Armenia

Basic Data

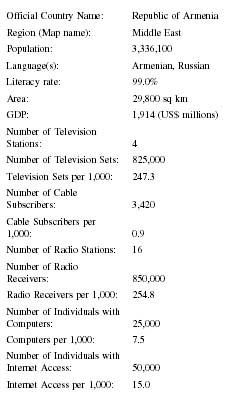

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Armenia |

| Region (Map name): | Middle East |

| Population: | 3,336,100 |

| Language(s): | Armenian, Russian |

| Literacy rate: | 99.0% |

| Area: | 29,800 sq km |

| GDP: | 1,914 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Television Stations: | 4 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 825,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 247.3 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 3,420 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 0.9 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 16 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 850,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 254.8 |

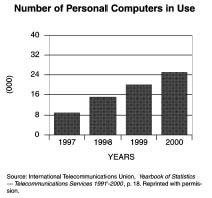

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 25,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 7.5 |

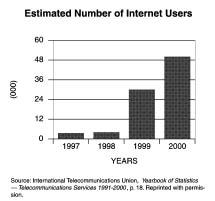

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 50,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 15.0 |

Background & General Characteristics

Within the Republic of Armenia, newspaper circulations are small and the press industry represents a tiny portion of an emerging market economy. The country's tepid investigative journalism accompanies comparable democratic development. In the late 1980s the former Soviet Republic joined others in the move to independence that resulted in the collapse of the USSR. The official proclamation came in April 1991, at which time the International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) was signed and accepted as the basis for developing domestic law. The National Assembly adopted its own Law on the Press and Mass Media in October 1991, guaranteeing the right of access to information, freedom of speech, and a free and independent press. The same principles are embodied in the 1995 Constitution. However, these "guarantees" remain subject to the interpretation of a constitutionally powerful executive. New civil and criminal codes were enacted in 1999, a new broadcast media law in 2000, and a new licensing law in 2001. All three were passed in reaction to the October 27, 1999, terrorist attack on the Armenian Parliament that killed the Prime Minister, Speaker, and six others. The new laws have facilitated the power of government to encroach upon the freedom of the press. However, Armenia also became a member of the Council of Europe in 2001, which carries obligations to guard against threats of excessive state powers restricting a free and independent media.

Armenia's Department of Information registered 642 newspapers and 166 magazines in 2001, but only 150 of these were regularly active. It is safe to say that total newspaper circulation in the Republic is very limited, even though numbers are extremely unreliable. They are based on print runs rather than on actual sales, providing the opportunity to manipulate them for economic gain.

Dailies are issued five times a week, Tuesday through Saturday. Of the 47 registered dailies, the Department of Information estimates a total circulation of only 40,000 copies, or about 1 copy per 83 persons. The major papers circulate between 2,000 and 6,000 daily copies. Many papers circulate only in the several hundreds. Non-dailies may appear two or three times a week, weekly, monthly, or irregularly. Non-daily circulation numbers can run comparatively higher, such as the 30,000 copies for the crime reporting weekly 02 (Police Messenger), a publication of the Ministry of Internal Affairs.

Armenia has no newspaper chains. Private media groupings are only beginning to appear. Nonetheless, newspapers are privately owned, with the exceptions of Hayastani Hanrapetutyun (Republic of Armenia, in Armenian, circulation 6,500) and Respublica Armenia (in Russian, 3,000). Both are joint ventures between the National Assembly and the newspaper staffs, founded in 1991. Ownership of other papers is organized in corporations of both open and closed joint stock companies. The media industry is structured in a manner that separates newspaper editorial offices from the printing and distribution services. Both of the latter were state-owned monopolies until the privatization process that began in 2001. Newspapers operate with extremely limited resources, and therefore none are completely independent of patronage from political parties, economic interest groups, or wealthy individual sponsors. Private ownership of the print media suffers from a lack of self-sufficiency due to low circulation and weak advertising markets, as well as the little revenue generated by advertising.

