed to report on the military, or on casualties, and the media was generally censored during that time. When the bombing concluded, more than one third of all the radio and television stations failed to resume operations.

The laws are changing slowly. In July 1999, the United Nations called for new legislation to deal with defamation and libel. In 2000, a new Freedom of Information law was passed, guaranteeing access to official government records.

Censorship

Although technically BiH has a free, or partially free, press guaranteed by its Constitution, in practice the press is still heavily controlled by the government, and by advertisers or vendors who will not support publications with editorial opinions that differ from their own ideologies. State-supported businesses are prohibited from advertising in independent, non-government newspapers and electronic media. Further, the media professionals themselves have had some difficulty adjusting to the concept and practice of a free press, designed to educate rather than to persuade readers or create nationalist sentiment.

Under the Dayton Accords, peacekeeping forces have the authority to monitor and penalize the news media. Although used rarely, it remains as a pressure with which journalists must contend. Two agencies have been developed for regulating print and electronic media. In 2000, the Council for the Press was formed. The Communications Regulatory Agency (the CRA) had been operating for several years prior to the print counterpart's development.

The primary difference between the two is that the CRA may discipline outlets while the Council has no sanctions at its disposal, and cannot, for example, prevent a paper from printing. The CRA, however, can close outlets which are in violation of media laws.

The Council oversees voluntary compliance with laws and journalistic standards, while the CRA was given the task of cleaning up the saturated and cluttered broadcast scene. Broadcasters who continue to air inflammatory and unprofessional programming are shut down. While it seems backward that a government agency is given this power after the war (during the war the press had free reign to print or broadcast whatever it pleased, and was often encouraged to become the mouthpiece for various political parties) the goal is to establish a fair, democratic and professional press.

However, media professionals in BiH, accustomed to political divisiveness and bickering, complain the CRA is too heavily controlled by foreign entities and adheres too strictly to foreign press objectives, which are generally more similar to the western world's concept of a free and democratic society. They have therefore resisted compliance with the new standards and media laws.

Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Legislation passed in 1998 guarantees the press access to public information, however, they must request in writing the documents they need. Although the government has only recently began complying with FOIA legislation, perhaps the even greater issue is journalists unfamiliarity with the types of information available to them, and the process for requesting such material. The shortcomings on the part of the media professionals are generally caused by lack of training and reporting in a free press society.

Attitude Toward Foreign Media

Media professionals and consumers alike are distrustful of foreign media. During the war, foreign media professionals fell for different public relations efforts, though the BiH media professionals fell just as hard.

Most notably was the news coverage generated by the American public relations firm, Ruder Finn, hired on behalf of Serbia's enemies. The firm has been accused by some of exaggerating and dramatizing circumstances and events during the war, which foreign journalists, particularly Americans, reported as fact. According to National Post reporter Isabel Vincent, one of the firm's best customers was Kosovo, which paid the firm more than $230,000 in six months.

"For that Ruder Finn focused its efforts on building international support for actions designed to prevent 'ethnic cleansing' by Serb forces in Kosovo," Vincent reported. Bosnian journalists and readers alike grew wary of foreign media, and Vincent quoted one Bosnian reporter as saying, "You people in the international press really don't know what you are writing about. You buy into to the whole Ruder Finn line, and you don't really do any independent reporting. That's the reason I really don't believe in a free international press."

Broadcast Media

The largest broadcasters in BiH are Radio Television Bosnia and Herzegovina (RTV BiH) and Radio and Television of Republika Srpska (RTRS). According to the U.S. State Department, the international community launched the Open Broadcast Network (OBN) in 1997 as a cross-entity broadcaster and source of objective news and public affairs programming. However, only a minority of viewers watches the OBN as their primary source of news. Independent outlets include TV Hayat, Studio 99, OBN Banja Luka affiliate Alternative TV, and other small stations throughout the country. Of the smaller stations, most of which were municipal stations prior to 1995, some have been partially privatized, but none have been fully privatized, and as yet the ownership status of nearly all is still unclear.

The matter of privatization will likely be sorted out in the first part of the twenty-first century. The media industry began a restructuring in July 1999, and it has yet to be fully implemented. Under the restructuring the state-run broadcast industry was to be liquidated, including the liquidation of RTV BiH, and to create a statewide public broadcasting corporation, The Public Broadcasting System of Bosnia and Herzegovina (PBS BiH). Elements of OBN will be incorporated into PBS BiH, but details have not yet been fully determined.

As part by the OBN of the restructuring new guidelines have been established and "programming must be based on truth, must respect human dignity and different opinions and convictions, and must promote the highest standards of human rights, peace and social justice, international understanding, protection of the democratic freedoms and environment protection."

Radio broadcasting in BiH is diverse. According to the State Department, opposition viewpoints are reflected in the news programs of independent broadcasters. Independent or opposition radio stations broadcast in BiH, and Radio Pegas report a wide variety of political opinions. Local radio stations broadcast in Croat-majority areas, but they are highly nationalistic. Local Croat authorities do not tolerate opposition viewpoints. One exception is Studio 88, in Mostar, which broadcasts reports from both sides of the ethnically divided city.

The Independent Media Commission was established in 1998 and is empowered to regulate broadcasting and other media. The IMC licenses broadcasters, determines licensing fees, establishes the spectra for stations, and monitors adherence to codes of practice. The IMC also controls punishment of broadcasters for noncompliance. Warnings, fines, suspension and termination of licenses, equipment seizures and shut-downs are among their tools for controlling the broadcast media.

