Afghanistan

Basic Data

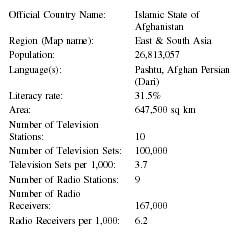

| Official Country Name: | Islamic State of Afghanistan |

| Region (Map name): | East & South Asia |

| Population: | 26,813,057 |

| Language(s): | Pashtu, Afghan Persian (Dari) |

| Literacy rate: | 31.5% |

| Area: | 647,500 sq km |

| Number of Television Stations: | 10 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 100,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 3.7 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 9 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 167,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 6.2 |

Background & General Characteristics

When the Taliban took control of the capital— Kabul—on September 26, 1996, the Islamic State of Afghanistan began a period of regulation regarded by many as the most restricted in the world. Five years later, shortly after September 11, 2001, when terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon destroyed the former and severely damaged the latter, these restrictions began to ease, largely as a result of U.S. "war" strikes against the Afghani-based Al Qaeda (The Base) terrorist group held responsible for the attack.

Afghanistan has a population of around 25 million people composed of two major ethnic groups, Pashtun (38 percent) and Tajik (25 percent); however, additional ethnic groups include Aimaq, Balulchis, Brahui, Hazaras, Nuristanis, Turkmens, and Uzbeks. Most people are Muslim (Sunni: 84 percent, Shi'a: 15 percent). Many speak one of the official state languages (Dari: 50 percent, Pashtu: 35 percent), although there are some 30 viable dialects, and the official language of the religious leadership is Arabic. Between 1996 and 2002, religious police enforced codes of conduct that imposed comprehensive constraints on females.

A paternalistic background dominates the role communications has played in the country. Up to the time of this publication, the industry may be characterized as small, state-controlled, and subject to heavy censorship by religious fundamentalists. In 2001 newspaper circulation rates were estimated by objective data-gathering sources to be operating at the 1-percent mark. The Taliban Ministry of Information and Culture maintained that more than a dozen daily newspapers existed under their regime. These state-owned organs featured Taliban official announcements, news of military victories, and criticism of any opposition. Because there were no newsstands, the papers were distributed largely to political/religious institutions.

Low readership, in addition to low circulation, characterizes this country's journalism. The potential newspaper audience is small because Afghanistan has a literacy rate thought to be among the lowest in Asia (around 31 percent, according to UNESCO estimates), although education is officially compulsory for children between the ages of 7 and 13. Few matriculate to any form of higher education.

Restricted press life and low readership levels extend backward well beyond the Taliban. In fact, only one period may have permitted the operation of truly independent journalism—the supposed decade of democracy (1963-73) under the rule of King Zahir Shah, Pakistan's last monarch who reigned from 1933 to 1973. With his overthrow, media restrictions increased geometrically under President Mohammad Daud (1973-78), the Communist People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (1978-92), the provincial Mujahidin (fighters in a holy war) (1992-96), and the Taliban (1996-2002).

The first regularly published Afghani newspaper was the Saraj-al-Akhbar ("Lamp of the News") debuting in 1911 and published in Afghani Persian (Dari), eight years before Afghanistan gained independence on August 19, 1919, from Great Britain. Founder Mahmud Tarzi was outspoken and opposed, among other things, the official position of friendship between Great Britain and Afghanistan. After King Shir Ali Khan died, the "Lamp" was replaced by Aman-i-Afghan ("Afghan Peace"). From that initial period of attempted enlightenment until the 1950s through 1970s, when professional journalists facilitated a brief period of growth, Afghani journalism remained limited and mostly a vehicle for resonance with ruling thought.

By 2001 the two most influential dailies were Anis ("Companion" or "Friendship"), founded in 1927 with a circulation estimated at 25,000 and published in Dari but including articles written in Pashtu and Uzbek, and Hewad ("Homeland"), founded in 1959 with a circulation estimated at 12,000 and published in Pashtu. Both are based in Kabul and controlled by the Ministry of Information and Culture. These four-page "dailies" came out only several times a week, however, and reached only 11 per 1,000. Nevertheless, such a distribution rate represents a marginal increase from the 1982 rate of 4 per 1,000.

Other principal dailies, estimated at no more than 14, were headquartered in Kabul and in such provincial centers as Baghlan, Faizabad, Farah, Gardiz, Herat, Jalabad, Mazar-i-Sharif, Shiberghan, and Qandahar. These provincial papers mostly relied on the Kabul dailies for news, and averaged around 1,500 in circulation.

An independent Afghani press, then, has not existed in Afghanistan since 1973. The nearest relative to such an entity would be an Afghan-owned daily that began operations in Peshawar, Pakistan, in the late 1990s. With formal news channels so restricted and unidimensional, informal news networks have flourished in the bazaars of Kabul and other cities. A mixture of fact and fantasy, this news has circulated orally and through shahnamahs (night letters).

Economic Framework

Afghanistan has had a modern history of oppression, war, and poverty. A mountainous, landlocked country in southwest Asia, with dry climate and temperature extremes, its arable land is only around 12 percent. Nevertheless, almost 70 percent of its labor force is engaged in agrarian activity. In general, the population has a small per capita income (around U.S. $170) and a life expectancy that is the lowest in Asia (around 47 years-of-age).

The Hindu Kush Mountains separate the country into northeast and southwest sections, roughly speaking, a division that has impeded commercial and political relations between these areas. The Taliban, an Islamic fundamentalist militia, ruled approximately 80 percent of Afghanistan between 1996 and 2002. The Northern Alliance, their last remaining opponents with a stronghold in the northeast corner, laid claim to the remaining 20 percent.

Modern printing machines began operating in Afghanistan in 1927, although the printing standards remain behind the times. Much of the type continues to be set by hand.

Questions relevant to journalism in technologically advanced countries—competition, advertisers' influence, reporter power, and the like—simply are not relevant to Afghanistan. As a country entrenched in the beginning stages of progress, in fact, Afghanistan has substantial barriers to media development. These obstacles include inhospitable terrain, mixed ethnic groups with historic conflicts, language differences, low literacy and income levels, underdeveloped educational and other social welfare institutions, and a governmental structure dominated by religious intolerance.

Press Laws

The 1964 Constitution of Afghanistan and the Press Law of July 1965 provided for freedom of the press subject to comprehensive articles of proper behavior. According to the Press Law, the press was free (i.e., independent of government ownership) but must safeguard the interests of the state and constitutional monarchy, Islam, and public order. When the government was overthrown in July of 1973, 19 newspapers were shut down. Western-style freedom of the press has systematically eroded during the regimes of dictatorship, communism, Mujahidin factions, and the Taliban.

Censorship

By 2002 it appeared that traditional forms of press freedom were simply nonexistent in Afghanistan. Because the ruling movement strictly interpreted Muslim Sharia law and banned representation of people and animals, for example, newspapers were picture-free— censorship in which Afghanistan stands alone in the world. Had newspapers been allowed to print photographs, women would have appeared only in full veil and men in full beard. This suppression of freedom of expression extended to a complete ban on music and films.

Self-censorship also has been a problem because of the threats received by journalists after writing articles critical of the Taliban. Afghan journalists, working both locally and in exile, have been subject to warnings as well as fatwas (death threats) for writing unpopular reports. These threats have sometimes materialized into murder.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

The Taliban enforced heavy restrictions on foreign journalists who were provided with a list of 21 rules. The principal positive rule required journalists to give a "faithful" account of Afghani life. The succeeding rules represented a series of restrictions, the umbrella of which was a prohibition on journalists traveling unaccompanied by Taliban "minders." These watchdogs were there to ensure that journalists abided by the limitations, which included bans on entering private houses, interviewing women, and the like.

Foreign journalists, as well as Afghani journalists, often have been harassed. A number of examples exist of reporters who have been wounded, kidnapped, or murdered—grim reminders of the dangers journalists face while trying to perform their job in an unstable country.

The only foreign broadcaster permitted entry to Afghanistan has been Al Jazeera, an independent satellite television station home-based in Qatar and seemingly owned, at least indirectly, by the Qatari government. Although the channel may not always promote "Arab brotherhood," as defined by the Arab States Broadcasting Union's code of honor, it also has been willing to air anti-American views and statements by Osama bin Laden, even after the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001. Labeled a maverick, and regarded as the most popular television channel in the Arab culture, Al Jazeera may come closest to uncensored programming among Arab media.

News Agencies

The Bakhtar News Agency, responsible for domestic news collation and distribution to all domestic media, reports to the Ministry of Information and Culture. Leaders in both these units traditionally have been appointed based on their loyalty to the ruling government.

Two Pakistani-based news agencies have been launched by Afghani refugees—the Afghan Islamic Press and the Sahaar News Agency. They manage to produce bulletins with varying degrees of accuracy for mostly Western wire services.

Because of the dangers to journalists based in Afghanistan, foreign news bureaus have shrunk. By 2001 only three countries were represented by news agencies in Kabul: Czechoslovakia, Russia, and Yugoslavia.

Broadcast Media

Color television broadcasting began in 1978. The Taliban banned television and closed the station in 1996. Taliban religious police smashed privately owned television sets and strung up videocassettes in trees in a form of symbolic execution by hanging. Anyone found harboring a television set was subject to punishments of flogging and a six-month incarceration.

In the northeast, however, Badakhshan Television broadcast news and old movies for three hours every evening. Financed by the Northern Alliance, the station's audience was limited to around 5,000 viewers (among 100,000 residents in Faizabad without electricity) who could muster some kind of home-generation power source. Although a marginally effective news channel, it became a symbol of light in a more freely communicating society in direct opposition to the darkness imposed by the Taliban.

Radio is the broadcast medium of choice in Afghanistan, an option well suited to a low-literate society, although most people do not have a radio (radio ownership is around 74 per 1,000). The Radio Voice of Sharia (Islamic law), founded in 1927 as Radio Kabul and controlled by the Ministry of Information and Culture, was programmed by the Taliban to provide domestic service up to 10 hours daily in Dari and Pashtu; daily domestic service of 50 minutes in Nurestani, Pashai, Turkmen, and Uzbek; and 30 minutes of foreign service in English and Urdu. Broadcast topics were mainly of religious orientation, unrelieved by music.

Summary

The history of mass media in Afghanistan, especially recent history, is dominated by such adjectives as restricted, censored, under-developed, and nonexistent. Its future undoubtedly relies on the establishment of peace, prosperity, and a philosophy of communication that promotes civil government. Because country development and modern communications technology are correlated, Afghans would do well to create a society that offers freedom of information and human respect, regardless of demographic label, to all.

Significant Dates

- 1996: Taliban capture Kabul and Jalalabad, effectively assuming control of Afghanistan. Ban television. Impose heavy restrictions on radio and print media.

- 2001: Terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and on the Pentagon in the United States. Al Qaeda, a terrorist organization headquartered in Afghanistan, held responsible. United States responds with air and ground strikes aimed at destroying the Taliban, who refuse to surrender Al Qaeda.

- 2002: Taliban overwhelmed. A measure of freedom returns to Afghanistan as freer press, music, and television begin a resurgence.

Bibliography

Abu-Fadil, Magda. "Maverick Arab Satellite TV: Qatar's Al-Jazeera Brings a Provocative New Brand of Journalism to the Middle East." IPI Report 5, no. 4 (1999): 8-9.

"Afghanistan." The Europa World Yearbook 2001, 365-385. London: Europa Publications, 2001.

"Afghanistan: Media Chronology Post-11 September 2001." BBC Monitoring International Reports, 16 January 2002. Available from http://www.lexis-nexis.com .

"Afghanistan." The World Fact Book 2000, 1-3. Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency, 2000.

"Afghanistan." World Press Freedom Review 2000, 110-111. Columbia, MO: International Press Institute, 2000.

Farivar, Masood. "Dateline Afghanistan: Journalism under the Taliban." CPJ Briefings: Press Freedom Reports from around the World, 15 December 1999. Available from http://www.cpj.org .

Goodson, Larry. Afghanistan's Endless War. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2001.

Kaplan, Robert D. Warrior Politics: Why Leadership Demands a Pagan Ethos. New York: Random House, 2002.

Lacayo, Richard. "The Women of Afghanistan: A Taste of Freedom." Time 158, no. 24 (2001): 34-49.

Lent, John A. "To and from the Grave: Press Freedom in South Asia." Gazette 33, no. 1 (1984): 17-36.

Marsden, Peter. The Taliban: War and Religion in Afghanistan. London and New York: Zed Books, 2002.

Rashid, Ahmed. "Heart of Darkness." Far Eastern Economic Review 162, no. 31 (1999), 8-12.

——. "The Last TV Station." Far Eastern Economic Review 162, no. 38 (1999), 38.

Razi, Mohammad H. "Afghanistan." Mass Media in the Middle East: A Comprehensive Handbook, eds. Yahya R. Kamalipour and Hamid Mowlana, 1-12. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1994.

The World Almanac and Book of Facts 2001. New York: World Almanac, 2001.

World Association for Christian Communication. U.S. Pressures Al-Jazeera, November 2001. Available from http://www.wacc.org.uk .

Clay Warren

The second one was Sarajul Akhbar and it was that was published in 1906, so it is not eight years before Afghans Gained their independence from Great Britain, but it was 13 years before...

Further comments will be fallowed later

Thanks

The first Afghani published newspaper was Shamsul Nehar that was published in 1873 and the second one was Sarajul Akhbar and it was published in 1906, so it seems that it is not published eight years before Afghans Gained their independence in 1919, but it was published 13 years before...

Further comments will be fallowed later.

Thnaks

Thanks

Further comments will be followed!

Further comments will follow later.

Thanks