The media industry is concentrated in the capital city of Yerevan. Some rural regions of the country see no newspapers at all, and other areas have print runs as low as 100 copies. Newspapers address a limited and elite audience: a mere 5 percent of the population takes its news from papers. Broadcast media represents the widest market share: radio at 10 percent and television commanding 85 percent. Most media organizations, and particularly newspapers, either represent a definite orientation toward some particular political party, or express views constrained by the need to retain their financial sponsors. Low circulation numbers reflect the small target audience. This allows newspapers to be sponsor-oriented, as opposed to reader-oriented. Profit expectations are low, and subsequently business investment and advertising are low as well. In 2002, after a decade of independence from Soviet rule and exposure to the process of emerging markets, the newspaper industry still did not operate as a profitable business.

Armenia is one of the most ethnically homogeneous regions of the former Soviet Union: 96 percent Armenian; 2 percent Russian; 1 percent Kurdish; and 1 percent Yerdish. In 1993, with the outbreak of conflict over the Nagorno-Karabakh Armenian enclave within Azerbaijan, most of the Azeri population, formerly 3 percent of the total, returned to Azerbaijan. The Armenian enclave community has tried to secede and attach itself to Armenia, but the international community would not accept the move. The Republic's literacy rate has been nearly 100 percent since the 1960s, a fact that makes low circulation rates most disappointing, as does the 3,000-year-old literary culture of the Armenian people.

According to tradition, the ancient country was founded around Lake Van, by a descendant of Noah known as Haik, and remained independent for centuries under Haikian Kings. The first historical mention of Armenia dates to the ninth century BC, with Assyrian inscriptions referring to Urartu, or Ararat. The high rugged mountains and deep fertile valleys lie at the convergence of the Anatolian, Iranian, and Caucasus plateaus, where the headwaters of the Tigris, Euphrates and Araxes Rivers take rise. It has been a land frequently invaded, conquered and divided among various regional powers since ancient times: Assyrians, Medians, Persians, Parthians, Macedonians, and Romans.

Armenians converted to Christianity very early, and formed the world's first Christian state in AD 301. The Armenian Apostolic Church then played a principle role in establishing and preserving the literary traditions of the language. There was a national alphabet by the fifth century. Grabar, the classical religious language, was also the written language of the Armenian cultural community, which drew its identity based on this linguistic distinctiveness and the adaptation of ancient myths to it. The early Christian state lasted until the seventh centuries. The Bagratid Golden Age ran through the ninth and tenth centuries. Beginning in the eleventh century a series of invasions, migrations and deportations led to the dispersion of Armenian communities outside the historic home-land. Nevertheless, the Kingdom of Lesser Armenia, or Cilicia, in the southeast corner of Anatolia, lasted from the twelfth to fourteenth centuries. Cilicia fell to Genghis Khan, and then was destroyed by Tamerlane. By the sixteenth century, when the Ottoman Empire ruled, most Armenians in eastern Anatolia survived as peasant farmers. Diaspora communities had resettled in Istanbul, Smyrna, and various cities along the eastern shores of the Mediterranean, becoming artisans, traders and moneylenders.

Trade and commerce led to growing Armenian communities in various regional centers from India and Persia, to the Levant, across the eastern Mediterranean basin and into Europe. The successful Armenian Diaspora drew upon commercial skills, polyglot capacities, and international contacts. Wherever they went, their clerics and intellectuals took the Armenian literary traditions with them. The fourteenth century Dasatun (Scriptorium), located in Aleppo, was famous for the art of calligraphy and illumination of liturgical, canonical, and other religious manuscripts. It maintained special workshops for the manufacture of parchment and paper, ink and pigments, and the binding of manuscripts. The tradition of copying Armenian liturgical books began to decline after the seventeenth century, however, with the popularization of printing.

The first Armenian-language printing establishment was founded at Venice in 1565. Papal restrictions on liturgical works led to it being moved to Istanbul in 1567. Still, more than one hundred Armenian titles were published in Europe between 1695 and 1777. The Armenian printing press in Amsterdam, founded in 1660, produced the first printing of the classical Bible in 1666, and functioned for 57 years free from Papal restrictions. The New Julfa community in Persia printed their first book, Saghmor (Psalms), in 1638, followed by Harants-Vark , (Lives of the Church Fathers) in 1646. The first Armenian newspaper was published at Madras, India, in 1794, 60 years before any would appear in the homeland. From 1794 to 1840, only 15 Armenian journals appeared throughout the world. Between 1841 and 1915, however, 675 new Armenian periodicals were published. The boom resulted from the linguistic innovation of a Benedictine order of Armenians founded by the monk, Mkhit'ar of Sebastia.

The Mekhitarist innovation fundamentally altered Armenian literary expression by producing a vernacular, Ashkharabar, which became the medium of an increasingly nationalistic movement. Cultural and political revival in the late nineteenth century generated formation of secret revolutionary societies. Newspapers assumed the role as organs of political parties.

The first journal printed in the new vernacular was Ararat (Morning), published in Tiflis in 1849. The political party Armenakan was founded in France in 1885 and published Armenia in Marseilles. In the Caucasus, Mshak (Cultivator) was printed between 1872 and 1920. Zang (The Ring) was an organ of the Hnchakists political party and published from 1910 to 1922. The Dashnak party published its journals Ararat from 1909 to 1912 and Ayg (Dawn) from 1912 to 1922.

After a history of subjugation to other powers, Armenia revived as an independent state in May 1918. It did not last long, caught between the forces of a Nationalist Turkey and a Bolshevik Russia. One million Armenians were lost to a holocaust engineered by the emerging Turkish Republic. The Red Army installed a communist-dominated government, the Transcaucasian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic, that combined Armenia with Azerbaijan and Georgia. The printed press came under strong central control from Moscow, which lasted until the Soviet Union's demise. The Russian language was also imposed.

The circulation numbers of Soviet-era print media were far larger (in the tens of thousands) than the numbers of the infant private press in the transitional environment of the early twenty-first century. However, there has been an explosion of journalistic activity. In the 1980s, perestroika and glasnost permitted the public discussion of issues as well as access to some information. A language and cultural revival inspired the awakening of national consciousness, and the creation of dozens of new journals and newspapers. Armenian replaced Russian as the primary language in schools and newspapers. The push for greater autonomy, democracy and loosening of Russian political domination began in 1987-88. Despite this encouraging environment for explosive journalistic growth, the story also includes many failed enterprises and defunct newspapers. In 1993 there were thirteen major Armenian language magazines and journals covering such topics as science and technology, politics, art, culture, and economics, one satirical journal, one journal for teenagers, and one for working women. In early 1994 the Ministry of Justice reported twenty-four magazines, nine radio stations, twenty-five press agencies, and 232 active newspapers, compared to the 150 that existed in 2002.

The vast majority of news outlets are located and based in the capital of Yerevan. The circulation of 40,000 daily newspapers is well down from the 85,000 reported in 1995. News is comprised of political reporting on government and parliament, and content extends to the arts, culture, religion, sports, and some limited foreign news. The major privately owned national dailies offer a wide variety of opinions, but newspapers in general do not encourage investigative reporting. Only one newspaper, Delavoy Express (Business Express), concentrates on business and economic news. The situation of careful criticism and no aggressive investigative reporting has been exacerbated by the October 1999 attack on the Armenian National Assembly, as well as by the onslaught of the war on terrorism governments internationally have confronted since September 11, 2001.

The major daily papers in the Republic, in addition to those mentioned above, include:

- Aravot (Morning): established in 1994 by editorial staff. (circulation 5,000-6,000)

- AZG (Nation): founded in 1991, centrist, coverage of Diaspora. (4,000)

- Hayots Ashkhar : founded in 1997 by private owner, politicized. (3,500)

- Haykakan Zhamanak : founded in 1997 by the Democratic Motherland Party and the Intellectual Armenia, a social-political organization. (2,500)

- Yerkir (Country): founded in 1991 by the Armenian Revolutionary Federation Dashnaksutyun (ARF), commonly known as Dashnak; covers religion and the activities of the party; one of the media outlets closed when ARF was suspended by presidential decree in 1994, prior to national elections the next year; resumed publication in 1998 when ARF reinstated. (2,000)

All are printed in either A2 or A3 format, range from 8-16 pages, and have an average price of 100 drams (about 20 U.S. cents).

The major non-daily publications include:

- Ayzhn : organ of the National Democratic Union (NDU) issued weekly. (4,000)

- Dzain Zhoghovrdi (Voice of the People): a weekly established in 1999 as a joint-stock company, issued and financed by the People's party. (3,000)

- Golos Armenii (Voice of Armenia, in Russian): covers news from Russia with an opposition, left-wing orientation. (5,230)

- Garant : a weekly entertainment journal. (30,000)

- Grakan Tert (Literary Paper): issued by the Armenian Union of Writers.

- Hay Zinvor : issued weekly by the Ministry of Defense. (10,000)

- Hayk : founded in 1989 as an organ of the Armenian Pan-national Movement (APM); features party news, entertainment, and foreign news. (3,500)

- Iravunk (Law): founded in 1989; published without interruption. (7,000-12,000)

- Kumairi : printed in Armenia's second city of Gyumri, suffers frequent interruptions, depends on local authorities for financing. (1,000)

- Novoye Vremia (New Time, in Russian): centrist with financial support from a private Moscow-based businessman. (3,000-5,000)

- Nzhar : published weekly by the Ministry of Justice.

- Riya Taze (New Way): a Yezidi ethnic weekly.

The primary printing method in the early twenty-first century remained offset printing. Computer-based (electronic) typesetting has become more popular as imagesetter systems have been introduced to Armenia. The state-owned publishing and printing house, Tigran Met, formerly known as Periodica, was privatized in 2001 and now functions as a commercial enterprise. There are still government-held shares, but no visible government intervention. Tigran Met remains the largest facility, although there are some 20 printing companies registered with the Ministry of Justice; most are very small.

The price of newsprint is a major portion of printing costs. Armenia has no local production and imports newsprint from Russia. Costs are double those in Russia, due to the small market size and transportation costs. Newsprint in Armenia averages $1,200 per ton. Of course, the larger the volume of the purchase, the lower the price, which benefits Tigran Met. The Armenian print media consume 51 tons of newsprint per month; down from Soviet-era figures as high as 920 tons. The average print run fell from 185,000 copies in 1988 to 5,000 in 1997.

The Soviet-era system of subscriptions for newspapers and magazines ceased to exist in 1993. The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, and subsequent economic blockade and gasoline crisis, brought deliveries to a stop and the system of subscriptions evaporated—another factor contributing to low circulation numbers. The state-run Hayamamoul distribution company began the privatization process in 2001. Since regaining independence the distribution network has consisted of a system of some 200 kiosks scattered throughout the capital city, Yerevan, and in some of the other regions. Kiosk operators are guaranteed a minimum income (U.S. $20-30 per month) based on sales. There is a financial penalty for unsold papers, so Hayamamoul has developed a "no return" policy that establishes a set circulation amount and a guaranteed low cost on returns. The alternative "return" policy gains the paper a higher percentage of kiosk sales, but there is a high collection cost incurred on returned papers. Most papers choose the "no return" policy for the guaranteed revenue. Corruption has worked its way into this process, as circulation numbers are often kept artificially low while the printing house prints overruns (beyond the agreed number), sells them, and keeps the profits. The printing process also serves as a form of censorship, as print runs will be stopped if they contain controversial articles.

Economic Framework

The bleak economic environment in the Republic of Armenia since regaining its independence is yet another factor hindering the media's reformation and depressing circulation numbers. The prevailing conditions result from a combination of tensions that include: the transition from Soviet political and economic centralization to market-based economics and democratic politics; the 1988 earthquake that killed 25,000 and left 500,000 homeless; the ethnic tensions in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan; and the global war on terrorism. These macro-economic social and political factors, along with the government's inability to account for and tax as much as 40 percent of economic activity, combine with the micro-economic realities of low newspaper readership and lack of a viable advertising market, to create a difficult environment for the Armenian press.

Limited resources and readership act as overwhelming constraints on the development of advertising revenues, the lifeblood for any independent media. Political sponsorship or some form of patronage of the media is an accepted substitute for business performance. Ownership often remains hidden. This lack of transparency affects the media in that professional standards tend to give way to economic survival. Often a paper's allegiances can be deciphered through the biases in the reporting.

By signing the Alma-Ata Declaration in December 1991, Armenia became a founding member of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), an economic community, if not political union, of former Soviet Republics. In reaction to the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, Turkey and Azerbaijan have imposed an economic blockade against Armenia for a decade. The longer the status of the enclave remains unresolved, the longer it continues to disrupt economic development.

Armenia has claimed 3.5 percent to 5.5 percent annual economic growth between 1993 and 2002. This is misleading, because there has been little improvement in investment, exports, or job creation. The growth numbers suggest a supportive climate for business, but they cloak a failure to create improved conditions for consumers.

There is serious income inequality and widespread poverty, and levels of unemployment and emigration are rising. The government reports unemployment at 12 percent, but it is at least double the official number. Estimates are that nearly half the population lives below the poverty line, and in need of government assistance.

Newspapers also must search for funds to pay for their high printing and other production costs. Extremely limited resources mean dependence on patronage from interest groups or individuals. Editors turn to sponsors as the most common way of meeting financial need. Businessmen contribute to pro-government newspapers for political connections. Sponsors solidify government connections in seeking preferential consideration. Paternalism and clientalistic networks permeate the industry.

The National Assembly tried to encourage journalistic expansion through tax policy. The print media receives an exemption from the value-added tax (VAT), legally stipulated in a 1997 law. However, the editorial offices pay the tax indirectly in costs imposed by the printing houses, for whom the exemption does not apply.

Economic assistance from foreign aid programs and the diaspora community has been on the increase. George Soros' Open Society Institute has invested in media projects since 1996. In 1999 the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) contributed to the media law reform program. The International Research and Exchanges Board (IREX) has introduced technical assistance through its Pro-Media program. The Eurasia Foundation helped establish Gind, a private publishing house, to challenge Tigran Mets' monopoly. In May 2001 Gind discontinued Haykakan Zhamanak because of unpaid debt. Questions about political influence in the decision have been raised. The European Institute for the Media (EIM) is a non-profit association under German law working towards integrating the CIS states into a civil digital society by developing cross-border media. EIM also conducts programs to advance research, the media's relationship with democracy, the European television and film forum, and a library documentation center. The funding comes from a variety of European sources.

Press Laws

Constitutional and legal protections for journalists exist in Armenia, but enforcement is ambiguous and uneven. Based on the ICCRP, the 1991 Law on the Press and Mass Media conforms to many accepted European standards. Article 24 of the Constitution, established in 1995, reiterated the protections of freedom of speech and press. Armenia's acceptance into the Council of Europe in 2001 should help provide structure and oversight in protecting freedom of speech. This legal and regulatory framework supports an independent media in principle. In practice the application of constitutional guarantees has fallen far short of expectations.

The registration of journalists and news agencies is mandated in the 1991 law. In 2001 a law on licensing was enacted that requires re-registration of all media companies. The cost has been a burden for all newspapers, which are forced to operate on narrow margins as is.

Article 2 of the press law forbids censorship. However, Article 6 imposes restrictions on types of information that can be published, e.g., appeals to war, violence, and religious hatred. The law also prohibits the publication of "false or unverifiable information," a clause often invoked by the government in its dealings with the media. There exists further invitation for abuse, manipulation, and intimidation on part of the government in any conflict with journalists over the issue of revealing sources. In court cases sources must be revealed, which encourages self-censorship. Libel is a criminal offense in Armenia. However, it is vaguely defined, and this leaves journalists facing legal suits and criminal arrest for conducting their professional responsibilities.

Censorship

There is no official censorship, but freedom of expression in the press is limited. Armenia's judiciary is hindered in protecting press freedoms by the executive's oversight capacity, and its ability to restrict the jurisdiction of the courts. Judges and prosecutors are dependent on the executive for their employment. Constitutional human rights and press freedoms are, therefore, not safeguarded. The judicial system itself continues to be in transition: in 1999 both prosecutors and defense counsels began a process of retraining and recertification as mandated by the Constitution.

Even though the opposition press criticizes government policies and leaders, journalists see the 1991 press law as inadequate for both their own personal protection and the development of their profession. Criminal defamation, as covered in Article 131 of the 1999 Criminal Code, is a strong instrument for government restriction on press freedom. Fines and compensation for damages are steep, and punishment now includes imprisonment for up to three years. As a result, journalists are tepid investigators, hoping to avoid the retribution some have experienced in recent years on the part of powerful officials and other individuals. The case of Vahram Aghajanian in Nagorno-Karabakh is a reminder that the enclaves' self-proclaimed authorities are less restrained than in the Armenian Republic itself. In June 2000 Vahang Gnukasian suffered incarceration and was beaten at the Interior Ministry, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ).

Self-censorship is common in reporting on such issues as the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, national security, or corruption. In covering domestic policy and political issues, self-censorship has been reinforced by the strengthened libel laws in the criminal code. The news media is not required to reveal sources under the 1991 law, except when involved in a court case. To avoid appearing in court, sources are rarely cited, and "news" stories read more like commentaries than reporting. The need to retain or seek economic patronage is another important factor in self-censorship.

The Armenian journalistic community itself has not developed effective mechanisms to protect itself. An absence of self-regulation norms promotes a false sense of freedom, but gives room to critics who desire to shorten the media's pen. Because journalists have determined no rules themselves, such cases go to the courts.

State-Press Relations

The constitutional protections and institutional legal structure defining the role between the state and a potentially free and independent press have been taking legislative form for a decade. The printing and distribution agencies, however, have until recently been state-owned. The privatization process was advanced in 2001, but problems persist and success is yet to be verified.

The pursuit of journalism as a profession has been answerable to the government's protection of state secrets and maintaining state security. There are reported transgressions against journalists and media firms by security forces as well as privately hired thugs. Both have delivered beatings and other forms of intimidation to journalists, including fires and destruction of editorial offices. These crimes are rarely solved or even thoroughly investigated, and because the judiciary is constitutionally submissive to the executive, journalistic independence has only uncertain state protection.

Nine political parties were banned prior to the 1995 Parliamentary elections, which resulted in the closure of the media organizations owned by or associated with those parties. The politics of media control was evident in the case of Dashnak's printing house, Mikael Vardanyan, a Canadian-Dashnak joint venture, which was suspended, closed, and looted. Operations remained closed for four years, until re-legalized in February 1998. Similar transgressions preceded the 1999 election.

The degree of political influence on the content of newspaper reporting has intensified since the 1999 attack on the National Assembly. The attack has brought increased tensions between the government and the press, and even among the press themselves. The Yerevan Press Club's extensive media-monitoring project has determined that an "information war" over differing opinions about the parliamentary attack began in early 2000. One group, supported by the political opposition, linked the terrorist activity to associates of President Robert Kocharian. The other group has accused the investigators of political involvement and bias, and views Kocharian as the only guarantor of stability and justice. The increased government monitoring of the press, and demand for the names of sources, has only served to increase self-censorship on the part of journalists.

Corruption and lack of transparency continue to characterize the environment in which the media must operate. Accepting bribes is a criminal offense, punishable by up to 8-15 years imprisonment, plus confiscation of personal property for repeated crimes. Despite these severe penalties, bribery remains widespread and the most common form of media corruption. The shadow economy and money-making potential of influence-peddling serve to advance the hidden and non-transparent exercise of power through manipulation of the press.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

There are no legislative restrictions on access to international news coverage and reception of satellite television, and no censorship of imported printed materials. The free flow of information is protected under the ICCPR and membership of the Council of Europe. Foreign reporters must register with the Ministry of Justice; a presidentially appointed commission conducts licensing of foreign media companies. There is a variety of Russian broadcasts and printed news (Russian is the second language for 40 percent of the population), as well as news presented in translation from the BBC, Euronews, and CNN.

Diaspora Armenians support organizations and associations that produce newspapers and published materials both in the Republic and throughout the world-wide diaspora communities. One-sixth of the 6 million Diaspora population resides in Russia. The Soviet regime had banned diasporic activity in Armenia. There is an active relationship between Russian media and shareholders, whether Armenian or not, and the Armenian Republic. The flow of information, however, is predominantly from the homeland to the dispersed communities, rather than the reverse.

News Agencies

The Armenpress News Agency is the state service that dates from the early Soviet era. It covers political, economic, and cultural news from the homeland and abroad in Armenian, English, and Russian ( http://www.armenpress.am ).

There are about twenty-five private services registered with the Ministry of Justice. They cover news both in the Republic and the Armenian Diaspora Communities. Some of the major services include the following:

- Agragil, an English-only service covering daily news from Armenia; it feeds Azg , YerkirHayastani Hanrapetutyun, Respublica Armenia , and Golos Armenii. ( http://www.aragil.am )

- The Armenian Daily News Service, a service offering news, press reviews, and articles from columnists on domestic issues, the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, the Transcaucasus region, and the Armenian Diaspora. ( http://www.armeniandaily.com )

- ARKA, a service created in 1996, specializing in financial, economic, and political information in English and Russian. ( http://www.arka.am )

- Noyan Tapan, a multi-media company and information center offering an advertising service and video documentary programming. ( http://noyan-tapan.am )

- SNARK, the first independent news agency in Armenia and the Caucasus when it was established in 1991. ( http://www.snark.am )

- The SPYUR Information Service, founded in 1992, offering an information and inquiry service about companies and organizations in Armenia. ( http://www.spyur.am )

Broadcast Media

From its inception in 1991, the law has treated the print media as separate and distinct from the broadcast media. The Law on Television and Radio Broadcasting was adopted in October, 2000, of which several aspects have caused alarm in the industry. The Armenian president is given the exclusive right to appoint all nine members to a governing body that regulates and licenses the media. Thus it is seen as a political tool of the executive. Article 9 requires that television and radio stations devote 65 percent of airtime to locally produced programs in the Armenian language. This has caused concern over the financial burden of production. The libel law's vagueness and threat to journalists applies to broadcasters as well as print media.

In 2002 the Ministry of Information reported 850,000 radios in the country and 825,000 television sets. There were 55 radio stations and 48 independent television companies. All media outlets have been required to register with the Ministry of Justice since re-independence in 1991. The government implemented a re-registration and licensing program in 1999. The same law also prohibited individuals from founding a media company. All programming is in Armenian, although foreign films are shown with Russian translation.

As of 2002 there were two state-owned TV channels. H 1, or National Television of Armenia, was a stateowned closed joint stock company. It was founded in 1954 and was able to reach the whole Republic by satellite. The broadcast day was limited to 6 hours until January, 1999, when it was extended to 15. The second channel was founded in 1978 and made available to the concentrated urban, industrialized and population of the Ararat valley. In 1995 it was named Nork, and has become known for its presentation of a liberal political orientation. Programming on Nork was abruptly stopped in early 1999. It was replaced with programming from the channel Kultura.

Shant TV was founded in April 1994 at Gyumri, the second largest city in Armenia. A new Independent Broadcast Network was founded in 2000 by a consortium of Ashtarak TV, A One Plus, Shant TV, and five other smaller companies. A new channel, Biznes TV, focused on computing, education, and televising courses during the day over the Russian ORT frequency. Biznes operated a professional studio for computer graphic production and produces all its own programming. Broadcast days varied station to station. H 1 had two segments: 9 a.m. to noon, and 5 p.m. to 1 a.m. The independent channel, A One Plus, broadcast 24 hours a day.

Executive control over the licensing process to manipulate the information flow is a blunt political tool. In January, 2001 the government stopped re-broadcasting ORT due to a financial dispute. Broadcast was subsequently resumed on a different frequency when the dispute was settled. Two independent broadcasting companies, A-One Plus and Noyan Tapan, were stripped of their licenses in April, 2002. The action was consistent with past government attempts to quiet opposition ahead of elections. These closures have left Armenia with no major independent broadcast outlets. The frequencies were awarded to other media firms without news broadcasting experience: Sharm, an entertainment company; and Shoghakat, which is associated with the Armenian Apostolic Church.

As a member state of the Council of Europe, Armenia accepted the European Convention on Transforntier Television, which entered into force in March, 2002. The parties are to ensure freedom of expression and information in accordance with Article 10 of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, guarantee reception, and not restrict retransmission of program services.

Electronic News Media

The Internet and Information Technology (IT) have only begun to appear in the beginning of the twenty-first century. The Ministry of Justice registered 43 IT firms in 2001. However, a local business association put the estimate at 200 companies. It is believed 4,000 people were

Education and Training

Armenian universities have provided undergraduate and graduate degrees in journalism since the Soviet era. The system has been characterized by the journalistic theory lingering from the former Soviet system. The transitional institutional reforms taking place in Armenia throughout the 1990s have introduced some significant changes. Curriculum changes are being made in order to improve journalistic professionalism and quality of reporting.

Private professional organizations are working to improve the quality of journalism and the environment that journalists work in. The Armenian Union of Journalists dates back to the Sovietera, and organizes courses for the journalistic community. The Yerevan Press Club (YPC) was established during a seminar organized by the European Institute for the Media in June 1995. The YPC issues a bulletin, organizes press conferences, seminars, and journalism courses. It also monitors the media and operates a press center. The Mass Media Association of Armenia was created in 1997 with the purpose of participating in the privatization process of the print production and distribution companies.

Summary

The demise of the Soviet Union left an unstable political, social, and economic environment in the Republic

The newspaper industry was privatized in 1991, and editorial offices have helped facilitate limited public discourse. Political opposition and criticism of the government has been allowed. However, the print media does not function as an economically viable business. Advertising and circulation revenues are not sufficient to cover the costs of printing and distribution. The transition from a state-supported towards a privately-owned and market-based media has been difficult. In the 1990s there has been an increase in foreign and diaspora aid for the training of journalists. The profession is beginning to show some improvement in the quality of reporting. At the same time, government regulation and surveillance in the name of national security is on the increase. Tension results from the government's need for security and the media's need to protect sources. The legal questions facing the editorial offices only distract them from the effort to increase readership and advertising revenues, as well as begin to engage in investigative reporting. In general, news-oriented papers are not a profitable business. Entertainment orientation of the news and publications enjoy greater profitability. In this regard, Armenia is not unusual.

Significant Dates

- 1991: The Republic of Armenia becomes an independent state with the demise of the Soviet Union.

- 1995: The Constitution of the Republic of Armenia is ratified by referendum.

- 1996: The Law on Advertising enacted.

- 1999: The National Assembly passes new civil and criminal codes; on October 27, the National Assembly is attacked and several government officials were killed.

- 2000: The National Assembly enacts the new Law on Television and Radio Broadcasting.

- 2001: The new Law on Licensing enacted which mandates the re-registration of media outlets.

- 2002: The new Law on Printed Press is under legislative review.

Bibliography

"Armenia." Europa World Yearbook 2001 . Vol. 1, A-J. London: Taylor and Francis Group, 2001.

"Armenia." Media Sustainability Index 2001 . Washington, D.C.: IREX, 2001.

ArmenPress . Available from www.armenpress.am/ .

Azg Newspaper . Available from www.hntchak.com/newsarm.html

Bardakjian, K.B. The Mekhitarist Contributions to Armenian Culture and Scholarship . Cambridge: Harvard College Library, 1976.

Bedikian, A. A. The Golden Age in the Fifth Century: an Introduction to Armenia . New York: Literature in Perspective, 1963.

Berberin, H. Armenians and the Iranian Constitutional Revolution of 1905-1911 . Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2001.

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). International Economic Statistics . Washington, D.C.: GPO, 2001.

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). World Factbook 2001 . Directorate of Intelligence, 2002. Available from www.cia.gov/ .

Chaqueri, C. The Armenians of Iran: The Paradoxical Role of a Minority in a Dominant Culture, Articles and Documents . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998.

European Institute of the Media. Media in the CIS . Dues-seldorf, Germany: European Institute of the Media, 1997. Available from www.internews.ras.ru/books/media/contents.html .

Hovannisian, R.G. The Republic of Armenia . Berkley: University of California Press, 1996.

International Monetary Fund Report on Armenia . Washington, D.C.: IMF Economic Reviews, 1993.

Media in Armenia . Soros, 1997. Available from soros.org/armenia.at/archive97/world.html .

Nercessian, R. Armenia . Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio, 1993.

Noyan Tapan Information and Analytical Center . Available from noyan-tapan.am/.

Open Society Assistance Foundation-Armenia . Available from www.soros.org/natfound/armenia/ .

Suny, R.G. Looking Toward Ararat: Armenia in Modern History . Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993.

Sussman, L.R. and K.D. Karlekar, eds. Annual Survey of Press Freedom . New York: Freedom House, 2000.

Toloyan, Khachig. "Elites and Institutions in the Armenian Diaspora." Diaspora . Vol. 9, no. 1. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000.

UNESCO. Annual Statistical Yearbook . Paris, France: Institute for Statistics, 1999.

United States Agency for International Development. Armenia . Washington, D.C.: GPO, 2000.

World Radio TV Handbook (WRTH) : The Directory of International Broadcasting . Vol. 56. Milton Keynes, UK: WRTH Publications Limited, 2002.

Yerevan Press Club . August 2002. Available from www.ypc.am/ .

Keith Knutson

thanks for your explanation, but I would like to know the complete process of tv station registration in Armenia and eny facility which is available to cooperate with such tv station and braoadcasting.

Thank you

We are "MIG" TV/Radio station located in Vanadzor city, Republic of Armenia. We have a fine project idea, please tell us if we can apply for the Grant program.

Thanks.

Samvel Harutyunyan

MIG TV/Radio, Vanadzor city, Armenia

+374 77474957

+374 55563788 /eng/