Albania

Basic Data

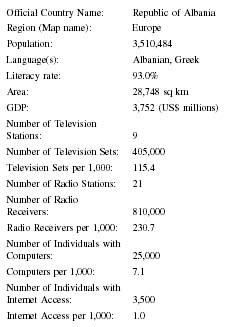

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Albania |

| Region (Map name): | Europe |

| Population: | 3,510,484 |

| Language(s): | Albanian, Greek |

| Literacy rate: | 93.0% |

| Area: | 28,748 sq km |

| GDP: | 3,752 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Television Stations: | 9 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 405,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 115.4 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 21 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 810,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 230.7 |

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 25,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 7.1 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 3,500 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 1.0 |

Background & General Characteristics

Albania is a land of clans. For centuries the clans of Albania have feuded with each other, making this eastern Adriatic region susceptible to occupation by stronger empires. For two decades in the fifteenth century the clans of Albania united in an alliance against the Ottoman Turks under the leadership of Gjergj Kastrioti (1403-1468), better known as Iskander Skanderberg. The Turkish surrender to Skanderberg in 1444 brought Albania a brief period of decentralized national unity. Skanderberg's death in 1468 from wounds at the battle of Lezhe against the Ottoman Turks returned Roman Catholic Albania to the Muslim control of Constantinople. A red flag with Skanderberg's heraldic emblem remained the symbol of Albanian independence under five centuries of Ottoman occupation.

In the nineteenth century Albanian intellectuals standardized the Albanian language, a unique mixture of Latin, Greek, and Slavic dialects, creating a literary style for educational use. The Society for the Printing of Albanian Writings, founded by Sami Frasheri in 1879, sought national reconciliation from Muslim, Catholic, and Eastern Orthodox Albanians and the use of the Albanian language in the region's schools. For most of Albania's history, education in Muslim-controlled Albania was under the jurisdiction of the Ottomans and their surrogates, the Greeks, who banned Albanian language-based education and required Albanians to be educated in Turkish or Greek. Albanian exiles in Romania, Bulgaria, Egypt, Italy, and the United States kept the Albanian language alive by writing and printing textbooks and smuggling them into their homeland.

The gradual economic and political disintegration of the Ottoman Empire in the late nineteenth century and the empire's military defeats in the twentieth century against successful nationalistic waves of independence by Serbians, Romanians, Greeks, Montenegrins, and Bulgarians provided the Albanian people with the opportunity to seek their own independence. Albanian guerrilla movements within Albania worked with Albanian supporters of the Young Turk movement throughout the Ottoman Empire to destabilize it. Albanian efforts brought fleeting rewards. In 1908 the Ottoman government restored the Albanian language as the educational language for instruction and offered some local political autonomy; however, a new Turkish government in 1909 immediately reversed its position on Albania. Albanian resistance ultimately was successful when Ottoman overlords granted Albania local autonomy in 1911, extending to Albanians local control over the educational system, military recruitment, taxation, and the right to use the Latin script for the Albanian language.

A series of Balkan wars in 1912 and 1913 by Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece, and Montenegro against the Ottoman Empire offered Albania the opportunity to declare its own independence in the city of Vlores in November 1912. The London Conference of 1913 on the Balkans ultimately granted Albania full independence from the Ottoman Empire under the protection of Europe's Great Powers (Russia, Great Britain, France, Austria, and Germany). As would be true for most of the twentieth century, Albania's future was shaped by other nations, not by the Albanian people. The Great Powers acceded to the demands of Serbia and Montenegro for Albanian districts. Albanians living in Kosovo and western Macedonia were placed under the jurisdiction of Serbia, not Albania.

An independent Albania was constituted as a constitutional monarchy ruled by an imported German prince, Wilhelm zu Wied, who was unprepared for the realities of Albanian politics. Prince Wilhelm barely controlled the major cities of Durres and Vlores. He left his country after a brief six months. World War I brought deals from the Allies in exchange for support from Albania's neighbors. Italy, Montenegro, and Serbia were each promised Albanian land in return for military assistance against the German and Austrian armies. Albania's future was again determined by other nations unwilling to allow all Albanians to be part of a "Greater Albania."

U.S. diplomatic intervention kept Albania independent after World War I. The newly formed Kingdom of Yugoslavia (Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes) backed Albanian chieftain Ahmed Bey Zogu, believing him a pliable tool for Belgrade's interests in the acquisition of additional Albanian territory. Zogu first established his control within Albania and then turned on his Yugoslav benefactors by making himself President of Albania in 1924 and King in 1928. King Zog turned to Italy for international support against Yugoslavia. Over the next 15 years, Albania came under greater Italian control. Roman Catholic schools were established to replace Muslim ones and Italian became the language of education. Zog's regime was both repressive and censorious. In 1939 King Zog was overthrown by the Italian military. He fled into permanent exile leaving Albania under the control of Rome until Italy's defeat and surrender in 1944.

King Zog and his ministers were never accorded Allied recognition as a government-in-exile. The only major internal resistance in Albania against Italian and German troops was a communist insurgency led by Enver Hoxha. British support provided the critical leverage creating a People's Republic of Albania in 1944. During the next five years all opposition to Hoxha's communist government was eradicated. The media was seized by communist authorities in 1944 but not nationalized until 1946. All media forms were used to instill Marxist values and justify communist rule. Albanian writers and artists were commissioned to rewrite Albania's past to depict a population both backward and besieged, thankful for the advances a communist regime could offer. The press, radio, and television urged implementation of communist economic programs and supported antireligious campaigns and literacy promotion. The media was instructed to appeal to Albanian nationalism to force the public's acceptance of the communist dictatorship's agenda. All newspapers were under the control of the communist government and printed only what they were told. Albania's few radio and television stations spoke only the communist credo. All journalists, editors, film directors, and television and radio producers were either communist party members or severely subjected to the discipline and guidelines of the party. For the next four decades Albania under President and Communist Party leader Enver Hoxha brutally suppressed all dissent, denied the Albanian people human rights, and isolated Albania from all European countries with only distant China, little Albania's primary ally. The communist party published the nation's most important newspaper, Zeri I Popullit (Voice of the People).

A 1984-study commissioned by Amnesty International identified Hoxha's Albania as one of the world's most repressive regimes. Albanians were denied the freedoms of expression, religion, movement, and association in contradiction to the country's 1976 constitution, which stated the nation's political liberties. The only information available to the Albanian people came from the government-controlled media. Hoxha's death in 1985 led to minor improvements in the communist rule of Albania under Hoxha successor, Ramiz Alia. Alia loosened some of the nation's harshest restrictions on human rights and the media. Internal dissent and mounting demonstrations in Albania led Alia to sign the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, which guaranteed Albanians both human and political rights as part of the Helsinki accords of 1975. After press laws were liberalized in 1990, Zeri I Popullit rapidly lost circulation. Opposition papers were printed; the most popular newspaper became Rilindja Demokratike. To regain subscribers Zeri I Popullit removed the hammer and sickle and the Marxist slogan from its masthead and relinquished its role as the mouthpiece of the Communist Party.

In 1990 Albania reorganized itself into a multiparty democracy. Student unrest in 1990 led to violent clashes. The political party, the Democratic Front and its daily newspaper, Bashkimi, covered the clashes, arrests, and police activity. This was Albania's first public criticism in the media since the 1944 communist takeover. Albania's government acted with a new sense of responsibility, and the Council of Ministers proceeded to liberalize the laws regulating the media, reduced the Communist Party's control of the press, and legalized the nation's first privately owned opposition newspaper, Rilindja Demokratike.

Albania adopted a new constitution in 1998 to bring the nation into full compliance with the constitutions of Europe's other nations and to facilitate Albania's need for foreign investment in the nation's financial future. Under the 1998 constitution the nation's head of state is a president elected for a five-year term by the legislature. The president, who is advised by a cabinet, appoints the prime minister. Albania has a unicameral legislature ( Kuvendi Popullor ) with 155 members serving four-year terms. Most legislators are elected by direct popular vote with a smaller number elected by proportional vote. Part Two of the constitution, The Fundamental Human Rights and Freedoms, guarantees the Albanian people human rights and freedoms that are indivisible, inalienable, and inviolable, and protected by the judicial order. Article 22 provides for freedom of expression, and freedom of the press, radio, and television. Prior censorship of a means of communication is prohibited. The operation of radio and television stations may require the granting of a government authorization. Article 23 guarantees the right to information. All Albanians have the right, in compliance with the law, to get information about the activities of the government and about the individuals exercising governmental authority.

In 1996 Albania published five national dailies with a combined circulation of 116,000. In 1995 the four largest newspapers were the Albanian language morning dailies Zeri I Popullit, 35,000 circulation; Koha Jone, 30,000 circulation; Rilindja Demokratike, 10,000 circulation; and the Albanian and Italian language morning daily Gazeta Shqiptare, 11,000 circulation. Dy Drina is published in northern Albania and has a circulation of 1,000. According to 1995 statistics, general-interest biweekly periodicals circulated as follows: Alternativa, published by the Social Democratic Party, 5,000 readers; Bashkimi, published by the Democratic Front, 5,000 readers; and Republika, published by the Republican Party, 8,000 readers. Weekly general interest periodicals are Ax, 6,000 readers; Drita, 4,000 readers; and Zeri I Rinise, a Youth Confederation publication, 4,000 readers. Lajmi I Dites, published by the ATS News Agency, has three issues per week and a circulation of 5,000. Special interest publications are the monthlies Albanian Economic Tribune in both Albanian and English with 5,000 readers; Arber, published by the Ministry of Culture with 5,000 readers, and Bujqesia Shqiptare, published by the Ministry of Agriculture with 3,000 readers. Weekly special interest periodicals are Mesuesi, published by the Ministry of Education, 3,000 circulation, and Sindikalisti, circulation 5,000. The University of Triana publishes the biweekly Studenti, with a circulation of 5,000, and the quarterly Gruaja Dhe Koha has 1,000 readers. The quarterly Media Shqiptare, founded in 1999, caters to journalists and provides news about the profession.

The Albanian print media is generally characterized as an extension of political parties. It is perceived as more opinion than factually based. Albanian newspapers have distribution problems. They are sold in the cities, which omit 60 percent of the population residing in the countryside. Newspapers lack adequate revenue to cover printing costs and salaries for a professional staff. Since 1999 newspaper circulation has dropped from 75,000 to 50,000 readers. A majority of Albanians believe that the print media are a negative national influence. Polls indicate that Albanians prefer to receive their news via electronic means.

Albania has had one government owned radio station, Radiotelevizioni Shqiptar. The nation's previously government-owned television station is also called Radiotelevizioni Shqiptar. In 1999, both stations were merged into a public entity no longer financed by the state and without direct linkage to the government. Radiotelevizioni Shqiptar (RTSH; Albanian Radio Television) is under the jurisdiction of the National Council for Radio and Television and regulated by a committee whose members are chosen by Albania's parliament.

Economic Framework

The population of Albania is 95 percent Albanian. The remaining 5 percent of the Albanian population is Greek (3 percent) and Vlachs, Gypsies, Serbs, and Bulgarians (2 percent). Albania is overwhelmingly Muslim (70 percent). Albanian Orthodox Christians represent 20 percent of the population, and 10 percent of Albanians are Roman Catholic.

Albania is one of Europe's poorest nations. The transition from a communist, highly centralized economy to a privatized capitalistic system has had serious repercussions for Albanians. Albania suffered a severe economic depression in 1990 and 1991. The economy improved from 1993 to 1995, but political instability led to increasing inflation and large budget deficits, 12 percent of the gross national product. In 1997, the Albanian economy collapsed under pressures from a financial pyramid scheme to which a large segment of the population had contributed. Severe social unrest led to over 1,500 deaths, the destruction of property, and a falling gross national product. A strong government response curbed violent crime and revived the economy, trade, and commerce. Albanian workers overseas, primarily in Greece and Italy, represent over 20 percent of the Albanian labor force. They contribute to the nation's economic well being by sending money back to their families in Albania. In 1992, most of Albania's farmland was privatized, which increased farming incomes. International aid helped Albania pay for ethnic Albanians from war-torn Kosovo living in refugee camps in Albania. Albania's work force is divided among agriculture (55 percent), industry (24 percent), and service industry (21 percent). The nation's major industries are food processing, textiles and clothing, lumber, oil, cement, chemicals, mining, basic metals, and hydropower.

Due to international pressure, under the leadership of Ramiz Alia Albania relaxed political and human rights controls. National amnesties in 1986 and 1989 released political prisoners held for years. By 1990, Alia supported a more open press and freedom of speech. The press covered controversial topics, sometimes resorting to sensationalism to increase circulation.

Albania is poorly represented in the telecommunications field with an obsolete wire system. Telephone wires were cut in 1992 by villagers and used to build fences. There is no longer a single telephone for each Albanian village. It is estimated that there are two telephones for every 100 Albanians. The lack of a telecommunications network is being alleviated by Vodafone Albania, a subsidiary of Vodafone Group Plc. Vodafone competes with Albania Mobile Communications (AMC) for the sale of cell phones in a nation without regular telephone communications. State run Albtelecom was privatized in 2002. Albtelecom has two Internet Service Provider licenses supporting ISDN and NT connections in five major Albanian cities and plans to expand and serve the university population. The competition of all three companies will allow Albania to catch up in the telecommunications industry on a level compatible with the European Union nations.

International communication is frequently carried by microwave radio relay from Tirana to either Greece or Italy. During the communist era radio and television were exclusively used for propaganda purposes. In 1992 the government owned and operated all 17 AM radio stations and the sole FM station, which broadcast two national programs as well as regional and local programs throughout the country. Popular Albanian broadcast frequencies are AM 16 and FM 3. There are two short-wave frequencies. Albania has nine television stations. Programming is broadcast in eight languages and reaches Albanians in Africa, the Middle East, North and South America, and Europe. Until the early 2000s all radio and television stations were broadcast exclusively over government-controlled frequencies and were usually propaganda based. This has changed significantly with the restructuring of the RTSH.

Press Laws & CENSORSHIP

Albania's rapid transition from an isolationist communist state to western-style democracy was fraught with difficulties. The 1999 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices reported that the nation's security forces usually respected Albania's Law on Fundamental Human Rights and Freedoms, but there were incidents in 1999 where journalists were beaten. The report noted that the media were given the freedom to express views, but the press seldom used self-restraint in what it printed. News stories were given to sensationalism and lacked professional integrity, contained unsubstantiated accusations, and sometimes included complete fabrications. In 1999 Albania's political parties, labor unions, and professional and fraternal groups and organizations published their own newspapers and magazines. In that year, there were at least 200 such publications available on a daily or weekly basis. Newspaper sales were falling because the public lacked trust in what was being reported. In 1999 new privately owned radio and television stations began to emerge to compete with the print media for circulation. At least 50 television and 30 radio stations competed with the RTSH, formerly run by the state. To control a proliferation of broadcast media stations, the government approved new licensing requirements. The National Council of Radio and Television was created to regulate the licensing of radio and television stations. The Council's membership is equally divided between the government and the opposition political parties.

The 2001 World Press Freedom Review noted that the Albanian press showed increased maturity and professionalism in reporting the news. Professional standards for the hiring of journalists reflected a significant improvement. In 2001, the media's professionalism was increasingly evident in their reporting on the conflict in neighboring Macedonia with its large ethnic Albanian population and Albania's general elections of June 2001. A lack of financial resources forced the Albanian media to increasingly depend on foreign news sources for international coverage. Journalists' bias and opinion are now more likely to appear in newspaper editorial pages than in the newspapers front-page articles. The World Press Freedom Review criticized the media for a lack of critical analysis about political candidates running for public office and the failure to cover some important national events. Press coverage on the Socialist Party (the former Albanian Communist Party) was criticized in the report for being overly critical and biased. The broadcast media were noted as providing more balanced coverage. Only the public television channel TVSH was sited for biased reporting with 40 percent of the coverage focused on the Socialist Party and 11 percent of the coverage for all the other opposition parties. As a result the National Council for Radio and Television fined TVHS for bias in reporting for the Socialist Party.

In 2001, Albania's government debated a new media law, Article 19 for Freedom of the Press, to regulate the media. Opposition lawmakers feared Article 19 might compromise press freedom by making journalists responsible for what was printed regardless of who authorized the article. Article 19 also required all journalists to register with a Journalists' Registry and to be experienced before being licensed by the state, and made publishers legally liable for hiring unlicensed journalists. Article 19 required journalists to report only truthful and carefully checked news stories. False news articles would be considered a criminal offense. A national debate concluded that Article 19 was likely to be in contradiction to European Union media practices, which required the media to police and discipline itself.

News Agencies

For the majority of its media history, Albania has had only one principal news agency, Agjensia Telegrafike Shqiptare. There are three media associations, the Journalists Union, the Professional Journalists Association, and the Writers and Artists League. E.N.T.E.R. is the first Independent Albanian News Agency. Founded in 1997 by a recognized group of well-known independent journalists, E.N.T.E.R. negotiates contracts for the sale and distribution of news with independent newspapers, private radio stations, state radio and television stations, state institutions, and international organizations. E.N.T.E.R. is divided into three departments, Interior News, Foreign, and Technical, with correspondents in Albania's 12 administrative districts. Tirfax offers information in English but not a single Albanian newspaper uses it.

Broadcast Media

The National Council for Radio-Television regulates broadcasting. The president appoints one member, and the Commission on the Media, which is made up of representatives selected equally by the government and the opposition parties, chooses six members. The National Council broadcasts a national radio program and a second radio program from 14 stations. Statistics for 1997 indicated that Albanians owned 810,000 radios and 405,000 television sets. The electronic media law of September 30, 1998 provides for the transfer of the state-owned RTSH to public ownership under the authority of the National Broadcasting Council. An amended state secrets law, passed in 1999, eliminated references to punishing media institutions and journalists for publishing classified information. Penal code punishments have not been dropped.

In 2000, many Albanian television stations operated illegally without government licenses. There were 120 applications with 20 television stations competing for two national channels. The National Council for Radio and Television granted the two national channels to TV Klan and TV Arberia. TV Shijak, one of the television losers, criticized the decision as being politically motivated. Other television stations were granted licenses for local broadcasting including TV Teuta. Most television and radio stations are joint ventures with Italian companies. Despite the criticism, Albanian media is increasing in number and reflecting the political and economic stability of the nation. RTSH tends to provide more government information as it makes the transition to a private network system. It is the only station to broadcast throughout the entire country.

Radio Koha, Radio Kontakt, Radio Stinet, Radio Top Albania, and Radio Ime are Albanian's most popular radio stations. Their programming emphasizes music, news, and call-in shows. Albanians receive FM broadcasts from the Voice of America, British Broadcasting Corporation, and Deutsche Welle on short wave.

Electronic News Media

Electronic media in Albania is a relatively recent addition to the media. The list of electronic media is growing at a rapid rate. AlbaNews is a mailing list dedicated to the distribution of new and information about Albania, Kosovo, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Montenegro, and Albanian living around the world. Major contributors to AlbaNews are Kosova Information Center, OMRI, Albanian Telegraphic Agency, Council for the Defense of Human rights and Freedoms in Kosova, and Albanian Weekly (Prishtina). Electronic Media newsgroups for Albania include soc.culture.albanian, bit.listserv.albanian, clari.news.Europe.Balkans, alt. news.macdeonia, soc.cuture.yugoslavia, and soc. culture.europe.

The Albanian press with Internet Web sites are Koha Jone, Gazeta Shqiptare, Gazeta Shekulli, Gazeta Korrieri, Sporti Shqiptar, Zeri I Popullit, Republicka, Revista Klan, and Revista Spekter. Internet sites are available for a number of Albanian print media, which includes the Albanian Daily News, AlbaNews, Albania On-Line, ARTA News Agency, Albanian Telegraphic Agency, BBC World Service Albanian, Dardania Lajme, Deutsche Weel-Shqip, Kosova Crisis Center, Council for the Defence of Human Rights and Freedoms, Kosova Press, Kosova Sot, and the Kosova Information Center. Albanian periodicals with Internet sites are Blic, Fokus, International Journal of Albanian Studies, International War and Peace Report, Klan, and Pasqyra.

Albanian radio stations with online sites are Radio 21, Radio France Internationale, Lajme ne Shqip, and Rilindja. Albanian television stations with Internet sites are Radio Television of Prishtina Satellite Program, Shekuli, TV Art, TVSH-Programi Satelitor, and the Voice of America Albanian Service.

Albaniannews.com was the nation's first electronic media to go online in 1991 as a private company. The company's Independent Albanian Economic Tribune, Ltd. was Albania's first economic online monthly. In 1995, the English-language Albanian Daily News was offered

Education & TRAINING

The only institution of higher learning in Albania to offer degrees in media related careers is the University of Tirana. Founded in 1957, the University of Tirana is a comprehensive university with seven colleges and 14,320 students. The faculty of History and Philology, a college that also includes history, geography, Albanian Linguistics, and Albanian Literature, offers a degree in journalism. The University of Tirana's increasing cooperation with European Union institutions offers Albanian students the opportunity to transfer to universities outside Albania for programs of study in the media not offered there.

Summary

Albania is a nation beset with a multitude of problems generated by centuries of isolation and control during the rule of the Ottoman sultans and the interventionism by Yugoslavia, Italy, and the Soviet Union in Albania's internal affairs. World War II and the ultimate victory of communist insurgents led to four decades of xenophobic control and the isolationism of Albania from the rest of Europe. The development of a democratic system has resurrected internal feuding among newly organized political parties that occasionally reflect Albanian clans likely to renew historic feuds. Ethnic Albanians living in the Serbian province of Kosovo and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia involve the Republic of Albania in the politics of its neighbors.

Significant Dates

- 1985: Death of Enver Hoxha, Communist leader of Albania since 1944.

- 1990: Albania begins the transition to a multiparty democracy.

- 1997: Pyramid financial investment scheme collapses causing an economic crisis.

- 1998: Approval of a new constitution.

Bibliography

1999 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, Albania. Washington, DC: United States Department of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, 2000.

2001 World Press Freedom Review. Available from www.freemedia.at/wpfr/albania.htm .

Glenny, Misha. The Balkans, Nationalism, War and the Great Powers, 1904-1999. New York: Viking Press, 2000.

International Journalists' Network. Available from www.ijnet.org .

Kaplan, Robert. Balkan Ghosts. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1993.

Turner, Barry, ed. Statesman's Yearbook 2002. New York: Palgrave Press, 2001.

World Mass Media Handbook. New York: United Nations Department of Public Information, 1995.

Zickel, Raymond, and Walter R. Iwaskiw, eds. Albania: A Country Study. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1994.

William A. Paquette , Ph.D.

In albania is spoken only one lenguage: Albanian

This is the truth and everybody knows that.