Haiti

Basic Data

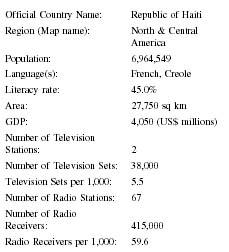

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Haiti |

| Region (Map name): | North & Central America |

| Population: | 6,964,549 |

| Language(s): | French, Creole |

| Literacy rate: | 45.0% |

| Area: | 27,750 sq km |

| GDP: | 4,050 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Television Stations: | 2 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 38,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 5.5 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 67 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 415,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 59.6 |

Background & General Characteristics

Haiti is part of an island located in the Caribbean; it occupies the western one-third of the island of Hispaniola, between the Caribbean Sea and the North Atlantic Ocean, west of the Dominican Republic. The country gained its independence from France in January 1804. Haiti's Constitution was approved in March 1987 then suspended in June 1988; Haiti returned to constitutional rule in October 1994.

As of 2002, the president was elected by popular vote to five-year terms. The prime minister was appointed by the president, and then that appointment was ratified by the Congress. The Senate had 27 seats, with members serving six-year terms. One-third was elected every two years. The Chamber of Deputies had 83 seats, and members were popularly elected to serve four-year terms.

The total population in Haiti in 2002 was estimated at nearly 7 million, with a 1.7 percent growth rate. While the birth rate is at 31.4 per 1,000 people, the infant mortality rate is a staggering 93.3 per 1,000, nearly 10 percent. More than 55 percent of the country's population is between the ages of 15 and 64; another 40.31 percent are 14 years old or younger. Blacks make up 95 percent of the population, with the other 5 percent mulatto and white. The vast majority of Haitians (80 percent) are Roman Catholic. French and Creole are the official languages.

While the Haitian Constitution actually provides for freedom of the press, putting the theoretic rights into practice was not necessarily a safe thing for journalists to do, especially in the early 2000s. The country supported several newspapers. Haiti Progress , the largest Haitian weekly publication, was published in French, English, and Creole every Wednesday.

As of 2002, the Haitian Times was the only full-color weekly newspaper distributed in the Haitian community and in Haiti. The Times was the only Haitian-American newspaper with full-time professional journalists. It covered Haitian and Haitian-American news; arts and leisure; entertainment, reviews, profiles and social events. Regarding sports, it covered Haitian and American soccer, basketball, and tennis. Its columns cover news from Boston, New York, and Miami, in addition to Haiti. The Times had a pool of award-winning writers and photographers both in the United States and in Haiti, and they were known for their authority on Haitian and Haitian-American issues.

Journalists in Haiti have long been subject to attacks, particularly by mobs on one side or another of a particular issue. In what Amnesty International called "one of the most high-profile acts of violence in recent Haitian history," prominent radio journalist and long-time democracy and human rights activist Jean Dominique was shot to death by an unknown assailant outside the courtyard of his radio station, Radio Haiti Inter. A station guard, Jean Claude Louissaint, was also killed in the attack, which occurred April 3, 2000.

Jean Dominique's death was a serious blow to Haiti, according to Amnesty International, largely because he had been such an outspoken advocate for change throughout the turbulent previous four decades in the country's history. His radio broadcasts were the first to be done in Creole rather than French, and they created an unprecedented forum for critical thought. The key was that it did so not only for the country's "educated elite," but also for Haiti's poor population, which was considerable at the beginning of the twenty-first century.

Dominique had survived imprisonment under dictator Francois "Papa Doc" Duvalier, who came to power in 1957. He was forced into exile during the reign of Jean Claude "Baby Doc" Duvalier, who succeeded his father in 1971, and again after Haiti's military coup in 1991. Subsequently, a United Nations peacekeeping force helped restore democratic rule to Haiti and restored President Jean-Betrand Aristide to office. But even after that return to constitutional order in 1994, Jean Dominique was not satisfied, pointing out anti-democratic tendencies within diverse sections of the Haitian political and societal scenes. Haitians were stunned, according to Amnesty International, by the fact such a pillar of democracy could be gunned down by an unidentified killer, after surviving so many conflicts where his adversaries were known.

Acts of violence, particularly killings, where journalists are involved regardless of their political views have a far-reaching effect on society. As noted by the Organization of American States Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression, the American Convention of Human Rights— which counts Haiti among its members—requires states to investigate effectively the murder of journalists and punish the perpetrators of such acts.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) said the lack of "an effective and thorough investigation into any criminal sanctions against the primary parties involved—and their accessories—is particularly serious because of its impact on society." When such crimes go unpunished, not only are all other journalists practicing their craft in the country intimidated, but also it has a detrimental effect on all citizens, who become afraid to report mistreatment, abuse or any other kinds of unlawful acts.

The case of the murder of Jean Dominique led to widespread questioning of the human rights situation in Haiti, even seven years after the restoration of the democratic government in Haiti. Even more significant, according to Amnesty International, was the fashion in which the investigation hit roadblocks and obstacles that illustrated the lack of human rights in Haiti. The obstacles have included lack of independence of the police force and the justice system; the failure of those institutions to confront ruling-party activists responsible for threats and much of the political violence; and acts of violence committed under the auspices of elected officials.

Even more troubling, it would seem from a journalistic standpoint, were the climbing number of attacks on journalists in the two years following the death of Jean Dominique. These started almost immediately and changed, perhaps forever, the climate in which journalists try to do their jobs in Haiti. For example, the same night Jean Dominique was killed, radio station Radio Unite, based in St. Michel de l'Attalaye, was sacked and part of its equipment stolen shortly after reporting Dominique's death. The station had reportedly received threats earlier.

Jean Dominique was buried April 8, 2000. After the funeral, pro-Famni Lavalas (FL) groups set fire to the office of Konfederasyon Inite Demokratik (Democratic Unity Conference), which served as headquarters to the opposition coalition. They also threatened to burn down private radio station Radio Vision 2000, which is critical of the Aristide government. Furthermore, on May 3, 2000, in Place in the Department of the South, community station Radio Via Pelican Sid (Voice of the Peasant Farmers of the South) was sacked. The station had reportedly already received threats. Journalist Adulate Guedeouengue, who was abducted, beaten and robbed in May 2001, was reportedly looking into Dominique's murder at the time of his attack and had been told by his kidnappers to stop investigating.

The Guedeouengue case was a perfect example of how much pressure the media faced in the aftermath of the murder of one of its biggest Haitian stars. Other Radio Haiti Inter journalists reported threats, harassment, and intimidation, including those done by people who were believed to be police. On December 15, 2000, a 34-year-old sports reporter for Port-au-Prince Radio Plus, Gerard Denoze, was shot and killed by a pair of unidentified assailants while stepping out of a car in Carrefour. The Association Haitienne de la Presse Sportive (Haitian Sports Press Association) said he had been receiving death threats for some time.

On December 27, 2000, the Port-au-Prince private radio station Radio Caraibes FM suspended its broadcast temporarily because it received threatening letters and telephone calls. It also reportedly received direct threats to individual journalists within its organization. The threats were allegedly made by members of popular organizations close to FL.

In January 2001, Paul Raymond, leader of Ti Kominite Legliz, a popular organization close to the FL, publicly threatened some 80 journalists, clerics, and politicians if they did not support the party. Moreover, the director of information for the Port-au-Prince-based radio station Signal FM reportedly received death threats over three days in June 2001 for questioning the behavior of some of FL's influential senators.

Later that month, on June 20, a Radio Haiti Inter broadcaster said he was followed, forced out of his automobile and threatened by two armed men. The men claimed they were police, and that they recognized the car as having belonged to Jean Dominique, the murdered director of Radio Haiti Inter. The Haitian National Police denied any of its officers had been involved, but acknowledged the men may have been ex-police. The radio station lodged an official complaint but, of course, never heard back.

