Moldova

Basic Data

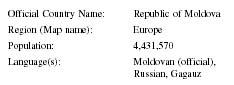

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Moldova |

| Region (Map name): | Europe |

| Population: | 4,431,570 |

| Language(s): | Moldovan (official), Russian, Gagauz |

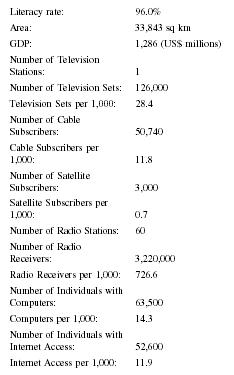

| Literacy rate: | 96.0% |

| Area: | 33,843 sq km |

| GDP: | 1,286 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Television Stations: | 1 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 126,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 28.4 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 50,740 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 11.8 |

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 3,000 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 0.7 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 60 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 3,220,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 726.6 |

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 63,500 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 14.3 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 52,600 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 11.9 |

Background & General Characteristics

In 2002, 180 newspapers and magazines were published in the Republic of Moldova. Printed media, as well as TV and radio programs appear in Romanian, Russian, Gagauzi, Bulgarian, Ukrainian, and Yiddish languages. Although the Constitution defines Moldavian as an official language, it is a regular practice among many people, including the intellectual elite and officials to refer to Moldavian as Romanian to emphasize once common history and culture of Moldova and Romania.

The Moldavian population is, in general, well educated and overall is interested in mass media. According to the census taken in 1989, 96.4 percent of the adult population were literate. About 70 percent of them had secondary or higher education. Moldova has a mandatory 9-grade school education for young people.

Press History

The history of the Moldavian press begins in 1790 when the first official periodical Curier de Moldavie (Moldavian Herald), in the French language, was initiated in the city of Yassy near the Russian Army Headquarters. The periodical was dislocated to the territory of the Moldavian Knighthood after the Russo-Turkish war of 1787-1791. In 1829, famous writer Georgi Asaki introduced to the public the first newspaper ( Albina Romanesca, or Romanian Bee) in the native Romanian language. It was published in Yassy every two days on four pages. In July 1854, Moldova, which was then called Bessarabia and was a province in the Russian Empire, commenced the publication of the official newspaper Bessarabskie Oblastnye Vedomosti (Bessarabian Official Reports) under the auspices of the local governor authorities. The first magazine Kishinevskie Eparkhi al'nye Vedomosti (Official Reports of Kishineu Parish) which appeared in 1867, both in Russian and Romanian languages had religious orientations. In 1917, it changed its name to Golos Pravoslavnoi Bessarabskoi Tserkvi (Voice of Bessarabian Orthodox Church).

The history of private press begins with the Bessarabski Vestnik (Bessarabian Herald) which was published on a weekly basis in the city of Chisinau in 1889 by Elizabeth Sokolova, the wife of the local high official. Along with the official reports, it placed articles reflecting the social, political, and economic life of the province; literary essays; and humor stories. The weekly leaned toward democratic circles of the Bessarabian society.

In 1854-1899, Bessarabia had 28 printed publications, including 9 newspapers, 2 magazines, 14 publications by various institutions, and 3 address-calendars. Their number had increased dramatically to 254 by the beginning of the twentieth century. It included both official and non-official newspapers and magazines such as Literary Almanac , Bessarabian AgricultureWine and Gardening, Wine and Winery , among them. Sixteen publications were in Romanian.

In 1918-1940, the larger western part of Bessarabia became occupied by Romania, while the smaller one attained a status of Moldavian Autonomous Socialist Republic within the Soviet Ukraine. The Moldavian press in Romania developed under the great influence of local nationalism and Romanian culture, while in Socialist Moldavia (until 1991), all state-owned media promoted the ideas and practices of the Communist party and its ideology. No independent mass media existed in the Socialist Moldavia. Though mass media achieved significant accomplishments during the Soviet times, such as the publication of ninety printed editions in various ethnic languages, and the development of the huge radio and TV broadcasting networks, to name a few, they had a strict state and party censorship.

Mass Media under Democracy

In 1991, Moldova was proclaimed a sovereign state. As a democratic, free market-oriented country, Moldova eliminated the state and Communist party monopoly and the censorship in media production: state publishing houses, radio stations, and printed media became privatized. The emergence of independent media, news agencies, TV channels, and radio stations became a reality. Religious press grew fast. Demand, supply, and competition started ruling the mass media market. However, the first results were not quite encouraging for many media employees. The process of privatization did not proceed in a just, fair way for them, because journalists, reporters, and other media professionals were deprived of the right to purchase any publishing, broadcasting, and photographic facilities. Many media that were purchased, furthermore, could not find financial resources and consequently failed. In the mid-1990s, the government began to nationalize some of them. As a result, 50 percent of all printed and electronic media returned to state control. This, of course, did not promote the freedom of press in the country. The journalists faced a dilemma: to fight for a real independence, including a financial one, or serve the interests of the government which guaranteed salary and means for existence in exchange for surrendering certain freedoms. Due to the economic difficulties, many journalists chose a third way: to serve the political interests of the parties that mushroomed (over fifty at the beginning of 1990s) since the sovereignty was proclaimed. This decision led them, to a great extent, to lose their professionalism and objectivity. The political parties' press dominated the market in the first half of the 1990s. A decade later, when the citizenry realized that the press media was not objective, the number of parties and party press significantly dwindled. Though 40 percent of the press still belonged to the parties in 2002, their circulation did not reach the circulation of the independent press.

Most Popular Newspapers and Magazines

Two newspapers stand out on the media scene; Moldova Suverena (Sovereign Moldova), with a circulation of 7,000 copies, in Romanian, and Nezavisimaya Moldova (Independent Moldova), with a circulation of 10,500 copies in Russian. Both support the party in power and the political forces associated with it. This was borne out in 2001 parliamentary elections, when they both upheld the political alliance headed by the Prime Minister Dmitry Bragish.

The nationalistic resurgence movements of Moldova promote their agenda through a variety of newspapers. One of them, Literature si Arta (Literature and Art, with 18,200 copies), a weekly published in Romanian, belongs to the Union of Writers of Moldova. Traditionally, it leans toward the right and disseminates the national-patriotic sentiments. In 2001 parliamentary elections, it backed up the Party of Democratic Forces since its editor-in-chief Nikolai Dabizha could be found among the candidates of this party.

The right spectrum of the Moldavian press is represented by the daily Flux, which is considered the most influential newspaper in the Romanian language (36,000 copies). It expresses the outlook of the pro-Romanian circles in the country under the leadership of Yuri Poshka, the Chairperson of Christian-Democratic People Party. The independent Jurnal de Chisinau at 11,000 copies, and Tara (Country) at 7,500 copies, both in Romanian, and Novoe Vremya (New Time) at 10,000 copies, published in Russian by the Democratic Party, can also be numbered among this spectrum.

In 1995, the Party of Resurgence and Accord (PRA) headed by the ex-President Mircea Snegur launched the Russian-language newspaper Moldavskie Vedomosti (Moldavian Official Reports), at 6,000 copies. It gradually lost its party affiliation, though still remains between the right and the center media in the political arena. The former official newspaper, Luceafurul (Morning Star), with a circulation of 10,000 copies, claims to be independent from the PRA since 2001, however, it still adheres to a great extent to the politics of this party.

The Romanian-language weekly Saptamina (Week), 17,400 copies, represents the political views of the centrist movements and adheres to the party in power. It was founded in 1992.

Kishinevskie Novosti (Chisinau News), 8,400 copies, adheres to the left. Since its foundation in 1991, it remains one of three most popular newspapers published in Russian. It successfully combines information with advertisements, allocating balanced space to classified ads and to information on serious and light aspects of life in the capital.

The Communist Party of Moldova disseminates 25,000 copies of the newspaper Communist , both in Romanian and Russian, which was published once a week until 2001 and twice a week since then. The publication enjoys popularity predominantly among the Party supporters and elderly generation. Over time, it has become less orthodox in expressing Communist views and ideology.

The extreme political orientation of many national newspapers makes it difficult for the readers to form an objective opinion on the events in the country, since very few individuals, due to the present severe financial constraints, can afford to buy a diverse array of publications. The population is equally as swayed in the remote rural areas where they predominantly read press materials, listen to radio programs, and watch TV shows produced by local companies.

There are also periodicals for various sub-groups of the population. Some of them target children and teenagers, Noi (We), in Romanian; Drug (Friend), in Russian and a private magazine Welcome Moldova , in English; or youth Tineretul Moldovei (Young Moldavian), in Romanian and Otechestvo (Fatherland), in Russian; and others are designed for women. Most of the press comes from Romania, Russia, and Ukraine. There are also a variety of periodicals devoted to sports, hobbies, and recreation. Among the sports periodicals are Rest with Soccer , Sport Plus, and Sport-Curier .

On the territory of self-proclaimed Pri-Dnestr Moldavian Republic, the mass media work under strict state censorship. Most of them keep to pro-government orientation. Pridnestrovskaya Pravda (Pri-Dnestr Truth) and Pridnestrovie (Pri-Dnestr) are the most known in that area.

The democratic processes in Moldova created opportunities for the development of new information agencies. The monopolist of the one state agency, ATEM, dissolved. Among more than a dozen new agencies, there is the government agency Moldpres (1940), the Chisinau municipal council agency Info-prim (1998), and the independent agencies Basa-pres (1992), NICA-pres (1993), Interlic (1995), AP "FLUX" (1995), and "DECA"-pres (1996).

Press Laws

Freedom of expression, speech, and access to information are basic rights guaranteed by the Constitution of Moldova, which was adopted in 1994. According to Article 32, every citizen is guaranteed "the freedom of thought, opinion, and their public expression in words, paintings, or by other means." Article 34 guarantees the right to have access to any information concerning governance and the functioning of state bodies. Article 5 forbids censorship.

The Constitution's articles of the press are supported by three major laws, the Law on Press (1994), the Law on TV and Radio (1995), and the Law on Access to Information (2000). The Law on TV and Radio is considered by legal experts a major step forward for it envisions the transformation of state broadcasting in public and private sectors. It also stipulates the procedures for the establishment of independent broadcasting companies.

The Law on Press guarantees political pluralism (Article 1, paragraph 1). Any legal organization or any citizen of the country over eighteen years of age has the right to open a news agency or launch a periodical (Article 5, paragraph 1). All media must be registered in the Ministry of Justice. The state pledges to defend the honor and dignity of journalists, their life, and property (Article 20, paragraph 3). The media must not inflict harm upon the honor and dignity of any citizen or to his/her private life, his/her right to have an opinion; to the national security, territorial integrity, public calm and law. They are not to disclose confidential information.

The Criminal Code of the Republic of Moldova, Article 7, guarantees citizens the right to file law suits against those media which publish false information about them. The Code stipulates significant fines (up to 200 minimum monthly salaries) for publishing false information in the press. Defamation in any print form can be punished by up to three years imprisonment or up to 50 minimum monthly salaries.

The Coordination Council on TV and Radio Broadcasting grants and revokes licenses for TV broadcasting and allocates radio frequencies on a competitive bid basis, sponsored by the Ministry of Transport and Communications.

The professional journalist organizations consider some articles of the laws inaccurate, incomplete, or contradictory, which interferes with the free functioning of the press. For example, they expressed concern about Article 7, paragraph 4 of the Law on Press, which does not specify in which cases the court has the right to terminate a license. It does not specify the words "misuse of the media" which can have multiple interpretations. The concerns were also expressed by journalists about the possibility of abuse of Article 7, paragraph 1 of the Legal Code for moral damage in cases of criticizing the activities of government officials.

State-Press Relations

Although the existing laws of the Republic of Moldova guarantee mass media the freedom of expression, from time to time many of them come across serious problems. The ban on censorship does not imply its total elimination. An unofficial, covert censorship often takes its place in many mass media. This perspective is supported by the survey of journalists conducted by the Center for the Support of Freedom of Expression and Access to Information in November, 2001. The presence of direct or indirect censorship was acknowledged by 95.6 percent of journalists.