Although incidents of selective enforcement have decreased since 1995, the number of fines in the year 2001 was still substantial, and the broadcast media is often left wondering exactly where their boundaries lie.

Education and Training

As yet, major associations and organizations within BiH are still not developed, although the international community has stepped forward to assist in training, developing media policy and even in financing struggling papers.

Although several international media groups are trying to establish a journalism training program in Sarajevo, very little training is available, and media professionals by and large are unaware of the country's new media laws and how they impact their rights and ability to work. The journalism outlets that currently exist have largely been tainted by years of corruption and government censorship and financial control. Many talented journalists left Bosnia-Herzegovina during that period when they were restricted and forced to become part of the propaganda machine during the war. Still others were fired by their editors or publishers, when political parties threatened or pressured them to quiet dissenting or even fair-minded journalists. There are few experienced professional mentors with an understanding of a balanced press left to train young journalists in BiH.

Summary

Although the media in Bosnia-Herzegovina remains weak and generally poor, a few examples of progress have emerged, particularly since 1998 and the adoption of a few still-developing media laws.

Still, a few factors will continue to plague the media scene for several years. First are the poor management practices in the media. During a period of consolidation of the media, few publishers are prepared. They lack business skills and financial resources to survive, and the financial infrastructure is not equipped to support them.

Another factor is the aftermath of the war, and how the country suffered as it remained in survival mode for most of the 1990s. There is a serious lack of educated and talented journalists in the country, and most young journalists learned their trade during the war years, and are not prepared to write objective news. They are still eager to be spoon-fed their information from official outlets, which are often not above spinning stories to the point of being untruthful.

Further, the country is technologically disadvantaged. Many media have not the resources to purchase and maintain advanced computer hardware and software, and few journalists are trained to use the technology available to them.

Although a variety of media are available, Bosnians have few choices in independent and fair media outlets. Broadcast media in particular are still heavily dominated by the government and its influence, and Bosnians are bombarded with slanted and narrow views in the media.

Significant Dates

- October 1999: The Nezavisne Novine editor-in-chief lost both legs in a car bomb. Later the following year, he was threatened numerous times by unknown people. In June, 2000, authorities arrested six people for attempted blackmail, but although they were also suspects in the acts against the editor, police were not able to charge them with the bombing.

- October 1999: Oslobodjenje is forced to reduce its staff from 250 to 160, in the wake of poor economic conditions. Prior to the war, the paper was the largest daily in Bosnia, selling 60,000 copies daily. In 1999, circulation dropped to about 14,000.

- April 2000: A Dnevni Avaz journalist is assaulted by the driver of Federation Prime Minister Edhem Bicakcic after the journalist wrote articles criticizing Bicakcic.

- June 2000: Edin Avdic, a journalist from the weekly Slobodna Bosna , was assaulted outside his home after receiving threats from the Chief of Cultural Affairs. The victim claimed the Chief, Muhamed Korda, demanded he stop writing articles about the cultural activities of the government, and had threatened to kill him if he would not stop.

- June 2000: Tax authorities raided, without explanation or court order, the daily Dnevni Avaz . Distribution of the paper was delayed and the authority billed the paper $450,000 for 1998 unpaid taxes. The raid came after the newspaper's split from partisan reporting in favor of the nationalist SDA (the Party of Democratic Action) party, and adopted a more neutral and fair reporting style. Prior to the raid, the paper had been threatened. The paper's editor in chief said the reason for the raid and the audit was a series of stories and editorials about corruption, implicating SDA leadership.

- August 2000: A journalist from the Ljubisa Lazic was assaulted after a series of threats and harassment by Marko Asanin, president of the regional board of the Srpsko Sarajevo Independent Party of Social Democrats. Asanin had previously attempted to exclude local media from assembly sessions.

- May 2001: Daily paper, Oslobodjenje , stopped publishing for the first time in nearly 60 years. The closure was due to an employee strike. The paper resumed printing one week later, and the labor dispute was resolved. Among employee complaints were late paychecks, and 20-percent pay cuts. Employees argued they had tolerated the financial instability during the war, but some five years later, were still waiting to be compensated fairly.

Bibliography

Aumente, Jerome. "Profile in Courage," Committee to Protect Journalists, CPJ Online. 15 December 1999. Available from http://www.cpj.org .

"Bosnia and Herzegovina Media Analysis," IREXProMedia. April 2000.

"Bosnia 2001 World Press Freedom Review," 2002. Available from http://www.freemedia.at/wpfr/bosnia.htm .

Gjelten, Tom. Sarajevo Daily: A City and its Newspaper Under Seige. New York: Harper Collins Publishers Inc., 1995.

Glenny, Marsha. The Fall of Yugoslavia. New York: Penguin Books, 1992.

Helsinki Committee for Human Rights, "Bosnia and Herzegovina—Republika Srpska: Freedom of expression and access to information." November 1999.

Howard, Ross. "Mediate the Conflict," Radio Netherlands. 22 March 2002.

Ivanova, Tanja. "Sarajevo: Newspapers in the Wringer," AIM Press. 25 Oct. 2001. Available from http://www.aimpress.org .

Perenti, Michael. To Kill a Nation. New York: Verso, 2000.

"U.S. Department of State Report: Bosnia and Herzegovina," 23 Feb. 2001. Available from http://www.state.gov .

Vincent, Isabel. "International media under attack in Serbia," National Post. 23 November 1998.

Carol Marshall

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: