France

Basic Data

| Official Country Name: | French Republic |

| Region (Map name): | Europe |

| Population: | 59,551,227 |

| Language(s): | French, rapidly declining regional dialects and languages |

| Literacy rate: | 99.0% |

| Area: | 547,030 sq km |

| GDP: | 1,294,246 (US$ |

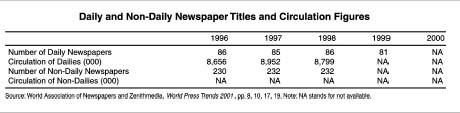

| Number of Daily Newspapers: | 86 |

| Total Circulation: | 8,799,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 190 |

| Newspaper Consumption (minutes per day): | 30 |

| Total Newspaper Ad Receipts: | 1,784 (Euro millions) |

| As % of All Ad Expenditures: | 17.70 |

| Number of Television Stations: | 584 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 24,800,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 416.4 |

| Television Consumption (minutes per day): | 193 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 2,662,280 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 45.2 |

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 4,300,000 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 72.2 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 55,300,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 928.6 |

| Radio Consumption (minutes per day): | 191 |

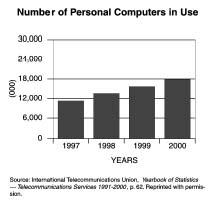

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 17,920,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 300.9 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 8,500,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 142.7 |

Background & General Characteristics

General Description

National daily press is no longer the prime information source for French people. It accounts for two percent of the titles and 14 percent of the circulation. Magazines account for 40 percent of the titles and 38 percent of the circulation. Technical or professional press leads the number of titles, 44 percent, but only accounts for five percent of the readership. The true leader in readership is the regional daily and weekly press, with 43 percent, although they only have 14 percent of the publications. French people overwhelmingly rely on magazines and on their local daily newspaper for news. In 2000, more French people read the sports daily L'Equipe and consulted TV guides than read the prestigious Le Monde . The technical and professional information press, while extremely diversified, has a very small audience. The number of new publications reflects this trend: in 1998, 427 new titles were created, among which 250 magazines and 140 technical and professional information press titles. The regional press is the most prominent media, ahead of television.

The national press remains an important segment of the industry even though it is heavily centered in Paris. The daily opinion press has practically disappeared, with main newspapers adopting a more neutral tone and limiting political commentaries to editorial articles and op-ed pages. The remaining opinion newspapers are La Lettre de la Nation (RPR), L'Humanité , which today remains the voice of the communist party, the ultra-rightist Présent , and the Catholic La Croix . The daily information press's most important titles are Le Monde , Le Figaro and Libération . Their influence is felt on domestic public opinion and in the other media. The most prominent popular daily newspaper is Le Parisien-Aujourd'hui , one of the few to have adopted a regional press strategy. France-Soir, another popular newspaper, lost two-thirds of its readership between 1985 and 1997, plummeting to 173,000, and survived only by adopting a tabloid format in 1998. Theme daily newspapers, by contrast, have an increasing success: the financial and economic newspapers Les Echos , and La Tribune , with the sports newspaper L'Equipe being the first daily newspaper. In 1993, the street press appeared; Macadam-Journal , La RueSans-Abri, and L'Itinérant , weekly or monthly publications of the homeless and the unemployed, promoted their copies at train stations and in the metro. Today, their circulation is declining.

The Nature of the Audience

In 2000, 18.3 percent of French people above age 15 read a national daily newspaper every day, against 38.4 percent for the regional or departmental daily press and 11 percent for the regional daily press and 95.9 percent for the magazine press. Overall approximately half the French population over 15 years of age read a regional newspaper regularly, with readership distributed equally between men and women. While the regional press reaches only 17 percent of the public in the greater Paris area, it reaches over 50 percent of the public in the provinces.

One third of all readers of the national daily press are found in the Paris region. They belong to the educated upper middle classes; 61 percent of them are actively employed men; one third of the readers are under 35 and two-thirds under 50 years of age. Readers spend an average of 31 minutes reading the newspaper, and 70 percent read the newspapers before 2 p.m.

Readers of the daily regional or departmental press are evenly distributed between men and women, with approximately 25 percent under 35, 41 percent between the ages of 35 and 59, and 33 percent over 60. Fifty-one percent were actively employed (27 percent in rural towns, 30 percent in large cities). Parisians represent 7.4 percent of this readership. Readers spend an average 24 minutes reading the regional newspapers.

The readers of the weekly regional press are the most faithful and exclusive of all readers. Thirty percent of readers are under 35, while 60 percent are under 50, and 58 percent are actively employed. Readership is distributed evenly between men and women. Readers belong to all socio-professional categories, with employees, workers, and farmers being the main groups.

Press readers have progressively gotten older, forcing the press to adopt new strategies to attract young readers, such as putting newspapers in the schools, improving the distribution system, and creating magazines especially for young readers. The magazine press in general is faring extremely well. French people read an average 7.5 magazines, mostly in their homes. Some 92 percent of young people read magazines, half of them regularly. Increases in television viewing time and universal radio listening have also cut into the press reader-ship. Finally, the internet press has gotten a share of the market. The average press budget per household is US$132.

Quality of Journalism: General Comments

The French press has long had a tradition of defending its freedoms and establishing high standards for reporting the news, political news in particular. Using it to promote democracy and educate the readers, it regularly engages in debates about what constitutes proper journalistic practice

There is a wide range of expression, from popular newspapers to intellectually challenging ones. In the 1970s the higher quality journals gained at the expense of the popular press owing to the increased urbanization and higher educational levels of the population. Le Monde , La Croix , and Le Figaro all grew while popular newspapers such as France-Soir , L'Aurore and Le Parisien Libéré lost readers.

Historical Traditions

The first French newspaper was born in 1631 as Théophraste Renaudot's La Gazette . The press grew slowly until the French Revolution which saw the birth of the opinion press along with information newspapers such as Le Moniteur Universel and the Journal des Débats. French public opinion was born, and, with the coming of the Industrial Revolution, the press gained a unique status of sole purveyor of information to the people. With freedom of expression guaranteed by Article 11 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen, the press became synonymous with the pursuit of democracy, and journalists enjoyed unprecedented freedoms in the absence of police interference and professional standards to restrain the editors.

Beginning in 1815, numerous changes took place. The introduction of the telegraph in 1845 and of the telephone in 1876, together with an increase in the nation's literacy, created a fertile environment and a growing demand for news. Charles Havas created the first news agency in 1832. The development of the rotary press and the use of wood-pulp paper, the new railroad networks, and diminished production costs, made mass production possible, and enhanced distribution. The nineteenth century was the golden age of press democratization. The first low-priced newspaper targeting a general audience was Emile de Girardin's La Presse , created in 1836. In 1863, Le Petit Journal refined this formula by inventing the popular press, characterized by simple writing with an informal, familiar tone. It found immediate success. Within five years it had reached a circulation of 300,000, thus becoming a European model.

During the nineteenth century, governmental policies alternated between liberalism and authoritarianism. The press continued to play a major political role, contributing to the revolutions of 1830 and 1848, weakening Napoleon III's rule after 1860 and influencing electoral outcome during the first years of the Third Republic. The Law of 29 July, 1881 ushered in a golden age of the press, which lasted until 1914. It firmly established the principle of a free press by suppressing paperwork (authorization to publish, down payment, "timbre," or a special tax) and limiting the definition of press law violations. Subsequently the number of newspapers increased. In 1914, Paris published 80 titles, and the regional and local press flourished, toppling 100,000 in circulation in large cities. Four titles monopolized the daily newspaper market: Le Petit Journal , with a circulation of 1 million in 1890, Le Petit Parisien , founded in 1876, which had a 1.5 million circulation in 1914, Le Matin , and Le Journal , hovering around 1 million circulation in 1914. These newspapers favored information over opinion, thus giving the appearance of neutrality; they also tapped the rich vein of popular literature, publishing it in installments. News reporting, a new technique, was an added ingredient of the newspapers' success. Overall, newspapers still relied very little on publicity. In 1914 France was the first consumer of news with 244 readers per 1,000 population, the highest readership it would reach during the twentieth century.

During the war, the French press became more uniform. The war years were marked by rising production costs, inflation, the cost of now commonplace photographic reproductions, increases in the price of paper, and rising social costs. After 1933, the slump in sales made newspapers rely increasingly on publicity revenues. The press became more concentrated as larger amounts of capital were needed to operate newspapers that became real enterprises. Le Petit Parisien created its own society, while the remaining four major newspapers associated around Havas and Hachette monopolized the daily newspaper market. Crises rocked and divided the press, from the Dreyfus Affair in 1894-1897, to anti-Semitism before World War I, and financial scandals in the 1930s. Some newspapers implicated in anti-patriotic acts during the war lost much of their credibility, especially Le Petit Journal . The dependence of the press on businessmen and politicians' self-serving purposes further discredited the press.

Between the two World Wars the highly politicized weekly press was born, such as the rightist Candide and the leftist Le Canard Enchaîné , the regional daily press developed, especially in the southwest regions, and the magazine press appeared with general information titles such as Jean Prouvost's Match and leisure and culture magazines. The first radio program was broadcast in 1921 and several local radio stations were created thereafter, with the state exercising tight control over them after 1933. The importance of news reporting on the radio increased after the riots of February 6, 1934. During the Front Populaire, the radio began to become a political forum for parties and politicians.

On the eve of World War II, censorship began to be actively enforced and in 1940 the government increased its control of the press by creating the first Ministry of Information. On June 14, 1940 all newspapers were shut down by the Nazis. As clandestine media developed, the press and radio were divided between collaborators and resistors. The French began to rely increasingly on the radio as their main source of uncensored information. At the Liberation of France in 1944, the temporary government issued three ordinances to protect the press from the intervention of political power, but also from financial pressures and commercial dependencies. The new press was highly politicized and ideological, and the surge of freedom seemed to bode well for its future, as seen in the creation of a host of new publications, including Le Monde in December 1944. However, press restructuring and increased publicity revenues could not prevent circulation from falling back to 1914 levels by 1952. In 1958 the Fifth Republic solidified the press's dependence toward the executive, while radio and television began to compete for the news market. In 1947, three national daily newspapers were party organs: the MRP's L'Aube , the Socialist Party's Le Populaire and the Communist Party's L'Humanité . By 1974 onlyremained.

After World War II, the press began to receive governmental subsidies. By 1972 these subsidies represented one-eighth of the total turnover of press enterprises. A decree of 1973 fixed the conditions under which the subsidies could be granted to newspapers with a circulation under 200,000, limiting their revenues from publicity to 30 percent. The sixties and seventies were marked by an increase in regional press concentration. Emilien Amaury regionalized the daily Le Parisien Libéré , while Robert Hersant created one of the first French press groups that began with his Auto-Journal in 1950, continued through a series of regional newspaper acquisitions, and culminated with the control of Le Figaro in 1975, which prompted the resignation of editor Jean d'Ormesson and best-known columnist, Raymond Aron.

Regionalization also characterized television, with a regional station opening in 1973 in addition to the other two state-controlled television stations. Weekly magazines such as L'Observateur and L'Express , and Paris-Match, founded in 1949 by Robert Prouvost, were founded with great success. Two national daily newspapers emerged in leading position at this time, Le Monde and Le Figaro . The regional press began to modernize in the early 1970s with offset, digital, and facsimile techniques. Those costly moves caused a concentration and regrouping of the titles whose number dropped from 153 to 58 between 1945 and 1994, erasing ideological and cultural differences. A few large groups dominated. Hersant controlled 30 percent of the market with Le Dauphiné Libéré , Paris-NormandieLe Progrés de LyonLes Derniéres Nouvelles d'Alsace, Nord-MatinNord-Éclair , Le Havre-Libre , and Midi-Libre among others. Hachette-Filipacchi Presse controls the south with Le Provençal , Le Méridional , La République , while smaller groups are centered around a newspaper. Some such examples are Ouest-France , Sud-OuestLa Dépĉche du Midi , and LaVoix du Nord. Ouest-France is a leader with a circulation of over 800,000, 17 editions, and sells in Brittany, Normandy, and the Loire departments.

In the 1980s the press had reached a fragile equilibrium between pluralism and market constraints. Concentration continued while the Socialist government strengthened the pluralism of the press, deemed essential to the democratic debate in its law of 23 October 1984. A new set of laws of 1 August and 27 November 1986 prevented monopolies by establishing a 30 percent circulation limit to national and regional daily newspapers controlled by a single press group. As a result, groups such as Hersant began to invest abroad, notably in the former Eastern European countries, after the end of the Cold War in 1989. Economic realities also brought about restructuring of the printing and distribution networks. Between 1985 and 1990, however, profits were assured only by the growth of publicity revenues, while the national daily press experienced major difficulties.

The recession of 1989-93 brought more changes. The information revolution also prompted a radical reevaluation of the way news was written and distributed. Once rare and expensive, the news became overabundant, which dealt a severe blow to the French press, although it is a development common in other countries. Competition came not only from the Internet, but from radio and TV, which multiplied their news delivery, and also from an unexpected source, books that started dealing with current events, a field heretofore monopolized by newspapers. Due to France's experience with Minitel in the 1980s, a digital distribution system controlled by the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunication, France hesitated to embark upon yet another modernization. But the public was beginning to ask for free news. Some newspapers responded with an upscale presentation and simplified analyses, while others, like Le Monde , opted to serve the more educated, more sophisticated public of the modern, "complex" societies that required a new kind of information. The restructuring of the 1990s benefited the three main newspapers, Le Monde , Libération , and LeParisien-Aujourd'hui, whose circulation stabilized in 2000. Press groups restructured as well. Hachette, which diversified into publishing, distributing, and radio broadcasting, Amaury, which diversified into the sports press and women's magazines, Prouvost which diversified around women's magazines and the very successful Télé 7 jours , and Del Duca, specialized in La Presse du Coeur , a popular press, and Télé Magazine .

Economic Framework

Print Media versus Electronic Media

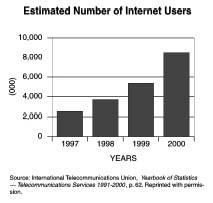

In the 1980s, France was the first country to put a newspaper online by using a revolutionary system called Minitel. The publicity-free, pay-per-usage time service's profitability, added to the large investments made in Minitel explain why France was slower than other European countries to adopt the Internet in the 1990s. In 1996, France had seven online daily newspapers out of the total 84 and 19 online magazines out of all 294 online. In October 1997 Les Echos became the first newspaper to offer an online version with part free news and part pay-per-article. With the new millennium, however, things began to change quickly. The increase in internet use can be measured by the

The best known and largest newspapers were not the first ones to go online. Their reluctance opened the door for smaller, more technologically oriented newspapers to make a name for themselves. Regional and small newspapers that embraced the new technology quickly made a name for themselves. For newspapers specialized in economic and financial news, such as Les Echos , the Internet was a natural medium. In 2002, a substantial proportion of newspapers had developed internet sites, especially regional newspapers.

