Serbia and Montenegro

Basic Data

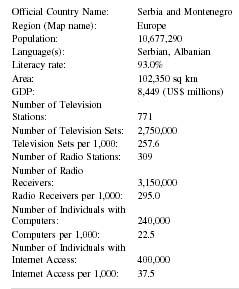

| Official Country Name: | Serbia and Montenegro |

| Region (Map name): | Europe |

| Population: | 10,677,290 |

| Language(s): | Serbian, Albanian |

| Literacy rate: | 93.0% |

| Area: | 102,350 sq km |

| GDP: | 8,449 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Television Stations: | 771 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 2,750,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 257.6 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 309 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 3,150,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 295.0 |

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 240,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 22.5 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 400,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 37.5 |

Background & General Characteristics

Yugoslavia was born the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes on December 1, 1918. The Federal Republic of Yugoslavia disintegrated into the independent constituent republics of Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, Macedonia, and Yugoslavia in 1991. On March 14, 2002, Yugoslavia ceased to exist. What remained of Yugoslavia emerged as the Federal Republic of Serbia and Montenegro. Within three years of that date, Montenegro will decide whether or not to seek complete independence. The Serbian province of Kosovo, with an Albanian majority, threatens to secede from Serbia. What remains of modern Serbia could be much less in territory than Serbia's pre-1914 boundaries.

Serbia's history dates to the early history of the Balkan Peninsula. From the eighth to the eleventh centuries, either the Bulgars or the Byzantine Empire controlled the Serbs.

Modern Serbia's sister republic, Montenegro, was incorporated into the first Serbian kingdom during the Middle Ages. Montenegro (or Black Mountain) successfully remained independent of the Ottoman Turks even though Serbia was conquered.

The Paris peace treaties ending World War I accepted the emergence of a south Slav state. Roman Catholic Slovenes and Croats were merged with Eastern Orthodox Serbs, Montenegrins, and Muslim Albanians. The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes was renamed Yugoslavia (South Slavs) in 1929. In the twentieth century three men, King Alexander II, Marshal Josip Tito, and Serbian Communist Party leader Slobodan Milosevic respectively gave birth to, shaped, and destroyed modern Yugoslavia.

The first Serbian newspapers were published in Kragujevac and in Novi Sad: they were Novine Serbske (1834) and Vestnik (1848) respectively. Serbia's first daily newspaper was published in Novi Sad, the Srbski Dvenik (1852). Montenegro's first newspaper was Crnogorac (1871). Prizren (1880) was Kosovo's first newspaper. The number of newspapers in Serbia increased after the promulgation of the 1889 Constitution granting freedom of the press. Obrenovic King Alexander suspended Serbi's press freedom in 1893. Under Peter I (1903-1921) the 1889 Constitution was replaced with the Constitution of 1903, which restored freedom of the press. In 1905, 20 daily were published in Belgrade, but by 1910 the number of print media numbered over 775 publications.

After World War I the newly created Yugoslavia was given a new constitution in 1920. The Constitution of 1920 was in essence the Serbian Constitution of 1903, expanded to include Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia but not in a federal union of states. Serbia remained the dominant power in the governmental structure and in the Parliament that centralized power in Belgrade. Parliamentary representation and religious freedom were written into the Constitution. In spite of the Constitution's failure to offer adequate protection for individual rights, speech, press, and public meetings, new print media quickly surfaced, spreading rumors about the rise of Communism and revolution. Yugoslavia's new Parliament responded by issuing a decree banning all print media published by the Communist press, including the newspapers Boda and Kommunist . Radical Party print media continued to publish. Other major Yugoslav political party newspapers included Rec for the Independent Democratic Party and the Croatian Republican Peasant Party's newspaper Slobodnidom . An estimate of the number of print media in Yugoslavia between the World Wars varies from over six hundred to over eleven hundred publications. Yugoslavi's first news agency Avila .

The political instability between Yugoslavia's competing political, religious, and ethnic groups forced King Alexander II to suspend the 1920 Constitution in 1929 and declare a royal dictatorship. The public accepted the political change with blame initially placed on the politicians and the press. The press was perceived as having abused its rights, and its members were placed under police control. Any newspaper expressing a distasteful opinion was confiscated. Editors had to confine themselves to reporting the news. All opinions were submitted to the government for review. Acts of terrorism, sedition, or the dissemination of Communist propaganda were punished with either the death penalty or a long prison sentence. Freedom of the press was eliminated. Political parties based on a regional or religious basis were declared illegal. The king assumed the power to remove judges. Yugoslavia became a virtually one-party state. The press was effectively muzzled.

The royal dictatorship ended when Alexander II was assassinated in Marseilles, France, during a state visit in 1934. The late king's cousin, Paul, governed Yugoslavia as regent until Alexander's eldest son, Peter II, came of age in 1941. During the regency Yugoslavia published 50 daily newspapers. Most had small circulations. The major Serbian dailies were Politika , Vreme , and Pravada . Many of Alexander's controversial policies continued, including the banning of political parties. Constitutional reform in Yugoslavia was stalemated over whether or not to give Croatia autonomy. When an agreement was reached on Croatian autonomy, the Slovenes and Serbs vigorously protested because they were still ruled from Belgrade. As the signs of another war grew larger, Yugoslavia found itself more financially dependent on a resurgent Germany. In an attempt to maintain Yugoslav neutrality, Prince Regent Paul signed an alliance with Hitler's Germany. A mutiny within the Yugoslav military against the German alliance forced the Regent from power, and 17-year-old Peter II was proclaimed of age. Peter II reigned less than two weeks before fleeing Yugoslavia to escape the advancing German military. Yugoslavia quickly surrendered and was reduced in size, with regions given to Italy, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Italian-controlled Albania. Independent republics under Italian control were created in Montenegro and Croatia. What was left of Yugoslavia was divided between Italy and Germany.

During World War II King Peter II maintained a government-in-exile in Great Britain. Within Yugoslavia two antifascist organizations emerged fighting the Germans and Italians, the Chetniks under General Draza Mihailovic and the Partisans under Josif Tito. The Chetniks were anti-Communist and supported the king. The Partisans were pro-Communist and directed from Moscow. Borba , long suppressed under royal orders, emerged as the official newspaper for the Partisans. Belgrade's liberation in 1944 restored many of Yugoslavia's print media to active publication, among them Politika . The majority of publications were pro-Communist. Yugoslavia's future was determined by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who gave British support to Tito and the Communists, believing that Mihailovic's Chetniks had not been sufficiently antifascist during the war. In 1945 the monarchy was dissolved in a rigged vote. Yugoslavia became a Communist state.

Under Communist rule Yugoslavia was divided into six republics, Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia, Montenegro, and Macedonia, and the Serbian autonomous provinces of Kosovo and Vojvodina. Under the new Federal People's Republic Constitution, private ownership of the media and business was ended. Press organizations were nationalized along with printing houses, paper mills, and radio transmitters. The press was placed under the Ministry of Information and served as a propaganda tool of the Communist state. A 1946 press law limited the right of political parties to publish, but allowed the government to supply newsprint, equipment, and other materials to the print media. Any publication encouraging revolt, spreading false information, and the threat to harm the socialist state was to be closed and the authors punished. When Tito broke with Moscow in 1948, some of the harsher aspects of press restrictions were loosened. The Communist party in Yugoslavia oversaw the print and broadcast media, but after 1948 allowed more latitude in what was published and broadcast. During the Tito regime it was estimated that Yugoslavia published over 2,500 newspapers and 1,500 periodicals. Each republic and autonomous province was allowed the right to print its own newspapers and have its own broadcast stations. Yugoslavia's newspapers with the largest circulation during the Communist era were the Belgrade-published Vecernje Novosti , PolitikaPolitika Ekspres , and Sport . Major Croatian-published newspapers were Vecernjji List , Sportske Novosti , and Vjesnik . Other major Yugoslav newspapers included the Slovenian Delo , the Bosnian Oslobodenje , and the Dalmatian Slobodna Dalmatija .

In 1974 Yugoslavia adopted a new constitution, which guaranteed freedom and the rights of man and citizens, limited only by the equal freedom and rights of others and the community. The criminal code allowed the punishment of counterrevolutionary activity (Article 114), for hostile propaganda (Article 118), and association to promote hostile activity (Article 136). The 1974 Law on the Cinema banned films whose human, cultural, and educational aims were contrary to a socialist state. Some argue that freedom of expression was evident in Tito's Yugoslavia, as long as it did not enter print or was broadcast. In the 1970s student newspapers were the print media most often denied the right to publish by government decree. In the late 1980s the newspapers of Slovenia challenged Yugoslavia's conventional media norms about self-censorship and published discussions about the future of the Yugoslav and Slovenian republics, and interviews with former Communist official and exiled writer Milovan Djilas. By 1987 Yugoslavia had 2,825 newspapers with a circulation of 2.7 million. Only five newspapers had a circulation of over 100,000, among them, Borba , printed in both Latin and Cyrillic script, and Politika , printed in Cyrillic, but primarily a Belgrade newspaper. Yugoslavia's major newspapers published under the influence and guidance of the pro-Communist Socialist Alliance and the Association of Journalists. Self-censorship was the norm.

In 1987 changes were underway, as Serbia came under the increasing authoritarian nationalism of Serbia Communist Party chief Slobodan Milosevic, first as the president of Serbia (1989-1997) and later as the president of Yugoslavia (1997-2000). TV Belgrade installed its own news network in Kosovo rather than rely on Kosovo's television station. Newspaper editors for Duga , NIN , IntervjuPolitika , and Svet were replaced on Milosevic's orders. The increasing cost of print media forced Yugoslavs to turn to electronic media for information. Federal Yugoslav media by 1989 included only Borba and Tanjung (news agency). In 1990 Croatia established its own state media. In the same year a new press law abolished press censorship and permitted private ownership of the press and the right of foreign journalists to enter Yugoslavia. As each Yugoslav republic severed ties with Belgrade, new constitutions offered press and speech freedoms except in Serbia. With Tito's death in 1980, it was clear that the republics of Yugoslavia lacked sufficient reasons to stay united in a federal state. Centuries of cultural, ethnic, and religious differences were not resolved during the royal dictatorship of Alexander II or the Communist rule of Marshal Tito. The institution of monarchy might have served as a unifying force for Yugoslavia's diverse populations except for the fact that Tito had discredited it, and Yugoslavia's last king, Peter II, died in exile at 49 in less than dignified circumstances. Peter II's son, Crown Prince Alexander, resided in London and seemed undecided about his role in a rapidly changing Yugoslavia.

In Milosevic controlled Serbia, Belgrade denied frequency broadcast rights to television and radio stations. High licensing fees forced many broadcast media to close or forced new entrants to reconsider. The high cost of print media allowed the Milosevic controlled airwaves to spread propaganda by appealing to Serbian national interests. Attempts to close anti-Milosevic newspapers witnessed the emergence of new newspapers to counter government influence and regulation. The NATO intervention in Bosnia and Kosovo, and NATO's destructive bombing of Serbia ultimately contributed to Milosevic's downfall. Milosevic's election defeat to Vojislav Kostunica in 2000 was a shock to the president of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. This time Milosevic misunderstood the will of the Yugoslav people. Kostunica's assumption of the Federal Yugoslav presidency provided the opportunity to restructure the remaining Yugoslav republics and autonomous provinces within the context of a multiparty democracy. The desire of Montenegro to declare its independence was discouraged by the United States and the European Union, once Milosevic was gone from power and transported to The Hague for trial as a war criminal.

Based on the March 14, 2002, accord signed by representatives of the Yugoslav republics of Serbia and Montenegro, the two republics are semi-independent states that share a common defense and foreign policy but maintain separate economies, currencies, and customs services. Serbia's population is over 10 million people, while Montenegro's population numbers only 650,000 citizens. Serbia and Montenegro will jointly share the United Nations seat of the former Yugoslavia with their United Nation's representative alternatively between a Serb and a Montenegrin. Serbia has two autonomous provinces, Kosovo in the southwest and Vojvodina in the north.

The Federal Republic of Serbia and Montenegro share a chief of state, prime minister, cabinet, and a court. Article 36 of Yugoslavia's Constitution guarantees freedom of the press and other forms of public information. Citizens have the right to express and publish their opinions in the mass media. The publication of newspapers and public dissemination of information by other media shall be accessible to all, without prior approval, after registration with the competent authorities. Radio and television stations shall be set up in accordance with the law. Under Article 37 the right to publish false information, which violates someone's rights or interests must be corrected with damage compensation and entitlement. The right to reply in the public media is guaranteed. Article 38 prohibits censorship of the press and other forms of public information. No one may prevent the distribution of the press or dissemination of other publications, unless it has been determined by a court decision that they call for the violent overthrow of the constitutional order or violation of the territorial integrity of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, violate the guaranteed rights and liberties of man and the citizen, or foment national, racial, or religious intolerance and hatred. Freedom of speech and public appearance is guaranteed in Article 39. A citizen's right to publicly criticize the work of the government and other agencies and officials, to submit representations, petitions, and proposals, and receive an answer is guaranteed in Article 44. Article 45 offers freedom of expression of national sentiments and culture, and the use of one's mother tongue.

