Uzbekistan

Basic Data

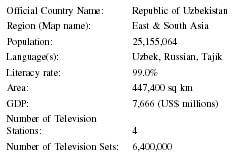

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Uzbekistan |

| Region (Map name): | East & South Asia |

| Population: | 25,155,064 |

| Language(s): | Uzbek, Russian, Tajik |

| Literacy rate: | 99.0% |

| Area: | 447,400 sq km |

| GDP: | 7,666 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Television Stations: | 4 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 6,400,000 |

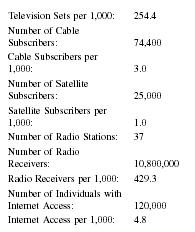

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 254.4 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 74,400 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 3.0 |

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 25,000 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 1.0 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 37 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 10,800,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 429.3 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 120,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 4.8 |

Background & General Characteristics

The state of the press in Uzbekistan has to be viewed in the context of a century old repressive Russian rule, first as a part of the authoritarian Czarist regime and then as a constituent of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). On September 1, 1991, Uzbekistan cut itself loose from the Soviet Union and proclaimed itself a sovereign republic. It has the distinction of being the most authoritarian country in Central Asia, with no real domestic opposition; its media is generally tightly controlled media despite the constitutional provisions for a free press without censorship. The head of Uzbekistan's authoritarian government, President Abduganiyevich Karimov, is a long-time, high-profile member of the Uzbek Communist Party's Central Committee and a cabinet minister in the Soviet Uzbek government (most notably as finance minister), He is accustomed to political obedience from one and all including the press. In 1990, Karimov became president of the Soviet Uzbek republic, and in December 1991, following the fall and break-up of the Soviet Union, he became the country's elected president. When the country first gained its independence. there was a somewhat benign attitude toward the media in keeping with the Birlik movement, the Uzbek equivalent of perestroika. Analysts have noticed that his authoritarianism has worsened since the mid-1990s, perhaps because of his determination to root out the Islamic fundamentalism that has raised its head since the Soviet defeat in neighboring Afghanistan; he wants his government to remain secular.

Although President Karimov periodically mouths platitudes espousing the cause of freedom of the press and asking his ministers and officials to work closely with the media, his numerous legislative measures, administrative fiats, and pressure placed on the judiciary to mete out severe punishments to independent-minded journalists leave no doubt about his policy to streamline the press and make it support his political agenda,, including economic policies. His policies resemble those of China in combining economic liberalization with political repression. Part of the latter includes tightening controls over the press and ending "intolerance of defiance" among journalists and broadcasters.

Historical Traditions

Uzbekistan, Central Asia's most populous country, located between Amu Darya and Syr Darya Rivers, has had a long and glorious heritage. Its famous cities—Samarkand, Bukhara, and Khiva—lay on the vital Silk Road, the trading artery of premodern times linking China with the Middle East and the Mediterranean. On his way to India, Alexander the Great stopped near Samarkand long enough to marry Roxana, daughter of a local chieftain. Uzbekistan came under Arab rule in the eighth century A.D. The local Samanid dynasty established an empire in the ninth century. In 1220, the Mongol leader, Genghis Khan conquered the territory. In the fourteenth century, Timur Lane built an empire with Samarkand as his capital, which he adorned with many monuments. The empire then broke into several principalities, some of which joined Persia. In 1865, when Czarist Russia conquered Tashkent, the present capital of Uzbekistan, the major political entities in the present-day Uzbekistan were the Khanates of Kokand, Bukhara, and Khiva. Russia incorporated Kokand in 1876 and allowed the other two to remain as protectorates.

Following the formation of the Soviet Union, the Soviet Socialist Republic of Uzbekistan was established in 1924 from the territories of the protectorate Khanates of Bukhara and Khiva, and Ferghana, which constituted a portion of the former Khanate of Kokand. During the Soviet Union's control, Uzbekistan was developed into one of the largest cotton growing centers thanks to an irrigation system based on the Aral Sea. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, its Central Asian Republics proclaimed their independence; Uzbekistan did so on September 1, 1991, under the leadership of Islam Karimov, the powerful former First Secretary of the Uzbekistan Communist Party. He was elected president of the country in December of the same year.

Constitution

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, Uzbekistan became independent on September 1, 1991. Under a constitution effective December 8, 1992, it became a republic with a separation of powers. Although the executive consists of the president, prime minister, and the cabinet, in reality, President Islam Karimov holds firm control over the government as President and Chairman of the Cabinet of Ministers. He also appoints and dismisses provincial governors, who answer only to him. Under the terms of a referendum held in December 1995, Karimov's first term was extended by five years; another referendum held on January 27, 2002 extended it to December 2007. The constitution provided for a unicameral legislature, the Olly Majlis, or Supreme Assembly, of 250 members. It meets only a few days each year and has very little power to shape legislation. The referendum of January 2002, proposed a bicameral parliament. The judiciary, consisting of the Supreme Court, constitutional court, and economic court, lacks independence.. The country is divided into 12 villoyatlars, or administrative subdivisions, plus the autonomous region of Karakalpakstan and the city of Tashkent. All those 18 and above have the right to vote "unless imprisoned or certified as insane." Uzbekistan is theoretically a multiparty democracy. However, government approval is needed for the formation of a party. The prominent parties in the current Supreme Assembly are: Adolat (Justice) Social Democratic Party, which was established in 1995; Democratic National Rebirth Party (Milly Tiklanish Democratic Party, or MTP, established in 1995; Fatherland Progress Party (Vatan Tarakiyoti, or VTP), which merged in April 2000 with the National Democratic Party (Fidokorlar, or Fidokorlar Milly Democratic Partiya); and the People's Democratic Party, or PDPU (Uzbekistan Halq Democratic Partiya, formerly Communist Party, which was established on November 1, 1991).

Newspapers

In 1999, there were 471 newspapers and magazines, of which 328 were published by the various ministries and departments of the government, state enterprises, or "political parties." Almost all newspapers are printed at the state printing facilities, which makes it convenient and not-so-obvious for the print copy to be censored. Of the total number, 66 may be regarded as national, 68 regional (although the government does not accept such a category on grounds that Uzbekistan is not split into regions), and the remaining local. Some 109 were public or organizational, representing trade unions, the military, or other associations. The remaining 34 were in the private sector, which is a growing segment and financially independent of the government. They were mostly commercial or religion-based.

Listed below are the principal newspapers of Uzbekistan, the year of their founding, name of the owner, and circulation (wherever available):

Uzbek Newspapers:

- Uzbekistan Ovozi, June 21, 1918; People's Democratic Party; 40,000

- Uzbekistan Adabieti Va Sanati ( Literature and Art of Uzbekistan ); January 4, 1956; Ministry of Culture & Association of Writers; 6,500

- Marifat ( Education ), 1931, Ministry of Education, 21,500

- Adolat ( Justice ); February 22, 1995; "Adolat" Socialist Democratic Party; 5,900

- Turkiston, 1925, "Kamolot" Youth Foundation, 8,000

- Toshkent Hakikati ( Tashkent Truth ), February 1954, Tashkent Oblast Administration, 19,000

- Mulkdor ( Proprietor ); January 10, 1995; Real Estate Exchange & State Committee for Entrepreneurship; 20,000

- Hurriyat, December 1996, Fund for Democratization of Media, 5,000

- Savdagor; August 19, 1992; Uzbeksavdo & Uzbekbirlashuv firms, 17,000

- Fidokor, May 1999, NDP, 32,000

- Sport; June 2, 1932; State Committee for Sport & Physical Training; 8,500

- Respublika; September 1, 1998; UzA Government Wire Service; NA

Uzbek/Russian Newspapers:

- Narodnoe; January 1, 1991; Government; 50,000

- Biznes Vestnik Vostoka (BVV), August 1991, Pravda Vostoka and Uzfininvest Joint Stock Company, 20,000

- Novosti Nedeli, August 1996, National Commodity Exchange, 5,000

- Na postu/Postda; May 12, 1993; Ministry of the Interior; 18,000

- Soliqlar va Bojhona I Tamojennie Vesti, January 1994, State Tax Committee, 45,000

- Vechernly Tashkent/Tashkent Oqshomi; January 1, 1966; City Mayor's Office, NA

English Newspapers:

- Good Morning

- Uzbekistan Ovozi Times

- Business Partner

- Business Review

Russian Newspapers:

- Pravda Vostoka ( Truth of the East ); April 2, 1917; 20,000

- Tashkentsaya Pravda, February 1954, Tashkent Oblast Administration, 6,400

- Business Partner Uzbekistana

- Golos Uzbekistana ( Voice of Uzbekistan ); June 21, 1918; PDP; 40,000

- Uchitel Uzbekistana ( Teacher of Uzbekistan ); January 1, 1980; Ministry of Education; 7,000

- Norodnoe Slovo ( People's Word )

- Molodyozh Uzbekistana ( Youth of Uzbekistan ), November 1926,"Kamolot" Youth Foundation & "Career-Service" Agency, 6,000

- Vechernij Tashkent ( Evening Tashkent )

- Business-vestnik Vostoka, Bvv ( Business News of the East )

- Novly Vek (formerly Kommercheskij Vestnik, Commercial News), January 1992, State Property Committee, 22,000

- Chastnaya Sobstvennost, May 1994, State Property Committee, 8,000

Russian/English Newspapers:

• Delovoy Partner, 1991, Ministry of Foreign Economic Relations, 20,000

Economic Framework

Uzbekistan has a large agricultural sector and is a leading exporter of cotton. The economy is primarily based on agriculture and processing of agricultural products. The country is a part of the large Central Asian oil and gas fields. Its potential, particularly for the export of natural gas, is immense. Uzbekistan is also a major producer of gold, with the largest open-pit gold mine in the world, and has substantial deposits of copper and strategic minerals.

Uzbekistan's economic performance, however, is mediocre, largely because of the restrictive trade and investment climate that is a hangover of the communist system. Of late, the government has publicly committed itself to a gradual transition to a free market economy. China seems to be the government's role model, combining economic liberalization and political repression. Yet, it falls far short of the intended liberalization, which is the reason why there is very little foreign direct investment in the country. In 2002, Uzebekistan signed the Staff Monitored Program (SMP) with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to introduce current account convertibility. Thus far, a very restrictive exchange regime is justified on grounds of the need to limit the imports of consumer goods and to channel the foreign exchange to finance the import of machinery and high technology. If the IMF reforms are implemented, the country would attract much-needed foreign direct investment. Analysts point out that what is really needed to move the economy forward is major structural reform, which should include getting rid of the state controls over the vital agricultural sector.

In March 2002, Uzbekistan devalued the exchange booth rate from approximately 920 to about 1,300, much closer to the curb market rate. The aim is to reduce the gap between the official and market rates, with the curb rate not to exceed 20 percent by June 2002. In April, 2002, a new decree allowed the sale of bonds by the Central Bank of Uzbekistan, which utilizes technical advice from the World Bank, the UNDP, and the U.S. Treasury Department's Office of Technical Assistance. All these measures are expected to pump some momentum in the country's fiscal and monetary policy to make them truly market-oriented.

Uzbekistan's exports, according to 2000 government statistics, were $3.26 billion, mainly cotton, gold, natural gas, mineral fertilizers, ferrous metals, textiles, and food products. Major export markets are Russia, 16.7 percent; U.K., 7.2 percent; Switzerland, 8.3 percent; South Korea, 3.3 percent; and Kazakhstan, 3.1 percent. The imports were $2.94 billion, mainly machinery and equipment, chemicals and foodstuffs. Major partners were: Russia, 15.8 percent; South Korea, 9.8 percent; United States, 8.7 percent; Germany, 8.7 percent; Kazakhstan, 7.3 percent; and Ukraine, 6.1 percent. Uzbekistan's external debt in 2001 were estimated at U.S.$ 4.5 billion.

Financial Condition of Newspapers

In terms of finance, the government subsidizes only a very limited number of newspapers. Most of them sustain themselves on the revenues they receive from advertisements, many of which are in the form of announcements, notices, or calls for tenders from various state agencies. Another source of income indirectly provided by the government is mandatory subscriptions by the various state offices to the state publications, The newspapers do not get much advertising from international companies, which find it difficult to operate because of the laws disallowing currency convertibility.

Press Laws

The Constitution of Uzbekistan plainly provides "freedom of thought, speech and convictions." Article 67 of the Constitution states that "media are free … censorship is impermissible." Yet in reality, the press and the other media experience censorship. Moreover, there are registration requirements that are misused to screen those who want to start a newspaper or magazine or renew their licenses. The basic law governing the media was adopted on June 14, 1991, three months before Uzbekistan's independence from the Soviet Union. It was supplemented by several decrees and regulations, including decree number 244, which laid down rules for registration. On November 26, 1996, the Uzbek Parliament promised liberalization of the press, to bring it in line with international standards. The following February, it adopted several laws on the relationship between the government and the media. Article 4 of the Law on Mass Media reiterated: "In the Republic of Uzbekistan, censorship on mass media is not permitted. No one has the right to request that materials and reports be approved prior to publication, or that any text be altered or completely removed from print (air)."

Censorship

Although the constitution of Uzbekistan and the Law on Mass Media forbids censorship, the government has "enforced a virtual censorship." The Committee for the Protection of State Secrets at the State Print Committee acts as an unofficial censor, having the authority to approve the newspaper copy before it goes for printing. Significantly, the Law on Mass Media does not provide for solving the disputes in court; it gives that authority to the State Print Committee, actually placing the latter above appeal or arbitration proceedings. In fact, this committee censors newspapers before publication and radio and TV texts and footage before they are broadcast. Television and radio stations practice self-censorship so well that the Committee, by and large, does not find it necessary to censor the broadcasts on a daily basis.

The process of self-censorship is further helped by the fact that most editors and media executives fall under the jurisdiction of the Office of the President, or some minister or the other. Therefore, editors and the top echelons of the media hierarchy put certain types of programs "off limits" by way of self-censorship. The self-censorship is also encouraged by a number of administrative measures. The government's ire is manifested through endless delays in registration and license renewals, judicial decrees, or obstacles in purchasing news-print. Consequently, as a professional organization commented, the "media landscape is one-sided. There are no opposition media in the country; the independent media in the private sector simply refrain from political reporting. The media appear to compete for the title 'most loyal to the authorities."'

In mid-1996, President Karimov announced he would liberalize the press. Six months later, even while the new law was on the legislature's anvil, the newspaper Vatan was temporarily closed down for publishing an analytical article on the President's human rights policy agenda. In February 1997, the parliament passed laws on the access to information and the rights of journalists. Although these appear liberal on paper, they have not been implemented, nor has their been qualitative change in the working conditions of journalists or in the subtle standards of censorship imposed through "self-censorship." The 1991 law prohibiting writing that would "offend the honor and dignity of the president" continues. The new laws hold journalists responsible for the accuracy of their reporting and potentially subjects them to criminal prosecution if the government officials who are under scrutiny disagree with news reports. The new laws also permit closure of any media outlet without court judgments, prohibits incitement of ethnic or religious conflict, and disallow the registration of organizations whose purposes include "subverting the constitutional order." And although there is no official censorship, no newspaper can be printed (all printing facilities are state-owned) without the prior approval of the Committee for the Control of State Secrets.

Even the newspapers and magazines in the private sector are not free from editorial constraints. In fact, "true" opposition papers ceased to exist in 1993, when severe restrictions were imposed on the media. Although the restrictions were relaxed in 1997, the harsh sentence of 11 years meted out to a Samarkand state radio reporter, Shodi Mardiev, in 1998, and the manhandling of two Russian journalists for talking with human rights activists in the same year, were enough proof that the government expected self-censorship of all journalists.

State-Press Relations

In practice, the government created a process that effectively compels obedience and loyalty on the part of the press through self-censorship. This was done through the Uzbekistan State Committee on the Press, which was supposed to protect the rights of the press and the journalists. Instead, its chairman, who is close to the president's office, has been placed in charge of the registration and renewal of licenses to media companies, as well as the accreditation of journalists. The authority is often used to streamline those deemed "prejudicial to the public good". The State Committee on the Press also regulates the availability of newsprint, which is a monopoly held by a state-owned agency. In order to enforce the provisions of the "law," the committee maintains an Inspectorate.

The other laws affecting the media adopted in 1997 includes one guaranteeing freedom of access to information. It lists the various categories of information "except for the state secrets" to which the citizen would have access. Most of the access guaranteed under article 3 of the law was taken away by the limits set in article 9, which forbid "state agencies, bodies of citizen self-government, public associations, enterprises, institutions, organizations and officials" to provide information containing "national secrets or other secrets protected by law." Another piece of legislation entitled "On the Protection of the Professional Work of Journalists" defined a journalist and listed his/her basic rights, notably in investigative journalism. It also laid down guidelines for the accreditation of foreign journalists working in Uzbekistan and for Uzbeki journalists working abroad. As for the broadcasting media, they come under the Ministry of Communications for the issue and renewal of licenses. The Uzteleradio, the Television and Radio Company of Uzbekistan, which operates in the capital as well as in the provinces, is directly responsible to the government through the Ministry of Broadcasting for their programming.

In sum, although the extensive 1997 legislation concerning the media was in keeping with President Karimov's promise in mid-1996 that he would improve journalists' working conditions, in practice, the several laws passed by the Parliament in 1997 have "not translated into a free and pluralistic media landscape." Besides, the new laws did not invalidate the 1991 law that prohibited any criticism "offending the honor and dignity of the president." Reviewing the media laws and the bureaucratic structure controlling the media, Roger D. Kangas lamented: "For organizations that have followed Uzbekistan's policy of complete media control, such laws might very well be considered empty additions to the litany of legislation that has little substantive meaning. the reality has been a system wherein the media remains completely censored by the government and void of serious debate on current political issues."

Can such restrictions, including self-censorship, be viewed differently from the working conditions of journalists in countries where the freedom of the press is truly guaranteed by the courts? Thus, the practice of self-censorship may rightly be equated with official censorship and condemned in truly democratic countries. However, in societies accustomed to tight government control of many aspects of life, self-censorship may not appear tyrannical. A survey conducted in the year 2000 indicated that 38 percent of journalists in Uzbekistan felt some kind of censorship was necessary to protect against anarchy. A prominent Uzbek TV journalist and station director, Shukhrat Babadjanov, attributed such thinking to "the absence of democratic thinking in the mentality of the Uzbek journalist."

One major exception to such self-censorship is the independent Uzbek-language Hurriyat ( The Liberty ), which publishes articles and stories critical of government officials in numerous state enterprises but not of the top hierarchy.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

The presence of foreign media in Tashkent is impressive for its comprehensiveness but not for its staffing, which, with the exception of Russian Public Television (ORT), is mostly at the level of local stringers. The foreign media represented are: Reuters, Agence France-Presse, Russian news agencies (Interfax; ITAR-TASS; Novosti, ORT news bureau), Internews (U.S.), Associated Press, UPI, BBC, VOA, Radio Liberty, and Chinese Economic Daily. The government is polite and helpful to foreign media and though it expects them to follow the same guidelines as the domestic media, in practice, the foreign media, particularly those from Western Europe and the United States, prefer to have a low-profile presence rather than confrontation with the government.

Russian Media In the CIS and In Uzbekistan

Rus-sian is widely spoken throughout the CIS, including in Uzbekistan. The Moscow-based media, notably the Russian Public Television (ORT), is available everywhere and is almost invariably more popular than the domestic state-controlled TV channel. Russian channel 1, RTR, as well as the private channels TV-6 and NTV, are fairly popular thanks to the greater freedom their news broadcast and current affairs programs, mostly political, show. Another reason for their popularity is that both the ORT and RTR include American soaps in their programming, which makes the channels popular with large audiences. Some CIS members, however, like Uzbekistan, have taken steps to delay and censor the Russian transmission because they fear the impact of the discussions on current affairs unpalatable to the governing regime in Uzbeki-stan.

Russian newspapers and magazines do not have an equally attractive market in Uzbekistan, or for that matter, in the CIS. One major reason is the problem with currency convertibility, which makes the cover price of Russian newspapers prohibitive in Uzbekistan. Even so, prominent newspapers such as Pravda, Izvestya, Argumenti I Facti and Trud are available on newsstands in Tashkent and are regularly read by the political elite and Uzbeki media persons.

News Agencies

There are three main news agencies. UzA is the national information agency, owned by the state and serving as a channel of information which is carefully screened before its distribution to newspapers. Jahon News Agency is run by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, reporting mostly on the Uzbek presence and activities of its diplomatic establishments abroad. It also assists the flow of information from Uzbekistan to the outside world and, in the process, controls the content. It also serves as a liaison with representatives of the foreign media in the country. Lastly, Turkiston Press Outside World Agency is a new, independent agency established by young, professional journalists. It has so far managed to steer clear of government intervention.

Broadcast Media

Radio

Just as in television, there are state-owned and independent radio stations in Uzbekistan. The State Radio has FM, medium-wave and short-wave transmissions. The State Radio has four channels, each with its own specialty: Channel 1 ("Uzbekistan") is the most important channel, paralleling Uzbek TV 1 in its programming (frequencies; LW, MW, SW, FM); Radio Channel 2, popularly known as "Mashal" (MW and FM), is directed to the youth and has more entertainment programs than others. Radio Channel 3, known as "Dostlik" (MW and FM) focuses on the minorities in the country; Radio Channel 4, known as "Yoshlar" (MW and FM), is directed toward the youth. Yet another government-owned radio station, "Radio Tashkent" broadcasts on a short-wave to numerous countries in 12 languages.

There are seven FM radio stations in the capital city of Tashkent, one independent station that covers the three provinces of Ferghana, Andijan, and Namanghan. Five out of those in Tashkent are independent, Radio Grande (FM-101.5 MHZ) being the most popular among them. It was established in 1999 with substantial assistance from the Konrad Adenauer Foundation in Germany and the International Center for the Training of Journalists. It has one-hour programs in Russian, Uzbek, and English every day and besides music, it broadcasts hourly news— local, national, and international. Among the other private FM stations is radio Sezum, an Uzbek-US joint venture.

Television

According to the U.S. nongovernmental organization, Internews, there are about 35 independent TV stations in Uzbekistan along with the State TV and Radio Company. It is not designated as a "state" company by a decree of the Uzbek Cabinet, which expects it to be financially fully independent "as soon as possible." Analysts observe that, given its size and operations and the state of the private sector, it is likely to be state-owned for a long time.

The State TV, which was predominantly dependent on Russian programs in the first few years, has reduced the transmission of broadcast hours of Russian channels like ORT and RTR. In order not to deprive people who would like to continue to watch Russian television as well as to cater to the sizeable ethnic Russian population in the cities, the government has encouraged the growth of cable TV, which operate as small stations providing individuals with such a service for a monthly fee. Such cable TV stations often provide international programs with channels such as CNN, TNT, ESPN, and BBC. The largest of the cable TV stations is Kamalak TV, with as many as 10 Russian and international channels.

The Uzbek government manages not to allow any "independent" TV stations to operate in the capital city of Tashkent, where political sensitivities matter far more than in smaller cities and towns and the rural areas. The one exception is Channel 30 in Tashkent, which walks a tightrope in terms of self-censorship. It also transmits foreign and Russian licensed programs. The independent stations mostly broadcast to provincial areas. Even so, they practice self-censorship, only less than the State TV. Most independent stations have outmoded equipment and depend on the U.S. Internews, which helps them by providing equipment and training. Because most independent stations do not and cannot afford sophisticated editorial staff, the Internews collects news reports from most of these stations, develops them into a program, and then redistributes the news program to the stations ready for broadcast.

Although all independent stations are, by definition, financially independent, some of them, such as those in Samarkand and Andijan are well-funded and can afford plans for expansion and quality improvement. They have their own news programs at the local level and are not, to that extent, completely dependent on the Internews. Besides, they have their own talk shows, which they broadcast on their own FM radio stations as well.

The State TV has four channels, each with a different coverage, language of broadcast, and content. The Uzbek Channel 1 is the primary channel, and bears a resemblance to C-SPAN, with an emphasis on all government activities, speeches, and public events, with a pronounced political and economic bias. It broadcasts in Uzbek (except for news in Russian) and is the most censored of all State TV channels. The Uzbek Channel 2 is called "Yoshlar," or Youth Channel. It covers one-half of the geographical area of the country. Although the channel is supposed to compete with Channel 1, its coverage, apart from some emphasis on "entertainment of the youth" covers political events such as presidential and parliamentary elections, political events, and talk shows on political and economic issues. The channel uses both Uzbek and Russian in its broadcasts, It is, like Channel 1, subject to strict censorship. Channels 3 and 4 are entertainment-oriented with movies, and sports;Channel 3, also known as TTV because of its coverage focused on Tashkent, sometimes creates its own programs.

All four channels retransmit pirated western and Russian movies and other programs by downloading them off satellites and dubbing them into Uzbek and/or Russian. Copyright violations are routine in Uzbekistan despite the country's membership in the International Intellectual Property Organization.

Electronic News Media

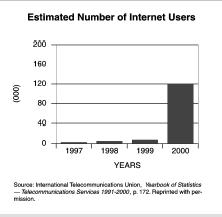

There are several companies that provide paging, cellular phones, and cable TV—all of them based in Tashkent: Kamalak-TV; Radio Page; Kamalak-paging; Orbitel Ltd. Scooner Trading Telecom, U-tel, and Uzdunrobita. In the decade following its independence from the former Soviet Union, Uzbekistan's telephone services have improved remarkably. So has the demand for telephones despite the increase in the tariff since the mid-1990s. The demand from rural areas has outpaced that from urban centers, with the overall increase in telephone connections totalling 250 per cent since 1991. While it is almost impossible to gauge the numbers of users of the Internet anywhere, the impact of the Internet is far greater than such numbers may indicate. According to Yash Lange, who regularly monitors the media in the CIS, the access to the Internet is so far "confined to the educated, successful or (often) young" limited by the "obsolete telecommunication infrastructure" that inhibits expansion. Thus, a survey conducted in January 1997 placed the number of hosts in Uzbekistan at 122, which compares most unfavorably with Russia: 50,000; Ukraine: 6,966; Kazakhistan: 807; Georgia: 210; and Armenia: 175.

There are several reasons for such a limited use of the Internet. Only a small minority can afford an IP connection that would enable them to surf the Web or have access to e-mail. It is also not possible to determine the exact number of users since the number of subscribers at the providers gives the number of connections, not the number of users, who pay a small fee to the subscribers for the facility. This is especially true of universities and research institutes where a single connection may be used by several faculty, researchers, and students. While the cost of a connection is prohibitive, even the hourly use charge can be very high, particularly to young people who do not have access to a common academic facility.

The impediments to Internet expansion include poor telecommunications infrastructure, the over-loaded, low-speed international channels which make the use of the Web complicated. This is so in Russia itself; it is many times worse in the CIS including, Uzbekistan. Another problem is the alphabet used by the receiver and the sender in transmitting the data if it is not in Roman script, which is used on the Internet. Moreover, the Internet is predominantly in English. "As data travels from one system," Lange notes, "the messages may change (parts of words disappear) because the server where the message travels through on its way to its final destination may not support the type of coding. … When messages are sent from east to West it becomes much more pronounced." Yet, the greatest hurdle in the expansion and use of the Internet would be the will of the government and its desire to link its citizenry with the world, in seeing the inevitability and long-term benefits of such an interaction. Uzbekistan is, in this respect, way behind Russia and Ukraine; its newspapers are not yet on line.

Education & Training

Training in journalism and telecommunications is given at the Electro-technical and Communication Institute, 108 Amir Temur Street, Tashkent (Tel. 35-0934).

Summary

The contradiction in President Karimov's pronouncements on the freedom of the press and the reality of repression was most clearly manifested in the case of Shodi Mardiev, a Uzbek state-run radio reporter sentenced by a Samarkand court on June 11, 1998 to 11 years in prison. He was found guilty of slandering an official in a program satirizing the alleged corruption of the Samarkand deputy prosecutor and of attempting to extort money from him. According to the New York-based Committee for the Protection of Journalists (CPJ), the prosecution and the sentence were "in reprisal" for Mardiev's generally critical stance toward government officials. In addition to writing to the Uzbekistan president, the CPJ drew attention to the plight of Mardiev and two other imprisoned journalists at hearings on human rights in Washington D.C. in April 2000 and July 2001. It was a matter of great relief and joy to the media community that Shodi Mardiev was released in January 2002, in terms of a presidential amnesty order of August 22, 2001, marking the 10th anniversary of Uzbekistan's independence from the former Soviet Union. The amnesty was extended to some 18,000 ordinary prisoners including about 700 religious and political detainees. Mardiev was eligible for early release on grounds that he was over 60 (he was 63 at the time of his release). A special circumstance that is advanced by the government as an excuse for "supervising" the media, is the need to contain the insurgency conducted by the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan. Ironically, on June 27, 2001, declared "Press and Media Workers Day" in Uzbekistan, President Karimov warned the journalists that they would suffer serious consequences if they complained about restrictions even where the national security was involved. It is not just the issues related to Islam that provoke the government's ire. Even expressions of discontent over the government's economic performance are closely "monitored" by the government, and frequently editors of newspapers and magazines receive calls—they never write—from the State Press Committee or from the President's office ordering

Significant Dates

- 1990: Karimov becomes President of the Soviet Uzbek Republic.

- 1991, June 14: The Basic Law for the Media approved.

- 1991, September 1: Uzbekistan becomes an independent Republic.

- 1991, December: Karimov becomes President of the Republic of Uzbekistan.

- 1992, December 8: Uzbekistan adopts a constitution.

- 1995, December: Referendum held; Karimov's term as president extended by five years.

- 1996, November 26: Parliament promises liberalization of the press.

- 1997, February: Parliament approves law on access to information.

- 1999: Radio Grande inaugurates its services

- 2002, January 27: Referendum held; extends Karimov's term as president till December 2007.

Bibliography

Bey, Yana. "When a Free Press Might Aid Terrorists, Getting News in Uzbekistan," World Press Review Online (November 14, 2001).

Internews, Uzbekistan, "Radio Stations of Uzbekistan," available online at www.internews.uz/uzradio.html

Internews, Uzbekistan, "TV Stations of Uzbekistan," available online at www.internews.uz/uztvs.html )

Kangas, R. D. "New Media Law in Uzbekistan: Finally Turning the Corner?" OMRI Analytical Brief no. 556 (February 24, 1997).

Kabirov, Lutfulla. "Structural Reconstruction of Uzbek Press," Post-Soviet Media Law and Policy Newsletter nos. 4-49 (September 15, 1998). Kabirov is director of the Creative Center for Journalists, Likhom, in Tashkent.

Johnson, Eric, with Martha Olcott and Robert Horwitz. "The Media in Central Asia. An Analysis Conducted by Internews for USAID." April 1994.

Lange, Yasha. "Media In the CIS:Uzbekistan," (May 13, 1997) Available online at www.internews.ru.books.

Open Society Institute (New York), Central Eurasia Project. "Journalists Struggle to Cope with Censorship in Uzbekistan." (July 3, 2001). Available at http://www.Eurasianet.org.

Republic of Uzbekistan. "Law on the Mass Media." (December 26, 1997) Available on www.internews.uz/law4e.html.

U.S. Department of State. Uzbekistan Country Report on Human Rights Practices for 1997. (January 1998) Available online at www.state.gov/.

Damodar R. SarDesai