The party and political censorship grossly prevail. The government efficiently uses the imperfect laws and economic leverages in exercising its pressure on media. The laws are often used to defend not the freedom of expression and speech, but the reputation of corrupt individuals. About 800 lawsuits were filed by government officials against journalists since 1995. There are grave obstacles in implementing the Law on Access to Information. Since its adoption, not a single lawsuit was filed against any state official for hiding any publicly significant information. The press services of the government and governmental bodies appear to serve as filters, not suppliers, of information.

The licensing of electronic mass media serves as another powerful tool of intrusion and direct control of the state over the content of the press materials. The Coordination Council on Radio and TV Broadcasting includes only the representatives of the power; lay people are not among them.

The critical coverage of the government and governmental bodies can be found mainly in the opposition party media. Shutting down the Commersant Moldovi (Moldavian Salesman) in 2001 serves as an outstanding example of persecution of media for critical coverage of some events. The newspaper was accused of promoting separatism of the country when it published interviews with the leaders of the unrecognized Pre-Dnestr Moldavian Republic, which fought for secession from Moldova.

The state and independent mass media find themselves in unequal economic conditions. The low quality of life of the population (in 2002, 75 percent of the population lived below the poverty line) deprived independent mass media of their major financial support from their readers. The newspapers and magazines that had circulation of 200,000 and more during the Soviet times dropped their circulation to between 10 and 15 thousand copies. The high cost of paper imported by Moldova, constantly increasing tariffs for photographic services, and taxes which are as high as in other businesses put many publications on the brink of bankruptcy. In these conditions, the government uses sales tax as one of the forms of manipulation with mass media. The introduction or elimination of the tax depends upon every new government. Growing tariffs on subscription and delivery of media worsen the situation.

Foreign capital's ownership of stock in Moldavian print-media companies is restricted by law to no more than 49 percent; for electronic media the percentage cap is 85 percent.

The deepening economic crisis in the country does not allow private businesses to place their commercial advertisements in media to increase their income. Additional taxation of advertisement does not encourage media hunts for potential customers. Many companies spend tiny amounts of money on advertising.

The journalists encounter many problems because they do not have a trade union of their own. They are members of the Union of the Workers of Culture, a part of the independent trade union of Moldova Solidaritatea (Solidarity), which does not effectively defend its members. As a result, in 2002, a group of concerned journalists created a steering committee to establish a professional union of their own.

The journalists of Moldova can join various creative organizations, such as the Union of Journalists of Moldova. The newly created League of Journalists of Moldova acts as an alternative association to support and defend their rights and to promote professionalism. The journalists exercise their rights and actualize interests and needs through other alliances, such as the Association of Electronic Press or APEL, the Committee for the Freedom of Press in Moldova, Independent Journalism Center, and Center for the Support of Freedom of Expression and Access to Information.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

The Republic of Moldova is a democratic society. In 2002, over 70 foreign publishing houses, information agencies, radio and TV companies received accreditation with ITAR-TASS, RIA Novosti, Radio Free Europe, BBC, Editing-Frans, Deutsche Press, ARD, International Media Corporation, Journalism 2, and PRO-TV among them. The accreditation of foreign journalists is carried out by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in accordance with the Procedures for Accreditation and Activity of Foreign Journalists, approved by the government in 1995.

The Western press is distributed mainly by subscription. It is not available for retail sale. One can purchase Western newspapers and magazines only in the governmental institutions, elite hotels, and restaurants. Private companies deliver The Wall Street Journal Europe , The Guardian Europe, Financial TimesBildLe Monde , Newsweek , and others.

The press from Russia prevails in retail sale due to high demand. Three Russian publications Argumenty I Fakty (Arguments and Facts), Komsomol'skaya Pravda (Komsomol Truth), and Trud (Labor) have supplements with an overview of major political, economic, and cultural events in the Republic of Moldova.

Broadcast Media

While prior to 1991 Moldova had only one state-run TV company, in 2002 there were 39 non-cable TV studios and 47 cable TV studios. Only four of them belong to the state. These stations are, Teleradio-Moldova, Gagauzia, Euro TV-Chisinau, TV-Balti. The most popular private TV studios are NIT, ORT Moldova, PRO-TV, TV6-Balti, and TV26-Chisinau. The biggest cable TV studio, SunTV, is a joint venture of USA and Moldova with 70 percent of the stock belonging to the American side. The cable TV network develops rapidly not only in the capital Chisinau, but all over the Republic, with Balti-6 and TV-SAD in Beltsy; Centru-TV, SATELITTV, and Alternative-TV in Chisinau; and Inter-TV in Faleshty. Practically every district, capital, and big city has cable TV. Though censorship is outlawed in radio and TV, the hidden censorship influences the work of some companies. It relates to the greatest extent to the state company Teleradio Moldova. Its chair is elected by the Parliament and often exercises subtle pressure on the journalists in the interests of the Parliament majority and blocks the opposition from access to the listeners. In one case, the head of the company repeatedly dismissed two journalists. Yet in each case they appealed in court and were reinstated.

In March and April, 2002, the bigger part of the journalist core of the Teleradio-Moldova company went on "passive" strike to protest against the subtle censorship. The journalists also demanded the adoption of the Law on Public TV and to turn the state TV company into a public one to reflect the interests of all layers of Moldavian society.

The international TV companies must get a license to operate in the country. Among those that were granted licenses are Romanian Public Television TVR-1 and TV company TV-5 (Francofonia, a Belgium-France Switzerland conglomerate). Broadcasting of Russian TV channels is regulated by the Agreement, signed in 1997 by the governments of the Moldavian Republic and the Russian Federation. Some other international channels are aired by local companies on the basis of bilateral agreements, which are registered by the Coordination Council on TV, and Radio Broadcasting. Russian ORT, RTR, NTV, RentTV, and Romanian PRO TV enjoy the most popularity among the Moldavian audience.

As Moldova received independence, the number of radio stations significantly grew in the country. There were 28 stations in 2002, with 21 of them in the capital city of Chisinau. Radio-Polidisc (Chisinau), Radio-Nova (Chisinau), HIT-EM (Chisinau), BlueStar (Beltsy), Radio-Sanatate (Edintsy), and the State Radio Station are known to be the most popular.

The following foreign radio stations acquired licenses to broadcast in the Republic: France-International, Free Europe, and the BBC. Radio stations of Russia and Romania are very popular too.

The Coordination Council on TV and Radio Broadcasting issues licenses. The Council also controls the implementation of laws by TV and radio companies. Its nine members represent each branch of power on an equal basis. The Council is re-elected every five years and the chair is elected by its members.

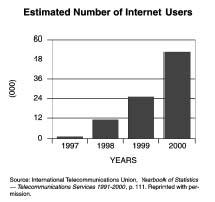

In the late 1990s, the country witnessed the growth of electronic online press. Reporter.md, MoldNet, MoldovaOnline, Infomarket.md, Integrare Europeana,

Education & TRAINING

Until 2001, Moldova State University had been the only educational institution that prepared the journalist cadres for the country in both Romanian and Russian languages. Between 1966 and 2002, 1,500 journalists graduated from the University. In 2001, departments of journalism were launched in two private institutions, the International Independent University and Slavic University.

Bibliography

Corlat, S. Editii Electronice in Format HTML. Chisinau: Centrul Editorial al FJSC a USM, Moldova, 2002.

Coval, D. Jurnalism de Investigatie . Chisinau: Centrul Editorial al FJSC a USM, 2001.

——. Problematica Presei Scrise . Chisinau: Centrul Editorial al FJSC a USM, 1997.

Dreptul Tau: Accessul la Informatie . Chisinau: Universul, 2001.

King, Ch. The Moldovans : Romania, Russia, and the politics of culture . Stanford, Calif.: Hoover Institution Press, 2000.

Koval, D. Pervaya Chastnya Gazeta v Bessarabii v XX Veke . Chisinau: Centrul Editorial al FJSC a USM, 1996.

Marin, K. Comunicare Institutionala . Chisinau: Centrul Editorial al FJSC a USM, 1998.

MASS-MEDIA in Societatile in Transitie: Realitati si Perspective . Chisinau: Central Editoria al FJSC a USM, 2001.

Moraru, V. Mass Media Versus Politica . Chisinau: Centrul editorial al FJSC a USM, 2001.

Grigory Dmitriyev

Viktor Kostetsky