The existing bicameral federal assembly ( Savezna Skupstina ) consists of a Chamber of Republics with 40 seats evenly divided between Serbs and Montenegrins serving four-year terms. The lower house or Chamber of Deputies has 138 seats with 108 allocated to Serbs and 30 to Montenegrins. Under the 2002 arrangement the Savezna Skupstina will be replaced with a unicameral legislature. A president of Serbia and Montenegro will be chosen by the Parliament of Serbia and Montenegro who will propose a council of ministers of five: foreign affairs, defense, international economic affairs, internal economic affairs, and protection of human and minority rights. A Court of Serbia and Montenegro has constitutional and judicial functions reviewing the actions of the Council of Ministers and bringing the judicial systems into accord. In addition to the federal assembly, each republic has its own president, prime minister, and popularly elected legislature.

There are over 2,650 publications in the Federal Republic of Serbia and Montenegro—2,511 in Serbia and 165 in Montenegro. Daily newspapers printed in Serbia (with 1995 circulations in parentheses) are the Federal/ Serbian daily Borba (85,000) and the Serbian morning dailies Narodne Novine (7,000), Politika (260,000), Politika Ekspres (130,000), and Privredni Pregled (7,000). Vcernje Novosti (300,000) is an evening daily published in Serbia. Koha is an Albanian language morning daily with a circulation of 4,000. The Hungarian language daily Magyar Szo has a circulation of 12,500. Four newspapers are associated with political parties, Srpska Rec (Serbian Renewal Movement), Velika Srbija and Istok (Serbian Radical Party), and Bujku (Democratic Alliance of Kosovo). Politika , Ekspres , and Novosti are considered close to the government but are frequent critics of it. During the Milosevic era the newspapers Borba , Jedinstvo , Dnevnik , and Pobjeda were considered to be under the direct influence of the Communist government. Montenegro's leading newspaper is Pobjeda with a circulation of 25,000.

Major general interest periodicals all published in Serbia (with 1995 circulations in parentheses) are the fortnightlies Duga (160,000) and Srpska Rec (19,000),and the weeklies Intervju (25,000), Nin (35,000), and Vreme (35,000). Montenegro's major general interest periodical is Monitor (7,000). Special interest periodicals are the fortnightly women's magazine Bazar (60,000), the weeklies Ekonomska Politika (8,000), Illustrovanna Politika (65,000), and the children's publication Politikin Zabavnik (40,000). The Journalists Federation publishes the fortnightly magazine Madjunarodna Politika (3,000). The International Economic Institute publishes the quarterly Medjunarodni Problemi (1,000). The labor publication Rad (10,000) is published monthly. The Tanjung News Agency publishes the monthly Yugoslav Life (30,000). The bimonthly illustrated Vojska has a circulation of 50,000, and the biweekly student published magazine Student has 10,000 readers. Additional weekly periodicals include Nedeljni Telegraf , IntervjuSvedok , Svet , ProfilStudentDT PecatPolisLiberalOnogost Standard , ArgumentNovi komunistNedeljni Dnevnik , Revija 92 , and Stop . There are over 150 newspapers and magazines published in the minority languages of Albanian, Hungarian, Slovak, Romanian, Ruthann, Turkish, Bulgarian, and Romani (Gypsy). Fifty-two are printed in Albanian. The Republic of Serbia and the autonomous province of Vojvodina fund 16 minority publications.

Article 35 of the Constitution of Montenegro guarantees freedom of the press and public information. The media are free to provide uncensored information to the people without government consent. However, during the elections of 2000, the Montenegrin government forbade the state-run media from covering the elections.

In 1998 Serbia and Montenegro had 27 dailies with a circulation of 830,000. Six hundred and forty-three other newspapers published with a circulation of 3,880,000. The print media included 647 periodicals, and 4,777 book titles were published with 958 of them by foreign authors. In Serbia the print media does not have the same influence as the broadcast media. There are 13 major dailies printed in Serbia, 7 of which are privately owned, Blic , Nasa BoraDemocratijaDnevni Telegraf , Danas , 24 Casa , and Gradjanin . Three Serbian newspapers have strong ties to the government, Politika , Ekspres , and Novosti . Major Serbian weekly newspapers are Vreme , Nin , and Nedeljni Telegraf . There are 7 daily newspapers publishing in the province of Kosovo. With the end of the Milosevic era the nation's leading 15 newspapers are Borba , PolitikaVecernje Novosti Ekspres , PobjedaDnevnikNasa BorbaBlicDemokratija , GradjaninDnevni Telegraf24 CasaDanasVijesti , and NT Plus . Magyar Szo and Magyarsag are the autonomous province of Vojvodina's Hungarian dailies. Kosovo's leading newspapers are Jedinstvo (Serbian) and the Albanian language's Bujku and Koha Ditore . Major regional newspapers are Narodne Novine , Lid , and Puls .

In Montenegro the print media were allowed greater freedom to publish as part of the Montenegrin government's overtures to the European Union and the United States in a strategic plan to become independent of Serbia (Yugoslavia). In 2000 Montenegro had 135 print publications. Montenegro has 3 major dailies, Probjeda , considered a pro-government newspaper, Vijesti , a privately owned publication, and the Socialist People's Party newspaper Dan . Two major weeklies in Montenegro are the Monitor and Grafiti . Foreign publications and foreign broadcasting are freely available to Montenegrins.

Economic Framework

The Republics of Serbia and Montenegro are comprised of Serbs (62.6 percent), Albanians (16.5 percent), Montenegrins (5 percent), Hungarians (3.3 percent), and a variety of ethnic groups comprise the remaining 12.6 percent of the population. Serbs and Montenegrins are practicing Christians of the Eastern Orthodox rite (65 percent). Albanians are members of the Muslim faith (19 percent), and Hungarians are usually practicing Roman Catholics (4 percent). One percent of the population is Protestant, and the remainder of the population (11 percent) either does not follow a religion or worships in another faith.

The death of President Tito in 1980 is regarded as a watershed event in Yugoslav history because he was perceived as the firm hand that could keep Yugoslavia's diverse ethnic and religious groups together. Instead Tito failed to create institutions that could adapt to the changing needs of Yugoslavia and Yugoslavia's changing place in the European and world contexts. By 1983 Tito's successors and the Yugoslav people discovered the huge financial debt the nation had acquired in maintaining its unique brand of Communism. With the increasing likelihood of Communism's collapse, Yugoslavia was no longer an important nation that the West offered financial credits. In the decade after Tito's death, Yugoslav living standards declined, state industry was highly inefficient, and unemployment kept rising. The failure of the federal government of Yugoslavia to resolve economic crises led to ethnic, religious, and regional disagreements. A Yugoslavia governed by its Serb politicians was unable to adjust to a rapidly changing world and the imminent breakup of the republic into its constituent members.

Slovenia prospered from manufacturing and food processing. Croatia drew large numbers of tourists and tourists' dollars to its medieval cities and Adriatic beaches. Serbia feared the loss of economic clout should the Yugoslav state be restructured financially and politically. Should ethnicity define the republics of Yugoslavia, Serbs living in Croatia and Bosnia would be seriously affected if not directly discriminated against. Slobodan Milosevic began the symbol of Serbian nationalism and Serbian political and economic supremacy. In 1991Yu-goslav military attacks to keep Slovenia within the Yugoslav federation were repulsed within two weeks. Slovenia declared its independence and suffered the least of the former Yugoslav republics. Protecting Serbs and Serb interests in Croatia and Bosnia led to war first between Croatia and Serbia, and when Croatia successfully became independent, between Bosnia and Serbia. Almost half of the territory and population in Bosnia was Serbian. A Serbian republic was created and still exists, but in union with the Bosnian state of Croats and Muslims. The war between the Yugoslav republics led to considerable devastation in Bosnia and parts of Croatia. The war eventually came to Serbia when the Yugoslav Army began to suppress the Albanian population of Serbia's former autonomous province of Kosovo, and NATO forces retaliated. Much of Serbia's infrastructure was destroyed in the war over Kosovo. Montenegro remained outside the conflict and refused to support repeated Yugoslav (Serbian) requests for assistance.

The collapse of the Yugoslav federation in 1991 and a decade of war leading to the creation of the independent nations of Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, and civil war in Kosovo destroyed Yugoslavia's perceived economic prosperity of the previous three decades. The breakup of the Yugoslav republics resulted in significant losses for Serbia and Montenegro in mineral resources, technology support, industry, trade links, and markets. A decade of war further reduced the economic viability of Serbia. Before the devastation of war, Serbia and Montenegro manufactured aircraft, trucks and automobiles, tanks and weapons, electrical equipment, agricultural machinery, and steel. Serbia and Montenegro exported raw materials including coal, bauxite, nonferrous ore, iron ore, and limestone, and food and animals. Serbia sustained considerable destructive damage from NATO bombings of the capital Belgrade, the nation's factories, and transportation networks. Montenegro's increasing autonomy from Serbia was sanctioned by the European Union and NATO nations to weaken Serbia. Serbia continues to use the dinar as its currency, while Montenegro used first the German deutsche mark and now the Euro. Montenegro escaped the ravages of war and did not need its infrastructure rebuilt. With former President Milosevic on trial for war crimes, the West has offered a variety of economic packages to rebuild Serbia, provided suspected Serbian war criminals still-at-large are captured and turned over to NATO forces.

Press Laws & Censorship

The overthrow of the repressive Milosevic regime ended much of the press and media censorship that burdened the Yugoslav nation. Media closures, government takeovers, and the arrest of journalists and broadcast media personnel were drastically reduced. The 1998 Law on Public Information, restricting the type of information printed or broadcast, remains in effect and was approved while Yugoslavia was under attack by NATO forces. The law made it permissible for citizens and organizations to bring legal action against the media for printing or broadcasting material considered unpatriotic or against the territorial integrity, sovereignty, and independence of the country. All foreign broadcasts were banned in Yugoslavia. Under the Milosevic regime journalists were beaten, equipment destroyed, and foreign journalists detained. Under the Public Information Act, the Milosevic government frequently fined the independent media. The fines amounted to almost 2 million dollars. In 1999 the Yugoslav government issued new laws determining how the media could report the NATO attacks and the Albanian rebels fighting the Yugoslav army in Kosovo. Information about military movements and casualty reports could not be reported. All independent media were eventually shut down during the 1999 NATO bombings. After the war only 20 of the 33 independent radio and television stations went back on the air. The Yugoslav Minister of Telecommunications temporarily suspended the reallocation of broadcast frequencies and allocation of new ones until new regulations were approved. The many crises facing the republics of Serbia and Montenegro delayed a proper review of the existing media laws. It is assumed that the old laws are unlikely to be enforced.

The Ministry of Information for the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia has been dissolved. The Ministry of Justice and Local Government assumed responsibility for media registration. The Bureau of Communications is responsible for: informing the public of government policies and the work of individual ministries, communications support for events of consequence in Serbia, coordination of the public relations operations of individual ministries, organizing and conducting media campaigns for important governmental programs, and the preparation of reviews and analyses of domestic and foreign media reporting.

The print media in Serbia is regarded as less influential than the broadcast media and therefore has made a faster transition to more independent news reporting. Newspapers previously loyal to the Milosevic regime switched their loyalties and announced journalistic independence. Serbia's most reliable newspapers during the Milosevic era and after are the dailies Danas , Blic , and Glas Javnosti and the weekly newspapers Vreme and NIN . Beta News Agency remains the most respected private independent news agency.

With the end of the Milosevic era Yugoslavia has adopted very liberal regulations and simplified the procedure to allow the foreign press to enter the nation. Radio and television broadcasts from other nations are beamed to Yugoslavian receivers with short-wave broadcasts of foreign radio stations 24 hours a day. The Federal Republic of Yugoslavia has over 350 permanently accredited foreign correspondents from 40 countries working at 29 news agencies, 77 newspapers, and 59 radio and television stations.

On April 4, 2002, the Serbian government adopted a new draft law for broadcasting prepared by the Association of Serbian Journalists and the Independent Association of Lawmakers working with the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe and the Council of Europe to bring all Yugoslav media in line with European Union standards. The new law regulates the situation in the broadcasting field by creating a 15-member Broadcasting Agency to oversee all broadcast media for radio and television programming, issuing and revoking licenses, and levying fines. The state-run Radio Television of Serbia (RTS) becomes a public company to both serve and be financed by the people of Serbia. RTS will be operated outside any government controls and will not have a single Serb or foreign owner to avoid conflicts of interest. The Law of Telecommunications will allow RTS to keep at least two but no more than four national frequencies. The existing Law on Information is being reviewed for revision in the summer of 2002.

News Agencies

Tanjung is Serbia and Montenegro's federal government news agency, although there are plans to privatize it. There are four other news agencies serving Serbia, Beta , FonetBina , and Tiker . Montenegro's only news agency is the state-owned Montena Fax . There are an increasing number of major press associations serving Serbia and Montenegro, the International Press Centre (MPC), Journalists Federation (SNJ), Publishers and Booksellers Association, Independent Journalists' Association for Serbia and Montenegro, the Association of Private Owners of the Media, Media Center, and Right for Picture and Word.

Broadcast Media

In the Federal Republic of Serbia and Montenegro twenty-three television stations (19 in Serbia and 4 in Montenegro) are fully licensed. The other television stations and all the radio stations are in the process of applying for the right to broadcast. Jugoslovenksa RadioTelevizija is Yugoslavia's state information station. Major Serbian radio stations are Radio Belgrade, and Radio Novi Sad. Radio Podgorica is Montenegro's leading radio station, while Radio Pristina serves the province of Kosovo. State-run broadcast media include the Serbian Radio, the Serbian Television, and the Montenegrin Radio stations. Radio stations in Vojvodina broadcast in eight languages. In 1996, 2 independent radio stations were closed on orders of the Milosevic government.

Major television stations serving the Serb population are Belgrade TV, Radio-TV Srbije, and TV Novi Sad. Pristina TV broadcasts to Kosovo's Albanian population, while Podgorica TV serves the Montenegrin population. The largest opposition television station, Studio B, was closed by President Milosevic in 2000 but reopened after his overthrow. Prior to 2000, six private television stations broadcast, BK, TV Studio Spectrum Cacak, Kanal 9 Kragujevac, Pink, Palma, and Art Kanal. The Politika Publishing Company owns Politika, and the Municipal Government of Belgrade owns Studio B. The state-run Kosovar Radio and Kosovar Television broadcast a few hours a week in Albanian. TV Novi Sad broadcasts programs in five languages, Hungarian, Slovak, Romanian, and Ruthann.

The collapse of the Milosevic regime returned independent broadcast media to the airwaves with the pro-Milosevic broadcast media rapidly distancing itself from the government. Radio B92, broadcast via satellite and the Internet after repeated shutdowns during the 1990s, has resumed broadcasting within Serbia and is regarded as Serbia's most reliable independent news outlet. Radio Index and Radio Television Pancevo are increasingly regarded as reliable sources for news reporting. The majority of Serbia's radio stations were regarded as pro-Milosevic and currently attempt to be both neutral and supportive of the government. Unbiased broadcasting is compromised by the state's licensing of broadcast frequencies and the Serbian government's tendency to direct financial support toward traditionally pro-government stations. The federal government is reorganizing the state-run Radio Television Serbia (RTS), once regarded as a Milosevic propaganda tool. The European Institute for Media has recorded a sharp increase in the number of television viewers in Serbia to 75 percent of the population (2000). There are an estimated 120 television stations and 400 radio stations in Serbia with foreign broadcasts from the BBC and CNN now permissible. Foreign investment is influencing a number of former pro-Milosevic television stations including TV Pink.

Montenegro has 14 radio stations in addition to the state-run radio. Ten radio stations are privately owned and include Antena M, Gorica, Free Montenegro, Radio Elmag, and Mir, an Albanian language station. Besides the state-run television station, Montenegro had privately owned stations including NTO Montena, TV Blue Moon, TV Elmag, broadcast from Podgorica, and the Herceg Novi station TV Sky Sat. Because the Montenegrin government sought independence from Serbia, the republic's broadcast media were decidedly anti-Milosevic in tone but sought the support of the Montenegrin state government, which may compromise their objectivity. Independent Serbian broadcast media closed by Milosevic were able to broadcast over Montenegrin stations Montena,

The Serbian province of Kosovo lacked broadcast media until the arrival of NATO troops. Radio Television Kosovo (RTK) went on the air in 1999 as a public service station, which now broadcasts at least four hours a day. There are an estimated 35 unlicensed broadcast stations on the air in Kosovo. The United Nations has established a temporary set of regulations governing broadcasting in Kosovo, requiring media professionals to follow the rules of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the European Convention on Human Rights. There are some restrictions on information involving military personnel. There are 5 radio stations and 3 television stations now licensed to broadcast in Kosovo.

Electronic Media

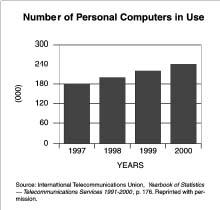

An increase in the number of computers will put more Serbians online. During the Milosevic era, filters were placed on computers at the universities to prevent students from accessing satellite transmissions. Ironically, the Internet contributed to keeping the media free and in bringing down the Milosevic regime. There are four Internet providers for the Serbian province of Kosovo: Pronet, Eunet, Co.yu, and PTT. Pronet is Albanian owned and operated. Anonymizer.com , part of the Kosovo Privacy Project, offers anonymous e-mail to both Serbs and Montenegrins. Internet Yugoslavia is under the Federal Public Institution Radio-Television Yugoslavia entrusted with the responsibility to create web presentations for the needs of the government and Parliament, monitor the Internet,

Education & Training

The University of Belgrade is Serbia's leading institution for the study of media and communications at the undergraduate and graduate levels. Founded in 1905 with 3 faculties (philosophy, law, and engineering) it grew to 7 colleges by 1941. The University of Belgrade currently consists of 30 colleges and 8 scientific institutes enrolling 65,000 undergraduate students and 2,500 students in graduate programs. Over 40 percent of the students are enrolled in the social sciences, with 28 percent in engineering, and 15 percent in medicine. There 5 branches of the University of Belgrade in Novi Sad (1960), Nis (1965), Pristina (1970), Podgorica in Montenegro (1974), and Kargujevac (1976).

Summary

The Albanian majority in Kosovo seeks independence from Serbia. The NATO and European Union nations are reluctant to sanction another republic from the former Yugoslavia. Serbia's political and religious historic sites from the Middle Ages are located in Kosovo. Serbian desire to hold on to Kosovo risks conflict with the Albanian majority in the province. The Serbian and Albanian ethnic rivalry inside Serbia affects its relationships with the neighboring states of the Former Republic of Macedonia and Albania. In 2002 Crown Prince Alexander, his wife, and three sons were given Yugoslav passports and invited to return to live in Yugoslavia along with the extended Karadjordje family. Crown Prince Alexander was returned the keys to the royal palace located in downtown Belgrade and the White Palace in the suburbs. While there is renewed interest in the monarchy, it is not clear if the concept of monarchy will be used or can unite a fractious population of what is left of the former Yugoslavia. Since the downfall of Milosevic, Serbia has made dramatic changes in the laws and government policies affecting the media. The Federal Republic of Serbia and Montenegro has every intention of conforming to European Union standards for the communications industry. Redevelopment of an economy devastated by a decade of war will take time to rebuild, even with substantial foreign aid grants. Serbian banks have a combined debt of over $1.6 billion created by suspected Milosevic manipulations within the banking system.

Industrial production remains low, unemployment high, and there are large numbers of refugees to resettle and financially support. Success will depend on the skills of the politicians, the stability of a multiparty democracy, and how long the people of Serbia are willing to wait for the reforms to be made and become effective. The people of the former Yugoslavia once enjoyed one of the highest standards of living in Eastern Europe. They are not used to being perceived as international pariahs, but it is clear that the people of Serbia and Montenegro are working hard to get beyond the Milosevic era and becoming integrated into the Europe of the European Union.

Significant Dates

- 1999: Kosovo crisis and NATO military intervention.

- 2000: Milosevic defeated in a free election.

- 2001: Milosevic taken to The Hague for trial as a war criminal.

- 2002: Federal Republic of Yugoslavia is replaced by the Federal Republics of Serbia and Montenegro.

Bibliography

Allcock, John B. Explaining Yugoslavia . New York: Columbia University Press, 2000.

Dragnich, Alex N. Serbia, Nikola Pasic, and Yugoslavia . New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1974.

Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Available from http://ww.gov.yu .

Glenny, Misha. The Balkans, Nationalism, War and the Great Powers, 1804-1999 . New York: Viking, 1999.

Graham, Stephen. Alexander of Yugoslavia . Hamden, CT: Archon Press, 1972.

International Journalists' Network. Available from http://www.ijnet.org .

Judah, Tim. The Serbs, History, Myth and the Destruction of Yugoslavia . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997.

Kaplan, Robert D. Balkan Ghosts . New York: St. Martin's Press, 1993.

Martin, David. The Web of Disinformation, Churchill's Yugoslav Blunder . San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1990.

The Media in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia . Novi Beograd, Yugoslavia: Federal Secretariat of Information, 1997.

Own, David. Balkan Odyssey . New York: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1995.

Turner, Barry, ed. Statesman's Yearbook 2002 . New York: Palgrave Press, 2001.

United States Institute of Peace. Special Report: Serbia Still at the Crossroads . March 15, 2002.

World Mass Media Handbook, 1995 Edition . New York: United Nations Department of Public Information, 1995.

William A. Paquette

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: