Panama

Basic Data

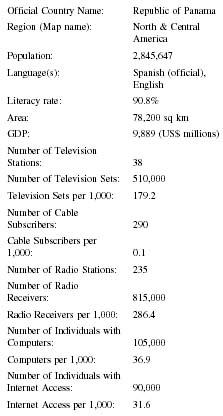

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Panama |

| Region (Map name): | North & Central America |

| Population: | 2,845,647 |

| Language(s): | Spanish (official),English |

| Literacy rate: | 90.8% |

| Area: | 78,200 sq km |

| GDP: | 9,889 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Television Stations: | 38 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 510,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 179.2 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 290 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 0.1 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 235 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 815,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 286.4 |

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 105,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 36.9 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 90,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 31.6 |

Background & General Characteristics

Panama has been both blessed and hindered by its geography and geopolitical location. It is home to some of the least densely populated terrain on earth (the Darien rain forest region) but also hosts the busy Panama Canal, which has brought the world to the country's doorstep. The building and control of the Canal has influenced Panamanian society including the important role the United States has played in Panamanian affairs, population distribution (concentrated in the canal zone), and the economy. In the early 2000s, the capital, Panama City, located on the eastern bank of the Canal, which runs a course almost directly through the middle of the country, hosted a population of 465,000.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the official language was Spanish, while approximately 14 percent of the population claimed English as their first language. According to Goodwin, most of the citizens (70 percent) were considered mestizo (a mix of European and indigenous heritage). Fourteen percent were West Indian (many of whom came to Panama to build the canal in the beginning of the twentieth century), 10 percent were European (Caucasian or White), and 6 percent were Amerindian (indigenous). Panama's indigenous populations numbered about 194,000 and they had the same political rights as other citizens. Some Amerindians, such as the San Blas Kuna, lived in self-governing districts. In 1992, the Kuna petitioned for the creation of an additional reserve to prohibit incursions by squatters into areas traditionally considered their own.

Panama was predominantly Roman Catholic (85 percent), although Protestantism was becoming more popular, as in many Latin American countries. Literacy rates were rather high for a developing country (90.8 percent), and education was compulsory and provided by the State between the ages of 6 and 15. Suffrage was universal at 18 years of age.

There were approximately 366,000 main telephone lines serving a population of 2.8 million. Daily newspaper circulation was 62 newspapers per 1,000 persons. There were 13 television sets per 1,000 residents. Panama had six Internet service providers as of the year 2000.

President Torrijos died in a plane crash in 1981, but during his administration he elevated the National Guard to a position of supreme power in the state. The 1984 elections appeared to bring to fruition the process of political liberalization initiated in 1978. While civilian rule was officially restored, the armed forces remained the real power in the country. The news that the Defense Forces chief general Manuel Noriega rigged the 1984 elections surfaced in 1987. He was also accused of drug trafficking, gun running, and money laundering. Efforts by then-president Eric Arturo Delvalle and the United States failed to remove Noriega from power. U.S. troops ultimately invaded in 1989 after Noriega called elections to legitimize his government.

While there was a new leader in power, Panama was still experiencing the same problems. The country was characterized by extremes of wealth and poverty, and corruption was endemic. The economy was still closely tied to drug-money laundering, which has reached even higher levels than during Noriega's reign.

The 1989 U.S. invasion created anti-U.S. sentiment, which was reflected, for example, in the 1994 elections. Three-quarters of the voters supported politicians who had risen in opposition to the policies and politics (including economic sanctions) imposed on Panama by the U.S. invasion.

The elected president, Ernesto Pérez Balladares, an economist and businessman and a former supporter of Noriega, promised "to close the Noriega chapter" in that country's history (Goodwin 45). He supported privatization, development of the Panama Canal Zone, and restructuring of the foreign debt, and he designed initiatives to enhance tourism. However, he seemed to also have the authoritarian tendencies of Noriega; in 1998 he supported a constitutional change that would have allowed him to run for reelection. However, the Panamanians resound-ingly defeated his ideas in 1999. Mireya Moscoso won the 1999 elections, and became Panama's first woman president.

An active and often adversarial press and a broad range of print and electronic media outlets existed, including newspapers, radio and television broadcasts, and domestic and foreign cable stations. Six national newspapers, 4 commercial television stations, 2 educational television stations, and approximately 100 radio stations provided a broad choice of informational sources. All were privately or institutionally owned except for one government-owned television station. A 1999 law prohibited newspapers from holding radio and television concessions, and vice versa. While many media outlets took identifiable editorial positions, the media carried a wide variety of political commentaries and other perspectives, both local and foreign. There was a concentration of control of television outlets in the hands of close relatives and associates of former President Pérez Balladares, who was a member of the largest political opposition party.

In July 2000 the Panamanian legislative assembly passed a bill mandating that all school textbooks in Spanish be written by Panamanian authors. However, on August 1, the president vetoed the bill.

The most read newspapers in Panama were América Panamá , CríticaLa Prensa and El Siglo , all published in Panama City. There were also the weeklies Crítica Libre and La Crónica , as well as the dailies Dario el Universal de Panamá , El Panamá América , and La Estrella de Panamá (see www.escapeartist.com or www.kidon. com for the Internet links). All of these were published in Spanish and based in the capital, Panama City.

La Prensa was created in 1980 to fight Panama's military dictatorship. It later became a thorn in the side of President Pérez Balladares because of its "take-no-prisoners muckraking of his government's officials," according to CPJ.

According to Law 22 from 1978, the publication of printed media was not subject to permits or licenses. It was only required that the Ministry of Government and Justice be notified about the name of the publication, how often it was published, where it would be printed, the names of the owners, and who would edit the paper.

Generally speaking, the constitution provided for the right of association, and it generally respected this right in practice. Panama allowed a Journalists' Union. All citizens had the right to form associations and professional or civic groups. Application for official acknowledgment as an association could be denied (as happened in 2000 with an informal gay rights organization), and might register instead as a nongovernmental organization.

Economic Framework

The Panamanian economy was based on the service industry, concentrated in banking, commerce, and tourism. Activities centered on the Panama Canal were the backbone of the national economy, and the canal was turned over to Panama on December 31, 1999 after U.S. ownership from its completion in 1914. The government relied heavily on the direct and indirect revenues generated by the canal, ignoring other types of national development. Much of Panama's economic success in the 1980s was the result of a strong service sector associated with the presence of a large number of banks, the Canal, and the Colón Free Zone. While a minority of U.S. citizens and military residing in the Canal Zone enjoyed a high standard of living, the average Panamanian lived in poverty. President Omar Torrijos became a national hero in 1977 when he signed the Panama Canal Treaties with the United States, which provided for full Panamanian control over the canal and its revenues in 1999.

The canal treaty provisions led to both optimism and concern. Officials were optimistic because they would inherit military bases, universities, ports, luxury resorts, and retirement communities. Others, however, worried about the estimated $500 million that the U.S. citizens and U.S. troops had poured in the Panamanian economy. By 1995, more than 300 poor, landless people a day were moving in the Canal Zone and were clearing forest for crops.

Mireya Elisa Moscoso de Arias, elected president on September 1, 1999, initiated some changes in economic and social policies, which directly affected freedom in the media. Her predecessor, Ernesto Perez Balladares Gonzalez Revilla, developed a rather liberal economic philosophy, attracting foreign capital, privatizing state institutions, establishing fiscal reform, and creating labor laws to stimulate employment. She opposed many of her predecessor's free-market policies and was critical of plans to further privatize state-owned industries. Her goals included issuing in a new era for Panama's poor, who constitute one-third of the population. Diversification of the economy was still needed, as Panama was overly dependent on canal revenues and traditional agricultural exports. Panama had a relatively high unemployment rate of 13 percent, which may have resulted from too much emphasis on the Canal Zone.

As is the case in most Latin American nations, Panama's constitution gave the state substantial power. It allowed the state to direct, regulate, replace, or create economic activities designed to increase the nation's wealth and to distribute the benefits of the economy to the greatest number of people. Moscoso had the constitutional authority to push for social changes, but the opposition dominated the legislature, which probably made the imposition of meaningful changes difficult.

Women gained the right to vote in 1940, and were granted equal political rights under the law. They also held a number of important public positions. However, women did not enjoy the same opportunities for advancement as their male counterparts in the domestic sphere. Panamanian law did not recognize community property. Therefore, divorced or deserted women had no protection and could be left destitute, if that were the will of their former spouses.

Press Laws

While theoretically free, the press and broadcast media experienced harassment from government officials and businesses. The Supreme Court ruled in 1983 that journalists did not need to be licensed by the government. Nevertheless, both reporters and editors still exercised a calculated self-censorship. Press conduct was regulated by the Commission on Morality and Ethics, whose powers were broad and vague. In 2001, some journalists complained that the government used criminal anti-defamation laws to intimidate the press and especially its critics.

Gag laws were an infamous element of the journalistic landscape and were a holdover from the military dictatorship. Moscoso repealed some of these gag laws implemented and enforced by Pérez Balladares. The first gag laws were introduced following a 199 coup. After that, a series of laws, decrees, and resolutions were used to stifle independent journalism in Panama. Law 11, for example, that prohibited the publication of false news, facts relating to a person's private life, or comments, references, and insinuations about a person's physical handicaps. Laws 67 and 68 gave government the authority to license journalists. (The licensing requirement was subsequently repealed.) Pérez Balladares, who left office in September 1999, promised on several occasions to repeal the laws. Instead, he used those gag laws to prosecute journalists who criticized his administration. The filing of legal actions against journalists remained an issue in the early 2000s.

Moscoso was required to submit a bill in 2000 that brought Panama's press laws up to international standards. One of the more notorious laws to be repealed was Decree 251, which authorized the National Board of Censorship. As of 2002, the pres laws provided for the establishment of a censorship board. The board monitored radio transmissions and had the authority to fine stations that violate norms regarding vulgar, profane, or obscene language.

To combat the intensification of prosecution of journalists, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) issued a letter on March 4, 1999, to the president urging him to repeal the laws. A month later, a government ombudsman published a report criticizing the "systematic and permanent campaign to silence, gag, and persecute journalists." Santiago Canton, the special rapporteur for freedom of expression of the Organization of American States, called the gag laws a "tool frequently used by public officials to silence their critics."

Perhaps in response, Pérez Balladares proposed onerous new provisions that masqueraded as an effort to reform the gag laws. CPJ wrote in a letter addressed to the president "expanding the legal means for repressing journalists is not a fitting legacy for a president who came to power pledging to strengthen Panamanian democracy."

The Inter-American Press Association noted the absence of Panamanian participants at its biannual meeting in March 2001. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) delegation visited Panama in June 2001 and asked the president to eliminate all existing vestiges of them. In addition, the IACHR recommended that the OAS amend its report on the status of freedom of speech in Panama to emphasize the repressive attitude of the country's judicial system toward the media.

Some sources characterized Panama's press scene as a roller coaster and Moscoso's administration as a "onetwo punch" where it seemed that one year more freedoms for the press were being granted, while the following year they were being taken away. In July of 2001 Reuters news service reported that the special Rapporteur for freedom of expression from the Organization of American States had concluded a five-day visit to Panama and found "notable" gains in freedom of expression in the country's 10-year-old democracy.

The Rapporteur noted that "democratic advances in Panama contributed notably to the development of freedom of expression." He praised the abolishment of longstanding gag measures limiting media freedom in 1999. He also expressed concern regarding the "anachronistic" contempt laws that remained on the books more than a decade after the 1989 U.S. invasion ended 21 years of military rule.

However, the OAS 2000 report characterized the Moscoso Administration's approach toward freedom of expression as a setback, while the previous report characterized the country as making progress in this area. One of the most onerous press laws was article 386, which allowed the attorney general of the country to impose prison sentences of up to eight days for attacks against honor. In several cases he filed suit under article 175 of Panama's Penal Code, which states, "Whoever publishes or reproduces, in any media, offences to an individual's good reputation shall be penalized with 18 to 24 months in prison." The regulation had its basis in the Panamanian constitution, which held that "public servants who exercise authority and jurisdiction … can pass sentences without due process … according to the law, and impose fines." [emphasis added]. The judiciary system in Panama appears neither independent nor necessarily fair. The involvement of the attorney general in defamation cases indicated that conflicts of interest were not taken into account when the courts reached their decisions.

Some of the more notorious censorship cases in the late 1990s involved Attorney General Sossa and the papers El Siglo and La Prensa . In June of 2001, the Technical Judicial Police raided the offices of the daily El Siglo with orders to arrest its editor, Carlos Singares. Sossa ordered the action after the publication of an article whose contents allegedly violated and offended his "dignity, honor, and decency."

On the same day as the raid, El Siglo published an article in which a lawyer accused Sossa of frequenting a Panama City brothel. Sossa said that Singares was to be arrested and imprisoned under article 386 for eight days. The Supreme Court overruled Singares's appeal and upheld the eight-days sentence.

This particular case caused concern among the press and international rights organizations. First, the decision ignored the fact that a lower court had not yet ruled on the veracity of the lawyer's allegations in the El Siglo article. Secondly, there were fears over the failure to enforce a separation of powers. In this case, Sossa, who allegedly suffered at the hands of Singares, held the ultimate power over whether Singares should serve the sentence.

Singares's problems with the state continued when in August of 2000 the Second Superior Tribunal of Justice upheld a 20-month prison sentence against him for having allegedly defamed former President Pérez Balla-dares in 1993. The prison sentence was commuted to a US $1,875 fine. In most defamation and libel cases, jail sentences have been commuted to fines.

CPJ highlighted a July 2000 decision made by the Tenth Criminal Court, which sentenced journalist Jean Marcel Chery, from the newspaper Panamá América , to 18 months of incarceration. The sentence stemmed from criminal defamation charges due to a 1996 article in El Siglo , in which he reported that a woman accused law enforcement personnel of stealing $33,000 worth of jewelry in the course of a raid on an apartment. The appeal to the conviction for criminal libel and sentence of 18 months in jail or a fine of $1,800 was pending at the end of 2001.

Also in July, President Moscoso enacted Law 38 to restrict access to information in the country. Article 70 of the law regulated access to public information and stipulated "information which may be confidential or restricted for reasons of public or special interest, cannot be distributed, as doing so could cause serious harm to society the state, or the individual in question." This protected information is broad in scope, as it could relate to "national security, someone's health, political opinions, legal status, sexual orientation, criminal records, bank accounts and other such data which are of a legal nature." The intention seems to be to prevent information from surfacing that would embarrass public officials.

Violence against journalists continued. In one case in October 2000, an editor and photojournalist from the Liberación daily in Lima, were assaulted during an interview. They were interviewing Jaime Alemán, a lawyer for Vladimir Montesinos, the former intelligence officer to President Fujimori of Peru. The attorney threatened the reporters when they arrived. They were then attacked by six individuals who wrestled the camera away from them. The camera was later returned to the journalists.

Sometimes the charges of slander and libel were filed and judged without the defendant even knowing. One such case occurred on February 18, 1999, when Judge Raul Olmos held a preliminary hearing on charges of slander and libel filed against José Otero of Panama's leading daily, La Prensa , even though the journalist had not been notified. The suit was filed by a dentist who was incorrectly identified as being on the Health Ministry list of professionals who relied on false diplomas to practice in the field.

La Prensa , Panama's leading daily, and its associate editor, Goritti, a Peruvian citizen, were the target of other defamation suits brought by the Panamanian government. President Pérez tried to deport the editor in 1997, after La Prensa reported that a drug trafficker had helped finance the president's campaign. The president backed down under international and domestic pressure. Gorriti and Rolado Rodriguez, a reporter for the paper, were charged on January 20, 1998, with "falsification of documents, refusal to disclose the source of a story, and libel" and ordered to stand trial for alleging that Panama's attorney general had accepted laundered drug money.

Another 1996 article stated that Sossa received a US $5,000 check from a Colombian drug trafficker as a donation to his campaign for re-election to the attorney general's post. Goritti and Rodriguez refused to reveal their source for that story. Panamanian law protected the confidentiality of journalists' sources. The editor Gorriti called the move "an affront by a blatantly abusive prosecutor's office to try to compel journalists to identify a confidential source."

In 1999, an organization called Comité por la Libertad de Expresión en Panamá (Panamanian Committee for Freedom of Expression) posted flyers of Gorriti around Panama City that read (rather ironically), "Get to know the assassin of press freedom in Panama." He was accused of being a foreign spy.

Many Panamanians resented the prize-winning journalist for his revealing and confrontational investigative reports. In 1997, President Pérez Balladeres's administration tried to keep him out of Panama, refusing the journalist's application for renewal of a one-year work permit and serving him with deportation orders. However, bowing to international pressure, the government reversed its decision.

The defamation campaign appeared to have started after La Prensa published a series of articles in 1999 stating the suspicious links between the Panamanian attorney general, two U.S. drug traffickers, a naturalized Panamanian, and a local lawyer. La Prensa reported that other Panamanian journalists were offered money to write negative articles about the paper. The attorney general accused La Prensa 's editor of waging "a campaign of loss of prestige and lies" against him. The Frente de Abogados Independientes (Independent Lawyers Association) branded the editor a marked person and asked him to leave Panama. The association even claimed that the editor "is more than journalist. He's an infiltrated agent disguised as a journalist."

In another defamation case, a columnist and radio journalist was charged with defaming former national police director during a February 4, 1998, broadcast of the news program TVN-Noticias . During the broadcast, Bernal blamed the police for the decapitation of four inmates at the Coiba Island prison.

On December 28, 1998, Panamanian police raided the offices of La Prensa and attempted to arrest Herasto Reyes, an investigative reporter, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. Journalists from around Panama City went to the newspaper's offices to stand in solidarity with Reyes. The police could not gain entry to the building as protesters blocked it. The police said they had orders to take Reyes to the prosecutors' office in connection with criminal defamation charges pending against him for defaming President Balladares in an August 1998 article in La Prensa . In the article, a former civilian member of Manuel Noriega's military dictatorship told Reyes that Pérez Balladares, who was a government official at the time, had tried to force him to cover up major financial woes. One of the results of La Prensa 's investigations into Sossa was that the Supreme Court urged that he be dismissed from his position.

Because of these existing cases against investigative journalists, in 2001 the Inter-American Committee on Human Rights recommended that the government change the existing legal process and place libel and slander under civil, rather than criminal, law. In September 2001 an OAS report on the status of freedom of speech in the hemisphere emphasized the repressive attitude of Panama's judicial system toward the media.

In July 2000, Bishop Romulo Emiliani left the Darien region following anonymous death threats; he had criticized publicly Colombian paramilitaries, guerrillas, and drug traffickers. He remained outside Panama. In 2000, there were at least 70 cases of journalists who had been accused of defamation under the criminal justice system. In March 2001, the president of the National Association of Journalists, the secretary general of the Journalists' Union, and the Editorial director of the daily newspaper El Panama America organized a protest in front of the Supreme Court to protest the Ministry of Justice's handling of freedom of speech issues. Over 100 journalists participated, maintaining that they were victims of harassment by the national government.

In 1998, Miguel Antonio Bernal, a respected journalist and human rights activists, challenged the constitutionality of the Penal Code provisions on which criminal defamation charges were based. The Supreme Court refused to hear his appeal.

Censorship

During the 1999 presidential election, authorities banned the publication of electoral results until technical data had been registered. The daily El Panamá América , for example, was fined US$10,000 because it did not comply in due time with this requirement. The same code also banned the publication of opinion polls ten days before elections.

Press censorship has even influenced publication of political poll results. On April 22, 1999, La Prensa printed an opinion poll that showed then-opposition candidate Mireya Moscoso leading for the first time in the race for the May 2 presidential elections. Twenty thousand copies of the paper were purchased en masse by supporters of the government party, who paid distributors more than the sale price in an effort to hinder circulation of that day's edition, according to the then-editor of La Prensa .

State-Press Relations

According to the U.S. Department of State, the government of Panama generally respected the human rights of its citizens in 2001. The media reported that problems continued to exist in several areas, however. The Panamanian National Police (PNP) were suspected in the deaths of two men. Abuse by prison guards was a persistent problem of the prison system, where overall conditions remained harsh, with occasional outbreaks of internal prison violence. Prolonged pretrial detention still existed as did arbitrary detentions. The criminal justice system was considered inefficient and subject to political manipulation. The media were subject to political pressure, libel suits, and punitive action by the government. Violence against women remained a serious problem. Women held some high positions in government, including the presidency; however, discrimination against women persisted. Discrimination also persisted against indigenous people, blacks, and ethnic minorities (such as Chinese). Worker rights were limited in export processing zones (also known as free trade zones). Both child labor and trafficking in persons were problems.

Some estimates concluded that one-third of journalists faced criminal defamation prosecutions. Self-censorship became rampant, and even protests provoked by media stories of government injustice and corruption during the military years became subdued.

Domestic and foreign journalists worked and traveled freely throughout the country. The law required directors and deputy directors of media outlets to be citizens. One case presented below concerned a world-renowned journalist, editor Gottori of La Prensa , was denounced by the Panamanian attorney general who tried to deport him, based in part on his citizenship status. Foreign journalists needed to receive one-year work permits to carry out reporting in Panama. The weekly La Cáscara news had been closed and the three employees denounced for slander and libel.

The newspapers and radio stations were subjected to various repressive governmental acts. For example, on March 16, 2001, Rainer Tuñón, former journalist at Crítica , and Juan Díaz, from Panamá América , were sentenced to 18 months in prison, which was commuted to a fine of US $400, for a "crime against honor" after they published information about a magistrate.

Beyond gag laws, the government continued to use other methods that resulted in media censorship. For example, the government restricted access to information sources that could allege or divulge state secrets. It also prohibited publishing certain news such as the identity of people involved in crimes.

The International Journalists' Network made clear, however, that in Panama there was a combative press, created by journalists dedicated to the advancement of the profession and social change. Consequently, there was in the early 2000s a boom in investigative journalism of high quality in this country, a positive step towards achieving the higher levels of media freedom.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

Foreigners may work in Panama on a one-year work permit, assuming there are no Panamanians available to fill the post. Rescinding work visas has been one way the national government has censored some members of the press.

Broadcast Media

In December 31, 1999, after 58 years, the U.S. military forces withdrew from Panama and the Panama Canal was passed to Panamanian control. As a result, the U.S. military broadcast, the Southern Command Network (SCN), ended its radio and television transmissions. The SCN had provided news, sports, and entertainment to millions of Panamanians and Americans, and gained attention when it remained on the air in December 1989 during the U.S. military invasion of Panama City.

Radio and television acquisition require the prior permission of a frequency for which the solicitor must meet a series of technical requirements that vary according to the place where the transmitters and signal strength are located.

On July 5, 1999, the Gaceta Oficial de Panamá published a new radio and television law, which in its Article 54 made licensing for the radio and television broadcasters more stringent, thus restricting the freedom of press.

After SCN disbanded, those frequencies that had been left without ownership were put up for auction. Later frequencies to be appropriated for commercial uses were the Ente Regulador de los Servicios Públicos

Several radio stations could be heard through the Internet or have links to their stations through the Internet. These included, among others, Estereo Panamá, La Mega, WAO 97.5. A variety of formats from traditional music to newscasts were provided, primarily in Spanish.

Four television stations were linked to the World Wide Web: FE TV Canal 5, RPC TV, Telemetro Panama, and TV Nacional Canal 2. Both RPC TV and Telemetro Panama had Real Player videos on their Internet sites.

Electronic News Media

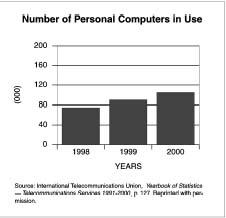

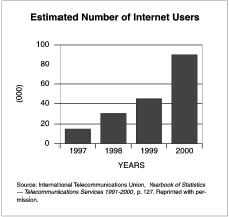

In the early 2000s, the use of personal computers and Internet was becoming available to more and more households considered to be in middle or high socioeconomic classes, as well as in schools, universities, and businesses.

There was no law that limited Internet access, and the majority of the newspapers and magazines in Panama had an electronic version. The news agency Panafax also had an Internet site, while the Panama Times was only accessed electronically. Panama News was an English language paper for the expatriate community, tourists, and Panamanians. It was considered a good source for rentals, housing, vacation tips, and related expatriate resources. Panamatravel was an Internet travel magazines about Panama, and many sites existed catering to expatriates living in Panama, business opportunities, and tourism promotion. It should also be noted that many

There were also various international news channels that had links to information about Panama on the Internet. HeraldLink Panama covered Panamanian news from the Miami Herald newspaper. In addition, Reuters/ Infoseek, BBC online, and the Internet service provider Yahoo! provided information about the country.

Education & Training

Article 40 of Panama's constitution stated that "every individual is free to practice any profession or office subject to the regulations established by the law toward morality, social provisions and security, licensing, public health, and obligatory unionization" [author's translation]. The journalist or broadcaster may also possess an equivalent degree from a foreign universities and revalidated at the University of Panama (Law 67 from 1978). They could work in Panama with a work visa.

However, Article 7 of Title II, of a law proposed on June 7, 2001, established that a professional journalist must be a "Panamanian citizen with a degree in journalism, communications, or information sciences, granted by an accredited university and recognized by the University of Panama and registered before the Ministry of Education in the Registration Book of Professional Journalists of the Republic of Panama" [author's translation].

Decree 189 of 1999 imposed mandatory licensing on radio and television newsreaders in Panama. The country's Public Services Regulatory Body announced that it would start cracking down on violators of the law. Sources at the Public Services Regulatory Body told CPJ the government had asked all broadcast media owners to submit a list of all their newsreaders by April 1, 2002. Radio stations faced fines of up to US $500 per day for each unlicensed newsreader that appeared on the air. Television stations could be fined up to US $25,000 per day for the same offense.

After Decree 189 was adopted, newsreader license requirements included attending a six-week seminar open to anyone who had completed at least four semesters of any university degree program. More than 2,000 licenses had been handed out under this system, according to official sources. In the early 2000s, newsreaders had either to hold a university degree in a relevant field or attend an eight-month course at the University of Panama. The course was set to begin around June 2002. The executive director of the CPJ stated that "A press licensing regime compromises freedom of expression by allowing a limited group to determine who can exercise this universal right and who cannot." In 1985, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruled that mandatory licensing of journalists violated the American Convention on Human Rights.

The issue of requiring licenses for reporters was a point of contention on the Panamanian press scene, as it was in many countries in the region. The Interamerican Press Agency cited its disagreement with the bill presented by the Panamanian Journalists Union. The law stated that only those with a university degree in communications could engage in journalism. The president of the Commission on Freedom of Press and Information of the IAPA said that this initiative was a step backwards in assuring the freedom of journalists by trying to regulate newspaper activity.

If approved, the law would create a Superior Council of Journalism that could impose "moral sanctions" on broadcasters, reporters, and anyone else that committed ethical infractions. Beyond that, the press would have as its purpose the publication of the truth, which would be controlled through a body comprised of journalists and members of government. If the information divulged was found to be false, the reporter would be obligated to publicly acknowledge the source. The council would comprise representatives from local press organizations and include at least one press union official. It would also require identification cards for local journalists and be in charge of accrediting foreign correspondents. The bill also proposed the legal limitation of foreign journalists working in a medium. Foreign journalists could join a staff only when national journalists could not fill a position.

The IAPA worried that if this law was approved, it could undermine the accomplishments of the gag law repeals in December 1999. This new bill did not respect the 10 basic freedoms of expression and freedom of the press acknowledged in the Declaration of Chapultepec. Additionally, it contradicted aspects of the Declaration of Rights on Freedom of Expression from the Inter-American Court on Human Rights. All of these documents rejected mandatory licensing of reporters and the obligation of revealing information sources.

The Consejo Supremo de Periodismo de Panamá (Supreme Council of Journalism in Panama) drafted the original text. The president of the Panamanian Commission of Communication and Transportation assured that Law 127 constituted a subsequent effort to eliminate the infamous gag laws. However, not everyone was satisfied with this new law. Interestingly, students from the Faculty of Communications at the University of Panama asked that the law to be vetoed since they considered it harmful to the job market.

Summary

Panama has been influenced by U.S. presence since the construction of the Panama Canal in the early twentieth century, as well as authoritarian regimes during the middle and latter parts. Press freedoms in Panama have been characterized as a roller coaster and President Moscoso's administration as a "one-two punch." Both of these descriptions came from the fact that the freedom of expression was guaranteed, but the government continued to enforce defamation and libel laws, otherwise known as gag laws. In Panama, contempt and defamation laws have been the favored methods of the state to coerce and pressure journalists. The country still maintained some regulations that were created under dictatorships and, at times, fortified these old laws with an array of new ones. As a consequence, journalists in Panama faced long-term imprisonment for writing articles that exposed the actions and behaviors of those in power, even though Panama was considered a democratic, market-oriented nation. Journalists were subject to licensing and could be jailed for up to two years for defamation. The attorney general still had the right to jail journalists for eight days with no trial if he found cause.

While investigative journalism was of high quality in Panama, it remained to be seen whether that strength would continue in the face of self-censorship and economic downturns that were affecting much of the print media in Latin America.

Bibliography

Committee to Protect Journalists. Attacks on the Press 2001. Panama. http://www.cpj.org/attacks01/americas01/panama.html ., 2002.

——. Panama: Authorities seek strict press licensing regime. http://www.cpj.org/news/2002/ , April 11, 2002. ———. Panama: Journalist goes on trial for defamation. http://www.cpj.org/news/2002 ., May 13, 2002.

——. The Americas 1999: Panama. http://www.cpj.org/attacks99/americas99/Panama.html ., 2002.

——. The Americas 2001: Panama. http://www.cpj.org/attacks01/ameircas01/panama.html ., 2002.

Fitzgerald, Mark. "Panama goes on press law 'reform'." Editor & Publisher, 132 (31): 6, 10, 1999.

Goodwin, Paul. Global Studies: Latin America, Peru. 10th ed. Storrs, CT: University of Connecticut, 2002.

Gorriti, Gustavo. "Tough journalism." New York Times, 146 (50897): A23, 1997.

International Journalists' Network. Country Profile-Panama. http://www.ijnet.org/Profile/LatinAmerica/Panama/media.html ., 2002.

——. "Aprueban ley de periodismo en Panamá." IJNet http://www.ijnet.org/Archive/2002 ., June 8, 2002.

——. "SIP rechaza proyecto de ley contra la prensa en Panamá." (April 23, 2002).

IPI World Press Freedom Review. Panama. www.freemedia.at/wpfr/panama.htm ., 2001, 2000, 1999, 1998.

"Panamanian Insults" (August 21, 2000). Editor & Publisher, 133 (34): 16-19, August 21, 2000.

U.S. Department of State. Country Reports on Human Rights Practices—2001, Panama. http://www.state.gov , 2002.

Cynthia K. Pope

Thank You!

Sincerely,

Micci