Honduras

Basic Data

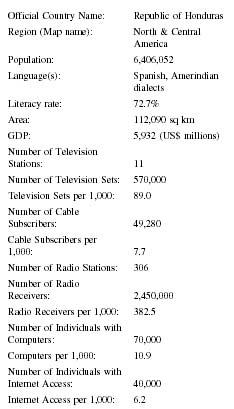

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Honduras |

| Region (Map name): | North & Central America |

| Population: | 6,406,052 |

| Language(s): | Spanish, Amerindian dialects |

| Literacy rate: | 72.7% |

| Area: | 112,090 sq km |

| GDP: | 5,932 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Television Stations: | 11 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 570,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 89.0 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 49,280 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 7.7 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 306 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 2,450,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 382.5 |

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 70,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 10.9 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 40,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 6.2 |

Background & General Characteristics

Originally part of Spain's empire in the New World, the Republic of Honduras was freed from Spain in 1821. After briefly being annexed to Mexico, in 1823 Honduras gained its independence and joined the newly formed United Provinces of Central America. After the collapse of the United Provinces in 1838, Honduras continued its foreign policy to unite Central America until after World War I.

U.S. companies controlled Honduras's agriculture-based economy during the twentieth century after U.S. businesses established large banana plantations along the north coast. Not long after World War II, provincial military leaders gained control of the Nationalists and the Liberals, the two main Honduran political parties. Two authoritarian administrations and a strike by banana workers paved the way in the mid-1950s for a palace coup by military reformists.

In 1957, constituent assembly elections took place and a president was elected. The assembly also transformed itself into a national legislature. From 1957-63 the Liberal Party ruled Honduras. Then in October 1963 conservative military officers deposed the president in a bloody coup. For a brief time in the early 1970s a civilian president was in charge until his administration was the victim of a coup in 1972. For the next 11 years, military men ruled Honduras. In April 1980 a constituent assembly was elected and general elections took place in November 1981. A new constitution was approved in 1982 and a Liberal Party president took office after the free elections.

In January 2002, President Ricardo Maduro of the National Party took office, becoming Honduras's sixth democratically elected president since 1981. He inherits a nation where it was estimated at the turn of the twentieth century that 85 percent of the 6.4 million Hondurans live below the poverty line, and the average annual income is U.S. $850.

Honduras's capital is Tegucigalpa. The national language is Spanish, although English is often spoken in the Bay Islands. The approximate 112,000 square kilometers of land varies from primarily mountains in the interior to narrow plains along its 820 kilometers of coastline, including the almost inhabitable eastern Mosquito Coast along the Caribbean Sea. Honduras's neighbors are Nicaragua, El Salvador and Guatemala, with a long stretch of coastline facing the Caribbean Sea and a small stretch on the opposite side of the country along the North Pacific Ocean.

In 1998 Honduras was devastated by Hurricane Mitch, which killed around 5,000 Hondurans and destroyed about 70 percent of the nation's crops. The hurricane set back the nation's development by several decades.

Not all of Honduras's problems can be blamed on the weather. Poor housing, youth gangs, crime, malnutrition, allegations of police wrongdoing, and the murder of indigenous rights groups allegedly by right-wing paramilitary groups, plague the nation.

Honduras has suffered almost 300 internal conflicts—rebellions, civil wars and changes of administrations—since gaining its independence. More than half of those conflicts have occurred in the twentieth century. With this type of history, it is no wonder that the strict defamation laws shackle Honduran press. At times the press in Honduras is its own enemy, as journalists have been known to practice self-censorship to avoid offending the interests of media owners, and accept bribes from officials in return for favorable coverage.

Nature of the Audience

More than 54 percent of Honduras's population is between the ages of 15 and 64 years, while another 42.22 percent is 14 years old or younger. In 2001, population growth was estimated at 2.34 percent annually, with a life expectancy of 69.35 years (67.51 years for men, 71.28 years for women). However, these estimates must take into consideration the country's high incidence of HIV/AIDS. From 1990 to 1996 Honduras reported 5,902 AIDS cases and another 3,132 people with HIV (the virus that causes AIDS), according to the Health Ministry.

Of the Honduran population, 72.6 percent of the men and 72.7 percent of women are literate, which is defined as those aged 15 and over who can read and write. Around 90 percent of the population is mestizo (mixed Amerindian and European), about 7 percent is of Amerindian descent, 2 percent is black and 1 percent is white. The overwhelming majority of Hondurans (97 percent) are Catholic, with the remainder primarily Protestant.

General Media Characteristics

Honduras supports six major newspapers, with most based in Tegucigalpa. There are five national dailies, three of which— El Periodico, La Tribuna and El Heraldo —are headquartered in Tegucigalpa, as is the weekly English-language newspaper Honduras This Week. The other two dailies, El Tiempo and La Prensa, are based in San Pedro Sula. The government publishes its decrees in the weekly La Gaceta.

Political figures are a prominent part of the Honduran press. Former President Rafael Leonardo Callejas is the principal stockholder in El Periodico , and the paper is known for its conservative views.

Another influential political figure, Jaime Rosenthal, owns El Tiempo. Rosenthal, a Liberal Party leader who finished second in the Liberal Party of Honduras primary for the 1993 national election, leads the more liberal paper, which is known to criticize the police and military. As a result, the editor, Manuel Gamero, has at times been jailed.

La Tribuna and La Prensa are considered by most press observers to be more centrist than the others, although some would say La Prensa is a little more to the right of center. La Tribuna is owned by yet another political figure, Carlos Flores Facusse, who in 1989 made an unsuccessful bid for the presidency before being elected to that post in the November 1997 election. La Tribuna has close ties to the Liberal Party and to Tegucigalpa's industrial sector.

La Prensa has ties to San Pedro Sula businesses, as well as other publishing interests. Publisher and editor Jorge Canahuati Larach is a member of the family that also publishes El Heraldo. That paper is more conservative than La Prensa, and has been more favorable in its coverage of the military than other dailies. El Heraldo often reflects the positions of the National Party.

Daily newspapers reach about 159,000 readers, but Honduras also has smaller publications. The most significant of those—the monthly Boletin Inforativo —is published by the Honduran Documentation Center (Centro de Documentacion de Honduras, or CEDOH), run by the respected political analyst Victor Meza.

CEDOH and the Sociology Department at the National Autonomous University of Honduras (Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Honduras, or UNAH) publish Puntos de Vista, a magazine centering on social and political analysis. In addition, Honduras This Week covers national news and events in Central America.

Honduras's major newspapers are all members of the Inter American Press Association (IAPA), which was set up in 1942 to defend and promote the right of people of the Americas to be fully and freely informed through an independent press, according to information obtained from the IAPA. In March 2001, the IAPA announced its support for and adherence to the Declaration of Principles on Freedom of Expression during a ceremony in Washington, D.C., chaired jointly by Cesar Gaviria, secretary general of the Organization of American States, and IAPA President Danilo Arbilla.

The declaration was drafted by the Organization of American States's (OAS) Inter American Commission on Human Rights. Gaviria called it a "significant contribution to the establishment of a legal framework to protect the right to freedom of expression." He also said it would "surely be the subject of interest and study by OAS member countries." The document includes 13 principles of freedom of expression and is based on the Declaration of Chapultepec, sponsored by the IAPA and drafted in 1994. Honduras signed that declaration in July 1994, under then-President Carols Roberto Reina.

The Declaration of Principles on Freedom of Expression was adopted at the 108th regular session of the Inter American Commission on Human Rights in October 2000, and submitted for the approval of OAS member countries during a general assembly in Quebec, Canada, in April 2001.

Several periodicals are published in Honduras, as are a number of trade papers. One popular periodical is Coconut Telegraph, which features stories on vacations and travel.

Private interests own around 80 percent of newspapers. All Honduran television stations are privately owned. The government owns the radio station Radio Honduras. There is no national news agency.

Economic Framework

In 2000, Honduras was generally seen as one of the poorest nations in the Western Hemisphere. It is basing much of its hopes for the future on expanded trade privileges under the Enhanced Caribbean Basin Initiative and on debt relief under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries initiative.

Honduras has come back from much of the economic problems caused by Hurricane Mitch, and the gross domestic product in 2001 rose an estimated 5 percent. The labor force in 1997 was estimated at around 2.3 million. Of that labor force, about 50 percent were employed in services, agriculture employed 29 percent and industry around 21 percent, according to 1998 figures. However, in 2000 it was estimated that Honduras had an unemployment rate of 28 percent.

The Honduran economy is rebounding, and in 2001 it grew 2.5 percent, according to the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. Inflation was at 9 percent in 2001, slightly lower than the previous year.

Press Laws

The 1982 Honduras Constitution guarantees freedom of the press. However, with the news media concentrated in the hands of a small number of powerful businessmen, as well as local businessmen or their close family members, press laws are not always respected.

The Law of Free Expression of Thought came into effect Aug. 26, 1958, when it was published in La Gaceta, the official bulletin, according to the Inter American Press Association. Article 1 of that law states: "No person may be harassed or persecuted for their opinions. The private actions that do not alter public order or that do not cause any damage to third parties are outside the action of the Law." According to the first part of Article 2: "The freedoms of speech and of information are invio-late. This includes the right to not be harassed for one's opinions, to investigate and receive information, and to disseminate it via any means of expression."

However, according to Article 6: "It is forbidden to circulate publications that preach or disseminate doctrines that undermine the foundation of the State or of the family, and those publications that provoke, incite to or encourage the commission of crimes against persons or property." Clearly this leaves room for interpretation regarding what or what does not undermine the state or the family.

Honduran journalists also must adhere to the Organic Law of the College of Journalists of Honduras, an obligation that went into effect on Dec. 6, 1972. That law is, in effect, a mandatory licensing law for journalists and the OAS's Inter American Court of Human Rights has found that mandatory licensing laws such as this violate the American Convention on Human Rights. According to the OAS's Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression, the College of Journalists has become an "organization that restricts freedom of expression and limits the free practice of journalism."

The law requires that all Honduran journalists have a valid degree in journalism, be registered in the College of Journalists, and that editors, managing editors, editors-in-chief and news editors be Honduran by birth. If a journalist is caught practicing the profession without being a member, he is fined, as is the person or company that contracts the offender's services. The College of Journalists also is responsible for sponsoring courses to upgrade the profession.

The College of Journalists is charged with overseeing the regulation of professional journalism, and according to Article 2e, "To cooperate with the State in the fulfillment of its public functions."

Foreign journalists must abide by a strict set of laws in order to practice their profession in Honduras. Article 18 of the Organic Law mandates that foreign journalists must comply with immigration, labor laws and treaties of Honduras; have their degree revalidated at the National University of Honduras, and register with the College of Journalists.

Honduran journalists must also worry about criminal defamation laws. Article 345 of the penal code mandates jail sentences of two to four years for anyone who "threatens, libels, slanders, insults or in any other way attacks the character of a public official in the exercise of his or her function, by act, word or in writing." Under Article 323, anyone who "offends the President of the Republic" may be sentenced to up to 12 years in prison.

Defamation is a criminal offense, and those found guilty may receive up to a year in prison, although no prosecutions were reported in 1999. Although defamation laws have been reformed, lawsuits remain a risk. Many officials still use any available legal means to stifle criticism in the press. Some government and corporate sponsors have been known to retaliate against the press by discriminately doling out advertising dollars, according to information provided by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). In a nation trying to rebound economically, this is a particularly devastating and effective tactic.

In 2001, a government-proposed bill that would have tackled organized crime was presented to parliament. The bill (Article 7) stated "professional confidentiality cannot be cited as a reason not to cooperate" with government officials, according to Reporters Without Borders. The bill would have made it easier to tap telephones and intercept postal or electronic mail. In addition, a new penal code (Article 372) would mandate between four and seven years in prison for revealing a state secret. Although neither bill was approved by the end of the year, the fact they were put forward by the government clearly sends a message to the press.

Censorship

In theory, the rights of the press generally are respected. In practice, they sometimes appear to be breached. The media is subject to corruption and politicization, and there have been instances of self-censorship, allegations of intimidation by military authorities, and payoffs to journalists, according to a 1992 U.S. Department of State human rights report.

