El Salvador

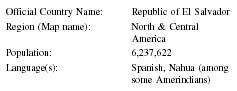

Basic Data

| Official Country Name: | Republic of El Salvador |

| Region (Map name): | North & Central America |

| Population: | 6,237,622 |

| Language(s): | Spanish, Nahua (among some Amerindians) |

| Literacy rate: | 71.5% |

| Area: | 21,040 sq km |

| GDP: | 13,211 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Television Stations: | 5 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 600,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 96.2 |

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 35,000 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 5.6 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 91 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 2,750,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 440.9 |

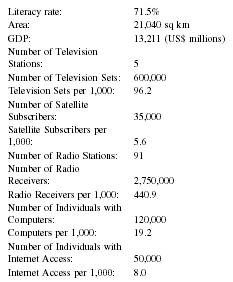

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 120,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 19.2 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 50,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 8.0 |

Background & General Characteristics

El Salvador had an estimated population as of 2002 of over 6 million, a higher population density than India, and a gross national product (GNP) of US$938 per capita. The country experienced a terrible civil war during the 1980s and the early 1990s; endured death squads that killed human rights advocates; felt population pressures; and survived earthquakes, hurricane Mitch, and the denigration of the natural environment. El Salvador has several political parties: the old moderate, center-left Christian Democratic Party (PDC); the right wing Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA); and the old guerilla, now leftist Farabundo Marti para la Liberación Nacional (FMLN). Through 1988, the PDC kept the presidency but the ARENA subsequently held on despite strong competition from FMLM. The Inter-American Development Bank spent millions of dollars in projects relating to health issues from the earthquakes, supported social peace, citizen security, and peaceful coexistence of political parties in El Salvador, and attempted to get at the root of these problems in dealing with massive poverty, homelessness, vagrant youths, and serious health issues. President Francisco Flores, unable to stop the terrorist kidnappings even in the midst of the national emergency of the earthquakes, was successful in gaining more freedom to criticize the government and sought both emergency and long-term planning initiatives in an attempt to establish social and economic stability.

El Diario de Hoy and La Prensa Gráfica were the leading daily newspapers of El Salvador. In the late 1990s their publishers allowed unheard of freedom of speech to the El Salvadorean reporters whose investigative journalism both stretched the traditional freedom of reporting and sold newspapers. Conservative media owners lamented the fading of the absolute dominance of the right-wing ARENA which won almost all elections from the end of the 1992 civil war until the beginning of the millennium and held on to the presidency in the last election only through a coincidence of events and candidates.

Economic Framework

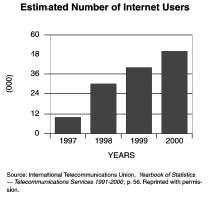

The working conditions of reporters improved in the late 1990s, although salaries continued to be so low that journalists were vulnerable to bribery. Even among information workers, new technologies were not always available. However, on February 18, 1998, the Inter-American Development Bank approved a US$73.2 million loan to El Salvador for expanding video libraries, interactive radio, learning resource centers for new technologies, school equipment, and computers through the ministry of education. However, even in 2002 El Salvador was a land of extremes. A suite in the Hotel Presidente, headquarters for the 1994 presidential elections, cost US$500, while a civil servant made US$4 a day and had no protection from being thrown out of his job in the next election. Luxury juxtaposed uncollected garbage, and black water filled the streets of the towns of El Salvador. According to the CIA World Factbook , there were 380,000 telephone lines (1998); 40,163 cellular phones (1970); 61 AM and 30 FM Radio stations (1998); 1 Intelsat (Atlantic Ocean) satellite (1997); 2.75 million radios (1997); 600,000 televisions (1990); 5 television stations (2000); 4 Internet service providers (2000); and 40,000 Internet users (2000).

Press Laws

Article 243 of the Constitution prohibited the national police from allowing detained people to talk to journalists because "it affects their good names and violates their right to due process." Article 272 of the El Salvadoran law stated that "In general, penal proceedings will be public. However, the judge may order a partial or total press blackout when he deems, for valid reasons, that it is in the interest of good morals, public interest or national security, or is authorized in some specific rule." This blackout may be partial or complete. Article 273 stated that "Hearings will be public, but the court may, on its own authority, order or at the request of one of the parties that said hearings be closed when required for reasons of good morals, public interest, national security or it is authorized by some specific rule."

In September, 1996, the ARENA party pushed through a controversial bill which was the New Telecommunications Law of El Salvador. Unfortunately, although the legislature had a law that built the legal framework for democratic freedom of speech and of the press in telecommunications, major sections were excluded from the bill which actually was passed. Even the newspaper, Diario de Hoy , an old mouthpiece for the conservative party, admitted that the new law hurt progress towards freedom of expression and suggested that this would make the radio the only place where journalists might be free to tell the truth. This form of the telecommunications law was presented to the legislature by the Commission for Economy and Agriculture. Through a simple majority, largely of ARENA deputies, the law passed, although the representatives of the opposition parties protested and left the Assembly. The great losers were the Association of Participating Radios and Programs of El Salvador (ARPAS) and the Union of Technical Workers of Telecommunications Business of El Salvador (ATTES). These organizations had written proposals in hopes that they might be incorporated into the law and then lobbied for those proposals and their basic regulations and guarantees that the public, as well as the private, sector would be represented. ARPAS had consulted the Federal Communications Commission of the United States in making their suggestions, but nothing of their proposal was included. ARENA's law only needed the signature of then president Dr. Armando Calderon Sol, himself of the ARENA party.

In July 2000, El Diario de Hoy and La Prensa Gráfica detailed a government scandal in which government legislators were spending excessively on food, travel, and entertainment. In reaction to the news stories, the executive committee of the Legislative Assembly for a time restricted public access to any information concerning its administration and budgetary records. Since there was no member of the FMLN on the executive committee, the press coverage of the scandal could suggest that the young investigative reporters on these two periodicals were no longer afraid to report such news and the publishers were willing to sell newspapers on the basis of such reports and to back their investigative reporters.

While legislation brought forth by the Association de Periodistas de El Salvador to protect press sources languished in committee, never passing in the legislative assembly, at least the Asociacion de Periodistas de El Salvador continued to thrive. Contraportada, unable to secure any significant funding, all but ceased to exist. El Salvadorans had limited public access to their own government documents. Article one of the General Law of the Creation of SIGET (Superintendencia General de Electricidad y Telecommunicaciones), gave it total autonomy on all administrative and financial aspects. Article 2 required that SIGET be located in San Salvador with offices established in other locations in the country. Article 3 had it relating to other government organizations through the Ministry of Economics. Section 5 dealt with registering telecommunications stations, a big issue in El Salvador.

Censorship

For many years, journalists were controlled either by the dictates of conservative publishers or by fear of the retribution of El Salvadoran security forces. In August 1988, Harper's editor Francisco Goldman published a review of the Central American press that was quoted by Noam Chomsky in "Necessary Illusions": "You have to be rich to own a newspaper, and on the right politically to survive the experience. Papers in El Salvador don't have to be censored: poverty and deadly fear do the job." Fortunately, this sad state of affairs was no longer absolutely true in the early 2000s. While once the military and government were above printed criticism unless they had fallen into government disfavor and might be sacrificed to the press in the name of spin, in the 2000s investigative journalism did occasionally peek out from among the many pages devoted to reporting sports scores, advertising smart clothes, parading new brides, and making social announcements.

The 1962 El Salvadoran Constitution, Article 6, granted freedom of speech, expression, and information that would not "subvert the public order, nor injure the morals, honor, or private life of others." For the last 20 years of the twentieth century, there was a mockery of these guarantees. However, after 1982, with the installation of a democratic system of elected officials and, at last, a decline in kidnappings and violent political retaliation and politically motivated killings, fear of reporting the news in either the press or in the broadcast media began to lessen. The 1983 Constitution confirmed the rights written down in the 1962 version. Nonetheless, conservative repression, as well as the violence of the opposing left-wing terrorists groups against the press in the early 1980s, made for a kind of self-censorship. Broadcasting licenses were and continued to be sought and renewed on a regular basis. This requirement, so harmless elsewhere, functioned as a kind of censorship for radio and TV stations as there was no guarantee of the renewal of licenses. Most of the owners of the larger broadcasting stations, periodicals, and magazines were conservative so the owners of these information sources became de facto censors and tended to move their periodicals into a conservative camp. Fear of the ubiquitous violence in El Salvador during the 1980s and 1990s, however, caused both extreme right and left wing groups to censor themselves. Despite the need to gain broadcast licenses, owners of broadcast media tolerated greater freedom of speech than did the newspapers, where the editorial policies reflected the opinions of the editors and publishers and therefore often deviated from the realities of the events discussed.

Political parties, businesses, unions, individuals, and even government agencies, might express their opinions through the campos pagados (paid political advertisements) accepted by most newspapers as advertisements. Campos pagados had been one of the few means of access to the printed word available to once revolutionary leftist groups such as the FMLN-FDR, but, of course, any organization or individual had to pay the cost for this access to the public. With the victory of FMLN in the March 12, 2000 elections, censorship decreased in some ways. However, in a famous example of censorship, Juan Jose Dalton, the son of revolutionary writer Roque Dalton, lost his place on the editorial board of El Diario de Hoy and resigned from the paper during the election campaign after he published a piece that sharply rebuked ARENA, the fading but still strong, right-wing National Republican Alliance.

State-Press Relations

While once the state controlled the press but not the radio, as of 2002 there was a more militantly adversarial relationship between state and press and perhaps a less adversarial relationship between the two in broadcast journalism. There was a time in the 1980s when a broadcast journalist without a license would have been considered a rebel and simply shot in some parts of the country and one could largely assume that daily newspapers sought government funding and defended government decisions while radio was the medium of the people. That, to a certain extent, changed. As of 2002 even reporters on La Prenza and El Mondo occasionally stood up to government privilege and survived the experience. However, El Salvador's journalists continued to suffer from restricted access to public records and resources. These restrictions limited their ability to legally contend for this information. The penal code allowed police officers to deny the press information about who had been arrested or even to prevent reporters' access to courtroom trials. Article 339 of the El Salvadorian penal code allowed imprisoning journalists for up to three years for falsely accusing someone of a crime: "An individual who offends the honor or dignity, by deed or word, of a public official in the performance of his duties, or threatened such an official verbally or in writing, shall be punished with a prison term of six months to three years. The punishment may be increased by one third of the maximum sentence should the offended party be the President or Vice President of the Republic, a Deputy of the Legislative Assembly, a Minister or Deputy Minister, a judge of the Supreme Court or Court of Appeals, a trial judge, or a justice of the peace."

Unfortunately, this law was not just a threat in El Salvador. Former vice president of El Salvador, Francisco Merino of the PCN (Parotid de Conciliacion Nacional), invoked this law when he brought legal action against five journalists for insulting him even though he had been arrested for shooting a police officer. Four reporters from La Prensa Gráfica , Mauricio Bolanos, Alfredo Herandez, Gregoria Moran and Jose Zometa, and El Mondo 's Camilia Calles were all threatened with the same sort of legal action as they pursued their investigative reporting of Merino's alleged illegal transfers of property as it was being investigated and brought before Judge Ana Marina Guzman.

In perhaps a breakthrough change of editorial policy, on September 1996 El Diario de Hoy , traditionally the conservative supporting newspaper of the ARENA party, criticized the new Telecommunications Law passed in El Salvador against the wishes of almost every other party in El Salvador.

Attitude Toward Foreign Media

For years, rebel forces included propaganda teams and actively enlisted often poorly trained journalists, media specialists, radio operators, and technicians. Particularly in rebel territory a person caught with radio equipment would be shot. Kidnapping was rampant during the civil war and not unknown even as of 2002 as a form of income. Foreign journalists were as likely as not to be rebels who had little formal training in radio broadcasting but gained fame through the bravery of their forbidden, unlicensed broadcasting.

Journalism continued to be a dangerous occupation in El Salvador, particularly if the journalist worked for a moderate newspaper or a television or radio station. According to a July 2000 Reuters press release from London, Jorge Zedán, 60-year-old co-owner of the television station Canal 12, and one of the directors of Saltel, the telecommunications firm, was kidnapped, held for five days, and released only after a ransom was paid. The police reportedly attacked Edwin Gongora and Miguel Gonzalez, also of Canal 12, and Ernesto Rivas of El Diariode Hoy, beat them up, and destroyed their equipment in order to stop them from interviewing Roberto Mathies Hill, who was detained and accused of fraud. The only death associated with journalism of late was the 1997 unsolved murder of Maria Lorena Saravia, a newsreader for Radio Corporacion Salvadorena. This single death was a far cry from the murders of over 25 journalists who were killed during the civil war. One could only hope that the relative safety of journalists at the turn of the millennium would be maintained. To put things in perspective, since 1992 and the end of the civil war, there was a post-war crime wave in which murderers generally got away with murder. Of 6,792 homicides since the war ended, only 415 suspects were arrested, and La Prenza Gráfica re-ported on April 21, 1999 in "Justicia de El Salvador reprobada" that the Salvadoran Foundation for Economic and Social Development (FUSADES) claimed that suspects were arrested in only 6 to 8 percent of murder cases (Popkin).

News Agencies

El Diario de Hoy , the conservative full-service newspaper, also had a daily Internet presence and had worked hard in the late 1990s to rid itself of its reputation as a conservative mouthpiece of the government. In reaction to its reputation for being willing to present false news, the paper attempted to change the impression it has given the people of El Salvador. On June 3, 2002, for example, the Internet daily edition of this newspaper ran the picture of a Morazean farm worker on the cover as if to suggest that its old adversarial relationship with the leftist territories had disappeared. El Diario de Hoy had sections on sports, business, international and national news, and even a section called "Do You Want to Invest in El Salvador?"

Diario El Mundo offered a daily Internet news service at ElMundo.com.SV with an amazing "ultima hora" service designed to compete with the swiftness of radio news, in that national and international news appeared there in less than two hours.

CoLatino or El Diario CoLatino claimed to be a completely independent newspaper that had news which was real, truthful or "actualidad," but one had to get through the first page of sports before reaching news articles. CoLatino 's claim that the news was real suggested that El Salvadorans had been the victims of so much misinformation in newspapers that they continued not to trust the medium as they did radio.

La Prensa Gráfica , the premier moderate newspaper, had an extensive Web site which made news available daily on the Web as well as to those who subscribed for or bought the paper. Its subhead was "Noticias de Verdad" which, of course, implied that it was different from other newspapers in that its news was true. Its Web site was divided into national, international, department, economic news, features, and sports. El Heraldo de Occidenteand El Heraldo de Oriente , news from the west and east, kept those interested in local events abreast of the news and made La Prensa Gráfica appear open and fair-minded about local issues. Margaret Popkin noted that a major factor "that contributed to creating a climate of reform was an editorial change at La Prensa Gráfica … This traditionally conservative daily took up an editorial line that favored the peace process and judicial reform effort … the need for fundamental reforms and … protecting individual rights" (221). The policy change was attributed to David Escobar Galinda, university president, utopian, and deservedly famous poet.

Also worth mentioning were the following sources of news: El Noticero , from Chanel 6; Guanaquiemos an electronic magazine, published in Miami, Florida by Mrs. Cecelia Medina Figueroa; Central American News , Salvadoran section; El Faro , a news service which offered up-to-date web reports on news, sports, letters to the editor, and music and which archived old articles; Diario Oficial , the official dissemination organ for legislative decrees. They were made available by the El Salvadorean government and published in this journal.

Broadcast Media

Radio

In the capitol of El Salvador, 70 radio stations compete for advertisers. Since El Salvador is small and uses repeater stations, virtually all 103 commercial radio stations can be heard in every part of the country. There is only one government-owned broadcast station. Because broadcast media does not suffer from the handicaps of illiteracy or costly access to the public, radio is the most widely used political medium in El Salvador. The ratio of radios to television sets certainly changed in the late twentieth century. In 1985 there were an estimated 2 million radio receivers and only 350,000 TVs in the whole nation. Radio Cabal broadcasted programs of news, debate, political interest, information, and radio dramas aimed at the poor of San Salvador, but since it was linked with left-wing politics, even though it was not associated with any political party, the station had difficulty getting advertisers. Obviously, targeting the poor parts of the population limited its utility to advertisers. Radio Cabal had depended on donations from international sources, including Denmark to cover broadcasting expenses. Mellemfolkeligt Samvirke (MS), the Danish Association for International Cooperation, and Danida, the Danish International Development Agency supporting communication for development, backed the radio station both financially and with volunteers since the station's establishment in 1993.

Two of FMLN's groups, Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo (ERP) and Fuerzas Populares de Liberacion (FPL), operated so-called clandestine stations named Radio Venceremos and Radio Farabundo Marti, respectively. ( CIA Book of Facts , Mass Media). Of course both the openly operated station and the once secret station served as sources of information for and propaganda from the FMLN. Most of the smaller stations focused programming on music rather than politics and news, but after the mid 1980s, the news programming of smaller radio stations presented a range of political points of view including rebel material, music which had potentially leftist themes, and propaganda and news reporting. The very active amateur radio association of El Salvador is Club de Radio Aficionados del El Salvador. The radio broadcasting organization of Asocacion Salvadorena de Empresarios de Radiodifusion (ASDER) is the largest in the country. VOXFM, PulsarFM, La Femenina, LAMIL80, Radio Renacer, Radio Nacional, LaQue Buena all have Web presences that allowed them to reach El Salvadorans in the United States.

The position of radio in 2002 was partly caused by the end of the civil war, but events surrounding the legitimacy of radio stations attested to the fact that all civil strife did not cease in 1992. Many years of civil war were succeeded by the 1992 peace agreement between the left-wing guerilla FMLN and the military-supported rule, and in 1994 the peace agreement led to a truly democratic general election with, for the first time, a broad spectrum of parties participating in the election. In a dramatic contrast to the election, on December 4, 1995, the Salvadoran National Civic Police (PNC) closed 10 radio stations and confiscated their broadcasting equipment. These stations were all members of the Association of Participatory Radio Stations and Programs (ARPAS) and the World Association of Community Radio Broadcasters (AMARC). Juan Jose Domenech, president of ANTEL, the state agency with the responsibility of regulating broadcasting and telecommunications, gave the orders to close the following stations: Segundo Montes (Meanguera, Department of Morazan), Izcanal (Nueva Grenada, Usulatan), Ulua (Cacaopera, Morazan); Cooperativa (Santa Elena, Usulatan); Victoria (Villa Victoria, Cabanüas); Suchitlan (Suchitoto, Cuscatlan), Excel (Zaragoza, La Libertad), Teo-Radio (Teotepeque, La Libertad), and Nejapa (Nejapa, San Salvador). Radio Sumpul might have been closed but in Guarjila, department of Chalatenango, citizens supposedly successfully defended the station from police action. The zona oriental, Morazon, the home of Radio Venceremos, continued to be a stronghold of extreme political activity. Some of the radio stations there still announced revolutionary causes, espoused what would be considered extreme priorities of redistribution of land, and remained faithful to the old cold war adversarial stance.

Television

As of 2002, there are 8 television channels, 8 commercial stations, and 2 government-owned stations that presented educational programming during limited broadcasting hours. Perhaps more than any other medium, television had increased freedom of speech and access to information, as well as the opinions of a diversity of political organizations. TV news crews covered events, attended press conferences, interviewed, investigated, and reported elections results. When the military, police, and security forces were accused of human rights abuses, TV crews covered these stories and interviewed those accused.

Although, like Salvadorean radio, Salvadorean television stations could transmit over the entire small country,

Associations important in this field are as follows. ANTEL was the state agency responsible for regulating broadcasting and telecommunications. Juan Jose Dome-nech was president of ANTEL and controlled the licensing system. Superintendencia de Electricidad y Telecommunicaciones (SIGET), supervised and controlled telecommunications media in El Salvador. And AMARC which covers community broadcasters.

Electronic News Media

As of 2002, providers of Internet services in El Salvador with their own Web pages were as follows: Americatel, www.americaltel.com.siv ; CyTec, www.cytec.com.sv ; EBNet www.gbm,net ; IFX, www.ifxnetworks.com ; Integra, www.integra.com.sv ; Intercom, www.intercom.com ; Internet Gratis, www.internetgratis.com.siv ; Netcom, www.salnet.net ; Saltel; www.saltel.com ; Telecam, www.telecam.net ; Telecom, www.navegante.com.sav ; Telefonica, www.telefonica . com; Telemovil, www.telemovil.com ; Tutopia, www.tutopia.com . Providers of Internet sources without Web sites or who may be working on their Internet presence at publication time are: AmNet; EJJE; El Salvador on Line; and Newcom. Companies like Genesis Technologies are certified to install and support Internet lines and construct Intranets in El Salvador. Internet de Telemovil and many other companies are involved in webhosting. Cybergate and Intersal SA de CV also were Web providers.

Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnologia (CONACYT) was publishing Rusta El Salvador Ciencia y Tecnologia for two years about the turn of the century, and the contents of this publication were available on the Web. From 1997 to 1999 Conacyt published Boletenes del CI. Those editions were still available as of 2002 on the Web as archived material.

Proceso , a weekly news bulletin from El Salvador, was published by Center for Information, Documentation (CIDAI) and Research Support of the Central American University (UCA) of El Salvador where it could be read on the university Web page, scripted into Spanish but partially or extensively obtained in English on PeaceNet. CIDAI was an impressive news service that covered political events and archived all its editions so that every issue was readily available. There were many articles relating to El Salvadoran immigrants in the United States and one of the group that might benefit from this Internet weekly news service that is uninterrupted by either advertising, sports or fashions. As of 2002, Proceso had written an editorial suggesting a reason why President Bush admired President Flores: President Flores was docile to the military objectives of the United States and had defended the war on terrorism and the installation of an American monitoring base on Salvadoran ground. The political events were presented in depth with serious academic and intellectual content often not found in other news coverage, and the editor seemed to support absolute freedom of speech.

Internet en El Salvador (SVNet) was a limited search engine set up by an act of the constitution of El Salvador on September 2, 1994, and run by a Secretariat associated with CONACYT. Phase I connected CONACYT, ANTEL, VES, Don Barco, and UCA. Phase II claimed to be adding VES San Miguel and Santa Ana, the National Library, EUSADES, and Polytechnic University. Telecam operated telecommunication services supervised by SIGET. Moreover, Telecom ran the telephone system and one of its subsidiaries, Publicar, S.A. published the yellow pages and distributed them door to door. Finally, computer magazines, El Salvador USA. El Salvador Magazine. comand Revista Probidad claimed to be non-partisan, anti-corruption, and pro-democracy.

Education & TRAINING

There is little doubt but that El Salvador has had an increasingly professional group of print and broadcast journalists. However, under investment in education, a damaged infrastructure, relatively weak professional institutions, a legal system historically unfriendly to investigative journalism, very low salaries in the profession, and a degraded physical environment all slowed reconstruction and the stabilization of El Salvador's many communications channels and periodicals. In some ways El Salvador's universities were overwhelmed by the nation's large number of people under the age of 20. The universities did not have a sufficiently organized professional curriculum that included journalism, radio and television, and computer science. However, the technological universities, such as Universidad Politecnica de El Salvador (VPES) and the Universidad Tecnologica de El Salvador, were making rapid advances in the area of telecommunications. The University of El Salvador offered both a master's and a 5-year Licenciatura in Journalism with an extremely well organized plan of study through the faculty of Science and Humanities. Extensive and professional course work in newspaper writing, radio and TV was available. The University of El Salvador had a department of periodismo (journalism) and was dedicated to creating professionals in the area of communication.

Summary

As of 2002, the media professionals in El Salvador, of necessity, had a kind of largely unspoken wait-and-see policy regarding political reform and freedom of speech. The FMLN evolved from being a guerilla army into an important political party, winning on March 12, 2000, a plurality in the legislative assembly as well as re-electing the FMLN candidate for mayor of San Salvador. Ironically, Cuba's insistence on leftist unity and that of Socialist European sponsors such as the West Germans, lessened the numbers of the dead, yet the fact remained that over 50,000 people died between the Duarte death squads and the leftist juggling for power. In the early 2000s, understandably, the desire for order and stability was great. Although the traditional El Salvadorean media were not as closely censored and restricted as Nicaraguan media, neither did they illustrate the diversity, plurality, and freedoms of the press of Costa Rica. Enjoying moderate freedom of speech and exhibiting great differences in political points of view, the press of El Salvador was self-censored. Publishers feared la violencia of those who would disagree with their interpretation of the news, whether opponents were right or left-wing organizations or political parties and groups. The largely conservative, business-oriented owners of the press caused a less conservative broadcast network to be the place that many El Salvadorians found news. Literacy was as much a factor in the popularity of broadcast news as the more liberal reporting provided by broadcasters. Even though approximately 70 percent of the adult population was reported to be literate, in the capital the press's influence was still limited by considerable illiteracy and poverty.

Economic censorship was real in the often under-capitalized organizations that published newspapers and ran broadcast stations. An example of the kind of economic censorship that occurs is as follows. In June 2000, after a phone-tapping accusation by Jorge Zedán, co-owner of TV DOCE, he was kidnapped but then released. El Diario de Hoy published a story accusing the state telephone company of tapping a huge number of phone lines, including the phone of Lafitte Fernandez, managing editor of that newspaper and by publishing the story accused a major advertiser and revenue source, France Telecom, of criminal activity. France Telecom immediately canceled its advertising in El Diario de Hoy. In 2002, it was too soon to suggest that all was well between the media and the government in El Salvador.

Time will tell if the government really does encourage telecommunications and sophisticated broadcast networks in and around Morazon, the old rebel capitol, and how the government uses this new technology. Nonetheless, despite significant destruction from guerrilla sabotage in the 1980s, earthquakes, and terrible economic problems, El Salvador experienced significant growth in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1990s. Powerful forces helped El Salvador restore order. The media's unrelenting pursuit of the truth, actualidad , gave one cause for hope for greater freedom of the press, clearer legal relationships between government and the press, and a more stable financial future for the media of El Salvador.

Significant Dates

- 1995: Confiscating their equipment, national police close 10 community radio stations that never received broadcast licenses from ANTEL but were members of the AMARC and had been operating since at least 1990.

- 1996: ARENA is able to get their Telecommunications Law passed in the Salvadorean legislature despite bills introduced by other parties and offers by telecommunication networks that are more forward-looking than ARENA's. Even El Diario de Hoy , usually supportive of ARENA, concedes that this bill damages freedom of expression.

- 1997: Maria Lorena Saravia, a news reader from Radio Corporation Salvadorena who also works for YSKL and canal 21 television, is murdered. The crime remains unsolved.

- 1999: Francisco "Paco" Flores of the Arena party begins his five-year term as president of El Salvador. The FMLN's candidate, with 29 percent of the vote, fails to disassociate himself from the violence of the civil war. Flores has spent those years teaching philosophy and managing an irrigation project with his wife, a schoolteacher. Flores, a former president of El Salvador's unicameral National Assembly, runs as a new kind of leader of ARENA, the traditionally conservative party. Flores was educated at Amherst, MA, and studies at Harvard in Cambridge, MA, and at Oxford University in England.

Bibliography

Arreaza-Camero, Emperatriz Communicacion. Derechos Humanos y Democracia: El Rol de Radio Venceremos en el Proceso de Democeatizacion en El Salvador (1981-1994). Available from http://lanic.utexas.edu/project/lasa95/arreazal.html .

Belt, Juan. A.B. and Anabella Larde de Palomo. "El Salvador: Transition Towards Peace and Participatory Development." Paris: unpublished paper presented at OECD workshop 21 November 1994.

Chomsky, Noam. "Necessary Illusions: Sad Tales of La Libertad de Prensa." Harper's , (August 1988). Available from http://zena.secureforum/znet/chomsky/ni/ni/c10-s25html .

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). World Factbook 2001. Available from http://www.cia.gov .

"El Salvador, Rural Development Strategy." Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Galeas, Marvin. "La prensa como contrapoder." Tendencias, no. 40. San Salvador: COOPEX.S.A., May 1995.

Gonzalez-Vega, Claudio. "BASIS—Central American Reconnaissance Mission Report 19-24." Prepared for the Consortium for Applied Research on Market Access (CARMA), May 1997.

Haggarty, Richard A., ed. El Salvador: A Country Study. Washington D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress, 1990.

Morales, Maria. Radio Venceremos: un medio de comunicacion alternativo en Latino America. Mexico: U.N. A. M. (Tesis mimeografiada), 1992.

Popkin, Margaret. Peace Without Justice: Obstacles to Building the Rule of Law in El Salvador. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University, 2000.

Merrilee Cunningham

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: