Colombia

Basic Data

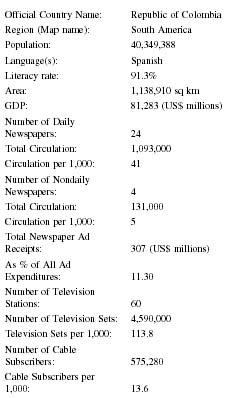

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Colombia |

| Region (Map name): | South America |

| Population: | 40,349,388 |

| Language(s): | Spanish |

| Literacy rate: | 91.3% |

| Area: | 1,138,910 sq km |

| GDP: | 81,283 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Daily Newspapers: | 24 |

| Total Circulation: | 1,093,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 41 |

| Number of Nondaily Newspapers: | 4 |

| Total Circulation: | 131,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 5 |

| Total Newspaper Ad Receipts: | 307 (US$ millions) |

| As % of All Ad Expenditures: | 11.30 |

| Number of Television Stations: | 60 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 4,590,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 113.8 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 575,280 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 13.6 |

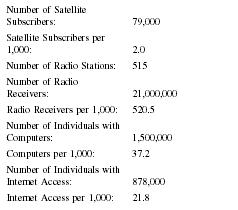

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 79,000 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 2.0 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 515 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 21,000,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 520.5 |

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 1,500,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 37.2 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 878,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 21.8 |

Background & General Characteristics

Colombia is one of the more complicated and interesting of the world's nations. Its history has a significant connection to its media and its press traditions. From its founding as a nation into the twenty-first century, it maintained a tradition of freedom of the press, and it attained an extensive and high quality press. However, violence threatens the country as a democratic entity as well as the health of its media.

Colombian History

The territory that came to be called Colombia was originally populated by Chibcha Indians, who were conquered by Spanish conquistadors (colonialists). The Spanish used the term, Indian, which derived from indigena (indigenous). Although the nation was named for Columbus, the explorer never actually set foot on the land. Spain colonized the territory in the 1600s after conquering the Chibchas.

Originally part of Gran Colombia, which included what are now Panama and Venezuela, Colombia developed a constitution and government in 1811. It began its efforts towards independence from Spain in 1812. When Gran Colombia was liberated at Boyoca in 1819, under the leadership of Bolivar, it became an independent nation. Ecuador joined Gran Colombia in 1822. Panama became part of Colombia in 1821, after gaining its independence from Spain.

The Gran Colombia constitution was a model of popular democratic government. It established a two house or bicameral Congress, guaranteed the inviolability of persons, homes, and correspondence, and also guaranteed freedom of the press. By 1828, however, Bolivar, had returned from liberating other South American nations and had become a dictator and a self-proclaimed president for life. The people of Gran Colombia organized a constitutional convention in 1830, at which time Bolivar resigned. In the process, Ecuador and Venezuela seceded from Gran Colombia, and Gran Colombia collapsed. That left Colombia and Panama as the remaining entities and they essentially became Colombia.

Ethnic Groups

As of 2002, about 58 percent of the people are mestizo (mixed Spanish and Chibcha Indian), and whites are 20 percent. The Spanish brought African slaves who were from the areas now called Angola, Nigeria, and Zaire. Mulattos (mixed black and white) are 14 percent; blacks, 4 percent; and mixed black-Amerindian 3 percent. In addition, Amerindian represent 1 percent of the population.

Population Density

The 2001 estimate of the Colombian population, 40,349,388, suggested a population density of 92 persons per square mile. About three-fourths of the population was classified as urban. One-third of the Colombia people are young. The age distribution was given as follows: younger than 14 represented 31.88 percent; between 15 and 64 represented 63.37 percent; those 65 years and older constituted 4.75 percent. The overall population growth rate was 1.64 percent. The birth rate was 22.41 births per 1,000 population and the death rate was 5.69 deaths per 1,000 people. The population was decreased slightly by a few more people leaving the country than moving to it.

Literacy and Education

The Encarta Encyclopedia estimated that 97 percent of all Colombians could read and write by 2001. In 1996 some 4.9 million pupils attended primary schools and 3.3 million secondary schools. Elementary education was free and compulsory for five years. Most schools were controlled by the Roman Catholic Church, but even governmentally-funded schools required Catholic religion educational content, an arrangement which reflects the close ties between the nation and the Church. There were some Protestant schools, primarily in Bogotá. The government paid for elementary education in communities that could not afford to do so; it also financed secondary and university-level schooling. Late 1990s data showed that 4.9 million pupils annually attended primary schools. Another 3.3 million attended secondary schools including vocational training and teacher training institutions. Of the 235 institutions of higher education some were public and others were affiliated with the Roman Catholic Church.

Religion & Language

In the early 2000s some 95 percent of the people were Roman Catholics. The Concordat between Colombia and the Roman Catholic Church gave that religion a special status in the nation. The rest of the population included some Protestant groups as well as a small Jewish population, many of whom were descendents of individuals who fled Nazi Germany.

Spanish is the dominant language in Colombia. But the 1991 Constitution recognized diverse ethnic groups and made some provision for bilingual education. Dialects characterize different regions of Colombia, and Colombians take special pride in their language and some believe Colombian Spanish to be most closely related to the mother tongue Spaniards brought to Latin America.

Colombian Newspapers

There are 37 Spanish language daily newspapers in Colombia, in addition to two English language dailies, The Colombia Times and The Bogotá Daily. According to 2001 International Year Book: The Encyclopedia of the Newspaper Industry four of the Spanish language papers had circulations of fewer than 10,000; eight had circulations between 10,000 and 25,000; eight others had circulations from 25,000 to 50,000; five had circulations from 50,000 to 100,000; and three had circulations from 100,000 to 500,000.

In Colombia, there were two daily (except for Sunday) newspapers, La Cronica and Diario del Quindio The capital city of Bogotá had several newspapers: Diario , El Espacio (The Space), and El Espectador (The Spectator), considered one of the most influential newspapers in Colombia and Latin America. In Barranquilla, an important port city, there were two newspapers (daily except for Sunday), El Heraldo (The Herald) and La Libertad (The Liberty).

Established in 1925, El Nuevo Siglo was a morning Bogotá paper which also has a Sunday edition and a circulation of 68,000. Begun 1988, La Prensa (The Press), a morning paper without a Sunday edition, had a circulation of 38,000. Started in 1953, La Republica (The Republic), a morning daily newspaper without a Sunday edition, had a circulation of 55,000. Operating since 1911, El Tiempo (The Time), the largest in Bogotá and the nation, had a daily circulation of 265,118 and its Sunday edition, which included supplements, had a circulation of 536,377. El Vespertino (The Evening) was also available afternoons in Bogotá.

In Bucaramanga, El Deber (The Duty) is a morning daily which does not publish on Sundays. El Frente (For-ward) is a morning daily without a Sunday edition, with a circulation of 10,000. Finally, Vanguardia Liberal (Liberal Vanguard) is a daily with a Sunday edition and a circulation of 48,000.

In the city of Cali, El Caleño is a tabloid paper in operation since 1977. Cali also had El Crisol , a morning daily without a Sunday edition, and Occidente , a morning

The resort city of Cartagena had El Periodico de Cartagena (The Newspaper of Cartagena) and El Universal (The Universal) which published both daily and Sunday editions with supplements. In Cucuta, the newspapers included Diario la Frontera (Frontier Daily) and La Opinion (The Opinion). In Girardot, the newspaper was El Diario (The Daily). In Ibague there were two papers, El Cronista and El Nuevo Dia. The town of Manizales had La Patria (Homeland), a morning paper established in 1921.

The major city of Medellin, in Antioquia, had El Colombiano (The Colombian) which was established in 1912. This newspaper published morning and Sunday editions and had an extensive circulation of about 90,000. It was one of the three most influential in the nation, along with El Tiempo and El Espectador of Bogotá.

Many smaller towns had one or more papers. In Neiva there are two newspapers, Diario de Huila (Huila Daily) and La Nacion (The Nation). In Pasto, the two papers were El Derecho (The Right) a morning publication established in 1928, and El Radio (The Radio). In Pereira, El Diario (The Daily) provided a daily but no Sunday edition, and Diario del Otun (Otun Daily) put out an evening newspaper. La Tarde (The Afternoon) was an evening newspaper in Pereira. The morning paper without a Sunday edition, El Liberal (The Liberal), was established in 1938 in Popayan and had circulation of 6,500. The newspaper in Santa Marta was El Informador (The Informer). In Tunja, there were two newspapers, Diario de Boyaca (Boyaca Daily) and El Oriente , a daily. In addition to these general interest daily newspapers, there were many specialized newspapers in Colombia, some dealing with the economy and some with sports. There were also a large number of general interest and special interest magazines published in the country.

Colombian Newspapers: Characteristics and Orientations

Newspapers are an important part of Colombian life. According to the World Almanac and Book of Facts in the early 2000s there were 55 newspapers daily per thousand persons. However, historically there was little communication among the various distinct regions of Colombia. For example, the Department of Antioquia, with its capital of Medellin, was quite distinct geographically and culturally from the capital city of Bogotá and other major cities such as Cali. News and information tended to be local. Moreover, Colombian industry was divided by region. In some sense, each major part of the nation could be seen as a separate nation. These divisions were partly caused by geography. As of 2002, roads were difficult to travel, especially through the high Andean mountains. Air travel, though widely available, was expensive. Therefore, interaction among the regions was not common, and pervasive violence, kidnappings, and robberies discouraged people from going too far from their homes.

Generally, newspapers were of high quality—well-written, well-edited, and generally independent. Colombians depended upon and tended to trust their newspapers, which were widely available and read even across regions. Many of the larger newspapers were readily available through the Internet.

It is possible to infer, from their names alone, the political persuasions of many dailies. Some had "liberal" in their titles, for example. Then, too, the government was an important factor in newspaper business because of its extensive advertising. However, Human Rights Watch and other sources reported that despite the intimidating violence and disorder in the nation, news media independence persisted and papers presented a wide range of political views.

In the early 2000s, Colombian newspapers were mostly owned by wealthy individuals. Human Rights Watch indicated that there was a high concentration of media ownership and, at the same time, fewer advertisers than there had been in the past. Since advertising funds are valued and government is one of the major advertisers,

Colombia's leading television networks and newspapers are run by members of long-standing political and economic elites. The Santo Domingo group, Colombia's largest industrial conglomerate, owns the Caracol TV and radio networks as well as the El Espectador newspaper. The rival RCN TV and radio network is controlled by the Ardila Lulle beer empire. Other prime-time TV news shows and the weekly political magazine Semana are owned by family members of former presidents of the two traditional Conservative and Liberal parties that have held power for the last 150 years.

She also noted that the president elected in 1998, Andres Pastrana, was a former journalist from the Conservative Party.

Robert N. Pierce noted that there was a longstanding Colombian tradition of national leaders who mixed politics and the direction of newspapers. Two other presidents who were newspaper directors preceded Pastrana, Laureano Gómez of the no longer existing El Siglo and Eduardo Santos of El Tiempo . Clearly, newspapers though free are closely tied to the political system.

Economic Framework

Colombia's wealth comes from a number of sources. It has natural resources in petroleum, natural gas, coal, iron ore, nickel, gold, copper, emeralds, and hydropower. Agriculture is a major industry and the following statistics on its land and land use are significant in understanding its magnitude: arable land, 4 percent; permanent crops, 1 percent; permanent pastures, 39 percent; forests and woodland, 48 percent; and other, 8 percent. The nation's agricultural products include coffee, cut flowers, bananas, rice, tobacco, corn, sugarcane, cocoa beans, oil-seed, vegetables, and forest products. It exports petroleum, coffee, coal, clothing, bananas, and cut flowers. In all, it exports US$14.5 billion, half of which goes to the United States, 16 percent to the other Andean nations, 14 percent to Europe, and two percent to Japan. In addition, the country imports industrial equipment, equipment for transportation, chemicals, consumer goods, paper products, and electricity. Although it imports electricity, Colombia produced as of 2002 more than 75 percent of its electricity by hydropower, a renewable and relatively inexpensive source of energy.

The economy of the country has been shrinking. In 1998, Colombia had a gross domestic product of US$102.9 billion, but in 1999 a gross domestic product of only US$88.6 billion. Of course, this gross domestic product figure does not account for sales of illegal drugs, such as cocaine, which constitute a major agricultural crop and industry in the country. According to the Central Intelligence Agency, the cultivation and manufacture of coca, opium, cocaine, and heroin are growing industries in Colombia. The potential production of heroin in 1999 was eight metric tons. As of the early 2000s Colombia supplied 90 percent of the cocaine used in the United States and was a major supplier of the substance to other nations. It supplied large quantities of the heroin brought to the United States. Clearly, the illegal narcotics business contributed to the economy in ways that were contrary to the notions of healthy growth for the nation. These illegal activities were not taxed, a minor issue compared to the fact that much of the earnings from narcotics went into building the narcotics business and into supporting the anti-government forces who threaten to destabilize the nation. These anti-government forces were also responsible for kidnapping and murdering many journalists. So the narcotics trade, in several ways, countered the economic and social growth of Colombia as a nation.

Of course, the narcotics business contributed to the Colombian official economy. For example, individuals operating narcotics productions pay farmers for the produce. They pay employees who process coca and opium into cocaine and heroin and those who traffic in the substances. Those who are paid in turn put their money into the economy by paying for their food, transportation, and shelter. In these and other ways, illegal transactions affect the legal economy. One might also argue that the drug industry also brings U.S. funds into the country: it induces U.S. concern and encourages the United States to send Colombia large sums to use in counteracting the production and distribution of drugs.

In the early 2000s, of the total legal Colombian legal economy, US$61.5 billion of the gross domestic product was composed of services and US$24.4 billion was industry. The remaining US$14.1 billion came from rich Colombian agriculture. On the Caribbean coast, there are mangroves and coconut palms. The forest areas have a variety of trees, including mahogany, cedar, pine, and balsam. Other plants yield rubber, chicle, ginger, vanilla, and many other products. Of course, Colombia is known worldwide for its coffee. The country also produces textiles.

Socioeconomic Structure

In the early 2000s, the Central Intelligence Agency estimated that the lowest 10 percent of the Colombian population, by income, had about one percent of the household income and the top ten percent had about 44 percent of the income. The per capita annual income was about US$6,200 and the inflation rate was nine percent. According to the Encarta Encyclopedia, the upper socioeconomic class in Colombia was largely composed of white people who might trace their family histories to the Spanish colonial period. Their wealth largely came from owning land and other forms of property. Some of these individuals earned their wealth through commercial activities.

The nation had a growing middle class composed of educated, professional people who were successful in business and industry. Some middle class members were teachers, government employees, and professionals in law and medicine, for example.

The lower class lacks adequate housing, health care, and education. In the early 2000s, the Central Intelligence Agency estimated that 55 percent of the Colombian population was below the poverty level. Many lived in rural areas and were employed by wealthy landowners. Labor unions helped to improve the situation of some working poor. Some human services programs were incorporated into the structure of many businesses and industries. In some businesses, the social services programs equaled in value the workers' pay. These social services provided basic education, some counseling, and vacation resorts for workers and their families. Nonetheless, the predominance of low wage employment remained a factor in the growth of the illicit drug industry, which was itself the most important economic and social development in recent Colombian history. In the early 2000s, the total labor force, at all levels, was estimated to be about 18.3 millione. Forty-six percent of those were in service work, 30 percent in agriculture, and 24 percent in industry.

Government

As of 2002, Colombia was divided into 32 departments and the one capital district, which was officially called Distrito Capital de Santa Fe de Bogotá. The nation operated under the 1991 constitution which defined three democratic governmental branches. Men and women age 18 or older were eligible to vote.

As of the early 2000s, Colombia was a republic dominated by an executive branch. The executive branch was headed by a president who was elected for a four-year term. The president governed with a cabinet, which was a coalition of representatives from the two major political parties. There was also a vice-president elected by popular vote. In the 1998 elections, runoffs were needed when no candidate initially received more than 50 percent of the vote. The president and vice-president who were elected in 1998 received just slightly more than 50 percent of the vote each in the runoff.

The Congreso , Colombia's bicameral legislature, consisted of the Senado (Senate) with 102 members elected for four year terms and the Camara de Representantes (House of Representatives) with 163 members also elected for four year terms. Of the two main political parties, the Liberal Party and the Conservative Party, the Liberal Party had a much larger proportion of the Congreso membership (about half) than the Conservative Party. Smaller parties were also usually represented. In 2002, the president was an independent.

Although the Colombian law is based on Spain's, the judiciary was organized similarly to the system maintained in the United States. The judicial system could, for example, exercise judicial review, not a common function of courts in the Spanish tradition.

In addition to the two traditional parties, there were the Patriotic Union (UP), a legal party formed by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the Colombian Communist Party (PCC), and the 19 of April Movement Party (M-19).

Besides political parties, the country contended with powerful insurgent groups that caused great difficulty for the government. The two largest were the National Liberation Army (ELN) and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). The largest paramilitary group is United Self-Defense Groups of Colombia (AUC). As of 2002, both received part of their financing, perhaps much of it, from drug operations. They controlled lands that were used for the cultivation and manufacture of cocaine and heroin. The profits from those drugs amply financed the revolutionary groups. The government's troops constituted a third force of violence in the nation, although their task was to control or eliminate the revolutionaries.

Press Laws

Article 20 of the Colombian Constitution stipulated a series of guarantees regarding freedom of the press. It guaranteed freedom of expression as well as freedom for journalists to carry on their work. It also guaranteed the right of individuals to begin media companies and the right of journalists to keep their sources secret. The constitution promised to protect journalists. It set up a complicated body to monitor and defend press freedom with elected persons representing the media who must have experience in the media professions. The group had to be representative of the wide range of media—newspapers, radio and television, public, for profit and non-profit, regional, and national. Pierce wrote that Colombia had greater press freedom than any of its Latin neighbors. That tradition continued through decades of conflict that the nation faced and periods of insurrections which occurred toward the end of the twentieth century.

The World Bank reported that the nation's "Colombia Portal," a plan for increasing information available to the public and providing for ready access to information about the nation, made a strong commitment to open information on purchasing, budgets, and planning. Part of the commitment was the establishment of Web sites for the Colombian government and all its agencies, making them available through the Internet. All government regulations since 1900 were to be accessible on the government Web site.

Human Rights Watch generally agreed that the Colombian press was free. It stated that the media are generally free of legal restrictions by the government. It noted, however, that some laws under the penal code and anti-corruption laws prohibited the publication of some kinds of information connected to criminal investigations. Pervasive interior conflict made these laws necessary.

For a time, Colombia had government requirements for professional journalists. The Law of the Journalist required new entrants into journalism to have university degrees. Continuing journalists were "grandfathered" into the professon. However, those laws were abolished in 1998.

Censorship

Even though as of 2002 no theoretical restrictions on press freedom or official censorship existed in Colombia, practical aspects media work led to the kinds of self-censorship that actually constituted restrictions. Dirnbacher reported that in the 1980s investigative reporting increased sharply. That was an understandable development in a nation torn by revolutionaries, guerillas, and government troops accused of human rights violations. But there was also a tendency toward other kinds of crimes in some segments of the society. She noted that El Espectador reported on secret financial deals involving Colombian banks. The banks withdrew their advertising from the newspaper, throwing it into financial crisis, she reported.

Attitudes Towards Foreign Media

In the early 2000s, illegal factions in Colombia were hostile to foreign media. However, official media outlets in the country associated heavily with international and regional organizations and sometimes provided leadership to them. For example, Colombia was a member of the InterAmerican Press Association. Moreover, U.S. media such as Time and Newsweek were popular in the nation, and many exchanges of all kinds took place between Colombia and the United States, the primary non-Latin American foreign nation with which it deals. Still, journalists were targets of hostile acts, including kidnapping and murder by rebel groups. Clearly, foreign and local journalists who become deeply involved in reporting on violent groups could be threatened by those groups.

Violence Against Journalists

In the early 2000s, the major news stories about Colombia dealt with its descent into chaos and violence. Connected to issues of press freedom, much of the violence was directed against journalists. As a result of a series of violence events, the president issued presidential decree 1592 which created in 2000 the Program for the Protection of Journalists.

According to Colombia Policy Briefs, 11 journalists were killed in the midst of Colombia's armed conflicts in 2000. A total of 169 had been killed since 1977, according to the Colombian Committee for the Protection of Journalists. At least 15 journalists were kidnapped, and 13 left the country after receiving threats. Six more were killed between January 1 and July 11, 2001. Kidnapping and abductions were a widespread problem, a common tactic used by the revolutionary and anti-government guerilla groups.

Dirnbacher wrote about the murder of several journalists. A reporter for El Espectador was killed in 1998. He had been investigating connections between bullfighting and organized crime. A political reporter and professor in Cali was shot as he left his university in 1998. He had helped the National Police establish a FM news radio station. In that same year, a teacher and journalist who was news director of Radio Sur, a subsidiary of the National Radio Chain, was shot. He had alleged there was corruption among members of former municipal administrations.

In 1999, a journalist and satirist who served as a go-between for families of kidnap victims who were taken by left-wing groups was shot on the way to his radio station. In that year, the FARC group kidnapped seven journalists because, FARC said, they had not reported the truth about guerillas and paramilitary groups committing atrocities against farmers. Also that year a bomb exploded near the offices of the El Tiempo in Bogotá. A FARC member said the bomb was set because of an article in that newspaper about FARC's attacks on the oil industry.

The editor-in-chief of El Tiempo , Francisco Santos, had to leave Colombia in 2000 because of death threats issued against him, probably by FARC, probably a result of his leadership of an anti-kidnapping organization. Santos had been held hostage with other journalists in 1990 by Pablo Escobar, as a protest against government threats to extradite drug traffickers to the United States for prosecution.

News Agencies

As of 2002 Colombia had several news agencies, notably the CNTV, the Comision Nacional de Television, and ERBOL. The Associated Press also was active in Colombia as were other private news services, such as UPI and Reuters. Cox News Service had a long presence in Colombian journalism and in reporting about Colombia. The government also provided a news service.

Broadcast Media

In addition to newspapers, Colombia has extensive radio and television coverage. According to the Central Intelligence Agency, as of 2002, there were 21 million radios in the nation (155 radio sets per thousand people, according to the World Almanac and Book of Facts ). There were also 454 AM radio stations and 34 FM stations. In addition, there were 27 short-wave stations and 60 television stations. World Almanac and Book of Facts reported that there were 188 television sets per thousand.

These media outlets were served by a variety of government and private organizations. The agency responsible for regulating AM, FM, and television frequencies and regulations is the Comision de Regulacion de Telecommunicaciones (CRT). Other government broadcasting agencies, according to TV Radio World, were Inravision and the Ministerio de Comunicaciones (Ministry of Communications). In addition, television was served by the nation's National Television Broadcasting, Regional Television Broadcasting, and Satellite/Cable Television Networks. There was also a government organization, the Instituto Nacional de Radio y Television de Colombia, that operated several radio and TV stations on behalf of the government.

There were a number of national radio networks, the best known of which was a conglomerate, Caracol (Snail.) It consisted of several networks including a sports operation, salsa and rock music networks, and other programming units.

The Radio Cadena Nacional (National Radio Chain, RCN), which called itself La Radio of Colombia, included a love music stereo network, a sports programming

Generally, the broadcast media were covered by the same constitutional guarantees as the print media. However, the broadcast media could be taken over by government in emergency situations, a procedure that is similar to that followed for emergencies in the United States. The Colombian government may exercise the right to censor radio and television in times of emergency, especially those associated with violence.

Electronic News Media

The nation has a few Internet news providers that provide news only. However, many of the newspapers and some of the radio networks sponsor news sites that provide extensive coverage of news information from the Internet.

Education & TRAINING

As of 2002, Colombia had 20 institutions of higher education that offered study in periodismo (journalism). (A journalist is a periodista. ) "Social communication" programs offered much more than traditional journalism in their academic programs. They may teach advertising, public relations, media management, and electronic journalism as well as print.

Journalism education programs in Colombia were organized into the Association of Faculties of Social

Communication (what were usually called departments or schools in the United States are referred to as faculties in Colombia.) The Association, in turn, belongs to the Latin American Federation of Faculties of Social Communication.

In the early 2000s, the Colombian journalism faculties presented curricula spanning 10 semesters or five years of study. Content included theoretical and practical information that might be found in U.S. schools of journalism as well as other subject matter. The programs typically included field experiences, too.

There were associations of journalists in Colombia, in addition to those involved in journalism education. There was an effort in the 1970s to organize Colombian journalists in a labor union. However, Colombia did not have a member organization of the International Federation of Journalists, the international group that oversees and coordinates such efforts.

Summary

In the early 2000s Colombia was, in many ways, a nation of contrasts. That was especially true of its press and journalism. The press was essentially free from governmental interference and was also generally of high quality. That appeared to be true of both print and electronic media. It treated journalists as major figures and had presidents who came from the field of journalism. Its education of journalists was sophisticated and widespread.

However, Colombia was also a nation that was beset with internal conflicts. One of the results of those conflicts was the spread of the illegal drug trade, especially the production and distribution of cocaine. It was also a producer of heroin. Rebel groups were believed to finance themselves with proceeds from the production and distribution of drugs. The drug issue was further complicated by the economic deprivation experienced by many Colombians so many of whom lived in poverty. Growing the raw material for drugs and otherwise engaging in the drug trade was a route out of poverty for many economically disadvantaged Colombians.

The internal conflicts also involved journalists and press officials, some of whom were kidnapped or assassinated or who faced threats of such violence. Therefore, the press and journalism were difficult areas of employment in Colombia. Perhaps they were more dangerous in that nation than in any other.

Therefore, what may well be considered a high quality press industry was tempered by one of the world's most complex and unstable social environments—in which inordinate numbers of public facilities and the nation's infrastructure were subject to constant threat. In addition, numbers of people, including journalists, were kidnapped, murdered, and displaced by the activities of rebel groups. The violence facing Colombia, although warring parties and the factors in the violence might characterize the end of the twentieth century, was a part of Colombian life for a half century.

It was inadvisable to generalize about this nation of contrasts. In many ways, it was an inviting environment for press work while in others it posed dangers to those who worked in the field.

Significant Dates

- 1998: Andres Pastrana, former journalist and candidate of Conservative Party, is elected president of Colombia, begins negotiations with rebel groups to end violence, and establishes "control zones," where rebel groups are able to control territories they had conquered.

- 1998-1999: More journalists and other media personnel kidnapped, forced into exile, or murdered, and media facilities are bombed.

- 1998: Law of the Journalist terminated.

- 2002: FARC again bombs, kidnaps, and murders Colombians. President Pastrana announces that peace with rebel groups will not be achieved during his presidency. Álvaro Uribe Ve'lez elected president as an independent.

Bibliography

Allman, T. D. "Blowback." Rolling Stone, 9 May 2002.

"Colombia." Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). The World Factbook . Available from http://www.cia.gov .

"Colombia." Microsoft Encarta Online Deluxe Encyclopedia 2001. (3 Apr. 2002). Available from http://encarta.msn.com .

Contreras, Joseph. "Colombia's Hard Right." Newsweek International, March 25, 2002. Available from www.msnbc.com/news .

Defensoria del Pueblo Colombia report. Available from http://www.colombiapolicy.org .

Dirnbacher, Elizabeth. Journalism in Colombia. Available from http://www.Freemedia.at/journali.htm , 2000.

Famighetti, Robert. The 1999 World Almanac and Book of Facts. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1999.

Ferriss, Susan. "Colombians Elect President amid Violence." The Colombia State. (May 27, 2002): A7.

Forero, Juan. "Colombia Voters are Angry, and Rebels May Pay Price." The New York Times. (May 26, 2002):4.

Guillermoprieto, Alma. "Letter from Colombia: Waiting for War." The New Yorker. (May 13, 2002): 46-55.

Human Rights Watch. Available from http://www.Hrw.org/americas/colombia/ .

International Year Book: The Encyclopedia of the Newspaper Industry, 2001. New York: Editor and Publisher, 2001. Available from http://www.editorandpublisher.com .

Library of Congress, Federal Research Division. Colombia Country Studies, Area Handbook Series.

Marquis, Christopher. "The U.S. Struggle to Battle Drugs, Just Drugs, in Colombia." The New York Times. (May 26, 2002): wk 7.

Pierce, Robert N. "Colombia." World Press Encyclopedia. New York: Facts On File.

"Two Bombs Explode in Colombian City." The Colombia State. (April 8, 2002): 3A.

U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. Colombia Country Reports, Human Rights Practices for 1996, January 30, 1997.

WWW.Virtuallibrary : Latin America Resources. Available from www.etown.edu/vl/latamer.html

TVRadioWorld. Available at http://www.tvradioworld.com

Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Available from http://www.wikipedia.com .

World Development Indicators database, July 2000. Available at www.colombiapolicy.org .

Leon Ginsberg