Ireland

Basic Data

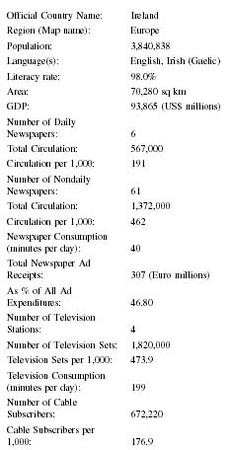

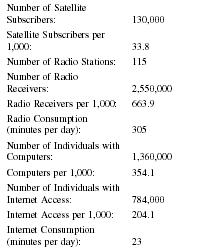

| Official Country Name: | Ireland |

| Region (Map name): | Europe |

| Population: | 3,840,838 |

| Language(s): | English, Irish (Gaelic) |

| Literacy rate: | 98.0% |

| Area: | 70,280 sq km |

| GDP: | 93,865 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Daily Newspapers: | 6 |

| Total Circulation: | 567,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 191 |

| Number of Nondaily Newspapers: | 61 |

| Total Circulation: | 1,372,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 462 |

| Newspaper Consumption (minutes per day): | 40 |

| Total Newspaper Ad Receipts: | 307 (Euro millions) |

| As % of All Ad Expenditures: | 46.80 |

| Number of Television Stations: | 4 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 1,820,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 473.9 |

| Television Consumption (minutes per day): | 199 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 672,220 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 176.9 |

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 130,000 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 33.8 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 115 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 2,550,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 663.9 |

| Radio Consumption (minutes per day): | 305 |

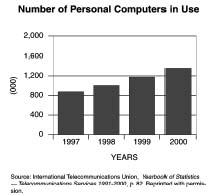

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 1,360,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 354.1 |

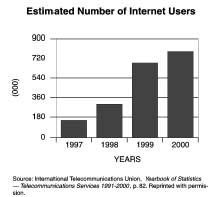

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 784,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 204.1 |

| Internet Consumption (minutes per day): | 23 |

Background & General Characteristics

The Republic of Ireland, which occupies 5/6 of the island of Ireland, is roughly equal to the state of South Caxsrolina in terms of size and population. Half the population is urban, with a third living in metropolitan Dublin. Ireland is 92 percent Roman Catholic and has a 98 percent literacy rate. Despite centuries of English rule that sought to obliterate Ireland's Celtic language, one-fifth of the population can speak Gaelic today. Full political independence from Great Britain came in 1948 when the Republic of Ireland was established, but the United Kingdom maintains a strong economic presence in Ireland.

The printing press came to Ireland in 1550. Early news sheets appeared a century later. The Irish Intelligencer began publication in 1662 as the first commercial newspaper, and the country's first penny newspaper, the Irish Times, began in 1859. The Limerick Chronicle , which was founded in 1766, is the second-oldest English-language newspaper still in existence (the oldest is the Belfast Newsletter ).

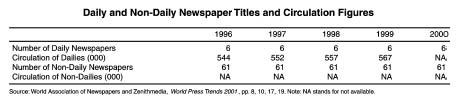

Irish newspapers are typically divided into two categories: the national press, most of which is based in Dublin, and the regional press, which is dispersed throughout the country. The national press consists of four dailies, two evening newspapers, and five Sunday newspapers. There are approximately 60 regional newspapers, most of which are published on a weekly basis. Competition among newspapers in Dublin is spirited, but few other cities in Ireland have competing local newspapers.

Roughly 460,000 national newspapers are sold in the Republic each day. The sales leader is the Irish Independent, a broadsheet especially popular among rural, conservative readers. The second best seller is the Irish Times , which is regularly read by highly educated urban professionals and managers. The Irish Times is probably Ireland's most influential paper. The third most popular national daily in Ireland is the tabloid The Star , an Irish edition of the British Daily Star . The Irish Examiner sells the least nationally, but it is the sales leader in Munster, Ireland's southwest quarter. Published in the city of Cork, the Irish Examiner is the only national daily issued outside of Dublin.

Some 130,000 evening newspapers are sold every day in Ireland. The leader is the Evening Herald , a tabloid popular in Dublin and along the east coast. The other evening paper is the Evening Echo , a tabloid published in Cork, and like its morning sister paper the Irish Examiner, popular in Munster.

Five Sunday newspapers are published in Ireland, with a total circulation of 800,000. The Sunday Independent, like the daily Irish Independent , has the largest circulation. Sunday World , a tabloid, comes in a close second. The other broadsheet, the Sunday Tribune , has a circulation of less than a third of Sunday Independent's . The fourth most popular Sunday paper is the Sunday Business Post , read by highly educated professionals and managers. The lowest circulating Sunday paper is the tabloid Ireland on Sunday , which is popular among young adult urban males. The other weekly national newspaper in Ireland is the tabloid Irish Farmer's Journal , which serves Ireland's agricultural sector.

Newspaper penetration in Ireland is about the same as that of the United States: 59 percent of adults read a daily paper. The newspapers that are most-often read are Irish. Of the 59 percent of adults who read daily newspapers, 50 percent read an Irish title only, 5 percent read both Irish and UK dailies, and 4 percent read UK titles only. Newspaper reading patterns change on Sunday, when 76 percent of adults read a paper. Of this 76 percent, 51 percent read an Irish title only, 16 percent read both Irish and UK Sundays, and 9 percent read UK titles only. The total readership of UK Sunday newspapers is 25 percent, compared with 9 percent who read UK daily papers.

Regional newspapers have a small readership, but one that is loyal, a fact that has turned regional papers into attractive properties for larger companies to buy. Examiner Publications, for example, has bought nine regional papers: Carlow Nationalist, Down Democrat, Kildare Nationalist, The Kingdom, Laois Nationalist, Newry Democrat, Sligo Weekender, Waterford News & Star , and Western People . Other major buyers of regional

Unlike their national counterparts, regional newspapers carry little national news and have traditionally been reluctant to advocate political positions. This pattern did not hold during the 2002 abortion referendum, however. The Longford Leader was reserved, complaining that various organizations had pressured "people to vote, on what is essentially a moral issue, in accordance with what they tell us instead of in accordance with our own consciences." The Limerick Leader , by contrast, urged its readers to vote for the referendum: "Essentially the current proposal protects the baby and the mother. Defeat would open up the possibility of increased dangers to both."

There are 30 magazine publishers in Ireland publishing 156 consumer magazines and 7 trade magazines. Only five percent of magazines are sold through subscription in Ireland; most are sold at the retail counter. One-fourth of magazine revenues come from advertising; the remaining three-fourths comes from sales. By far the most popular magazine in Ireland is the weekly radio and television guide, RTÉ Guide , which far outsells the most popular titles for women ( VIP and VIP Style ), general interest ( Buy & Sell and Magill ), and sports ( Breaking Ball and Gaelic Sport ).

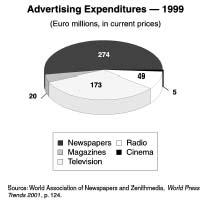

Like Ireland's newspapers, Ireland's indigenous magazine publishers face strong competition from UK titles. According to the Periodical Publishers Association of Ireland, four out of every ten magazines bought in Ireland are imported. Magazines suffered a financial blow in 2000 when the government banned tobacco advertising, which had been the second-largest source of magazine advertising revenue. Magazines receive a very small share of Ireland's advertising expenditure: in 2000, magazines received only 2 percent; newspapers received 55 percent; and radio and television received 33 percent.

A recent survey of 46 Irish book publishers found a vital book publishing industry. Seventy percent of book publishing in Ireland is for primary, secondary, and post-secondary education. Most of the remaining 30 percent is non-fiction, but the market for Irish fiction and children's books is active. Irish book publishers sell most of their books domestically (89 percent), although export sales (11 percent) are notable. More than 800 new titles are published each year, and Irish publishers keep about 7,400 titles in print.

Economic Framework

During the 1990s, Ireland earned the nickname "Celtic tiger" because of its robust economic growth. No longer an agricultural economy in the bottom quarter of the European Union, Ireland rose to the top quarter through industry, which accounts for 38 percent of its GDP, 80 percent of its exports, and 28 percent of its labor force. Ireland became a country with significant immigration. The economic boom, which included a 50 percent jump in disposable income, also led to increased spending in the media as well as increased numbers of media operators in Ireland. The underside of these achievements is child poverty, real estate inflation, and traffic congestion.

By far, the largest Irish media company is Independent News and Media PLC, which sells 80 percent of the Irish newspapers sold in Ireland. Independent News publishes the Irish Independent , the national daily with the highest circulation in Ireland, the two leading national Sunday newspapers, the national Evening Herald , 11 regional newspapers, and the Irish edition of the British Daily Star . Yet these properties, along with a yellow page directory, contribute only 28 percent of the revenues of Independent News; most of the rest comes from its international media properties. Despite the dominance of Independent News in Ireland, the Irish Competition Authority has concluded that the Irish newspaper industry remains editorially diverse.

The mind behind Independent News is Tony O'Reilly, whose 30 percent stake in the company is worth $430 million. O'Reilly founded Independent News in 1973 with a $2.4 million investment in the Irish Independent. Now the company includes the largest chains in South Africa and New Zealand, regional papers in Australia,

There is some media cross-ownership in Ireland. A few local newspapers own shares in local commercial radio stations. Independent News has a 50 percent financial interest in Chorus, the second largest cable operator in Ireland. Scottish Radio Holdings owns the national commercial radio service Today FM as well as six regional newspapers. O'Reilly is the Chairman not only of Independent News, but also of the Valentia consortium, which owns Eircom, operator of one of the largest online services in Ireland, eircom.net .

Most Irish journalists, both in print and in broadcast, belong to the National Union of Journalists, which serves as both a trade union and a professional organization. The NUJ is the world's largest union of journalists, with over 25,000 members in England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland. Recently, the NUJ fought a newspaper publishers' proposal to give copyright of staff-generated material to media companies to stop them from being able to syndicate material without paying royalties to journalists.

Ireland's largest publishers are represented by National Newspapers of Ireland (NNI). Originally formed to promote newspaper advertising, it has expanded to lobby the government on major concerns of the newspaper industry.

Press Laws

Although the Irish Constitution does not mention privacy per se, the Supreme Court has said, "The right to privacy is one of the fundamental personal rights of the citizen which flow from the Christian and democratic nature of the State." Legislative measures to protect privacy include the Data Protection Act of 1988, which regulates the collection, use, storage, and disclosure of personal information that is processed electronically. Individuals have a right to read and correct information that is held about them. Wiretapping and electronic surveil-lance are regulated under the Interception of Postal Packets and Telecommunications Messages (Regulation) Act, which was passed after the Supreme Court ruled in 1987 that the unwarranted wiretaps of two reporters violated the constitution.

Because there is no press council or ombudsman for the press in Ireland, the main way to deal with complaints about the Irish media is to go to court. Irish libel laws leave the media vulnerable to defamation lawsuits, which are common. Libel suits are hard to defend against, so the press often settles out of court rather than go through the expense of a trial and then pay the increasingly large judgments that juries award to plaintiffs. Defamation suits cost Ireland's newspapers and broadcasters tens of millions of Euros every year. As a result, lawyers are kept on staff to advise on everything from story ideas to book manuscripts. "When in doubt, leave it out," has become editorial wisdom. The media keeps one eye on the courtroom and the other on distributors and stores, some of which have refused to carry publications for fear that they too could be sued for libel.

Defamation has not chilled the Irish press entirely, but it has made investigative journalism difficult. Veronica Guerin's exposés about the Irish drug underworld in The Sunday Independent are a case in point. Naming persons as drug dealers is a sure-fire way to elicit a libel suit in Ireland, unless, that is, the criminals explicitly comment on allegations made against them. So despite being threatened, beaten, and even shot, Guerin persisted in confronting drug dealers to get them to say something that she could report in the newspaper. Mostly Guerin used nicknames to identify the criminals, making sure not to use details that would make them readily identifiable. This strategy averred libel suits, because in order to sue, the criminals would have to prove that they were the persons who were nicknamed. In 1995, Guerin received the 1995 International Press Freedom Award from the Committee to Protect Journalists. The following year she was shot to death.

According to Irish law, defamation is the publication of a false statement about a person that lowers the individual in the estimation of right-thinking members of society. The Defamation Act of 1961 does not require the plaintiff to prove that the reporter was negligent or that the reporter failed to exercise reasonable care. The plaintiff does not even have to give evidence that he or she was harmed personally or professionally: the law assumes that false reports are harmful. The plaintiff merely has to show that the offensive words referred to him or her and were published by the defendant. It is up to the defendant to prove that the report is true.

The truth of media reports can be hard to prove. In 2002, John Waters, a columnist for the Irish Times , sued The Sunday Times of London for an article written by gossip columnist Terry Keane. The article was about a talk that Waters had given before a performance of the Greek tragedy Medea . Keane called Waters' talk "a gender-based assault," and added that she felt sorry for Waters' daughter: "When she becomes a teenager and, I hope, believes in love, should she suffer from mood swings or any affliction of womanhood, she will be truly goosed. And better not ask Dad for tea or sympathy… or help." Waters said that the article tarnished his reputation as a father, and the jury agreed, awarding him 84,000 euro in damages plus court costs.

As this case shows, even journalists are not reluctant to sue for libel in Ireland. But other groups sue more frequently. Business people and professionals, particularly lawyers, file libel suits most often; they are followed by politicians. Indeed, Irish libel laws favor public officials and civil servants, who can sue for defamation at government expense. If they lose, they owe the government nothing, but if they win, they get to keep the award.

Two strategies are under consideration to reform libel law in Ireland. The first is legislative. National Newspapers of Ireland (NNI) advocates changes in libel law in exchange for formal self-regulation. According to NNI, the Irish public would be better served by having the courts be the forum of last, rather than first, resort in defamation cases. NNI would like to see a strong code of ethics that would be enforced by the ombudsmen of individual media if possible and by a country-wide press council if necessary. But this system can be established only with libel reform, because as the law stands now, a newspaper that publishes an apology is in essence documenting evidence of its own legal liability.

The second strategy to reform libel law in Ireland is judicial. Civil libertarians want an Irish media organization to challenge a libel judgment all the way to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, a court to which Ireland owes allegiance by treaty. If the Irish government loses its case in the Strasbourg court, it is obliged to change its laws to conform to the ruling. Many civil libertarians pin their hope for significant libel reform upon the Strasbourg court because it has ruled that excessive levels of defamation awards impinge free expression.

Despite these strategies for libel reform, the Defamation Act of 1961 still stands because politicians tend to view the media with skepticism and have grave doubts about the sincerity and efficacy of media self-regulation. The Irish public, meanwhile, tends to believe that the media want libel reform more for reasons of self interest than for public service. Change, therefore, is slow. Political scientist Michael Foley fears that "the Irish media will remain a sort of lottery in which many of the players win. Freedom of the press will continue to be the big loser."

Censorship

The Irish Constitution simultaneously advocates freedom of expression and, by forbidding expression that is socially undesirable, permits censorship: "The education of public opinion being, however, a matter of such grave import to the common good, the State shall endeavour to ensure that organs of public opinion, such as the radio, the press, the cinema, while preserving their rightful liberty of expression, including criticism of Government policy, shall not be used to undermine public order or morality or the authority of the State." The Constitution also says, "The publication or utterance of blasphemous, seditious, or indecent matter is an offence which shall be punishable in accordance with law." Accordingly, the government has enacted and rigorously enforced several censorship laws including Censorship of Film Acts, Censorship of Publications Acts, Offenses Against the State Acts, and the Official Secrets Act.

The history of censorship in Ireland is also a history of diminishing suppression. A case in point is the 1997 Freedom of Information Act, which changed the longstanding Official Secrets Act, under which all government documents were secret unless specified otherwise. Now most government documents, except for those pertaining to Irish law enforcement and other subjects of sensitive national interest, are made available upon request. The number of requests for information under the Freedom of Information Act has increased steadily since the law was passed.

The Censorship of Publications Acts of 1929, 1946, and 1967 have governed the censorship of publications. The Acts set up a Censorship and Publications Board, which replaced a group called the Committee of Enquiry on Evil Literature, to examine books and periodicals about which any person has filed a complaint. The Board may prohibit the sale and distribution in Ireland of any publications that it judges to be indecent, defined as "suggestive of, or inciting to sexual immorality or unnatural vice or likely in any other similar way to corrupt or deprave," or that advocate "the unnatural prevention of conception or the procurement of abortion," or that provide titillating details of judicial proceedings, especially divorce. A prohibition order lasts up to twelve years, but decisions made by the Board are subject to judicial review.

The first decades under censorship laws were a time of strong enforcement, thanks in large measure to the Catholic Truth Society, which was relentless in its petitions to the Censorship Board. Before the 1980s, hundreds of books and movies were banned every year in Ireland, titles including such notable works as Hemingway's A Farewell To Arms , Huxley's Brave New World , Mead's Coming Of Age In Samoa , and Steinbeck's The Grapes Of Wrath. Playboy magazine was not legally available in Ireland until 1995. The English writer Robert Graves described Ireland as having "the fiercest literary censorship this side of the Iron Curtain," and the Irish writer Frank O'Connor referred to the "great Gaelic heritage of intolerance."

Although the flood of censorship has slowed to a trickle, recent cases serve as a reminder that censorship efforts still exist in Ireland today. A Dublin Public Library patron complained to the Censorship Board that Every Woman's Life Guide and Our Bodies, Ourselves contained references to abortion. The library removed the books because, according to a Dublin Public Library spokesperson, "We're not employed to put ourselves at legal risk." In 1994, the Oliver Stone film Natural Born Killers was banned. In 1999, the Censorship Board banned for six months the publication of In Dublin , a twice-monthly events guide, because the magazine published advertisements for massage parlors. The High Court chastised the board for excessiveness and lifted the ban on condition that the offending advertisements would appear no longer.

The potential for censorship in Ireland is real, but circumscribed. Not only have recent government censors shown restraint in inverse proportion to the power they have on paper, but most of the censorship that they have exercised is over blatant pornography. Furthermore, Ireland is awash with foreign media, so parochial censorship is likely to be countered readily by information from the UK, Western Europe, and the United States.

State-Press Relations

Like other western European countries, Ireland has an established free press tradition. The Irish Constitution guarantees "liberty of expression, including criticism of Government policy" but makes it unlawful to undermine "the authority of the State." Although not absolute, press freedom is fundamental to Irish society.

The extent to which the Irish media exercise their right to criticize government policy is a matter of perspective. Many politicians and government officials believe that the press is critical to the point of being downright carnivorous. Garrett Fitzgerald, former prime minister of Ireland, agreed with Edward Pearce of New Statesman & Society who said that the media "devour our politicians, briefly exalting them before commencing a sort of car-crushing process." However, others disagree, complaining that the press acquiesces to the wishes of the government. "The relationship between the media, especially the broadcast media, and the political establishment is the aorta in the heart of any functioning democracy. Unfortunately, in Ireland this relationship has become so profoundly skewed that it threatens the health of the body politic," Liam Fay complained in the London Sunday Times . While RTÉ [Radio Telefís Éireann] will never become "the proverbial dog to the politicians' lamppost," said Fay, "the station has a responsibility to do more than simply provide a leafy green backdrop against which our leaders and would-be leaders can display their policies in full bloom. Yet this is precisely what much of RTÉ's political coverage now amounts to."

Revelations in the 1980s that the government had tapped the phones of three journalists for long periods of time helped to spur further adversity between news reporters and the government. Because the government had tapped the phones of Geraldine Kennedy of the Sunday Tribune and Bruce Arnold of the Irish Independent without proper authorization in an attempt to track down cabinet leaks, the High Court awarded£20,000 each to Kennedy and Arnold and an additional£10,000 to Arnold's wife. Vincent Brown of Magill magazine, whose phone was tapped when his research had put him in touch with members of the IRA, settled out of court in 1995 for £95,000.

The government office established to deal with the media is Government Information Services (GIS), made up of the Government Press Secretary, the Deputy Government Press Secretary, and four government press officers. Charged with providing "a free flow of government-related information," GIS issues press releases and statements, arranges access to officials, and coordinates public information campaigns.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

The government of Ireland has a cooperative relationship with foreign media. The Department of Foreign Affairs keeps domestic and international media up to date on developments in Irish foreign policy by publishing a range of information on paper and electronically, providing press briefings, and arranging meetings between foreign correspondents and the agencies about which they want to report.

Opposition to foreign media in Ireland thus comes not from the government but rather from Irish publishers, who complain of unfair competition from British media companies. One complaint involves below-cost selling. Irish publishers protest that their British competitors sell newspapers in Ireland at a cover price with which Irish newspaper companies cannot compete. Irish publishers also complain that the 12.5 percent valued added tax (VAT) on newspaper sales in Ireland causes an unfair burden. Huge British companies, which have no VAT tax at home, are able to absorb the Irish tax more easily than Irish publishers, who lack the cushion British publishers enjoy. Irish publishers claim that below-cost selling and the VAT tax have helped ensure that a significant portion of daily and Sunday newspapers sold in Ireland are British.

Besides competing with imported media, Irish companies are increasingly finding themselves competing with foreign-owned companies at home. Scottish Radio Holdings owns Today FM, the national newspaper Ireland on Sunday , and five regional papers. CanWest Global Communications has a 45 percent stake in TV3, as does Granada, the largest commercial television company in the UK. And Trinity Mirror, the biggest newspaper publisher in the UK and the second largest in Europe, owns Irish Daily Mirror , The Sunday Business Post , Donegal Democrat , and Donegal Peoples Press . Until recently, foreign ownership of Irish media has been limited. But the Irish media market is attractive and there is no legislation that prevents foreign ownership of Irish media, so the sale of Irish media properties to foreign (primarily British) companies is expected to continue.

News Agencies

Because Ireland is a small country, there are no domestic Irish news agencies. Irish media use international news agencies and their own reporters for news gathering. Although some of the major international agencies have a bureau in Dublin—representatives include Dow Jones Newswires, ITAR-TASS, Reuters, and BBC— many do not, choosing instead to rely upon their London correspondents to report on Ireland as stories arise.

Broadcast Media

Since the 1920s, broadcasting in Ireland has been dominated by RTÉ, a public service agency that is funded by license fees and the sale of advertising time. RTÉ runs four radio and three television channels. Radio 1 is RTÉ's flagship radio station. Begun in 1926, it broadcasts a mixture of news, information, music, and drama. RTÉ's popular music station 2 FM is known for its support of new and emerging Irish artists and musicians. Lyric FM is RTÉ's 24-hour classical music and arts station. The fourth RTÉ station is Radió na Gaeltachta, which was established in 1972 to provide full service broadcasting in Irish. RTÉ also operates RTÉ 1, a television station that emphasizes news and current affairs programming; Network 2, a sports and entertainment channel; and TG4, which televises Irish-language programs. RTÉ is currently in the process of launching four new digital television channels: a 24-hour news and sports channel, an education channel, a youth channel, and a legislative channel.

The funding for RTÉ has been a source of contention among Ireland's commercial broadcasters, who complain that license fees contribute to unfair competition. RTÉ receives license fees to support public service broadcasting even though RTÉ's schedule is by no means exclusively noncommercial. Commercial broadcasters, by contrast, are required to program news and current affairs, but without any support from license fees. Meanwhile, because the government is loath to increase license fees, RTÉ is finding it must rely more upon advertising even as increasing competition among broadcasters is making advertising revenue more difficult to obtain.

Besides RTÉ's public stations, there are many independent radio and television stations in Ireland. There are 43 licensed independent radio stations in Ireland. In addition to the independent national station, Today FM, there are 23 local commercial stations, 16 non-commercial community stations, and four hospital or college stations. Although many of the independent stations broadcast a rather stock set of music, advertising, disk jockey chatter, and current affairs programs, some serve their communities with unique discussion programs.

Pirate radio stations have existed in Ireland as long as Ireland has had radio. Today about 50 pirate stations operate throughout Ireland. The Irish government tolerates these stations as long as they do not interfere with the signals of licensed broadcasters.

The only independent indigenous television station in Ireland is TV3. Although licensed to broadcast in 1988, TV3 did not begin broadcasting until 1998. It took ten years to find financial backing, 90 percent of which finally came from the television giants Granada (UK) and CanWest Global Communications (Canada). TV3 produces few programs in house; most TV3 programs are sitcoms and soap operas imported from the United States, UK, and Australia.

More than half of Irish households subscribe to cable TV. (Cable penetration in Dublin is an astounding 83 percent.) Those who subscribe to cable receive the three Irish television channels, four UK channels, and a dozen satellite stations. Two companies, NTL and Chorus, control most cable TV in Ireland. The US-owned NTL is the largest. Chorus Communication is owned by a partnership of Independent News and Media, the Irish conglomerate, and Liberty Media International, which is owned by AT&T.

The only provider of digital satellite in Ireland is Sky Digital, operated by British Sky Broadcasting (BSkyB). Twenty percent of households in Ireland subscribe to Sky Digital. Sky offers more than 100 broadcast television channels plus audio music and pay-per-view channels. Beginning with two matches between middleweight boxers Steve Collins and Chris Eubank in 1995, and quickly followed by golf tournaments and even an Ireland-USA rugby game, Sky has bought exclusive rights to Irish sports events for broadcast on a pay-per-view basis. Sky's purchases have had the effect of making certain events exclusive that had customarily been broadcast freely. Irish viewers can no longer expect to see every domestic sports event without paying extra.

All information transmitted electronically, from broadcast to cable to satellite and Internet, is under the authority of the Broadcasting Commission of Ireland (BCI), as set forth in the Broadcasting Act of 2001. BCI is responsible for the licensing and oversight of broadcasting as well as for writing and enforcing a code of broadcasting standards.

Electronic News Media

Ireland today is a center for the production and use of computers in Europe. One-third of all PCs sold in Europe are made in Ireland, and many software companies have plants there. Indigenous companies include the Internet security firm Baltimore Technologies and the software integration company Iona Technologies.

The longest running Internet news service in the world is The Irish Emigrant, which Liam Ferrie began as an electronic newsletter in 1987 to keep his overseas colleagues at Digital Equipment Corporation informed of news from Ireland. Today, The Irish Emigrant reaches readers in over 130 countries. A hard copy version has appeared on green newsprint in Boston and New York since 1995. The Irish Internet Association gave Ferrie its first Net Visionary Award in 1999.

Virtually all broadcasters and newspapers in Ireland have a web page. The Irish Times launched its website in 1994 and transformed it into the portal site, Ireland.com , four years later. This website attracts 1.7 million visits from 630,000 unique users each month, a rate in Ireland second only to the site of the discount airline Ryanair. Following the trend among content-driven web sites throughout the world, Ireland.com began to charge for access to certain sections of the site in 2002. Ireland's Internet penetration rate was 33 percent in 2002; the penetration rate in Dublin was 53 percent.

Education & TRAINING

Journalism education is becoming increasingly common in Ireland. At least three institutions of higher education offer degrees in journalism. Dublin City University's School of Communications offers several undergraduate and graduate degrees including specialties in journalism, multimedia, and political communication. Dublin Institute of Technology offers a B.A. degree in Journalism Studies and a Language, designed to educate journalists for international assignments or for dual-language careers at home. Griffith College Dublin offers a B.A. degree in Journalism & Media Communications as well as a one-year program to prepare students for a career in radio broadcasting. Irish students who need financial assistance in order to study journalism can apply for the Tom McPhail Journalism Bursary, a scholarship administered by the National Union of Journalists in honor of the Irish Press and Granada Television news editor who co-founded the short-lived Ireland International News Agency.

Summary

Given its relatively small population of 3.8 million, the Republic of Ireland has a rich media environment. It is served by 12 national newspapers—four dailies, two evenings, five Sundays, and one weekly—and by more than 60 regional newspapers. There are more than 150 indigenous consumer magazines and nearly 50 indigenous book publishers. Ireland has four national television stations, five national radio stations, and dozens of regional radio stations. There is a growing Irish presence on the Internet as well as an increasing Internet penetration rate in Ireland. There are also a plethora of imported books, magazines, and newspapers, as well as radio and television channels available through cable and satellite. Ireland's media environment is both populous and diverse, essential qualities for any healthy democracy.

Politically, the media in Ireland is as free from government interference as it has ever been. Before the 1990s, the Censorship Board banned hundreds of books and movies every year, a pattern that inhibited creativity at home and attempts at importing from abroad. Today the Censorship Board screens for pornography, but little more. Literature and film are free to circulate.

The government has also granted the media far wider access to its records. Until recently government records in Ireland were presumed to be private and unavailable to the public. But with the Freedom of Information Act of 1997, the press—or any Irish citizen—can now make formal requests to see government records, and with very few exceptions, those requests will be granted. The Freedom of Information Act has had the effect of encouraging more investigative reporting.

Libel, however, continues to be a problem for the press in Ireland. Libel suits are relatively easy to win in Ireland because the plaintiff has only to prove publication of defamatory statements, not their falsity, which in Ireland is the defendant's task. Furthermore, the more public the figure in Ireland, the greater the award for defamation that juries are likely to give. Such conditions make investigative reporting risky and, with the cost for lawyers on retainer, expensive. Nevertheless, the national Irish media continue to criticize government officials and discuss important social, political, economic, and religious issues. The chilling effect seems more potential than real at this point.

The media in Ireland are also facing economic challenges. One is globalization. Irish media confront stiff competition from magazines, books, and newspapers, as well as radio and television programs, that pour into Ireland from transnational UK companies with such economies of scale that they can undersell indigenous Irish products. Increasingly, media companies from the UK are buying Irish media, and large Irish companies are doing the same, so that there are fewer and fewer owners of the media. This increasing concentration is likely to diminish diversity in media content.

The public service tradition in Irish broadcasting is experiencing similar difficulties. RTÉ relies upon license fees supplemented with advertising revenue to fund its programming, which ranges from news and current affairs to entertainment and cultural programming both in English and in Gaelic. At the same time, RTÉ is facing increasing competition from commercial broadcasters that offer popular, lighter fare. Under these circumstances, RTÉ audiences will decline, making it both more difficult to generate advertising revenue and to justify increased license fees. Although RTÉ operates under a mandate to offer programs that serve viewers rather than merely satisfy them, the pressure on RTÉ is to compete

The trends toward concentration and commercialization of the media in Ireland are indeed powerful, but their effects are likely to be mitigated, at least in part, by other forces. One of these forces is technology. The Internet, with its small but growing presence in Ireland, offers the very real opportunity to contribute ideas to the public sphere that have little apparent commercial appeal. Businesses and established publishers and broadcasters dominate the Internet, but not exclusively, so the Internet will continue to be available as an avenue for dissent and other alternative expression. Furthermore, as long as the desire to preserve, promote, and explore Irish culture and language is strong, unique, and compelling, Irish communications will continue to circulate, sometimes commercially and sometimes as the result of government planning and investment.

Significant Dates

- 1997: Freedom of Information Act passed.

- 1998: TV3, Ireland's first commercial television station, began broadcasting.

- 2001: Broadcasting Act passed.

Bibliography

Farrell, Brian. Communications and Community in Ireland . Dublin: Mercier, 1984.

Horgan, John. Irish Media: A Critical History Since 1922 . London: Routledge, 2001.

Kelly, Mary J. and Barbara O'Connor, eds. Media Audiences in Ireland: Power and Cultural Identity . Dublin: University College Dublin Press, 1997.

Kiberd, Damien, ed. Media in Ireland: The Search for Ethical Journalism . Dublin: Four Courts, 1999.

——. Media in Ireland: The Search for Diversity . Dublin: Four Courts, 1997.

Oram, Hugh. The Newspaper Book: A History of Newspapers in Ireland, 1649-1983 . Dublin: MO Books, 1983.

Woodman, Kieran. Media Control in Ireland, 1923-1983 . Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1985.

John P. Ferré

Joe O'Dwyer

in the hotel industry a year ago an the crinal case actually is being on trial in cort no 5 i could

not get any information on line its a pitty, hope the employers in the hotel industies in mauritius noms exactly what does hospitaliy means.