Many titles have more than one site, showing that general and political news have lost the prominent place they once occupied. The Groupe Nouvel Observateur , in addition to its initial magazine site, has 14 specialized sites, including car, health, stock market, women, culture, real estate, economic and financial. Les Echos has seven sites, including employment, sports, and news. Online editions require substantial makeovers since site attractiveness is a must, especially in the advertisers' opinion. At first the internet press was totally dependent on publicity revenues, which it had no difficulty attracting. The new partnerships between technology and editorial policies, however, gave newspapers new revenues by developing commercial services such as e-commerce, e-bank, e-tickets, e-travel, and pay per view services. Archival services and royalties represented additional sources of revenue, and so will the use of "cookies" which was being considered in 2002. The new sites are interactive, allowing the online press to receive feedback and to monitor its audience (the first statistics were created in 1998). Employment, real estate sites, classifieds and personalized pages are among the other services offered.

Types of Partnerships/Ownership

The traditional economic structure of newspapers, with limited capital and a delicate balancing act between publicity revenues, state subsidies, and sales revenues, has all but disappeared. The new technology requires the support of financial-technological support groups, thus turning the press into veritable enterprises. The new press magnates are the technological magnates, the announcers and the sponsors.

In the 1990s, the news media became a fast expanding economic sector attracting not only domestic, but European industrial and banking giants. Libération , a mouthpiece of the left founded in 1973 under the aegis of Jean-Paul Sartre, was taken over in early 1996 by the industrial group Chargeurs. In October 1995, the Havas publicity group together with Alcatel bought several important newspapers including L'Express , Le Point , and Courrier International . One of the few newspapers which remains internally controlled by its stockholders is Le Monde .

The editorial independence of the media appeared threatened, which caused a significant drop in circulation sales between 1995 and 1996, indicating the public's lack of confidence in the media, especially when the Tapie, Botton, and Dumas scandals revealed the extent to which investigative journalism had been choked. The press, which historically was built in opposition to political power, now seemed closely associated to it, even to the point of losing self-criticism. This new version of the power triangle between the media, big business, and politics, was somewhat addressed by an understanding between editorial offices and publicity leading to their "sacred union," and by repeated governmental measures stressing the role of the press as guarantor of democracy and pluralism.

Concentration of Ownership

The late 1990s saw the formation of large press groups controlling both technology and editorial content, with the major French investor being the Vivendi group. The main press groups are: Bayard Presse, Excelsior Publications, Groupe Moniteur, Groupe Quotidien Santé, Havas, Milan Presse and Prisma Presse.

Bayard France, the first Catholic press group, regroups the press, book publishing, and multimedia. Created in 1813 with the magazine Le Pélerin , it added La Croix in 1883, which was still in print in 2002. It publishes more than 100 magazines in the world, of which 39 are produced in France and 50 abroad. It is the leader of the educational youth press, religious press, and mature adults press. It is the fifth French group by diffusion, with 7.6 million buyers and 30 million readers worldwide. It features seven internet sites.

Prisma Presse features five weeklies, nine monthlies, and one biannual publication. Prisma TV deals with televised news. The group distributes 277 million copies a year and owns 18 percent of the French market. Created in 1978 within the group Gruner and Jahr, it publishes popular magazines such as Femme , CapitalCuisine Actuelle, and the National Geographic which it co-owns since 1999 with RBA Editions.

Distribution and Printing

The main press distributor remains the Nouvelles Messageries de la Presse Parisienne. In 2001 they owned more than 80 percent of the sales market with two other distributors the MLP and Transports Presse. Created in 1947 from a partnership between the Hachette bookstore and Parisian press publishers, they guarantee and promote the diffusion of the written press in France and abroad. In 1986 the NMPP began an intensive campaign of modernization that was sped by the 1989 economic crisis. After 1991 they assisted publishers in order to maximize circulation; they also created new sales locations, especially in the Paris region, and automated distributors. More modernization and geographic rationalization followed in the 1990s. In the 1990s NMPP continued to centralize and relocate in order to reduce cost and to improve service. They reduced personnel by one-third, and introduced online links with editors and press merchants.

In 2001 they represented 697 publishers and distributed 3,500 titles (dailies, magazines, and multimedia products), including 26 national daily newspapers, and over 900 foreign newspapers and magazines, for a transactions figure of 5,176 billion Euros distributed (of which 2,791 billion Euros sold), 2,658 million copies, 560,000 tons of titles. Unsold copies, averaging 46 percent, are recycled. The NMPP exported to 113 foreign destinations, 2,727 titles for an amount of sales of 286 million Euros, or 10 percent of its total sales. It employed 2,089 people. The NMPP is owned for 51 percent by five press coops and for 49 percent by Matra-Hachette which operates the firm. NMPP tariffs favor the daily press.

These issues plague NMPP: the decreasing number of newsstands in Paris and a low portion of the magazine and weekly press market. Despite restructuring, NMPP was still having financial difficulties in 2000 and for state subsidies of 250 million francs. The state was also called in to mediate a dispute in 2000 when NMPP tried to give favorable tariffs to periodicals.

Messageries Lyonnaises de Presse (MLP) regroups 200 clients and distributes 650 titles in France. In the 1990s, MLP grew considerably, cornering the magazine and weekly publications' market. In 1998 their turnover was 2.7 billion francs. Previously, in 1996, the MLP held 9 percent of the paper distributed in France which provided lesser operating costs and expanded into the Paris market.

There are 31,504 press merchants, of which includes 1,210 "Maisons de la Presse" stores (a combination newsstand, bookstore, and stationery store), 753 kiosks, of which 315 are in Paris, and 2,784 sites in shopping malls. The press kiosks in Paris diminished in numbers from 370 to 310 between 1999 and 2002. In 1988 there was one sales location for 2,100 Parisians, a ratio twice that in other parts of France. Editors asked the Paris mayoral office to help, since newsstands sales represent more than one-third of all sales of daily newspapers in Paris, and a press subsidies of 750,000 Euros was granted. In an effort to stem this decline, newsstands operators were given greater input about the number of copies they were assigned and press merchants signed an agreement with the Union Nationale des Diffuseurs de Presse (UNDP) in 2001 granting them a 15 percent fee. Today the situation appears to have stabilized.

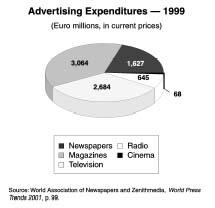

Advertisers' Influence on Editorial Policies & Ad Ratio

In 2000, publicity revenues for the press were 28 billion francs, a 10.2 percent increase over the 1999 revenues, roughly half the publicity revenue of all media combined. The press thus remains the main media support for publicity investments. In 2000, it attracted almost 42 percent of the media market, far ahead of television (30 percent) and radio (7 percent). The publicity revenues come from commercial publicity for 80 percent and from classified for 20 percent. The main buyers of publicity were the magazine press (40 percent), followed by the daily regional press (24 percent), the specialized technical and professional press (18 percent), the daily national press (16 percent), and in last place the weekly regional press (2 percent). 40 percent of the purchases of internet publicity space were destined to editorial sites (written press, TV and radio).

Despite the predominance of print advertising, however, over the past 20 years, the printed press lost 13 percent of the publicity market, much of it to television. In 1980 the press received 60 percent of all publicity revenue and television 20 percent, but in 2000 it received only 47.3 percent of it (including classified), whereas television received 33.5 percent. The prolonged economic crisis and the competition from television, plus the fact that alcohol and tobacco ads were curtailed, contributed to this decrease. In 2000, the turnover's ratio between sales and publicity revenues was approximately 60 and 40 percent, respectively.

By contrast, publicity on the web has increased dramatically. To finance the Internet press, several commercial methods were used: publicity, classifieds, auction sites, e-commerce, and cookies. 95 percent of e-sites were financed in 1999 by publicity, with the pay-perview option remaining small. At first, e-publicity revenues remained small at 113 million francs in 1997, compared to 400 million francs of publicity revenue for Le Monde in 1998. Les Echos 's e-publicity revenues of 1.2 million francs in 1997 more than doubled in 1998, reaching in excess of 3 million francs, and outpaced pay per view revenues, while its printed version saw a total publicity revenue of 300 million francs. However, in 1998, the price of online publicity surpassed the printed press's publicity price, prompting many newspapers to offer an online version in order to protect their revenues, especially with regard to publicity. The price of publicity is governed by a December 1, 1986 decree which established flat publicity rates that were eliminated for newspapers with a large circulation by a Circulaire of October 28, 1993.

While many announcers buy space online directly, newspapers increasingly buy publicity from a middleman or specialized purchasing group. France plays a leadership role and serves as "interactive task force." Announcers who want to advertise internationally prefer to deal with French groups, whose leader is Carat with 20 percent of the investment for printed media in 1998. Carat France was the first online firm to adopt the multimedia. In 1994 it created Carat Multimédia under the sponsorship of Aegis. Besides Carat Multimédia, Ogilvy Interactive and The Network, which claims to be the first buyer on the internet market in France, Médiapolis, Optimum Media and CIA Medianetwork are the main buyers of internet space. European and international giants have an edge, however, some examples being RealMedia, Doubleclick, Interdeco (of the group Hachette Filipacchi), Accesite (dedicated to Francophone markets), or InterAd (specialized in European markets). Many purchasing groups are tied to a main client, such as France Télécom, which brought Médiapolis between 3 and 4 million francs in 1998.

France is also involved in the U.S.-based, publisher-controlled Internet Advertising Bureau, which was founded in 1996 and serves the main U.S. and foreign newspapers. France led in the creation of IAB Europe which is based in Paris, and of IAB France which in 1998 served Libération , Les Echos , and all 40 publications of the groups Hachette Filipacchi and Hersant. Several regional newspapers are also represented in IAB through their online publicity companies Realmedia and Accesite.

Another issue unfolding is whether to couple paper and web advertising. The Internet press has been banned from advertising on television since March, 1992, but the debate is ongoing, especially since CSA's decision in February 2000 to allow Internet sites, including the press sites, to advertise on television. Although the Conseil d'Etat in July 2000 reversed this decision, the debate continued, with the Syndicat de la Presse Magazine et d'Information (SPMI) favoring access to televised publicity in view of the competition from the new media.

The world of advertisers is complex and totally internationalized. One of the main advertising representatives is S'regie, an international media sales group. Headquartered in Paris and Brussels, it represents the press, TV, online, outdoor, and radio. In 2002 the publicity group Publicis bought the US Bcom3 and entered in a world exclusive agreement with the Japanese group Dentsu. The first action made Publicis the fourth publicity group worldwide, while the second action gave its clients a privileged access to the Asian market.

Special Interests and Lobbies

With lobbies not much a part of the French tradition, there are few press lobbies, and they are all recent. A users' association, IRIS (Imaginons un Réseau Internet Solidaire), was created in 1997. Older, established consumer organizations such as the French Consumer Association or the National Union of Family Associations have opened departments dealing with Internet issues. In June 2001 a new group was created called Enfance et Média (CIEM) to prevent violence on television. It would produce a report in March 2002 to the Minister of Family, Childhood, and Handicapped Persons.

In France, one may consider professional associations and trade unions as lobbyists. Some of them represent their profession in governmental agencies and para-governmental and inter-professional organizations, such as FNPF.

Journalist: An Expanding Profession

The statute of journalists is defined by the collective labor contract for journalists, which was passed as Loi Guernut-Brachard in 1935. The statute was revised in 1956 under the leadership of Marcel Roëls, and then in 1968, 1974, and 1987. Since 1944 French laws have guaranteed the independence of journalists. The Articles L 761-1 to 16 of the Labor Code which were passed in January, 1973 define four kinds of journalists: (1) professional journalists who "have for their main, regular, and salaried occupation and income, the exercise of their profession in one or more daily or periodical publication or in one or more press agencies." This includes correspondents who work in France or abroad in the same conditions are professional journalists; (2) "assimilated" journalists who work in related occupations or direct editorial collaborators such as redactors-translators, stenographer-translators, redactors-copy editors, reporters-graphic artists, and reporters-photographers; (3) pigistes ; and (4) temporary journalists or substitutes. A salary grid reveals a maze of job titles that indicates a great deal of nuances and complexities as well, listing as many as three "categories" differentiating the level of pay and responsibility. Pigistes occupy a position unique in the world of journalism, in between free lancers and tenured journalists. They are considered professional journalists since the 1974 Loi Cressard. Finally there are collaborators, namely well-known academics or specialists collaborating occasionally with an opinion piece, for which they are paid in royalties. Publicity agents and occasional collaborators are not considered journalists.

The number of card-holding journalists more than quintupled between 1950 and 2000. On the other hand, the number of new journalists showed a decline in the 1990s, with a significant drop to 1700 in 1993, during the crisis of the press. Overall, the number of journalists increased in the 1990s, from 26,614 in 1990 to 30,150 in 1998. In 1990, 9.3 percent of those were new journalists, while in 1998 this figure dropped to 6.9 percent. The profession has become less secure and increasingly competitive, with journalists leaving the profession at a high rate after a few years when their career does not take off as hoped, and employers prolonging the "trial" period. Also, journalism has become increasingly a second profession and students have been getting higher professional education degrees in order to be more competitive. In 1998, 90.6 percent of all journalists were considered to be employed in basic positions, with less than 10 percent in leadership positions. The number of pigistes among the new journalists increased between 1990 and 1998 in several media: the "suppliers" (photo and press and multimedia agencies), the regional television stations, and the general and specialized press. In all, one in five journalist works as a pigiste . There is a large proportion of pigistes among reporter photographers.

Overall, the average journalist today is older. Only 25 percent of journalists in 1998 were 25 and younger. The median age of journalists is 31 for men and 30 for women, with 21 percent of the new journalists being over 36 and 13.2 percent over 40, and into their second career. Men are slightly more numerous, with 51.9 percent, against 48.1 percent of women, yet they hold managerial and leadership positions in significantly larger numbers than women.

For journalists, the job market is diversified, highly competitive, and there is no sure career path owing to the changing nature of the profession. The three major sources of jobs are the specialized press for the public, the specialized technical and professional press, the daily regional press, which totaled 55.6 percent of the job market in 1998. Interestingly, the national daily press represented only 5.3 percent of the job market, in decline from 6.1 percent in 1990. Local radio stations, press agencies, and regional television stations were the next big employers, with 6 percent, 3.8 percent, and 3.6 percent respectively.

Two-thirds of all new card-holding journalists are employed in the Ile-de-France region, a number that remained steady in the 1990s, although it dropped a few percentage points to 63.7 percent in 1998. Besides Paris, three main regions attracted roughly five percent of new journalists each in 1998: Rhône-Provence, Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur, and Bretagne. The press offers 72.6 percent of the jobs, while radios and television stations hover around 10 percent of the market. Female journalists are more numerous in the specialized, public and specialized press, while men dominate the regional daily press, local and national radios, and local and national television stations. Women are more frequently administrative assistants, while men occupy two-thirds of the reporter-photographer jobs and almost all the jobs as photojournalists.

Employment and Wage Scales

The average monthly salary of a journalist was FF 10,740 in 1998, with almost half of the journalists earning between FF 7,000 and 10,000. Salaries have not kept up with Cost of Living Allowances (COLA), thus lowering of the economic position of journalists. The majority of pigistes are paid below FF 7,000 a month. The lowest salaries are paid by local media, radio stations, and the suppliers (agencies). The generalist media has a large percent of regular low paid journalists and only 25 percent of its regular journalists earning salaries superior to FF 15,000.

At the level of a national daily, the pay scale varies from 1,562 Euros for an intern to 4,728 Euros for an editor-in-chief. A reporter could expect 2,612 Euros, and a photojournalist the same.

