Hungary

Basic Data

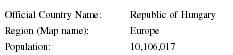

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Hungary |

| Region (Map name): | Europe |

| Population: | 10,106,017 |

| Language(s): | Hungarian |

| Literacy rate: | 99.0% |

| Area: | 93,030 sq km |

| GDP: | 45,633 (US$ millions) |

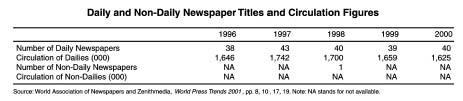

| Number of Daily Newspapers: | 40 |

| Total Circulation: | 1,625,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 194 |

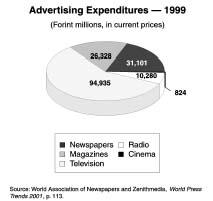

| Total Newspaper Ad Receipts: | 33,781 (Forint millions) |

| As % of All Ad Expenditures: | 14.30 |

| Number of Television Stations: | 35 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 4,420,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 437.4 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 1,576,000 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 157.6 |

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 1,753,000 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 173.5 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 77 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 7,010,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 693.6 |

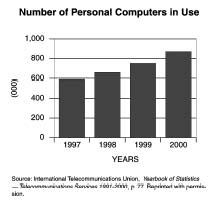

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 870,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 86.1 |

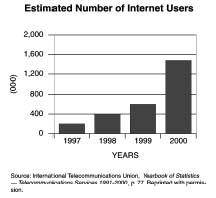

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 1,480,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 146.4 |

Background & General Characteristics

Perhaps the one person that is associated worldwide with excellence in the media, innovation in communications, independent liberalism in journalism and education for the media is Joseph Pulitzer, a man of Hungarian descent. At 17, Pulitzer left Hungary for America where, in a series of newspaper ownerships, he pioneered the use of illustrations and photographs, news stunts and crusades against corruption. As a result of competition with the Hearst Group of newspapers characterized by vicious and lengthy circulation wars, Pulitzer's newspapers became renowned for sensationalism, yellow journalism and banner headlines. His name was later remembered for the foundation of the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism in New York, and endowment of the series of prizes for excellence in journalism, the Pulitzer Prizes.

Thus it is somewhat ironic that nearly 100 years after his death in 1911, the country of his birth is attempting to establish an independent media by means of sensationalism, the rooting out of corruption and mismanagement, and with a political orientation of independent liberalism that was the hallmark of Pulitzer's newspapers in his formative years as a journalist in America.

The need for an independent media results from the period following World War II, during which Hungary was part of the Eastern Bloc and therefore dominated by the Soviet Union. At that time, all media was strictly controlled as an instrument of the Communist Party. In 1989 Hungary became the first country of the Eastern Bloc to move away from the Soviet Union and its attempt to establish an independent media dates from then. The years since independence generally have been successful economically, but the transformation of the media from a state-controlled propaganda machine to an independent and self-policing vehicle of public discourse has been a hard-fought battle. At the turn of the twenty-first century the Freedom House, an independent, non-partisan organization that assess media freedom, awarded Hungary a rating of 27 out of 100, indicating almost complete freedom of the press.

The Nature of the Audience

The population of Hungary is around 10 million, of which 1.8 million (18 percent) live in the capital Budapest. Other major cities are Debrecen (204,000), Miskolc (172,000), Szeged (158,000), Pécs (157,000) and Györ (124,000). Almost two-thirds of the population is urbanized and the remaining one-third has ready access to all media.

Hungary has a highly literate audience. Literacy is estimated at almost 100 percent for men and women, and the level of education is high. Thus it is no surprise that newspapers have a circulation of 194 per 1,000 people, though this is down from the early 1990s when reportedly a phenomenal 400 per 1,000 of the population read newspapers.

The Hungarian language is classified as Finno-Ugrian and is part of the Altaic group of languages. Apart from linguistic relatives in Estonia and Finland, the Hungarian language is unique in Europe, and 95 percent of ethnic Hungarians speak a language very different from other European languages. There exists a possibility the media could marginalize other ethnic groups, but the Hungarian government has made significant commitments both in the constitution and the media to recognize and cater to these groups. The most numerous of the ethnic minorities are the Roma—often called Gypsies—the exact numbers of which are unknown but may be as high as 9 percent of Hungary's population. Germans, Slovaks, Croats, Romanians, Bulgarians, Greeks, Polish, Serbian, Ruthenes and Ukrainians comprise the balance of the population. Of the 13 recognized ethnic minorities in Hungary, it is the status and accommodation of the Roma that is the most serious case for concern and which has received the most attention in the context of minority rights.

Notwithstanding the highly literate nature of the Hungarian population, the fact that the economy is in the process of recovering from the problems inherited from the socialist economic system means the affluence of the average Hungarian remains relatively low in contrast to that of its neighbors to the west. The purchasing power standard in Hungary, estimated by the European Union at 11,700 Euros, is 52 percent of the European Union average. This figure conceals significant hardships that exist in the population, not the least among the unemployed, senior citizens, and the Roma population in general. This climate of hardship and perceived injustice has created a vocal and predominantly liberal journalistic orientation.

Hungary has little in the way of historic traditions of a free media because it was effectively under the influence of the Soviet Bloc since 1945. Any history of media independence present in pre-World War II was lost in the following 45 years of Communist rule. During the Soviet period Hungary's oldest newspaper, Magyar Nemzet , was the principal organ of the party but was in serious decline near the turn of the twenty-first century. With mounting debts and a circulation of only 40,000 it merged with a right-wing daily, Napi Magyarorszag , and in recent years is Hungary's second most popular newspaper. It generally is considered the most right-wing of newspapers, and hence was the most sympathetic to the predominantly conservative governments of post-independence Hungary amid a sea of left-leaning print publications. Foremost among the liberal press are newspapers of the German-owned Axel Springer group, which have a leading position in the Hungarian newspaper market, particularly in the county newspapers outside Budapest.

Most Hungarian journalists cite a great journalistic tradition in their nation, largely a result of the early foundations of journalism during the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In the socialist years since 1945 little movement away from the party line occurred in Hungarian journalism. The only exception was during the time of the Hungarian revolution in November 1956 when many journalists and newspaper editorials supported the head of the independence movement, Imre Nagy. Following the Russian invasion to quell the revolution, a number of journalists were executed and others sentenced to long prison terms. Western observers have given Hungarian journalists a mark of 4 on a scale of 10 for quality of journalism, citing too much commentary, little quality investigative reporting and a tendency to present the newspaper's avowed political leanings with little or no attempt at balance in editorial viewpoint.

The Importance of Newspapers

There are more than 40 daily newspapers in Hungary, and more than 1,600 print publications. The most popular newspaper up to 2000 was Népszabadság with a daily circulation of 210,000. It was surpassed in the beginning of the millennium by a new Swedish-owned, freely distributed tabloid, Metro , which by 2002 had a circulation of 235,000. Newspapers are in a constant circulation war, competing in a declining readership market amid an excess of publications and are increasingly turning to yellow journalism in attempts to gain market share.

Népszabadság Rt. (People's Liberty Co.) was founded in 1990 with 340 million Hungarian forints (HUF) in capital assets. Today it is a powerful business owned by the Swiss-based Ringier Corporation, with some 8 billion HUF annual revenues and it is active in other media fields. Its paper, the Népszabadság (Peoples Liberty) is by far the largest newspaper in circulation in Hungary. Its long-time slogan was "Hungary's Most Popular Daily Newspaper." The paper is of standard size (63 by 47 cm) and is published six times a week (Monday to Saturday). The number of pages varies during the week—Wednesday averages the most (40)—as does the ratio of advertisements—Friday averages the highest percentage (29) of advertisements. It has only a morning edition, similar to all Hungarian newspapers, with the exception of Déli Hírek (News at Noon), a regional newspaper circulated in the Northeast region of Miskolc and the surrounding county of Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén. Déli íírek is on newsstands by noon or the early afternoon, and also has a single edition per day.

The Népszabadság has both permanent features and special supplements over the week. Its standard coverage consists of foreign politics with commentary, home affairs, mirror to the world, mirror to Hungary, culture, forum, market and economy, real estate market, news of the world, sport (in every day's edition), info world, green page, youth/school, the economy and technical/computer electronics. Each weekday there are special sections concentrating on popular subjects. Monday's edition has a regular supplement called "Daily Investor,

In contrast, the second largest newspaper, Magyar Nemzet (Hungarian Nation) has a definite right-wing bias. It is owned by Nemzet Lap és Könyvkiadó (Nemzet Newspaper and Book Publishing Co.) which consists of a number of private shareholders. It calls itself the "bourgeois paper" and acted as a de facto forum. Some would say it also acted as a mouthpiece for the government up to 2002, with an orientation favoring the conservative government in power. Magyar Nemzet has a circulation of about 110,000, is published six times a week from Monday to Saturday, and has permanent columns dedicated to home affairs, foreign affairs/diplomacy, the economy, culture, letters from the readers, a large sports section, and a weekend magazine on Saturday. It usually has two to three pages of advertisements and around 20 to 24 total pages. It is a full-size newspaper.

Magyar Hírlap (Hungarian News), also owned by the Ringier Group, has a circulation of around 38,000, regular (large) size pages and 24 pages on weekdays, but the Saturday edition has 28. Its motto is "The news is intangible, the opinion is free," thus claiming that it is the most objective of all Hungarian newspapers. Its regular columns are the topic of the day, foreign affairs, home affairs centered on Budapest, culture, letters from the readers, world news, the domestic economy, the world economy, E-world, food market, science, sports and a weekend magazine called "As You Like It" in the Saturday edition.

Népszava (People's Word) a left-wing broadsheet owned and influenced by trade union interests, has about the same circulation as Magyar Hírlap . Its regular columns include home affairs, foreign affairs, background, opinion, world, culture, television programming, letters from readers, sports and world news.

There are two economic papers published five times a week on weekdays. In the mid-1990s they were one paper, then they split into Napi Gazdaság (Daily Econo my) and Világgazdaság (World Economy). They are much more expensive than the dailies, especially Világgazdaság , which costs 190 HUF, and Napi Gazdaság 's cost of 178 HUF. In comparison Népszabadság sells for 85 HUF, Magyar Nemzet 98 HUF, Magyar Hírlap 99 HUF and Népszava 89 HUF.

In Budapest there is an English-language weekly, the Budapest Sun , which primarily covers topics of concern to the business community. Other European-language newspapers are readily available and often with same-day coverage as the rest of Europe. North American newspapers ( USA Today, New York Times ) usually are editions from two to three days earlier. There is no restriction on their import.

A major feature of Hungarian newspaper readership is the numbers, circulation and impact of 18 regional newspapers outside Budapest. Hungarian county newspapers and magazines are noteworthy for their dominance by the Axel Springer German newspaper conglomerate. Axel Springer is the publisher of nine county papers, or almost half of all the county papers, as there are 19 counties in Hungary. Pest County, where Budapest is located, has no newspaper of its own but owing to the dominance of Budapest in Hungarian affairs, the national dailies devote much of their news coverage to what is happening in the capital. Only three counties— Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén, Heves and Fejér—have more than one paper. Total circulation of the nine county papers is about 250,000 with an average circulation around 37,500, thus giving them as important an impact, if not more, than the so-called national dailies. Axel Springer's county newspapers are the following: Békés Megyei Hírlap (Békés County News, circulation of 33,200); Új Dunántúli Napló (New Transdanubian Diary, 55,000); Jászkun Krónika/Új Néplap (Jászkun Chronicle/New People's Paper, 16,000); Heves Megyei Hírlap (Heves County News, 21,000); Nógrád Megyei Hírlap (Nógrád County News, 17,000); Somogyi Hírlap (Somogy News, 25,365); Petöfí Népe (Petöfí's People, 50,485); Tolnai Népújság (Tolna People's Paper, 23,650) and 24 Óra (Twenty-four Hours, 25,365).

The remaining county newspapers are owned either by another German-based group, Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitungsgruppe (WAZ), an Austrian-based conglomerate, Inform Stúdió Ltd. or the British-based Daily Mail group.

The second largest conglomerate, Pannon Lapok Társasága (Society of Pannon Papers), a division of Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitungsgruppe (WAZ), is one of the largest European regional media concerns, consisting of more than 160 companies and an annual turnover in excess of 4 billion Deutsche Marks in 2001. It has papers in Germany, Austria, Hungary and Bulgaria. In Hungary it has four county papers with a total circulation of around 250,000. These papers have a radio and television program color attachment called RTV-Tipp. The newspapers are: Zala Megyei Hírlap (Zala County News, with a circulation of about 65,000); Napló (Diary, 56,400); Vas Népe (Vas People, 64,200) and Fejér Megyei Hírlap/Dunaújvárosi Hírlap (Fejér County News/Dunaújváros News, 53,500 and 9,800, respectively).

The third county newspaper group in Hungary is Funk Verlag—Inform Stúdió. The publisher has Austrian majority ownership (Inform Stúdió Ltd.) but with its Hungarian center in Miskolc. It publishes three county newspapers with a total circulation exceeding 136,000. Its papers are: Hajdú-Bihari Napló (Hajdú-Bihar Diary, 50,400), Észak-Magyarország (North Hungary, 37,350), and Kelet-Magyarország (East Hungary, 48,750).

Finally the Rothermere family, based in Britain and publishers of the Daily Mail in the UK, publishes two county papers in Hungary with a total circulation of more than 150,000. The Kisalföld (Small Hungarian Plain) is the leading county paper in Hungary, with regional editions distributed across county borders. Its other paper is Délmagyarország/Délvilág (South Hungary/Southern Part).

Additionally, there are three minor county/urban county seat dailies. They are: Békés Megyei Nap (Békés County Daily, 10,680), Komárom-Esztergom Megyei (Komárom-Esztergom County News, 15,000) and the only afternoon-edition newspaper, Déli Hírek (News at Noon, 18,000).

In the magazine market, a company called AS-Budapest publishes most of the major magazines such as the popular women's magazines Kiskegyed (My Fine Lady), Csók és Könny (Kisses and Tears), Kiskegyed konyhája (Kitchen of the Kiskegyed), Gyöngy (Pearl), TVR-hét (Weekly Television and Radio Programs), Lakáskultúra (Homes Culture), and Party . AS-Budapest also publishes a Sunday paper called Vasárnap Reggel (Sunday Morning).

In twenty-first century Hungary there are few logistical problems with producing such a large output of print media. Most presses are modern offset presses, usually manufactured and imported from within Europe. News-print is readily available in adequate quantities. In a country that had a socialist history of trade union membership, there have been no strikes or work stoppages that have significantly affected newspaper production. The average print journalist's salary in Hungary in 2002 was around HUF 170,000 a month. Junior staff earn around HUF 120-150,000, more experiencedjournalists (staff members) around HUF 200-250,000, editors between HUF 250-400,000, senior editors up to 500,000, and editor-in-chiefs' salaries may go up to 1 million HUF. Television journalists are said to earn considerably more. Internet journalists earn less than the average, around 20-40 percent less than their newspaper colleagues.

Freelance journalists do not exist in Hungary in the Western sense of the term. That is, newspapers do not, or cannot, afford to pay a separate story the sum it would be worth and that helps explain why there is so little independent investigative journalism. There are journalists who do not have a single workplace and sell pieces to different publications, but their articles are public relations pieces. It is suspected that Playboy and similar magazines pay the largest sums for a piece, around HUF 10,000 (U.S. $39.50) per flekk , a Hungarian journalistic term for the length of the text, around 1,500 characters with spaces.

There also exists a strange phenomenon in Hungary because according to tax authorities, there are only a couple of journalists in the whole nation! This means that few of them are registered as being employed as a journalist in their medium, and even those who are official journalists receive only the minimum wage of HUF 50,000 per month. The remainder of their salary is paid according to an agreement with the small companies of the journalists. This way the employer can avoid paying Social Security and other taxes.

In a country the size of Hungary, the depth and extent of newspaper coverage can be viewed as remarkable. The Observer Budapest Media Watch Co. regularly examines 162 newspapers and periodicals in Hungary, although most have circulations of about 5,000 to 10,000 subscribers. The generally adverse economic climate is the major factor in the low percentage of advertising, with the result that subscriptions, circulation, market area and discretionary retail sales become major influences on newspaper viability. On the other hand, advertisers have very little influence on editorial policies. As the economy strengthens and full European Union integration brings more foreign investment, the importance of advertising to the newspaper industry can be expected to increase.

As a result of the almost homogeneous Hungarian population, most publications are printed in Hungarian. Major minority newspapers in Hungary and their ethnic audience are: Amaro Drom (Roma), Ararát (Hungarian and Armenian), Barátság—Prietenie (Hungarian and Romanian), Foaia Romaneasca (Romanian), Haemus (Bolgár), Hromada (Hungarian and Ukrainian), Hrvatski Glasnik (Croatian), Közös Út—Kethano Drom (Hungarian and Roma), Lungo Drom (Roma), Ludové Noviny (Slovakian), Neue Zeitung (German), Porabje (Slovenain) and Srpske Narodne Novine (Serbian).

The news media in Hungary is generally seen as having a left-wing bias, an accusation that the ruling political parties in the 1990s disliked and have attempted to counterbalance by political appointments in oversight bodies. This accusation is most prevalent in Budapest which, by nature of its population and political importance, is most affected by the political climate in Hungary. In smaller cities and towns, local news is just as important and the circumstances of individuals become more important than the political agenda. In some newspapers there have been instances of anti-Semitism that have found voice in the media, but the government moved quickly to silence such right-wing extremists.

Economic Framework

In the 10 years since the fall of the Soviet Union, the economy of Hungary has been one of the most successful in making the transition to a privatized, market economy. As Hungary entered the new millennium, inflation was at a manageable 9 percent, growth was at a robust 3.5-4 percent and productivity was among the highest of all Eastern European nations. Based on this successful economic transformation, Hungary was one of the first former communist nations to gain candidate status for entry into the European Union. Economically, the European Union has stressed that the Hungarian government needs to further reduce inflation, cut the budget deficit and reform the tax code.

The European Union also attaches considerable importance to the status of the press, with particular emphasis on freedom and independence. In addition, the European Union has used the question of the status of the Roma as a barometer upon which to judge Hungary's suitability to join the Union. In this regard the media has served in part as a barometer with which to judge Hungary's movement toward recognition and accommodation of its ethnic minorities, particularly the Roma. Some sections of the press have acted as watchdogs toward government mismanagement and discrimination, and acted to publicize and criticize racist acts directed against the Roma.

More than 80 percent of the print media and more than 70 percent of the broadcast media (in total, 30 radio stations and 29 television stations) are in private hands. The process started almost immediately after independence with the purchase of the existing media. Since independence there has been a veritable explosion of independent newspapers and magazines. Recently the print media has become highly competitive and of high quality. There is no direct control of the electronic media by the government, although there have been accusations that the government seeks to influence the media in its structuring and appointments to the Boards of Trustees.

Press Laws

The Constitution of the Hungarian Republic, written in 1949 but greatly amended upon independence in 1989, guarantees freedom of speech and freedom of the press under Act XX, Article 61, which states (paraphrased):

- Part One: In the Republic of Hungary everybody has the right to freely express their opinion and have access to and disseminate data concerning the public.

- Part Two: The Republic of Hungary acknowledges and protects the freedom of the press.

- Part Three: The amendment of the Act on the publication of data of public concern and on the freedom of the press requires a two-thirds majority of Parliament.

- Part Four: A two-thirds majority is needed for the appointment of the leaders of public radio, television and news agencies, the licensing of commercial radio and television stations and the passing of any act on the prevention of media monopolies.

These freedoms are generally respected. The most important subsequent legal qualifications were in 1994 when the Constitutional Court ruled that Article 232 of the criminal code was unconstitutional, thus removing the crime of libel from the criminal code and affirming the right of citizens/journalists to criticize public officials. In effect it meant that journalist harassment by means of libel lawsuits was no longer possible. This provision was never completely accepted by the government, and a 2000 law would permit journalists to be tried in criminal court if the journalist in question was continually charged with libel. This law has aroused much protest internally and by external media watchdogs. In 1996 a second landmark law affecting the media was passed. It was aimed specifically at the creation of commercial broadcast media and making the state public broadcasting system a separate public broadcasting service at more distance from the government. To date, the former has generally been successful while the latter has been only partially realized and is the cause of much discontent.

Finally, in 2000 the Constitutional Court removed another section of the criminal code forbidding "deliberately spreading panic" that in the past had been used against journalists.

It is worth noting that the Media Act (Act No. 1 of 1996 on Radio and Television services and passed by an 89 percent parliamentary majority in 1996) is one of the most problematic acts in Hungary. Reformation of this act has been on the political agenda many times since its passage with limited success. For example, Hungary is the only associate country of the European Union that has not closed negotiations with the European Union on the so-called "audiovisual chapter." As a consequence, the Hungarian film industry lost access to large amounts of European Union subsidy money, as it was not eligible for support. Both the former government and the former opposition (who in 2002 reversed their positions in government) blame it on the other side. The former government (now opposition) says that the then opposition (now government) consistently voted against amendments to the media law making it impossible to close the negotiations. The opposition said that it had no real influence on the amendment as the members of the Board of Trustees consisted only of the leading government party, and that is why it voted against the amendments.

In 2002 the Board of Trustees was constituted with members from both sides. Thus the prognosis is more positive for the Media Act to be amended and harmonized with European Union requirements. The issue was raised in parliament again in the summer of 2002 for the fourth time in as many years. Principal changes will be the re-regulation of broadcasting and urban county seat requirements, the introduction of the concept of "European program," the preference for programs made in Europe, stricter measures protecting youth (less violence on the screen) and the amendment of advertising rules.

There are laws codifying the privacy of individuals and these are generally respected. In Hungary the judiciary is independent under the constitution and a National Judicial Council nominates judicial appointments—other than the Supreme Court or the Constitutional court whose members are elected by parliament—at the local and county level. The Constitutional Court decides on all matters of legal interpretation and has been required to make decisions a number of times on matters affecting the media. All decisions emanating from this court have been seen as impartial and fair.

Censorship

There is no government body that monitors the press, either via pre-publication censorship or modes of compliance. However in view of the general adversarial relationship between the media and the government, the International Journalists Network (IJNET) claims that information from government officials is not readily forthcoming. This is despite an existing Freedom of Information Act that provides for press access to government activities. As a result, the IJNET suggests that the media has had "modest success" in uncovering alleged government wrongdoing, malfeasance or illicit activities. In 1998 the government passed a law limiting information that could be revealed about official meetings, banning recordings or transcripts, and limiting information to the proposed agenda and meeting attendees.

Overall the subject of censorship is a delicate issue. For example, although there is no "official" censorship in Hungary, many impartial observers have noted the blatant manner in which administrations since independence (ruling from 1998 to 2002) have tried to influence the media. The most egregious example seems to have occurred during the general elections in Hungary in May 2002. The fourth general election since independence in 1989, this generally was agreed to be the most virulent campaign ever waged, with accusations of lying and hatred from both sides. In particular, public opinion polls were published in the government newspapers predicting a clear government majority and saying that FIDESZ (Fiatal Demokraták Szövetsége or Federation of Young Democrats), the incumbent party, would win again. But exactly the opposite happened. After the first round of elections, the MSZP (Magyar Szocialista Párt or Hungarian Socialist Party) had a slight advantage of only 1 percent. However, its ally, the Alliance of Free Democrats had a better position than the MIÉP (Magyar Igazság és Élet Pártja or Party of Hungarian Justice and Life), the only potential partner of the government. MIÉP is considered as an extremist right-wing party and it they had made a coalition with FIDESZ, Hungary probably would have reduced chances for European Union accession.

Between the two election rounds, then Prime Minister Viktor Orbán delivered a 40-minute speech filled with hatred, scaremongering and raising populist topics such as fear of the Communists returning, possible loss of homes and children, and religion being threatened and in danger of abolition. State television broadcast the speech in its entirety, and then rebroadcast it free of charge, not as a political advertisement (in which case it would have cost FIDESZ a fortune) but as a program of public interest.

Two days before the second round of the elections, a program defaming the MSZP candidate for prime minister was broadcast at peak evening viewing time, and on every program between the elections one could see only Orbán opening factories, talking to the people, shaking hands, crowds supporting him and so on, whereas there was hardly any news about the opposition parties campaign.

Despite this, Orbán and his FIDESZ party did not come out on top, and in 2002 Hungary elected a new government. One of the first priorities of the new government was to restructure the Board of Trustees, which governs the broadcast media. The recent board has representatives from both the government and the opposition. It is too early to judge the relationship between the new government and the media, but there is hope that it will try to exert less influence than the former government. It might also be assumed that given the left-wing bias in much of the Hungarian media, apart from Magyar Nemzet and a few periodicals, the media will be probably be more tolerant of the mistakes and faults of the new government.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

The Hungarian government has sometimes had a rocky relationship with the foreign media. While there are no restrictions on foreign journalists, no accreditation required and no violence against foreign media, the government is suspicious of the role foreign media plays, probably because of a perceived influence of foreign media on the process of European Union accession. In particular, the government in the past has accused foreign media of "spreading lies about Hungary abroad," and in 2000 then Prime Minister Viktor Orbán took the unusual step of naming three foreign newspapers that he claimed were trying to discredit Hungary: the New York Times, Die Zeit and Le Monde , all amongst the most reputable newspapers in the world. Having said that, some commentators noted that the three are liberal in their orientation and hence their pronouncements were bound to rankle the conservative governments of that time.

As much of an irritant as foreign media are in Hungary, the oversight provided by other media watchers has proven to be effective—and mostly critical. The British Helsinki Human Rights Group, the Our Society Enlightenment Centre and domestic organizations such as the Openness Club have kept a constant commentary on press issues and freedoms in Hungary and are generally effective.

News Agencies

The official Hungarian news agency is MTI Co. (Magyar Távirati Iroda or Hungarian Telegraph Office). Founded in March 1881, then the news, reports and photographs of the MTI Co. since then have been the backbone of information released in the Hungarian press. The company has a staff of 400, including 19 county reporters and 14 reporters abroad, plus a number of photo reporters and journalists on 24-hour shifts, processing more than 10,000 pages of printed information daily. The fact that MTI produces some 700 news items per day shows how prolific it is in a country of only 10 million. As a result, there is extensive coverage of most issues in Hungary and those who use it generally see MTI Co. as fair and balanced. Almost all foreign news agencies are represented in Hungary, including Associated Press, Reuters, Inter-fax, Bloomberg and Dow Jones, as well as a number of European and Austrian newspapers that have offices in Budapest. The UK's Guardian and the Independent newspaper groups also have offices in Hungary.

In order to represent the Roma population more extensively and perhaps fairly, the Roma have their own news agency, the Roma Press center. In addition, Roma media television (Patrin TV News Magazine) and radio ("Roma 30 minutes") as well as Roma Print Media (Lungo Drom, Amaro Drom, Rom Som) have offices in the larger communities outside Budapest that distribute Roma news.

Broadcast Media

Television broadcasts are in Hungarian. However, there is minority language print media, and state-run radio broadcasts two-hour programs daily in Romany, Slovak, Romanian, German, Croatian and Serbian. State-run television also carries a 30-minute program for every major minority group. This programming is written and produced by the minority groups. Moreover, those minority groups without daily programming have weekly or monthly programs in their language. These programs may be repeated during off-hours on weekends. In February 2001 the radio station Radio C, took to the national airwaves with a seven-year license to broadcast in Romany for the Roma population.

The broadcast media has been the one area of concern in the transition to a free press. In 1989 the government controlled all electronic media, but plans for dismantling this system were put in place early in the life of an independent Hungary. Early difficulties in the privatization and regulatory agencies were solved by the media law of 1996 that was one of the most influential instruments of change for media in the former Soviet Bloc. At the turn of the twenty-first century only three electronic media outlets were government owned: Radio Hungary, Hungarian Television and Duna TV. Moreover, it was estimated that state television was watched by less than 10 percent of the viewing audience in the year 2000.

Notwithstanding this low market share, Hungarian television has been the focus of much of the discussion over the provision of a free press and the removal of government control and influence. Specifically, the state broadcast media have laid off a large number of journalists and administrative personnel, citing massive financial losses. This is almost certainly true but the government has been accused of selective layoffs, in particular firing journalists unsympathetic to the government. Moreover the Board of Trustees that governs executive positions, and ultimately programming, was weighted towards persons favoring the coalition government. Indeed, the board was incomplete with opposition seats remaining unfilled while they apparently fought amongst themselves for representation.

This infighting caused diplomats overseeing Hungary's accession into the European Union to strongly urge that this element of media affairs be resolved as it would hurt accession chances, a reprimand that is unusual and therefore indicative of a serious problem. Recently, Parliament and the Constitutional Court were embroiled in this dispute.

An example of the kind of interference in program content that has characterized Hungarian television and that has irked many Hungarians is a situation where one of Hungary's leading commercial televisions, RTL Klub, had a very popular weekly program called "Heti Hetes" (Weekly Seven), a talk show in which renowned Hungarian guest personalities (actors, writers, comedians) commented on the news of the week. It was among the two or three most popular and most watched shows on commercial television. Originally it was broadcast live, then after a few months it was filmed in a studio on Thursday night and broadcast Saturday night, starting quite late (about 10 p.m.). The program had a strong anti-government attitude but made fun of any politician, irrespective

Another example of government influence on the media was the case of the Hungarian writer, Péter Kende. He wrote a book called A Viktor about the former prime minister in which he exposed several negative characteristics of the former official. There was no formal government protest against the book nor was the writer sued, but the tax authority invaded his office the day after the book's release (the Hungarian tax authority has a history of use by the government to investigate and punish citizens) and a popular television program broadcast on state television in which Kende had an interest was taken off the air. Additionally, in many bookstores a few people were discovered wanting to buy all the books available, probably in an attempt to eliminate them from the market.

The potential for government interference in information dissemination is further exacerbated because Radio Hungary is the only radio station to cover the entire country and hence provides the opportunity for government to reach areas that television, through its limited appeal, does not. Radio Hungary also has come under much criticism as a government mouthpiece. In contrast, commercial radio stations have a limited local reach and provide little news.

Notwithstanding these problems with a state media that controls only 10 percent of the total viewing market, private electronic media flourish to the extent that Western private consortia have opened up television channels in Hungary. However, in 2000 during a sale of local radio stations to further privatize the media, buyers with ties to Hungary's right were favored by the licensing body over bidders such as the BBC, Radio France and Germany's Deutsche Welle—an occurence leading some to comment that Hungary was not as committed to a free international press as it has claimed.

Electronic News Media

There are a large number of electronic news media sites that may be accessed by the 20 percent of Hungarian households connected to the Internet. Of significance, eMarketer believes that academic users make up more than half of the estimated Internet users, suggesting that among educated Hungarians, Internet news access may be an important trend. This is reinforced when one considers that the average Hungarian Internet user is usually between 20 and 25 years of age. Moreover, for those without Internet access, the market economy has created a large number of Internet cafes that provide access to the Internet for those who are not online at home. The major areas without Internet access are more rural, and often are areas of greater poverty. News flow is both voluminous and freely available both domestically and from international sources.

Hungary's online magazines total around 440, with some of the more popular subjects being technical and natural sciences, culture and arts, local and municipal issues, politics and public life, portals, and health and lifestyle. Overall, there is a wide variety of online magazines covering many areas of interest.

Education & TRAINING

Since 1989 there has been dramatic growth in both the number of journalists graduating from higher education establishments and a large number of private institutions led by well-known journalists (for instance: Komlósi Stúdió) or founded by papers (Népszabadság Stúdió) that teach journalists. The problem is that most instructors teaching journalism in the institutions were trained during the socialist period and hence have little appreciation of the need and application of a free press and all that it entails. Thus graduating students are technically good, but lack an ability to discriminate in selection of media content or provide balance in their coverage. Moreover, they feel obliged to insert their own commentary (by liberal use of adjectives and long-winded impressions) while burying the facts.

The most prestigious journalist schools are in the communications departments in Budapest's Eötvös Lo-rand University and Szeged University (the latter also has a presence in Budapest). Smaller universities in the countryside have similar departments. In reality, working journalists indicate journalism schools have only one function and that is to assist students with the opportunity to practice journalism in a working editorial office for some months, and if they are good, they may have a job opportunity. Moreover, they add that with the knowledge of two Western languages a graduate of any discipline has a good chance to become a journalist regardless of writing ability.

Once employed, journalists have the benefit of ongoing training through a number of bilateral programs that bring in teachers from the BBC, major U.S. newspapers and the German media. The Independent Journalism Center in Budapest has been at the forefront of this training program, funded in the early days by the U.S. financier George Soros, who put significant financial resources into media development in his native Hungary.

Summary

The transformation of Hungary's media from a state-controlled, politically dominated institution in past years to a twenty-first-century competitive, uncensored market with the majority of print and electronic media in private hands—all in the space of 10 years—is a remarkable transformation. Moreover, the quality of journalism and programming is high. The only apparent impediment to a nearly flawless media role is the lingering tendency of government to see the press as an adversary, and thus try to mute its criticism. This situation is most apparent in the electronic media, and particularly in the regulation of state television companies. The regulating board has remained heavily politicized but the demand for change is strong, as shown in March 2001 when around 6,000 demonstrators marched in Budapest to demand an independent advisory board. The change of government in 2002 created the climate for such a change, and change must occur in order to facilitate Hungary's accession into the European Union.

Significant Dates

- 1989: Amendment to the Constitution of the Hungarian Republic, written in 1949, guarantees freedom of speech and freedom of the press under Act XX, Article 61.

- 1994: The Constitutional Court rules that Article 232 of the criminal code was unconstitutional, thus removing the crime of libel from the criminal code and affirming the right of citizens and journalists to criticize public officials.

- 1996: Passage of The Media Act (Act No. 1 of 1996 on Radio and Television services).

- March 2001: Around 6,000 demonstrators march in Budapest to demand an independent advisory board for state electronic broadcasting.

Bibliography

Bajomi-Lázár, Péter. Media Policy Proposals for Hungary . The Center for Policy Studies, Open Society Institute. Available from http://www.osi.hu/ipf/pubs.html .

Country Ratings . Freedom House Media, 1999. Available from http://freedomhouse.org/pfs99/reports.html .

"Europa-Enlargement relations with Hungary." The European Commission. Available from http://europa.eu.int/comm/enlargement/hungary/index.htm .

"Hungary 2001: The Hungarian Media Today." British Helsinki Human Rights Group. Available from http://www.bhhrg.org .

"Hungary." In World Press Freedom Review 2001 . Available from http://freemedia.at/wpfr/hungary.htm .

"Hungary." U.S. Department of State Country Reports on Human Rights Practices . U.S. Department of State, 2001. Available from http://www.state.gov .

"Hungary Press Overview." International Journalists Network. Available from http://www.ijnet.org/profile/CEENIS/Hungary/media.html .

Richard W. Benfield

Dr. Zoltán Raffay