Chile

Basic Data

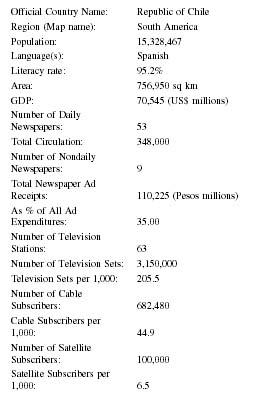

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Chile |

| Region (Map name): | South America |

| Population: | 15,328,467 |

| Language(s): | Spanish |

| Literacy rate: | 95.2% |

| Area: | 756,950 sq km |

| GDP: | 70,545 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Daily Newspapers: | 53 |

| Total Circulation: | 348,000 |

| Number of Nondaily Newspapers: | 9 |

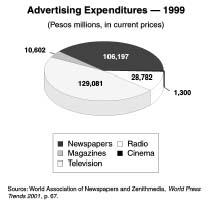

| Total Newspaper Ad Receipts: | 110,225 (Pesos millions) |

| As % of All Ad Expenditures: | 35.00 |

| Number of Television Stations: | 63 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 3,150,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 205.5 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 682,480 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 44.9 |

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 100,000 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 6.5 |

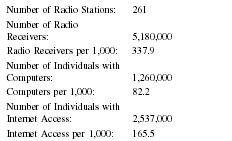

| Number of Radio Stations: | 261 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 5,180,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 337.9 |

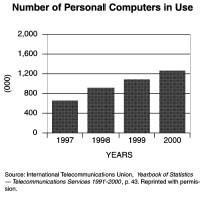

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 1,260,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 82.2 |

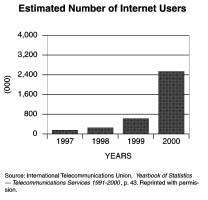

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 2,537,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 165.5 |

Background & General Characteristics

Before 1973, Chile was a model of political freedom among Latin American nations. The press was relatively free to publicly criticize government officials and their regimes. In 1970, Chilean citizens elected the Socialist politician Salvador Allende as national president. As of 2002, Chile remained the only country in the Americas to have democratically elected a Socialist president to power. From 1970 to 1973, the media flourished and freely reported on the political infighting, economic crises, and mass public demonstrations characteristic of President Allende's government.

However, on September 11, 1973, General Augusto Pinochet overthrew Allende's Socialist government and imposed a military regime. Pinochet ruled as president and dictator of Chile from 1973 until a freely elected president was installed in 1990. During his seventeen-year military dictatorship, Pinochet largely used the media to promote his newly imposed economic and anti-democratic policies. He also implemented state security measures that limited the civil rights of individuals as well as severely curtailed freedom of the press, expression of opinion, as well as flow and access to information.

In 1980, Pinochet wrote a new Chilean Constitution and implemented the Ley de Seguridad Interior del Estado (State Security Law), which was intended to control and maintain social order for the purposes of expanding the economy. He suppressed free speech and both print and broadcast media by enacting Article 6(b) in Chile's State Security Law. The Article declared it was illegal for anyone to publicly slander, libel, or offend the president of the Republic or any other high-level government, military, and police officials. The term, offense, was used to describe acts of disrespect or insult. Generally, the law gave discretionary power to supporters of the Pinochet regime to control the media and restrict free speech.

The provisions of the State Security Law also gave judges unrestricted power to place gag orders on alleged controversial issues and to ban press from court proceedings. Pinochet chose conservative pro-military individuals to support and enforce his policies. Pinochet also expanded the role of government censorship offices and widely increased the types of material that could be censored. In most cases, military members headed the censorship offices. People arrested for violating the provisions of the State Security Law were tried in a military court in which members of the military quickly reached guilty verdicts and imposed punishments. Defendants could be imprisoned for up to five years. These provisions radically curbed the print and broadcast media's freedom to report information without the threat of harassment or imprisonment.

Regulations permitting freer press and censorship laws gradually took place in the decade following the end of Pinochet's dictatorship. Although Pinochet left political office in 1990, he remained as chief commander of the armed forces until 1998 and as senator-for-life until his resignation in July 2002. The regulations in Article 6(b) and the 1980 Constitution that increased censorship and limited freedom of the press and information remained in effect until June 2001.

After 1990, the center-left parties, the Christian Democrats and Concertación Coalición (Concerted Action Coalition), had national power. The center-left presidents worked to pass freer press laws and repeal some of the repressive provisions of Pinochet's 1980 Constitution and State Security Law. The process to pass freer press and censorship laws took well over a decade. The slowness was in part due to the continued presence of Pinochet in the military as chief commander and in politics as senator and through his right-wing political party, the Independent Democratic Union. Moreover, the two right-wing parties in Congress, the National Renovation and Independent Democratic Union, supported Pinochet's policies of social order and regulating media.

In 1990, the first democratically elected president since 1970, Patricio Alywin, took office. During his presidential term, Alywin began the process of creating a freer and more democratic society, including liberalizing press laws to allow greater expression of opinion and flow of information. The "Law on Freedoms of Opinion and Information and the Practice of Journalism" was first proposed in 1993, though it was not passed until 2001 in part due to opposing forces in Congress.

In the late 1990s, President Eduardo Frei and his coalition, Concerted Action, led the struggle to pass more permissive censorship and opinion laws for the press and cinema. By 1997, the press operated far more freely than in 1990. However, Article 6(b) of the State Security Laws remained in effect and continued to limit journalists' rights to free speech. The regulations, for example, permitted judges to bar controversial topics and information from being freely expressed in the media. At times, judges imposed gag orders rather liberally and suppressed print and broadcast media from reporting freely.

In 2001, the "Law on Freedoms of Opinion and Information and the Practice of Journalism" passed in Congress and went into effect when President Ricardo Lagos signed it on May 18. The new press law repealed Article 6(b) and permitted the Chilean print and broadcast media to operate far more freely than it had been able to in thirty years. The law also repealed legislation that gave judges discretionary power to ban press coverage of court proceedings.

The "Law on Freedoms of Opinion and Information and the Practice of Journalism" passed in part because of events connected to Pinochet's arrest for human rights violations in London in October 1998. In Chile, these events led to the reawakening of bitter feelings over two decades of repression. In the late 1990s, Chilean citizens supported and voted through Congress provisions for free speech, freedom of expression, and access to information without persecution.

Chilean journalists were relieved with the repeal of Article 6(b). Nevertheless, some journalists believed that the press and information laws could go further to promote a truly independent press without government regulation.

Print Media

Most press activity occurs in the populous central valley of Chile, particularly in Chile's largest city, the capital Santiago. In 1996, Chile had 52 newspapers and newsprint consumption was 5,326 kilograms per one thousand inhabitants. However, in 2002, the number of published dailies had decreased to approximately 40 newspapers. This decline in dailies was in part due to the Chilean recession that began in 1999. Many small-scale publishers were bankrupted as it was difficult to maintain circulation and advertising revenue during the recession.

In 2002, the dailies ranged from nationally distributed and high quality newspapers to small-town tabloids. These newspapers were distributed between four and seven times per week. Distribution ranged from as much as 300,000 copies for El Mercurio (in its Sunday edition) to 3,000 copies of a regional paper. Chile's capital, Santiago, has nine major newspapers with a combined daily circulation of approximately 479,000. The circulation of local dailies in the regions outside Santiago was approximately 220,000. Assuming an average readership of three persons per newspaper, total readership countrywide could be estimated at more than 2 million readers per day.

Nearly all towns with populations of 50 thousand or more had newspapers that focused on local news and events. Apart from the publications of Chile's two newspaper chains, there were approximately 25 other independent regional dailies. These had a small circulation within their towns. One of the most important regional dailies was Concepción's El Sur , with a circulation of approximately 30 thousand.

Other important and widely read periodicals were the nondailies that appeared two to four times per month and were published for a nation-wide readership. The biweekly newsmagazine, Ercilla had an approximate circulation of 12 thousand. Other nondailies with relatively large circulations were the three business-oriented monthly magazines, America Economía , Capital , and Gestión . The two popular magazines, Cosas and Caras were biweeklies with Life magazine format. They published interviews with popular stars and athletes, as well as political interviews of national and international interest. Other widely-read publications in Chile included the following weekly and monthly magazines: El Siglo , the Communist Party's official weekly publication; Punto Final, a biweekly publication of the extreme-left group Movimiento de Izquierda Revolucionario (Revolutionary Left Movement); Paula , a women's magazine; Mensaje , an intellectual monthly magazine published by the Jesuits; and several sports and TV/motion picture magazines. Circulation information was not available for these non-dailies.

In 2001, two newspaper chains operated in Chile. Each chain was responsible for publishing the two most widely read newspapers, El Mercurio and La Tercera .

The first chain, the El Mercurio -chain, was owned by the Edwards family since the nineteenth century. It published and was affiliated with 15 dailies circulating throughout Chile. As of the early 2000s, El Mercurio , was Chile's longest-running and most influential paper. The El Mercurio-chain also published two other widely read dailies, the mass-oriented, Las Últimas Noticias and El Mercurio's afternoon supplement, La Segunda . According the official statistics by the United States Department of State, the daily El Mercurio attracted conservative audiences.

The second media chain was Consorcio Periodístico de Chile (COPESA), owned by Alvaro Saieh, Alberto Kasis, and Carlos Abumohor. COPESA published the news daily La Tercera for national distribution. La Terc era was a Santiago-based national newspaper with a 2002 daily circulation of about 210,000. As of that year, this number was the highest daily readership in Chile. El Mercurio competed with COPESA's La Tercera for newspaper readers. COPESA also published three other periodicals for national distribution: the popular magazine, La Cuarta ; the free daily tabloid, La Hora ; and the newsweekly, Qué Pasa , which offered political analyses of current events. In 2002, Qué Pasa had an approximate circulation of 20 thousand readers. COPESA created sites on the Internet for its publications. The publisher also had affiliations with smaller-scale print and digital publishers. One such affiliation was with the digital company that produced "RadioZero," a music Internet site for younger audiences.

The Nature of the Audience

In the early 2000s, the Chilean newspaper audience was in general well educated. School attendance was obligatory for children under the age of 16. The Chilean Ministry of Education made it obligatory that all children in the school system complete the eight-level system, ideally within eight years. Most children go beyond the eight years of elementary learning to attend secondary schools and university. In 1995, of those age 15 and over, some 95.2 percent of the total population was literate. Generally, high levels of literacy indicate a high number of potential readers.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, most publishing and other media activity were concentrated in central Chile, particularly in the capital of Santiago. Nearly 90 percent of the population was concentrated in central Chile, in the area between Coquimbo in the north and Puerto Montt in the south. Chile was not a densely populated country. Even in the central area, with the exception of the Santiago metropolitan area, the average population density did not exceed 50 inhabitants per square kilometer (130 per square mile). The average population density for the country was 17 persons per square kilometer.

In 1995, some 86 percent of the total population lived in urban centers and 41 percent of the total population lived in urban agglomerations of one million or more. For the press, it is advantageous to have markets concentrated in urban centers so as to obtain easy access to larger numbers of readers. As of July 2001, the population of Chile was estimated at 15,328,467 and population growth rate was 1.13 percent.

In the late 1980s, Chile's prosperity—due to Pinochet's aggressive free-market and trade policies—led to an increase in immigration. Migrants came from as close as neighboring Argentina and Peru and from as far away as India and South Korea to work as shopkeepers, doctors, musicians, and laborers. Many stayed on illegally after entering with tourist visas. In the 1990s, over 3 thousand Koreans legally registered as immigrants. Most set up small shops in which to sell textiles or imports from South Korea. In 1996, there were 814 legal Cubans, mostly working as musicians. The Cuban community estimated that as many as 6 thousand Cubans might be working illegally in Chile. Generally, immigrants assimilated into Chilean culture. However, there were imports of foreign dailies particularly from the United States, Asia, and European Union countries. The growing Cuban community also had small local publications that listed events and local news.

Chile's official language is Spanish. The two main ethnic groups are white and mestizo, which composed in 2002 some 95 percent of the population. Mestizo is a mix of European and Native American peoples. The Native American population composed 3 percent of the population. Some of the indigenous populations still used native languages, mainly the Araucanian language. Indian groups were largely concentrated in the Andes in northern Chile, in some valleys of south-central Chile, and along the southern coast.

In the early 2000s, the typical Chilean was not affluent. According to a report by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, in 1998, about 22 percent of the total Chilean population were below the poverty line. In 2000, the unemployment rate was 9 percent. The underemployment rate was estimated at nearly 20 percent. There were wide discrepancies between the poor and rich, which is a common characteristic among countries that impose fast-paced privatization and market-oriented policies. Pinochet's policies, for example, included tax relief for business and international investors, new marketing strategies, and massive trade expansion with foreign countries. His policies eliminated previous full-time jobs in state-run industries. He failed to create new jobs or train these former employees for existing higher-skilled jobs or for the new computer-technology occupations in the late 1980s. The new market system created few jobs for low skilled, state workers, which in part explains the high levels of under-and unemployment.

In 1998, the poorest 10 percent of Chilean households received only 1.2 percent of the national income, while those in the richest tenth possessed 41.3 percent of national wealth. Furthermore, in the bottom 10 percent, the proportion earning less than the minimum wage grew from 48 to 67 percent, indicating a serious deterioration of the conditions of the working poor.

In Chile, the most extensive mass medium was radio and not newspapers. For the most part, Chilean radio was a relatively inexpensive form of obtaining daily news. Nearly all homes had radios, so these constituted the prime source of current news to millions of Chileans.

Quality of Journalism: General Comments

Although some newspapers and nondailies reported tabloid news, employed bold headlines, numerous photographs, and techniques of strong popular and entertainment appeal, locally produced news were generally of high quality and drew large audiences through radio and readership. Laws current in 2002 required that all journalists obtain a university education and be professionally trained at a recognized journalism school. In most cases, professional journalists had sufficient training and developed a sense of duty for providing readers with accurate and important news pieces.

Historical Traditions

Chile was established and colonized by Spanish conquistadors in the 1540s. It developed as an isolated frontier with low levels of Spanish immigration and relatively large numbers of Indian groups in the northern Andes region and southern part of the country. In the early nineteenth century, Chile came into being as a nation-state when it joined in the independence wars against Spain. It declared independence from Spain on September 18, 1810.

Before 1810, all printed matter (newspapers, magazines, and books) had been published in Spain or in other European countries and brought through the ports of the Viceroyalties of Peru (ca. 1526) or Buenos Aires (1776). After the independence and civil wars in 1823, Chile began establishing its economy, politics, and press systems. Supreme Director, General Ramón Freire encouraged the flourishing tradition of free and polemical journalism. Between 1823 and 1830, over a hundred newspapers (many were short-lived) were printed. The country's first formal paper, El Mercurio , was founded in Valparaíso in 1827. It circulated daily beginning in 1829.

By the 1840s, Santiago was growing as a lively urban center. An important feature of urban life was the growth of the press. El Mercurio was by then the most prestigious paper in the country. From Valparaíso, the publishers of El Mercurio printed special Santiago editions and sent, via steamship, supplements of the paper along the coast and up to Panama.

The Chilean government subsidized a few papers in the mid-1800s to promote readership and spread news information. The government quickly discovered the benefit of using the press to promote policies and current leaders. By 1842, Santiago began publishing its first daily; unfortunately, it was short-lived. In 1855, El Ferrocarríl (The Railroad) became Santiago's most distinguished newspaper; it ran until 1911. The decade of the 1860s saw further good quality dailies like El Independiente (1864-91) and La República (1866-78). El Independiente represented the interests of the Conservative Party and La República , those of the Chilean Liberal Party.

The Spanish conquistadors introduced Roman Catholicism in the 1540s. All indigenous populations were christened en masse and called Christians when the Spaniards arrived and settled. From the colonial to twenty-first centuries, the Roman Catholic Church continued as the dominant religion in Chile. The Church began publication of its weekly magazine, Revista Católica , in 1843. This magazine continued its publication as of 2002. Re-vista Caólica was Chile's longest-running magazine.

By the early 1900s, the government promoted literacy and education through mass public campaigns in the cities and countryside. The results were greater literacy and schooling among the general population. Also, journalism gained new prominence as a profession. The higher literacy rates and increased number of full-time, professional journalists led to the growth of the press, in particular the provincial press flourished. Nearly every town published at least one newspaper reflecting on religious or political bias.

By the 1920s, dailies published in the urban areas diversified and expanded their topics to attract a greater number of readers. Santiago's most popular local paper was Zig-Zag , which was owned by the Edwards Family ( El Mercurio -chain). There was also a rise in papers published for specific clientele, such as those that catered to socialists, anarchists, workers, or a political party.

By the mid-twentieth century, Chile was gaining reputation as a place of diverse publications. Chile had printed more than 4 million books (1,400 separate titles) and published a variety of magazines (political, humorous, sports, feminine, right-wing, left-wing, Catholic, Masonic) and newspapers (including tabloids). Chile's largest newspaper, El Mercurio , had a daily circulation of 75 thousand readers.

Before September 1973, Chile's press was thriving and considered an important component of its democratic society. The press was very diverse and represented all levels of the political spectrum from ultra-right to ultra-left. Broadcast media also operated relatively freely and without fear of political repression. The press was relatively independent and investigative journalists operated without excessive regulation and certainly without threat of persecution. Politics were polarized ideologically and heated debates among politicians were commonplace. The press freely reported on all ideological polarization, political debates, and scandals.

Nonetheless, on September 11, 1973, General Pinochet led a coup and established an authoritarian government wherein little or no meaningful political competition or media freedom existed. In the 1970s and 1980s, the military government heavily regulated news media through regulation and the government censorship office. Pinochet passed press laws that restricted newspapers and magazines from making political commentary that could be termed libel, slander, or offensive. It was illegal and punishable by imprisonment for reporters to publish what could be considered negative or controversial reports on the leaders of the regime.

Pinochet used both broadcast and printed media to push his economic and social order policies. For example, he used the media to downplay or justify the repression that ensued after 1973. Although Pinochet stepped down from power in 1989, the laws restricting freedom of the press were in effect until June 2001.

In 2001, President Ricardo Lagos signed into effect the new press laws permitting journalists more freedoms including the right to criticize political leaders and their policies. Since 2001, journalists and legal advocates of free speech have actively ensured that their rights to free speech and access to information are never infringed upon again.

One of the most important conditions of the new press laws of 2001 was that reporters could once again question and criticize the decisions of government authorities. For example, on June 13, 2002, President Lagos announced that only two media sources would be allowed access on his international and domestic trips. Lagos's decision immediately provoked criticism from members of the press corp. The director of the National Press Association, a union of over 80 publications, deemed the announcement "unacceptable." The director said that Lagos was inhibiting the freedom of the press and the people's access to the news. The School of Journalists also criticized Lagos' decision. Due in part to pressure from distinguished journalists, Lagos responded and explained his actions in detail. His doing so was significant because in this case the press showed that it would question and criticize unjust policies. These events also indicated that journalists could expect responses from the president without the fear or threat of persecution.

Distribution by Language, Ethnic and Religious Orientation, Political Ideology

Most dailies were printed in Spanish, but there were a few foreign language dailies. In 2002, Condor was the German-language newspaper. A century earlier, the largest numbers of immigrants to Chile had been Germans, who colonized southern Chile. Germans had a larger impact in the colder regions of several southern Chilean cities. There were also several English-language economic and financial newspapers published in the metropolitan center of Santiago. These were The News Review , published twice a week, and the daily Santiago Times . These two publications also had Internet sites. On its Internet site, the Santiago Times provided free access to its daily headline only.

The majority of the population practices the Roman Catholicism. Approximately 89 percent of the population is Roman Catholic and 11 percent are Protestant. One of the longest running magazines in Chilean history, Revista Católica , has circulated since the nineteenth century. Mensaje , an intellectual monthly magazine published by the Jesuits, had a nation-wide readership. During the military dictatorship, Pinochet increased the role of the Catholic Church. He established a strong public relationship with Cardinal Francisco Javier Errazuriz, who also delivered Pinochet's resignation letter of his senator-for life post. Pinochet's public relationship with the Church was perhaps intended to divert attention from accusations of human rights violations during his dictatorship.

Since independence (except during years of military dictatorship), Chilean press reflected a strong political orientation and represented the political interests of the conservatives, liberals, ultra-rights, and ultra-lefts. In the nineteenth century, El Independiente represented the interests of the conservative party and La Republica , of the Chilean Liberal Party.

By 2002, nearly all political parties had their own Internet site. They also published pamphlets and small-scale periodicals to promote their political ideologies, strategies, and candidates. Most politically active groups regularly used the mainstream media to promote their policies and ideologies. Some of these political groups and their publications are: the Communist Party (legalized in Chile in 1990) which published El Siglo on a weekly basis; and the ultra-left group, Movimiento de Izquierda Revolucionario (Revolutionary Left Movement), which published the bi-weekly Punto Final . The center-left group, the Concertación (Concerted Action) a coalition of Socialists, Communists, and some factions of the Christian Democratic Party, was in power in 2002 and led by President Ricardo Lagos. Each faction within the coalition printed a weekly publication. The two right-wing/pro-military parties, Independent Democratic Union and National Renovation, also distributed propaganda.

Papers, particularly the two leading dailies La Tercera and El Mercurio were professional and well organized. These two top dailies had sections for news, commentary, editors' letters, sports, finance, business, economy, politics, as well as for cultural events and reviews. The most up-to-date news came from their Internet sites. They updated their headlines every 30 to 60 minutes during business hours.

The most prestigious daily, El Mercurio , has both a morning and an evening edition. Its largest sales came from the Sunday edition with a distribution in 2002 of 300,000 copies. El Mercurio was considered the right-wing/conservative paper for middle-aged and up audiences. La Tercera seemed to appeal to popular and younger audiences.

Economic Framework

After the independence wars in the nineteenth century, Chile became one of the wealthiest and most politically stable of the South American countries. The country sold produce and other raw materials to areas in and bordering the Pacific Ocean, such as California, Australia, and Panama. It even shipped its newspaper to audiences in Panama. Beginning in the early twentieth century, it mined its territories on the Andes and in the mountains of northern Chile for minerals such as zinc, tin, and most importantly, copper.

In the early twentieth century, copper became Chile's primary export product. The economy came, in fact, to be heavily dependent on international copper revenues. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Chilean government nationalized copper companies and implemented Socialist reforms so that the government owned the means of production. This action created greater economic inefficiencies as the public sphere was not as effective in market policies as private businesses. In the early 1970s, the government of President Allende also implemented expensive social reforms to aid workers and the urban poor. Despite the great expense, some left-wing political groups believed the government should spend more on social services while conservative groups wanted to severely pull back on them. In the end, these policies were shortsighted, and President Allende could not control the economic inefficiencies, mass political demonstrations, and urban terrorist attacks.

After September 1973, one major feature of the Pinochet regime was the immediate reversal of the previous leaders' Socialist-type policies. Between 1973 and 1988, Pinochet implemented free market reforms. During the early 1990s, Chile was a model for economic reform. Its free market policies welcomed international corporations to operate in Chile and it diversified its export products, which in part reduced its dependence on copper exports. In the 1990s, Chile's natural resources for export were copper, timber, iron ore, nitrates, precious metals, molybdenum, and hydropower. It also exported fruits, nuts, and other food resources. In 1994, five percent of Chile's land was used for crops and 18 percent was designated as permanent pasture.

In 1990, the elected government of President Patricio Alywin expanded the economic reforms that had been originally initiated by the military in the late 1970s. A high level of foreign trade and substantial foreign investment characterized the Chilean economy. In 2002, Chile belonged to several trading partnerships such as Mercosur, the South American free trade agreement. It adopted free trade negotiations with the United States through the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). It also belonged to the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), a trade and business collaboration with countries in Asia and those bordering the Pacific Ocean.

Growth in real gross domestic product (GDP) averaged 8 percent between 1991 and 1997. At the climax of

In 2002, Chile's economy was in a slight recession, although the country was faring far better than its South American neighbors were. The country was in part affected by the disastrous recessions in Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay. In Chile, unemployment remained high, and there was substantial pressure on President Lagos to improve living standards through social reform and job programs. One effect of the economic recession was a decline in newspapers from 52 in 1996 to 40 in 2002. Small-scale publications had the most difficulty in maintaining readership. This economic recession was anticipated to continue due to the region's financial calamity.

Press Laws

From 1973 to 1980, Chile was under rule of a military government. Pinochet ruled by emergency decree and suspended civil rights such as free speech, freedom of expression, and access to and flow of information. In 1980, Pinochet wrote new laws and a new constitution.

The most damaging provision against a free and independent press was Article 6(b) of the Ley de Seguridad Interior del Estado (State Security Law), which remained in effect until it was repealed in June 2001. Article 6(b) declared that it was a crime against public order to "libel, offend, or slander the president of the Republic, ministers of the state, senators or representatives, members of superior courts of law, the attorney-general of the Republic, the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, or the director-general of the carabineros ." (World Press Freedom Review). The carabineros were the modern police force of Chile that was created in the mid-1920s to provide better-trained and professional crime force teams.

In spring 2001, a new press law was passed in Congress and President Lagos signed the "Law on Freedoms of Opinion and Information and the Practice of Journalism" on May 18. The Law was enacted on June 4, 2001. The Law was first proposed in 1993 but was hampered by delays in Congress. The new press law intends to eliminate restrictions on press freedom that were originally approved under the Pinochet dictatorship.

Journalists and press freedom groups welcomed the repeal of several provisions of the country's infamous State Security Law including Article 6(b). Under the new press law, civilian courts, not military courts, hear defamation cases brought against civilians. The law also repealed legislation that gave judges discretionary power to ban press coverage of court proceedings.

Nevertheless, there were three points of the law that concerned Chilean journalists and legal advocates of free speech. First, the law declared that the official title or nomenclature "journalist" is limited to those who have completed university education from a recognized school of journalism. Any non-trained person who freely investigates and writes on any subject whatsoever cannot legally expect to be sheltered from laws protecting journalists' right to free speech, freedom of expression, and access to information. Second, the law restricted journalists' rights to protect sources. Only recognized journalists had this right. Recent journalism graduates, publishers, editors, and foreign correspondents could potentially have difficulty in being able to legally protect their sources. Last, desacato (insult) provisions of libel and slander were still considered criminal offenses.

Legal advocates of free speech criticized the current bill as a violation of international standards. They noted that it maintained "disrespect" as an offense under the penal code and imposed higher penalties for a defamation offense committed against a high official. Legal experts also objected that publications could still be banned under the new law.

Despite these three concerns, the new law did enable formerly exiled journalists to return to Chile. These journalists had faced charges for violating Article 6(b) of the State Security Law. They would have most likely been convicted in a military court and imprisoned for up to the five years under the old laws. The most notable journalist to return from exile, investigative journalist, Alejandra Matus Acuña, returned to Chile on 14 July 2001 after living in the United States for more than two years.

On 14 April 1999, police raided Acuña's publisher, Planeta, and confiscated the entire stock of her book, El Libro Negro de la Justicia Chilena (The Black Book of Chilean Justice). The book criticized and exposed the Chilean judicial system's abuse of power during the Pinochet dictatorship. Alejandra Matus Acuña fled to Argentina and was granted political asylum in the United States in September 1999.

The Alejandra Matus Acuña case generated an enormous public outcry from all sectors of Chilean society. Legislators demonstrated in front of the Supreme Court and carried "a huge pair of cardboard scissors, symbolizing the cutoff of information." ("Chile," World Press Freedom Review , 2001). Genaro Arriagada, Chile's ambassador to the United States, described the state security law as "absurd and unethical," adding that it "damages the image of our country" (World Press Freedom Review).

Another significant attribute of Chile's new press law was that other South American countries followed suit and recognized the importance of free speech and protecting independent journalism. In 2002, Chilean journalists found support for their struggle through journalist organizations throughout the Southern Cone (Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, and Paraguay). For example, Argentine journalists formed La Asociación para la Defensa del Periodismo Independiente (Association for the Defense of Independent Journalism). Although Argentine journalists headed the organization, their goal was to support freedom and report on repression and threats against journalists throughout the Southern Cone, particularly Chile. This group was created in December 1995 due to the onslaught of threats against the independent press and journalism in the 1990s. It was a non-government organization and independent of workers' unions or other organizations. Its members were journalists, editors, columnists, and writers in press and electronic media. Its goal was to promote pluralism and push forward policies toward greater freedom of expression.

Censorship

During the military regime, authorities could ban publication entirely and request Chilean publishers to submit their copies to the offices of censorship before publication. The censors had unrestricted power to suppress stories that could have been construed as harmful to public leaders. In 1997, the censorship laws written by Pinochet were still in effect and had a wide definition for constituting material that could be censored. For example, comedy programs that made jokes about Chile's national anthem or flag were threatened with being banned. These censorship laws permitted judges to place gag orders on controversial stories.

Nevertheless, the 1980 censorship laws targeted traditional forms of media such as broadcast and printed media. By 1997, the censorship laws did not cover newer forms of media such as CD-ROMs and the World Wide Web. For example, in 1997, the newspaper publishers of La Tercera opened an Internet site that gave the stories it would have published on its front page if a judge had not barred the print medium. In 2002, the censorship office continued to operate; however, it was somewhat more permissive due to the new press laws of 2001.

State-Press Relations

During the military dictatorship, the press was curtailed with Article 6(b). The military government successfully blacklisted foreign journalists from entering Chile and were able to threaten Chilean journalists with expulsion or worse if they failed to follow regulations. Most press activity was under official pressure and expressed pro-regime sympathies. El Mercurio , Chile's right-wing and most influential newspaper, occasionally printed brief human-rights stories, which gave little explicit information. Torture, for example, was described as "illegitimate pressures" from "unidentified captors" (Spooner).

In the 1990s, the press was cautious, given the repression it had experienced under the years of military rule. In 1998, Alejandro Guillier Álvarez, a news anchor on Chile's national television station, TVN, said government statistics showed that 80 percent of the news in Chile, came from official state agencies.

In the past, conservative senators and authorities blamed journalists and media of portraying them badly or of having excessive bias. In most cases, conservative politicians or authorities, dissatisfied with coverage, attempted to discredit the report by claiming the press information was inaccurate or exaggerated. Politicians' accusations could potentially make the general public question the legitimacy of journalists' reports. During the campaigns of Congressional diputados (deputies) in November 2001, for example, the candidate René Manuel García of the right-wing party National Renovation, accused the press of "making a campaign against two areas of his district, Villarrica y Pucón." He discussed the validity of the press opinions on the national TV-news program, Parlamentarias 2001 , and in a daily of northern Chile, Austral . García accused the press of reporting false and exaggerated stories of his district and thereby hurting the tourist market and the region.

In another case, also in 2001, one prominent journalist, Juan Pablo Cárdenas, editor of the on-line daily, Primera Linea , was fired as a result of alleged government pressure. His reports allegedly did not violate any laws, but some officials did not like the coverage.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

During the Allende government (1970-73), thousands of international scholars, writers, intellectuals, and journalists arrived in Chile to study and document the Socialist government. The Allende government welcomed them to observe the South American experiment in Socialist politics.

After the coup in September 1973, Pinochet ordered the capture of thousands of alleged enemies of the state. Among those captured, imprisoned, and tortured or who "disappeared" were foreign investigative journalists, intellectuals, and diplomats. One of the best known of the disappearances was that of the U.S. intellectual Charles Horman, who was investigating and discovered the extent of United States' supposed involvement in the coup. Horman disappeared a few days after the coup and was killed on September 19, 1973 allegedly for knowing "too much" about supposed U.S. involvement in supporting Pinochet's bloody coup. Other foreign nationals from the United States and from Spain, Argentina, and other nations were also arrested or disappeared during the dictatorship.

Pinochet manipulated and used the foreign media to present a softer international image. According to Mary Helen Spooner, Soldiers in a Narrow Land , in the 1970s and 1980s, the military government successfully blacklisted foreign journalists from entering Chile. These blacklisted journalists were considered cumbersome. Investigative journalists who were allowed to stay in Chile were likely to be those considered "compliant." Spooner described one rare press conference on August 16, 1984, that Pinochet gave for foreign journalists at the La Moneda presidential palace. The session was off the record and no tape recorders were allowed in the conference. Foreign journalists filed their stories from handwritten notes and when that afternoon, they picked up the text for the foreign media, she described how, "the document, bearing the seal of the presidential press secretary's office, was markedly different from what Pinochet had actually said. Not only was the text incomplete, but it included questions that had not been asked and remarks that Pinochet had not made" (Spooner 11). For example, "when asked about his plans after leaving the presidency, Pinochet said, according to the official transcript, 'Now, what happens with me, history will tell.' His real response had been more apocalyptic: "Now, when I finish they can kill me as I expect. I'm a soldier and I'm ready"' (Spooner 12).

In the 1990s, Chilean journalists and advocates of free speech welcomed foreign journalists and scholars as instructors to teach their young students of journalism. Doing so was intended to adequately train new journalists in the post-Pinochet era. Most Chilean journalists valued West European and North American standards of journalism and considered these standards as a goal worth reaching. These two regions seemingly highly valued the rights of free speech and they had laws protecting access and freedom of information, had independent press systems, and individuals were free to speak or write frankly on the administration of the State or any other subject.

The Chilean press was severely curtailed during the dictatorship, and later it slowly recovered. The prestigious School of Journalism of the University of Chile developed a Center for the Study of the Press in the late 1980s and created links with the North American association, the Accrediting Council of Education and Mass Communication. Administrators of the school stated that such connection could improve the school's standards and training methods.

Broadcast Media

As of 2002, Chile had many radio and television broadcast stations, as well as an increasing number of Internet users. As of 1998, Chile had 180 AM and 64 FM radio broadcast stations. There were 5.18 million radios. In 1997, there were 63 local and national television broadcast stations. There were also 23 branches of foreign news agencies headquartered in Santiago. There were 3.15 million televisions. Chile had five national broadcast television networks. All of them, including the state-owned but autonomous National Television (TVN), were self-supporting through advertising. Television broadcasting stations in Santiago were Channel 4, La Red; Channel 5, Universidad Católica Valparaíso (UCV); Channel 7, Televisión Nacional (TVN); Channel 9, Megavisión; Channel 11, Chilevisión; Channel 13, Corporación de Televisión de la Universidad Católica; and the UHF television station Gran Santiago Television, Channel 21.

Programming depended heavily on foreign series and movies. Dubbed cinema and TV products from the United States predominated. However, Mexican, Venezuelan, Brazilian, Argentine, and Japanese material could also be seen. Locally produced news, magazine shows, variety shows, and soap operas were of high quality and attracted large prime-time audiences.

Cable television reached an estimated 730,000 households in Chile, 51 percent of them in Santiago. Most homes and apartment complexes, particularly in Santiago, were hooked up to receive cable. For some renters, access to cable was included in the monthly rent payments. Two major cable systems, Metropolis-Intercom and VTR-Cabled, enjoyed near monopoly status in the business as they provided cable services to 95 percent of the country. Both cable companies rebroadcast all local stations, as well as major international channels from the United States, Italy, France, Germany, Argentina, Brazil and Mexico.

U.S. programs offered to Chilean audiences included Cable Network News International (CNN International), Music Television (MTV), Turner Network Television (TNT), Worldnet, the Sports cable network (ESPN), Cartoon Network, Home Box Office-Olé (HBO Olé), and Maximum Service Television (MSTV). MSTV is a forty-five-year old national association of local television stations dedicated to preserving and improving the technical quality of free, universal, community-based television service to the public.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, radio was Chile's most extensive mass medium and reached more people in more remote places than any other medium. Nearly all Chilean stations operated commercially, and six had network affiliates. In 1998, the National Radio Association (ARCHI) reported that there were 179 AM and 614 FM stations in the country, with 24 AM and 32 FM stations in Santiago. An estimated 93 percent of Chile's population listened to radio. The figure for Santiago was 97 percent.

In 2000, radio was a prime source of current news to millions of Chileans, and the national networks devoted large budgets to maintaining professional news staff. The number one national network in the metropolitan area of Santiago was Radio Cooperativa (760 AM and 93.3 FM). Two other news radio stations were Radio Chilena (660 AM and 100.9 FM) and Radio Agricultura (570 AM and 92.1 FM). The major musical and commercial FM radio stations were Rock y Pop, Pudahuel-La Radio de Chile, Corazón, Romántica, and Activa.

Electronic News Media

In 2002, many of Chile's dailies were available online for the general audience. People the world over with access to the Internet could read Chilean newspapers and magazines at any time. Some small-scale and local newspaper publishers had turned to digital newspapers in place of printed ones to reduce the risk of low readership and increased overhead and printing costs. Moreover, digital news permitted publishers to offer their readers the most up-to-the-hour or -minute reporting due to the ease of updating websites and working with computer technology. As of 2000, there were seven Internet service

Some of the on-line newspapers included: Agencia Chile Noticias , Condor (German-language); Crónica , regional paper of Concepción; Diarios regionales , published by the El Mercurio -chain; El Chileno (weekly); El Díario (Firms, Economy, and Finance); El Mercurio (national circulation); El Mercurio de Valparaíso (Regional edition); El Mostrador (Santiago daily); El Siglo Digital (weekly in Santiago); El Sur , regional paper of Concep ción; Estrategía (Business magazine); Infoweek , a weekly on business, Internet, and technology. Many others existed that reflected the diverse reading culture of Chile.

