China

Basic Data

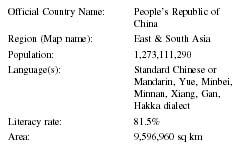

| Official Country Name: | People's Republic of China |

| Region (Map name): | East & South Asia |

| Population: | 1,273,111,290 |

| Language(s): | Standard Chinese or Mandarin, Yue, Minbei, Minnan, Xiang, Gan, Hakka dialect |

| Literacy rate: | 81.5% |

| Area: | 9,596,960 sq km |

| GDP: | 1,079,948 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Daily Newspapers: | 816 |

| Total Circulation: | 50,000,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 54 |

| Number of Nondaily Newspapers: | 1,344 |

| Total Circulation: | 138,000,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 148 |

| Total Newspaper Ad Receipts: | 12,776 (Yuan Renminibi millions) |

| As % of All Ad Expenditures: | 32.50 |

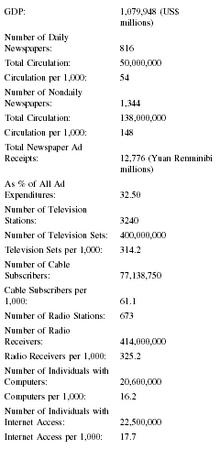

| Number of Television Stations: | 3240 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 400,000,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 314.2 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 77,138,750 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 61.1 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 673 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 414,000,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 325.2 |

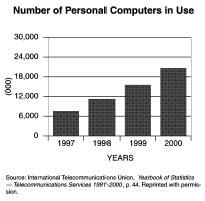

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 20,600,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 16.2 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 22,500,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 17.7 |

Background & General Characteristics

As a monopolistic regime, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is committed to the Marxist-Leninist-Maoist emphasis on the central control of the press as a tool for public education, propaganda, and mass mobilization. The entire operation of China's modern media is based upon the foundation of "mass line" governing theory, developed by China's paramount head of state, Mao Zedong. Such a theory, upon which China's entire political structure hinges, provides for government of the masses by leaders of the Communist Party, who are not elected by the people and therefore are not responsible to the people, but to the Party. When the theory is applied to journalism, the press becomes the means for top-down communication, a tool used by the Party to "educate" the masses and mobilize public will towards socialist progress. Thus the mass media are not allowed to report any aspect of the internal policy-making process, especially debates within the Party. Because they report only the implementation and impact of resulting policies, there is no concept of the people's right to influence policies. In this way, the Chinese press has been described as the "mouth and tongue" of the Party. By the same token, the media also act as the Party's eyes and ears. Externally, where the media fail to adequately provide the public with detailed, useful information, internally, within the Party bureaucracy, the media play a crucial role of intelligence gathering and communicating sensitive information to the central leadership. Therefore, instead of serving as an objective information source, the Chinese press functions as Party-policy announcer, ideological instructor, intelligence collector, and bureaucratic supervisor.

China's modern media, which were entirely transplanted from the West, did not take off until the 1890s. Most of China's first newspapers were run by foreigners, particularly missionaries and businessmen. Progressive young Chinese students who were introduced to Western journalism while studying abroad also imported the principles of objective reporting from the West. Upon returning home, these students introduced the methods of running Western-style newspapers to China. The May Fourth Movement in 1919, the first wave of intellectual liberation, witnessed the publishing of Chinese books on reporting, as well as the emergence of the first financially and politically independent newspapers in China. However, the burgeoning Chinese media were suffocated by Nationalist censorship in the 1930s. Soon after the Kuomintang (KMT) gained control of China in 1927, it promulgated a media policy aimed at enforcing strict censorship and intimidating the press into adhering to KMT doctrine. But despite brutal enforcement measures, the KMT had no organized system to rein in press freedom, and when times were good, it was fairly tolerant toward the media. The KMT gave less weight to ideology than the CCP eventually would and therefore allowed greater journalistic freedom.

Chinese journalism under CCP leadership has gone through four phases of development. The first period started with the founding of New China in 1949 and ended in 1966, when the Cultural Revolution began. During those years, private ownership of newspapers was abolished, and the media was gradually turned into a party organ. Central manipulation of the media intensified during the utopian Great Leap Forward, wherein excessive emphasis on class position and the denunciation of objectivity produced distortions of reality. Millions of Chinese peasants starved to death partly as a result of media exaggeration of crop production.

During the second phase (1966-78), journalism in China suffered even greater damage. In the years of the Cultural Revolution, almost all newspapers ceased publication except 43 party organs. All provincial CCP newspapers attempted to emulate the "correct" page layout of the People's Daily and most copied, on a daily basis, the lead story, second story, number of columns used by each story, total number of articles, and even the size of the typeface. In secret and after the Cultural Revolution, the public characterized the news reporting during the Cultural Revolution as "jia (false), da (exaggerated), and kong (empty)."

The third phase began in December 1978, when the Third Plenary Session of the Eleventh Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party convened. Deng Xiaoping's open-door policy brought about nation-wide reforms that nurtured an unprecedented media boom. The top agenda of media reform included the crusade for freedom of press, the call for representing the people, the construction of journalism laws, and the emergence of independent newspapers. Cuts in state subsidies and the rise of advertising and other forms of financing pointed the way toward greater economic independence, which in turn promoted editorial autonomy.

The Tiananmen uprising in 1989 and its fallout marked the last phase. During the demonstrations, editors and journalists exerted a newly-found independence in reporting on events around them and joined in the public outcry for democracy and against official corruption, carrying banners reading "Don't believe us—we tell lies" while marching in demonstrations. The students' movement was suppressed by army tanks, and the political freedom of journalists also suffered a crippling setback. The central leadership accused the press of engaging in bourgeois activities such as reflecting mass opinion, maintaining surveillance on government, providing information, and covering entertainment. The once-hopeful discourse on journalism legislation and press freedom was immediately abolished. With the closing of the political door on media expansion, the post-Tiananmen era witnessed a dramatic turn towards economic incentives, allowing media commercialization to flourish while simultaneously restricting its freedom in political coverage. These developments produced "the mix of Party logic and market logic that is the defining feature of the Chinese news media system today" (Zhao 2).

The media expanded more rapidly after Mao's death than at any other time in Chinese history. As of October 1997, China had more than 27,000 newspapers and magazines. Chinese newspapers can be divided into several distinct categories. The first is the "jiguan bao" (organ papers). People's Daily and other provincial party newspapers are in this category. The second is the trade/professional newspapers, such as Wenhui Ribao (Wenhui Daily), Renmin Tiedaobao (People's Railroads), and Zhongguo Shangbao (Chinese Business). The third is metropolitan organs (Dushibao), such as Beijing Qingnianbao (Beijing Youth Daily), Huaxi Dushibao (Western China Urban Daily), and other evening newspapers. The fourth is business publications, such as Chengdu Shang bao (Chengdu Business Daily) and Jingji Ribao (Economics Daily). The fifth is service papers; Shopping Guideand Better Commodity Shopping Guide are two examples. The sixth is digest papers, such as Wenzhaibao (News Digest), and finally, army papers: Jiefangjun Ribao (People's Liberation Army Dail) belongs to this category. Besides these types of formal newspapers, there are tabloids and weekend papers. The Chinese "jietou xiaobao" (small papers on the streets) are the equivalent of tabloids, which are synonymous with sensationalism in China. In addition to tabloids, major newspapers seeking a share of the human-interest market also created zhoumo ban (weekend editions). In 1981, Zhongguo Qingnianbao (China Youth News), the official organ of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Youth League, published its first weekend edition in an attempt to increase readership. The paper was an instant success. By the end of 1994, one-fourth of all newspapers had weekend editions. Weekend editions sell well because they are usually more interesting than their daily editions, with more critical and analytical pieces on pressing social issues, as well as various entertainment components.

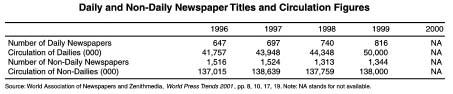

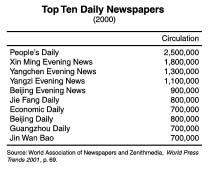

As of March 2000, China had 2,160 newspapers with a total annual circulation of 26 billion (Sun 369). However, these numbers are estimates because newspaper circulation is actually unknown in China. Except for several successful ones, most papers do not give real numbers thus discrepancies exist depending upon the source used. The numbers cited below can only be used as an indication of the general trends. Also, circulation does not necessarily reflect popularity or influence, due to mandatory subscription or larger populations in some areas. The following table lists the 10 largest newspapers with their circulations (Press Release Network, 2001).

- Cankao Xiaoxi (Reference News) 9,000,000

- Sichuan Ribao (Sichuan Dail) 8,000,000

- Gongren Ribao (Workers Daily) 2,500,000

- Renmin Ribao (People's Daily) 2,150,000

- Xinmin Wanbao (Xinmin Evening News) 1,800,000

-

Wenhuibao

(Wenhui Daily) 1,700,000

- Yangcheng Wanbao (Yangcheng Evening News) 1,300,000

- Jingji Ribao (Economic Daily) 1,200,000

- Jiefang Ribao (People's Liberation Army Daily) 1,000,000

- Nanfang Ribao (Nanfang Daily) 1,000,000

- Nongmin Ribao (Farmer's Daily) 1,000,000

- Zhongguo Qingnianbao (China Youth Daily) 1,000,000

The most popular newspaper appears to be Cankao Xiaoxi (Reference News), which is a collection of foreign wire service and newspaper reports in translation with a circulation of approximately 7 to 8 million. It contains international news, including commentary from media sources in Western countries, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. It gives a glimpse into behind-the-scenes domestic policy debates and factional struggles. Initially limited to cadres at or above the jiguan ganbu (agency level), it was as of 2002 available to the Chinese public.

In terms of influence, the next most important newspaper is People's Daily , whose huge circulation is benefited by the mandatory subscription of all Chinese working units. People's Daily runs five subsidiary newspapers, including its overseas edition, which is the official organ for propagating the Party line among the Chinese-reading public overseas. The other four editions include two editions covering economic news, a satire and humor tabloid, and an international news edition. Under Deng Xiaoping's economic reforms, Party and government media organs are no longer simple mouthpieces; they have become business conglomerates.

Beijing Youth News is one of the most influential newspapers among younger Chinese audiences. It began on March 21, 1949, as an official organ of the Beijing Communist Youth League. The paper has been able to make the most of opportunities created by reform and commercialization. Since the early 1980s, it has implemented a series of successful management reforms, refused to accept any "back door" job placements, pioneered the system of recruiting staff through open competition, and eliminated lifetime tenure. From 1994 to 2001, it changed from a daily broadsheet with eight pages to a daily broadsheet with 46 pages, including 14 pages of business information. Its circulation reached 400,000 in 2001, and its advertising income concurrently skyrocketed to 640 million in the same year. In the 1990s, the newspaper grew from a small weekly into a conglomerate that publishes four papers and runs 12 businesses in a wide range of areas.

As of 1997 there were 143 evening newspapers in China. Three of them have circulations of over 1 million. They are the Yangcheng Evening News , Yangzi Evening News, and Xinmin Evening News (China National Evening Newspaper Association). Local evening papers, usually general interest dailies, are among the best sellers. They are under the direct control of the municipal Party propaganda committee and with more soft news content closer to everyday urban life are aimed at urban families.

The huge gap between Chinese urban and rural areas in terms of living standards is reflected in the access to the media and information. Although the majority of the Chinese population are peasants (79%), Chinese media basically serve urban populations since they are more educated and enjoy greater consumption power. Because of high illiteracy rates and the rapid increase of radio and television sets among Chinese peasants, rural residents increasingly use television as their source of information rather than newspapers.

As of 2000, there were 14 English newspapers in China. They are perceived as reporting on China's problems with less propaganda. China Daily , published by the People's Daily , was the first English newspaper to appear in China. It serves as the CCP's official English organ, directed particularly at foreigners in China.

Nationwide, 6 percent of Chinese belong to 56 ethnic minority groups. Just as there are no privately owned newspapers in China, there is no minority-owned newspaper. The overwhelming majority of Chinese newspapers are published in the official Chinese language,

Between 1949 and 1990, almost all Chinese newspapers were distributed through the postal system. However, this changed when Luoyang Daily and Guangzhou Daily started their own distribution company in the late 1980s, followed by a host of other newspapers. As of the beginning of the twenty-first century, 800 newspapers among more than 2,000 distribute through their own networks. Others reach consumers through a variety of channels, such as post offices (both institutional and private subscription), street retail outlets, automatic newspaper dispensers, and occasionally, copies posted on public billboards. While institutional subscriptions provide newspapers to offices, street retail outlets are the major source of newspapers to private homes. In the office, reading free newspapers is considered legitimate political education as part of the job, but newspapers sold on the streets must compete not only among themselves but also with other commodities and for the urbanite's leisure time and cash.

Economic Framework

Because Chinese media have historically been under such strict control of the CCP, unsurprisingly, until the start of economic reform, almost every aspect of media operation was entirely subsidized by the state. Reform and opening gradually promoted financial independence so that at the end of 1992, one-third of the 1,750 registered newspapers were no longer reliant on state support. In 1994, the government began to implement plans to phase out virtually all newspaper subsidies, with the exception of a few central party organs. Several factors have made financial autonomy and commercialization an economic necessity for Chinese media. First, the opening up of China since the 1980s has created a growing demand by foreign and domestic enterprises for effective advertising channels. Second, Chinese governments at all levels have been relatively deprived since economic reform began, due to economic decentralization and the lack of effective tax laws. Finally, public demand for better media service also stimulated investment in new stations, in more newspapers, and in extended broadcasting hours.

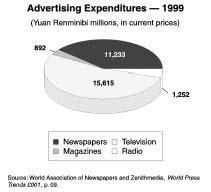

Advertising is the most important form of commercialization in the new Chinese media. In 1992, the four major media—television, newspapers, radio, and magazines—received RMB 4 billion in advertising income, or 64 percent of the total advertising revenue of RMB 6.78 billion. At the beginning of the twenty-first century there were 33 newspapers earning more than RMB 100 million from advertisement.

Commercial sponsorship of specific media content is another form of media commercialization. There are several ways of sponsoring news and information content. In the print media, a sponsor can put its stamp on news, photos, feature articles, and opinion pieces on every page by promoting some sort of competition, usually paying the paper for organizing the contest and providing the cash awards. Sponsors can also support regular newspaper columns or create special columns on chosen subjects under their own names. In the broadcast media, a common form of commercial sponsorship is joint production of feature and information programming. In these programs, government departments or businesses provide money and material while stations produce and broadcast the program.

The new dependence on advertising and sponsorship has had a significant impact on Chinese media. Rather than focusing on political topics, many newly established newspapers and broadcast channels are almost exclusively devoted to business and entertainment. Ratings systems also help advertisers target audiences more effectively. The commercialization of media has also caused the decline of national and provincial organs and the rise of metropolitan organs since the former have more responsibility to cover government policies and political issues while the latter can devote more space to issues of interest to the urban population.

Along with more financial freedom, commercialization has also brought journalistic corruption to China. Journalists, media officials, editorial departments, and the subsidiary businesses of the media often take advantage of their connections with news organizations to pursue their own financial gains. These range from relatively harmless exchanges such as paid travel and accommodations to encourage positive reporting about the news source, to crimes such as "paid journalism," in which journalists receive bribes for publishing promotional material disguised as news or features. Since the late 1980s, systemic journalistic corruption has developed rapidly, expanding from business clients to government clients, from an individual practice to a collective custom, and from small gifts to sizeable cash sums and negotiable securities. Studies comparing Chinese media over the past one hundred years to other Asian and Western media show that the particular connection between news and business in the Chinese media is unique. Chinese journalism corruption is a structural problem, rooted in the contradictions between the Party's ideology and the commercialized environment under which the modern press operates.

Press Laws

Article 35 of the Constitution of the People's Republic of China (adopted on December 4, 1982) stipulates that "citizens of the People's Republic of China enjoy freedom of speech, of the press, of assembly, of association, of procession and of demonstration." Although there has not been any law specifically ascribed as press law, many regulations and administrative orders have been issued to control publications and their distributions since 1949. In late 1994, the Propaganda Department's Six No's were circulated in top journalism and news media research institutions: no private media ownership, no shareholding of media organizations, no joint ventures with foreign companies, no discussion of the commodity nature of news, no discussion of a press law, and no openness for foreign satellite television. This kind of statement, by far the most important media policy statement made by the Party in the 1990s, illustrates the informal and reactive nature of media policy-making by the Chinese Communist Party.

The first step necessary for the Chinese government to control the media was a strict registration and licensing system. As stipulated by the 1990 Provisional Regulations on Newspaper Management, all applications for publishing newspapers must be approved by the State Press and Publications Administration (SPPA), the government's official media monitor. All newspapers must carry an official registration number. Moreover, with the exception of party organs, all must have an area of specialization and must have a "zhuguan bumen" (responsible

Another powerful weapon that the CCP uses to check information flow is to classify an enormous range of information as "state secrets," including harmless information already in the public domain. The Notification on Forbidding Openly Citing Internal Publications of Xinhua News Agency (1998) states that "to maintain the secrecy of the internal publications concerns the Party's and national interests." It made it clear that news media are not allowed to cite any classified documents. This regulation has been conveniently used to imprison citizens who spread critical ideas and information outside of established channels.

Besides maintaining control of the media, the CCP authorities try to tackle the problem of journalistic corruption partly due to public pressure and partly due to concern for the party organ's reputation. A series of codes of ethics have been released since 1991. The first one was the Moral Code for Chinese Journalism Professionals, which emphasizes the principles of news objectivity and fairness. According to the code, journalists "should not publish any forms of 'paid journalism'… should not put news and editorial spaces up for sale, nor accept nor extort money and gifts nor obtain private gain." It also pronounced that "journalism activities and business activities should be strictly separated. Reporters and editors should not engage in advertising and other business activities nor obtain private gain." In January of 2000, the "Chinese Newspaper Self-Discipline Agreement" was released, which stipulates that journalists must strictly follow all regulations and rules passed by the government and assume social responsibilities. Reporters should not "issue false numbers, make untruthful advertisement and groundless accusation, and mix news reporting with advertising activities." The Advertising Law of the People's Republic of China (February 1995) is yet another kind of code of ethics, calling for media institutions and journalists to adhere to the principle of truth, abide by the law and professional ethics, maintain honesty in performing their duties, and defend the reputation and image of the Chinese media. However, these codes of ethics are not binding at all. Enforcement of regulations is weak, often belated, and full of loopholes.

Since the 1980s reformist journalists, educators, and researchers have pushed for a press law that would safeguard journalists' professionalism beyond the vague "freedom of the press" provision in Article 35 of the Chinese Constitution. For different reasons, functionaries concerned with the news media's potential to hamper official business and harm reputations also pushed for such a law, hoping that it might restrain the press from excess zeal. The suppression of the 1989 Student Democracy Movement, however, killed all discussions on a press law. As of 2002, there was no sign that China would pass such a law.

