Lebanon

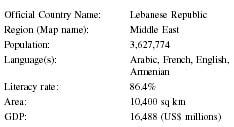

Basic Data

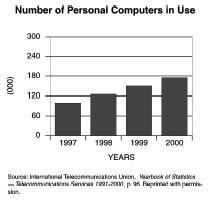

| Official Country Name: | Lebanese Republic |

| Region (Map name): | Middle East |

| Population: | 3,627,774 |

| Language(s): | Arabic, French, English, Armenian |

| Literacy rate: | 86.4% |

| Area: | 10,400 sq km |

| GDP: | 16,488 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Daily Newspapers: | 13 |

| Total Circulation: | 220,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 96 |

| Number of Nondaily Newspapers: | 2 |

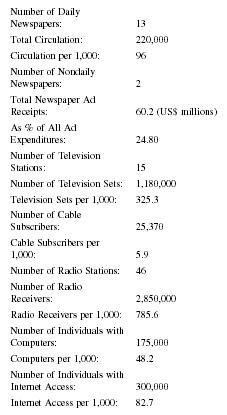

| Total Newspaper Ad Receipts: | 60.2 (US$ millions) |

| As % of All Ad Expenditures: | 24.80 |

| Number of Television Stations: | 15 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 1,180,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 325.3 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 25,370 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 5.9 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 46 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 2,850,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 785.6 |

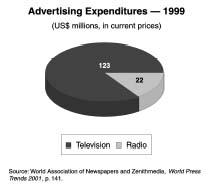

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 175,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 48.2 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 300,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 82.7 |

Background & General Characteristics

Lebanon ( Lubnan ) or the Lebanese Republic ( Al Jumhuriyah al Lubnaniyah ) can be thought of as, "a land in-between." This definition well describes its geographical positioning, political situation, religious compilation, and communication and press orientation. Noting increasing connections with international bodies and an increasing respect for international norms, it is expected that these factors will increase the stability of the country's politics and infrastructure, facilitating development through all levels of society and engendering a better place to live for its citizens.

Country Geography

Geographically, Lebanon can be found bordering the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea. It is also bordered by Israel (south) and Syria (north and west). Lebanon has felt intense political pressures from these two neighbors throughout its history. The outside political pressure has been intensified because many Lebanese identify themselves far more readily by their local, tribal/ethnic, and religious affiliations than by their national association.

Lebanon (population between 3.6 and 4.3 million) is normally divided into four roughly parallel topographical zones that run the length of the country. One region is the Mediterranean coastal plain located primarily in the north, which is home to the major cities of Lebanon including Tripoli, Jubail (Byblos), Beirut, Saida (Sidon), and Sur (Tyre). The mountain ranges of Lebanon receive significant snowfall during the year and provide a beautiful panorama for surrounding areas. The presence of snow seems to have been deemed important enough to have played an integral role in the very naming of the country; Lebanon means white ( laban ) in Aramaic. And as well as having the rarity of snow, Lebanon has one other rarity in the Middle East—no desert.

Country History

Lebanon has been active as an entity since the ancient world; however, for much of its history, it has been a war zone for would be conquerors, usurpers, and overlords. It was the homeland for the Phoenicians/Canaanites (c.2700-450 B.C.) and also served as host to the Babylonians, Egyptians, Romans, and others. Yet, despite the desires of its nemeses, Lebanon remained free of total subjugation from would-be conquerors and provided perennial refuge to persecuted racial and religious minorities from all over the region due to its mountainous, rugged terrain. Thus, early on in its history from the influx of both conquerors and persecuted Lebanon gained a type of cosmopolitanism, becoming composed of multiple ethnic backgrounds and religious orientations.

In the ninth and tenth centuries, besides settled Sunni populations along the coasts, Mitwali (Shi'a) began to establish communities in the mountain area just off Lebanon's coast. Then in the eleventh century, the Druze also established enclaves as well. The years 1291 through 1516 saw the Mamluk—a warrior caste made up of Turks, Mongols, and Circassians—period of rule. While the Mamluk's ruled over Egypt, Syria, and other Arabian holy areas, the Lebanese, through persistent political maneuvering, continued to maintain autonomous functioning. The Maronites of the province fared especially well during this period due to their contacts with Italy and the Roman Curia. The Druze and Mitwali, who had not established the same contacts, were not privy to the same favoritism. This created discontent against the Maronites. So, in the thirteenth century, taking advantage of Mamluk preoccupation with the Mongol threat from Persia, the Druze and Shi'a revolted against the Maronites creating havoc in central Lebanon.

The year 1516 began the rule of the Ottomans. It was in this year that they conquered Syria from the Mamluks and incorporated Lebanon into their empire. Yet, even with the Ottomans, Lebanon was allowed to function relatively autonomously. During a weak point in Ottoman rule, Fakir ad-Din II (1586-1635) of the Druze House of Ma'an attempted complete independence from the Ottomans and succeeded for a number of years, but it did not last and he was eventually executed in 1635 in Constantinople. After this, the House of Ma'an was succeeded by the House of Shihab. This dynasty enjoyed a two-hundred-year rule, ending with the exile of Bashir II in 1840.

The Ottomans then set up a system of Kaimakams— one Druze and one Maronite—to rule under the Turkish pashas of Beirut and Sidon. This began the reemergence of Maronites to power, which led to years of sectarian violence, which the Ottomans did little to curtail. The Ottomans lack of interest in Lebanon turned out to be the Europeans gain.

The European powers, sensing an opportunity, began to move beyond the traditional trading activities that they had engaged in for centuries with Lebanon and began to establish political/military alliances with particular ethnic factions. The French formed with the Maronite Christians, the Russians with the Orthodox Christians, and the British with the Druze and the Sunnis. Thus, after 1860, the Europeans were able to externally control some of the Lebanese.

European influence proved strong enough to set up an international committee consisting of Austria, France, Great Britain, Prussia, Russia, and the Ottomans to facilitate the restoration of order inside Mount Lebanon. Violence was curtailed through the policies arising from this conference, and the period of 1860-1914 became known as a renaissance for Lebanese culture. Roads and railroads were built, Arab literature and learning blossomed, and overall the culture simply flourished. Beirut transformed from a Sunni town into a coastal cosmopolitan commercial center. Increasing prosperity was experienced by many and, very importantly, this period led to exceptionally strong feelings of Lebanese identity and Lebanese leadership for the Arab nationalist movement among the people of Mount Lebanon.

After World War I the League of Nations mandated the five provinces of the Ottoman Empire to France—this mandated area today makes up modern Lebanon. This newly formed area, bequeathed to France in 1920, was called "Grand Liban." At its outset the territory was evenly divided between Christian and Muslim populations. However, due to French ties with Maronite Christians, the tables of favoritism flipped once again and the Maronites became the new ruling power of the area. The Druze and Shi'ites detested this turn-of-events. To combat opposition and consolidate their authority, the Maronites established associations with the Sunnis and other factions of reasonably placid orientation. Though there were periodic outbursts of violence over French rule and Maronite governing up to the beginning of World War II, these proved inconsequential due to the large showingof French military that remained stationed in the area. Yet once again, despite overarching rule by an outside power, Lebanon remained an autonomously governed area, only subject to veto on its ruling decisions.

On May 26, 1926, French Lebanon became the Republic of Lebanon ( Al Jumhuriyah al Lubnaniyah ). The initial constitution of the Republic proved an unsuccessful document by which to govern, but through all of its numerous revisions, up to current times, it has remained the principle document organizing the Lebanese government. Importantly, in November 1941, France formally declared Lebanon a sovereign independent state, although France continued to maintain a strong military presence in the state. Then, in 1943 due to constitutional reform measures being taken in Lebanon, the French arrested the President of Lebanon. This nefarious act united the various factions of Lebanese politicians, as well as British and Americans who took the side of the Lebanese. France was forced to acquiesce to Lebanese demands for complete independence and all of its troops completely withdrew on December 31, 1946 (Evacuation Day).

Lebanon has continued to see hard times since its independence. However, up until 1975 a modicum of solid national consistency was maintained in the country. Its position on the Mediterranean coast with a number of seaports has made it an important economic player in the area, which has also helped to increase outside interest in its stability and helped to attract foreign aid for development.

Lebanon's long and devastating civil war (1975-1991) consisted of numerous factions vying for often weakly defined and definitely elusive goals. The factions included: The Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), Shi'ites (Amal and Hezbollah/Hizbullah), Maronite, Phalangist, Lebanese National Movement (LNM), and Lebanese Forces (LF). In addition to Lebanon's internal fighting, concurrent Israeli and Syrian incursions in the country further exacerbated the destructive and chaotic nature of the time. Its people and infrastructure bore heavy losses. Lebanon is recovering from these losses, but it is doing so slowly. The future is open and looks promising but could hold either promise or peril for this country.

State of the Press

With all of its historical difficulties, Lebanon has managed to produce a highly literate, educated, and critical populace. As reported by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency in 2002 using a 1997 estimate, an average of 86.4 percent of the Lebanese population is considered literate (males, 90.8 percent; females, 82.2 percent). A significant factor driving this educational process is the presence of relatively diverse and sophisticated press and media systems that facilitate continuing education of the Lebanese populace above and beyond traditional schooling. As well, Lebanon has had a positive relationship with the press due to its ethnically diverse population base—each segment requiring papers focused to its particular interests. This niche marketing of papers has allowed for a vibrant dialogue to occur in the Lebanese political and social scene, enough so that one historian has designated Lebanon as the "true cradle of Arab journalism." With multiple opinions available to them, the Lebanese have typically become savvy enough readers/listeners/viewers to gravitate back and forth between papers/channels depending upon which political or social slant they want to read/hear/view. Often, they can tune into a random station generating a broadcast with news content and, within a small portion of time, can suggest the political orientation of the message, some of the history driving the issue being discussed, and some of the key figures related to the topic.

Lebanese traditions with the press and the media date back more than 150 years. The first newspaper, Hadikat Al-Akhbar ( The Garden of News ), was published in Lebanon in 1858 through the direction of Khalil El-Khouri and was followed two years later in 1960 by three other papers: Nafeer Souria ( The Call of Syria ) published by Butrus Al-Bustani in Lebanon, Aj-Jawa'ib (The Traveling News) published in Istanbul, and Barid Paris (Paris Mail) published in France. The time of the Ottoman Empire was an era of significant persecution for journalists in Lebanon. Some of the journalists ended up fleeing to Egypt and founding some of the country's major papers like Al-Ahram and Al-Musawar . After the Ottomans, the French enacted even harsher press laws. Yet, the Lebanese press was resilient and, by 1929, there were 271 papers with a majority calling for national independence from external oppressive regimes.

At the end of World War II, Lebanon finally gained full independence but, fascinatingly, the first indigenous ruling regime enacted even harsher press laws than the French. However, again the press refused to bow to pressure and, by 1952, a popular revolt was fomented against the government that led to relaxed press laws. In 1962 laws were enacted that guaranteed freedom of the press in Lebanon. Civil war was the next trial that the Lebanese press had to endure during the period 1975-1991. Yet, emerging from the bloody chaos of the war in 1991, the Lebanese press had 105 licensed political publications comprised of 53 dailies, 48 weeklies, and 4 monthly magazines. As well, more than 300 non-political publications were being published. The Lebanese press is tenacious and stalwart, and it continually grows.

In the 2000s, An-Naha r or Al-Nahar and Al-Diyar are arguably the most influential daily papers in terms of raw circulation numbers. Al-Nahar is more of a prestigious publication, and Al-Diyar is more populist in orientation. Al-Safir and Al-Anwar are second runner-ups. For all of these papers, the readership ratio is roughly two to one favoring men over women; this is, however, reversed for one paper, L'Orient le Jour , where more women than men compose its reader base.

Dailies

Almost every publication from Lebanon is published in the capital city of Beirut. Lebanese news is published in four languages: Arabic, French, Armenian, and English. The leading Arabic dailies include: An-Nahar ( The Day ), Al-Safir ( The AmbassadorAl-Diyar or Ad-Diyar( The Homeland ), Al-AmalThe HopeLisan ul-Hal ( The Organ ), Sada LubnanEcho of LebanonAl-Hayat ( The Life ), and Al-AnwarThe Lights ).

An-Nahar has a circulation of 45,000. It was founded in 1933 as an independent, moderate right-of-center paper, attempting to speak on behalf of the Greek Orthodox community and appeal to a broader audience as well. It has been noted as being a watchdog for public rights and an excellent source for reporting diverse and divergent views in a professional manner. Al-Safir , founded in 1974, has a circulation of 50,000. As a political paper, it represents Muslim interests with strong news coverage and background articles, strongly promotes Arab nationalism, and is pro-Syrian. Al-Diyar or Ad-Diyar is unlike most of the competition because it comes out on Sundays. The paper is strong in classified advertising and is widely read, but its sensationalist style has often lacked professional ethics. Al-Amal , founded in 1939, and with a circulation of 35,000, is the voice of the Phalangist party. Lisan ul-Hal has a circulation of 33,000 and was founded in 1877; Sada Lubnan has a circulation of 25,000 and was founded in 1951; and Al-Hayat has a circulation of 31,034 and was founded in 1946 as an independent. Al-Anwar , founded in 1959, has a circulation of 25,000. It is published by the famous publishing house of Dar al-Sayyad owned by the Freiha family; the paper typically attempts to appeal to wide readership and is noted for stressing production quality and professional journalism.

Other Arabic papers include: Al-Harar, Al-Bairaq (The Banner), Bairut (Beirut), Ach-Chaab (The People), Ach-Charq or Al-Sharq (The East), Ach-Chams (The Sun), Ad-Dunya (The World), Al-Hakika (The Truth), Al-Jarida (The [News] Paper), Al-Jumhuriya (The Republic), Journal Al-Haddis, Al-Khatib (The Speaker), Al-Kifah al-Arabi (The Arab Struggle), Al-Liwa (The Standard), Al-Mustuqbal, An-Nass (The People), An-Nida (The Appeal), Nida' al-Watan (The Call of the Home-land), An-Nidal (The Struggle), Raqib al-Ahwal (The Observer), Rayah (Banner), Ar-Ruwwad, Sawt al-Uruba (The Voice of Europe), Telegraf-Bairut, Al-Yaum (Today), and Az-Zamane or Al-Zaman .

With Lebanese Arabs making up 95 percent of the population and with a Muslim religious orientation of various persuasions (including Shi'a, Sunni, Druze, Isma'ilite, Alawite or Nusaryi) making up roughly 70 percent of the faith perspective, it should be apparent why there is a plethora of Arabic newspapers compared to a small minority of other dailies. The other dailies include three Armenian, two French, and one English. The Armenian papers are: Ararat , Aztag , and Zartonk . The French papers are L'Orient-Le Jour (from the publishers of Al-Nahar and noted for well-researched background information, intelligent feature stories, and thoughtful editorials) and Le Soir . Since a significant number of the country's elite speak French, the French-language newspapers have a higher degree of influence than one might expect. The English paper is the Daily Star .

Weeklies and other Periodicals

Along with a rich and robust plate of dailies, there is also a burgeoning repertoire of Lebanese weeklies. The weeklies include: Al-Alam al-Lubnani ( The Lebanese World ), AchabakaThe Net ), Al-Ahad ( SundayAl-AkhbarThe NewsAl-Anwar Supplement , DabbourAd-DyarAl-Hadaf (The Target), Al-Hawadess ( EventsAl-HiwarDialogue ), Al-Hurriya ( Freedom ), Al-MoharrirThe LiberatorAl-Ousbou' al-Arabi ( Arab Week ), Sabih al-KhairGood Morning ), and Samar .

Al-Alam al-Lubnani , founded in 1964, has a circulation of 45,000; it is published in Arabic, English, French, and Spanish, and contains matters of politics, literature, and social economy. Achabaka , founded in 1956, has a circulation of 108,000, while Al-Ahad , a political paper, has a circulation of 32,000. Al-Akhbar , the voice of the Lebanese Communist Party, has a circulation of 21,000. The Al-Anwar Supplement , a cultural-social paper, has a circulation of 90,000, while the Ad-Dyar , a political paper, has a circulation of 46,000. Al-Hadaf , founded in 1969, is the voice for the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). Al-Hawadess has a circulation of 120,000; Al-Hurriya has a circulation of 30,000 and is the voice of the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine). Al-Ousbou'al-Arabi , a political and social paper, has a circulation of 87,000 throughout the Arab world, while Samar is published for the teenage audience.

Some selected examples of periodicals other than weeklies include: Alam at-Tijarat ( Business World ), Arab Construction World , Arab Defense JournalArab Economist , Al-Intilak ( Outbreak ), Fairuz LebanonAl Computer, Communications, and Electronics , Fann at-Tasswir, Al-Mukhtar ( Reader's Digest ), Rijal al-Amal ( The Businessman ), Tabibok ( Your Doctor ), and At-Tarik ( The Road ).

Economic Framework

As noted above, at least 86.4 percent of the Lebanese population older than fifteen years of age is estimated as literate; thus, illiteracy is not an impediment to newspaper readership. Due to a large proportion of urbanization (83.7 percent), distribution is also not a typical impediment. However, price and time can be significant obstacles. The most respected newspapers can cost up to US$1.32. In a country where the average GDP is US$5,000 and unemployment is at 18 percent, costs can tend to add up quickly. Placed comparatively next to the monthly costs of television subscription, the expense of newsprint becomes more obvious. On a monthly basis, purchasing a newspaper 6 days a week costs about US$29 a month while linking up to satellite television costs between US$10-12. And then even beyond the concern of cost is the concern of time. Those who have been able to find employment are more concerned with getting there and getting home than with picking up a paper. Jamil Mroue of the Daily Star has suggested that to combat this dilemma of cost and time, home delivery of papers should be increased, upping readership (which currently hovers at only 50 percent of the population according to the British Broadcasting Service) and at the same time lowering cost by increasing distribution.

Of course, a significant aspect creating the economic woes facing Lebanon was the civil war that raged from the 1970s until the early 1990s, which devastated much of the infrastructure of Beirut and also took its toll through civilian death. The war also caused what has come to be known as "brain-drain" or the mass migration of educated intelligentsia to other countries offering better rates of pay and social benefits. Specifically with the press/media, numbers of journalists were killed during the fighting and numerous offices/studios/printing plants were bombed, looted, and/or otherwise sabotaged.

During the beginning years of the war, when fighting was extremely intense, many publications were forced to shut down. However, even in the darkest hours about 24 newspapers and other periodicals were still being regularly published. Also, as soon as the fighting lessened, some of the other publications almost immediately resumed schedule. Papers were able to so easily resume because so many of them were privately owned by either individual proprietors or by publishing houses. All of the typical bureaucracy of government was avoided in getting everything back up and running. Still due to lack of external

While it has been a positive experience for Lebanese press to be privatized, due to the niche marketing of much of the industry to specific ethnic-religious enclaves there has also been a narrow margin of profit. As it has been said, while the Lebanese press may be healthy, they certainly are not wealthy. This would normally be something that could be dealt with, but there are extenuating circumstances in the case of Lebanon. There is a legal requirement that any aspiring publisher must be licensed by purchasing an existing title. The government is refusing to issue any new licenses. Thus, there has become a huge market in newspaper publishing licenses, exorbitantly driving up the price to amounts that make it virtually impossible for anyone but a publishing house to undertake starting a new publication—especially since the profit margin is small. For instance, it could easily cost in the realm of US$300,000-400,000 to acquire the license for a weekly. (The price to acquire a daily could easily double that amount.) This creates an economic hurdle brought about by a government decision that is inhibiting press freedom in Lebanon.

As well, due to the small margin of realized profit available to newspapers, many of them are open to bribery or "subsidies with strings attached" from foreign sources. It comes down to being willing to slant the news in someone's favor in order to stay in business. And it is not only corporations or "rogue" nations that have been implicated in this practice—Russian and American sources have been named as well. The same can be said for advertising. Again, because of small margins of profit, newspapers actively seek out advertising dollars. However, it is typically not local merchants buying ad space. The advertising dollars seem to come from outside foreign corporations who often have more than simply a product to sell.

As it currently stands, there are about 23 publishing houses operating in Lebanon producing a significant amount of the print that is sold in the country. One of the larger and more well-known houses is Dar Assayad Group (SAL and International). Dar Assayad, owned by the Freiha family, publishes Al-Anwar; Assayad; Achabaka; Arab Defense Journal; Fairuz Lebanon; Al-Idair; Al Computer, Communications, and Electronics; and Al-Fares . There are also numerous private owners of publications who have held the licenses to such publications for many years, but it has become far less plausible for such private procurement of publishing licenses to continue occurring as the situation stands.

Press Laws

The major laws concerning press and media are the 1962 Press Law and the Audiovisual Media Law (Law 382/94) passed by the parliament in October 1994 and finally applied on September 18, 1996. The 1962 Press Law, which has significant similarities with many other Arab states' press laws, states that nothing my be published that endangers national security, national unity, or state frontiers, or that insults high-ranking Lebanese officials or a foreign head of state. More positive portions of the law, such as Article Nine, state that journalism is "the free profession of publishing news publications." It defines a journalist as anyone whose main profession and income are from journalistic aspects. The 1962 law also set the standard for Lebanese journalists as being at least 21 years of age, having a baccalaureate degree, and having apprenticed for at least four years in journalism. The 1962 Press Law also organized journalists into two syndicates: the Lebanese Press Syndicate (owners) and the Lebanese Press Writers (reporters) Syndicate. As well, a Higher Press Council was created, along with other committees, to consider other issues pertinent to journalists— including devising a retirement plan.

Before and during the civil war of 1975-1991, the 1962 Press Law was rarely enforced, and this was taken advantage of by the press. Upon emerging from the conflict, the government has attempted to become more stringent. In 1994 the government attempted to enforce penalties of detention and fines upon various press establishments but met with significant opposition and gave way under pressure. However, fines and other forms of sanctions remain a significant and ever present threat to press freedom.

Press freedom and media freedom issues often run closely parallel courses. Early in January 1992, the government proposed that any television station wishing to continue its broadcasting not include any "information" programming as that was the purview of the government. The media immediately assailed the government, and the proposal was withdrawn a few days later. Then the government proposed the Audiovisual Media Law of 1994, which did get enacted. It divided television and radio stations into categories related to whether or not they were licensed for broadcasting news and/or political coverage or only entertainment or general concern content. Fascinatingly, this law abolished Lebanon's state broadcasting monopoly. Thus, Lebanon became the first Arab State to authorize private radio and television stations to operate within its borders. However, even though this seems to be a monumental achievement, the downside to this equation is that many of the small operators of illegal stations were closed and influential politicians and corporate conglomerates were the ones who received the bulk of the private licenses. The initial idea with the Audiovisual Media Law was to offer a one-year provisional permit to license applicants and then, if all requirements were met, to bestow a 16-year license. In actuality, licenses were typically immediately granted or denied.

No individual or family is allowed to own more than 10 percent in a television company. Television stations themselves are required to broadcast to the entire country for at least 4,000 hours per year with at least 40 percent of the programming being locally produced. Nothing is allowed that is in the least bit favorable to the establishment of relations with "the Zionist entity." The Audiovisual Media Law is supposedly based upon a premise of seeking to promote balanced news coverage; thus, in any given program there is supposed to be an equal airing of political perspectives ideally providing a balanced orientation. The reality of the situation is of course far from the ideal. In order to monitor and assess whether or not the law is being followed the National Council for Audio-visual Media has been created (CNA). A portion of the controversial aspect of the council's task comes from a portion of the mandate that they have been given. In Arabic a part of their task has been specified as riqaba , which can be translated as either censorship or monitoring/supervision. It has been suggested that since prohibitions related to content are dealt with in the Lebanese Penal Code, the CAN's task is more closely related to the second understanding of riqaba .

Censorship

The Ministry of Information always maintains the "right" or at least the ability to control and censor press and media materials. Even though the press got foreign publication censorship abolished in 1967 and persuaded the Ministry of Information to withdraw censors from television stations in 1970, many changes and even the establishment of laws are seemingly no guarantee that they will be followed. The establishment of the CNA is a case in point—such an organization can one day be a promoter of accuracy in media and another day become its very antithesis.

In fact, on August 8, 2001, the CNA issued a document to the Council of Ministers relating to coverage of events. On August 9, Minister of Information Ghazi Aridi suggested an ominous warning to media saying that he would utilize the law to end "mistakes by media outlets, which threaten state security." Correspondingly, the An Nahar was charged with defaming the army, and lawsuits were brought against the author of the article, Raphi Madoyan, as well Joseph Nasr, the Editor-in-Chief of An Nahar . On August 16, journalist Antione Bassil, and on August 19, journalist Habib Younis, were arrested without warrants and interrogated without lawyers present. On April 8, 2002, journalist Saada Allao had to face the press court of Lebanon for writing articles in November 2001 that were critical of the judicial handling of a case concerning the disappearance of a little girl. Allao had quoted the little girl's mother relating how nothing had been done since she filed a complaint years earlier and had been told by the courts that the documents had been lost. For this article, Allao was on trial and facing three years of imprisonment or a fine of 20 million Lebanese pounds or about 13,500 euros. These are but a small example of how censorship continues to be utilized in Lebanon. As well, it can easily be imagined how self-censorship is practiced by journalists due to concerns for their own and their family's physical and psychological safety.

The problem remains that a country with a ruling on the books that deems it illegal to legitimately criticize the state or emissaries of the state, whether or not such criticism can lead to national instability or interstate instability, essentially retains the "right" for itself to arbitrarily prosecute journalists. In instances such as these, it is the state that defines what constitutes criticism and what the punishment should be given, which is antithetical to freedom of the press.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

Foreign media are typically welcome in Lebanon, but there are continuing instances of censorship and intimidation being propagated by the government. Other than case examples already presented, on August 9, 2001, Yehia Houjairi, cameraman of the Kuwaiti state television channel was arrested outside the courts of law for filming a demonstration against a recent raid on anti-Syrian circles called the CPL (Free Patriotic Movement). The chairman of the photographers union intervened on his behalf, and he was subsequently released. On the

The foreign press is welcome in Lebanon. However, it remains a significant concern that, even if somewhat limited, seemingly random acts of not only censorship, but violent censorship continue to occur.

News Agencies

The Lebanese domestic news agency is the National News Agency (NNA). It can be accessed on the Internet at http://www.nna-leb.gov.lb . It remains state-owned. There is also a single press association, the Lebanese Press Syndicate or Lebanese Press Order. It was founded in 1911 and has 18 members. It is available on the Internet at http://www.pressorder.org .

Currently, there are around 16 foreign bureaus in Lebanon, all of them essentially in Beirut. The bureaus include: Agence France-Presse (AFP), Agenzia Nazionale Stampa Associata (ANSA [Italy]), Allgemeiner Deutscher Nachrichtendienst (ADN [Germany]), Associated Press (AP [USA]), Kuwait News Agency (KUNA), Kyodo Tsushin (Japan), Middle East News Agency (MENA [Egypt]), Reuters (United Kingdom), Rossiiskoye Informatsionnoye Agentstvo Novosti (RIA Novosti [Russia]), United Press International (UPI [USA]), Xinhua (New China) News Agency (People's Republic of China), BTA (Bulgaria), Iraqi News Agency (INA [Iraq]), Jamahiriya News Agency (JANA [Libya]), Prensa Latina (Cuba), and Saudi Press Agency (SPA).

Broadcast Media

Television

Before the licensing requirement brought about by the Audiovisual Media Law in 1994, a multitude of stations dotted the electronic landscape. This has been curtailed. There are now seven television stations that can legally broadcast news information—the seventh just gained licensing in 2001. Télé-Liban began in 1959 but really came into its own in late 1977 as a merger between La Compagnie Libanaise de Télévision (CLT) and Télé-Orient and their subsidiaries of Advision and Télé-Management; in 2002 it faces significant financial hurdles and has suffered neglect in the hands of the government. The Lebanese Broadcasting Company International (LBCI), founded in 1985 by Christian businessmen, is the most universally watched in all regions. National Broadcasting Network (NBN) had a license initially granted before the station even existed; the major single stockholder is speaker of the Lebanese House, Nabih Berri. Murr TV (MTV), founded in 1992, and Future Television or Future TV (FTV), Al-Manar (Light-house) Television, and NTV are the remaining stations.

Another television station in operation that is not licensed to broadcast news is Télé-Lumiere, an educationally-based station owned by the Catholic Church.

Satellite television is accessible from Arabsat, Eutelsat, Intelsat, Polsat, as well as others. LBC-Sat, Future TV, Middle East Broadcasting Centre (MBC), Syrian TV, CNN, BBC, French TV5, French Arte, and French La Cinquieme are popular channels. Showtime and Orbit packages are available. Euronews and Al-Jazeera are available on Arabsat C-band.

Television broadcasting is said to be able to reach more than 97 percent of the Lebanese adult audience. All told, there are around 15 total stations (with five repeaters) broadcasting to 1.18 million sets.

Radio

Following the example of television, only a small number of radio stations have been allowed to broadcast news: Voice of Lebanon, Voice of the People, Radio Lebanese Liberty, Radio Lebanon (government owned), Voice of Tomorrow, and Voice of Light.

As well, local broadcasting is disallowed, and licenses are only provided for stations that can cover the entire country with their programming. The reasoning for this is to attempt to cause people to look beyond their local confines to the greater national area in order to engender feelings of national unity. A few small stations are avoiding closure, including a station broadcasting the Holy Quran, Sawt al-Mahabba , and Voice of the South.

Radio broadcasting reaches 85 percent of the Lebanese adult audience. However, while relatively ubiquitous in nature, it is a medium that is still trying to shake off images of wartime use for sending flash bulletins. If radio is utilized, it tends to be less for news than for music. Of those broadcasting news, the favorites seem to be Voice of Lebanon ( Sawt Libnan ) and Radio One (105.5 FM), which relays news neutrally interspersed with music.

Currently there are around 20 AM, 22 FM, and 4 shortwave stations in Lebanon broadcasting to around 2.85 million radios.

Internet

Lebanon's government has established its own site on the Internet. As well, there are a numerous other sites that are available originating from Lebanon. The country code is.lb and as of 2000, there were 22 Internet Service Providers (ISPs) in the country and 227,500 Internet users according to the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency.

Education & TRAINING

Journalists can gain their necessary baccalaureate education and further graduate education in the country from the Lebanese University, the American University of Beirut, or another acceptable institution.

Summary

The strength and weakness of Lebanon lies in its diversity. The people of Lebanon's commitment to locality has kept them from ever being entirely subjugated, but it has also kept them from ever being completely united. Hopefully, the Lebanese have had their fill of war. Connections are being established and reestablished. Buildings and lives are being built and rebuilt. The fact that Lebanon has always been relatively open to media and opinions, and the fact that media and opinions are more readily available today than ever before, is suggestive of great potential for the people and the country of Lebanon. They only have to take advantage of the opportunities.

Bibliography

All the World's Newspapers , 2002. Available from http://www.webwombat.com.au/intercom/newsprs/index.htm .

Atalpedia Online. Country Index , 2002. Available from http://www.atlapedia.com/online/country_index .

BBC News Country Profiles , 2002. Available from http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/world/middle_east/country_profiles .

Boyd, Douglas. Broadcasting in the Arab World: A Survey of the Electronic Media in the Middle East , 3rd ed. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press, 1999.

Central Intelligence Agency. The World Factbook 2001 , 2002. Available from http://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/ .

Centre for Media Freedom—Middle East and North Africa (CMF MENA). Lebanon Code of Ethics , 2002. Available from http://www.cmfmena.org/publications/Lebanon_Media_Environment.rtf .

——. The Media Environment in Lebanon: Public Access and Choice , 2002. Available from http://www.cmfmena.org/publications/Lebanon_Media_Environment.rtf .

Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). Middle East and North Africa 2001: Lebanon , 2002. Available from http://www.cpj.org/attacks01/mideast01/lebanon.html .

Freedom House. Freedom in the World: Lebanon , 2002. Available from http://www.freedomhouse.org/research/freeworld/2002/countryratings/lebanon.html .

International Press Institute. World Press Freedom Review , 2002. Available from http://www.freemedia.at/wpfr/world.html .

Kalawoun, Nasser M. The Struggle for Lebanon: A Modern History of Lebanese-Egyptian Relations . London: I.B. Tauris, 2000.

Kraidy, Marwan. "Transnational Television and Asymmetrical Interdependence in the Arab World: The Growing Influence of the Lebanese Satellite Broadcasters." Transnational Broadcasting Studies Journal (TBS) , Fall/Winter 2000, No. 5. Available from http://www.tbsjournal.com/Archives/Fall00/Kraidy.htm .

Lebanese Broadcasting Corporation International (LBC). Profile and History , 2002. Available from http://www.lbci.com.lb/history/index.htm .

Maher, Joanne, ed. Regional Surveys of the World: The Middle East and North Africa 2002 , 48th ed. London: Europa Publications, 2001.

Redmon, Clare, ed. Willings Press Guide 2002 , Vol. 2. Chesham Bucks, UK: Waymaker Ltd, 2002.

Reporters Sans Frontieres. Lebanon Annual Report 2002 . Available from http://www.rsf.fr .

——. Middle East Archives 2002 . Available from http://www.rsf.fr .

Russell, Malcom. The Middle East and South Asia 2001 , 35th ed. Harpers Ferry, WV: United Book Press, Inc., 2001.

Stat-USA International Trade Library: Country Background Notes , 2002. Available from http://www.statusa.gov .

Sullivan, Sarah. "Roundtable Examines Ethics, Media Freedom in Lebanon." Transnational Broadcasting Studies Journal (TBS) , Spring/Summer 2002, No. 8. Available from http://www.tbsjournal.com/beirut.html .

Sumner, Jeff, ed. Gale Directory of Publications and Broadcast Media, Vol. 5, 136th ed. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group, 2002.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics , 2002. Available from http://www.uis.unesco.org .

World Bank. Data and Statistics , 2002. Available from http://www.worldbank.org/data/countrydata/countrydata.html .

World Desk Reference , 2002. Available from http://www.travel.dk.com/wdr/ .

Zisser, Eyal. Lebanon: The Challenge of Independence . London: I.B. Tauris, 2000.

Clint B. Thomas Baldwin