Malaysia

Basic Data

| Official Country Name: | Malaysia |

| Region (Map name): | Southeast Asia |

| Population: | 22,229,040 |

| Language(s): | Bahasa Melayu, English, Chinese dialects, Tamil, Telugu |

| Literacy rate: | 83.5% |

| Area: | 329,750 sq km |

| GDP: | 89,659 (US$ millions) |

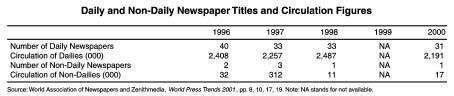

| Number of Daily Newspapers: | 31 |

| Total Circulation: | 2,191,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 130 |

| Number of Nondaily Newspapers: | 1 |

| Total Circulation: | 17,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 1 |

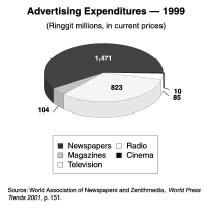

| Total Newspaper Ad Receipts: | 1,765 (Ringgit millions) |

| As % of All Ad Expenditures: | 58.60 |

| Number of Television Stations: | 27 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 10,800,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 485.9 |

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 525,000 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 23.6 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 92 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 10,900,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 490.3 |

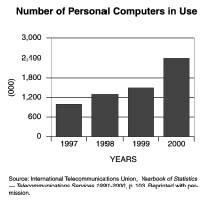

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 2,400,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 108.0 |

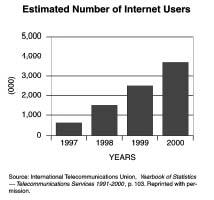

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 3,700,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 166.4 |

Background & General Characteristics

The southeast Asian country of Malaysia includes people from many other Asian and western countries and numerous ethnic groups. This diversity is reflected in its economy, politics, social systems, and culture. The first people to inhabit the Malaysia peninsula, the Malays, came down from South China around 2000 B.C. Around 600 A.D. Sri Vijaya headed a strong empire in southern Sumatra that dominated both sides of the Straits of Malacca. In the 1300s, Sri Vijjaya fell and the Majapahit Empire controlled Malaysia. The Muslims began to dominate the peninsula around 1400 when a fugitive slave from Singapore founded a principality at Malacca. This Muslim principality fell to Portugal in 1511, and in 1641, the Dutch took control from the Portuguese. The British East India Company entered the peninsula in 1786, and in 1819, the British established a settlement at Singapore. In 1784, British treaties protected some areas. In 1895 four states became the Federated Malay States. Thailand in 1909 ceded four northern states (Kedah, Kelantan, Trengganu, and Perlis) to the British, together with Johor in 1914, and this whole area became known as the Unfederated Malay States. In 1892, separate British control was extended to North Borneo, and in 1898 Sarawak became a separate British protectorate.

In December 1941, during World War II, the Japanese conquered Malaya and Borneo, and they held it throughout the war. After World War II, the British formed the Malayan Union that included the nine peninsular states along with Pinang and Malacca. In 1946, Singapore and the two Borneo protectorates became separate British protectorates. On February 1, 1948, the Federation of Malay succeeded the Malayan Union. In 1957, the Federation of Malay became an independent member of the British Commonwealth. In 1962, Malaya and Great Britain agreed to from the new state of Malaysia that would include Singapore, and the British Borneo territories of Sarawak, Brunei, and North Borneo, but Singapore voted not to join. However, for two years Singapore was part of the Federation of Malay states until 1965 when Singapore became independent. The "Federation" was dropped that same year, and Malaysia became the official name of the newly independent British colonies. Malaysia has a combined land area of 329, 760 square kilometers and is similar in size to New Mexico in the United States.

Nature of Audience

As of 2001, the multiracial population of peninsular Malaysia was estimated at 22,229,040. There are three main ethnic groups: the Ma-lays, called Bumiputera ("sons of the soil," 58 percent); Chinese (30 percent); the Indians (10 percent), and others (10 percent). More than 50 percent of Malaysians live in urban areas. Most of the Chinese live in urban and tin mining areas, while many Malays live in rural areas. The Chinese who live in urban areas are wealthier, and over the years spurts of ethnic violence have erupted between them and the Malays. The indigenous Orang Asli aborigines number about 50,000. The kampung forms the basic unit of Malay society, a tightly knit community consisting of kinship, marriage ties, and neighbor relationships which are regulated by traditional Malaysian values. In 1999, the four major languages were Malaya, Tamil (an Indian dialect), Chinese, and English.

The 1990s brought economic prosperity to Malaysia, which is rated as an upper middle-class country. The unemployment rate in the 1990s remained at nearly 4 percent. The literacy rate is 92 percent, and all Malaysians are required to attend school at least until age 15. Many Malaysians obtain degrees from local and foreign universities. With government loans some study in the United States, New Zealand, Australia, or the United Kingdom.

Written literature in Malaysia goes back to the sixteenth century and describes old Malaya society, for example, Hikayat Hang Tuah (Hang Tuah's Life Story) and Sejarah Melayum , a history of the Malaysian peninsula. The first newspaper in Malaysia, begun by the British in Panang in 1805, was the Prince of Wales Island Gazette .

The Malay government has continuously censored the press in response to political instability which characterized the peninsula for much of the twentieth century. In 1968, the Malaysia National News Agency, Bernama began operating. In 1984, the Printing and Publications Act enabled the Minister of Home Affairs to revoke any publications licensees deemed dangerous to the state. Malaysia is one of the most authoritarian and repressive countries regarding the press.

In the 1930s under British control, the country developed restrictive policies toward the press because it feared the spread of communism. In April 1930, the Malayan Communist Party was founded in Singapore. Mainly urban Chinese were members of the party, and as a result many were arrested. This group later became involved in the local labor movement. In 1990, the Communist Party in Malaysia collapsed.

Despite the threat of communism in the 1930s, the Malay vernacular press flourished in that decade. Between 1900 and 1918 of the 13 newspapers and periodicals started, Singapore published eight, Pennang published three, the federated states had two, and Kelantan had one. During the first two decades, the Singapore press produced Al-Iman (1906-1908) and Neracha (1911-1915), Islamic religious reform journals. The secular newspapers included Utusan Melaya (1907-1921) and Lembaga Melaya (1914-1931).

Early Publications & Two Early Editors

Utusan Melayu and Lembaga Melaya were modeled on the English press and sought to provide a more balanced view of the news. However, both newspapers reflected the views of the man who edited them, Mohd Eunos b. Abdullah, the so-called father of Malay journalism. Born in Singapore in 1876, the son of a prominent merchant from Sumatra, Abdullah was educated in the Malay School in Kampong Glam and graduated in English from the Raffles Institute in 1894. At thirty-one, after working several years as a master attendant in the ports of Singapore and Muar in Jahore, he took a job with the Free Press, Singapore's oldest newspaper. For the Free Press , he edited the Malay edition, and he witnessed a growing demand for a vernacular press. Abdullah with the help of William Makepeace, the owner of the Free Press founded the Utusan Melaya in 1907.

Published three times weekly in the vernacular Malaya language, the Utusan Melaya presented the cable and local news that appealed to an urban Singapore audience. This newspaper also commented on a wide range of public issues. Moreover, the paper was used as a language teaching medium in the schools.

In 1914, Abdullah also served as editor of the moderately progressive Lembaga Melayu , which mirrored the Malaya Trinbure . It did not publish editorials until 1929 but did publish accounts from the overseas wire service. This newspaper was the only daily published in Malaysia until it stopped publication in 1931.

In 1931, Onn b. Ja'afar founded the Warta Malaya , which became successful after the Lembaga Melayu folded. The Wasta Malaya became an important voice for the Malay readers because it shifted focus from Singapore to the Malaya peninsula. Warta Malaya influenced the startup of thirty-four other newspapers and periodicals between 1920 and 1930. Warta Malaya discussed wide-ranging issues that included controversial topics regarding non-Malay demands for increased rights and higher education and the development of the Malay economy for the Malays. It was also critical of the British occupation of Malaysia. Onn b. Ja'afar became an outspoken critic of colonial authority and the Malaya relationship with Great Britain.

By the mid 1930s there were over eighty-four periodicals published in Singapore and throughout the Malay Peninsula. During the years 1935 and 1936 there were twenty-five new Malaysia newspapers published in the Malay language. Increasing commercialization and professionalism in journalism, coupled with the affordable price, caused newspapers to flourish. By 1931, with over one-third of the males literate, these newspapers and magazines were widely popular, especially among schoolteachers and government workers. In addition to Warta Malaya (1931-1941), prominent Malaysian newspapers in circulation before World War II include Majils (1931-1941), Lembaga (1935-1941) and Utusan Malayu (1939-1941).

Political Unrest

In January 1941, Japanese troops invaded northern Malaysia, and the Japanese took over Sarawak in 1942. The British surrendered Singapore to the Japanese the same year, and the Japanese killed many Chinese residents, while others fled from the cities to the jungles. Many newspapers were suspended during the war. Then the British returned in 1945. The decade that followed included episodes of ethnic unrest and a resurgence of the Malaysia Communist Party in 1946, and in 1948, the British expanded their control over the media during what was called the Emergency, when communists tried to gain control over the government. During this twelve-year period, the government initiated aggressive media campaigns to control the terrorists. It. was not until 1960, however, that the communist insurgency was suppressed.

Inter-ethnic violence shook Malaysia in 1969 when the Malaysian Chinese Association withdrew from the government. Its removal destroyed the alliance of ethnic political parties. There were demonstrations, parades, and rumors of ethnic violence. At least 178 people died in rioting. The government declared a state of emergency, and Tn Abdul Razak (1922-1976), the prime minister, and the National Council temporally replaced the government.

On August 13, 1970, Malaysia proclaimed a national ideology, while the sultan served as the supreme ruler. The government proclaimed a five-point ideology, Rukunegara , for Malaysia. These principles included loyalty to the supreme ruler; the belief in God; respect for the Constitution, especially the special rights of Malays and the rule of law; and respectful behavior towards one another.

Social unrest, government censorship, and the 1967 Publications Act that was amended in 1984 put further restrictions on a free press in Malaysia. In 2002, Malaysian newspapers are primarily government controlled and censored. These newspapers contain about 60 percent of local and national news; the remaining space covers topics related to other parts of the world.

Newspapers & Their Circulation

The oldest English daily, New Straits Times (formerly the Straits Times ), founded in 1845 in Kuala Lumpur, is a business and shipping information paper with a circulation of 190,000. The Star , modeled on its Hong Kong cousin and on popular British tabloids, was founded in 1971 in Selangor. It has an average circulation of 192,059. The afternoon Malay Mail began circulation in Kuala Lumpur in 1896. It emphasizes lighter news and features and has a circulation of 75,000. Also, The Business Times was founded in Kuala Lumpur in 1976, by splitting the shipping and financial sections of the New Straits Times . It has a circulation of 15,000.

Post World War II Newspapers and Their Circulation

The Malay language newspapers after World War II attempted to carve out a separate Malay culture and identity. Of the five Malay language newspapers, the largest is the morning daily Berita Harian founded in 1957 in Kuala Lumpur with a circulation of 350,000. The Metro Ahad , also in Kuala Lumpur, has a daily circulation of 132,195. The Watan has a circulation of 80,000.

The four Tamil language newspapers are also published in Malaysia's capital, Kuala Lumpur. These newspapers are the Malaysia Nmban with a circulation of 45,000; the Tamil Nessan founded in 1924 with a daily circulation of 35,000 and a Sunday of 60,000; Tamil Osai with a daily circulation of 21,000 and a Sunday circulation of 40,000; and the Tamil Thinamani with a daily circulation of 18,000 and Sunday circulation of 39,000.

The seven Chinese language newspapers primarily cater to urban Malaysian Chinese. The China Press in Kuala Lumpur has a circulation of 206,000. The Chung Kuo Pao , also in Kuala Lumpur, has a circulation of 210,000. The Guang Ming , a daily in Selangor, has a circulation of 87,144. The Kwong Wah Yit Poh , founded in 1910 in Panang, has a circulation of 65,939 daily, and on Sunday 76,958. The Nanayang Siang Pau founded in 1923 in Selangor has a daily circulation of 183,801 and a Sunday edition circulation of 220,000. The Shin Min Daily News , established in Kuala Lumpur in 1966, is a daily morning paper with a circulation of 82,000. The Sin Chen Jit Poh , founded in 1929 in Petaling, Selangor, has a daily circulation of 227,067 and a Sunday circulation of 230,000.

There are four daily newspapers in English and Chinese in Sabah. The largest is the Sabah Times with a circulation of 30,000. It is followed by the Daily Express (25,520), Syarikat Sabah Times (25,000), and the Borneo Mail (14,000). The largest Chinese newspaper in Sabah is the Hwa Chiaw Jit Pao (circulation 28,000), Merdeka Daily News(6,948), Api Siang Pau (3,000), and Tawau Jih Pao (circulation not known).

There are five Chinese and three English newspapers in Sarawak. The Chinese newspaper with the largest circulation is the See Hua Daily News (80,000). The others are International Times (37,000), Malaysia Daily News (22,735), Miri Daily News (22,431), and the Berita Pe-tang Sarawak (12,000). The English newspaper in Sara-wak with the largest circulation is the Borneo Post with 60,000 subscribers. The others include The People's Mirror (24,990) and the Sarawak Tribune and Sunday Tribune (29,598).

On Peninsular Malaysia the Sunday papers in English include the New Sunday Times , established in Kuala Lumpur in 1932, with a circulation of 191,562. A competing Sunday paper in the English language founded in Kuala Lumpur in 1896 is the Sunday Mail with a circulation of 75,641. The Sunday Star in Selangor has a circulation of 232,790.

Sunday newspapers in the Malay language include Berita Minggu printed in Kuala Lumpur (421,127), the Mingguan Malaysia founded in 1964 in Petaling Jaya (493,523), and the Utuan Zaman also in Petaling Jaya and founded in 1964 (11,782).

The one Sunday paper in the Tamil language, the Makkal Osai , is printed in Kuala Lumpur and has a circulation of 28,000. As of 1999, there was no Chinese language Sunday paper in Malaysia.

The newspapers with the largest readerships in Malaysia in 2002 are The Star and The Sunday Star . First published in 1971, as a regional newspaper in George Town, Penang, The Star was the first tabloid newspaper published in Malaysia and the first English newspaper printed with the web offset process. It became Penang's premier newspaper in 1976, outselling The New Strait Times, a newspaper that was 139 years old. Also, Tunku Abdul Rahman retired in 1970 as Malaysia's first prime minister, and in 1976, he became chairman of the board. The same year, The Star went national by moving its headquarters from Penang to Kuala Lumpur. In 1981 it moved its headquarters to Petaling Jaya to accommodate a growing staff, as well as to improve with the latest technology in publishing. In 1995, The Star became the first Malaysian newspaper to launch an edition on the World Wide Web.

In June 2001 the daily circulation of The Star reached 279,647 and The Sunday Star reached 292,408. The New Strait Times had a circulation of 136,273, and New Sunday Times had 155,565. Malay Mail had a circulation of 34,206, and the Sunday Mail had one of 50,215. That same year 5,843 titles were published in Malaysia, amounting to over 29 million copies. There were 42 daily newspapers in 1996 compared to 44 in 1995. The average circulation of newspapers in 1996 was 3.3 million.

There are numerous magazines published each year in Malaysia, but many go out of print because of the difficulty in getting sufficient numbers of advertisers to support them. The top ten magazines in 2000 published in the Malay language are Al Islam , Anjung SeriBola Sepak, Dewan EkonomiDewan KosmikDewan Masyarakat, Dewan PelajarDewan SiswaIbu , and Jelita . The most popular English language magazine is Aliran Monthly , a reform movement magazine working towards establishing freedom, justice and solidarity for all Malaysians. Aliran Kesedaran Negara (ALIRAN), established in 1977, Malaysia's first multiethnic reform movement and the nation's oldest human rights group, publishes it.

Economic Framework

The economy in Malaysia recovered after a slow down in 1997. Prime Minister Mahathir blamed international speculators, especially U.S. billionaire George Soros, whom Mahathir believed was responsible for manipulating the currency market in Asia in 1997. In response to the declining economy Mahathir cut government spending by 18 percent and delayed huge development projects. By 2000, the Malaysian economy had improved, and the annual gross domestic product (GDP) had increased. The sixth Malaysia plan was successful because of continued governmental fiscal restraints and double-digit export growth. This plan encouraged trends toward privatization and increased industrialization.

While privatization is a goal in the business sector, a free press without government restrictions is hardly a priority. The government controls the presses and the publishing enterprises throughout Malaysia. There are strong political and economic ties between the government and the media. In 2002, for example, the Ministry of Finance owned 30 percent of the consortium that operates Mega TV. A subsidiary firm, Sri Utara, of the investment arm of the Malaysian Indian Congress, a political party in the coalition government, owns 5 percent of Mega TV.

Political Ownership of Media

The political parties and their investment companies control the major newspapers in Malaysia. The Utusan Melayu Group publishes three Malay language dailies and has strong ties to Prime Minister Mahathir's party. In addition, the Star is owned by the Malaysian Chinese Association, a party affiliated with the ruling coalition. Private interests aligned with the Malaysian Indian Congress control all the Tamil newspapers. The investment arm of Mahathir's party, the Fleet Investment Group, has controlling interest in TV 3 and the New Straits Times .

According to Aliran , the journal of social reform, these connections reveal the biases of the Malaysian media. During the 1995 general elections, the daily newspapers carried government advertisements in full but accepted only partial advertisements from oppositional parties. Some believe that newspaper owners do not allow new entrants into industry despite the fact that they may add to the public good. What the imprisoned Assistant Prime Minister Anwar called an "informed citizenry through a contest of ideas," is as of 2002 as elusive as ever in Malaysia.

Distribution Issues

Due to the various geographic features especially the straits that separate Peninsular Malaysia from Malaysia on the island of Borneo, there are problems connected to newspaper distribution, as well as the desire for some papers to go national or have sites on the Internet. Newspaper circulation reflects ethnic and geographic divisions. English papers are popular in large urban areas. The rural areas are conservative and read more Malay newspapers that catered to Muslims. Still there are few East Malaysian papers on the peninsula and still fewer peninsular papers can be found in circulation in East Malaysia. Singapore with a 90 percent Chinese population does not allow the circulation of papers from Malaysia, nor does Malaysia allow circulation of newspapers from Singapore.

The Star was the first Malaysian newspaper to be launched on the World Wide Web on June 23, 1995. The Star and Sunday Star also publish four magazines. Kuntum, an educational monthly in Bahasa Malaysia is for children ages six to twelve. Though not particularly popular, Shang Hai , is regarded as the most authoritative Chinese magazine in the country. Galaxie , is a light reading English entertainment magazine published fortnightly, claimed to be popular with teenagers and working adults. In addition, Flavours is a magazine devoted to good food and dining in Malaysia.

In 2002, in addition to the Star, quite a few papers had Internet sites. The English ones include New Straits Times, HarakahDaily.com , SarawakBansar.com , Malasiakini.com , and Bernama , the Malaysian National News Agency. Malay-language newspapers with Web sites are Dinmani.com in Tamil characters, , and Utusan Malaysia . Internet links to Malaysian Chinese newspapers are Kwong Wah Yit Poh and Nanyang SiangPau.

Newspaper Cost and Prices

The paper pulp prices have remained stable since the 1980s in Malaysia. In late 1980, the price for pulp was US$445 per ton; in 2002, the price was US$450 per ton. Malaysia purchases most of its newsprint from Canada. In the 1990s, Malaysia began recycling newsprint when Theen Seng Paper Manufacturing Sbn. Bhd started operating in Selangor darul Ehsan, Malaysia. This firm is the long established leading manufacturer of recycled paper in that country.

The average daily price for a newspaper in Malaysia has increased from 17 cents per copy in 1980 to 40 cents per copy in 2002. Sunday papers run about 60 cents for each edition.

Unions

The National Union of Journalists represents journalists in Malaysia. Labor strikes among journalists in Malaysia are rare, but disagreements with the government's strict policies have increased especially after the conviction of Anwar in 1998. In December 2001 about 40 journalists at the Sun staged demonstrations outside their office in Kuala Lumpur protesting the government's suspension of two editors. Altogether in 2002 there were nearly 7,000 people employed as journalists, photographers, and editors in the country.

Press Laws

In Malaysia two opposing positions define the newspapers. The Barisan National, the ruling coalition, contrasts directly with its opposition. Press accounts suggest the Barisan is moderate and its opposition is extreme. Barisan promotes harmony among ethnic groups while the opposition creates ethnic conflict. The press in Malaysia fluctuates between ideas about democracy as ideal and the elitism that is the fact in this classist society.

As of the early 2000s, the restrictions on the press laws in Malaysia have been associated with Mahathir Mohamad, who became prime minister in 1981 and in 1982 joined Malaysia's ruling party, the United Malay National Organization (UMNO). Dr. Mahathir Mohamad was responsible for the Printing Presses and Publications Act of 1984, which mandates all publications to have a license that can be revoked by the Minister for Home Affairs. There is no judicial review, and the ministers' decisions are final. These press laws constitute a holdover from British rule when the British successfully curtailed the spread of communism in Malaysia by censoring the press.

In 2002, the press restrictions are used by the UNMO to suppress any views that put the government or the Malaysian people in an unfavorable light. Most Malaysians read information that has been censored by the government. The UMNO and the Barisan National coalition are both allied in a national coalition that controls radio and television stations, as well as newspapers.

These coalitions put more restrictions on the press following the November 1997 election, when the Pan Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS) gained significantly against (UMNO). This election caused the UMNO-controlled government to ban the Harakak , the press-controlled newspaper that could only be sold to PAS party members. In 1998, this newspaper also increased in circulation following the prosecution of former Deputy Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim.

In 1987, three national newspapers closed under the Internal Security Act, the Printing Presses and Publications Act, and the Judicial Act. These newspapers, the English-language Star , the Chinese-language Sin Chew Jit Poh, and the Malay-language Waton , reported on the racial aspects of a political conflict between two government parties. In 1988, the government allowed these papers to reopen after they made substantial changes in their editorial management.

Although the government does not directly censor what is published in the print media, the ISA has affected the print media in Malaysia. In May 2001 the publisher of two major dailies controlled by Nanyang Press Sdn Bhd, Nanyang Siang Pau and China Press were sold to the Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA), a political party that is the second largest of the ruling coalition in Malaysia. The MCA gained control over these dailies, in addition to the seventeen other Chinese publications and magazines it owns. The Chinese Malaysian community opposed this action, but MCA purchased Nayang Press holdings after a rarely held government assembly meeting, Extraordinary General Meeting (EGM), approved the purchase. The effect of this purchase was to further curb the freedom of the Malaysian Press because the government directly controls all Malay and English presses.

The control shows up in various ways. In June 2001, the director of Utusan Melayu , Raja Ahmad Aminilah was forced to resign from the government controlled media group because he wrote a letter of appeal advocating that the jailed politician, Anwar Ibrahim, be allowed to choose his own medical treatment. Under the Sedition Act in May 2001, a party youth leader for Teluk Intan Branch, named Azman Majohan, was arrested by the police and held for ten days for uttering seditious words at a political rally in Taiping town. On May 2, 2001, the Hulu Klang state assemblyman Mohamed Azmin Ali was sentenced to jail for 18 months by a sessions court in Kuala Lumpur, after he was found guilty of providing false information in Datuk Seri Ibrahim's corruption trial that took place in March 1999.

On that same date, Anwar Ibrahim was not allowed to appeal his case in court to deny allegations (four on sodomy, and one corrupt practice) against him, although these charges were dropped by a High Court. Dr. Rais Yatin the de facto law minister said the charges were dropped because Anwar was already serving a fifteen year jail term. However, the defense team noted that Anwar was innocent, and there was no evidence to support the charges brought against him. Anwar was an advocate of freedom of the press in Malaysia and this caused the rift between him and Prime Minister Mahathir. It began in March 1996 at an Asian journalists' meeting when Anwar said that journalists should be a vehicle for "the contest of ideas and cultivate good taste." Shortly after that speech, Anwar told Time magazine that his views about a free press were in the minority: "My principle is an informed citizenry, is responsible citizenry, so there must be respect for freedom of the press."

In March 2001, the Home Affairs Ministry held up the distribution of Far Eastern Economic Review and Asia Week because of a photograph that made Prime Minister Mahathir look bad.

A libel award in July 2000 by Malaysia's highest court sent chills down the spines of timid journalists in Malaysia.. The high court upheld a 7 million ringgit (US$1.8 million) libel award to a Malaysian business tycoon, Vincent Tan. The court believed Tan had been damaged by four Malaysian industry magazine articles published in 1994. The journalist who was fined 2 million ringgit in the case, the 40-year veteran M. G. G. Pillai noted that during his whole career he had not earned enough money to pay the court costs or damages awarded against him. Pillai believed the decision by the high court reduces journalists to being public relations officers. This high court decision even prompted prominent international bodies to issue a report titled "Malaysia 2000: Justice in Jeopardy," which expressed deep concern about the judicial system in Malaysia.

Fallout from this high court decision caused several independent publications to have their annual permits rejected. The Home Ministry also put limits on the publication of the very popular Harakah , making it go from being bi-weekly to being bi-monthly. One columnist James Wong Wong concluded that all the acts that restrict freedom of the media, like the Internal Security Act, the Sedition Act, and the Official Secrets Act, have instilled fear among journalists and senior editors throughout Malaysia.

Censorship

All the media and press acts, the Printing Presses Acts, the Internal Security Act, and the Control and Import Acts give the Ministry of Information and the censors authority to ban imported and domestic material in Malaysia. In June 2001, the government confiscated more than 1,000 political books after conducting a raid by the Home Ministry Office in Jahor Bari. It was believed that the books confiscated by the government contained material alleged to be dangerous to racial harmony.

In another incident in May 2001 the Home Minister banned a book titled Pengakuan Paderi Melayu Kristankan Beribu-ribu Orang Melayu (Malay Priest Confesses to Having Converted Thousands of Malays to Christianity) because the book was believed to be detrimental to public order. Moreover, the Home Ministry in June 2001 held back three issues of the international news magazine Asia Week cover dates May 25 and June 8 contained criticism of the Malaysian Prime Minister, Dr. Mahathir.

There are few federal laws that restrict officials from providing journalists with information, unless the information has an effect on national security or the military. Government official can order the press not to talk with journalists or corespondents, if they deem the information sensitive.

State-Press Relations

Deputy Prime Minister Abdullah Ahrmad Badari, who took office following the sentencing of Anwar in 1999, is the Minister of Information. He has the responsibility for carrying out the communication activities through three departments: Department of Information, the Department of Broadcasting, and Film Negra Malaysia (National Film Unit).

Through the departments of Information, Broadcasting, and the National Film Unit, the Ministry of Information directs all the channels of news information in the country. This includes billboards and special television documentaries and films related to Malaysia, as well as codes and standards for radio and television.

By 2000 the relationship between journalists and the government had grown increasingly strained. Journalists and reporters have very little rights when it comes to criticizing the government. Evidence of this contentious relationship between the press and the government has caused several editors to be removed, as well as newspapers and magazines to be indefinitely suspended or completely shut down.

In January 2000, A. Kadir Jasin, the chief editor of New Straits Times Press Bhd lost his position after a disagreement with the government. Kadir published a series of articles that angered some of the top government officials and led to his removal.

Following the trial of Anwar Ibrahim in 1998, the government took a hard line and threatened that it would place more restrictions on the local and foreign press. In July 1998, the Deputy of Information Minister Suleiman Mohamad stated, "If the media indulge in activities that threaten political stability or national unity, we will come down hard regardless of whether they are locals or foreign."

Johan Jaafar, the editor of the leading Malay-language daily, the Utusan Malaysia , was forced under government pressure to resign in July 1998. The government disliked his paper's coverage of the operational problems regarding a new airport under construction. The stories were embarrassing to the UMNO party which is a major stockholder of the paper.

Magazines have also fallen under the government's scrutiny. In March 1999, the government notified the editor of Detich , a bi-monthly magazine, that its publishing license would not be renewed. Forced to suspend publication by the government, the Detich suffered major financial losses. The editor Ahmad Lutfi Othman told reporters after the government suspended the license: "We hope the ministry will be more rational in the future. We may have criticized the government occasionally but we never intended to break the law."

In August 2000 the government revoked the license of another magazine, this one edited by Ahmad Lutfi Othman. The decision to revoke the Wasilah license was politically motivated: Lutfi is a member of the Pan-Malaysian Islamic Party, one of the opposition parties to the UMNO.

Several individuals in January 2000 were arrested by the Malaysian government for alleged criticisms made toward the government. Some of those arrested were prominent party members, defense lawyers, and media professionals, for example, Zulkifi Suong, editor of Harakah , and Chia Lim Thye, the owner of 's printing company. Both Suong and Thye were charged with sedition relating to an article Harakah published in 1999 about the sacking of Anwar Ibrahim. In court, Thye and Suong pleaded not guilty to the charges, yet restrictions and limits were placed on the newspaper.

In April 2000, in order to smooth relations with the Malaysian media, the government announced plans to review the colonial era publishing laws. This pressure came from the press freedom community in Malaysia. The laws to muzzle the press and human rights groups began under British rule in 1948 and were tightened under Prime Minister Mahathir in 1984. Some 581 journalists signed a petition stating that opposition to these laws was growing, and they advocated that the government create a national press council to regulate the industry. Apparently, their petition fell on deaf ears because as of 2002, no council has been created to review the press laws.

The government has learned to pressure local media in various ways. Apparently upset with what the Malaysian press published from the international wire services (about 20 percent of Malaysia's news comes from that service), Prime Minister Mahathir announced that Moslem nations should set up their own international news agency to counter what he called the distorted views of the Islamic world. According to Mahathir, "If we don't have any faith in our own news agencies, we tend to publish what is distributed by the Western wire services." He continued: "As a result, we don't get at least an alternative view." He was also critical of the media's portrayal of terrorism as a solely a Muslim invention.

Attitude toward the Foreign Media

The government continues to have a very suspicious view of the foreign media. In August 1998, Information Minister Mohamad Rahmat announced the government's plans to put more restrictions on foreign journalists in the country. Foreign journalists in Malaysia are required to register with the Home Minisitry, and they have to obtain a work permit. They are also required to furnish the Ministry of Information with details about their professional and personal background and provide information about their employers before they can receive a government issued pass. While Rahanat did not announce what the new rules or restrictions would be for the foreign press, he made it clear that foreign journalists may not produce in "negative and bad news."

While no foreign journalist was jailed in the 1970s, this was not the case in the 1990s. A veteran Canadian journalist Murray Hiebert in September 1999 got a six weeks jail sentence for "scandalizing the court," a ruling from an antiquated piece of colonial legislation. His sentence originated from his 1997 article in Far Eastern Economic Review titled "See You in Court" that addressed the growing number of law suits being filed in Malaysia. The article centered on a suit brought by the wife of a distinguished judge who sued an International School for dropping her son from a debate team. Heibert noted that this case moved suspiciously quickly thorough the court system. The judge's wife sued Heibert because she believed his article undermined the Malaysian judiciary. The court held Heibert's passport and set his bail at US$66,000. Heibert accepted the six-weeks jail term because had he appealed he would have had to wait a longer period of time before the case was resolved in court. According to his lawyers, Heibert was the first foreign journalist in over fifty year to be jailed for contempt in Malaysia.

U.S. President Bill Clinton and Canadian Prime Minister Lloyd Foxworthy spoke out against Heibert's incarceration. Prime Minister Mahathir in an address to the UN General Assembly responded by going on the offensive, by talking about the double standards in the West regarding human rights issues: "I think American habits of arresting other citizens in other countries and bringing them back to trail in America is contrary to international law." Mahathir accused Canada of violating human rights in the treatment of its own indigenous groups. Later at an assembly of 1,400 Commonwealth jurists in Kuala Lumpur, he lashed out at the Western media, the United Nations, currency traders, and human rights groups who have a distorted view of right and wrong.

Prime Minister Mahathir frequently gives advice on how the media should behave. The 1999 World Press Freedom Review summed up Mahathir's style for handling foreign media. "Free reporting and fair comment on sensitive topics will most likely be greatly curtailed given the potential consequences. 'Advice' on how the media should behave emanates regularly from the Prime Minister's Office, setting a clear official tone." The review continued: "In his typical diatribes against the media, Mahathir calls for what he interprets as 'responsible' journalism and feels Western media should be held responsible for their 'misreporting' In practice, his view is that regardless of a story's accuracy or an overwhelming public interest, nothing should be published if it undermines the position of those in authority creates tension or unrest." The review concluded: "The prime minister claims that freedom is dangerous, and in less developed countries like Malaysia, the government has to curtail freedom of speech for the good of the people."

The government continues to restrict material it deems to be sensitive. For example, in February 1999, the Malaysian government banned its own agencies from subscribing to foreign publications found to be critical of Malaysia. Those publications banned from government agencies were Asiaweek , The Far Eastern Economic Review, and the International Herald Review . Sine the 1970s, the government has been extremely suspicious of these publications.

News Agencies

A statutory body that the Malaysian Parliament authorized in 1967 to be Malaysia's national news agency, Pertubohan Berita Nasional Malaysia (Bernama), began operations in 1968. Bernama has an appointed five-member supervisory council and a board made up of six representatives each from the newspapers and the federal government all subscribers of Bernama. They also have alternate members appointed by the government. Bernama offices are located in all the states of Malaysia. They are also located in Washington, D.C., London, New Delhi, Dhaka, and Melbourne. In 2000, Bernama was equipped with fully computerized technology. Its purpose is to provide news services, general and economic, to subscribers in Malaysia and Singapore. Moreover, most of the Malaysian newspapers are subscribers to Bernama, as well as the electronic media, including radio, television, and the Internet. Before 1998, nearly all Bernama news and information was in the form of still photographs and text, but that year the agency launched BERNAMA TV. Bernama also disseminates its news on the Internet.

Bernama was given the official right in June 1990 to distribute news throughout Malaysia, and it does so in Malay and in English. Bernama also has an exchange agreement with other agencies, including Antara (Indonesia), Organization of Asian News Agencies (OANA), Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), and the Middle East News Agency.

In late 1999, there were several foreign news bureaus with offices in Malaysia, all located in Kuala Lumpur: Agence France Presse (AFP), the U.S. Associated Press (AP), Italy's Inter Press Service (IPS), Press Trust of India, Thai News Agency, the U.S. United Press International (UPI), the U.K. Reuters, and the People's Republic of China.

Broadcast & ELECTRONIC News Media

Similar to the print media, the electronic news media also fall under government control. The Malaysian Parliament, approved by the Broadcasting Act in December 1987, gives the Minister of Information the authority to monitor and control all radio and television broadcasting. The minister can likewise revoke any license held by a private company deemed to have violated the provisions of this act.

The government also has strict codes that the radio and television media must follow. The May 2002 version of the Malaysian Advertising Code of Ethics for Television and Radio protects the television industry as well as the government's social pollicies. This code controls the content of commercials and advertisements. The code restricts programs or advertisements that promote an excessively materialistic lifestyle. Using sex to sell products is restricted. In addition, scenes involving models undressing are not allowed. Women have a strict dress code: they must be covered from the neckline to below the knees. Swimming trunks for men and women can only be shown in scenes involving sporting or athletic events. All scenes or shots must be filmed in Malaysia, and only 20 percent of foreign footage is allowed and then only after it is approved by the minister. Moreover, all musicals and songs must be produced in Malaysia.

Unacceptable products, services, and scenes include alcoholic beverages. Blue denims are restricted; however, certain jeans made of other materials can be advertised. Dramatizations that show the applications of products to certain parts of the body, such as the armpits, is restricted. Clothes with imported words or symbols are restricted because they may convey undesired messages. Other restrictions include scenes which suggest intimacy, disco scenes, feminine napkins, and kissing between adults.

Radio Malaysia broadcasts over six networks in various languages and dialects. Besides Radio Malaysia, Suara Islam (Voice of Islam) and Suara Malaysia (Voice of Malaysia) broadcast regularly in Peninsular Malaysia. Radio Television Malaysia broadcasts in Sabah and Sara-wak. There is also Rediffusion Cable Network Sbn Bhd and Time Highway Radio, both of which have offices in Kuala Lumpur and primarily serve East Malaysia.

Other television networks besides Radio Television Malaysia in Sabah and Sarawak are situated on Peninsular Malaysia. Television Malaysia, founded in 1963, controls programming from its main office in Kuala Lumpur. TV 3 (Sistem Televisyen Malaysia Bhd) is Malaysia's first private television station that began broadcasting in 1984. Meast Broadcast Network systems began operating when Malaysia's first satellite was launched in January 1996. Malaysia launched a second satellite in October of that year. Mega TV, which started broadcasting in 1995, has five foreign channels, and the government owns 40 percent of Mega TV. The commercial station, MetroVison began broadcasting in July 1995. It is 44 percent owned by Sendandang Sesuria Sbn Bhd and 56 percent owned by Metropolitan Media Sbn Bhd. In addition, as of 1996, when the government ended the ban on private satellite dish ownership, Malaysians can own dishes.

Malaysia's wealthiest media baron is Ananda Kirshnan, who owns the direct satellite and broadcast company, Astro. Kirshman is a powerful ally of the Malaysian government, and his financial ventures are directed to helping Prime Minister Mahathir achieved a fully developed Malaysia by 2020. Khazanah Nasional, a government-owned investment company, bought a 15 percent stake in Astro in 1996 for US$260 million. Regulators in the government have steadily supported Krishman's companies by providing him with essential licenses in telecommunications, satellites, and gambling. Kirshman, a graduate of Harvard University's Business School, wants to "provide Asian alternatives to the Western media offensive." In 1997, his studios were working overtime to produce shows that would be morally accepted to the conservative Asian audiences not only in Malaysia but also to the Philippines and Vietnam.

The growth of the Internet in Malaysia has created problems for the Malaysian government. One government project begun by Mahathir in the late 1990s was Cyberjava, the multi-media Super Corridor designed to attract high tech industry and serve as a community totally wired to the Internet similar to the Silicone Valley in California. It covers the same area as Singapore and is located on the tip of Peninsular Malaysia. In keeping with his promise Mahathir has pledged not to censor the Internet, and to promote Cyberjava, he has been forced to have a hands-off policy regarding the Internet. In 1998, the Malaysian government allowed Malaysia's first commercial non-government controlled online newspaper, MalaysiaKini to begin operations.

In March 2001, the government-operated press instituted a campaign to undermine the credibility of Malay-siakini , the only non-government controlled online newspaper that began in 1999. The most credible media voice in Malaysia, this paper took advantage of Mahathir's promise not to ever censor the Internet. Mahathir, however, became upset with Malaysiakin i when the Far Eastern Economic Review reported that it received funding from George Soros' Open Society Institute. The prime minister was quoted to have said that loyal Malaysians should stop reading Malaysiakini because of the possible link to Soros. Mahathir has often attacked Soros in his speeches probably because Soros is a Jew, and Mahathir is a Muslim. Steven Gan, the editor of Malaysiakini , refuted the charges and even produced financial records that showed that the paper had never received any money from Soros. Gan received the International Pioneer Press Freedom Award in 2000.

In the early 2000s, the debate about trying to censor the Internet in Malaysia continues. In March 2002 both the public and Parliament are split on the issue; half want to see tighter controls and censorship, and the remaining half wants the Printing Press laws to be discontinued and the Internet to be free from government censorship.

Education & TRAINING

Some of the first courses for journalists in Malaysia were conducted by the South East Asia Press Center (SEAPC), formed in 1966 and supported by the Ministry of Information, local newspapers, and the Press Foundation of Asia. Its purpose was to provide something on the order of inservice education for people already employed as journalists in the country. Graduated courses in journalism are offered by the Universiti Sains Malaysia. Programs in journalism began in 1971 in the School of Humanities at that institution. In 2000, one of the major criticisms among journalists' in academia is the lack of enivronmental journalism in the Malaysian curriculum.

Courses in mass communications were first offered at Institut Teknololji Mara (ITM). Mostly the Malaysian government finances this institution and students must be bumiputras in order to attend. The school is situated in the suburbs of Kuala Lumpur. Universsiti Kebagsaan Malaysia (the National University of Malaysia) also has courses and offers degrees in mass communication and journalism. The school is located in Bangi, south of the

The headquarters of the Asian Institute for Broadcasting, affiliated with the Ministry of Information is the Institut Penyiarn Tun Abdul Razak (IPTAR) at Angkaspuri. There are courses at that institution through the Asian Institute for Broadcasting (AIBD). This institution receives partial support from UNESCO and the Malaysian government.

The National Union of Journalists (NUJ) is the major journalistic association in Malaysia, and it is affiliated with the Confederation of ASEAN Journalists. The other association is the Newspaper Publishers Association.

Steven Gang, the editor of MaylasiaKini received the International Pioneer Press Freedom Award in 2000 for his efforts at keeping his online newspaper free from government intrusion. In May 2001, on "World Press Freedom Day," the Committee to Protect Journalists meeting in New York City put Mahathir Mahamad on the "Top Ten Enemies of the Press" list.

Summary

While Malaysia has kept up with the rest of the world in technology and a prosperous economy, a truly free press in 2002 does not exist in this Southeast Asian country. Little has changed. The government still views the media as a means for promoting the government. It believes the press should not be sensational but should be a watchdog for society.

Journalists in Malaysia have to contend with many obstacles that journalists who live in other countries do not. The local and foreign journalists in Malaysia have to contend with various press laws and publications acts, as well as libel suits. It seems little change can be expected in the years to come so long as the government associates gains with a press controlled by the authorities.

Significant Dates

- 1984: The Printing Presses and Publications Act is revised.

- 1994: The Communist Party is no longer active in Malaysia.

- 1998: Deputy Prime Minister Anwar is charged with corruption and jailed.

- 1998: MaylasiasKini , the first on-line commercial newspaper, is established.

- 1998: Murray Heibert is the first foreign journalist jailed in Malaysia in over fifty years.

- 1998: A. Kadir Jasin, editor of New Straits Times, is forced by authorities to resign.

- 1998: Authorities cancel the publication of two magazines, Esklusif and Wasilah .

- 1999: The National Union of Journalists (NUJ) urges the government to provide a more favorable environment for the press industry.

- 1999: Five hundred and eighty-one journalists call for an appeal of Printing Presses and Publications Act.

- 2001: The debate over the licensing of publications escalates.

Bibliography

Asher, R. E., ed. The Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics, vol. 5. New York: Pergamon Press, 1994.

Barr, Cameron W. "Combative Leader Challenges Both His People and Foreign Press," Christian Science Monitor, vol. 90, issue 212 (28 September 1998): 8.

"Detention Without Trial: Internal Security Act, ISA," Malaysian Civil and Political Rights , 2nd Quarter 2001 (April-July 2001), Suram, Selangor, Malaysia.

The Europa World Year Book , vol. II. London: Europa Publications Limited, 1999.

"Foreign Labor Trends, Malaysia, 1994-1995," U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of International Labor Affairs, prepared by the American Embassy, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1995.

Gullick, John. Malaysia: Economic Expansion and National Unity. Boulder, Col.: Westview Press, 1981.

Ingram, Derek. "Commonwealth Press Union," Round Table , vol. 349, issue 1 (January 1999): 28.

Kurian, George Thomas, ed. World Press Encyclopedia. New York: Facts on File, Inc., 1982.

Loo, Eric. "Media Tightly Prescribed," Neiman Reports , vol. 50, issue 3 (Fall 1996): 79.

"Mahathir's Dividend," The Economist , vol. 330 (12 March 1994).

"Malaysia's Rough Justice," The Economist , vol. 348 (28 August 1998).

Martin, Stella, and Denis Walls. In Malaysia. London: Brandt Publications, 1986.

Murphy, Dan. "Malaysia's Strike on Freedoms," Christian Science Monitor , vol. 93, issue 74 (13 March 2001):3.

Neto Anil. "Libel Award Chill Malaysia's Journalists," Asia Times , July 15, 2000. Available at http://www.atimes.comINTERNET .

Osman, Mohd Taib. Malaysian World-View. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1985.

"Publish and be Chastised," The Economist , vol. 358 (3 March 2001).

Roff, William R. The Origins of Malay Nationalism. New Haven, CN.: Yale University Press, 1967.

Ross-Larson, Bruce, ed. Malaysia 2001: A Preliminary Inquiry. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Syed Kechik Foundation, 1978.

"The Shaming of Malaysia," The Economist , vol. 349 (7 November 1998).

Sumner, Jeff, ed. Gale Directory of Publications and Broadcast Media , 136th ed., vol. 5. Farmington Hills, MI.: Gale, 2002.

Van Wolferen, Karel, "The Limits of Mass Media," NIRA Review (Winter 1995).

Lloyd Johnson

Iwant to publish a newspaper (Weekly)in malaysia for urdu communitee.

1. what are the official requirements for re-print in Malaysia a bilingual newspaper for minorities which is published in Hong Kong.

Expecting soonest reply in detail,thanks in advance.

Regards,

S.J.Raghbi

(Hong Kong)

I am searching for the english version of the ministry of education's web site address, when i searched in google it is showing the Malay language , so I can't read , pls if you could find email me back,

thanks

ravichandran.

Nice to meet you.

May i know about where do you get the above breakdown list of Malaysia Press, Media, TV, Radio because i would like to get the latest result for my research stuff.

thank you.

best regards,

su ping

please help me...

faster thank you..

The name of the first newspaper was Government Gazette. It was later changed to Prince of Wales Island Gazette. It became popular by that name. The first issue was published on March 1, 1806. The hard copy of this first newspaper can be viewed at the British Library Newspaper collection at Colindale, United Kingdom. Unfortunately, the first three issues were missing. In Malaysia, this newspaper is available on microfilm and can be viewed at University Malaya and Universiti Sains Malaysia libraries.

The newspaper was published by A.B.Bone (full name Andrew Burchett Bone). He was a printer and publisher of newspaper in Madras before coming to Penang. He published two newspapers while in Madras. Apart from publishing the Government Gazette, Bone was also an auctioneer. He died in 1815, a poor man. His newspaper was published by some one else until it was folded in 1827.