Censorship

Censorship defines the environment in which the Chinese press has operated since the late nineteenth century. The Communist Party, however, exerts the most rigorous and institutionalized forms of censorship in Chinese press history. Vertically, the CCP's Central Propaganda Department commands the propaganda departments of CCP committees at five government levels— central, provincial, municipal, county, and township, as well as individual enterprises and institutions. Horizontally, it controls China's print and broadcast media, journals, books, television, movies, literature, arts, and cultural establishments.

As a matter of control, newspapers have a strict editing system. The Central Committee Secretariat inspects important manuscripts at the People's Daily and the provincial CCP secretary or the secretary in charge of supervising propaganda work inspects provincial newspaper articles. Shendu or shending (media monitoring) is usually performed by special teams of veteran Party ideologues. For editors and journalists, the danger of post-publication retribution is omnipresent. Punishment ranges from being forced to write self-criticism to imprisonment. Although pre-publication censorship is not prevalent, the threat of post-publication sanction results in fairly vigilant self-censorship.

However, China's news apparatus exhibits far more flexibility than a strictly totalitarian model would lead one to expect. In a nation as large and complex as China, authorities cannot hope bring every aspect of the media fully under control. Communication between the Party and the masses is subject to leaks, inference, and distortion. Press censorship cannot always achieve its purpose since the Chinese have learned the art of decoding newspaper messages over the years. For example, if some senior members of the Party are missing from the participants' list on an important CCP gathering, the public learns to interpret this as a sign of a factional struggle within the higher echelons of the CCP, and those missing names indicate a purge.

The fate of the Shijie Jingji Daobao (World Economic Herald) provides a case study of censorship in China. The Shanghai-based World Economic Herald was created in June 1980 as a result of Deng Xiaoping's economic-reform policies which allowed enterprises to start newspapers to promote the exchange of business information and to provide a means of advertising. In order to obtain relative freedom and autonomy in the newspaper's organization and to escape government control, Qin Benli, the founder of the World Economic Herald , established a board composed of prominent scholars and officials to formulate the Herald 's guidelines. He not only appointed some previous "rightists" but also recruited a group of talented young reporters and editors. The Herald had no government funding and started with RMB 20,000 of prepaid advertising money, but sound management led the paper to expand rapidly.

The principle of the paper was to serve as a "mouth-piece for the people" to promote reform and opening. Quickly, the newspaper became a yardstick for measuring the extent of political freedom in the country. In a sense, the paper was the harbinger of the 1989 Student Democracy Movement. Fearing the paper's growing political and financial autonomy, the government wanted to oust Qin Benli and take over the paper. Such efforts were twice defected by reformists at the top of the Party's hierarchy. But on April 24, 1989 the World Economic Herald published an article expressing sympathy for the former General Party Secretary, liberal Hu Yaobang, criticizing those who purged him in 1987. Two days later, Qin Benli was dismissed and the paper was taken over by the Shanghai Municipal Committee. Party officials in Shanghai announced that the World Economic Herald had never been an official newspaper and Qin had never received formal certification regarding his appointment.

State-Press Relations

Theoretically, Chinese citizens have the right to criticize the government. According to the 41st Article of the Constitution,

"Citizens of the People's Republic of China have the right to criticize and make suggestions regarding any state organ or functionary. Citizens have the right to make to relevant state organs complaints or charges against, or exposures of, any state organ or functionary for violation of the law or dereliction of duty, but fabrication or distortion of facts for purposes of libel or false incrimination is prohibited. The state organ concerned must deal with complaints, charges or exposures made by citizens in a responsible manner after ascertaining the facts. No one may suppress such complaints, charges and exposures or retaliate against the citizens making them. Citizens who have suffered losses as a result of infringement of their civic rights by any state organ or functionary have the right to compensation in accordance with the law."

This right is, however, by no means guaranteed. The Fifty-first Article indicates that national, societal, and collective interests cannot be damaged due to individuals' exercise of freedom and their rights. "Citizens of the People's Republic of China, in exercising their freedoms and rights, may not infringe upon the interests of the state, of society or of the collective, or upon the lawful freedoms and rights of other citizens." The CCP General Party Secretary, Jiang Zemin (1997-2002), defines the relationship between the Party's leadership of the press and the people's rights in this way: "The news project of our country is a part of the cause of our Party. So in the press, we must adhere to the principles of keeping the Party's spirits, and maintaining a correct orientation for public opinion. It is not permitted to use so-called 'people's rights' to deny our Party's leadership over the news project." Thus, the Constitution leaves a significant loophole regarding citizens' right to criticize the government. Only the state can determine what national, societal, and collective interests are deemed important enough to override individual rights.

An apparatus for tightening administrative supervision of the press is the State Press and Publications Administration that was set up in January 1987. In addition to offices in charge of policies and regulations, copyrights, foreign affairs, newspaper, periodicals, books, distribution, audio-video, technology development, personnel, and planning and finance, it also governs about 20 publishing houses. It is a ministry-level agency with corresponding agencies at provincial and municipal levels. The Administration serves as the ideological police of every newspaper and magazine in China. It is also in charge of drafting and enforcing press laws, licensing publications, and monitoring texts. However, this agency is under the supervision of the Party's Propaganda Department and thus has no authority over central party newspapers, such as People's Daily and Guangming Daily.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

In both Nationalist and Communist China, foreign correspondents have never been provided information adequately by official sources. Foreign journalists must develop alternative sources, such as embassy personnel, the foreign community in China, and Chinese intellectuals, artists, and dissidents. Sometimes they even make an effort to meet officials under informal, off-the-record circumstances or to befriend the children of high-level officials. Foreign journalists must take extraordinary pains to protect their Chinese sources. In general, foreign correspondents are subjected to surveillance, including the monitoring of telephones and mail. Chinese staff, such as interpreters, drivers, cooks, and maids, are also instructed on their duty to keep an eye on foreign correspondents during their work.

After the Tiananmen student movement in 1989, three sets of regulations were announced for external reporters. The first two sets were for Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macao reporters, issued respectively on September 16, 1989, and October 27, 1989. The third set, "Regulations Governing Foreign Reporters and Permanent Foreign News Apparatus," has been in effect since January 1990, and it delineates the procedure of accreditation and operation of foreign journalists in China. According to the regulations, the Information Department of the Foreign Ministry is in charge of foreign journalists. As for the accreditation process, any news organization must first register with its home government. The Chinese government then has the right to acknowledge or reject its status in China. Finally, foreign journalists must register with the Information Department in order to get "Foreign Correspondent Cards."