All journalists benefit from the protections granted by the Convention Collective, or Labor Contract, which includes social benefits such as paid vacation, thirteenth paid month, firing notice, indemnity of firing, unemployment benefits, medical, insurance and invalidity benefits, and pensions; as well as legal recourse in case of conflict with an employer. They also benefit from the 10 percent to 20 percent tax relief granted all taxpayers, as well as from tax deductions for professional expenses which could total up to 7,650 Euros in 2002. The state also reimburses 50 percent of the trade union membership fee.

Article L761 stipulates the conditions in which journalists receive severance pay, established an arbitration commission, and state that all work requested or accepted by a newspaper or periodical enterprise should be paid whether it is published or not. It contains provisions protecting the reproduction of articles and journalistic work. An employer-employee board established by this decree is in charge of establishing a list of newspaper or periodical enterprises who hire professional journalists, of establishing salary grids, and arbitrating disputes.

Major Labor Unions

The first journalists' unions appeared in 1918 with the "Journalist's Charter." Today there is a host of professional labor unions, which adapt to the many changes experienced by the profession. Among noted developments, journalists in 1991 joined the SCAM or Société Civile des Artistes Multimédia, thus joining forces with illustrators, audiovisual, radio and literature authors. Also, the European Federation of Journalists was created in France in 1952 as a branch of the International Journalists' Federation and represents more than 420,000 journalists (salaried and free-lance journalists) in more than 200 countries. It has consul-tant's status within the United Nations, UNESCO and WAN.

Industrial Relations: Copyright Laws and the Status of Journalists

Copyright issues are complex issues that are the object of intense lobbying from journalists' associations. At issue since the 1885 Bern Convention that gave journalists ownership of their work is whether a newspaper is an collection of individual articles, or a collective work. In contrast with other European countries, France recognizes the moral right of journalists to own their work. The information revolution, by increasing both the reproduction of works and the danger of plagiarism, reopened a debate that is far from being concluded. A new issue is whether journalists or computer specialists retain editorial control of newspaper's Internet version. When Le Monde almost published an obituary of Communist Party Secretary George Marchais six months before his death, the world of journalism was alarmed.

Several newspapers have signed agreements with journalists' unions in anticipation of electronic developments, such as Les Derniéres Nouvelles d'Alsace in 1995, after negotiations with the National Conciliation Commission of the Presse Quotidienne Régionale and a lawsuit, and Le Monde in 1997, for a two-year period. The DNA compromise gave collective property of the articles to the newspaper and paid journalists for internet and television use of their materials. Journalists retained their moral and financial rights, yet the newspaper could bear a heavy financial burden. Le Monde agreement recognized journalists as authors who were compensated for ceding their copyright. Les Echos favored a model in which the printed and electronic versions were treated as one, with journalists retaining rights for the reproduction of their articles under another form, such as a thematic dossier, or their reproduction by an external group that might censor or cut their prose and getting 5 percent and 25 percent of the proceeds, respectively. Journalists and publishers remained sharply opposed; the Havas-Vivendi directors, for example wanted journalists to renounce their copyrights. In June 1998 the Conseil d'Etat suggested to treat journalists' copyright as patents, but the problem of the extent of the newspaper's vs. the journalists' rights remains to be resolved.

In 1998, journalists organized a debate on the subject. The development of the free press in Italy and France not only created new competition but operated outside of the legal provisions of the National Labor Contract, thus prompting Italian and French journalists to create a joint coordination committee with the participation of both countries' main syndicates. USJ-CFDT also asked for a general debate about the treatment of information.

Syndicates also examined the statute of reporter-photographer whose situation is doubly precarious, owing to their status of photographers and pigistes . In January, 2002, with the prospect of new provisions about copyright by the Conseil Supérieur de la Propriété Littéraire et Artistique (CSPLA), the USJ-CFDT and SNJCGT joined forces with SCAM despite ideological differences in order to organize the defense of copyright. Editors and journalists are at odds on the subject, with lawsuits such as that of the audiovisual group Plurimedia. It appears that the CSPLA is lobbied by publishers to erode copyright. Since the tribunals have generally upheld journalists' rights, the publishers concentrate on changing the law while authors organize to devise collective contracts among multimedia, such as the "Excelsior" contract.

Cost, independence, and quality are three major issues, as is the statute of journalists. The creation of a new breed of "cyberjournalists" not covered by the legal statutes of the profession, the concentration of information, the marketing and budget pressures tending to reduce the quality of journalism, and threats to the freedom of information in the form of exclusive coverage or the control of visual information, have already raised the job insecurities. After the adoption of the 35-hour workweek, journalists pushed for a reduction to 32 hours. Citing a rising unemployment, the loss of job security, and the increasingly demanding nature of the workload, the USJ-CFDT, following the CFDT, asked for the creation of new jobs parallel to the reduction in the number of work hours.

Circulation Patterns

The average price of a daily newspaper is higher than in Great Britain or Germany despite state subsidies: Le Monde sells for $1.25 FF while The Times sells for $0.30 FF. Once set at the same value as a domestic letter stamp, the price of a newspaper increased eightfold between 1970 and 1980 while the cost of living increased only four-fold. This is in part due to high distribution costs that represent 40 percent of the average sales price of the newspaper, the second highest distribution cost in Europe. Without state postal discounts and tax breaks, the price of newspapers would be even higher. Several provisions govern price and competition, especially the December 1, 1986 decrees. There is a 2.1 percent VAT on all printed media that does not apply to the internet version of newspapers and publications. In fact, European community law does not recognize electronic support as "written press" and electronic newspapers are thus considered data transmission, yet another non-negligible advantage.

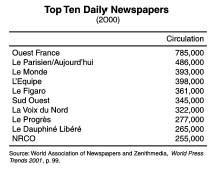

In 1996, France exported 2,000 titles to 107 foreign countries, bringing in a turnover of $45 million FF. Approximately two thirds of sales occurred by subscription, with only one third in newsstands or libraries. The top five daily newspapers by circulation in 2000, according to World Press Trends 2001 , were Ouest France with 785,000, Le Parisien combined with Aujourd'hui at 486,000, Le Monde selling 393,000, L'Equipe providing 398,000, and Le Figaro releasing 361,000.

Press Laws

Constitutional Provisions and Guarantees Relating to the Media: Freedom of the Press

Freedom of the press is one of the basic freedoms in France. It was written in the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen which established freedom of expression "except in abusing this freedom in cases set forth by the law." France, which was thus one of the first countries in the world to guarantee freedom of expression, has made several exceptions to this guarantee, both in judicial decisions and legal decisions found in the Penal Code, the Code of Penal Procedure, the Code of Military Justice, the Law of 29 July, 1881, and circulars, notes, and decisions by France's supreme judicial authorities.

Summary of Press Laws in Force

Press laws in force deal with the countless aspects of the media industry. There are laws for each aspect of the profession: publishers, journalists, distributors, and vendors. There are laws of the press and laws for the audiovisual industries, and now cyber laws. The main laws relating to the written press itself deal with the freedom of the press and editorial freedom, criminal offenses, collective labor contracts, copyright laws, and registration of newspapers and journalists. In addition to the laws there are scores of legislative acts providing for state regulation of the media. Those are subject to constant reorganization. In addition to national laws, France is subject to European Union laws and court decisions that have come into effect in the 1990s. The Law on the Information Society, for example, which was introduced in Parliament in June 2001, would be unthinkable outside of European Community law, especially in the areas of e-commerce, electronic signatures, and cyber criminality.

Registration and Licensing of Newspapers and Journalists

Periodical publications with public circulation are subjected to strict laws. A newspaper must register with the Attorney General its intention to publish and its title, frequency of publication, name and address of the director of publication. To protect the publication's title, it must be registered with the INPI, or Institut National de la Propriété Intellectuelle. If the publication is destined for the youth, an additional declaration must be registered with the appropriate oversight committee at the Ministry of Justice. The basic Law of 29 July 1881 has been modified by the laws of 21 June 1943 and 31 December 1945, the law of 10 August 1981, a decree of 3 December 1981, a law of 27 August 1998 and a directive of 22 December 1998.

Journalists must obtain the Carte d'Identité des Journalistes Professionnels (CIJP), which is granted by a commission that was created by the Law of 29 March 1935. In 2000, the Commission delivered 32,738 such cards. Article L761-2 of the law indicates that the professional journalist is a person who "has as his/her main, regular, and salaried occupation the exercise of his profession in one or more daily or periodical publications or in one or more press agencies, and who derives his/her main income from this work." Excluded from this definition are the publicity agents, although occasionally journalists may be paid for publicity work. An edict issued by the Minister of Information in October 1964 declares public relations officers and press attaches to be non-journalists. In May 1986, a statute by the State Council also excluded public servants from this definition.

In order to qualify one must have exercised or plan to exercise the profession of journalist for three consecutive months and derive more than 50 percent of one's income from it. Candidates to the CIJP must also specify which activity and which type of company they will work. The Law of 1935 created the Commission in Paris; in 1948 provisions were made to add regional correspondents.

Sunshine Laws, Shield Laws, Libel Laws, Laws against Blasphemy and Obscenity, Official Secrets Acts

The basic text defining press crimes is the Press Law of 29 July 1881. Limitations on freedom of speech include defamation, insults, offense and outrage, which are fairly broadly constructed. The Law of 1881 provided the possibility of criminal and civil action against journalists. Until the Law of June 15, 2000 the presumption of innocence and the victims' rights was reversed and the burden of proof was shifted from the accuser to the accused. The 1-year prison sentence for libel has now been abolished.

Specific cases of label are strictly regulated. The Law of 1881 punishes offenses toward public authorities, official bodies, and protected persons. This includes foreign heads of state as well as government officials and government bodies. The punishments were lessened by the law of June 15, 2000, and the right to free expression protects journalists in most cases. However, for publishing the picture of a handcuffed person without the person's approval, journalists can be fined 100,000 francs. Two laws of July 1972 and June 1990 forbid libel against persons and groups "based on their origin, ethnic identity, race, or religion." The 1990 law forbids revisionism, i.e. denial of the Holocaust. In those two instances libel constitutes a press misdemeanor.

Litigation is secret as of Article 11 of the Criminal Procedure Code of 1957 which limits journalists' freedom of access to information. Revised by several circulars, most notably in 1985 and 1995, and by the Law of June 15, 2000, the law provides for exceptions, however. Public prosecutors may publish information, appeals and search notices necessary for the progress of legal proceedings, helping the accused's cause, or putting an end to the spreading of rumors and false truths. They may also correct erroneous and incomplete information about victims or make public certain elements of litigation in order to prevent false information from being published. Recently, journalists convicted before the French law have begun to take their case before the European Court of Human Rights to which France is subjected as a signa-tory of the European Convention of Human Rights. The ECHR does not support the secrecy of litigation. Overall, violations of Article 11 are fairly common, with journalists acting as the gadfly of a judicial system plagued by lengthy procedural delays, and with the European Community providing new guidelines. Few violations are ever punished.

The right of journalists to protect their sources has been recognized by French law since 1993, unless they abuse that right. Article 109 of the Criminal Code protects investigative reporters' journalistic sources. With recent terrorist threats, the issue of revealing information sources came anew. The Ministry of Justice in March, 2002 did not change those provisions in the wake of the new Law on Domestic Security that dealt with the war on terrorism. The official position is however that the criminal responsibility of journalists could be involved if not divulging their information sources endangered that source's life or security.

Finally a June 1998 law punishes pornography on telecommunication supports. This law is meant to protect children who are under age and is particularly severe for perpetrators of child pornography who establish contacts with their victims via a telecommunication means (Minitel or the Internet).

Cyber Communication and Copyright

Online communication is protected by the September, 30 1986 law about freedom of communication. Electronic documents must be legally registered as of a law of June 1992, and illegal sites are subject to sanctions. Much French legislation in this domain is already harmonized with European legislation. The French government in the 1990s was an active participant in promoting international policies, especially in terms of uniform pricing, protection of intellectual property and authors' rights. The European Council in 1994 initiated the European Directive which created an internal market to regulate competition, protected intellectual property rights, the right to freedom of expression, and the right of general interest, and encouraged investments in creative and innovative projects. France adopted the European Directive on July 2, 1998; it protects original database content and support. A new copyright law is expected following France's adoption of the European Parliament and Council's May 2001 Resolution on Copyright.

France in November 2001 signed the International Convention on cyber criminality, which punishes copyright infractions. Cyber crimes benefit as of November 2000 of a decision of the Cour de Cassation providing for immediate litigation rather than the three-months delay granted to the printed press. Internet providers are not responsible for crimes committed by internet services except if they fail to prevent access to that service if the justice system notified them of the crime.

Censorship

Agency Concerned with Monitoring the Press

Journalists and editors practice self-censorship by tradition, and because of the deterrent value of state subsidies and laws limiting the freedom of the press. Just as indirect government influence is a tradition, journalists walk a fine line when they write articles for Le Canard Enchaîné or skits for the television program Les Guignols de l'Info . In both instances they use the many registers of political caricature deftly so as to escape the accusation of libel, while providing needed distance toward reality as well as reaction against "dominant conformism." A good indicator of the nature of censorship is the fact that the government has not been, nor does it plan to get involved in two major aspects of journalism: training/education and the discussion of journalistic ethics. French journalists have long been self-policing in the area of professional ethics. The professional code of journalists defines their role and responsibilities in a democratic society.

Case Studies

Recent case studies show an uneven degree of tolerance for the press's behavior. In 2000, the Commission des Opérations de Bourse, which has investigative powers, conducted an investigation at the headquarters of Le Figaro while investigating a financial and economic scandal relating to the Carrefour-Promodes store. The journalists protested that this was a house search. In 2000 AFP was reprimanded by the government after selling prison pictures of Sid Ahmed Rezala to a newspaper. At issue was the fact that AFP had treated the picture as merchandise, not information. Publications by religious sects were not deemed subversive to the public order, and the government ruled in 2001 that transportation societies could not refuse to carry those publications to the press distributors.

The relationship between the press, power, and the judicial system in France is in a state of suspended animation. Political power can be heavy at times, such as in the presidential appointments of AFP directors. The 1975 appointment of Roger Bouzinac as AFP director provoked the resignation of Hubert Beuve-Méry who was AFP's chief administrator. Yet this practice continued in the 1980s and 1990s, signaling a political desire to control the main provider of information in France.

Relations between the press and the government became particularly tense under the second term of François Mitterrand, showing the degree of restraint of the press. After the suicide of prime minister Pierre Bérégovoy in 1993, the press asked itself whether journalists' revelations of apparently questionable financial dealings had not been responsible for his death. After President Mitterrand's death, the public learned that the press had known about his secret illness, cancer, long before disclosing it to the public, in a procedure reminiscent of the press's behavior during the last three years of President Pompidou's life, twenty years earlier. In 1997, the death of Princess Diana opened a debate about professional ethics, showing that some paparazzi's appetite for sensationalism may have contributed to the car accident that claimed her life and that of her companion Dodi Fayed.

The eruption of several political scandals in the 1990s (the Bernard Tapie, Alain Carignon, and Pierre Botton scandals) created a renewed demand for professional ethics. In May 1994, journalists formed an association to strengthen the professional ethics and denounce in particular the practice of the false "Une" (based on publicity rather than real news). Jean-Louis Prévost, CEO of the Voix du Nord , asked for a strengthening of investigative reporting and a better oversight of regional governmental accounting offices and tribunals. The public called for truth in information and voted with their purse: Ouest-France , Le Télégramme de Brest , and Le Parisien which improved their opinion and editorial policies, saw their circulation increase.

Composition of Press/Media Councils

There are numerous governmental boards regulating the media in addition to the professional paritaire (employer-employee) boards which are under governmental oversight. There is no strong parliamentary oversight of the media. Governmental boards exist mostly to plan, give direction, and assist. This indicates a degree of cooperation between the public and private sectors that is a long tradition in France known as étatisme or dirigisme . The most important board is perhaps the Commission Paritaire des Publications et Agences de Presse whose statute was revised according to a decree of November 20, 1997 and whose function is to grant a registration number to publications and granting fiscal and postal tax exemptions. Next to it is the Commission de la Carte d'Identité des Journalistes Professionels (CCIJP) which grants the press card and the coveted journalist's status. Other boards such as the Conseil Supérieur de l'Audiovisuel or the Centre Français d'Exploitation du Droit de Copie deal with specific issues. The transportation and distribution enterprises are controlled and regulated by the Conseil Supérieur des Messageries de la Presse. Affiliated with the IFJ, the Union Syndicale des Journalistes CFDT has representatives in the main governmental and professional commissions dealing with journalism, journalistic training, ethical questions, granting of the press card, editorialists' rights, collective bargaining and arbitration commissions.

State Leadership in Promoting the Information Society

The French government has taken an active role in promoting the information society and changing the educational, administrative, and communication cultures simultaneously within its own institutions and without. A flurry of decrees has been passed in the last few years, especially since the European Directive of July 2, 1998, that established the framework for the Information Society. The French government has actively defined and regulated the new technologies' uses, literary and artistic property (copyright), legal protection of databases, and e-commerce. While France provided active input on pricing, intellectual property and authors' rights, its legislation is inseparable from European Union legislation on those matters. Both the European Union and France are currently developing a plan for the new Information Society. Anticipating the European Directive in January 1998 an Interministerial Committee for the Information Society (CISI) was created to devise a governmental program to support and give direction to the development of the Information Society.

The Prime Minister's office is most important in shaping the Information Society. Several organizations dependent on his office coordinate this initiative which develops in consultation with European legislation. In November 2000 the Direction du Développement des Medias replaced an earlier committee charged with defining governmental politics toward the media and the services of the information society in order to assist the Prime Minister with drafting his decrees. The Foreign Affairs Ministry plays an important role as well as the Ministry of Education. While the former sees the development of new technologies of information and communications, or NTIC, as an opportunity to develop French presence abroad and to promote the use of French language, the latter's CLEMI or Centre de Liaison Enseignement et Moyens d'Information educates the public about the media, mostly internet. Once again, the media are seen as inseparable from education and democracy.

State-Press Relations

Relations of the Press to Political Power

While there is no Information Ministry in France, the relationship between political power and the media is complicated and symbiotic. In postwar France, the intervention of the state in the life of the media was qualified of "chronic illness." For one thing, there is an active revolving door policy. French politicians in the past often used the press as a political trampoline. The practice continued under the Fifth Republic. The National Assembly in 1997 counted some twenty deputies who had been journalists, nine of whom belonged to the Hersant Group which was built with the tacit approval of the authorities. This phenomenon was repeated in towns such as Saint-Etienne, Lyon, Vienne, and Dijon which had elected journalists in their midst. In 1997, the Director of France 3, the national television station, was former prefect Xavier Gouyou-Beauchamps, who was chief of the presidential press service between 1974 and 1976. In Dijon and Marseille, former rightist politicians were heading the regional television stations.

Other signs of this symbiotic relationship were a strong national monopoly at the expense of the freedom of television and radio coverage and regional coverage. This stemmed from General de Gaulle's desire to curb the regional notables' power, however, his policy failed. The only exception was Radio France, which introduced both pluralism and true local news. The 1982 law decentralizing the media further entrenched the power of notables, who now had no need to be accountable to anyone. While regional reporters have some autonomy, local reporters are often chosen by the local officials, especially the mayor's office. Local journalists are very dependent on local power and reluctant to engage in polemics, and thus less critical of the mayoral office in particular.

State Subsidies

In 2001 direct subsidies totaled approximately 260 million francs, a 2 percent decrease over 2000 subsidies. The many forms and levels of subsidies form a complicated structure almost incomprehensible to the uninitiated eye, but they can be separated into direct and indirect subsidies. Among the main direct subsidies are subsidies for the national and regional dailies with low publicity revenues, transportation subsidies, subsidies for facsimile transmissions, subsidies for the expansion of the French press abroad, and subsidies for the multimedia. Since the Liberation, the government has subsidized the daily press, whether it is national or regional, departmental or local. In order to qualify a newspaper must limit its publicity revenues to 30 percent of its turnover. These provisions are updated regularly, two major updates taking place in 1986 for the national press, and in 1989 for the regional, departmental, and local press. New revisions in October 2000 benefited L'Humanité which had been penalized. The fund to promote the French press abroad was updated in February 1991 while on November 6, 1998 the fund for the transportation of the press was updated.

Among the indirect subsidies are subsidies for social expenses, professional membership fees, subsidies for postal transportation, preferential VAT treatment, cancellation of the professional and social contribution taxes, and a host of other measures. Those subsidies are voted yearly, with eligibility and other provisions being regularly revised. Thus reduced postal rates were last revised as per a decree of January 17, 1997.

The Finance Law of 1998 not only redirected those subsidies but created a modernization fund for the daily political and general press. In 1998-99, the amount of subsidies increased significantly, as seen in a Multimedia Development Fund offering of up to 305,000 Euros in 1999 to specific projects (or 30 percent of expenses), with a total allocation fund of 2.3 million Euros in 1999. As of 1999, approximately thirty newspapers had availed themselves of the fund, including Le Figaro , FranceSoir , Le Nouvel Observateur , PhosphoreLe Télégramme de Brest, and La Charente Libre . Other media sectors encouraged to go on line and use multimedia supports open to the public included the Institut National de l'Audiovisuel which stored television and radio programs; and radio and television programs, including RFO (Radio France Outremer) and the ensemble of the Radio-France stations broadcast online since 1999.

In the late 1990s, the French government created many subsidies for the new technologies. By a decree of February 5, 1999 the government further amended the provisions of the Ordinance of November 2, 1945 regarding the modernization of the press. Subsidies and loans were granted by an employer-employee Orientation Committee up to 40 percent of the expenses and 50 percent for collective projects, dealing with productivity increase, reduction of production costs, improvement and diversification of the reactionary format through the use of modern technologies (for acquiring, storing, and diffusing information), and reaching new categories of readers. A Control Commission was charged with overseeing the projects' execution. The RIAM (Réseau pour la Recherche et l'Innovation en Audiovisuel et Multimédia), launched in 2001, which coordinates the planning or research, or the Fonds Presse et Multimédia, created by the DDM in 1997 which purports to help increase public access to newspapers, magazines and journals on digital supports in both their on-and off-line formats.

Press distributors receive a graduated fee for their services as per a decree of February 9, 1988. In the late 1990s, given the increase in distribution costs, they were pressured to diminish their fees. The government, however, in 2000 refused to change a provision limiting a decrease of the fees to one percent for dailies and two percent for all other periodicals. In 2001, the fee was increased from 9.5 percent to 19.5 percent depending on the work conditions, in order to encourage the 15,000 of them. Provisions were also made to allow them to limit the bulk sent to them if supplies exceeded sales, and to help them computerize their sales transactions in order to better manage their business. Provisions were also made to continue the low rates of health insurance coverage of press distributors and local correspondents who have enjoyed them since 1993.

The AFP received in 2001 a 100 million FF governmental loan to help diversify its activities, services, and products. Stating that the clients are becoming more diversified, international and professional, and that their products will include photos, infography, and databases, the AFT foresaw a 2001 budget of 1.621 billion FF, with state subscriptions increasing by two percent for a total of 619 million FF. AFP is in full expansion, foreseeing a growth rate of seven percent between 2001 and 2004.

The government also took measures to help recycle old papers, of which the printed press makes a considerable amount, 2.65 million tons produced in 2000. An estimated 40 percent of that amount could be recycled, according to a study conducted in 2001.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

Accreditation Procedures for Foreign Correspondents

Foreign correspondents from countries outside the European Union whose stay in France exceeds three months must obtain residency permits from the French government and complete accreditation procedures with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. If they cover presidential press conferences, they must join the presidential press association. The Foreign Affairs Ministry has created a site called CAPE or Centre d'Accueil de la Presse Etrangére to assist foreign journalists with short term missions, inform foreign correspondents and media of all conferences or programs by domestic or foreign personalities, and facilitate meetings of representatives of the foreign media.

There is no screening of cables or censorship of foreign media. Import of periodicals must get approval from the Ministry of Commerce. All major international press organizations are represented in France who voted against restrictions on newsgathering in support of the UNESCO Declaration of 1979. Distribution of foreign propaganda is strictly forbidden.

France is known for its support of human rights and freedoms. It extends this support to foreign journalists in any part of the world. Thus in the 1990s, the French press denounced the loss of freedom of the press in Islamic countries, in particular the Maghreb (Tunisia, in 1997), the expulsion of press correspondents, the closing of opposition newspapers, and noted the ouster in 1996 of the Tunisian Newspaper Directors' Association from WAN.

Foreign Newspapers in France

There are a great number of foreign news publications in France, starting with the press services of foreign countries, of institutions such as the United Nations and the European Community, World Bank, and IMF. There are 45 offices representing German newspapers, radio and television stations, including a Paris representative of financial and economic newspapers such as the Financial Times -German edition, or Tomorrow Business , and a correspondent of RTL-TV-Deutschland. England has 17 foreign correspondents in France. Belgium has 10 correspondents, Spain 22, including a CNN representative, Italy 23, Poland 9, Russia 11, Switzerland 19, China 11, Japan 17, Vietnam 3, and the United States 32. All African countries together have 6 foreign correspondents, mostly from French-speaking countries (Ivory Coast, Gabon, Madagascar, Cameroon, and South Africa), and the main American TV stations such as CNN and CBS are broadcast in France.

France imports significant amounts of foreign newspapers. In 1995, the amount of press imports almost equaled the amount of press exports, in million dollars, 550 against 446. The issue foreign media access may soon be a moot point. Most Internet sites already give access to selected foreign media, while some sites such as Courier International offer a world guide of the online press.

There are 33 international press and media professional organizations in France. Some are completely international, such as the World Association of Newspapers (WAN) while others are a partnership between France and another country (Russia, Japan, Poland). Some represent a region (Asia, Europe, Africa) while others are thematic (education television stations, environment), or regroup media genres (independent and local radio and television stations, audio-visual and telecommunications media), or professional categories (editors-in-chief, journalists). Some are sponsored by France, such as the Centre d'Accueil de la Presse Etrangére sponsored by Radio France, the CRPLF or Communauté des Radios Publiques de Langue Française, or Reporters Sans Frontiéres.

The International Herald Tribune is probably the most distinguished foreign newspaper in France. It is produced in Paris and printed in 24 press centers across the globe, mostly in Europe and Asia, by a total staff of 368, of which 56 are journalists. Since its beginning in 1887 as the New York Herald Tribune, it has engineered a series of journalistic and technological "firsts," none as spectacular as its successful transition from a traditional newspaper to a cross-media brand since 1978. These strategies paid off as IHT increased its circulation by 35% between 1996 and 2001, during which its sold 263,000 copies for a readership of more than 580,000 worldwide. The secret to its success lies in its ability to deliver world news in a concise format (24 pages), its commitment to excellence, and its independence. Owned jointly by the Washington Post and the New York Times since 1991, it was the first newspaper in the world to be transmitted electronically from Paris to Hong Kong in 1980, thus becoming available simultaneously to readers across the globe. It has also set up joint ventures with leading newspapers in Israel, Greece, Italy, South Korea, Japan, Lebanon, and Spain and publishes (in English) local inserts that contain domestic news. Calling itself the world's daily newspaper, it is perceived as the most credible publication by its upscale, mobile, international readership.

Small foreign newspapers are produced in France, such as Ouzhou Ribao , a Chinese language newspaper owned by the Taiwanese press group Lianhebao-United Daily News, which contains general information for Asia about Europe.

Foreign Ownership of Domestic Media

Foreign ownership of domestic media or foreign partnerships in domestic media is a reality within the framework of the European Union. An example of foreign ownership of domestic media is Les Echos , owned by the British group Pearson. Olivier Fleurot, who directed the Les Echos group from 1995 to 1999, was named in 1999 general director of the Financial Times , which he planned to turn into the premier world financial and economic newspaper. The Italian press group Poligrafici Editoriale owns France-Soir . The Sygma photo agency founded in 1973 by Hubert Henrotte was bought in June 1999 by Corbis, which is owned by Bill Gates.

With the internationalization of the media in the Information Society, joint partnerships and transnational groups are bound to increase, thus blurring the distinction between foreign ownership and domestic media. The European Community has already made European television a reality with its European Convention on Transfrontier Television, which France accepted in 2002. The Arte television station is enjoying a great success in its two sponsoring countries, France and Germany, and is fast gaining a European audience. Internet groups are the most transnational thus far.

The Francophone Press and French Media Abroad

The French-speaking press has known a considerable increase in the 1990s, in great part around the Mediterranean rim. French-speaking media are diffused on all continents: in Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland, Canada, Quebec, Haiti, and Louisiana as well as in Lebanon, Algeria, Benin, Ivory Coast, Morocco, Niger, Senegal, Togo, Tunisia, and several other African countries.

RFO (Radio France Outremer) and the ensemble of the Radio-France stations broadcast online since 1999. Radio France International had broadcasts in French, English, Portuguese, Spanish, and Chinese every 30 minutes in addition to daily and weekly press reviews in French, English, Spanish, and German. TV5, an international television station, broadcasts on all continents; its online version features useful and local information. The television organization TVFI was charged with promoting French television programs abroad and was charged by the Foreign Affairs Ministry to offer online program offers, a repertory of French production associations, and in general to promote French programs. To further Fran-cophone programs, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs offered a Fonds Sud Télévision to help public and private television stations in "priority solidarity zones" including sub-Saharan Africa in 2002.

All the initiatives taken by CISI have tended to develop online initiatives while putting information and communication technologies at the service of the promotion of the French language. Again, education, culture, and media are inseparable in this perspective. In addition, the educational Réseau Théophraste encourages and finances projects that develop both the media and fran-cophonie.

News Agencies

The Agence France Presse remains one of the main French news agencies. Founded in 1835 by Charles-Louis Havas, it was the first world news agency. In 1852, a publicity branch was created. In 1940, the publicity and information branches separated and the Office Français d'Information was born. In 1944, journalists who had participated in the Resistance rebaptized the agency AFP and gave it a new statute. In 2000 a bill was introduced in the Senate to modify this statute, but it did not pass. From the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s, important changes took place: creation in 1984 of an audio service, creation in 1985 of regional production and diffusion centers in Hong Kong, Nicosia and Washington, and creation of the international photo service, enlargement of the Nicosia regional center in 1987, where the Cairo desk was transferred, launch of an English financial news service, AFX, in 1991.