Other online news media included: La Cuarta Cibernética ; La Otra Verdad (The Other Truth), which was written by independent citizens; La Tercera , the Santiago-based paper published by COPESA; Las Últimas Noticias , published by COPESA; La Voz Arauco , a local paper of Canete; Prensa al Día , compilation of news of the day published by Chilean newspapers; Prensa Austral , a local paper of Punta Arenas; Primera Línea , an online only newspaper; and last, the Santiago Times , an online daily in English-language.

Education & TRAINING

Chile has fully accredited journalism and mass media programs. By law, any Chilean in pursuit of a career in journalism must attend an accredited and recognized journalism school to receive the full title of journalist. In 1987, students graduating from all schools of journalism in the country numbered 4,058, of which 2,690 were women.

Two of the larger and more prestigious journalism schools in Chile were the Facultad de Comunicaciones

In 1983, the School of Journalism of the University of Chile expanded its centers and established the Center for the Study of the Press. The Center had affiliations with press firms and published the magazine, Cuadernos de Información . In 1987, the School of Journalism expanded its degree programs to include the credential of Licenciado en Información Social (equivalent to a bachelor's degree in social information) to the professional title of Journalist.

At the start of 1998, the School of Journalism of the University of Chile continued to expand and created the Faculty of Communications, which was a part of the School of Journalism. On May 1, 1998, the school was approved for acceptance in the Accrediting Council of Education and Mass Communication. This latter association unites the best institutions of journalism in North America.

Summary

From 1973 to 1989, the Chilean press was reduced to pro-regime rhetoric under Pinochet's repressive rule. After 1990 the Chilean press gradually regained its confidence and actively promoted freer press laws. In 2001, the "Law on Freedoms of Opinion and Information and the Practice of Journalism" was signed into law. Although it had some features that promoted a less-than-independent press, the law was a huge feat for a country that had been under military rule for nearly two decades. A free, responsible press is a necessity to the operation of a truly democratic society.

Moreover, Chilean journalism was improving in quality and promoted high-quality reports. Journalists were using the Chilean National Ethics Committee (self-regulating organization similar to the former national news council in the United States) to promote high caliber journalism by reporting scrupulous coverage by competing investigating journalists. Moreover, in the late 1990s, there was increased media competition. This was ideal in part because it made news organizations evaluate and criticize competitors. In the past, this competition helped to increase the diversity and quality of news reporting. Fernando Paulsen Silva, editor of La Tercera , noted that increasing media competition in Chile made news organizations watch and compare the quality of programming. On February 27, 2000, his newspaper complained to the Chilean National Ethics Committee. He accused one of his competitors of inventing bylines to give readers the impression that it had sent staff members around the world to cover soccer games, when in fact he said the news was being rewritten from the Internet.

Under Chilean President Lagos, the press was active in reminding the president that they refused to be relegated to an auxiliary position. More important, in Latin America generally, efforts were made by presidents to free archival police files covering up the disappearances of hundreds of victims during covert government operations against alleged dissidents. Overall, the future of the press in the Latin American region, and particularly the Chilean press, was bright and members of the press and others hoped that one day it would promote even freer laws.

Significant Dates

- 1989, 1993, 1997: The democratically elected presidents, Patricio Alywin and Eduardo Frei, sign into law amendments to Pinochet's Constitution of 1980 in order to allow more permissive press dispersal of information.

- Autumn 1998: Pinochet is arrested in London and placed under house arrest for human rights abuses. Pinochet steps down as commander of the armed forces.

- 2001: Chilean president Ricardo Lagos signs the "Law on Freedom of Opinion and Information and the Practice of Journalism."

Bibliography

Association of Independent Journalists (South American Cone). "Chile." Available from www.asociacionperiodistas.org/ultimagresion/chile.htm .

Bethell, Leslie, ed. Chile Since Independence. Cam-bridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). World Factbook 2001 . Directorate of Intelligence, 2002. Available from www.cia.gov/ .

"Chile" World Press Freedom Review, 1997-2001. Available from www.freemedia.at/wpfr/ .

"Chile gauges impact of increased immigrant population." CNN Interactive, World News Storypage, October 14, 1996. Available from www.cnn.com .

"Chilean Media." 2002. Available from www.corporateinformation.com/clsector/Media.html .

"Chilean regime signs electoral pact with Communist Party." 2002. Available from www.wsws.org/ .

Collier, Simon and William F. Sater. A History of Chile, 1808-1994. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

"Pinochet Quits Senate Post." July 2001. Available from news.bbc.co.uk/ .

Spooner, Mary Helen. Soldiers in a Narrow Land: The Pinochet Regime in Chile. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

U.S. Department of State. "Chile—Country Commercial Guide." 2001.

Wilkie, James, Eduardo Alemán, and José Guadalupe Ortega, eds. Statistical Abstract of Latin America, vol. 36. Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center Publications, University of California, 2000.

Yovanna Y. Pineda

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: