Venezuela

Basic Data

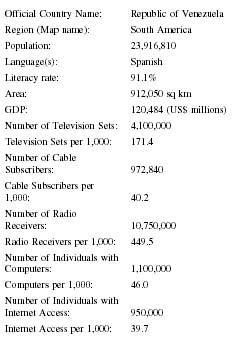

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Venezuela |

| Region (Map name): | South America |

| Population: | 23,916,810 |

| Language(s): | Spanish |

| Literacy rate: | 91.1% |

| Area: | 912,050 sq km |

| GDP: | 120,484 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Television Sets: | 4,100,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 171.4 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 972,840 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 40.2 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 10,750,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 449.5 |

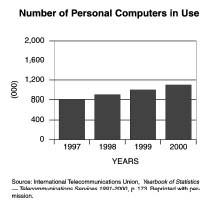

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 1,100,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 46.0 |

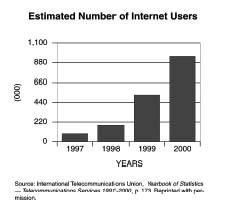

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 950,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 39.7 |

Background & General Characteristics

General Description

Venezuela is bordered by Colombia, Brazil, and Guyana, and has coastline touching the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. Its population was estimated at 22.8 million in July of 1998. The nation covers an area of 912,050 square kilometers, with the population heavily concentrated in the northern regions near the coast. The official language is Spanish, but a small portion of the population speaks indigenous languages. The ethnic mix of the population is 21 percent Caucasian, 10 percent African, and 2 percent Native American with the remaining 67 percent reported as a mix of two or more of these groups. The Roman Catholic Church claims 96 percent of the population, although church attendance and religious enthusiasm are minimal. Two percent of the population identifies with various Protestant groups, and the remaining two percent with some other religion or no religion. The literacy rate is reported at 91.1 percent.

As in much of Latin America, geographic factors play a strong part in dictating demographic patterns. A vast percentage of Venezuela's population lives within 50 miles of the Caribbean coast, between the sea and the Cord de Mérida mountain range that runs from the southern end of Lake Maracaibo to the capital. The area south of the mountains, comprising the large Orinoco River basin, supports a relatively small population with most of these living north of the river. South of the river is largely rain forest, very sparsely populated by mostly indigenous people although it represents slightly more than half of the land mass of the nation.

Venezuela's economic well being depends largely on the continued success of the petroleum industry. This sector accounts for a third of the nation's gross national product each year and roughly 80 percent of the revenues from exports. With increases in the price of petroleum, the nation has been experiencing a significant economic recovery in recent years. This combination of oil price increases and the positive economic moves of the Chávez government have helped to move Venezuela's economy out of the stagnation of the 1990s without bringing on a monetary crisis. Under the requirements of the new constitution, which he largely drafted, Hugo Chávez was reelected as president for a term of six more years.

The Nature of the Audience: Literacy, Affluence, Population Distribution, Language Distribution

During the oil and industrial boom years of the 1960s through 1980s, the population of Venezuela became increasingly urbanized with thousands of people migrating to the cities of Maracaibo, Coro, and Caracas in search of work. By the mid-1970s, Venezuela had surpassed Argentina as the most urbanized of South American nations. According to the 1995 census, the population of the nation stood at 21.3 million. Of this, 85 percent live in the large cities where population growth is a combined result of high birthrate, migration from rural areas, and immigration from abroad. In 2002, five Venezuelan cities, Caracas (3.5 million), Maracaibo (1.9 million), Valencia (1.7 million), Maracay (1.1 million), and Barquisimeto (1.0 million) boasted urban-area populations over one million and accounted for 43 percent of the nation's population. The result of this urbanization has been an improvement in the ability of print and broadcast media providers to reach a large percentage of the population with their messages.

The benefits that urbanization has brought in terms of ease of communication are offset by social problems. Municipal services have not possessed the funding or the expertise to meet the demands placed upon them by the influx of residents and the rapid expansion of their developed areas. Millions of people in the major cities live in large communities of sub-standard housing, while millions more occupy sprawling areas of single-family homes that have sprung up without the benefit of zoning, code enforcement, or planning. These problems and the other social problems that typically follow in the wake of urbanization and poverty have created a growing social awareness both among the people and among the organs of journalism.

Race does not play a significant role in Venezuelan life as most of the people are a mix of European, African, and Native American ancestry. The people typically consider themselves to be a single ethnic group despite visible differences that might create rifts elsewhere in the world. This unity derives from a common culture based on the Hispanic history of the region and augmented by African and Native American influences that have been effectively absorbed into the mainstream. Another source for the nation's sense of ethnic unity is the predominance of the Roman Catholic church, which accounts for 95 percent of the population in identification if not in practice. In recent years, a small but growing number of Protestants, Mormons, and other new religions have begun to influence if not convert the population.

Much more divisive than race and ethnicity in Venezuelan culture is the force of economic stratification. The nation's per capita gross national product stood at $3,020 in 1996, a figure that was declining mostly due to weak oil prices. During that same year, urban households in the bottom quintile earned 5,267 bolivares (approximately US$7.50) per month while those in the top quintile earned 74,261 bolivares (approximately US$106) monthly. The top 20 percent of the working populace accounts for 52 percent of household income. With such a small group of very wealthy persons and a huge mass of chronically and severely poor, Venezuela's income distribution is similar to that of traditionally wealthy yet politically corrupt nations of Africa and Asia and considerably more skewed than the United States and United Kingdom.

For many years, the media has essentially ignored the economic disparities present within the Venezuelan culture, portraying the entire nation as a homogenous, upper-middle class group. While this portrayal appeals to those in the economic levels that advertisers seek to reach, it leads to chronic dissatisfaction among the poorer classes. Just as the economic disparity creates feelings of resentment, regional biases within the media present a skewed picture of the nation. With most media outlets based in Caracas, the focus of the media falls largely on the capital and to a lesser degree on the other large metropolitan areas, especially Maracaibo. Regional radio stations and daily newspapers provide some coverage of the outlying areas, but the picture presented by both print and broadcast media is overwhelmingly one of Caracas.

Literacy in Venezuela stood at 91 percent in 1996, according to a World Bank Human Development Report. This level of literacy, comparable to those of Singapore and Colombia, placed the nation at number 32 among the 98 countries studied. Perhaps more significant, the literacy rate rose by 21.33 percent over the years 1970-1995, indicating that educational efforts of recent decades are creating a more literate populace with greater access to print media.

Historical Traditions

The first newspaper published in Venezuela appeared more than a decade before the nation achieved independence from Spain. The Gaceta de Caracas appeared in 1808 and established a tradition of relative freedom for the press. Given the area's distance, both physical and cultural, from the imperial stronghold in Bogotá, Colombia, democratic ideals and press freedom flourished in this region, especially as compared with the levels of freedom achieved in the other parts of Latin America.

Despite the long-standing desire of many Venezuelans to achieve the establishment of a truly open and democratic state, a tradition that includes the nation's pride as the birthplace of Simón Bolivar, Venezuela has, like many South American states, suffered under the rule of a progression of military and civilian authoritarian regimes. After the discovery of oil near Maracaibo, Venezuela quickly became among the world's largest producers of oil by the 1920s, a condition that has provided an impetus toward both openness and corruption.

Following the 1958 overthrow of dictator Marcos Pérez Jiménez, this progression of dictators was broken for nearly four decades. Press freedom came slowly and not without obstacles during the 1960s. Due to both the political instability in Venezuela and the effects wrought by the Castro regime's attempts to export communism from Cuba throughout the Caribbean basin, the government found itself responding to conflicting stimuli by struggling to create a more open society while at the same time attempting to stem subversive elements. During the early 1960s, the government attacked communists and other political movements deemed to be a threat to the nation's newfound democratic ideals. In the course of these attacks, the government placed various impediments in the way of opposition publishing organs.

In 1963, Betancourt's government went so far as to outlaw the communist parties and shut down their media outlets. Through the remaining years of that decade and into the 1970s, the government, while relaxing restrictions on mainstream media, continued to attack threatening parties, especially in their capacity to effect media distribution. By the late 1970s, the politically extremist press had been effectively silenced, leaving only a relatively benign opposition expressed in the mainstream press to provide a contrast to government positions. At this point the government began to relax restrictions on communist and other opposition media usage; however, by this time, the democratic state and moderate press tradition had been developed fully enough that the subversive elements had largely ceased to threaten the status quo.

The constitution of 1961, ratified three years after the restoration of democratic rule in 1958, provided press freedom in its Article 66, which states that all citizens have the right to express their thoughts through the spoken word and the written word, using all available methods of distribution to spread these thoughts without being subject to prior censorship. However, this same article provides for punishment to be assessed against "statements that constitute criminal offenses." Also outlawed are materials deemed to be propaganda which serves to incite the public to disobey the law. These exceptions to the press freedom provisions of the constitution allow for a wide amount of latitude in interpretation, a flexibility that provided the governments of the nation's early democratic period with opportunities to control unwelcome reporting. Even before the ratification of the constitution, early democratic governments used its provisions to restrain free expression in pursuit of what they deemed to be the national interest. The most significant use of this power came in 1961 and 1962 during the prolonged crisis between the elected government of Rómulo Betancourt and the forces of the Young Communists and other communist groups. During this period, Betancourt suspended the constitutional provisions for a period of fourteen months and outlawed the media work of the Communist Party. Even after press restrictions were relaxed in 1962, the government pursued a policy of eliminating extremist—especially leftist—elements from the established press, a process that continued throughout the 1960s. In response to these government moves, the remaining representatives of the press established a tacit agreement on standards, which has allowed them a maximum degree of free expression while at the same time avoiding in most cases the wrath and interference of the government.

During the economic prosperity brought about by a major increase in oil revenues and the political stability that characterized the 1970s in Venezuela, press freedom reached a level unparalleled throughout the nation's history. Even before the advent of democracy in 1958, oil revenue provided the dictatorial regimes with the funds to pursue significant programs expanding the social services infrastructure and attracting industry to the country. Improvements in the educational system raised the literacy rate in Venezuela from 77 percent in 1971 to 91 percent in 1995. This increase is accentuated by the fact that the numbers of illiterate citizens fall largely in older age groups, suggesting that over time, current efforts will see this number rise as the population moves through the school system. The result of these programs was the creation of a pool of better educated, healthier, and more highly skilled workers who eventually formed a larger middle class than might be found in other Latin American nations at that time. This class shift is widely credited with providing an impetus toward democratic rule.

In 1979, the government made assurances to the Inter-American Press Association that it would not assert control or regulatory power over the nation's private press, yet such control and regulation have always been in force to some degree, if only in the form of both legal stipulations and extra-legal practices. While each of the nation's constitutions has provided for freedom of the press, they have all likewise placed the obligation upon the members of the press to uphold standards agreed upon by the citizens and requiring them to serve as a national resource.

