Algeria

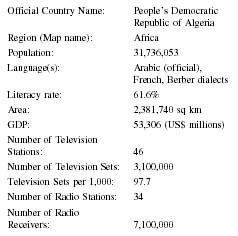

Basic Data

| Official Country Name: | People's Democratic Republic of Algeria |

| Region (Map name): | Africa |

| Population: | 31,736,053 |

| Language(s): | Arabic (official), French, Berber dialects |

| Literacy rate: | 61.6% |

| Area: | 2,381,740 sq km |

| GDP: | 53,306 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Television Stations: | 46 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 3,100,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 97.7 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 34 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 7,100,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 223.7 |

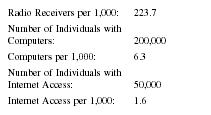

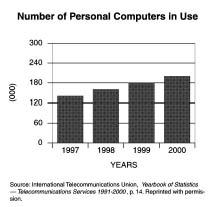

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 200,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 6.3 |

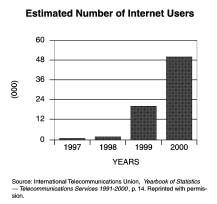

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 50,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 1.6 |

Background & General Characteristics

The development of the Algerian press can be categorized into five periods: 1962-65, when the editors of newspapers were intellectuals of the FLN (National Front of Liberation) who enjoyed a certain autonomy; 1965 to 1988, a period when the intellectuals were replaced by civil servants who were docile instruments of the state bureaucracy; 1988 to 1992, when the press enjoyed greater freedom and several new papers appeared; 1992 to 2000, when journalists were restricted and threatened; and the period after 2000, when journalism had regained some of the freedom lost during the early 1990s.

Since the 1960s, when Algeria became independent from France, the press has been controlled by the ruling party, the FLN . Three years into the nation's independence, freedom of press became unknown to journalists and newspapers. Before the late 1980s, Algeria was home to three main government-run newspapers, El-Moudjahid (The Freedom Fighter) in French, Ech-Chaab (The People) in Arabic, and the weekly Algérie Actulalité in French. In the nineties, readership of these newspapers declined and Algérie Actualité was discontinued. Numerous privately owned newspapers have been created since.

In 1988, popular pressure brought about the explosion of the Algerian political system and the liberalization of the press. About two years later, new legislative elections were on the verge of placing the Islamists in power when the army, under the pretext of saving a young democracy, cancelled the elections and seized power. Over 100,000 Algerians were victims of the civil war that followed. Journalists and intellectuals were assassinated by armed Islamist groups and by the military in power.

According to the Algerian government, mass media should be under complete government control. Capitalist inclinations and individualism have been discouraged. Algeria has followed the populist socialist path. Capitalism is rejected, and instead, focus is placed on the public sector. Before the events of October 1988, it was impossible for journalists to investigate or publish material relating to government activities, unless the government furnished said information. Radio and television were government-run and censored, and the print media was published either by the government or the FLN (the party that ruled Algeria for 30 years.) The authorities also tightly controlled the circulation of foreign journals.

The military-backed regime that came to power in January 1992 curtailed the press and restricted freedom of expression and movement. In the 1990s, a number of newspapers were shut down, journalists were jailed and some disappeared, while others were openly assassinated. In some of the murder and disappearance cases, both the Islamists and the government have attracted suspicion.

In 1990, a ministerial decision guaranteed two years of salary to journalists in the public sector that created or worked for new independent or partisan newspapers. As a result, a virtual stampede of journalists and editors founded new publications. Like new political parties, new newspapers appeared. However, in 2000, it was reported that state controlled printers delayed the publication of certain newspapers for political reasons. Some newspapers accused the state of favoritism when it came to distributing government advertising.

One hundred journalists and other media workers have been murdered from May 1993 to August 1997. While Islamists were blamed for most of the killings, the Algerian government was believed to have played a role in some of the killings. The fate of many other journalists is unknown as of 2002.

Circulation

In 1993, there were 117 publications: 21 dailies, 34 weeklies and 62 periodicals, 57 of which were printed in the Arabic language and 60 in the French language. In 1996, the number of publications went down to 81: 19 dailies, 44 weeklies and 10 magazines. The total number of journalists was 1,700. Most of the big political parties used to have their own newspapers; however, due to financial constraints, the majority were discontinued. Nevertheless, among the remaining newspapers, many tend to take positions with different political parties. Dailies and weeklies such as La Tribune , L'Autentique ElSabah (the morning), El Djadid (the new), El Houria (the freedom), Le Quotidian d'Oran were created after 1992.

Amongst the most read French newspapers are El Watan , Le MatinLe Soir d'AlgérieLe Quotidiend'Oran, LibertéLa TribunL'AuthentiqueHorizons and the newly created L'Epression . El Watan is known for being unbiased. Le Matin and Le Soir d'Algérie are anti-government. Le Quotidien d'Oran is known for the high quality of its journalists. As for the latest addition, L'Expression , its editorials tend to defend the government and justify its actions.

The most respected Arabic newspapers are: El Khaber (The News) and El Youm (today.) Older newspapers, such as El Moudjahid and Ech Chaab , have lost grounds to more independent publications.

The media's effort to spread information to the different socio-economic classes has, for the most part, been unsuccessful. The educated and affluent elite that controls the content and dissemination of mass media to the whole of Algerian society often fails to reach classes outside of itself. Many rural Algerians are illiterate and too poor to own a television or buy newspapers. Those who do have access may not understand the Standard Arabic and French used in all forms of the media.

The present circulation the El-Moudjahid is about 40,000 for the entire country while El-Watan prints about 100,000 daily. The annual circulation of the Algerian newspapers is estimated at 364 million. Due to the high illiteracy rate in Algeria (41 percent in 1990), especially among the older generation, readership is confined to the elite.

Most of the Algerian urban population lives in the northern 10 percent part of the country. The southern part, the Sahara, is sparsely populated. Consequently, most publishing and other media activities are concentrated in the northern part of Algeria.

Economic Framework

The government officially announced in 1998 that a budget of 400 million Algerian dinars (about $6.5 million) had been allocated to aid the press. By 2001, 500 million Algerian dinars had been committed to aid journalists who opted to leave the public sector in favor of the private sector. This aid came in the form of two years of guaranteed salary.

From the establishment of a private press in 1990 until Dec. 31, 1995, the state subsidized the publishing costs by paying the difference between the actual cost and what the newspapers were able to pay. The state has also made available three press centers to public and private newspapers.

Press Laws

The Information Act, Law No. 90-7 (dated April 3,1990) regarding information forbids newspapers to publish any stories or information about political violence and security from any source other than the government. Algerian legislation prohibits criticism of the regime system as it is considered a crime affecting the state's security.

In 1999, an attempt to pass a law to end government monopoly over advertisement failed. During the same year, the government ended its monopoly over the Internet and opened the market to private Internet Service Providers.

Algerian journalists have the right to keep their sources of information and news confidential, a right considered one of the most prominent aspects of freedom of expression. This protects the journalists' resources against retribution and guarantees the flow of information.

Censorship

Algeria imposes through legislation a clear prior censorship on the content of media. The import of foreign periodicals through Algeria should be through a prior license issued by the concerned department after consultation with a higher council. The import by foreign corporations and diplomatic missions of periodical publications meant for free distribution is possible after obtaining a license from the concerned department.

Before the 1988 riots, it was impossible for journalists to investigate or publish material relating to high-level government corruption, unless the government provided said information. The print media was published either by the government or the FLN .

Nevertheless, during the last few years of the second millennium and the beginning of the third millennium, the Algerian press offered a wide range of news, events, comments and stories that were previously taboo such as AIDS, prostitution and corruption.

Additionally, two democratic and independent organizations, the Association of Algerian Journalists (AJA) and the National Union of Algerian Journalists (SNJA), were formed during the state of emergency that was in place after the 1988 riots. In the late nineties, the SNJA organized large demonstrations demanding the return of suspended newspapers.

State-Press Relations

The government controls the supply of newsprint and owns the printing presses and is therefore able to put economic pressure on the newspapers. The state also exercises authority over the distribution of advertising, giving preferential treatment to the newspapers whose content is in line with the views of the government. President Bouteflika has stated that the media should "ultimately be at the service of the state."

Harassment of the privately owned press, whether legal, economic or administrative, was common practice. In mid-October, 1998, the state-run printing presses decided to stop printing the two most read newspapers, the dailies El Watan and Le Matin after they were given a 48-hour ultimatum to pay their debts in full. This came despite the April agreement to pay any debts in installments until December 31, 1998. The suspension decision came after El Watan and Le Matin published a series of articles and letters directing accusations against the Minister of Justice and a close advisor of the President of the Republic. Subsequently, both officials were forced to resign. The public (and the journalists) saw the suspension of the newspapers as a punishment for exposing government officials. Four newspapers owned by a former advisor to the president were also in debt, but continued to print.

In solidarity with the two suspended newspapers, many other newspapers voluntarily stopped the printing of their publications. This incident gave more credibility to the privately-owned press; subsequently, Algerians realized the importance of independent newspapers.

During the period 1993-98, journalists and media workers were targeted by the various extremist Islamic terrorist groups. As a result, 60 journalists and 10 media workers were assassinated, while five journalists were reported missing. Both the extreme Islamic groups and the government were suspected to have participated in their disappearance.

For security reasons, about 600 journalists have been housed in hotels and other housing units in proximity of Algiers under the protection of security guards. The government assumes full responsibility of the incurred costs.

When the journalists are spared death, they are faced with imprisonment, fines or suspension of their newspapers if they do not comply with state law. As the state continues to exert leverage over private newspapers through its ownership of the country's main printing houses, it also possesses the power to summon journalists to court.

Attitude Toward Foreign Media

Foreign correspondents have restricted access to Algerian affairs. Foreign media have accused the Algerian government of implementing a restrictive policy toward the granting of entry visas to foreign journalists. However, government-released figures show that in 1998, 626 foreign journalists were allowed to enter the country. These foreign journalists, mostly European, have reported limited access to opposition figures and to local sources who are willing to discuss political violence and other sensitive issues.

The authorities tightly control the circulation of foreign journals. In the 1980s, the Paris-based weekly political magazine Jeune Afrique that dealt with African affairs (and had a large readership among the Algerian educated class) was banned. The French daily Le Monde and other French publications were tightly controlled and periodically seized for carrying articles the government found objectionable. However, there were always ways for Algerians to obtain such "popular" issues.

For the most part, Algerians prefer watching foreign TV channels such as the Arabic channels MBC, ART Al-Jazeera,

News Agencies

Algeria has one news agency. The Algerian Press Service (APS) is located in Algiers and is run by the state. APS was founded in 1961. In 1994 it launched its first computerized editorial office and in 1998 its satellite broadcast. The agency is represented in twelve foreign capitals: Washington, Moscow, Paris, London, Brussels, Rome, Madrid, Cairo, Rabat, Tunis, Amman and Dakar.

Broadcast Media

Television and radio are public institutions run by the Algerian government. The Algerian television channel (ENTV) and the three main radio channels maintain regular news service and are the channels of the dissemination of official political discourse. The television presents news in three languages, Arabic, French and English.

The three national radio channels are: Channel 1 (Arabic), Channel 2 (Berber), and Channel 3 (French and some English.) Numerous regions of the country have their own radio stations.

Electronic News Media

Most newspapers are available on the Internet. In Algeria, journalists at the much-censored La Nation were able to post an edition of the weekly at the web site of Reporters sans Frontiéres , a French freedom of expression organization, after La Nation closed its doors in 1996.

When private dailies in Algeria went on strike in October 1998 to protest pressure from state-run printing presses, they published bulletins daily on the Web to mobilize support for their cause.

Algerians can visit numerous web sites mounted by Islamist groups that are banned and have no legal publications inside Algeria, including the Salvation Islamic Front ( Front Islamique du Salut—FIS .)

Perhaps the most defiant use of the Internet in a country without a freedom of the press is the use of the Web as a substitute for censored media. Newspapers censored in Algeria have placed banned stories online, where they circulate widely to the Algerian emigrants and foreigners.

Education & TRAINING

In addition to journalism schools, a number of training opportunities are available to practicing journalists. For instance, in 2001 the U.S. Agency for International Development funded a one-week training session in Algeria for 15 print journalists. This training focused on investigative reporting in the areas of human rights and rule of law, as part of a 15-month project implemented by the RIGHTS Consortium and headed by Freedom House .

Summary

Algerian press, despite the controversies and the bad publicity it received in the nineties, is considered one of the freest in the Arab World. Since 2000, no journalist has been jailed, killed or threatened, and no newspaper has been shut down. The restrictions placed on the press protect the sovereignty of the state; therefore any defamation or personal attack against government and military officials is punishable by imprisonment or fines. The government contends that journalists must choose to use the government presses and respect its laws, or get their own presses. An argument deemed fair to some and unfair to others. While the current political climate is improving, journalists in Algeria stand to meet higher standards of practice to complete with western sources of information as most publications lack objectivity. More importantly, it must find a way to sustain independent financial support so as not to rely on the over conditional government sources needed to disseminate information.

Significant Dates

- 1998: National Union of Journalists is created. The state printers suspend the printing of several privately owned daily newspapers. The state requires journalists to obtain agreement of the authorities before publishing any information dealing with issues regarding security. Physical attacks on journalists that started in 1993 have receded.

- 1999: Early elections. Mr. Bouteflika is the uncontested new President of the Republic.

- 2001: New libel law that would penalize defamation against President Abdel Aziz Bouteflika or other senior government and military officials by imprisonment of up to one year and fines of 250,000 dinars (US $3,500).

Bibliography

Committee to Protect Journalists. Attacks on the Press . 1996. Available from http://www.cpj.org/

Chagnollaud, Jean-Paul, ed. Parole aux algériens: Violence et politique en Algérie . (Essays by Algerian journalists, politicians and ordinary citizens). Paris: Harmattan, 1998.

Faringer, Gunilla L. Press Freedom in Africa . New York: Praeger, 1991.

International Press Institute. Algeria: World Press Review . 2001. Available from http://www.freemedia.at/

Mahrez, Khaled and Lazhari Labter. 1998 Report on the Situation of the Media and the Freedom of the Press in Algeria , International Federation of Journalists Algiers. 1999. Available from http://ifj.org/

Rugh, William A. The Arab Press: News Media and Political Process in the Arab World . Syracuse University Press: Syracuse, 1987.

Smail, Said. Mémoires torturées: un journaliste et un écrivain algérien raconte . Paris: Harmattan, 1997

Stone, Martin. The Agony of Algeria . Columbia University Press: New York, NY, 1997.

Stora, Jenjamin. Algeria: 1830-2000. A Short History . Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001.

Waltz, Susan E. Human Rights And Reform . Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

Willis, Michael. Islamist Challenge Algeria . New York: New York University Press, 1996.

Karima Benremouga