Myanmar

Basic Data

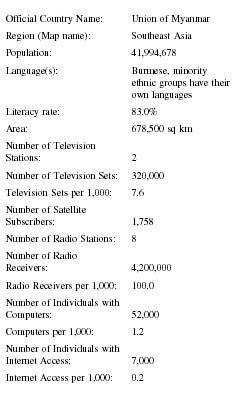

| Official Country Name: | Union of Myanmar |

| Region (Map name): | Southeast Asia |

| Population: | 41,994,678 |

| Language(s): | Burmese, minority ethnic groups have their own languages |

| Literacy rate: | 83.0% |

| Area: | 678,500 sq km |

| Number of Television Stations: | 2 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 320,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 7.6 |

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 1,758 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 8 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 4,200,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 100.0 |

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 52,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 1.2 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 7,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 0.2 |

Background & General Characteristics

Censorship characterizes Myanmar media. The Union of Myanmar, as Burma was renamed in 1989 after a military junta established the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), is controlled by a rigid socialist government directed by the armed forces. Media can only report news sanctioned by the government. Minimal international news is reported. Aung Zaw, editor of Irrawaddy magazine, described journalism in Myanmar as "comatose."

At least four Burmese-language and two English daily newspapers circulate. Myanmar newspapers print official decrees such as the 1982 citizenship law. Myanma Alin (New Light of Myanmar), published since 1914, is distributed in four languages and contains daily government press releases and negative international wire articles about countries critical of Myanmar. Editorial cartoons denounce the opposition's National League for Democracy. In summer 1988, Burmese media briefly experienced relaxation of rigid rules. Millions of democratic protestors peacefully demonstrated. Government newspapers reported factually about this democratic movement, and newspapers and periodicals were created to chronicle events. On September 18, the military led by Lieutenant General Khin Nyunt violently subdued the protestors. The junta stopped all but two newspapers, and they reverted to printing warnings, military slogans, and martial laws for Burmese citizens. Khin Nyunt blamed the media for provoking the demonstrations and accused reporters of falsifying stories.

Conditions for Burmese journalists have worsened. Monitored by the Military Intelligence Service, imprisonment, or hard labor sentences, reporters cautiously prepare media that the government cannot interpret as offensive. Myanmar officials are especially angered by media they think might cause people to regard the government disrespectfully. Most Burmese realize that news is for the most part manufactured to portray the junta as Myanmar's best rulers.

Imprisoned Burmese editors San San Nweh and U Win Tin received the 2001 Golden Pen of Freedom from the World Association of Newspapers. Charged with supporting freedom of expression and democracy, the editors refused to denounce those beliefs in order to be released. Like many jailed Burmese journalists, they suffered poor health due to their captivity and beatings by prison guards. San San Nweh was specifically arrested for giving human rights reports to European journalists. Editor of the daily Hanthawati newspaper, U Win Tin was tried and convicted by a military court for allegations of belonging to the Communist Party of Burma. His incarceration was lengthened because writing materials were found in his cell.

Burmese media professionals have persevered. Exiled Burmese journalists can write factually about their homeland for international media use. Many Burmese journalists live in Thailand so they can clandestinely distribute publications into neighboring Myanmar. In Norway, the Democratic Voice of Burma is a dissident news service.

State-Press Relations

Prior to military rule in the late twentieth century, Burma had an active media. Burma's first newspaper, The Maulmain Chronicle , was published in 1836 as an English weekly while Burma was a British colony. The Burmese monarch, King Mindon, encouraged newspaper publication and entertained editors at his palace. He supported the creation of Yadanaopon , the first newspaper printed entirely in Burmese. The media was essential in resisting colonial rulers. Burma gained independence from Great Britain in 1948. At least thirty Burmese, English, and Chinese language newspapers were permitted to report domestic and international news, interview prime ministers, and interact with journalists worldwide. U Thaung founded Kyemon (The Mirror Daily) in 1957, and its 90,000 circulation was Burma's largest. Although most southeastern Asian governments promoted state-regulated censorship, Burma supported freedom of the press.

A 1962 military coup which resulted in General Ne Win declaring himself dictator of Burma altered the country's media. Wanting to isolate Burma to achieve his socialist agenda, the general decided which newspapers could be nationalized and remain in circulation and which publications would be halted. He formed the Press Scrutiny Board, which still existed in the early twenty-first century, to regulate censorship. All journalism organizations were disbanded. Ne Win demanded the arrest of media professionals he considered hostile to his policies. Foreign journalists were ordered to depart Burma, and many Burmese reporters either quit their jobs or went into exile.

Political parties were united into the Burma Socialist Program Party, which further tightened control of the press. The 1962 Printers' and Publishers' Registration Act stated that only government-approved media could apply for the annual licenses that were mandatory for operation. Media was ordered to focus on topics supportive of Burma's socialist revolution. By December 1965, private newspapers were forbidden. Military leaders established The Working People's Daily as the official distributor of government news. The bureaucracy controlled access to limited supplies of newsprint and paper. The traditional Burmese media was effectively paralyzed.

Censorship

Censorship involves inking over passages, tearing out pages, and preventing material from being printed by reviewing material before approving it for publication. Many magazines and books in Myanmar are missing thick sections and covered with black ink. Some censors can be bribed to assure publication.

The government tries to block news regarding any negative events in Burma, with the end of keeping the current government in power. Because reporters cannot prepare factual accounts about topics that the government considers taboo, news is unreliable. Political enemies such as opposition leaders are described unfavorably, and all state-owned media is required to present these opinions. Events that are covered internationally, such as opposition leader and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Aung San Suu Kyi's release in 1995, are restricted from Myanmar media. The Ministry of Information indoctrinates government journalists at journalism courses. Reporters are expected to write pro-government propaganda and never criticize leaders or their political actions. Articles are not to mention political corruption, reform, education, and HIV/AIDS. Even stories telling about losing Myanmar sports teams and torrential rainstorms are forbidden. The press is not welcome at government meetings.

In 1998, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) identified Myanmar and Indonesia as the most hostile Asian environments for media. Rumors circulated that Myanmar military police had tortured and killed two journalists because their newspaper, The Mirror , had accidentally published a photograph of Khin Nyunt next to a headline describing criminals. Such placement of photographs and headlines has occasionally occurred, and readers realize it might be a subversive reaction to enduring censorship laws and political conditions. Journalists often try to hide information and criticisms in media through careful wording or images.

Unlike other newspapers in Myanmar, The Myanmar Times is not forced to comply with junta press regulations. Published weekly in Burmese and English at Rangoon since 2000, The Myanmar Times , with a total circulation of 30,000, is edited by an Australian journalist, Ross Dunkley. He has been permitted to print exclusive articles about discussions between the Myanmar junta and Suu Kyi. Media professionals speculate that Dunkley is allowed more press freedom because Khin Nyunt and Office of Strategic Studies (OSS) representatives are using The Myanmar Times to convince international readers to accept the junta. Other publications are also designed to attract foreign approval, especially in the form of investments. For example, in the 1990s, the monthly business magazines Dana (Prosperity) and Myanmar Dana were issued in a superior quality compared to other Burmese media in order to impress readers.

Attitude Toward Foreign Media

Any international news included in Myanmar media is censored. Events such as political strife, deposed leaders, human rights trials, and student protests in other countries, especially in Asia, are either omitted or described briefly with no details. Foreign reporters are discouraged from visiting Myanmar and sometimes can only enter the country by concealing their profession and securing a tourist visa. The junta deports and blacklists foreign correspondents who attempt to report on the opposition movement. Any reporters that the Myanmar authorities allow in the country are closely monitored.

Broadcast Media

Because Myanmar is impoverished, isolated, and only has electrical services in approximately 10 percent of its territory, people have limited use of radios and televisions. Sources estimated that there were 3.3 million radios and 80,000 televisions in Myanmar in 2001. The Myanmar government radio station, Burma Broadcasting Service, airs broadcasts that primarily reach urban populations. The government-monitored transmissions play only approved programs, which do not include Western songs or other broadcasts considered contrary to government policies. Shortwave radios are the only means for Burmese residents to gain access to foreign news reports. Some Burmese can receive Voice of America and British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) programming. They can also secretly broadcast reports to listeners who can pick up their signal.

Initiated in 1980, the government-owned television station has color transmission capabilities but only broadcasts a few shows on evenings and weekends. The Video Act of 1985 outlined what media could tape. Internet access in Burma is rare, and computer laws require government approval for use or ownership of computers, modems, and fax machines which can connect Myanmar with international resources and influences.

Bibliography

Bunge, Frederica M., ed. Burma: A Country Study . 3rd ed. Washington, DC: Federal Research Division Library of Congress, 1983.

Luzoe. Myanmar Newspaper Reader . Kensington, MD: Dunwoody Press, 1996.

Neumann, A. Lin. "The Survival of Burmese Journalism." Harvard Asia Quarterly 6 (Winter 2002). Available from www.fas.harvard.edu .

Nunn, Godfrey R., compiler. Burmese and Thai Newspapers: An International Union List . Taipei: Ch'eng-wen Pub. Co., 1972.

Thaung, U. A Journalist, a General, and an Army in Burma . Bangkok: White Lotus, 1995.

Elizabeth D. Schafer