Having for many years walked a difficult line between reporting the news and avoiding government censorship and sanctions, the press found that as the economic outlook brightened and the political situation relaxed, their ability to report openly on items unfavorable to those in power improved. In 1980, for the first time, the press began to challenge government positions and criticize policy failures. At the same time, the increase in economic activity diluted the power of government advertisements in the media as more private-industry advertisements found their way into the media outlets.

As in many nations, the influence of the press, especially television, has long been contested in Venezuela. In 1980, the government banned the advertisement of tobacco and alcohol products on television in an effort to counter the perceived message that the use of these substances was essential to social and economic success. These new regulations, which were imposed as part of a package of new policies that accompanied the introduction of color broadcasting to the nation's television outlets, codified the long-held position that the national media, particularly the broadcast media, bore a public obligation to serve the larger good and to work in cooperation with the government to improve social conditions. As a continuation of this policy and attitude, a set of standards for regulating the level of violence and sex in television programs found its way into law in the early 1980s. Since that time, programming that is perceived to run counter to widely accepted national values does not clear the ratings office and thus is not permitted on the air.

Perhaps as a result of years of attempting to coexist with the political vagaries and dictatorial regimes of the nation, news reporting in Venezuela has traditionally been characterized by a stiff and unimaginative style. The word most commonly applied to reporters, cronistas , signifies their perceived role much more as relaters of facts than as interpreters of the events of the day.

Owing largely to a history that involves the coexistence of governments brought about by the nation's shifting political landscape, the Venezuelan media can be accurately described as nonpartisan in their handling of news stories. Given their dependence on government li-censure for continued existence, the broadcast media are probably the most strictly held to a policy of neutrality. Since the beginning of broadcasting in the country, news programs have been brief and factual. In recent years, more news analysis programming has found its way onto the airwaves, although the volume and the editorial liberty of these programs are not nearly as great as their counterpart programs in the United States and Europe. The print media, forced to abandon the publication of editorial opinions during the dictatorial regimes of the 1950s and before, avoided for many years the resumption of this practice. Although the major news dailies have all reintroduced editorial pages, the tenor of the opinions expressed in these editorials tends to remain restrained by comparison with those of comparable newspapers in other countries. One of the hallmarks of Venezuelan editorial pages is the general absence of journalistic reports. Rather than filling their columns with the work of an editorial board, Venezuelan op-ed editors surrender that space to politicians, academic figures, business leaders, activists, and other guest columnists. Invariably signed and affiliated with political parties or public positions, the authors of these editorials interject a wide variety of opinions into the newspaper without involving the editors of the publication directly. This practice, of course, is not as unbiased as it might appear on the surface. Editors still oversee the tenor and content of their pages through their selection of writers, a practice which allows the El Universal to create an opinion page as right-leaning as that of the Wall Street Journal , while El Nacional creates a page as biased to the left as the New York Times .

In October 2000, the International Press Institute included Venezuela on their "Watch List" of nations in which the freedom of the press stood at risk due to the repressive actions of the government. At that time, the same organization accused President Chávez of failing to oppose hostile actions directed at the press.

The press situation in Venezuela has two faces. On the exterior, freedom of expression exists, at least legally. However, on the interior, journalists constantly suffer from government repression aimed at eliminating all reporting critical of the official positions. The publication Press Freedom Survey 2000 , created by Freedom House, concluded that the press in Venezuela was only partially free. Their criticism took particular exception with the October 1999 passage of constitutional article 59, which most in the press saw as a license for government censorship. The survey also notes that in November 1999, after reporters at Radio Guadalupana broadcast an editorial that criticized the policies and leadership of President Chávez, government intelligence officers appeared at the station and warned the staff that its further broadcasts would be monitored. That same December, explosive devices were discovered in the building that houses offices for several press organizations including the Associated Press, Agence France Presse , and the daily newspaper El Universal .

As critical as the Press Freedom Survey 2000 and other press watchdog groups have been toward Chávez, the situation must be viewed in perspective. The 2000 survey awarded Venezuela a score of 34 out of a possible 100. Nations scoring below 30 are considered to have a free press. Therefore, it was fair to assert at that time that the situation in Venezuela, while not as free as in previous years, was not as yet grave. In 1999, the International Federation of Journalists reported 312 cases of press harassment in Latin America, including 55 cases in Colombia, 126 in Peru, and 21 in Argentina. Venezuela, by contrast, reported only one case. The 2002 Press Freedom Survey , however, reflected a continued downward trend, with the revised score of 44 and mention of various government actions aimed at controlling the reporting of unfavorable news.

Newspapers

According to the World Bank's 1994 data, newspaper circulation in Venezuela totals 215 papers per 1,000 people, which ranks the nation 29th among the 106 for which the data are available. This figure places Venezuela just behind the United States (228/ 1,000) and just ahead of Canada (189/1,000) in newspaper circulation. The same data indicated that the nation owns 180 televisions per 1,000 population, a figure which places Venezuela at number 69 among the 127 countries available.

The two most influential newspapers in the nation are undoubtedly the two leading Caracas dailies, El Universal and El Nacional , with Maracaibo's primary dailies, Panorama and La Verdad placing a close third and fourth in influence. Most observers agree that the most important newspaper in Venezuela is the more conservative and business-oriented El Universal although the difference between this paper and its more liberal rival El Nacional is slight. The product of a creative liaison between poet Andrés Mata and the writer and lawyer Andrés Jorge Vigas, El Universal first appeared in April 1909. In 1914, the newspaper became the first in Venezuela to make use of international services, initially carrying the offerings from Cable Francés and UPI. In later years, Reuters, Wolf, and the Associated Press were added. Published in Caracas and distributed nationally, the newspaper offers editorials and covers national and international news, arts, business, politics, sports, and entertainment in its daily editions.

Although published in Caracas, El Universal is a truly national newspaper. Through the mid-1980s, the newspaper published from a single press in Caracas and made use of an extensive and efficient air distribution system to reach a vast majority of the nation's population in a timely fashion. With the development of less expensive printing facilities and better capability to transmit editions electronically, the air distribution network has been largely superseded by a series of provincial printing installations. The national editions of El Universal are published at 6:30 am each day from 32 regional distribution points and from there carried by truck to final distribution points, placing the paper within reach of more than 90 percent of its potential readership. El Universal maintains a circulation of approximately 150,000. In October 1995, El Universal began to complement its print edition with an Internet-based edition.

The nation's second most important newspaper is El Nacional , which like El Universal is published in Caracas. This newspaper, like its main rival, carries national as well as international news along with editorials, sports coverage, features, lifestyle coverage, political reporting, and obituaries.

Outside of the capital, the most influential newspapers are Maracaibo's twin dailies, Panorama and La Verdad , which both feature politics, local and national news, business, and sports coverage. Panorama , established in 1914, features national and regional news, including politics, economic coverage, and a regular section on the petroleum industry. Rounding out the newspaper are sections for opinion, sports, culture, and lifestyle. Panorama , the more conservative of the two Maracaibo-based dailies, has long been considered one of the most prestigious news sources in the nation and serves an elite readership spread throughout the nation.

Other regional newspapers of note include two Valencia-based dailies El Carabobeño , a centrist daily, and Notitarde. La Nación from San Cristóbal, El Impulso from Barquisimeto, Últimas Noticias , an independent daily based in Caracas, and El Tiempo , a Puerto Cruz-based daily independent round out the list of leading newspapers. The newest significant player in the Venezuelan newspaper market is Tal Cual , a daily tabloid, founded in April 2000 by Teodoro Petkoff, the former director of the daily El Mundo . Tal Cual combines a vigorous writing style with a colorful and informal layout to create a newspaper that is probably the most visually intriguing in the crowded Caracas scene.

In recent years, following the lead of North American newspapers, Venezuelan dailies have begun to move away from a strictly text-based format to one in which visual communication is far more important. In 2000, the Maracaibo-based Panorama effected a major design overhaul with the aid of a team of American graphic designers.

Press Laws

Constitutional Provisions & Guarantees Relating to Media

The current constitution of Venezuela was approved by the Constitutional Assembly on December 15, 1999 by 71 percent of voters. Article 57 of this document guarantees Venezuelans the "Right to the free expression of thoughts," while Article 59 promises the right to access needful information, true and impartial, without censorship.

Article 59 of the constitution decrees that all Venezuelans possess the "right to timely, truthful, impartial, and uncensored information." Free-press advocates fear that the adjectives, "timely, truthful, and impartial" might be used as a pretext to punish or silence opinion columns and political analysis deemed to be based more on conjecture than on verifiable fact. President Hugh Chávez, the primary author of the new constitution, brought to his office a history of criticism for free-press groups. In the build-up to the referendum campaign on the constitution, he publicly proclaimed the president and executive director of the Paris-based Reporters Without Borders organization as scoundrels, largely as a result of their opposition to Article 59.

As of 2002, Article 59 had not been used as a pretext for the application of censorship or restriction upon the nation's press; however, various other methods, legal and otherwise, had been used by the government in order to assert greater control over the press. One clear example of this repression is seen in the sentence approved by the Tribunal Supremo de Justicia , Venezuela's highest court, in June 2001. In this decision, the court deprived the right of reply to the journalist Elías Santana of the magazine La Razón as a result of his writings critical of government policies.

Summary of Press Laws in Force

While the most significant legal force concerning journalists is the 1999 constitution, a pre-Chávez law on the practice of journalism remains troubling for many in the press. Since its imposition by the government in December of 1994, the new journalism law has been opposed by most of the publishers in Venezuela. The major effect of this law created additional difficulty for journalists seeking to obtain licenses. The penalties for the illegal and unlicensed practice of journalism under this law included imprisonment. President Rafael Caldera, the principal architect of the legislation, expressed outrage at the criticism leveled against his government from both domestic and international press representatives; however, the hostile reaction from representatives of the press have been nearly universal.

Censorship

Censorship in the strictest sense has been exceptionally rare throughout Venezuelan history. Even under the control of the most repressive regimes, the government tended to take other approaches to media control rather than directly censor its work. In some cases, especially early in the nation's democratic period, certain journalists with politically extreme positions were essentially run out of their professions, but direct censorship, even during the Chávez years, remains rare. Although many critics point to the inauguration of Hugo Chávez as the point at which press-state relationships began to worsen, tension had actually been mounting throughout the 1990s.

In 1923, in response to a perception that it was serving as a conduit to distribute North American propaganda, the Maracaibo-based Panorama newspaper was closed by General Juan Vicente Gómez, the dictator who controlled the nation for 27 years. In a 163-word pronouncement, Gómez closed the daily and sent its editor, Ramón Villasmil, to prison. The paper remained closed for eight years, resuming publication in 1931, four years before the death of Gómez.

During the 1970s, the director of the news weekly Resumen continually incurred the wrath of the government when he ran a series of articles that were extremely critical of the president. In 1978, this criticism crossed the line that the government would tolerate when the magazine printed an article that accused the president of enriching himself by accepting bribes and kickbacks. The government acted against Resumen by confiscating the entire run of that issue of the magazine.

Article 57 of the 1999 Constitution provides for censorship in certain cases, which include anonymous authorship, war propaganda, and messages that promote discrimination or religious intolerance. This position was upheld by the nation's Supreme Court in their Decision 1013 on the Santana "Right of Reply" case in June 2001.

State-Press Relations

Since the December 1998 democratic election of Hugo Chávez as president of the República Bolivariana de Venezuela, relations between the government and the press have been strained and are generally considered to be deteriorating.

In June 2001, the Venezuelan Supreme Court passed down a decision through which they defined the criteria for the "timely, truthful and impartial information" clause in the 1999 Constitution's Article 58. The court's Decision 1013 put an end to the petition of Elías Santana, an activist in an anti-Chávez civic group Queremos Elegir ("We Want to Choose"), for his right to reply to the attacks leveled by Chávez on his radio show. In their ruling, the justices determined that while the constitution does make provision for a right to reply, this right was intended solely to benefit citizens who do not possess access to regular public forums. The court decreed that those in the media must take pains to avoid spreading "false news or news that is manipulated by the use of half truths; disinformation that denies the opportunity to know the reality of the news; and speculation or biased information to obtain a specific goal against someone or something." Santana, as a result of his work as a columnist for the national daily El Nacional , as well as other media professionals would not be protected by this provision.

The Court also ruled that journalists, while free to express their opinions, may not do so if these opinions include ad hominem attacks or irrelevant or unnecessary information. Publications, the court added, may be found in violation of the law if the majority of their editorials tended toward the same ideological position without that position being publicly stated by the periodical. Press freedom advocates both within Venezuela and overseas criticized the court's ruling as overly broad and open to manipulation by government officials bent on suppressing unwelcome coverage.

Many observers have noted the considerable irony in Chávez's hostility toward the press, as the President is a creature of the media. Chávez had been completely unknown when, on Feb. 4, 1992, he took the lead in a coup against the detested but popularly elected government of the time. Before the army suppressed the coup, Chávez appeared on national television and attacked the onset of moral and economic decay that he claimed threatened the future of the nation. Although his coup failed, Chávez became an instant hero in the minds of many, especially the poorer classes.

When he ran for president in 1998, Chávez could ascribe no small part of his rehabilitation to a wealth of sympathetic interviewers, especially in the broadcast media. The platform that Chávez spelled out for the nation promised nothing less than a complete revolution, although one made peacefully and by democratic means. The presidential campaign, pitting the gruff and unsophisticated Chávez versus a stunning blond former Miss Universe, proved a perfect televised spectacle. Playing on the visual contrast, Chávez presented himself as the strong and capable leader that the nation required, a strategy that played well in a country with a macho image and a desire for forceful leadership.

While the broadcast media helped to create Chávez, the print media remained opposed to him. Part of the explanation for this split lies in the audiences reached by the two media. The press was also put off by the style with which Chávez presented himself. They found him to bring a militaristic mindset to ideas such as education and macroeconomic policy. However, many print journalists had philosophical reasons for their opposition. Many of them stated that it was inappropriate for a coup leader to run for president.

In January of 2002, press-state relationships festered into a peculiar series of events that eventually unseated, replaced and then reseated Hugo Chávez as president. The constitutional crisis began simply enough as Chávez visited a poor neighborhood in Caracas. There, the president found himself greeted not as a hero of the poor but as a failed tyrant. The women of that neighborhood employed a traditional form of peaceful protest, the cacerolazo , in which they beat loudly on pots and pans. This same form of protest had been at the heart of the removal from office of Argentina's President Fernando de la Rua in December 2001. When the highly respected national daily El Nacional published a brief report of this protest the next day, the party of the president acted swiftly. They moved quickly to organize a "spontaneous" demonstration that placed party members and government workers outside the newspaper's offices for four hours of harassment that included rushing the doors, throwing stones, and shouting at workers. El Nacional Editor Miguel Otero quickly accused the government of inciting the demonstration to "keep the press from publishing what is going on in the country." The demonstration earned immediate condemnation from the Catholic church, the United States State Department, and the mayor of Caracas.

Organization & Functions of Information Ministry/Department

The 1961 constitution created the nation's Ministry of Communications, a department charged with the creation and maintenance of laws pertaining to standards and practices in the broadcast media. This ministry evolved into the Comisión Nacional de Telecomunicaciones (CONATEL). CONATEL maintains oversight over all licensure and standards enforcement for radio and television broadcasting as well as oversight of the nation's cable television providers. The agency listed well over 700 television stations broadcasting across the country in 2002. This list includes 144 UHF stations with the balance broadcasting on VHF frequencies. In the Federal District that surrounds Caracas, the largest market in the nation, 40 separate stations are listed. The nation's television signal is distributed by approximately 200 cable television providers. CONATEL's list named 186 AM and 433 FM radio stations in service in 2002.

Managed News

On June 17, 1999, six months after taking office, President Chávez announced the creation of a daily newspaper, El Correo del Presidente (The President's Mail). Prior to the creation of this periodical, the president submitted the majority of his ideas directly to the public press, depending therefore on channels of communications that were increasingly not open to his political leanings. In an effort to counteract what he perceived to be unjust coverage from the media, both domestic and international, Chávez also launched an English-language version of his newspaper for sale abroad.

A year after the creation of his daily newspaper, El Correo del Presidente , President Chávez initiated a television program, De Frente con el Presidente , that airs on the state television channel, Venezolana de Televisión . As a companion piece to his newspaper, De Frente is used by the government for the promotion of various positions and policies that might not be covered favorably in the private press. In addition to the television program, Chávez also hosts a radio program titled Aló Presidente , which is transmitted every Sunday on the Radio Nacional network. One example of Chávez' use of this radio time is in his constant criticism of the journalist Elías Santana, whose anti-government posture he attacked and whom he marginalized as a representative of the most petty sector of civil society. When Santana, who listened to the program, spoke with representatives of Radio Nacional in order to make use of his right to reply, he was never answered by the station. After various legal attempts, the Venezuelan high court decreed that Santana held no such right.

In July 2000, only a few days before the national election, the nation's National Electoral Council issued a decree barring Chávez from the possible illegal use of his program for the promotion of his electoral campaign. In the end, however, Chávez skirted the order and Venezolana de Televisión broadcast a personal speech by the president in which he attacked his political opponents. Radio Nacional , on the other hand, refused to air three electoral advertisements on behalf of the president.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

The procedure for foreign correspondents wishing to work in Venezuela has long been simple. In order to work for foreign publications from within the nation, journalists must simply apply for a visa, a process that is normally automatic. The nation's Ministry of Work maintains a tight control on the hiring of foreign journalists by Venezuelan press entities. The laws which require all working journalists to belong to the journalists' colegio apply equally to foreign correspondents.

Prior to 1973, no Venezuelan media outlets supported reporters abroad. By 1980, all of the most prestigious dailies had established foreign bureaus, a practice that has expanded in the intervening years. The leading broadcast news outlets similarly either support foreign correspondents or maintain contractual employees from among the freelance press in those nations.

In June 2001, President Chávez announced that he had given orders that any foreigners, journalists or others, who made remarks critical of the country, the President, or the armed forces would be expelled from the country for interfering in domestic politics. These remarks came just days after a politician from Peru drew a comparison between Chávez and former Peruvian president Alberto Fujimori. To date, no reports of this order being enforced have been made.

Aside from occasional problems with the foreign press, the government generally allows a free flow of information into the country from abroad. Many international newspapers and magazines are available, especially in the capital. Broadcast media are especially saturated with foreign, primarily American, offerings. The programming schedules of all of the television networks feature foreign programs ranging anywhere from 10 percent (in the case of Globovision) to nearly 50 percent (in the case of Televen and RCTV).

Foreign Ownership of Domestic Media

The government acted in 1974 to force all foreign investors to sell their interests in excess of 20 percent ownership in all Venezuelan broadcast media, an action paralleled in various other business groups. This policy was aimed more at gaining domestic control of Venezuelan business interests than at ensuring domestic control of the media's output. In recent years, various broadcast entities within the country have created partnerships with international media providers. The most noteworthy example of this is the media empire that has been created by the Cisneros family. Not only does the Cisneros media group of companies provide Venezuelan partnership for such North American entities as AOL-Time Warner and DirectTV, but they have taken immense amounts of capital and invested internationally, becoming key investors in various broadcasting ventures, most notably the North American Spanish-language giant Univision.

News Agencies

The largest news agency in Venezuela is Venpres. Created in May 1977 in order to serve the Ministry of Information and Tourism, they collect, develop and distribute news from among the many government ministries to the various media. In 1990, Venpres was advanced to the level of a full government agency, the Agency of National and International News reporting to the Central Information Office. The agency maintains 70 reporters and correspondents spread among the principal cities of the nation and charged with projecting the "true image" of Venezuela throughout the world. The services of the agency include daily news summaries, periodic complete news stories, an official newsmagazine, and periodic special features.

Moving far beyond their original charge as an agency responsible for the coverage and synthesis of the information generated by the various government agencies, Venpres functions as a fully rounded news provider with coverage of politics, national and international news, economic matters, culture, science, and sports.

Given the current strained relationship between press and state in Venezuela, it should not be forgotten that Venpres remains a government organ ultimately answering to the President. While not a completely independent entity, however, Venpres has demonstrated that it is not simply a propaganda organ. For example, the coverage of the activities of April 2002 during which President Hugo Chávez was removed and then restored to office, did not hide the chaos and violence within the streets of Caracas. A gallery of photos displayed on the agency's website shows the actions of law enforcement as well as wounded civilians receiving medical assistance. It displays loyalists as well as prominent protestors. While it might be argued that Venpres portrayed the military and police who acted against demonstrators in an overly heroic manner, the coverage could not be described as a whitewash in any sense.

Despite their generally good reputation, the editors at Venpres have been used by the state for its purposes. In March 2002, an article offered by Venpres to its subscribers and published on its website, accused three journalists (Ibéyise Pacheco, director of the Caracas newspaper Así es la Noticia; Patricia Poleo, director of the daily El Nuevo País; and José Domingo Blanco, an on-air personality for the television news channel Globovisión ) of being in the pay of international drug cartels for the purpose of damaging the reputation of the Venezuelan government. While no evidence accompanied the article to prove the connection, all three journalists have a long record of criticizing the president. The director of Venpres, Oscar Navas Tortolero, offered to resign in the wake of the article's adverse consequences.

Venpres also supports an international service, cooperating with the corresponding agencies in several other countries and with the broader Prensa Latina and International Press Service. The government uses its Venpres services to provide information through its embassies and consulates to governments and media outlets around the world.

Broadcast Media

Television

Television services, like radio, are divided among both government and privately operated systems. Two government organizations broadcast nationwide. Venezolana de Television is a government-run station providing programming on channels five and eight. Televisora Nacional is a smaller government-run television service.

Several private television services provide programming regionally and nationwide. NCTV, a Maracaibo-based private station and Venevision, a private channel served by nineteen relay stations, both provide programming nationwide. Televisora Andina de Merida (TAM) provides another private channel and focuses its coverage on the interior of the nation.

Venevision, with RCTV (Radio Caracas Television), the most important broadcasting outlet in Venezuela, began broadcasting in 1953 but took its present place of importance after being purchased by Don Diego Cisneros at the behest of then-president Rómulo Betancourt. The network provides daily news and news analysis programming. The network's news shows are broadcast on week-days at 5:45 am, noon, and 11:00 pm and feature national and international news along with coverage of cultural and sports matters. Venevision also is the Venezuelan outlet for BBC World Service programming as well as Univision's news service. The news analysis and opinion programming on Venevision ranges from a 48 Hours -style news magazine, 24 Horas , through interview programs such as Dominio Público and Vox Populi , to an On the Road with Charles Kurralt -style program, Así Son Las Cosas with Oscar Vanes.

RCTV, a privately-owned and operated Caracas-based channel, uses 13 relay stations to provide television service to virtually the entire nation. The earliest of the private television outlets, RCTV was created on November 15, 1953 by William H. Phelps, who created a television counterpart for the most influential of Venezuelan radio networks, Radio Caracas Radio. News coverage, led by Francisco Amado Pemía, began on the second day of broadcast from the new network. This first news program, El Observador Creole , continued news coverage over the space of 20 years. As time passed, RCTV prided itself on remaining on the vanguard of broadcast journalism. In 1969, they were the only Venezuelan television outlet capable of broadcasting live the Apollo XI moon landing.

Currently, RCTV's news department provides coverage of national and international news as well as financial markets, art and entertainment, fashion, and sports through their news program, El Observador . Appearing on RCTV weekly is a news magazine program, Ají Picante , that mixes a heavy dose of celebrity personality with topics drawn from sports, society, politics, and entertainment. La Entrevista de El Observador is an interview program appearing six mornings each week.

Televen came into existence in 1988 when a group of independent producers and television professionals came together to create a network that would be, in their words, "dignified, responsible, creative, innovative, and of high quality." From the beginning, Televen attempted to conjoin entertainment and information, although its early years leaned decidedly to the entertainment side of the equation. In 1994, Televen began to provide 24-hour programming, filling much of the new airtime with news and information programming. Currently, the network provides 30-minute news programs twice each weekday, at 8:00 am and 10:30 pm. Two hour-long news analysis programs, La Entrevista and Triángulo , are aired from 6:00 am until 8:00 am. At 10:00 pm every weekday a news opinion and analysis program, 30 Minutes , is aired.

Globovision, broadcasting since 1994 from Caracas, serves as the CNN of Venezuela. Throughout the day, Globovision provides a variety of news feeds in 15-and 30-minute increments. Globovision's news programming includes its own reporting as well as that from TV Española, Euronews , RCN (Colombia), and CNN. The network provides several news opinion programs throughout its broadcast schedule. These include Primera Página , a Nightline -style program focusing on the most important news stories of the day; En Vivo , focusing on the development of national life; Debate , in which various views on pressing issues of the day are argued, allowing the viewer to "form your own conclusion"; Yo Prometo , which focuses on the electoral process; Otra Visión , a program discussing the productivity of the nation; Cuentas Claras , an economic affairs program; Sin Máscara , a program that aims to expose events without "makeup"; and Reporteros , a Sunday press-review program.

PromarTV provides considerably less news programming than the other networks. Broadcasting out of the regional city of Barquisimeto, Promar provides a daily news program, El Gobierno es Noticia , which is most noteworthy for its emphasis on west-central regional news. Sin Barreras , a news opinion program, has experienced considerable success in its short run. The other

American cable networks such as Warner, Sony, Bravo, and HBO also maintain a strong, although mostly entertainment-oriented, presence in Venezuela. Television services have expanded dramatically over the past several decades. In 1994, owing to the difficult economic times and government takeover of many banks, television suffered a critical period with advertising revenues falling off sharply. The devaluation of the currency by nearly 40 percent has created a very difficult credit market and made the importation of international programming economically unfeasible.

With the increasing market for Spanish-language television, Venezuela, long an importer of American programming, has found itself a lucrative export market in the Spanish cable networks that serve North America. In 2001, Spanish-language cable giant Univision closed a contract with Venezuela's RCTV through which RCTV will provide 800 hours of original programming each year over the 10-year term of the contract. In this same deal, Univision gained access to RCTV's library of past work that has not yet aired in the United States.

Radio

Many different radio providers, ranging from large nationwide networks to individual stations serve Venezuela: Circuito Éxitos, Unión Radio Noticias , Z100 FM, Victoria, El Templo , and others. The most important news radio provider in Venezuela is Unión Radio Noticias , which provides 24-hour news and information when it is not broadcasting sporting events. Besides three one-hour blocks of daily newscasts at 7:00 am, noon, and 5:30 pm, URN provides original programming for another 12 hours each weekday. These programs include call-in public affairs programs and interview shows. On the weekends, the programming becomes considerably lighter with many programs devoted to lifestyle matters, entertainment, and sports. Along with its considerable original programming, URN serves as a source for both the BBC World Service and CNN Radio news. This network has been widely recognized for excellence in broadcasting, including being awarded the Premio Nacional de Periodísmo (National Journalism Prize) in 1997, 1998, and 2000.

Ownership

With a beginning at Venevision, Diego Cisneros expanded his media holdings across the Spanish-language broadcast and entertainment industry. At present the Cisneros Group of Companies owns outright or maintains a major interest in broadcasting outlets in Chile and Colombia. They are the major stockholders in the Spanish-language cable giant Univision and are partners with AOL-Time Warner in AOL Latin America. In Venezuela, the Cisneros Group has expanded from the Venevision flagship to a Venevision Continental product designed for sale across South America and Vale TV, a values education project dedicated to the nation's youth.

Electronic News Media

Internet Press Sites

Most of the large press organizations in Venezuela support thorough and professionally maintained Internet sites. All of the major Caracas-based television networks provide significant news coverage on their websites, as do the major dailies, except, at the time of this writing, El Nacional . These sites strongly resemble both in design and content the newspaper sites of many dailies in the United States. The Caracas tabloid Tal Cual , a newcomer to the Venezuelan news scene, not only places all of its content online, but allows readers to view page layouts of the print edition of the newspaper over the past week of issues. Tal Cual is also unique in extensively utilizing audio files in their Internet offerings. All of the sites provide access to at least six months of archived stories and allow flexible searching. Venpres, the government-run news agency maintains a similarly thorough Internet site.

Restrictions on access to the Internet do not exist within Venezuela. Although the access currently available tends to be rather expensive to the population in general, each year has seen more of the public gaining access to this medium of communication. The nation depends on various Internet providers based both with the nation and abroad.

Education & Training

The Venezuelan journalism colegio requires that practicing journalists hold a degree in journalism. Because of this requirement, journalism education is viewed with increased significance. Many critics complain about the quality of journalism education at the nation's universities, noting that these schools have not remained current with the shifting world of information-gathering or the introduction of new and changed media.

The two most important journalism programs in Venezuela are those at the Universidad Central de Venezuela in Caracas and at the Andrés Bello Catholic University, also in Caracas. The program of study in journalism at these universities spans ten semesters. Typically the first six of these semesters place all students in a common track while the final four allow each student to specialize in one of three areas of emphasis: broadcasting, public relations, and print journalism. This course of study leads to a bachelor's degree in Social Communication. The two Caracas universities also offer post-graduate education leading to a Specialist degree. Four-year journalism degrees are also offered at two regional universities: the University of Zulia in Maracaibo and the University of the Andes. Tuition at the state schools is free to all qualified students; however, the capacity of the state universities is not sufficient to meet the demand.

Major Journalistic Associations & Organizations

In 1972, the nation's Law of Journalism established Venezuela's colegio , to which all practicing journalists must belong. The law also sets the standards and guidelines according to which journalists should work. Media owners typically oppose the power of the colegio , while working journalists generally support it.

Summary

The future of the media in Venezuela depends heavily on the actions and policies of President Hugo Chávez. In April 2002, Chávez was apparently ousted from office by a combined popular-military coup only to be reinstated a few days later. At the time of this writing, the possibility of significant change in relations between press and government in the near future appears quite high. The "new start" promised by Chávez after the failed coup of April 2002 remains too brief to be fairly evaluated at the time of this writing.

Venezuela's government has been given the tools with which to effectively silence opposition voices in the media through legal means. To date, the government has demonstrated restraint in using these tools, probably due to the nation's strong tradition of free expression. Instead, it has employed extra-legal tactics of intimidation. One of the key trends to observe in the future is the direction that the government takes in controlling information.

As is so often the case, future conditions in the Venezuelan media depend to a great degree on economic matters. Not only will economic success or failure determine the degree to which the government possesses the popular support necessary to maintain press control, but economic questions will dictate the levels of investment that media outlets will be able to make in exploiting new media and fully funding old ones. The complexity of the influences that the economic future of the nation can have on the openness and quality of the media makes predictions very difficult. Positive economic news might mean both good and bad times for the journalists of Venezuela.

With a solid democratic tradition among its people and a long history of solid journalism, most observers see a good deal of hope in the future for the Venezuelan press. Political and economic difficulties have waxed and waned over the past century, and the journalists of Venezuela have shown themselves capable of adapting to whatever situations the times present.

Significant Dates

- 1972: First Law of Journalism passed founding the journalism colegio .

- 1994: Second Law of Journalism passed by Caldera providing penalties for unlicensed reporting.

- 1998: Hugo Chávez Frias elected president.

- 1999: New Constitution ratified, including the controversial Article 58, which provides free, uncensored access to information that is necessary, true, and impartial. Press freedom advocates see this provision as an invitation to government censorship.

- 2000: Elias Santana, columnist for El Nacional , files suit against President Chávez after being denied a right of reply to accusations made on the president's weekly radio call-in program.

- 2001: Ruling 1013 by the Venezuelan Supreme Court denies journalists the right to reply while defining the provisions of constitutional Article 58 in terms very advantageous to the government.

- January 2002: Government organizes "spontaneous" demonstration against newspapers critical of the president.

- March 2002: Venpres accuses three journalists of accepting money from international drug cartels for the purpose of smearing the reputation of the Venezuelan government.

- April 2002: Thousands protest the government's continued harassment and attacks on media critical of his policies. Chávez is forced from office, replaced, and then returned to office promising a new start.

Bibliography

Annuario Estadistico . Caracas, annually.

Arias Cárdenas, Francisco J. La revolución bolivariana: de la guerrilla al militarismo: revelaciones del comandante Arias Cárdenas . Caracas, 2000.

Díaz Rangel, Eleazar. Prensa Venezolana en el Siglo XX . Caracas, 1994.

El Universal: 80 años de Periodismo en Venezuela ,1909-1989. Caracas, 1989.

Freilich, Miriam. Cara a cara con los periodistas . Caracas, 1990.

Nweihed, Kaldone G. Venezuela y— los países hemisféricos, ibéricos e hispano hablantes: por los 500 años del encuentro con la tierra de Gracia . Caracas, 2000.

Venezuela Country Report on Human Rights Practices for 1998 . U.S. Department of State. Washington, 1999.

Mark Browning