Nicaragua

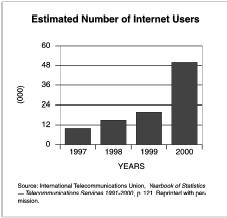

Basic Data

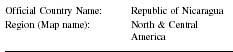

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Nicaragua |

| Region (Map name): | North & Central America |

| Population: | 4,918,393 |

| Language(s): | Spanish (official) |

| Literacy rate: | 65.7% |

| Area: | 129,494 sq km |

| GDP: | 2,396 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Television Stations: | 3 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 320,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 65.1 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 55,080 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 10.8 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 96 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 1,240,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 252.1 |

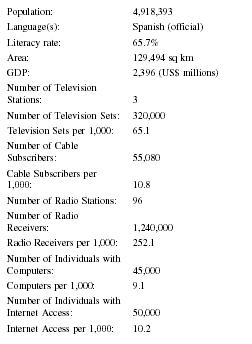

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 45,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 9.1 |

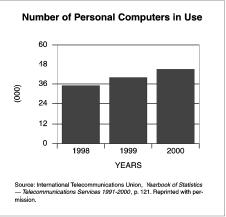

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 50,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 10.2 |

Background & General Characteristics

Since the 1970s, war, earthquakes, hurricanes, and famine have taken their toll on Nicaragua. Nicaragua managed to survive the 1980s when the Sandinista-Contra war polarized the country in a brutal civil war. Peace, however, has been less than kind since it came accompanied with natural disasters, like Hurricane Mitch in 1998 that killed over 2,000 people, made hundreds of thousands homeless, and left the country with billions in damage.

Bordered by Costa Rica and Honduras, Nicaragua has about 5 million people most of whom are mestizos (mixed European and indigenous heritage). One out of every five Nicaraguans lives in Managua, the capital city. The largest country in Central America, Nicaragua covers 130,688 square kilometers. The dominant language is Spanish (95 percent) with English Creole and Miskito spoken to some extent in the Caribbean region. Most people are Roman Catholic but evangelical Protestantism is making great headway in the region in general.

The country has 36 political parties but most forge alliances with like-minded groups in the political elections. The center-right Liberal Alliance has been in power since 1996. The adult illiteracy rate averages 34 percent; in Latin America as a whole, the average is approximately 13 percent. The nation's gross domestic product makes Nicaragua one of the poorest countries in the western hemisphere—only Haiti ranks lower in terms of per capita gross domestic product. The nation has also suffered from unemployment rates that have reached as high as 80 percent. As these statistics suggest, Nicaragua is a country of extremes with only a very small middle class wedged between the very wealthy and very poor. The United Nations Population Fund estimated that in 1998 about 70 percent of Nicaraguans were living on less than US $1 a day.

Despite the fact that the majority of the population cannot afford to buy a newspaper, the press plays a fundamental role in national affairs and in the formation and expression of elite as well as broader public opinion. Nicaraguan journalism has been intricately bound up with the nation's political and ideological struggles. Traditionally, politicians have owned the media and use it as an instrument to bestow favors upon their political allies or to attack adversaries. Despite the fact that the nation's civil war has ended and the country has embarked on the same neo-liberal political and economic programs of the majority of its Latin American neighbors, the press remains polarized between supporters and detractors of the parties who are in power.

In 1502, the first Europeans came to Nicaragua. In 1522, a Spanish exploratory mission reached the southern shores of Lago de Nicaragua (Lake Nicaragua). A few years later the Spanish colonized the region and founded the cities of Granada and León. The two cities developed into two bitterly opposed political factions. The conservatives who supported the traditional landed classes and the Catholic Church were based in the rich colonial city of Granada while León became a center for the country's political elite, adherents to political and economic liberalism. Liberals supported the interests of merchants and smaller farmers and the opening up of trade.

Nicaragua gained independence from Spain in 1821, along with the rest of Central America. It was part of Mexico for a brief time, then part of the Central American Federation, and finally achieved complete independence in 1838. The first printing press arrived in Granada a few years after independence in 1829, relatively late by Latin American standards. Not to be outdone by their antagonists, a press began operating in León in 1833. Soon after, the next three largest cities had type shops and presses. The first newspaper, Gaceta de Nicaragua , began in August 1830, the second, La Opinión Pública , in 1833. These first newspapers were of small size and few pages, and usually reprinted laws and governmental decrees. After 1840, the newspapers improved in quality and quantity, inserting essays, editorials and verse among the official decrees. At the same time, the elite began publishing broadsides to disseminate information, usually political in nature. Libraries were not common and printed material as well as education remained out of reach for all but the nation's elite.

After independence, Britain and the United States both became extremely interested in Nicaragua and the strategically important Río San Juan navigable passage from Lake Nicaragua to the Caribbean. In 1848, the British seized the port and renamed it Greytown. It became a major transit point for hordes of hopefuls looking for the quickest route to Californian gold.

In 1855, the liberals of León invited William Walker, a self-styled filibuster intent on taking over Latin American territory, to help seize power from the conservatives based in Granada. Walker and his band of mercenaries took Granada easily, and he proclaimed himself president. He was soon booted out of the country (one of his first acts was to institutionalize slavery) and eventually killed when he tried to come back.

Walker foreshadowed continual U.S. intervention in the nation. For example, the U.S. Marines were stationed there between 1912 and 1925, ostensibly to support democracy in the region, but more concerned with U.S. investments that would profit from political stability. In 1926, the contentious divisions between the nation's conservative and liberal factions were still aflame and the Marines intervened whenever things got too hot.

The turbulent 1920s resulted in the political arrival of two men who would leave their legacies on the nation: Augusto Sandino, a Liberal general, and Anastasio Somoza, head of the Nicaraguan National Guard that had been trained by the Marines. Somoza took power and gave the orders to assassinate his enemy, Sandino, on February 21, 1934. The socialist-leaning Sandinistas took their name from Somoza's martyred opponent.

Somoza was assassinated in 1956 but the dynasty continued with his sons who ruled Nicaragua until 1979. They amassed great wealth, including land holdings equal to the size of El Salvador. Many journalists were killed during this time. Somoza had his own newspaper, Novedades , and promoted media owned and controlled by family and friends. There were violent repercussions for any journalists who criticized the National Guard. Somoza's indefatigable opponent, La Prensa , was often censored and had to dispatch news critical of Somoza from the radio airwaves of Radio Sandino.

The beginning of the end for the dictatorship came when a 1972 earthquake devastated the capital city. The Somozas pocketed a good portion of the foreign aid that came in at this time, going so far as to sell for profit the donated blood that was supposed to be given to the quake victims. Clearly, the Somoza era was not a great time for freedom of the press. The number of daily newspapers declined from nine in 1950 to four in 1972. After the earthquake, only two newspapers continued to operate: La Prensa and Novedades .

The Somoza's iron-fist approach to rule inevitably led to the development of a strong opposition. The dynasty's most powerful media opponent was La Prensa , edited by Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Cardenal. Chamorro came from one of the most prominent families in the country—the Chamorros were known for their intellectual and reformist streak. Many of the family members had worked as journalists and more than one have served as president at some time (Fruto Chamorro was Nicaragua's first president; three other Chamorros presided over the nation between 1875 and 1923). Needless to say, Pedro Chamorro's demise at the hands of Somoza's assassins in 1978 was not an event taken lightly. Rather, Chamorro's murder turned into the spark that ignited the powder keg of Nicaraguan politics. A bloody revolution followed, and a coalition of Somoza's opponents placed the Sandinistas in power in 1979.

The Sandinistas inherited a poverty-stricken country with high rates of homelessness and illiteracy and insufficient health care. The new government nationalized the lands of the Somozas and established farming cooperatives. They waged a massive education campaign that reduced illiteracy from 50 to 13 percent. They also built up a large state apparatus that closely controlled the media.

From the U.S. point of view, the Sandinista victory turned Nicaragua into a teetering domino poised to fall onto the rest of Central America. In this scenario, one communist nation would topple neighboring "democratic" regimes ultimately turning the "backyard" of the United States into one large swath of communism. Seeing red, so to speak, one of Ronald Reagan's first projects upon taking office in 1981 was to suspend aid to Nicaragua and then to allocate US $10 million for the organization of counter-revolutionary groups known as Contras. The Sandinistas responded by using much of the nation's resources to defend themselves against the US-funded insurgency. The Contras and Sandinistas engaged in a devastating civil war for many years, and over 50,000 lives were lost.

In 1984, elections were held in which Daniel Ortega, the leader of the Sandinistas, won 67 percent of the vote. The following year, the United States imposed a trade embargo that lasted five years and strangled Nicaragua's economy. Even though the U.S. Congress passed a number of bills that called for an end to the funding, U.S. support for the Contras continued secretly until the so-called Irangate scandal revealed that the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency had illegally sold weapons to Iran at inflated prices, and used the profits to fund the Contras.

In 1990, Nicaraguans went to the polls and, to the great surprise of many, elected Violeta Chamorro, leader of the opposition party, UNO, and widow of martyred editor Pedro Chamorro. She proclaimed an end to fighting and announced unconditional amnesty for political crimes. Sandinistas still had strong representation in the National Assembly and they continued to control the armed forces and labor unions. During her time in office, Violeta Chamorro worked toward consolidating democratic institutions, greatly reducing the size of the military, privatizing state-owned enterprises, and fortifying the freedom of the press.

Apologizing for Sandinista "excesses" and calling himself a centrist, Ortega ran for office in 1996. He was defeated by the ex-mayor of Managua, anticommunist Liberal Alliance candidate, Arnoldo Alemán who took office in 1997. Alemán's presidency was marked by a bitter relationship with the press. During his rule, journalists complained of constant violations, mistreatment, threats of imprisonment, and verbal repression. Alemán left office amidst charges of corruption in 2001. His vice-president, Enrique Bolaños, won the 2001 election, defeating his Sandinista opponent, the ubiquitous Ortega. Although they may not hold the presidency, the Sandinistas remain a powerful political party.

As the history of the nation suggests, the communications media play a fundamental role in national affairs. Journalists and journalism have been intricately tied to the nation's power brokers, who often owned the primary media instruments. Thus, media laws and the extent to which they are protected or enforced vary greatly from president to president. The country's dramatic political and economic shifts, from the dictatorship of the Somoza dynasty to the Marxist Sandinistas to the recent trend of neo-liberalism, have forced the media to rapidly change with the times as well.

Nicaragua currently has three daily newspapers, of which La Prensa is the oldest and most established. The paper was founded with a political pedigree beginning as an instrument of the Conservative Party to battle the Liberals headed by the Somozas. Pedro Chamorro, Sr., became editor of the paper in 1930 and bought it in 1932. Pedro Chamorro, Jr., became the editor in 1952 after his father's death. After the younger Chamorro was assassinated in 1978, the paper continued to be published with a large photo of him appearing on the cover, turning the martyred editor into a powerful symbol of the brutality of the Somoza regime. The National Guard burned down La Prensa 's offices in 1979 but succeeded only in shutting down the paper for a few months.

La Prensa is considered Nicaragua's leading newspaper. It has been a powerful political instrument that continued its opposition stance even during the Sandinista era. (It originally supported the Sandinistas but soon began opposing them.) Since 1998, the news staff has undertaken more investigative reporting and political cartoons take aim at the entire political spectrum.

When Chamorro's widow, Violeta Chamorro, became president, the paper had to create a new identity from its former role as constant opponent to the ruling party. Coverage during her presidency fluctuated a great deal; sometimes the paper was closely aligned with the government and at other times opposed it. In 1996, it began to be distributed in the morning, ending its run as an afternoon paper. It also revamped its look. Two years later, when the Liberal Alliance took power, the long-time editor, Pablo Antonio Cuadra Cardenal, resigned, and three other editors left to start the newspaper La Noticia , supporting Alemán. La Prensa , as a result, became more critical of the ruling Liberal government. In an attempt to break away from a political affiliation with the Chamorro family, this new La Prensa prohibited the employment of other members of that family.

La Prensa is a broadsheet and uses six columns on the front page. It has a series of weekly supplements including La Prensa Literaria , an eight-page tabloid-sized literary supplement. It has a daily features section and a weekly magazine that comprises several pages. It also has a children's supplement and a popular commentary section that features political cartoons and spoofs of politicians from the entire political spectrum. It averages 36 pages. La Prensa 's most popular topics are government actions, reports, speeches, decrees or rulings and coverage of municipal issues. It also emphasizes economic news.

La Noticia de Managua opened on May 3, 1999 backed by the three top editors were from La Prensa . The newspaper attempted to cover more positive news stories than the other primary dailies and also filled a gap as the only afternoon newspaper. La Noticia cost the same as the three other primary papers: La Tribuna , La Prensa , and El Nuevo Diario (3 córdobas ). It remains the country's only afternoon paper. La Noticia 's editors say that the paper is independent and not affiliated with a political party, citing the fact that it has seventy different investors in the enterprise. However, there has been evidence that the paper benefited from Alemán's presidency since it received a larger portion of governmental advertising than other the other dailies which had much larger circulation rates. La Noticia concentrates its coverage on Managua rather than the nation as a whole.

The Chamorro family was by no means monolithic in its political affiliation and their involvement in the press reflects a wide range of ideologies. Early on the family was torn about their support of the Sandinistas. Pedro and Violeta's four children reflect this. Their son, Pedro Joaquín, led La Prensa in opposition to the Sandinistas. Carlos Chamorro, on the other hand, took over the official Sandinista daily, Barricada . The daughters followed the ideological split of the sons with Cristiana working at La Prensa , whereas Claudia became the Sandinistas' ambassador to Costa Rica.

Pedro Chamorro's brother, Xavier Chamorro, started El Nuevo Diario at the outset of the Sandinista revolution in 1980. The newspaper attempted to counter the coverage of La Prensa , which Xavier felt was too critical of the Sandinistas. Most of the Sandinista-supporting staff of La Prensa moved to El Nuevo Diario at its inception. El Nuevo Diario remained a Sandinista newspaper although it did criticize the party at times. This newspaper has the highest circulation in the country. It specializes in big headlines, crime stories and government scandals. It has been quite independent from the current liberal government.

About 80 percent of its issues are sold on the streets. It has the largest circulation of all of the dailies and this helps the paper remain independent since it does not need to rely on advertising as much as the other papers. The newspaper has a stable staff employing many of the nation's top reporters and photographers. Overall, however, the paper has a reputation for being sensationalistic although it has undertaken a good deal of investigative reports exposing governmental corruption.

The paper eschews too much use of color in its publication saying that the cost would not be recouped in sales. It is a broadsheet and uses five column widths on the front page. Its headlines are about three times larger than La Prensa ; it also makes generous use of subheadings, giving it a busy look. In content, it covers the same type of stories covered by La Prensa but has less emphasis on economic matters. It relies more than the others on stories of crime, corruption, and scandal to sell papers. It averages 21 pages.

Due to the tight alignment between the press and politics, a change in political leadership can have devastating effects on newspapers. The following two publications, for example, were important publications but have recently closed. La Tribuna was started in 1993 by banker Haroldo Montealegre who ran for president in 1996. La Tribuna suffered from poor circulation and finally closed in 2000. Although the newspaper was independent it, not surprisingly, supported Montealegre's run for president. La Tribuna had a high rate of employment turnover, making the paper appear questionable to much of the public, who also noticed its shifting political alliance. It began as a black-and-white tabloid but then turned to a broadsheet style in February 1994. In 1997, the paper added new sections, including a culture magazine on Fridays, and stressed its political independence. It averaged 21 pages.

Barricada was started by the Sandinistas in 1979 shortly after the revolution. It was the official paper of the Sandinistas. The newspaper got an unintended helping hand from Somoza when his paper Novedades donated its office equipment and supplies to the Sandinista start-up. Barricada 's name referred to the barricades set up in many areas during the revolution to prevent the National Guard from entering. The newspaper was edited by Carlos Fernando Chamorro, son of Pedro and Violeta Chamorro. Barricada was primarily political and represented Sandinista ideas in its first years. However, in the 1990s, the paper became increasingly sensationalistic. In 1994 the Sandinista party replaced Carlos Chamorro with Tomás Borge, the former Nicaraguan Ministry of the Interior. At this point about 80 percent of the journalists left, further damaging the paper's credibility with the public.

An additional problem faced by Barricada was the fact that the ruling Liberal government pulled back state advertisements in an attempt to challenge the newspaper. This resulted in a 75 percent drop in advertising. Barrica da closed in January 1998. Two months later it reopened as the official Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) weekly newspaper. Dependent on local party members for its circulation, Barricada 's new incarnation proved brief: the paper closed down in July of 1998. While it existed, it averaged 17 pages in length and like the other papers in the nation was a broadsheet. Borge, the publisher, blamed the paper's woes largely on the administration of President Alemán, accusing him of instituting a governmental advertising embargo against the newspaper that had slowly strangled it. Alemán denied the charges saying that the paper was poorly managed.

The degree to which this small nation can sustain its three dailies is questionable. All newspapers suffer from low circulation. El Diario has the greatest circulation followed by La Prensa , La Tribuna (until it closed), and then La Noticia . Circulation numbers vary from one source to another, ranging from 50,000 to 135,000 papers sold daily. In 1996, UNESCO estimated the circulation of daily newspapers as 32 per 1,000 inhabitants, down from 50 in 1990.

Newspaper circulation has decreased for a few reasons. One, the economy is so bad that the majority cannot afford a paper. Two, peace sells fewer newspapers than wartime—circulation rates increase considerably during moments of crisis in Nicaragua. Newspapers, however, had substantial influence on other forms of media as radio and TV stations often took their lead stories from the headlines of the printed press.

Several other weekly newspapers and magazines exist. Bolsa de Noticias is published each weekday. It was founded in 1974. It has brief news items and covers business interests thoroughly. It costs about US $360 a year to subscribe. Confidencial is a weekly newsletter headed by Carlos Chamorro (former Barricada editor). It costs about US $150 a year to subscribe. The readers of these tend to be government officials, business owners, and journalists. Other weeklies include 7 Días and El Semanario .

Most print media is centered in Managua. In rural areas, radio is much more important, and the number of radio stations has greatly increased over the last decade or so.

Economic Framework

The prevailing economic ideology, dictated by the likes of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, involves widespread privatization and deregulation. This high-speed "structural adjustment" has reduced inflation, provided ready cash for the business elite and left much of the rest of the country unemployed or in a state of sticker shock. The good news is that throughout this period human rights have largely been respected and the country's battles are now confined to the political arena.

Nicaragua is the biggest country in Central America but its gross domestic products is less than one-ninth of that in neighboring Costa Rica. Lacking substantial mineral resources, the country has traditionally relied on agricultural exports to sustain its economy. The Sandinista-Contra war took a heavy toll on the nation's economy. By 1990, when the Sandinistas were defeated in elections held as part of a peace agreement, Nicaragua's per capita income had fallen by over 33 percent from its 1980 level, its infrastructure was in tatters and its modest tourism industry had all but collapsed. The advent of peace brought some economic growth, lower inflation and lower unemployment.

In terms of the media, there have been frequent charges that the government has tried to control the press by selectively doling out governmental advertisements. These charges were especially prolific during Alemán's administration. Many newspapers that published articles criticizing his government saw a drastic reduction in government advertising, whereas those favorable to his administration received the bulk of it.

Alemán's government was the country's largest advertiser. La Prensa denounced the government tax agency for placing 6.4 times more advertising with La Noticia than with La Prensa during a six-month period, even though La Prensa 's circulation was almost 10 times that of La Noticia . In 1998, two large governmental agencies did suspend their ads in La Prensa .

The government has also been charged with harassing papers by overzealous taxation. La Prensa decried government attempts to collect more than US $500,000 in tax penalties from the paper. The penalties resulted from a 1999 audit that was conducted shortly after La Prensa published a report on government corruption. Television channels 2 and 8 also complained that they were being fiscally punished by the Alemán government for their negative coverage of his administration.

Even Alemán's attempt to pass a minimum wage law for journalists was controversial. The new bill, passed in 2000, established a special schedule for journalists that is separate from the national minimum wage bill. It is feared that the enforcement of this law could reduce the news flow to the Nicaraguan people because many media organizations would have to reduce their coverage.

The recently elected president, Enrique Bolaños, a member of the same party as his predecessor, Alemán, announced that his policies on the media and placement of government advertising would be a departure from Alemán's. He promised to end the policies of awards and punishments used in placement of government advertising. Instead, government advertising would be placed according to readership surveys and circulation. Bolaños has also promised that the government-owned television and radio stations would be used for cultural purposes and not partisan political programs.

Although Bolaños has promised these reforms, as of 2002 it was still too early to see if effective action had been taken. There have already been signs of tension between Bolaños and the press. For example, radio commentator Emilio Núñez was dismissed from a program he ran on Radio Corporación by the stockholder and manger Fabio Gadea Mantilla after Núñez reported an alleged government plan to force the company's journalists into submission with an economic stranglehold. Bolaños said he had nothing to do with the case and that he would adhere to the Declaration of Chapultepec in placement of government advertising. Bolaños was referring a conference that took place in Mexico in 1994 also known as the "Hemisphere Conference on Free Speech," sponsored by the Inter-American Press Association. The declaration established 10 principles that should be in place for freedom of the press to exist. One of the principles states: "There must be a clear distinction between news and advertising." Bolaños had already signed the Declaration of Chapultepec when he was a presidential candidate.

Bolaños took advantage of Nicaraguan Journalists Day, March 1, to reiterate that government advertising would be distributed fairly. He also said that he had reviewed the former administration's advertising policies and noted that he found many irregularities, promising to publish the finalized results.

La Noticia has recently alleged that it is discriminated against in the placement of government advertising. The newspaper complained, for example, that on Journalists' Day of 2002, La Prensa and El Nuevo Diario received ads congratulating journalists that measured 90 column-inches each, whereas La Noticia received the same ad reduced to 30 column-inches. Surveys by the Nicaraguan Advertising Agency Organization, however, show that La Noticia 's circulation is less than 3 percent of that of the other publications. La Noticia complained that, in general, it receives just half a page of ads from the government whereas La Prensa receives two pageseach day and El Nuevo Diario receives one page. This, however, may be a case of sour grapes, since in 1999 when La Noticia had only 2 percent of the nation's total newspaper circulation, it received almost 25 percent of the government ads.

There is some skepticism that Bolaños will ultimately not be too far separated from Alemán's policies since they are from the same political party and Bolaños had served as Alemán's vice president since 1996. However, Bolaños has sought to distance himself from Alemán's stained reputation, promising to fight corruption and ensure freedom of the press. Indeed, Bolaños's treatment of Alemán's pet, La Noticia , suggests that he is forging his own path. Bolaños's press secretary disclosed that he was a stockholder in La Noticia and, as such, he believes that La Noticia should be closed because its circulation is low and it is not profitable. The newspaper and other media outlets that support the Liberal Alliance of Alemán reacted to his statements by accusing the Bolaños government of threatening press freedom.

Although Alemán is no longer president, he wields considerable power as head of the National Assembly. In March 2002, for example, he accused Octavio Sacasa, news director and general manger of Channel 2 television, of allegedly threatening him with death. Sacasa emphatically denied Alemán's charge and, in turn, accused the former president of trying to intimidate the media to prevent further reporting on corruption. As of mid-2002, this case was still pending.

The Bolaños administration has not turned away from investigating many charges about Alemán's alleged corruption. Currently, the government is investigating a fraudulent contract through which the state television channel, Channel 6, reportedly lost US $1.35 million. The scheme is said to have included 35 participants, including Alemán and the former Mexican Ambassador to Nicaragua. The case involves a contract for Mexico's TV Azteca to provide programming to Channel 6 through a newly formed Panamanian company, Servicios Internacionales Casco. The deal was allegedly used to import duty-free equipment into Nicaragua. There were charges that those involved tried to collect on a US $350,000 check that the government's Nicaraguan Tourism Institute had issued to Channel 6. A former Channel 6 director has also been implicated.

Press Laws

The Nicaraguan constitution provides that "Nicaraguans have the right freely to express their ideas in public or in private, individually or collectively, verbally, in writing or by any other means." However, there are a number of other laws and regulations that chip away at freedom of the press.

In 1995, the Constitution of 1987 was reformed and several new articles were added related to the press. For example, Article 68 declared that the media had a social role to fulfill and that its practitioners should have access to all of the nation's citizenry in order to fulfill their role. This article also exempts media companies from taxes on importing newsprint, machinery, equipment and spare parts intended for use by the print and broadcast media. The constitution also prohibits prior censorship. Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, there have been some small steps both forward and backward in regard to press freedom and legislation. In May 2000, the National Assembly approved a version of the new criminal code that includes a guarantee for the right of information. However, the code also includes individual privacy protection, a provision that may hamper investigative reporting.

Journalists are also subject to lawsuits in regard to libel and slander. Many cases finding journalists guilty of slander, however, have been overturned including a 1997 case that found La Prensa president Jaime Chamor ro guilty of libeling La Tribuna editor Montealegre. A libel and defamation suit against Tomás Borge, editor of Barricada , was dismissed after he apologized in court and in print to a congressional candidate whom Barricada had said was a shareholder in the firm that prints election ballots.

In December 2000, Nicaragua passed an extremely controversial bill requiring the compulsory registration of journalists in the colegio (professional association) of journalists in Nicaragua. In 1985, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in Costa Rica ruled that laws requiring the mandatory licensing of journalists violate the American Convention on Human Rights. These colegio laws have often been controversial in Latin America. The United States and many Latin American news organizations view colegio laws as government attempts to control the press. The laws are regularly condemned during meetings of the Inter American Press Association (IAPA), the major media watchdog group in the Western Hemisphere.

The law requires all journalists to register as members of the institute and have a journalism diploma and proof of at least five years experience in the profession. The law was first passed on December 13, 2000, after which Alemán introduced amendments providing for jail terms of up to six months for anyone who worked as a journalist without registering with the colegio . The appeal of the constitutionality of this law, brought before the Supreme Court, has not yet been decided.

In December 2001, several liberal legislators proposed a Law of Restrictions on Pornographic Publications. Although a law against pornography would not violate press freedom, the proposed law would give governmental committees authority to restrict and punish publication of what it considers pornographic or violent. The law also authorizes the closing of a written publication's pornography sections if an offense recurs. As of mid-2002, the law was pending approval.

In terms of the broadcast media in 1996, a general law of telecommunications and postal services was passed requiring that information transmitted should not be contrary to the customs and moral values of the nation. It also established the conditions for the awarding of technical concessions and operating licenses. The majority of radio stations are operated on a small-scale by volunteers. These radio stations are not regulated.

Censorship

During the late 1990s and early 2000s there were very few incidences of outright censorship in Nicaragua. The IAPA confirmed that freedom of the press had improved dramatically since the days of the Somoza dictatorship and the Sandinista government. The constitution provides for freedom of speech and a free press, and the government, in general, respects these rights in practice. The privately owned print media, the broadcast media, and academic circles freely and openly discussed diverse viewpoints in public discourse without government interference. This was not always the case. The Somozas regularly censored the opposition newspaper La Prensa . During the 1970s, as the press became increasingly critical, censorship was increasingly used to control it.

Likewise, the Sandinistas used censorship as a tool in an attempt to restrain an unfavorable press. The Sandinista party declared a state of emergency as a result of the Contra war, giving itself broad power to restrict press rights. It shut down La Prensa many times. The process of getting the newspaper's content reviewed on a daily basis grew increasingly lengthy (about 7 hours in the mid-1980s). This put the paper at a disadvantage for obvious reasons and also because it forced the paper to hit the stands hours after the Sandinista morning papers, Barricada and El Nuevo Diario .

On several occasions during the 1989-90 electoral campaign, international observer missions expressed their concerns that mud-slinging in the media on both sides threatened to undermine an otherwise orderly and clean election. There have been other intermittent charges of actual censorship cases. For example, former vice-president Sergio Ramirez Mercado sent a letter to President Violeta Chamorro declaring that he had been censored on the state-owned television channel. Ramirez insisted that Chamorro had banned the broadcast of his interview scheduled on the cultural program, "This is Nicaragua." The presidential media chief denied the charges.

In terms of broadcast media, there has not been any official state censorship practiced and journalists say that little self-censorship has occurred.

State-Press Relations

The relations between the state and the press fluctuate according to the political climate of the times. Despite charges against the Sandinistas for exercising acts of censorship in the news media, there is evidence that the Sandinistas also made attempts to transform the media institutions as a source of empowerment for the citizens. Such initiatives were based on a democratic model of media structure and access unique in Latin America. Its features included an attempt to balance the ownership of media outlets among public, private, and cooperative forms; to encourage political and ideological pluralism in media content; and to promote popular participation and horizontal communication through the mass media.

The underlying philosophy was that the media, instead of serving the narrow interests of a wealthy elite, should become the vehicles for expression of the opinions of the broad majority of society, and that notions of social responsibility should guide the media's activities as opposed to narrowly defined profit motives. For example, the Sandinistas banned the use of women's bodies to advertise products. However, many of their experiments in participatory and community radio, popular access to state-owned television, and the birth of dozens of new print publications were cut short by war-related restrictions and economic constraints.

Violeta Chamorro's presidency beginning in 1990 was accompanied by major shakeups in the ownership and content of many of the country's existing media outlets as well as the creation of dozens of new ones. La Prensa found itself confronted with a serious dilemma. For decades the paper's mystique had been built upon its image as the "bastion of opposition." In a political culture that thrived on criticism of those in power and opposition to anything associated with the government, the paper suddenly became the semi-official mouthpiece of the country's president. For the most part, the newspaper largely avoided excesses of "officialdom", which had been part of the problem with Barricada during the Sandinista's rule.

Perhaps the greatest changes under Chamorro's presidency had to do with the dramatic transformation of the advertising industry from one that had previously been state-controlled and anti-capitalistic to an unfettered media-based advertising model. Between 1990 and 1994 at least 21 new advertising agencies were launched where only one had existed before. The lack of a mass consumer base, however, meant that these advertisers had to accept the reality of selling to a tiny elite. Advertising expenditures as a result dropped greatly between 1992 and 1995.

The Nicaragua media encountered problems in 1994 because every news outlet was somehow linked or openly affiliated with a political party. In this year there were many incidents of physical abuse by police against reporters covering demonstrations or other public disturbances. For example, an internal conflict between radicals and reformers erupted at Barricada . Ortega, the head of the Sandinista party, fired 16 reporters and the editor-in-chief for their alleged support of the reformist politician. The infighting became a media war with Ortega's side in control of three radio stations and one television channel, and the reformists in control of two dailies and one weekly newspaper.

In 1999, two radio stations faced legal orders for the seizure and sale at auction of their equipment. According to a statement by the National Nicaraguan Journalists Union, the radio stations La Primerísima and YA were being threatened by groups linked to then-president Alemán in an attempt to silence any public criticism of the rise in corruption by high-level officials in his regime.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

Since the turn of the twenty-first century, there has been little attempt to restrain foreign journalists in Nicaragua. During the Sandinista-Contra war, Nicaragua was an extremely dangerous place for foreign journalists, although many arrived there as a result of the conflict. For example, in June 1979, ABC news correspondent Bill Stewart was killed when he stopped at a Managua roadblock. With the advent of peace, foreign journalists have not had problems covering the region, and have been welcomed there by a number of national media enterprises attempting to make the press more professional.

The passage of the colegio law requiring that all journalists be approved by the national licensing board threatens to change this situation. In general, however, Nicaraguan journalists have looked to foreign journalists as a model for the type of journalism they are striving to follow in their nation, although some are critical of this trend.

Historically, Nicaraguan newspapers have often received international funding. During the Sandinista-Contra war, the United States gave financial support to La Prensa . In the 1980s, Barricada received funding from East Germany, a Dutch foundation gave money to El Nuevo Diario , and a West German foundation gave money to La Prensa . In the 1990s, La Tribuna hired a Costa Rican research firm to assess the coverage most wanted by Nicaraguans. Journalist professors from the Florida International University also trained some of La Tribuna 's reporters, reflecting the fact that the paper's editor was based in Florida. La Prensa hired a U.S. consultant to help modernize the paper in 1998.

There is some fear that too many foreign consultants and journalists will take away the historical Nicaraguan approach to journalism, which is more intellectual and political and has a tendency to be more detailed in writing styles than, for example, the U.S. style of journalism. A number of foreign journalist organizations have organized conferences and classes in Nicaragua on investigative journalism and the freedom of the press.

News Agencies

Agencia Nicaragüense de Noticias is the primary news agency operating in Nicaragua. A recent survey showed that journalists get about 14 percent of their stories from wire services.

Broadcast Media

The 1990s were a boom period for radio. Between 1990 and 1994 the government's telecommunications frequency authority assigned over 100 frequencies. On these, 60 were on the FM band. Previously, there had been only four FM stations. As of mid-1995, a total of 114 radio stations were broadcasting in Nicaragua. Because station start-up and maintenance costs were minimal, a number of people including aspiring politicians were able to enter into radio broadcasting. Religious programming also expanded. By 1995, there were seven new religious stations in addition to the two that already existed. There is at least one radio station in each of Nicaragua's 17 departments. Growth centered, however, in Managua, where 46 of the 60 new FM stations and 23 of the 49 new AM stations were launched. In 1999, there were 285 radios for every one thousand inhabitants.

Generally speaking, the content of radio programming is much broader than television. FM programming includes a variety of music formats, news, and listener call-in shows, and AM programming often features a mixture of news with music and opinion, traditional newscasts, music, radio dramas, humor shows, sports and listener call-in shows. Independently produced radio news programs were a popular genre before 1979 although banned in the 1980s. As of the mid-1990s listeners could choose from over 80 such programs. In most cases, these were one-person freelance undertakings where journalists rented air space from the station.

Four of the most popular radio stations include the following:

- Radio Nicaragua (formerly La Voz de Nicaragua) is the government's official station.

- Radio Corporación has long been a stronghold of the far right. Its broadcasting center was bombed in 1992. It originally defined itself by opposing the Sandinistas. It has strong family links with president Alemán. Almost all of its journalists are employees of the government and depend on state advertising revenue.

- Radio Católica belongs to the Catholic Church hierarchy. It is fairly conservative and has a large following among Nicaragua's devout Catholic majority.

- Radio Ya was founded by some 80 percent of the staff from the Voz de Nicaragua when Violeta Chamorro came to power. The station is affiliated with the Sandinistas and is often critical of the ruling government. It is one of the most listened-to stations in the nation.

Despite its status as an instrument of the Sandinistas, Radio Ya allows space for a public forum with an open mike to the citizens. The station has a net of volunteers who are not journalists but regular "civilians," such as hospital orderlies, litigants in courtrooms, and vendors in the markets who report on events as they happen. At present the station is owned by a company named Atarrya, which stands for Association of the Workers of Radio Ya, with 49 percent belonging to stock-holding employees and 51 percent to the Sandinista leadership.

Radio Sandino was the Sandinista's clandestine radio station during the guerrilla war against Somoza, and it continues to be the official voice of the Sandinista Front. La Primerísima was the flagship station of the state-owned network of community stations during the 1980s. It pioneered a series of projects in popular and participatory radio. Radio Mujer went on the air in 1991, the first radio station designed specifically for women.

Because of the relatively low expense of radio in comparison to other forms of media in the nation, radio is the dominant way the poorer classes get their information. Radio has also served practical functions especially in times of disaster. When Hurricane Mitch struck, for example, Radio Ya helped individuals locate their family members via their daily broadcasts.

Television experienced the most profound changes and the most dynamic growth of all forms of media. The

Since 1990 television has also become an important forum for the debate of national issues and politics. There have been many new live broadcast magazine-format programs including Channel 8's "Porque Nicaragua Nos Importa" (Why Nicaragua Matters to Us), and "A Fondo" (In-Depth). Channel 2 has a popular 90-minute morning program, "Buenos Días" (Good Morning) and a weekly newsmagazine program, "Esta Semana con Carlos Fernando" (This Week with Carlos Fernando) hosted by the former director of Barricada .

Electronic News Media

Most of the main newspapers in Nicaragua have Internet sites. La Prensa 's Internet site has been in operation since October 30, 1997. El Nuevo Diario (www.elnuevodiario.com. ni) began on October 30, 1997. This site is designed to be simple so that it is less costly to maintain and easier to view on older computers. The site had 382,000 hits in 1999. La Prensa has the most popular Web site, registering 1.1 million hits in 1999. Both of the now defunct papers Barricada and La Tribuna also had Web sites. The number of people with computers in Nicaragua remains small, so newspapers were not afraid that Internet sites would adversely affect their circulation. However, access to the Internet is rapidly changing the ways that Nicaraguans can get access to information, and it has become an integral tool for journalists especially. There are many obstacles to its use, however, given the prohibitively high cost of computers for the average citizen. In 1999, it is estimated that there were 50,000 Internet users in Nicaragua.

Education & Training

The main university offering journalism training is Universidad Centroamericana (UCA) in Managua, which offers a degree entitled Communication and Society that is especially prestigious. Other universities with journalism programs including the Universidad Iberoamericana de Ciencia y Tecnología and the Universidad Autónoma de Nicaragua. In 1998, a new journalism program opened in Matagalpa at the Universidad de Nicaragua Norte. The Universidad Americana de Managua began developing a journalism program in the early 2000s. The UCA program is the largest and the most established, and graduates about 50 students every year. In the 1980s the program emphasized propagandistic journalism, stressing the role of the journalist as leader and organizer. This emphasis changed with the country's political leadership in the 1990s and there was an emphasis on more democratic and professional investigative reporting.

There are an increasing amount of regional scholarships and grants for both practicing journalists and journalism students. The Latin American Center for Journalism, for example, offers the Jorge Ramos scholarship established in 1999 to enable students to finish their last year in a journalism program. A total of 10 scholarships are offered per year, and a few Nicaraguan students have won one. In 1997, the Violeta B. Chamorro foundation was established in Managua to support the growth of democratic institutions in the nation. The foundation gets international financing, primarily from Sweden, for the journalism programs. In 1998, the foundation sponsored a series of workshops on journalistic ethics investigative journalism, focusing on uncovering governmental corruption. The foundation created a national award named after Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Cardenal (Violeta's martyred husband and former La Prensa editor) to promote a democratic and free press.

There are two journalists' associations: the Association of Nicaraguan Journalists (APN) and the National Union of Journalists (UPN). Both of these organizations present a number of talks focusing on all aspects of the profession. The UPN represents the prorevolutionary faction of journalists. The two groups are often at odds with one another. For example, the UPN supported the colegio law, which was strongly opposed by the APN.

Journalism in Nicaragua is more dangerous than in most countries given that political protests and demonstrations can and do turn violent. In 1999, for example, during a student protest and transportation strike in which one student was killed, a La Prensa vehicle was set on fire. In 1997, Barricada reported a story on journalists and the dangers they face and the article discussed the case of Pablo Emilio Barreto, one of their reporters, who lost his home and belongings when a group of armed men angry at his reporting sprayed gasoline on his house and fired upon it. In 1998, the editor and publisher of the newspaper Novedades declared that a journalist had her arm broken in an assault by a policeman reportedly acting on the orders of an advisor and supporter of the then-presidential candidate Alemán. The attack was seen as retaliation for criticism in Novedades of Alemán's candidacy. Journalists also have to contend with street crime (i.e., crime that is not politically or personally motivated).

One very significant problem facing journalists in Nicaragua is the low salaries they earn, which usually run between US $150 to $250 a month. Television journalists make about double that on average. The low salaries and high unemployment rates can make journalists susceptible to accepting outright bribes or more subtle forms of influence peddling. For example, journalists can make extra money by giving publicity to businesses or for interviewing certain people on the air for fiscal compensation.

Summary

The state of Nicaragua's press has fluctuated greatly from political system to political system and president to president during the twentieth century. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, despite an antagonistic relationship with former president Alemán, the press is becoming an increasingly active protagonist in the Nicaraguan transition to neo-liberalism. The process has been characterized above all by the drive for political independence among individual journalists and media enterprises, along with the increasing importance of the electronic media, especially television but increas ingly the Internet, as mediators of politics, culture, and ideology.

Historically, the press in Nicaragua developed as an instrument to support a specific political agenda. The press retains more than a few remnants of this polarization; however, since the 1990s, the spectrum of views aired in the media has been quite extensive. Nicaraguan newspaper journalism underwent vast changes in the 1990s following a U.S. model of objective and investigative journalism. Perhaps the greatest obstacle to the development

Nonetheless, independent media watchdogs have consistently given high reports to the acceleration of freedom of the press in the nation. In addition, international pressure has focused attention on corrupt administrations and presidential attempts to control the media's negative coverage of political (and, at times, criminal) activities. President Bolaños has declared that he will not only abide by but also fortify legislation supporting freedom of the press. Overall, the attempts to move from a partisan style of journalism to a more professional and ethical style have been successful, especially given the personally and politically charged history of media ownership in the county. The news media is also gaining more support from the public, ranking second only to the Catholic Church, in terms of its institutional credibility.

Significant Dates

- 1990: Violeta Chamorro wins the presidency ending the Sandinista rule and the civil war, and maneuvers the country onto a path of neo-liberal economic policies; she stresses freedom of the press and undertakes a series of reforms to strengthen democratic institutions.

- 1995: The Nicaraguan Constitution, promulgated under the Sandinista government, is revised strengthening press freedom.

- 1997: Arnoldo Alemán ascends to the presidency. His relationship to the press is marked by controversy, and he attempts to reign in its freedom; he is accused of using the selective placement of governmental advertising to achieve these ends.

- 1998: Hurricane Mitch devastates the country, killing over 2,000 people and causes billions of dollars worth of damage.

- 1998: The Sandinista paper Barricada , one of the country's four dailies, announces that it is closing indefinitely because of a financial crisis; the paper blames its financial woes on President Alemán who allegedly withheld governmental advertising in an attempt to shut the paper down.

- 2000: The National Assembly approves a controversial bill calling for the compulsory registration of journalists in the national journalists association; this colegio law violates the principles for freedom of the press outlined by the Chapultepec convention of 1994.

- 2002: Enrique Bolaños, a Liberal Alliance candidate, assumes the presidency; despite the fact that he served as vice-president to Alemán who left office amidst a flurry of corruption charges, Bolaños promises to support freedom of the press and end the government's practice of controlling the media by choosing where to place governmental advertisements based on political preference.

Bibliography

Burns, E. Bradford. Patriarch and Folk: The Emergence of Nicaragua, 1798-1858 , Cambridge, MA: XXX, 1991.

Chamorro, Cristiana "El Caso de Nicaragua." In Periodismo, Derechos Humanos y Control del Poder Politico en Centroamerica , ed. Jaime Ordóñez, XXX. San José, Costa Rica: Instituto Interamericano de Derechos Humanos, 1994.

——. "The Challenges for Radio Ya and Radio Corporación." In Pulso del Periodismo , XXX. Miami: Florida International University International Media Center, 2000.

Cortés Domínguez, Guillermo. "Etica periodística contemporánea en Nicaragua." Sala de Prensa: Web para profesionales de la comunicación iberoamericanos 2 , 32(June 2001). Available from http:// www.saladeprensa.org/art237

Index on Censorship . March 1999.

IPI Report, 1995.

Jiménez, Ruvalcaba, and María del Carmen. El Estado de Emergencia y el Periodismo en Nicaragua . Guadalajara, Mexico: Universidad de Guadalajara, 1987.

Jones, Adam. Beyond the Barricades: Nicaragua and the Struggle for the Sandinista Press, 1979-1988 . Athens: Ohio University Press, 2002.

Kodrich, Kris. "Professionalism vs. Partisanship in Nicaraguan Newsrooms. Journalists Apply New Professional Standards." In Pulso del Periodismo , XXX. Miami: Florida International University International Media Center, 2000.

——. Tradition and Change in the Nicaraguan Press: Newspapers and Journalists in a New Democratic Era .Lanham, NY: University Press of America, 2002.

Merrill, John C. (ed.). Global Journalism: Survey of International Communication . New York: Longman, 1991.

Norsworthy, Kent W. "The Mass Media." In Nicaragua without Illusions: Regime Transition and Structural Adjustment in the 1990s, ed. Thomas Walker, XXX. Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources, 1997.

Norsworthy, Kent, and Tom Barry. Nicaragua: A Country Guide . Albuquerque, NM: The Inter-Hemispheric Education Resource Center, 1990.

Pastrán Arancibia, Adolfo. "Periodismo y salario mínimo en Nicaragua." Pulso del periodismo , XXX. Miami: Florida International University International Media Center, 2000.

Reporters Without Borders, Annual Report, 2002.

World Press Freedom Review, 1998-2001 .

Kristin McCleary