In a press scandal that became public in January 1993, a Honduran newspaper published information contained in documents belonging to the National Elections Tribunal (Tribunal Nacional de Elecciones) showing payments to 13 journalists. Many observers believed at the time that more than half of journalists received payoffs for stories, some from government institutions including municipalities, the National Congress, various ministries and the military.

Another problem has been self-censorship in reporting sensitive subjects, particularly issues concerning the military and national security, according to the U.S. State Department report. Intimidation, threats, blacklisting and violence also occurred at various times in the 1980s and early 1990s.

Some analysts say that despite instances of military intimidation of the press in early 1993, print and broadcast media played an important role in creating an environment conducive to the public's questioning and criticism of authorities. Honduran sociologist Leticia Salomon said that in early 1993 the media, including newspaper caricatures, played "an instrumental role in mitigating the fear of criticizing the military." He believes this diminishment of fear was an important step in the building of a democratic culture in Honduras.

Little investigative journalism is done in Honduras, and when it does occur the focus primarily is on non-controversial subjects, according to the U.S. State Department. If a journalist does try to do an in-depth report, the reporter is faced with external pressure to halt the investigation, restrictive deadlines, and often a lack of access to government documents or independent sources.

State-Press Relations

As the twentieth century came to a close and the twenty-first century opened, freedom of the press in Honduras remained a difficult goal. Restrictive government policies were targeted toward silencing the independent media and corruption among journalists.

Independent journalists often faced government pressure, according to a 1999 CPJ report. Phones were often tapped, the "established" press often ridiculed them, and fear was ever present. One San Pedro Sula television journalist, Rossana Guevara, told police she had been harassed after looking into cases of government corruption. And in July 1999, someone tried to kidnap another television journalist, Renato Alvarez of Telenisa Canal 63, after he reported details of a possible coup.

In 2001, Reporters Without Borders characterized Honduras's media situation as "tense." A half dozen journalists in total were dismissed from the newspaper El Heraldo and the television station Canal 63, with all six claiming the government pressured their employers. Allegations of intervention were also leveled against former President Flores.

The Journalists Institute suspended dozens of its members in 2001. It also criticized two outspoken journalists who voiced objections against the institute's decisions and corruption among their colleagues.

The Honduran government installed in January 2002 may not try to control the press as much as past administrations have, according to the Inter American Press Association. However, threats and legal matters remain in the way of a totally free press.

The deputy of Democratic Unification, the left-wing party, has asked the National Congress to regulate press freedom, including controlling journalists and media outlets. His request was based on a recently published case in which the U.S. Embassy suspended the visas of three prominent Honduran businessmen.

The independent press also faced pressure from the government of former President Flores. The press gave prominent coverage to the more powerful politicians during the November 2001 presidential elections. Small political parties received little or no coverage and had little or no access to the media. Meanwhile, the National Party and the ruling Liberal Party flooded radio and television stations with advertisements. National Party candidate Ricardo Maduro won the race, defeating Liberal Party candidate Rafael Pineda Ponce, to become president.

It can frequently be difficult to distinguish the media from the politicians in Honduras. Former President Flores owns La Tribuna. In addition to El Tiempo, Rosenthal owns a television station, Canal 11. Other politicians are reported to own radio and television stations, according to CPJ.

The government in 2001 reportedly influenced the decision of El Heraldo, traditionally known for its anti-government stances, to fire opinion editor Manuel Torres and a reporter, Roger Argueta, according to CPJ. A month earlier the paper lost editor Thelma Mejia when she resigned, also reportedly under government pressure. All three had criticized the government while working at the paper. After they left, the newspaper's coverage of the Flores administration became decidedly less critical.

In September 2001, former President Flores pledged to ensure no limits are placed on press freedom after a meeting with an Inter American Press Association delegation, a meeting during which the issue of legislation to force journalists to disclose their sources of information was raised. Flores assured the delegation he would act to remove any provision that would curtail freedom of the press. In doing so, Flores cited his own newspaper background, from being editor of the daily La Tribuna to actually owning the paper. At the end of the year, the legislation—still with the provision—had not been acted upon.

The military allegedly has been involved in intimidating members of the press. In January 1993, an El Tiempo reporter, Eduardo Coto, witnessed the murder of a San Pedro Sula businessman. When El Tiempo 's business manager gave refuge to Coto, a bomb exploded at his home. Coto had alleged that the businessman was killed by members of Battalion 3-16, a military unit suspected in the disappearances of several people in the 1980s. Coto is said to have received death threats from members of the military. He fled to Spain, where he was given asylum.

Under the Maduro administration, many observers hope that the press will be freer than it has under previous governments. Whether that turns out to be the case or not will be determined in the coming years.

Broadcast Media

Radio Honduras is owned by the government, but the state does not own a television station. Honduras has around 290 commercial radio stations broadcasting on about 240 AM stations and 50 FM stations. Hondurans own about 2.45 million radios, according to 1997 U.S. government figures.

Honduras has nine television channels, with an additional 12 cable television stations broadcasting to approximately

Electronic News Media

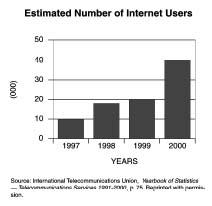

As of 2000, Honduras had eight Internet service providers, according to U.S. government figures. Honduras also reported around 40,000 Internet users. About 12 television stations air programs on the Internet, as do around 25 AM and FM radio stations, as well as several newspapers and other publications.

Education & TRAINING

The Inter American Press Association established a scholarship fund in 1954 for young journalists and journalism school graduates. The scholarship allows U.S. and Canadian scholars to spend one academic year studying and reporting in Latin America and the Caribbean. In return, Latin American and Caribbean students spend an academic year at a recognized U.S. or Canadian journalism school. Member publications and private foundations help support the fund, and no government funding is accepted.

The primary institution of higher education in Honduras is the National Autonomous University of Honduras (UNAH), which was founded in 1847. It has around 30,000 students, with branches in San Pedro Sula and La Ceiba.

Three private universities are located in Honduras, although most observers believe UNAH remains the top educational choice. The tiny Jose Cecilio del Valle University is located in Tegucigalpa, as is Central American Technological University. The third private university is the University of San Pedro Sula. Annual enrollment in higher education in Honduras is around 39,400 students.

Summary

Although its history might not appear to leave much hope for a completely unfettered and free press, Honduras has made progress. Some see greater hope for a freer press under the leadership of President Maduro, although that has yet to be proven.

Ownership of newspapers by politicians and government officials does not do much to help freedom of the press, and the kinds of harassment reported by those who criticize the government further erodes the possibility of a free press in Honduras. In addition, restrictive laws such as those requiring journalists to belong to the College of Journalists-in effect, a licensing law-further inhibits a free press. The government's pressure on the press also shackles journalists. The press in Honduras will not be free until these pressures on the media are removed.

Significant Dates

- 1982: The Honduran Constitution guarantees freedom of the press.

- 1998: Hurricane Mitch devastates the country.

- September 2001: Honduran President Carlos Flores pledges to ensure no limits are placed on press freedom in his country.

Bibliography

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). The World Fact Book 2001. Available from http://www.cia.gov .

"Country Profile: Honduras." BBC News, July 20, 2002. Available from http://news.bbc.co.uk .

"Country Profile: Honduras." Available from http://www.worldinformation.com .

"Freedom of the Press Report 2002." Country Reports. The Committee to Protect Journalists. Available from http://222.cpj.org .

"Honduras." Country Reports. The Committee to Protect Journalists. Available from http://www.cpj.org/index.html .

"Honduras." Press Laws Database. Inter American Press Association. Available from http://216.147.196.167/projects/laws-hon.cfm .

"Honduras: Constitutional Background." Library of Congress Country Study, 1992. Available from http://www.lcweb2.loc.gov .

"Honduras: Economic and Political Overview." In Latin Business Chronicle. Available from http://www.latinbusinesschronicle.com/countries/honduras/ .

"IAPA in Honduras defends professional secrecy, rejects licensing of journalists." Inter American Press Association, September 7, 2001.

Reporters without Borders. "Honduras: Annual Report 2002." Available from http://www.rsf.fr .

U.S. State Department. "Honduras." In Consular Reports. Available from http://www.state.gov .

World Press Freedom Review. International Press Institute. Available from http://www.freemedia.at .

Brad Kadrich

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: