Peru

Basic Data

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Peru |

| Region (Map name): | South America |

| Population: | 27,483,864 |

| Language(s): | Spanish (official),Quechua (official),Aymara |

| Literacy rate: | 88.7% |

| Area: | 1,285,220 sq km |

| GDP: | 53,466 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Daily Newspapers: | 57 |

| Total Circulation: | 5,700,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 342 |

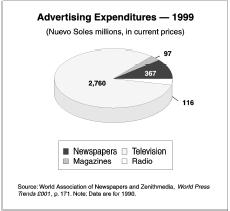

| Total Newspaper Ad Receipts: | 367 (Nuevo Soles millions) |

| As % of All Ad Expenditures: | 11.00 |

| Number of Television Stations: | 13 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 3,060,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 111.3 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 349,520 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 13.6 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 859 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 6,650,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 242.0 |

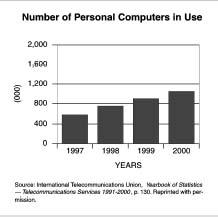

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 1,050,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 38.2 |

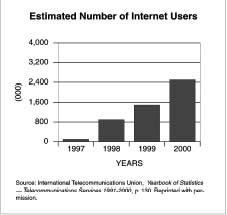

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 2,500,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 91.0 |

Background & General Characteristics

Like neighboring countries Bolivia and Ecuador, Peru has a large population of indigenous citizens. In fact, in the early 2000s, 45 percent of the population of 27 million was considered indigenous, and many of these spoke Quechua or Aymara. Both Spanish and Quechua were the official languages, although newspapers were published primarily in Spanish. Thirty-seven percent of the population was classified as mestizo (a mixture of European and indigenous blood), 15 percent was white, while the remaining percentage was comprised of other backgrounds, including a strong Japanese influence. This influence was most notably seen during the presidency of Alberto Fuji-mori during the 1990s. The adult literacy rate was approximately 89 percent with a life expectancy of 68 years (male) and 73 years (female). Education was compulsory from six to eleven years of age.

Peru is considered a democratic republic with a multi-party political system. Lima, the capital, lies on the Pacific coast and is the bureaucratic heart of Peru, although it would be appropriate to say that the country's heart lies in the traditionally indigenous territories of the Andes. Centuries, as well as mountains, divide populations throughout this country. Very few city dwellers know either Quechua or Aymara, the indigenous languages spoken daily by millions of Peruvians.

This lack of knowledge about the languages and cultures of the indigenous populations has led to many historically unsuccessful development programs administered by Lima to alleviate poverty in the countryside. The Positivists, for example, sought in vain in the 1920s to Europeanize indigenous groups. On the other hand, other reformers sought to identify with the indigenous peoples. For example, the popular political ideology, Aprismo , embraced the idea of an alliance of Indoamerican territories to recover the Americas for their original inhabitants.

Government in the 1960s and 1970s carried out some of the recommendations, such as agrarian reform, which affected the political and social milieu of current times. During the 1960s peasants invaded large haciendas (farms) demanding that the owners return their property to the indigenous inhabitants. Against this background of rural violence, the Peruvian military seized power in 1968. The left-leaning military regime expropriated all the daily newspapers in the capital city of Lima and assigned each one to one of the country's social forces, such as labor unions and intellectuals.

Many newspapers protested the expropriation by the military. Only one paper, El Comercio , supported the new military regime. This paper was one of the oldest and most prestigious newspapers in Latin America, founded in Lima in 1839. The military closed down two of the most popular newspapers and one radio station for 16 days. Authorities arrested and deported journalists and foreign correspondents critical of their policies and repeatedly closed down the magazine Caretas . Newspaper owners demanded that the government explain the motives behind its censorship and harassment of the mass media.

In the late 1960s the military government issued a Statute of Press Freedom, which was generally supported by journalists and attacked by newspaper owners. The statute restricted ownership to native Peruvians; recognized journalism as a profession; regulated the right of reply; and identified and established penalties for the crimes of libel and slander. The press's right to criticize the government was granted as long as various ideas were upheld: respect for the law, truth and morality, the demands of national security and defense, and personal and family honor and privacy.

The military government stepped down in 1980 amid a variety of social problems and population pressure. Civilian rule, however, did not necessarily equal democracy for Peru. The left-wing guerrilla organizations, Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path) and the Tupac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (MRTA), used violence and terrorism against the government, military, and even villagers to reach their stated goals of social justice. Because of the threat, the government declared repeated states of emergency and lifted civil guarantees throughout the 1980s.

Alberto Fujimori was elected democratically during the years of the 1989 reform laws, reflecting a growing will to debureaucratize Peru. However, Fujimori staged an autogolpe (self-coup) in 1992 when Congress hesitated to enact economic and political reforms. He suspended the constitution, arrested a number of opposition leaders, shut down Congress, and openly challenged the power of the judiciary. In 1993, in true dictatorial fashion, he created a constitutional amendment that allowed him to run for a second consecutive term.

Even though Fujimori took a repressive stance on opposition and made what appeared to be a crackdown on the press, the Peruvian population re-elected him in 1995. This was probably due to his successful economic policies, which led to a 12 percent growth in the Peruvian economy, the highest in the world for 1994, and the campaign against terrorist organizations. His authoritarian side continued to grow during this time, however, and culminated with a fraudulent election in 2000. Despite a constitutional prohibition against running for three consecutive terms, Fujimori decided to run again in April 2000. Shortly thereafter, Fujimori was forced to resign amid allegations of a fraudulent election, press censorship, massive corruption, human rights abuses, and violence. He resigned as president in November 2000 in a fax sent from Japan, where he chose to remain.

The press represented a wide spectrum of opinion including those in favor of and in opposition to the government. Peru's weekly newsmagazines were the most aggressive of any in the Andean region. In the Lima area alone, there were 20 daily newspapers, 7 television stations, approximately 65 radio stations, and 2 news channels on 2 commercial cable systems. There were numerous provincial newspapers and radio stations. All were privately owned except for one government-owned daily newspaper, one government-owned television network, and two government-owned radio stations, none of which had a particularly large audience, according to the United States Department of State.

In the 1990s in Peru, independent journalists played a critical role in bringing down the Fujimori government, often characterized as corrupt and authoritarian. The daily newspaper El Comercio , the newspaper with the highest distribution, and La República , as well as the magazine Caretas could be included in this group of independent publications. Their professionalism and social critique were cited by the Interamerican Press Agency, which honored them with the freedom of expression award for their emblematic labor during difficult times.

Other newspapers included Correo Perú , El Tiempo , Gestión , La EncuestaLa IndustriaLiberoOjo , and Todo Sport . Lima Post was an English language newspaper. As far as the "governmental" press, it is important to highlight the official newspaper El Peruano and Expreso , whose ex-editor, Eduardo Calmell del Solar, was placed under house arrest for participating in cases of corruption. La Prensa , one of the most respected newspapers in Latin America, folded during the 1980s as pressure for modernization in the computer age began to take is toll on papers with marginal financial situations.

Economic Framework

Alejandro Toledo was voted in during a new election in June 2001. He was a Stanford-trained economist and has advised the World Bank. Toledo said he intended to eliminate corruption, reform the judiciary, refashion the Fujimori-inspired constitution of 1993, restore freedom of the press and speech, and hold elements in the military accountable for their transgressions. He encouraged the infusion of foreign investments, resumed a policy of privatization, and engaged in renegotiating outstanding agreements with the International Monetary Fund.

Press Laws

The Constitution provided for freedom of speech and of the press, and, unlike in earlier years, the government generally respected this right in practice; however, some problems remained. The government generally tolerated criticism and did not seek to restrict press freedoms. However, fear of legal proceedings and strong popular opinion discouraged public expressions of pro-Fujimori sentiments in the media, the opposite ideological stance from the 1990s when Fujimori was in power.

In December 2001 the Toledo administration proposed the Law of Modernization and Transparency of Telecommunications Services, which a congressional subcommittee took under consideration. The bill would create a radio and television commission, comprising government and civil society representatives, to oversee and review the TV licensing process.

In 2001 the Ley Orgánica de Elecciones (Election Law) was declared unconstitutional. This law had prohibited the publication of unofficial election results from 4 p.m. until a maximum of six hours from the close of the polls.

Libel was a criminal offense and cases were brought frequently by individuals, including political figures, against journalists. One journalist from the political program Entre Lineas concluded that former president Alan García obtained an intelligence officer's help to make the judiciary decide the prescription of García's crimes so that García could return to the country and run in the last presidential elections. García accused Valenzuela of libel, a process that continued into 2002.

Other libel and defamation suits were filed against journalists. Manuel Ulloa filed a $1 million lawsuit for libel and defamation against the opposition newspaper Liberación , which led to the seizure of the paper's printing press. Also, a former pro-Fujimori congressman, Miguel Ciccia, filed a libel and defamation suite against Editora Correo.

In February 2001 the Inter-American Press Association (IAPA) awarded the Chapultepec Grand Prize to former Human Rights Ombudsman Jorge Santiestevan for his support of freedom of expression in Peru. The Declaration of Chapultepec (Mexico City, 1994) set forth 10 principles on freedom of the press and expression. The IAPA also met with President Paniagua, members of Congress, and Supreme Court justices in an open forum with journalism and law students to discuss issues of press freedom.

The IPI Executive Board unanimously agreed on January 26, 2001, to remove Peru from the "IPI Watch List," a document that places on notice countries that appear to be moving towards suppression or restriction of press freedom. The reason for this action included the return of the television station, Frecuencia Latina-Canal 2 , to the Israeli-born businessman Baruch Ivcher, who had been

The IPI Board also noted that the cases of five other journalists, who were serving sentences from 12 to 20 years imprisonment for "terrorism" or "betrayal of the state," were under review by the Ministry of Justice's new National Human Rights Council. Some of these journalists were still imprisoned as of 2002.

Despite more press freedom in 2001, journalists still faced threats, attacks, and legal harassment, particularly at the hands of public officials in the country's interior. Both government forces and terrorist organizations attacked the press. Members of the Frente Patriótico de Loreto (Loreto Patriotic Front, FPL) physically and verbally attacked journalists in the Iquitos area. FPL also threatened to destroy the Channel 6 television studios if the cable station continued to employ journalists whom they accused of being Fujimori supporters. The television station's owner was forced to fire the journalists. FPL's supporters also attacked the studio of La Karibena radio station in Iquitos. The studio suffered damages, and one of the radio station's employees received death threats. In the first incident, the FPL members threw rocks after they saw posters of a certain presidential candidate. They threatened to return and burn down the radio station if the posters were not taken down. The second time the assailants destroyed the building's windows, painted its walls black, and tried to enter the studios. Government sympathizers accused journalists of printing untrue information. The reporters were eventually acquitted by a judge who ruled that they were simply exercising their right to impart information of public interest.

Another incident occurred when Peru's Channel 2 news station was blown up in a terrorist attack. Fuji-mori's outrage over Ivcher began when Channel 2 aired in August 1996 a report linking drug traffickers to the Peruvian army. After the broadcast, the military withdrew the soldiers who had provided street security for Frecuencia Latina from the Shining Path guerrillas. In yet another instance, a story aired about "Plan Emilio," an illegal intelligence operation involving electronic surveillance of opposition politicians and journalists during Fujimori's reign. After the story, the Peruvian police raided the station. They were enforcing a court order to strip station-owner Baruch Ivcher, born in Israel, of his Peruvian citizenship and turn control of the station, Frecuencia Latina , over to a pair of minority investors. Quijandria, the host of a popular news show called Contrapunto (Counterpoint), resigned in protest. Peru's Joint Command issued a press release declaring that Ivcher had mounted "a campaign intended to damage the image and prestige of Peru's armed forces." However, under Peru's constitution, the military was barred from publicly expressing opinions on political matters.

On July 13, 1996, Contrapunto aired conversations taped by government security forces that were spying on journalists. The same day the immigration office issued its decree invalidating Ivcher's Peruvian citizenship. Under Peruvian law, noncitizens could not own media outlets. Peruvians demonstrated their support by marching in front of the station. The station, Channel 2, was surrounded by twenty-foot-high cement walls with guard towers and three-inch-thick steel security doors. The journalists resigned. Government officials claimed that the decision to transfer ownership of the station had nothing to do with press freedom. A congressman claimed that it was an issue of national security.

Another dark stage for the press during Fujimori's presidency was characterized by the Vladivideos (video-tapes recorded of bribes being paid to key media figures by Vladimiro Montesinos, Fujimori's intelligence adviser). These tapes confirmed that the Fujimori regime paid five of the six commercial television stations, much of the tabloid press, and at least one major newspaper to print pro-Fujimori articles and editorials. In a video released in February 2001 Montesinos bragged: "[The broadcast channels] are all lined up. Every day I have a meeting with them and we plan what is going to come out in the nightly news shows" (Committee to Protect Journalists, 2002). One of these videos illustrated that Montesinos and Fujimori colluded with television channel owners to ensure Fujimori's third presidential term in April 2000.

One of the owners of Channel 4 admitted to having received US $9 million from Montesinos in exchange for free rein to dictate Channel 4's programming content to favor Fujimori's candidacy. The station's owners became fugitives. Another video showed businessman Delgado Parker, former owner of Red Global de Televisión-Canal 13 , negotiating with Montesinos the 1999 dismissal of a Fujimori critic in exchange for Montesinos's support in several legal disputes over the station's ownership.

In addition to bribes, the corrupt tactics included judicial persecution, manipulation of government advertising, threats, and tax incentives.

The defamation campaign that the Fujimori government orchestrated against the independent press and the opposition from 1998 to 2000 was further exposed in 2001. The prensa chica (a group of tabloids that published unsubstantiated allegations about independent journalists and opposition politicians) carried out the campaign. In March 2001, a judge prohibited several tabloid owners from leaving the country after a public prose-cutor's investigation revealed evidence that the government had directly bankrolled the tabloids. A national debate over corruption and media took place in 2001 with the Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa proposing to empower the judiciary to revoke the licenses of TV stations that had supported Fujimori.

State-Press Relations

The departure of Fujimori led to a freer and more independent print and broadcast media in Peru, unlike the years during which independent journalists were subjected to a systematic campaign of persecution. After Fuji-mori, the media in Peru experienced a primavera democrática (democratic spring), which echoed throughout the society in general. The government no longer censored books, publications, films, or plays, and did not limit access to the Internet. The government did not restrict academic freedom during 2001. By the end of 2001 a congressional committee debated a new Telecommunications Law, which proposed the creation of a media regulatory commission.

In 2002, governed by Alejandro Toledo, Peru continued to suffer the consequences of almost 10 years of repression imposed by Fujimori. Public confidence in the media, particularly television, had been undermined by news about the depth of media corruption during the Fuji-mori regime. Rebuilding a democratic society was the new primary goal facing Peru. On July 5, 2001, the Peruvian Congress approved the creation of a Truth Commission, in charge of judging cases of human rights violations for crimes committed during the last 20 years of the twentieth century.

Newspapers, television, and radio were becoming increasingly important in the democratization project. The independent press was comprised of journalists known for their high quality and tenacious exercise of freedom of expression, even in the face of on-and-off repression that had included temporary suspensions and even jail time. Congressional committees under the Toledo administration filed criminal complaints against media figures, but even more disconcerting was the idea that fear encouraged self-censorship by journalists wary of drawing unwelcome government attention.

Broadcast Media

The Texto Unico Ordenado de la Ley de Telecomunicaciones (national telecommunications law), published on May 15, 1993, stated that the development and regulation of telecommunications should take place within the framework of a free market economy and that every person had the right to use and loan telecommunication services.

The Peruvian Code of Radio Ethics, approved on July 15, 1994, stated that "the diffusion of private radio is based on freedom, free market and competition, and in its own self control, within a democratic framework." Radio Programas del Perú was the most important private national radio station in the country. One media family in Peru, the Delgado Parkers, established regional networks for radio and television called Sociedad Latinoamericana de Radiodifusión (SOLAR) and Sistema Unido de Retransmición (SUR), respectively.

In the early 2000s, however, television was the most popular media source in Peru, as it reached 80 percent of the population. The leading company in the Peruvian communications sector was América Televisión , which owned channels 5 and 2.

Electronic News Media

In the early 2000s, the Internet was not censored in Peru and was gaining in popularity throughout the country. Like the rest of Latin America, the Internet was becoming increasingly popular with 10 service providers as of the year 2000. Few people connected to it from their homes, however, since the connection fee was still very expensive for a country in which almost half the population lived in poverty.

To counteract expensive connection fees, Internet kiosks were located throughout Lima. Using these Internet stations for one hour was equivalent to the cost of a postage stamp in the United States. Because of the low cost, many Peruvians preferred to utilize this medium to communicate with family and friends living abroad instead of connecting from home.

Education & Training

In 2002, it was not mandatory for journalists or broadcasters to have a license to practice or a university

The Peruvian Congress passed Law Number 26937 on March 12, 1998, that established that Article 2, Part 4 of the Constitution guaranteed the right to freedom of expression and thought (and thus the freedom to state those ideas), subject to the existing constitutional norms.

Summary

In the early 2000s, Peru was in the throes of debureaucratization, anti-terrorism, and pro-democratization movements. It appeared that the Toledo administration had ushered in an era of hope for journalists, reporters, and newsreaders for practicing their professions in relative freedom. The relationship between the government and press appeared to have left behind the former disagreements and threats, but it was unclear if Toledo would continue with his democratic ideals.

Despite the marked improvement in press freedom conditions in 2001, some attacks and threats against journalists continued, particularly in rural areas. It would be difficult for Peru to overcome the corruption and authoritarianism of the military and Fujimori regimes, but various sources seemed to be optimistic about the role of the press being able to bring about positive social change in that country.

Bibliography

Chauvin, Lucien. "Peru probe touches media, shops." Advertising Age , 72 no. 9 (2001): 24-28.

Cole, Richard R., ed. Communication in Latin America: Journalism, Mass Media, and Society . Wilmington, Delaware: Scholarly Resources, Inc., 1996.

Committee to Protect Journalists. Attacks on the Press 2001—Peru , 2002. Available at http://www.cpj.org/attacks01.americas01/peru.html .

Gargúrevich, Juan, and Elizabeth Fox. "Revolution and the Press in Peru," Media and Politics in Latin America . Ed. Elizabeth Fox. London: Sage Publications, 1988.

Goodwin, Paul. Global Studies: Latin America, Peru . 10th ed. Storrs, CT: University of Connecticut, 2002.

Guillermoprieto, Alma. The Heart That Bleeds: Latin America Now . New York: Vintage Books, 1994.

International Journalists' Network (IJNet). Peru: Press Overview , 2001. Available at http://www.ijnet.org/Profile/LatinAmerica/Peru .

IPI World Press Freedom Review. Peru. www.freemedia.at/wpfr/peru.htm ., 2001.

Johnston, Carla Brooks. Global News Access . Westport, CT: Praeger, 1998.

Simon, Joel. "Fujimori stomps a station," Columbia Journalism Review 36, no.4 (1997): 58-60.

U.S. Department of State. Country Reports on Human Rights Practices—2001. Uruguay 2002. Available at http://www.state.gov/ .

Cynthia K. Pope