On July 28, 2001, Radio Rotation FM reporters Reynald Liberus and Claude Francois did interviews with some of the alleged perpetrators of a series of attacks on police stations around Port-au-Prince. According to sources, they were allegedly arrested without warrants and mistreated by police, who were reportedly trying to get tapes of the interviews.

Jean Ronald Dupont, a journalist for Radio Maxima FM, sustained wounds to the head October 2, 2001, while covering a demonstration in Cap Hatien, the country's second largest city. The wounds were reportedly suffered when police fired at shoulder level in an attempt to disperse crowds. That same day, another radio reporter, Radio Metropole correspondent Jean-Marie Mayard, was assaulted in St. Marc, department of the Artibonite, by members of a popular organization. The attackers broke Mayard's tape recorder and threatened to kill him if he did not stop broadcasting reports critical of the Lavalas Family political party.

To close out what was a tough month for journalists, Radio Haiti Inter journalist Jean Robert Delcine was assaulted and threatened by police October 12, 2001, because he had been investigating the alleged killing of a 16-year-old by police in Port-au-Prince. Police allegedly killed the boy when they could not find his brother, who they suspected of gang activity. Radio Haiti Inter lodged a complaint against the police inspector who had mis-treated their reporter, but the inspector refused to respond to the summons.

A month later, on November 27, 2001, Radio Kiskeya journalist Evrard Saint-Armand was reportedly arrested after trying to report on an incident in which a young boy was killed in suspicious circumstances in Port-au-Prince. He was taken to the local police station, where police officers reportedly beat him and broke his tape recorder to prevent broadcast of any of the interviews he had conducted.

In the most gruesome attack of the year 2001, Radio Echo 2000 news director Brignol Lindor was hacked to death by a mob including members of a pro-FL organization in Petit Goave. Several days before, according to reports, the assistant mayor for FL had called for "zero tolerance" against Lindor, whom the assistant mayor accused of supporting a rival party. Several of the killers admitted to the attack, and arrest warrants were issued. However, no arrests were affected for more than two months. But even after the arrest of FL-elected official Sedner Sainvilus, a member of the Communal Section Administration, Lindor's family continued to protest the failure to arrest anyone else.

Threatening leaflets were then distributed in mid-February around Petit Goave, warning the family and other journalists to stop drawing attention to the case or risk facing the same fate as Lindor. Between October 2001 and Lindor's death in December, the Federation of Haitian Journalist Associations documented 30 cases of threats or aggression against reporters by supporters of President Aristide. At Lindor's funeral, 24-year-old journalist Francois Johnson told Michelle Faul of the Associated Press he was reconsidering his life's work. "The whole profession is traumatized by Lindor's brutal death," he said at the time. "We are afraid of what is in store for us."

When the national palace was attacked by unknown assailants in December 2001, a rush of targeted reprisal attacks took place against opposition headquarters, radio stations, journalists, and leading opposition figures. Reporters and journalists were victims of harassment and attacks, during which the Haitian police were either not present or did not respond. The Association of Haitian Journalists reported that nearly a dozen journalists left Haiti out of fear of persecution following the attack on the palace.

After the coup attempt, Aristide supporters rampaged through Port-au-Prince and Cap Haitien, the country's second largest city. Private radio stations were targeted, while other journalists were threatened and, in some cases, forced to join the mobs in singing, "Vive Aristide!" according to a report by OneWorld US. At the time, Garry Pierre-Pierre of the New York-based National Coalition for Haitian Rights as well as the publisher of the Haiti Times , called the events a "major setback to the democratic process in Haiti." Mary Lene Smeets, the Latin America director of the Committee to Protect Journalists, said the climate of violence against the press was a tremendous cause for concern. She blamed Aristide for fanning the flames through his statements.

In the early 2000s, some felt that the media is as fragmented as anything else in Haiti, where military coups, government corruption, and political diversion were frequently the norm. In a forum on ethnic media in New York, the Freedom Forum Media Studies Center held a panel discussion on "Haiti's Media: Covering News at Home and Abroad." The discussion centered on media issues related to Haiti, perhaps the Western Hemisphere's poorest country. Participants in the forum disagreed about the problems in the Haitian media. Some observers felt there was no such thing as neutral, fair journalism, even among mainstream media such as the Associated Press and the New York Times . Others felt that the bulk of Haitian media focuses on political coverage (whether fair or not) and not enough time and energy is spent covering essential issues such as ecology, justice, crime and drugs.

Radio Soleil, begun in 1991, broadcasted from Brooklyn, New York as a subcarrier radio station. In the early 2000s it claimed more than 100,000 subscribers and claimed a listening audience of more than 600,000 Haitians spread across New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut. The station broadcasted 24 hours a day, 7 days a week in three languages. Although its owner, Ricot Dupuy, agreed not enough time was spent on central issues like the ecology and crime, he pointed out that he did not have the manpower. "We do not have the means to do in-depth coverage," he said. "Everyone in Haiti is a politician. Everything boils down to politics."

Economic Framework

In 1998, it was estimated that more than 80 percent of the Haitian population lived below the poverty line. That fact, combined with the fact that between 50 and 80 percent of the country's population is illiterate, meant most Haitians got their news from broadcast media and not the print press.

Nearly 70 percent of Haitians depend on agriculture, consisting mostly of small-scale subsistence farming and employing roughly two-thirds of the active workforce. After elections in May 2000 that were widely suspected of irregularities, the international community, including the United States and Europe, suspended almost all aid to Haiti. The result was a destabilization of the currency in Haiti and, combined with fuel price increases, a stark rise in prices in general. By January 2001, however, prices had appeared to level off.

Estimates in 1999 regarding the Gross Domestic Product of Haiti divided sources of revenue three ways: agriculture, 32 percent; industry, 20 percent; and services, 48 percent. The inflation rate, according to 2000 estimates, was 16 percent, and in 1995 the labor force was 3.6 million.

Press Laws

The Haitian Constitution, enacted in 1987 and updated in January 2002, guaranteed all Haitians the right to express their opinions freely on all matters and by any means they chooses (Article 28). It also stated that journalists may freely exercise their profession within the framework of the law, and such exercise may not be subject to any authorization or censorship, except in the case of war.

Journalists may not be compelled to reveal their sources; however, it was their duty to verify the authenticity and accuracy of information. It was also their obligation to respect the ethics of their profession. Article 28-3 of the Haitian Constitution stipulated that all offenses involving the press and abuses of the right of expression should come under the code of criminal law.

Censorship

According to the Haitian Constitution, journalists do not need to reveal their sources, although they are required to verify the authenticity and accuracy of the information they acquire. Part of the obligation includes respecting the ethics of their profession.

As of 2002, more than 200 independent radio stations existed in the country, providing the full spectrum of political views. Unfortunately, self-censorship was fairly pervasive as journalists tried to avoid offending financial sponsors or influential politicians.

State-Press Relations

Two French language daily newspapers frequently criticized the government, but with a 20 percent literacy rate, the majority of the Haitian population did not read these criticisms. Uncensored satellite television was available, but lack of funds prevented it from reaching many people.

Official harassment often happened in the early 2000s in the form of physical abuse by mobs of people. For instance, four journalists were beaten by police at an anti-crime rally in May 2000. A radio director was arrested and charged with defamation and incitement to riot a month earlier.

Regarding state and press relationships, at the beginning of the twenty-first century they are strained and oppositional in purpose. To illustrate, the key suspect in the April 2000 shooting death of Haiti's most influential journalist, Radio Haiti Inter director Jean Dominique, was Lavalas Family Party Senator Danny Toussaint. Try as he may, President Jean-Bertrand Aristide was not impressing free press watchdogs with his efforts to make press freedom a reality in his country. Indeed, Reporters Without Borders in May 2002 put Aristide's name, for the first time, on an annual worldwide list of "predators against press freedom." The Reporters Without Borders list put Aristide in some distinct company: Cuba's Fidel Castro, Iraq's Saddam Hussein and Russia's Vladimir Putin, among more than 30 others.

The Paris-based organization criticized Aristide, saying he obstructed the investigation into Dominique's murder. While the investigation centered on prominent figures within Aristide's ruling Lavalas Family political party, the investigating judge, Claudy Gassant, complained of government interference and intimidation. Gassant's mandate to investigate the case ended in January, and Aristide waited three months to renew it, and did so under pressure on the second anniversary of Dominique's murder in April 2002.

The investigation into Dominique's murder provided a chance for the country to change its image. According to Amnesty International, there was "unprecedented civil mobilization to call for justice for the popular and respected murdered journalist." It cut, Amnesty International stated, across the political spectrum and included human rights organizations, journalists, churches, members of the labor movement and grassroots groups. Amnesty International kept a close eye on the investigation. But Haiti's legal system protected the findings in any investigation. Still Amnesty International pointed out the country had an obligation under both international and domestic law to make sure "full, transparent and impartial" justice was served.

Much of the attitude toward a free press in Haiti can probably be traced to all of the political turmoil in the country. Under dictatorships since 1949, including a period from 1957 through 1986, when Haiti was ruled first by Francois Duvalier, who ruled with brutal efficiency through his secret police, the Tontons Macoutes . In the early 1980s, Haiti became one of the world's first countries to face an AIDS epidemic, and the disease wrought havoc on the nation's tourist industry, which collapsed, causing rising and rampant unemployment. Eventually, unrest festered in the economic crisis.

In the early 2000s Haiti's government remained ineffectual, and the country was a major point for drugs. The country also suffered from an approximately 50 percent unemployment rate, and refugees left eagerly for the United States. Aristide won re-election in 2000, and his government quelled an attempted coup in December 2001, in another event that showed the dangers of being a journalist in Haiti. After the attempt was put down, journalists were forced to seek refuge following a series of attacks by supporters of Aristide. According to the Associated Press, at least one radio station stopped broadcasting in the immediate aftermath of the attempt. Five gunmen were killed, and perhaps as many as 18 others escaped as police retook the palace. Aristide militants attacked reporters outside the National Palace the day of the assault, December 17, 2001. One radio reporter had a pistol placed against his head; others were forced by attackers to praise the president. According to Reporters Without Borders, at least a dozen reporters were assaulted outside the palace, all while police simply stood by and watched. Though no serious injuries were suffered, the reporters were forced by the mobs to leave under threat. Police did nothing, and no arrests were made. At the time, Reporters Without Borders Secretary-General Robert Menard said: "The systematic character of the assaults shows the protesters have received instructions to attack the press."

Aristide himself condemned the attacks on journalists, but given the treatment of reporters in the country, he did not appear to be taken seriously. At one point, he urged his supporters to respect the rights of the press. But later in the same day, Radio Ti-Moun, an educational station run by Aristide's private Foundation for Democracy, charted that the press had "prepared the people psychologically" for the coup. According to the Associated Press report, at least 10 people were killed in the attack on the palace and the accompanying violence. Opposition forces claimed the coup attempt was staged, and one radio reporter said he received threats after he asked a question reflecting skepticism about the coup's authenticity. Several radio stations stopped broadcasting temporarily after the attack, while others played only music. That indicated the climate in which Haitian journalists had to work.

News Agencies

As of 2002, L'Agence Haitienne de Presse (AHP) was Haiti's only local news agency. Founded in 1989, AHP was created to distribute news and information on Haiti and to build stronger ties with both the diaspora and the rest of the world. AHP published daily news releases in both French and English. The AHP also published an annual synopsis of the year's events. It also prepares reports on subjects of common interest, such as elections, the democratic process, and the press. All of Haiti's radio and television stations, foreign and local press, diplomatic missions and international organizations use AHP's services. AHP, according to its own Web site, has grown to a staff of 12 in its main Port-au-Prince office, with another 10 correspondents positioned around the country and one each in the Dominican Republic, Canada and the United States, where there are large Haitian populations.

Broadcast media

In 1997, Haiti had 67 radio stations, 41 AM stations, and 26 FM stations, which reached an estimated 415,000 radios. Two television stations, plus one cable television service, reached approximately 38,000 televisions.

Electronic News Media

As of the early 2000s, Haiti had about 9 telephones per 1,000 citizens. Comparatively, there were 630 telephones per 1,000 users in the United States. Haiti's largest Internet provider, Alpha Communications Network, claimed a 90-percent market share of Internet users. ACN was shut down in September 1999 by the government's telecommunications regulator, the National Communications (Conatel). The shutdown paralyzed the communications ability of Haiti, stopping an estimated 80 percent of Haitian commerce and leaving government offices, embassies, and nearly everyone without Internet access.

Conatel claimed that ACN had sliced into the international business of Haiti's state-run monopoly, Teleco, by selling international phone lines and cards, causing the shutdown of ACN. The charge was later dropped, and the popular ACN was allowed to resume. ACN's popularity is understandable when one considers the average Haitian's annual salary was only US$250 a month, and that, at US$.70 a minute, Teleco's online charge would cost more than an average Haitian's annual income.

Summary

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, journalists in Haiti had good reason to fear for their lives. Although President Aristide said he would do everything in his power to make sure rights were given to the press and the Constitution would be upheld, he had not been willing or able to follow through on that promise. Like Haitians of all ages and walks of life, journalists have at one time or another fled the country. When one of the country's biggest names in journalism can be shot dead in front of his own radio station, and when the government in the best case scenario is slow to investigate and in the worst case scenario actually obstructs the investigation and allows the killer or killers to go free, it does not take much to reach the conclusion that a free press in Haiti was still a long way away.

Significant dates

- 1957: Francois "Papa Doc" Duvalier becomes Haiti's dictator.

- 1971: "Papa Doc" is succeeded by his son, Jean-Claude "Baby Doc" Duvalier.

- 1986: Facing an economic crisis brought on by the collapse of the tourist industry in Haiti caused by a burgeoning AIDS crisis, Jean-Claude "Baby Doc" Duvalier flees the country.

- 1991: Jean-Bertrand Aristide, a Roman Catholic priest, becomes the first elected chief executive. He is deposed in a military coup a few months later.

- 1994: A United Nations Peacekeeping force restores the Aristide government.

- 1996: Rene Preval succeeds Aristide.

- 2000: Aristide is re-elected in elections that were boycotted by the opposition and questioned around the world for their propriety.

- 2000: Jean Dominique, director of Haiti Radio Inter, is gunned down with a guard in front of the station by unknown gunmen. Radio stations and other journalists are pressured to limit their coverage of the attack.

- 2001: Reporter Brignol Lindor is hacked to death by a mob said to include members of a pro-Lavalas Family party group. When friends and family openly protest the lack of progress in the case, leaflets warning them they could suffer a similar fate are passed out in Lindor's hometown of Petit Goave.

Bibliography

Demko, Kerstin. Haitian Media Fragmentation Reflects Haiti's reality. Available from http://www.freedomforum.org .

Faul, Michele. "Journalists in Haiti fear for their lives." Associated Press, 22 Dec. 2001.

Freedom House Press Reports 2000. Available from http://www.freedomhouse.org .

Haiti History, 2002. Available from www.infoplease.com .

Human Rights Watch World Report, 2002. Available from http://www.hrw.org .

"Internet Access in Haiti." Digital Freedom Network, 2000. Available from http://dfn.org .

Lobe, Jim. "Haiti's independent journalists face uncertain future." OneWorld US, 7 Jan. 2001.

United States State Department Report, 2001. Available from www.state.gov .

World Bank Group Reports. Available from http://www.worldbank.com .

Brad Kadrich

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: