Bolivia

Basic Data

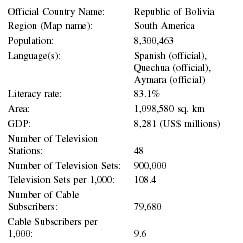

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Bolivia |

| Region (Map name): | South America |

| Population: | 8,300,463 |

| Language(s): | Spanish (official), Quechua (official), Aymara (official) |

| Literacy rate: | 83.1% |

| Area: | 1,098,580 sq. km |

| GDP: | 8,281 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Television Stations: | 48 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 900,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 108.4 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 79,680 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 9.6 |

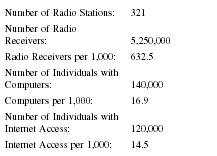

| Number of Radio Stations: | 321 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 5,250,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 632.5 |

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 140,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 16.9 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 120,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 14.5 |

Background & General Characteristics

The only landlocked Andean country of South America, La República de Bolivia (The Republic of Bolivia) is bordered by Brazil, Peru, Chile, Argentina, and Paraguay. The country's population is approximately 8 million, about 40 percent of which live in rural areas. Bolivia has the unique claim to having two national capitals, La Paz (the seat of government) and Sucre (the seat of the judiciary). Other major cities include Santa Cruz, Cochabamba, and El Alto. The country is 425,000 square miles, about twice the size of Texas.

The people of Bolivia suffer from various economic and social problems. Two-thirds of the population live in poverty, one of the biggest issues facing the Bolivian government. The country's literacy rate is about 83 percent, one of the lowest in South America. There are three official languages in Bolivia: Spanish, Quechua, Aymara; about half of the population speaks Spanish as their first language. There is a huge wealth gap within the population, especially between wealthy city residents and poorer urban farmers and miners. Approximately 55 percent of the people are of indigenous descent (Quechua, Aymara, or Guarani), 30 percent are mestizo (mixed European-indigenous heritage), and 15 percent are white. The predominant religion is Catholic (95 percent), followed by various Protestant and non-Christian religions.

Like most of its neighbors, Bolivia's journalistic tradition began as an extension of Spanish colonial culture and rule. After it gained independence from Spain in 1825, Bolivia's newspapers continued to be official state publications of the new country. One of these newspapers was La Gaceta de Gobierno ( The Government Gazette ), established in 1841. Various political factors created and controlled other politically oriented newspapers throughout the 1800s, a characteristic known as caudillismo.

Today, Bolivia boasts 18 daily newspapers, most of which are published in La Paz, where the combined daily circulation is approximately 50,000 copies. Among the most distributed newspapers are El Diario, La Razon, and El Deber ( The Daily, The Reason, and The Duty, respectively). The country's overall circulation is not very high, averaging about 55 readers per 1,000 people. There are several reasons for the relatively low circulation, including distribution and infrastructure problems, a high poverty rate, and the high illiteracy rate.

The volatile political nature of Bolivia has made the journalism profession often dangerous, especially for reporters. Numerous incidents over the last few years have resulted in harm to various media professionals. In 2000 staff at La Presencia —a daily newspaper in La Paz— received death threats and a bomb scare after the paper investigated a major drug trafficking story in the country. A year later in 2001, reporter Juan Carlos Encinas was killed while covering a conflict between two companies fighting over a limestone cooperative. Then in 2002, journalists were placed at danger while covering protests after the government closed a coca place. Other similar events, some of which have involved the Bolivian military, have also been recorded.

Despite these dangers, the Bolivian media is responsive to its obligations to its readers. Different newspapers have participated in projects highlighting civic responsibility and freedom of information. In 1998, El Nuevo Dia ( The New Day ) published a two-page questionnaire, "Discover if you are part of the problem," which was intended to make people think about their social responsibility to fight corruption. This undertaking was part of a larger project to promote democracy in Bolivia.

Economic Framework

Bolivia is the poorest country in South America. Recovering from severe recession in the 1980s, it enjoyed moderate growth in the 1990s, until the economy slowed down after the Asian financial crisis in 1999. Periods of hyperinflation over the last two decades—which peaked at 24,000 percent—caused a generally unfavorable economic environment for the struggling media in the country and also created civil unrest, which exacerbated already-difficult working conditions for journalists. Foreign investment and the privatization of several key Bolivian companies resulted in investment capital for infrastructure improvements in the mid and late 1990s, but the only aspect of communication to benefit directly was the telecommunications industry (telephone and Internet). The primary business sectors in Bolivia are energy, agriculture, and minerals. Many of these resources, especially mining, have not been developed to their full potential.

The success of media in Bolivia is dependent not only on the general state of the economy itself, but also upon its relationships with political and private entities. Generally, media that are most visibly pro-government receive more business than those media who are openly critical. Media that criticize the government rely on small, often limited, private funding, a condition that promotes self-censorship. The La Paz newspaper, El Pulso ( The Pulse ), which is noted for its sometimes unfavorable reporting of political events, is owned mostly by journalists. Reporters may also find writing about corruption in the corporate sector difficult because of the close ties between media owners and businesses.

Press Laws

Historically, Bolivia has maintained laws designed to protect the rights of individuals, companies, and the media. One of the first pieces of legislation of this type was the Print Law of 1925, which guaranteed the confidentiality and legal protection of sources. In 2000, a legislative proposal to repeal this law was introduced, but was withdrawn following a march on the national capital by Bolivian journalists, who are called periodisticas. Periodisticas, like all Bolivian citizens, are guaranteed freedom of speech under Article 7 of the Constitution Politica del Estate de 1967 (Constitution of the States). Yet many legal parameters exist for journalists, such as the Electoral Code Reform Law of 2001, which gives the National Electoral Court the legal right to suspend media who do not follow carefully constructed rules for political advertising. Periodisticas can also invite sanctions from the government for reporting that is slanderous or too critical.

One of the biggest areas of Bolivian press law is related to defamation. Defamation is almost always treated as a civil violation; although, if it is directed at a public official, may carry criminal penalties. The Telecommunications Law of 1995 sets forth mandates requiring infringers to pay damages, and another law provides for 40-member juries (some members of which may actually be journalists) in each municipality to hear cases of defamation and award civil damages. A 1997 amendment to the Penal Code also strengthened copyright laws, making infringement a public crime, allowing police enforcement if necessary. Consequently, Bolivian journalists tend to exercise extreme self-regulation and caution when covering government corruption and politically sensitive topics.

According to Bolivian law, all journalists must have a university degree in journalism and register with the National Registry of Journalists in order to exercise their profession inside the country. Some exceptions can be made through official channels of the Ministry of Education for experienced journalists who lack an academic degree. People who call themselves journalists without complying with these legal requirements are sanctioned and can be criminally prosecuted. These laws are considered a violation of human rights by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights but are still in effect, although not necessarily enforced.

Censorship

The press in Bolivia plays an especially important civic role, serving as a primary means of challenging governmental corruption. Like many other South American countries, a free political process is still a relatively new concept; many countries in South America, including Bolivia, did not replace dictatorships with full-scale democracies until the middle part of the twentieth century. Thus, authoritarian traditions and attitudes are still widespread within these societies and still may impede the complete liberties of periodisticas.

There is currently concern in Bolivia that the press does not enjoy complete freedom to investigate and report on politically sensitive issues such as government and corporate corruption. Although the Bolivian constitution guarantees free speech to all citizens, under the existing Penal Code, journalists—or any citizen, for that matter—who defame or insult public officials can be jailed. Greater sentences can even be imposed if the de-famed official is high-ranking, such as the president or a cabinet minister. Even implied defamation can carry consequences. For example, a special tribunal was called in La Paz in 1999 after the magazine Informe R published a photo of then-President Banzer with Augusto Pinochet, former authoritarian leader of Chile.

Other examples of censorship exist in recent Bolivian history. In 2000, after protests over a proposed water rate hike, the military took control of three radio stations in an effort to control coverage of the event. Also during that year, Ronald Mendéz was initially jailed on criminal defamation charges after he reported on alleged embezzlement by officials at a local water company. He was cleared before serving his sentence, however.

In 2001, senator and former government minister Walter Guiteras resigned office after being accused of intimidating media to suppress coverage of his alleged assault on his wife and for presumably bribing police officers to cover the incident. In a protest march from Cochabamba to La Paz, journalists were assaulted by police, and later that year Bolivian security forces allegedly fired at reporters in Chaparé. However, the journalists in both cases were present in conflict zones, and there was no evidence that the journalists themselves were the actual targets of police force.

State-Press Relations

The relationship between the Bolivian government and the press is tense. These tensions exist for a number of reasons, including the past violence as previously described, conflicting free expression laws in the Criminal Code, the country's stressful economic conditions, and more recent legislation controlling the media's coverage of political campaigns. Moreover, the Bolivian government reserves the right to withhold information about any topic, including those issues of public interest, which further restrains the press.

Attitude Toward Foreign Media

All media activity in Bolivia is subject to the rules of the Ministry of Government Information. Many foreign press organizations have bureaus in Bolivia, including the U.S.-based Associated Press. Most major developments in Bolivia are covered by a host of international journalists from organizations such as CNN and the British Broadcasting Corporation. Foreign journalists must be accredited through the Ministry of Education in order to work in the country.

Bolivia cooperates with the Comisíon Interamerica de Telecomunicaciónes (Inter-American Telecommunication Commission), an entity of the Organization of American States, which coordinates and develops telecommunications among governments and private sectors of countries throughout the western hemisphere. The country also participates in exchanges and fellowships with media professionals from other countries, such as David Boldt, a retired journalist from the Philadelphia Inquirer, who trained Bolivian journalists as part of a Knight Fellowship from 2001 to 2002.

News Agencies

Several main news agencies operate in Bolivia. The largest agency, La Agencia Boliviana de Información, is operated by the government under the Ministry of Government Information, and provides information for Virtualísimo, an online news site. La Agencia Nacional de Noticias Jatha, a widespread private news agency in existence since 1992, offers national news and business news. Other agencies include La Agencia de Noticias Fides, which is owned and operated by the Catholic Church, and Le Agence France-Presse Worldwide, a France-based agency, which maintains an office in La Paz.

Broadcast Media

Over the last decade, the broadcasting industry in Bolivia has matured, particularly in regards to the television market, which is the principal advertising media—as of 2002 there are over 900,000 television sets owned by Bolivia's 8 million people—followed by newspapers and radios, respectively. Several major television reds (net-works) exist, including the privately owned P.A.T. network and the state-owned Empresa Nacional de Televisíon Bolivania, which broadcasts on seven stations in different parts of the country.

Altogether, Bolivia has 48 television stations, 73 FM radio stations, and 171 AM radio stations. Eight television stations are operated by various universities; one radio station is state-owned.

Like the Federal Communications Commission in the United States, the Bolivian government also has an agency that regulates electronic media. All broadcast stations, cable systems, and Internet services are subject to the control of La Superintendencia de Telecomunicaciónes (SITTEL), whose office is administered under the Ministry of Economic Development. SITTEL's vision to ensure "more and better communications at less cost" also involves protecting the legal rights of businesses and consumers. In Bolivia, television piracy (receiving services without paying for them) is a serious problem, with a piracy rate of about 95 percent. The Dirección General de Televisión, an office under the auspices of SITTEL enforces the general regulation of television service, which includes penalties for illegal broadcasts.

Electronic News Media

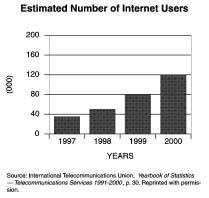

Despite a poor communication infrastructure and expensive telephone rates, Bolivia leads its South American neighbors in the area of online newspapers. At least 10 print newspapers in La Paz, Santa Cruz, and Cochabamba also maintain online sites. Various online services such as Bolnet, offer links to official news, education, business, and country events.

Education & TRAINING

Many of Bolivia's universities offer programs in telecommunications, journalism, and communication science. Students receive a licenciatura, the equivalent of a bachelor's degree, which qualifies them to register with the National Register of Journalists. Several universities operate local television stations that schedule cultural and public interest programming. One example is La Televisión Universitaria, which has been in operation at the Universidad Autonómia Juan Misael Saracho in Tarija for 25 years. Although under the auspices of the SITTEL, this station and other university-run media outlets are free to maintain their own programming without governmental influence.

Students with interests in print or electronic communication follow structured plan de estudios (programs of study) depending on their particular intended academic focus. Earning a licenciatura typically involves three to four years of full-time school, assuming a student takes five to six courses per semester. Some universities, such as la Universidad Católica Boliviana and la Universidad Mayor de San Andres, offer postgraduate and certificate programs in telecommunications and related areas.

Students studying journalism and broadcasting complete cursos especialidades (specialized courses), which are structured very similarly to academic programs found in the United States. Bolivian college students majoring in communication generally take the equivalent of general education courses, including mathematics, sociology or psychology, natural sciences, and political science, which are integrated with courses in their major field. Students receive licenciaturas with emphases in communication science, telecommunications, journalism, or other closely related fields. Specialized programs such as the Ingeneiería de Telecomunicaciónes (telecommunications engineering) at the Catholic University of Bolivia include courses in satellite and digital technology, as well as other technical aspects of mass communication.

In addition to courses in writing, editing, communication law, ethics, and technology, a Bolivian journalist's academic training may also include courses related to religion, culture, philosophy, or behavioral studies. Credit may be received for courses based on lecture hours, laboratory work, or special workshops.

Summary

Because Bolivia is a country that has not yet reached its economic and social potential, its press faces various political barriers. Rigid defamation laws and potential censorship by the government hinder reporters' effectiveness in bringing information to the public. Violence due to social unrest in the country represents a danger to journalists, who may be directly or indirectly harmed by civilians or police. In short, Bolivia has not fully embraced the freedom of expression guaranteed by its constitution.

Moreover, a low literacy rate and widespread poverty restrict the extent to which the populace consumes information, especially print material. The wide reach of television compensates for this limitation, especially for advertisers in the larger metropolitan areas, whereas newspaper circulation remains relatively low.

On a more positive note, although infrastructural problems still need to be solved, Bolivia has taken great strides in introducing technology into the press industry. Despite the comparatively small size of the country, both in area and population (its neighbors, particularly Brazil, are much larger in both respects), Bolivia is a leader in electronic media in South America. Its universities keep abreast of current technological innovations and provide students with a well-rounded liberal arts education.

As Bolivia continues to solve its internal problems, it will no doubt lead the region in state-of-the-art print and broadcast journals. Its abundance of natural resources and its strong cultural history will serve to enhance its potential as an information-rich nation.

Significant Dates

- 1994: Constitution is revised.

- 1995: Telecommunications Act is passed, establishing current defamation laws.

- 2001: Electoral Code Reform Law is passed; reporter Juan Carlos Encinas is killed while covering a conflict between two companies fighting over a limestone cooperative.

Bibliography

"AFP Worldwide." Agence France-Pressne, June 2002. Available from http://www.afp.com .

"Agencia Boliviana de Información." La Agencia Boliviana de Información, June 2002. Available from http://www.comunica.gov.bo/abi .

"Background Note: Bolivia." U.S. Department of State, April 2001. Available from http://www.state.gov .

"Bolivia." The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) World Factbook , June 2002. Available from http://www.cia.gov .

"Bolivia." The Committee to Protect Journalism, June 2002. Available from http://www.cpj.org .

"Bolivia." Inter-American Press Association, March 2002. Available from http://www.sipiapa.org .

"Bolivia." International Intellectual Property Alliance, June 2002. Available from http://www.iipa.com .

"Bolivia Country Commercial Guide." U.S. Commercial Service. Available from http://www.usatrade.gov .

"Bolivia: Marketing U.S. Products and Services." Tradeport, June 2002. Available from http://www.tradeport.org .

"Bolivia: Media." World Desk Reference, June 2002. Available from http://www.travel.dk.com .

"Bolivia: Media Outlets." International Journalists' Network, June 2002. Available from http://www.ijnet.org .

"Bolivia Newspapers." Onlinenewspapers.com , June 2002. Available from http://www.onlinenewspapers.com .

"Bolivia: Press Overview." International Journalists' Network, June 2002. Available from http://www.ijnet.org .

"Bolivia: World Press Freedom Review." International Press Institute, June 2002. Available from http://www.freemedia.at/wpfr/bolivia.htm .

"Bolnet." Available from http://useradmin.bolnet.bo .

"Country Profile: Bolivia." BBC News, March 2002. Available from http://www.news.bbc.co.uk .

"Diplomado en Gestión de Información y Documentación en las Organizaciones." Universidad Mayor de San Andrés, June 2002. Available from http://www.umsanet.edu.bo .

"Education." Bolivia Web, June, 2002. Available from http://www.boliviaweb.com .

"Golden Eagle Praised by Gold Mining Coop in Bolivia's Largest Circulation Newspaper." SocialFunds.com , 16 April 2002. Available from http://www.socialfunds.com .

"Inter-American Telecommunication Commission." CITEL, June 2002. Available from http://www.citel.oas.org .

"Knight Fellows to Train Journalists in Four Continents." International Journalists' Network, 2001. Available from http://www.ijnet.org .

"Latin America." The International Media and Democracy Project, June 2002. http://www.centralstate.edu .

"Licenciatura en Ciencias de La Comunicación Social." Universidad Católica Boliviana-La Paz, June 2000. Available from http://www.ucb.edu.bo .

Meyer, Eric K. "An Unexpectedly Wider Web for the World's Newspapers." Newslink, June 2002. Available from http://newslink.org .

"Misión—Visión." Superintendencia de Telecomunicaciones, June 2002. Available from http://www.sittel.gov.bo .

"Paseo por el Periodisma: A History of Journalism in Latin America and Spain." University of Connecticut Library, June 2002. Available from http://www.lib.uconn.edu/exhibits .

"Periodismo." Universidad Privada de Santa Cruz de la Sierra, June, 2002. http://www.upsa.edu.bo .

"Plan de Estudios," Universidad Católica Boliviana-Cochabamba/San Pablo, June 2002. Available from http://www.ucbcba.edu.bo .

"Plan Curricular de Ingeneiría de Telecomunicaciónes." Universidad Católica Boliviana-Cochabamba, June 2002. Available from http://www.ucbcba.edu .

"Press Freedom in Latin America's Andean Region." The International Women's Media Foundation, 2001. Available from http://www.iwmf.org .

"Press Laws Database." Inter-American Press Association, June 2002. Available from http://www.sipiapa.org .

"Quienés Somos," Bolivision, June 2002. Available from http://bolisiontv.com .

"Serivicios de Comunicación." Universidad Autónoma Juan Miseal Saracho, June 2002. Available from http://www.uajms.edu.bo .

"Telecomunicaciónes." La Universidad de Aquino Bolivia, June 2002. Available from http://www.udabol.edu .

could you please help me

thankyou