In 1991 the Chinese Foreign Ministry directed Chinese embassies abroad to impose stricter standards in screening foreign reporters' visa applications, including extensive background checks, and a review of the political content of each applicant's previous reporting. Chinese missions were held accountable for unfavorable stories by reporters that they cleared. The Chinese government also required special permission to visit areas of minorities.

Even in special economic zones, areas in which foreigners could expect a certain degree of leniency, control over communications has been tightened. In April of 1996, the government issued a 25-article regulation to centralize the distribution of business, economic, and financial news and data. It ordered foreign news providers and their subscribers to register with the state monopoly, Xinhua News Agency. Because business news items have become hot commodities, foreign news services such as Reuters and Dow Jones have developed networks worth tens of millions of dollars by selling up-to-minute stock market quotes and news to more than one thousand private and company clients in China. The regulations not only put strict curbs on foreign news services in reaping profits from this lucrative business but also allowed Xinhua to filter news that is "forbidden" or that "jeopardizes the national interest of China." The real-time information providers as well as news wire and online service providers are required to pay a certain amount of monitoring fees. Xinhua has the authority to decide how and at what price foreign-produced business news can be distributed.

According to Chinese law, no foreign capital can enter Chinese media. The only joint venture that is allowed by the Chinese government is the magazine, Jisuanji Shijie (Computer World), run by a Chinese and an American company. Although a Hong Kong company and a Swiss investor tried to invest in two Chinese newspapers secretly, they were soon discovered and forced to leave. Chinese sources indicated that the situation would remain the same even after China entered the World Trade Organization.

Overall, foreign reporting influence on China has been marginal. Reporters are restricted to urban areas and cannot communicate directly with peasants in the countryside or with industrial workers, partly due to language barriers and partly because of the Chinese government's restrictions. Common problems faced by foreign correspondents include isolation, being treated with distant respect, and being subjected to staged propagandistic events. Although foreign reporters of Chinese descent can be more resourceful and less recognizable in China than their non-Chinese counterparts, there is no evidence that they have been any more influential on China's development. So far, journalists, scholars, and government analysts have not penetrated central politics.

Nonetheless, external challenges to the Chinese media system have never been so strong since China started economic reforms in the 1980s. The news media of Hong Kong and Taiwan are increasingly influential with better economic integration and a common cultural background. Western media influences come in many technological forms, from short wave radio to satellite television to the Internet, and are driven by both political and commercial imperatives. More than 100 international media outlets have set up branch offices in China, including CNN, Reuters, Bloomberg, AP Dow Jones, Newsweek , FortuneNew York Times and many others. Therefore, morning news events in Beijing are likely to be picked up by international wire or TV networks in the afternoon and broadcast worldwide. Generally speaking, the foreign media in China go after political stories and sensitive, provocative issues such as Tibet, human rights and Taiwan's independence movement. And they tend to add a controversial touch or political twist—even in business reports.

Reprinted news dispatches of foreign journalists based in China have been widely perceived in China as more informative about internal developments than Chinese newspapers. Evidence shows that Western reporting on the Democracy Wall movement in 1978-1979 prompted Chinese authorities to halt the movement because the foreign media amplified the effect of the movement. Likewise, Western coverage of the 1983-1984 spiritual pollution campaign helped moderate the intensity of the campaign since the coverage raised foreign investors' concern over the Chinese investment environment.

In addition to international correspondents, foreign short wave radio has also become an important alternative source of news, particularly for intellectuals and university students. A 1990 survey found that 10.6 percent of the Beijing population frequently listened to nearly 20 foreign radio stations. As of 1993, some 27 outside broadcasters (including five in Taiwan) provided Chinese-language broadcasts, comprising a total of 185 channels. Influential foreign short wave stations, like the Voice of America (VOA) and the British Broadcasting Company (BBC), have played a critical role in challenging the CCP's monopoly on information, especially with their reports about events in China during political upheavals such the Tiananmen movement.

Besides journalists and radio stations, direct satellite television broadcasting is also a threat to the CCP's monopolistic control of news and ideology. In addition to CNN and the BBC, more than twenty outside television channels broadcast by satellite to China, including both commercial and government-sponsored stations in such places as Hong Kong, Australia, Japan, France, Germany, and Russia. Although the Chinese government, out of fear of ideological influence from the West, generally forbids the reception of all external television, foreign satellite television has gained considerable inroads in China because the original business in satellite dish sales to business institutions quickly expanded to individual households: by late 1993, more than 11 million Chinese households had satellite dishes. The most wide-reaching outside television threat comes from Hong Kong-based Star TV offering MTV, sports, BBC World Service news (partially translated into Mandarin), family entertainment, and a channel of broadcasts in Mandarin, all on the air 24 hours a day. Star TV was originally controlled by the Hong Kong tycoon Li Jiacheng, who has many business interests in China and close ties with China's top leadership. But in July 1993, Li suddenly sold 64 percent of Star TV to Rupert Murdoch's News Corporation. This change of ownership from a friendly Hong Kong businessman to an international media tycoon further diminished the Chinese government's possibility of cutting off unwanted news. In late 1993, Star TV programs were seen in more than 30 million Chinese households.

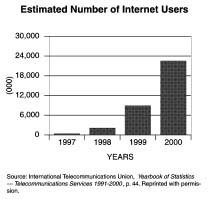

Moreover, access to the Internet is expanding rapidly and the Party's Propaganda Department is again falling behind government departments that have technological and commercial interests in promoting it. China's first electronic mail message was sent through an international connection to a German mail gateway in September, 1987. Among the more than 190 national and regional computer networks registered in China in 1996 are two major academic networks, the China Education and Research Network (CERNET), and the China Academic Science Network (CASNET). These two networks link hundreds of Chinese universities and research institutions to the outside world. In addition, the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications operates Chinanet, which began to provide commercial access to the Internet in May 1995. The Ministry of Electronic Industry is also installing an Internet service. By early 1996 about 100,000 people in China had logged onto the Internet. With the growing popularity of telephones and home computers, many more institutions and urban households will soon access the Internet, and the Propaganda Department will find it hard to restrict computer and telephone use without damaging the economy.

News Agencies

Xinhua News Agency enjoys a monopolistic position as the only CCP-mandated news agency in China. The Chinese Communist Party's news agency, the Red China News Agency, was established on November 7, 1931. Six years later, it was changed to New China (Xinhua) News Agency. The agency not only sent reports to the outside world but also used army radio to collect outside news, mainly dispatches of the Nationalist government's Central News Agency. These were edited and printed in Reference News, which was distributed to Party leaders. Xinhua's tradition of providing intelligence for high-level Party leaders continued as of 2002. By the end of the 1980s, Xinhua had become the largest news organization, with three major departments: domestic with bureaus in all provinces; international with more than 100 foreign bureaus; and the General Office with both domestic and international news editing bureaus, sports news bureau, photo editing bureau, news information center and Internet center. As of 2001, it puts out almost forty dailies, weeklies, and monthlies. Its important subsidiaries include Zhongguo Zhengquan Bao (China Security), a daily that specializes in business news and the stock market, and Xinhua Meiri Dianxun (Xinhua Daily Telegraph), a general interest daily that carries the agency's own news dispatches.

Although Xinhua belongs directly to the highest governmental body, the State Council, its daily operations rely heavily on instructions from various levels of the Party bureaucracy, from the Politburo to the central Propaganda Department. It has the largest and most articulated internal news system of any organization in China, which can be divided into three classes: secrecy, top secrecy, and absolute secrecy. It functions on a need-to-know basis. Those highest in the hierarchy get most fully briefed, while a stream trickles out to the lower level. The system creates a news privilege pyramid. The higher the privilege, the richer the news, the more comprehensive the secrets contained, and the more authoritative the ideas.

Broadcast Media

By the end of the 1980s, Central People's Broadcasting Station (CPBS) and China Central Television (CCTV) had monopolized the broadcast media. They are under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Radio, Film, and Television, which serves as both a news organization and a broadcasting administrative bureaucracy. CPBS's 6:30 to 7:00 morning news and CCTV's 7:00 to 7:30 evening news are transmitted nationwide everyday, making them the most important news programs in the country.

The Central People's Broadcasting Station (CPBS) has established 34 stations nationwide and provides broadcasting and music programs to 34 countries. Popular programs include "Selections from News and Newspapers," "Local People's Broadcasting Stations' Programs," "Small Loudspeaker," "Reading and Appreciation," and "Hygiene and Health." Besides CPBS, every province has at least one radio station under the provincial government, with at least two different channels providing general interest, as well as original programming in specialized areas such as music and business news.

Radio Beijing is the only national station that broadcasts to the world. From 1947 to 1949 all its broadcasts were in English. Then Japanese language programming was added. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, it used 43 languages to broadcast to most countries in the world. After 1984, it opened programs to foreigners in Beijing, and twelve provinces followed suit. It provided programs to more than 20 countries ( Zhongguo xinwen chuban dadian 619).

CCTV, the country's most powerful and influential station, went on the air in 1958. As a state-owned and party-controlled instrument of propaganda, television had limited penetration prior to the 1980s and thus figured insignificantly compared with newspapers and radios before the reform period. However, due partly to a more open political atmosphere and an emerging market economy, and partly to the Chinese Communist Party's intent to use television as an effective means for political and cultural propaganda, television programs became increasingly interesting and more relevant to Chinese daily life. This development resulted in an expansion of television stations, a growth of television-set ownership, and the emergence of an extensive cooperative relationship among stations, commercial financing institutions, and government agencies. CCTV now has 12 channels, including news, social economy and education, entertainment, film, opera, agricultural news, and western China development. CCTV has established relations with more than 120 stations within about 80 countries. As local stations strengthened their capacity for newsgathering and also for producing entertainment fare, they began to be a major program source for CCTV. In 1981, CCTV aired a total of 4,186 news stories; 44 percent of them were furnished by local stations. Of the 118 television dramas that CCTV broadcasted, 81 percent came from local stations.

With the introduction of cable in the mid-1980s, many municipalities and counties, as well as large government units and businesses with their own residential areas for employees, established local cable networks. Because cable stations charge monthly fees, they do not need government investment. As a result, they have developed at an explosive rate and have become highly decentralized. As of the first half of 1993, there were more than 2 thousand cable networks in the country reaching into 20 million households. Approximately 800 were full-scale cable stations, broadcasting videos or self-produced programming. Two hundred of these were run by large-scale state-owned business enterprises. At the end of 1995, the number of full-scale cable stations had reached 1,200, with an estimated audience of 200 million.

CCTV commenced international newscasts on April 1, 1980. The reception from foreign television news services, such as Visnews (Britain) and UPI Television News Service (The United States), broadened CCTV's world news coverage. China also joined Asiavision, a television consortium among Asian countries, and exchanged news with the African Broadcasting Union and World Television Network.

Electronic News Media

The Internet age undoubtedly poses major challenges to the Chinese propaganda authorities. With the

By 2000, China had 10 million Internet users. About 18 percent of households in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhou enjoy net access. Twenty-seven percent of China's Internet users chatted on AOL's messaging service. China now has 3,000-odd enterprises engaged in Internet-related and other value-added endeavors. As of June 2001 almost 1,000 Chinese newspapers—nearly half—were on online. Some well-known Internet press sites included People's Web, established by People's Daily in 1997 and one of the biggest Chinese news web. By providing easy access to a wide range of business information, photos and syndicated cartoons, chinadaily.com.cn has grown into an influential provider of information for people in and outside China. It was the only English-language newspaper Web site that made it into the country's top 10 news portal list. It was recommended by America Online as one of the global leading news websites. Another influential press site is the Qian Long Xin Wen Wang (Thousand Dragon Newsnet), which was formed by nine press institutions in Beijing on March 17, 2000. Its aim is to become the biggest newsnet for Chinese worldwide. A third popular newsnet is Saidi Wang (Saidi Net). It was started by eight information technology institutions in March of 2000. In the south, almost at the same time, Shanghai Liberation Daily, Wenhui-Xinmin Joint Newspaper Group, Dong Fang Radio Station and Dong Fang TV Station started to discuss the formation of Shanghai Dong Fang Net. Both Thousand Dragon Newsnet and Shanghai Dong Fang Net are based on joint efforts between the printed media and the broadcast media.

The Chinese government has issued a number of rules and regulations to control the content of the Internet. Regulations issued in January 2000, for example, stated that media must obtain a qualification certificate to disseminate information online. It also ruled that Internet users charged with violating China's strict security laws could face sentences of up to life in prison. In November 2000, Beijing issued "Temporary Regulations on Internet News Business Management," which stipulated that electronic news media have the right to report news while Internet business sites can only repeat news items that are reported by the news media.

At least seven people have been arrested for Internet-related journalism in China, and more arrests are likely. Lin Hai, the first person in China sentenced in connection with the Internet, was arrested due to his supply of 30,000 e-mail addresses to an overseas electronic newsletter. Huang Qi's website " " grew out of an electronic billboard for missing persons and developed into a discussion forum where people reported human rights abuses that were neglected by the official Chinese press. He was detained by the public security department in Chengdu, Sichuan in June 2000.

About twenty provinces were creating Internet "police" forces, according to Xinhua, with the task of "maintaining order" on the Internet. Meanwhile, criminal statutes were revised to allow for the prosecution of online subversion, limiting direct foreign investment in Internet companies and requiring companies to register with the information that might harm unification of the country, endanger national security, or subvert the government. Promoting "evil cults" (an obvious reference to Beijing's campaign against Falun Gong) was similarly banned, along with anything that "disturbs social order." The regulations also covered chat rooms, a popular feature of many Chinese sites, where the anonymity of cyberspace fosters discussion of democracy and the shortcomings of the ruling elite. Under the new rules, all service providers had to monitor content in the rooms and restrict controversial topics.

The explosion of electronic news media also creates copyright issues in China. In China's first Internet copyright lawsuit, a Beijing court ordered an Internet company to compensate six prominent writers for publishing their work without consent. The court ruled Century Internet Communications Technology Co. had violated copyright laws by putting the works on Beijing Online's

Education & TRAINING

Journalism is becoming an increasingly popular subject among Chinese youth. As of April of 2002, journalism studies were offered in 232 colleges and universities in China. The most popular subjects are TV-broadcast editing and news anchoring. The journalism departments at Beijing University, Wuhan University, and People's University are the most prominent in the country. Beijing University, which opened the first journalism course in China over 80 years ago, re-opened its School of Journalism and Communication in 2001. The new school consists of three departments and one institute. They are the Journalism Department, the Communication Department, the New-Media and Internet-Communication Department, and the Institute of Information and Communication Research. The curriculum and research fields cover journalism, communication, international communication, advertising, editing and publishing, Internet communication, and inter-cultural communication.

The Journalism Department of Wuhan University was founded in 1983. It became the College of Journalism and Communication in 1995. The college has six departments: Journalism, Broadcast Television, Advertisement, Print Communication, Packaging Design, and Internet and Communication. It also offers graduate journalism degrees.

The Journalism Department in People's University was established in 1955, and it became the School of Journalism in 1988. It is one of the two programs that offer Ph.D. degrees nationwide, and the only key subject under the State Education Commission. The department also publishes two magazines, Journalism Studies and International News Media .

In 1980 many young journalists started to take English-language journalism courses from foreigners who began teaching Western journalistic norms in several schools in Beijing and Shanghai. Chinese-language journalism departments, such as those at People's University and Sichuan University in Chengdu, also began expanding their curriculum and embracing the ideal of objectivity, using the American media as an example to be emulated.

However, compared to other subjects of study, journalism is still one of the most guarded. All journalism students are required to take political indoctrination courses on works by Marx, Lenin, and Mao on journalism, and Deng's ideas about the socialist market economy. Reporters and editors nationwide are being forced to attend refresher courses on the role of the media in China's Communist society. Also, anyone who wants to work for a government agency such as Xinhua must become a member of the Communist Party first.

There are four major journalistic organizations in China, and they are all government organizations. The All-China Journalists Association is the first professional organization for Chinese reporters. The organization has a domestic department and foreign affairs department. The former is responsible for training reporters, organizing newsgathering, and sponsoring discussions. The latter is in charge of exchanging programs with foreign journalists and holding press conferences.

China Radio and Television Society was founded in 1986. There are 36 subdivisions, seven offices and seven research committees nationwide. Its objectives are organizing members' research activities to improve the quality of broadcasting and TV programs, giving policy advice, organizing conferences, publishing society's reports, documents, and research results. China Newspaper Publishers' Association (CNPA), founded in 1988, is under the Press and Publication Administration, and affiliated with the People's Daily . It publishes a monthly magazine, Newspaper Management. Membership has reached more than 1,000.

Chinese Publishers Association was created in December, 1979. Besides ordinary functions assumed by other professional organizations, such as assisting government propaganda nationwide and promoting cultural exchanges with foreign counterparts, organizing academic activities is one of its major functions. It issues Taofen Prize, named after a famous Chinese journalist and writer, every two years. It also publishes China Publication Yearbook.

Summary

China's entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 undoubtedly brought changes to Chinese media and publication businesses. According to the State Press and Publication Administration, within one year after joining WTO, China would probably allow foreign media to set up joint book and newspaper retail stores in five special economic zones and eight cities. Mergers would also become increasingly prevalent in China's WTO era. Media conglomerates emerged in the mid-1990s at provincial level and in major cities. These newspaper giants published books, magazines, audio-video materials and newspapers, and they run radio, TV stations, and Internet sites. As of the beginning of 2000, there were 15 media giants in China. The two reasons for the merger fever are media heads' frequent visits to their counterparts in Western countries and the desire to combat increasingly intense competition on China's media market. In January, 1996, the Press and Publication Administration approved the creation of China's first newspaper group, Guangzhou Daily Newspaper Group, the richest Chinese newspaper at the time. By 1998, it had increased to ten newspapers and one magazine with a circulation of 920,000. The advertising income reached 1.5 billion. Based on the successful operations of Guangzhou Daily Newspaper Group, Beijing approved two other newspaper conglomerates in Guangzhou in May of 1998: Nanfang Daily Newspaper Group and Yangcheng Evening Newspaper Group. Guangming Daily and Economic Daily are the first two newspapers in Beijing that formed newspaper conglomerates. Some of the newspaper groups are now trying to enter the stock market overseas to obtain more funds for expansion. It is predicted that by 2010 China will develop 20-30 more newspaper conglomerates (Sun 327).

The goals that the Press and Publication Administration set for Chinese press to achieve in the first decade of the twenty-first century are:

- double the publication volume of both newspaper and audio-video material

- build 5-10 publishing groups with an income between RMB 1 billion and 10 billion and 20-30 of about RMB 1 billion

- advertising income will make up 80% of total income of newspaper companies

- promote newspaper retail by developing newspaper dispensers

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, in order to win press reform, undertake investigative journalism, and truly function as their society's watchdogs, Chinese media still have a long way to go. Since the start of reforms, the Chinese news media have been in the paradoxical situation of at once being changed and remaining the same. Economic reforms and an open-door policy introduced market logic into the party-controlled news media system. But the discourse on media democratization that emerged was suppressed in the crackdown on the democracy movement in 1989. Ironically, this promoted media liberalization by forcing the Chinese press to turn to market forces in a vacuum of political freedom. These developments produced the mix of party logic and market logic, forging the tension, contradiction, and uncertainty that is the unique hallmark of the Chinese media system.

Significant Dates

- October 1997: The first English Edition Chinese newspaper, China Daily, Hong Kong Edition, is issued (Zhongguo Chuban Nianqian (China Publication Yearbook), 1999. Chinese Publication Yearbook (ed.), 1999: 41).

- June 1998: The "three fixes" are implemented to streamline the administrative structure of the press. The three fixes mandate: "fix the number of employees, fix the workload and fix the post."

- August 2000: China's first TV station, Sun TV, starts its program in Hong Kong.

- January 2001: Shanghai begins China's first digital TV program. Other cities, such as Shenzhen, Qingdao, and Hangzhou, follow suit quickly.

- December 2001: The largest Chinese media, China Broadcasting and Television Group, is created in Beijing.

- December 2001: China Human Rights Web site ( http://www.humanrights-china.org/ ) goes online. A project of the China Society for Human Rights Studies (CSHRS), it is the official Chinese human rights Web site, with reports of current human rights conditions, government documents and White Papers, relevant laws and regulations, and links to various state organizations, NGOs, and academic institutions.

- January 2002: China's Ministry of Radio, Film and Television and American Time and Warner start broadcasting 24 hours daily CCTV English news (CCTV, Channel 9) in New York, Houston, and San Francisco. In return, China allows Time Warner's Mandarin programs (ETV) to broadcast in southeast China. This is the first foreign TV program to be shown in China.

Bibliography

Berlin, Michael J. "The Performance of the Chinese Media during the Beijing Spring." In Chinese Democracy and the Crisis of 1989: Chinese and American Reflections . Eds. Roger V. Des Forges, Luo Ning, Wu Yen-bo, 263-273. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press, 1993.

Britton, Roswell S. The Chinese Periodical Press, 1800-1912 . New York: Paragon, 1966.

"China Release New Rules for Foreign News Agencies." Wall Street Journal , 17 April 1996, PB7(W), PB9(E), col. 1.

China Publication Yearbook . Beijing: China Publishers Association, 1999.

Des Forges, Roger V., et. al. Chinese Democracy and the Crisis of 1989: Chinese and American Reflections . Albany, New York: State University of New York Press, 1993.

Dobbs, Michael. "Journalists Link Press Freedom with Aims of Student Protesters." Washington Post , 23 May 1989, p. A18, 28.

Faison, Seth. "The Changing Role of the Chinese Media." In Perspectives on the Chinese People's Movement: Spring 1989 . Ed. Tony Saich, 144-162. Armond, New York: M. E. Sharpe, 1990.

Holman, Richard L. "Press Freedom in Hong Kong." Wall Street Journal , 6 Oct. 1993, p. A14(W), p. A12(E), col. 2.

——. "Chinese Journalists Warned." Wall Street Journal , 5 August 1993, p. A9(W), p. A4(E), col. 4.

——. "China Reduces Media Access." Wall Street Journal , 22 Oct. 1991, p. A16(W), p. A17(E), col. 3.

Kristof, Nicholas. "Beijing Delays Law on Free Press." New York Times , 27 June 1989, p. A4(N), col. 1.

Lee, Chin-Chuan. China's Media, Media's China . Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1994.

——. Voices of China: The Interplay of Politics and Journalism . New York: The Guilford Press, 1990.

Lin, Yutang. A History of the Press and Public Opinion in China . New York: Greenwood Press, 1968.

Liu, Liqun. "The Image of the United States in Present-Day China." In Beyond the Cold War: Soviet and American Media Images . Eds. Everette E. Dennis, George Gerbner, and Yassen N. Zassoursky, 116-125. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc., 1991.

Lynch, Daniel C. After the Propaganda State: Media, Politics, and "Thought Work." In Reformed China . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1999.

MacKinnon, Stephen R. "Press Freedom and the Chinese Revolution." In Media and Revolution . Ed. Jeremy D. Popkin, 174-188. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 1995.

——. "The Role of the Chinese and U.S. Media." In Popular Protest and Political Culture in Modern China: Learning from 1989 . Eds. Jeffrey N. Wasserstrom and Elizabeth J. Perry, 206-214. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1992.

MacKinnon, Stephen R., and Oris Friesen. China Reporting: An Oral history of American Journalism in the 1930s and 1940s . Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1987.

Nathan, Andrew. Chinese Democracy . Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1985.

"New Law for Journalists Proposed," New York Times , 9 Sept. 1980, p. 3(N), p. A6 (LC), col. 3.

Southerland, Daniel. "China Issues Code for Foreign Journalists; New Regulations Seem Designed to Tighten Government Control." Washington Post , 21 Jan. 1990, p. A359.

Sun, Yanjun. Baoye Zhongguo (Newspaper in China). Beijing: China Three Gorge Publishing House, 2002.

Ting, Lee-hsia Hsu. Government Control of the Press in Modern China, 1900-1949: A Study of Its Theories, Operations, and Effects . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1974.

Tyson, Ann Scott. "China Steps Up Harassment of Correspondents," Christian Science Monitor 1 March 1990, 82, no. 65, p. 59.

Widor, Claude. The Samizdat Press in China's Provinces, 1979-1981: An Annotated Guide . Stanford, CA: Hoover Institute, Stanford University, 1987.

Wu Guoguang. "Developemnt of Chinese Mass Media and the Progress of Democratization of Chinese Society." In Essay Collection of Symposium on Election System and Democratic Development in China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong . Ed. Hu Chunhui, 453-491. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University, 1999.

Yang, Meirong. "A Long Way toward a Free Press: The Case of the World Economic Herald." In Decision-Making in Deng's China: Perspectives from Insiders .

Eds. Carol Lee Hamrin and Suisheng Zhao Armond, 183-188. New York: M. E. Sharpe, 1995.

Zhao, Yuezhi. Media, Market, and Democracy in China: Between the Party Line and the Bottom Line . Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1998.

"Zhongguo Xinwen Chuban Dadian." In Encyclopedia of World Media . Beijing: China Archive Publishing Company, 1994.

Ting Ni

thanks a lot .