Burundi

Basic Data

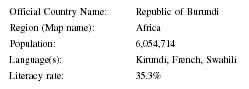

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Burundi |

| Region (Map name): | Africa |

| Population: | 6,054,714 |

| Language(s): | Kirundi, French, Swahili |

| Literacy rate: | 35.3% |

Background & General Characteristics

Burundi is a small parliamentary democracy in Central Africa, south of Rwanda, west of Tanzania, and east of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Lake Tanganyika forms Burundi's southwest border. The country's capital is Bujumbura. Over the past decade, Burundi's six million people have experienced some of the worst ethnic violence on the African continent. Since 1994 over 200,000 have been killed in ethnic conflict linked to the genocide that took place in neighboring Rwanda that year.

Burundi's two major ethnic groups are the Hutus (majority) and the Tutsis (minority). The imbalance of power among ethnic groups instigated through the manipulations of European imperialists in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries underlies the violence that continues to beset the region. The major language groups in Burundi are Kirundi and French, both of them official languages, and Swahili. Most Burundians are Christian (principally, Roman Catholic) or practice indigenous religions.

In 1993 Melchior Ndadaye, a political leader of Burundi's Hutus, who previously had been excluded from power, was elected president in Burundi's first democratic elections following independence from Belgium in the early 1960s. With Burundi's newly elected parliament, the National Assembly, led by the Hutu Front for Democracy in Burundi (Frodebu) party, Ndadaye became Burundi's first Hutu head of state in a country whose politics long had been dominated by Tutsis. However, a few months after his election, Ndadaye was assassinated, sparking renewed ethnic violence in Burundi that evolved into nearly a decade of civil war. Early in 1994 Burundi's Hutu-dominated parliament elected Cyprien Ntaryamira, another Hutu, as president. Unfortunately, President Ntaryamira's tenure as Burundi's head of state was very short, as he was killed—along with Rwanda's president—in a suspicious helicopter crash in April 1994, an event that sent neighboring Rwanda into a genocidal civil war of its own.

In October 1994 another Hutu was appointed president of Burundi, Sylvestre Ntibantunganya, following talks between the key parties in parliament. Just a few months later, however, the Union for National Progress (Uprona) party, a largely Tutsi party, already was withdrawing from the government and the parliament, and further ethnic violence erupted. Pierre Buyoya, a Tutsi, seized power in July 1996 and has remained president as of 2002. Buyoya first took power in Burundi in 1987 by overthrowing another Tutsi leader, but stepped down from the presidency in 1993 when Melchior Ndadaye was elected president.

In November 2001 a new power-sharing agreement was signed by President Buyoya, 17 political parties (10 Tutsi based, seven Hutu based), and the National Assembly in order to inaugurate a transitional government. However, the principal rebel groups refused to acknowledge or abide by this accord, and the fighting between rebel groups and government forces continued.

While the death toll in Rwanda exceeded that in Burundi many times over, the loss of life and levels of brutality and human suffering over the past decade in the two countries, as well as in neighboring DRC and in nearby Uganda and the Sudan, has been enormous. Ethnic violence continued in Burundi in early August 2002, and ongoing peace efforts had not yet produced a peace accord simultaneously agreeable to Buyoya's Tutsi-led government and the two main Hutu rebel groups: the Forces for the Defense of Democracy (FDD) and the National Liberation Forces (FNL).

Although peace talks to settle the conflicts plaguing Burundi have been frequent and mediated by such notable figures as former South African President Nelson Mandela and former Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere, no firm solution to problems of power sharing, continuing ethnic violence, and refugee return had yet been found by early August 2002, when new peace talks were slated to begin in Tanzania. As of mid-2002, some 600,000 to 800,000 Hutu civilians—about 12 percent of Burundi's population—were housed in "regroupment camps" in Burundi. The Tutsi-led government portrayed these persons as being held in the camps for their own protection against potential further ethnic violence by Tutsis seeking vengeance for earlier massacres of Tutsis at the hands of Hutu extremists—and also to prevent any Hutu rebels likely to attack Tutsis from hiding among other Hutus. Sadly, many of the internally displaced Hutus in Burundi were starving and/or dying of disease in the camps. The Tutsis who were forced from their homes in 1993 at the start of Burundi's civil war also have suffered greatly. They, too, remain housed in camps, unable as of mid-2002 to return to their homes. They are also dangerously vulnerable to diseases and to attacks from Hutu rebels, much as the Hutus in the regroupment camps are susceptible to attacks from the Tutsi-dominated government army. Another 400,000 Burundian refugees were said to be living in neighboring countries, according to an October 2001 report by the Committee for Refugees cited by the Committee to Protect Journalists. Many Burundian refugees, including members of one of the anti-government rebel factions still fighting the Burundian government, were housed in camps in Tanzania in mid-2002.

The media are strongly influenced if not outright controlled by the government. As the BBC Monitoring service notes, "The government runs the main radio station as well as the only newspaper that publishes regularly." The principal newspaper in the country is Le Renouveau, the government-owned paper. L'Avenir is another newspaper favorable to the government, as is La Nation, a private, pro-government paper. The Tutsi-based National Recovery Party publishes the private newspaper, La Vérité. The Catholic Church publishes its own newspaper, Ndongozi. The Hutu-backed Frodebu party published La Lumiére, the only opposition paper in the country until it, too, ceased publication in March 2001 after its publisher, Pancrace Cimpaye, left the country to go into exile. Cimpaye had begun receiving anonymous death threats after publishing lists of government military officers—most of them, Tutsis from Bururi province— identifying their home provinces and the shares they owned in parastatal companies.

Despite the challenges posed to the private media, independent forces are skillfully addressing problems inherent in the national reconstruction of an interethnic community and fostering peace and reconciliation. Studio Ijambo, based in Bujumbura, is part of one very successful effort at creating new types of programming to counteract the kind of "hate radio" promulgated in the early 1990s that contributed heavily to the genocide in Rwanda that overflowed into Burundi. Working in partnership with a Tanzanian radio station, Radio Kwizera, in mid-2002, Studio Ijambo aimed to build tolerance and understanding between Tutsis and Hutus by creating news and educational programs in Kirundi and French for broadcast on state and private radio stations in Burundi, over the Internet via www.studioijambo.org , and on a community radio station in the eastern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Outlining the goals of this positive initiative, the directors of Studio Ijambo and Radio Kwizera noted, "As the facilitated repatriation continues, there is a critical need for accurate, balanced and objective information on both sides of the Burundi border. The Studio Ijambo—Radio Kwizera collaboration aims to rise to this challenge, using the power of radio to reunite Burundian refugees with their compatriots in Burundi."

Economic Framework

Burundi is heavily dependent on agribusiness for its economy. Much of the economy is based on coffee, and tea, sugar, cotton, and hides are the other principal exports. Per capita annual income is only about US $110— one of the lowest incomes in the world.

The private press is significantly challenged by government attempts to control information viewed as potentially able to destabilize the country or to critique government policy or actions.

Press Laws

The Transitional Constitution Act does not limit press freedom. However, the government does limit freedom of speech and of the press. Additionally, according to a press law, a government censor must review newspaper articles four days before publication. "Newspapers are sometimes forced to close, then reappear again," according to BBC Monitoring.

Although Burundian law does not require owners of private news agencies to complete a registration of copyright, the director of Netpress, a privately owned news agency in the country, was arrested and charged in June 1999 with neglecting to complete such a registration. The editor of Netpress was arrested and detained for one week in December 2001 by government authorities, who also stopped Netpress from issuing news briefings during that same period. Eventually the charges against the editor were dropped, but only after his family paid a fine without his knowledge or consent.

Censorship

Journalists carefully practice self-censorship, but some room for the expression of a range of political views in the media does exist. The government also actively censors the media, harassing and detaining journalists at times and searching and seizing their property, such as cameras. This pertains especially to attempts by journalists to provide balanced coverage of the ongoing civil war.

State-Press Relations

Government-press relations are usually strained, if not outright conflictual, in Burundi except for media owned and operated by the government itself. The country's only newspaper able to publish without interruption is the government-owned paper, Le Renouveau, issued three times a week.

However, in April 2001 the government saw the benefits of having active, private radio stations when hard-line Tutsi soldiers naming themselves the Patriotic Youth Front overran the government's own station, Radio Burundi. The rebels had overtaken the government radio and begun announcing that Buyoya had been overthrown. The private media essentially came to the country's assistance by enabling government officials to use private radio stations to broadcast messages designed to reassure Burundians that a coup in fact had not occurred and to coordinate troop movements to stop the attempted coup. As the Committee to Protect Journalists observes, "The implications of the independent media's role in crushing the coup were not lost on Burundians, as President Buyoya praised private stations for offering a counterbalance to extremist opinions in the country."

Just one month earlier, however, according to the U.S. Department of State, Burundi's Minister of Communications in March 2001 "threatened to prosecute journalists and shut down news organizations that the Government believed were 'disseminating false information, divulging defense secrets, promoting the enemy, or promoting panic."'

In October 2001 government gendarmes arrested and beat a journalist, Alexis Sinduhije, who worked as a reporter for Radio Publique Africaine (RPA), a new private station employing both Hutu and Tutsi staff and advocating ethnic reconciliation. Sinduhije had met with visiting foreign military officers from South Africa, brought to Burundi secretly by the Burundian government in an attempt to address internal security problems associated with the repatriation of Hutus into the country. Sinduhije was fined and released the next day.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

The government tolerates broadcasting from foreign-backed and foreign media such as RPA, the BBC, the Voice of America, and Radio France Internationale. Burundians have been permitted to work as local reporters for these stations.

News Agencies

The government-controlled news agency is Agence Burundaise de Presse (ABP). The private news agency, Netpress, which operates in French and in English, has been sorely challenged by repressive government action, as already noted above. Another privately owned news agency, Azania, operates in French. Netpress and Azania have produced almost-daily newssheet faxes, projecting the political views of mainly Tutsi-based parties. Other electronic news agencies, such as Le Témoin, also are active in the country.

Broadcast Media

Because of the high levels of illiteracy and poverty in Burundi, radio is the most popular forum for the exchange of public views via the media. Few private broadcasting services exist in Burundi. The government runs the principal radio station, Radio Burundi, which broadcasts in several languages: Kirundi, Swahili, French, and English. Beginning in 1996 Radio Umwizero ("Hope") began broadcasting as a private station, funded by the European Union, with the aim of fostering peace and reconciliation in the country. That station later became Radio Bonesha, which met with difficulty in March 2001 when one of its journalists, Gabriel Nikundana, and its editor-in-chief, Abbas Mbazumutima, were arrested and fined after the station broadcast an interview with an FNL spokesman. Radio Public Africa, mentioned above, another independent station, began broadcasting in May 2001 in French, Kirundi, and Swahili.

Electronic News Media

Various Internet sites make news and perspectives on the reconciliation and peacebuilding process available to Burundians within and outside of Burundi. One example, already noted above, is Studio Ijambo, at http://www.studioijambo.org . Another is In-Burundi Diffusion and Communication, at http://www.in-burundi.net .

Summary

After nearly nine years of civil war, much of the Burundian population appears to be welcoming the return to a more stable political situation, although ongoing ethnic violence between the two main rebel, Hutu-based groups and the Tutsi-led government was still ongoing in mid-2002, even as close as a few miles from the capital, Bujumbura. While some doubted the long-term success of efforts to create a final peace accord and to keep the transitional government installed in November 2001 for the entire three-year period during which it was intended to serve, others appeared hopeful that a new climate of peacebuilding and reconciliation was possible.

The contributions of the private media have been no small part of this changing mood in the country, where any serious effort to secure lasting peace will necessarily have to involve people of all ethnic groups living in the country. By offering opportunities for Hutus and Tutsis to work together developing programming and broadcasting educational and news programs together aimed at fostering more positive outcomes for Burundi as a whole, media outlets such as Studio Ijambo and Radio Publique Africaine appeared poised in 2002 to make significant contributions to the future of the country.

The potential of Burundi's media, especially radio, either to foment war or to contribute to the establishing the conditions for peace was readily apparent to most Burundians, both within and outside the country. Along with the peace talks scheduled to take place in August 2002, the flourishing of private media oriented toward greater accuracy and more tolerance in reporting and interpreting events seemed to bode well for the prospect of transforming Burundi into a country where the political opposition could co-exist with the ruling party and all would have room for the free expression of their ideas.

Significant Dates

- July 1996: Pierre Buyoya seizes power and becomes president of Burundi.

- March 2001: La Lumiére, the only political opposition newspaper in the country published on a regular basis, ceases publication when its publisher, Pancrace Cimpaye, flees the country after receiving death threats.

- March 2001: Editor-in-chief and journalist of Radio Bonesha, a private radio station, are arrested and fined after broadcasting an interview with a rebel spokesman.

- April 18, 2001: Calling themselves the "Patriotic Youth Front," 30 hard-line Tutsi soldiers take over Radio Burundi, the government radio station, and announce Buyoya's overthrow, but are soon counteracted by government troops and broadcasters temporarily using private radio stations to assure Burundians that a coup in fact has not occurred and to coordinate government troops.

- November 2001: Transitional government installed, involving power-sharing among President Buyoya, 17 political parties (both Hutu and Tutsi), and members of the National Assembly (parliament), but without the support of the two main rebel groups, who continue their fight against the government.

- December 2001: Netpress, a private news agency, temporarily halts operations when its editor is arrested and fined by the government.

- August 2002: New peace talks scheduled, with rebel groups failing to fully participate.

Bibliography

Amnesty International. "Burundi." Amnesty International Report 2002. London: Amnesty International, May 28, 2002. Available at http://web.amnesty.org/web/ar2002.nsf/afr/burundi!Open .

BBC Monitoring. "Country profile: Burundi." Reading, UK: British Broadcasting Corporation, March 7, 2002. Available at http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/africa/country_profiles/1068873.stm .

BBC News. "Truce call ahead of Burundi talks." August 5, 2002. Available at http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/africa/2173091.stm .

Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, U.S. Department of State. "Burundi." Country Reports on Human Rights Practices 2001. Washington, DC: Bureau of Public Affairs, U.S. Department of State, March 4, 2002. Available at http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/hrrpt/2001/af/8280.htm .

Committee to Protect Journalists. "Burundi." Attacks on the Press in 2001: Africa 2001. New York, NY: CPJ, 2002. Available at http://www.cpj.org/attacks01/africa01/burundi.html .

In-Burundi Diffusion & Communication. " Communiqué [Press Release]: Studio Ijambo." June 13, 2002. Available at http://www.in-burundi.net/Contenus/Rubriques/Lejournal/06_13ijambo.htm .

newafrica.com . "Thousands flee Burundi capital as rebels attack military positions." June 5, 2002. Available at http://www.newafrica.com/news/ .

Reporters without Borders. "Burundi." Africa annual report 2002. Paris, France: Reporters sans frontiers, April 20, 2002. Available at http://www.rsf.org/article.php3?id_article=1724 .

Barbara A. Lakeberg-Dridi , Ph.D.

From South Africa, pretoria-Apollo Painter, a singer.