Cuba

Basic Data

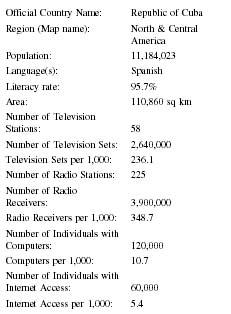

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Cuba |

| Region (Map name): | North & Central America |

| Population: | 11,184,023 |

| Language(s): | Spanish |

| Literacy rate: | 95.7% |

| Area: | 110,860 sq km |

| Number of Television Stations: | 58 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 2,640,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 236.1 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 225 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 3,900,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 348.7 |

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 120,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 10.7 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 60,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 5.4 |

Background & General Characteristics

General Description

The press situation in Cuba ranks as one of the most complicated in the world due to the political and physical distribution of the Cuban people. Since the victory of the Castro-led forces in 1959, a significant Cuban exile community has flourished in the United States, especially in South Florida. This offshore Cuban community has generated a significant volume of information during its decades of exile. Part of their output has been in English, designed for the audience in the United States, while the remainder has been in Spanish, aimed at consumption by the population of Cuba. Similarly, the press offerings on the island, including both the government-sponsored media and those of the opposition, have been divided between those aimed at domestic and international audiences.

The press situation in Cuba is one of the most restrictive in Latin America. Over the more than four decades since the accession of the Castro government, neither freedom of expression nor freedom of the press have existed on the island. The Castro regime maintains a monopoly on information throughout the nation, confiscating the property of independent media and maintaining a policy of constant repression.

The Nature of the Audience: Literacy, Affluence, Population Distribution, Language Distribution

In 2001, the U.S. government estimated the population of Cuba at just over 11 million. Of these, 21 percent were aged 0-14, 69 percent were aged 15-64, and 10 percent were over age 65. The population was estimated to be growing at a rate of .37 percent annually. The ethnic mix of the nation includes 37 percent persons of European descent, 11 percent persons of African descent, and 51 percent people of mixed races. Despite its history of slavery, the significance of race is less of an issue in Cuban society than it is in the United States. Eighty-five percent of Cubans were nominally Roman Catholic prior to Castro coming into power. The remaining religiously identified Cubans included Protestants, Jehovah's Witnesses, Jews, and Santeria.

The government's figure for overall literacy is 95.7 percent of all persons aged 15 and older, although this figure is based on the unique Cuban definition of literacy. In 1961, the Castro-led government initiated a Literacy Campaign that claimed remarkable results, dropping the nation's illiteracy rate from nearly 40 percent to below 4 percent in a single year. In the years since the revolution, Cuban officials have consistently placed the nation's illiteracy rate at figures of three or four percent, a rate better than that in Switzerland. However, the Cuban definition does not conform to world standards for measuring literacy. In the Cuban model, the literacy rate describes the proportion of those persons between the ages of 14 and 44, whom the government believes capable of learning how to read, who could read and write according to a standardized Cuban test. In the early 1980s, when the Mariel boatlift refugees came into the United States, many of them were tested for literacy in Spanish by local school districts for the purpose of placement in the second language programs of American public schools. The results of these tests placed their literacy rate at more plausible levels of between 70 and 80 percent. These and other objective measures of Cuban literacy demonstrate that the efforts of the Cuban government to improve literacy have been effective, although not nearly as effective as Cuban propaganda and UNESCO sources would suggest.

Quality of Journalism: General Comments

The state-employed journalists of Cuba are very literally the voice of the Cuban government. Because of the severe restrictions in content as well as in style that are placed upon these writers and editors, the work is described as "a very somber and unimaginative journalism" by Dr. José Alberto Hernández. Hernández, president of Cuba-Net, a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization based in the United States that works to foster press freedom in Cuba, points out that upon separation from the government-controlled media, an independent journalist, while achieving some freedom of expression, loses access to both ends of the journalistic process. Sources that were once openly available become utterly unapproachable to the independent. Likewise, publication proves elusive to the independent journalist. Therefore the choice for the Cuban journalist is between a dull and highly controlled career within the state-sponsored media or a precarious and difficult one outside of that media.

The most noticeable trait in journalism concerning Cuba is the omnipresent bias. On one side the bias is the pro-government slant found in the government-controlled press organs that flourish on the island and in the scattered press organs around the world that sympathize strongly enough with the Castro regime to overlook its cavalier treatment of press freedom. These press outlets serve effectively as apologists for all Cuban government activities and sounding boards for Cuban-based criticism of the West, especially the United States. However, the bias on the other side of the divide is equally severe. Given the difficulty of serving as an independent journalist inside Cuba, only those with powerful and typically anti-Castro agendas tend to endure the hardships associated with this career. Similarly, a huge amount of writing originating outside of Cuba flows from the exile community in South Florida, from the Radio Martí air-waves and from other anti-Castro activists.

Those who would serve as impartial observers face difficulties from both directions. The Cuban government, while extremely accommodating to those members of the foreign press who they perceive as representing the "reality of Cuba," provide virtually no real access to journalists whom they do not feel they can utilize. Political and bureaucratic opposition to objective coverage of Cuba for American journalists can make the endeavor seem not worth the effort.

Historical Traditions

Cuban journalism traces its history to an early beginning during the Spanish colonial rule, with the first Cuban press put into operation by 1723. The history of the nation's press can be divided into five periods. The first period, the Colonial, reaches from the earliest days until 1868. The second period, the time of the Independence Revolution, spans the period from 1868 to 1902. A third period, the Republican period, runs from 1902 until the overthrow of the dictator Machado in 1930. The third period, the Batista era, lasts from 1930 until 1959. The final and current epoch of the Castro era runs from the triumph of the communist revolution in 1959 up to the present.

In comparison with Spanish colonies in other parts of the world, Cuba developed a printing press at a rather late date. However, compared to the rest of the Caribbean and Central America, the Cuban press came early. The nation's first newspaper, Gazeta de la Habana, began publication in 1782, followed in 1790 by the colony's first magazine, Papel Periódico de la Habana . These early publications and those that came into being over the following century operated under Spanish press laws that had been in place in Spanish America since the late sixteenth century. During the early years of the nineteenth century, Spanish regulations on the press became relaxed, partly due to the decreasing power of Madrid on its distant colonies and partly in response to the political currents flowing from the French Revolution.

The second phase of the Cuban press began in 1869 with the first war of independence, when the colonial government issued a press freedom decree with the aim of gaining favor from the reformist circles. In the months following this decree, a series of reform-minded periodicals began publication, of which the most important was El Cubano Libre, appearing on the war's first day. Other new periodicals included Estrella Solitaria, El Mambi and El Boletín de la Guerra.

In 1895, at the outset of the second war of independence, the most important newspaper of the reform party was Patria, which had been founded in 1892. Providing the spark that began Patria was José Martí, who had earlier written for a wide variety of newspapers and magazines, including La Nación of Buenos Aires and the New York Sun. Journalism provided Martí with his most direct, immediate, and constant form of expression. Martí, who served as the inspiration and organizer of the War of Independence in Cuba, saw newspaper essays as a key force in the development of modernism and the inspiration of his fellow revolutionaries as they struggled to free themselves from Spanish rule.

With the establishment of the Republic of Cuba on May 20, 1902, the history of the Cuban press entered its third period, which lasted until 1930 when the dictator Gerardo Machado was overthrown. During this period Cuban journalism enjoyed a time of prosperity in which at least a dozen dailies flourished in Havana. In the opinion of Jorge Martí, this large number arose due to the ease with which one could start a newspaper or magazine, the willingness of political parties to serve as sponsors, and an overall strong economy. Faced with increasing political opposition and an often-hostile press, in 1928 Machado attempted to co-opt the press by providing significant government subsidies to periodicals in exchange for support. This move prefigured the difficult times to follow.

Machado's fall began in 1930, brought about by earlier economic difficulties and aggravated by the 1933 political instability. With this, the golden days of Cuban journalism faded, brought to an end by the combination of labor unrest from within and the increased government attempts at control from without. The declining state of the Cuban press might have been much worse had it not been for the improvements brought by twentieth-century technological advances. The arrival of steam-powered printing presses and the increased commercial sophistication of the publishers served to expand the journalist's audience and prestige across the country. During this period, a succession of authoritarian regimes which culminated in that of Batista in 1952, exerted increasing control over the nation's press.

In 1959, with the victory of the Castro-led communists, the history of the Cuban press entered its current phase. This phase might be described as simply a continuation of the movement toward government domination and control of the press that began in 1930. The four decades following the Cuban revolution have been marked by very tight government authority over all press outlets. Although opposition has worked throughout this period to counter the government's propagandistic journalism program, only in the 1990s with the emergence of the Internet as a new medium has independent journalism began to pose a significant challenge to the government control of information.

Although often castigated by the Castro regime, the American press played a vital role in the establishment of an independent Cuba by leading the charge toward America's entry into a war with Spain. At the forefront of this effort stood two giants of American journalism, publishers William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer. Both men saw in the conflict with Spain a rare opportunity for increased circulation of their newspapers. Correctly perceiving in the spirit of the day an increased patriotic sense, the two publishers directed their newspapers to publish sensational anti-Spanish stories. These stories were often illustrated graphically by some of the most gifted artists of the day, including Frederic Remington, and written by top quality writers such as Stephen Crane. Working in competition with each other, Hearst and Pulitzer ironically worked together in creating a war frenzy among the American people as they reported the alleged brutality of the Spanish toward the Cuban rebels. At the same time, the violent acts committed by the Cuban rebels were rarely mentioned in the papers' coverage. When the USS Maine exploded in Havana Harbor, the pro-war coverage instigated by Hearst and Pulitzer had sufficiently built national war sentiment that President McKinley felt it a political necessity to bow to pressure and enter into a war with Spain.

While the press under the Castro-led government from 1959 to the present has received significant criticism from world press organizations and advocates of a free and open press, it should not be forgotten that a history of free expression is not found in years before 1959. Where the Castro regime has used direct state control of media outlets since the 1960s, the previous governments exercised control of a privately owned media through frequent closures of newspapers and censorship. The nation's 1940 Constitution reacted against the censorship that had plagued the Cuban press since 1925, providing strong protections for the press and free expression. Despite these provisions, ensuing rulers returned to the censorship practices of their predecessors, effectively ignoring the law. Fulgencio Batista, who came to power in a coup on March 10, 1952 established very strong censorship during his nine years of leadership. Censorship under Batista was explained as a response to the threats posed by the rebel movement that would eventually un-seat him. The Union of Cuban Journalists (UPEC), in discussing the issue of press freedom, asserted that "press freedom only existed in the colonial and republican life of Cuba for the powerful ones and rulers."

During the difficult economic times of the 1990s, significant problems afflicted the Cuban press as a result of the ongoing financial distress of the nation. Budgetary shortages brought about drastic consequences, including a 40 percent reduction in hours of radio and television programming and an 80 percent reduction in the budget of the print media.

Foreign Language Press

Although many of the national press services in print, broadcast, and digital media are published with English-language counterparts aimed primarily at international consumption, no significant non-Spanish press exists on the island.

Leading Newspapers

Three national periodicals circulate in Cuba. The newspaper with the largest circulation is Granma , which since its founding in 1965 has served as the official news organ of the Communist Party. The other two national publications are Juventud Rebelde and Trabajadores . Regional newspapers are published in each of the fourteen provinces of the island. Also, the nation boasts various cultural, scientific, technical, social science, and tourism magazines, which appear at various intervals.

The most important newspaper in Cuba is Granma . In 1998, Editors and Publishers International Yearbook placed the circulation of the daily at 675,000, which ranked it as the 88th most widely circulated newspaper in the world. The international reach of Granma expanded significantly with the advent of the Internet. The website Digital Granma Internacional brings much of the print edition's content to the web, presenting it in Spanish, English, French, Portuguese, and German. In all of its incarnations, the propaganda role of Granma is impossible to avoid. Typical front-page headlines include roughly equal numbers of stories vindicating and celebrating government policies and position along with frequent stories censuring the political leadership of the United States for perceived abuses. In both its print edition and Internet counterpart, this daily newspaper contains national and international news, cultural reporting, letters, sports, and special thematic features.

Juventud Rebelde, the nation's newspaper with the second highest circulation is, as all professionally produced publications on the island, controlled and created by the government. Under the editorial leadership of Rogelio Polanco Fuentes, the newspaper has maintained a focus on news about and for Cuban youth culture. In pursuing this aim, Juventud covers many of the same stories as the more adult-oriented Granma . Comparisons between the coverage of stories in these two leading newspapers show that the Juventud articles tend to be briefer, composed of shorter sentences, and drafted with a less challenging vocabulary. The daily runs a regular feature entitled "Curiosidades," in which brief, peculiar news stories of the sort that the U.S.'s National Public Radio Morning Edition runs at half past the hour are related. Juventud, like its adult-oriented counterpart Granma , also covers cultural and sporting events but from a more youth-focused angle. The focus on popular music, nearly nonexistent in Granma , is a prominent example of this contrast. However, rather than pandering to a youth culture, Juventud actively works to indoctrinate the young people of Cuba into a belief system that serves the state's interests. The newspaper runs regular articles celebrating the heroes of the revolution and frames pieces in such a way as to encourage its young readers to identify with these heroes.

A prime example of the journalism of identification practiced by Juventud Rebelde can be seen in the ongoing coverage throughout late 2001 and 2002 of the incarceration within the United States of the so-called "Cuban Five." Rene Gonzalez Sehwerert, Ramón Labanino Salazar, Fernando Gonzalez Llort, Antonio Guerrero Rodriguez, and Gerardo Hernandez Nordelo, were arrested in the United States on charges of espionage against South Florida military bases. The Cuban government and the five men themselves have claimed since their arrest in September 1998 and throughout their trial and imprisonment that they were merely attempting to monitor the activities of right-wing anti-Cuban groups in Florida. The five were convicted in June 2001. Since that time, the Cuban press has provided daily focus on these men, branding them the "five innocents" and portraying them, after September 11, 2001, as fighters against terrorism.

The differing coverage of this issue between Granma and Juventud Rebelde is illustrative of the audience differences between the two dailies. In Granma , the focus of the stories regarding these five prisoners has been in placing them into a larger context of both history and world politics. The five are compared favorably with Cuban heroes of old and their actions are portrayed within the context of a longer struggle against the imperialist forces of the United States. In Juventud Rebelde , the political and historical context is less important. Instead, readers are urged to identify with these young men. In fact, the young age of the prisoners is a regular focus in Juventud , despite the fact that, in their mid-to late thirties, most of these men are considerably older than the readership of this newspaper. Juventud also places much more emphasis on the families of the prisoners.

The third national publication in Cuba is Trabajadores (Workers), which is much more political and polemical than either Granma or Juventud Rebelde . As the official organ of the government-controlled national trade union, Trabajadores also is the most noticeably and consistently Marxist in orientation of the three.

Economic Framework

All of the official media outlets on the island of Cuba are controlled by and almost exclusively funded by the government. The nominal subscription fees charged to Cuban nationals for the three major print media fail to cover the marginal production costs of the publication. Since the advertising carried within the newspapers is essentially all purchased by the state, the subsidies provided to cover the shortfall in the publications' budgets take the form of inter-agency transfer payments. Subscription rates for a weekly edition of Granma Internacional cost US$50 per year, again an amount insufficient to cover the cost of production. Broadcast media are similarly supported by government funds. The amount of the subsidies paid to the various press organs is not public knowledge.

The government controls some 70 percent of all farmland on the island as well as 90 percent of production industries. Although the government brings in considerable revenue from exports, especially sugar, Cuba's economy has been in deep difficulty since the early 1990s. Credits and subsidies from the Soviet Union totaled an estimated US$38 billion between the years 1961 and 1984. As much as US$4 billion was transferred from the Soviet coffers to those of Cuba during the late 1980s. The collapse of the Soviet bloc, which deprived Cuba of both its leading aid donor and trade partner, severely damaged the nation's economy. During the early 1990s the annual gross national product was about US$1,370 per capita. The annual government budget included approximately US$14.5 billion in expenditures, offset by only US$12.5 billion in revenues.

A journalist can earn a respectable income by Cuban standards; however, the salaries paid to all Cuban workers are problematic. Wages have not risen markedly over the 40 years since the revolution. In addition, wages paid in Cuban pesos are of questionable value as shortages of goods in the nation's stores leaves consumers with no use for their earnings. Since the peso is not a widely recognized currency, even those workers with access to external markets find themselves unable to participate.

The economic structure of the non-governmental press is even more difficult. Since the independent journalists working on the island are not able to sell their work in any form that could provide sufficient income for personal support, most of the independent journalists work out of a sense of devotion to their profession rather than for hope of material gain. Those independents who do sell their work to paying markets abroad run the risk of imprisonment.

The anti-Castro press/propaganda structure centered in South Florida, while carrying advertisements, is largely a political construct. Advertisers support these media not because of the benefit that the advertisement promises to their businesses but because of their devotion to the anti-Castro cause.

Press Laws

Constitutional Provisions & Guarantees Relating to Media

Article 53 of the 1976 Cuban constitution recognizes freedom of both expression and the press, but subordinates and limits those freedoms to the "ends of the socialist society." Constitutional Article 62 limits press freedoms further, and Article 5 grants to the Communist Party on behalf of the society and the state the duty to organize and control all of the resources for communication in order to realize the benefit of state.

Summary of Press Laws in Force

There is no formal press law in Cuba, and aside from the vague statements in the constitution, press freedom is not guaranteed legally. The Communist Party, according to a resolution approved by the first party congress in 1975, regulates the role and function of the press. In 1997, the state passed Resolution Number 44/97, which regulated the activities of the foreign press. In the stipulations of this resolution there was established a Center of International Press to provide oversight to foreign journalists. This resolution, composed of three chapters and 26 articles, established that no foreign press agency could contract directly with a Cuban journalist to serve as a correspondent without the permission of the state. Law 80, approved in December 1997 under the title of the "Law of Reaffirmation of National Dignity and Sovereignty," stipulates in Article 8 that no journalist may in any way, directly or indirectly, collaborate with the journalists of the enemy. The 1999 Law 88, called the "Law of Protection of National Independence and the Economy of Cuba" provides more specific limits to the rights of free expression and the press with the nation in the law's Article 7. Part of this act provides a prison term of up to 15 years to anyone that directly or indirectly provides information to the United States, its dependents or agents, in order to facilitate the objectives of the U.S. Helms-Burton Act. The law also prescribes an eight-year prison term to those who reproduce or distribute material deemed to be subversive propaganda from the U.S. government. Specifically, the law forbids collaboration "in any way with foreign radio or television stations, newspapers, magazines or other mass media with the purpose of … destabilizing the country and destroying the socialist state." Other provisions of the law create further penalties for press activities considered detrimental to the state or the communist party or beneficial to the nation's enemies.

At the passage of Law 88, the communist youth daily Juventud Rebelde ran stories that demonstrated the government's propaganda position. "Independent journalists are mercenaries: The [U.S.] Empire pays, organizes, teaches, trains, arms and camouflages them and orders them to shoot at their own people," they wrote. Castro, in public speeches, denounced the independent journalists, branding them as counterrevolutionaries. The government has long claimed that the independent journalists receive considerable funding from anti-Castro forces, especially those in the large Cuban exile community in Miami. Naturally, the independent journalists deny such charges.

Censorship

In Cuba, no law exists that either establishes or prohibits censorship. The role of censor is carried out by the Department of Revolutionary Orientation, which answers to the Ideology Secretary of the Political Bureau of the Communist Party. This department was created in the mid-1960s, first bearing the name of Commission of Revolutionary Orientation, and was charged with creating propaganda and propagating the government ideology. The department is also responsible for the design and creation of all official political communications.

Independent Press

The most pressing issue related to censorship in any study of the Cuban press is the treatment by the authorities of those who attempt to create an independent press. In the late twentieth century, as the number of these independent reporters mushroomed, the reaction of the government was forceful. The policy of official repression, which had been allowed to relax in previous years, returned powerfully in the 1990s. The government's actions included imprisonment, physical violence, and house arrest.

Only those journalists that are members of the state-controlled UPEC are allowed accreditation to practice their trade in Cuba. UPEC does not function in the manner of a press organization in a free country but instead serves as an extension of the government, assisting in their control and prior approval of the information allowed in the press. A 1997 Communist Party publication stated overtly that UPEC serves as an ideological organ of the party and that they are charged with spreading the thoughts of the revolution. Not all journalists belong to UPEC, however. In reality various independent organizations exist, though banned by the government. These groups are typically formed by dissident and opposition journalists, indisposed to undergo the control of the government. In many cases the government has removed accreditation from journalists involved with these unofficial groups.

State-Press Relations

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) has, since the early 1990s, included Fidel Castro on its annual "Ten Worst Enemies of the Press" list, a distinction that he shares with such regulars as Ayatollah Ali Khamenei of Iran, President Jiang Zemin of China and Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad of Malaysia. In 2002, the CPJ named Cuba as one of the 10 worst places in the world to be a journalist, noting that "The Cuban government is determined to crush independent journalism on the island but has not yet succeeded…." Journalists are constantly followed, harassed, intimidated, and sometimes jailed.

In early 2002, the CPJ noted with approval the recent release from prison of two journalists, but lamented the continued detention of Bernardo Arévalo Padrón, jailed since 1997. Arévalo is serving a six-year sentence imposed for "disrespecting" President Fidel Castro. The exact nature of Arévalo's offense was to refer to Castro as a "liar" when the president failed to enact democratic reforms that he had promised. Previously, the journalist had garnered ill will from the government when he made public the members of the Communist Central Committee who appropriated cattle for their own use at a time of food shortage. As of August 2002, he held the distinction as the lone journalist in the Americas behind bars for his work.

While some independent journalists find outlets in America and Europe in both Spanish and English language venues, others attempt to publish as best they can in Cuba itself. One such independent publisher, Adolfo Fernandez, creates his own quarterly newsletter with a production run of roughly 1,000 on a photocopier. He then passes these newsletters out to friends and acquaintances. Fernandez admits to withholding some criticism in his stories, preferring to moderate his tone and avoid government clampdowns. Fernandez also gets his message off of the island through radio communications and occasional offshore publication. He has taken on the role of a watchdog over the two most important government publications, Granma and Juventud Rebelde . Fernandez is typical of the independent journalists, many of whom formerly worked within the government information apparatus and who found the censorship and propaganda that rule those outlets unbearable.

The police in Cuba perpetuate violence and harassment against the independent press operatives. Their actions include constant surveillance, late-night visits, and the confiscation of the tools of their trade. Another favorite method of the revolutionary government is to make an accusation of injury or slander against the independent journalists, as in the case of Bernardo Arévalo Padrón.

The Right to Criticize Government: Theory & Practice

Reporters who work outside the state-sanctioned press system are forced to meet informally, often in the homes of individuals, to discuss ideas and utilize fax and telephone services to convey uncensored articles to editors of Spanish-language newspapers, radio and Internet news services located across Europe and the United States.

These journalists complain of abuse and persecution at the hands of the authorities. In some cases the telephone company cuts off service to homes from which these independent journalists work, and the police routinely maintain surveillance on these buildings and the reporters. Journalists report that relatives have been deprived of jobs in state-run businesses and that they are followed by the agents of the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution. Another frequent complaint is that the police routinely place these reporters under house arrest in response to events featuring the political opposition. Another tactic involves rounding up opposition reporters and driving them into remote parts of the country in order to keep them out of circulation temporarily. According to the French group Reporters sans Frontiéres, in 2001 a total of 19 of these harassed Cuban journalists chose to continue their work from exile rather than submitting to the continued persecution.

Although harassment of both low and high intensity has greeted opposition journalists throughout the years of the Castro regime, the government has not succeeded in stemming the flow of reporting from risk-taking reporters working throughout the island. Instead, the latter half of the 1990s saw an explosion in this activity. As recently as 1995, these journalists amounted to some twenty individuals working for five separate organizations. Estimates in 2002 placed the number of unofficial news agencies currently operating from within the island's shores at around twenty, representing a staff of some 100 journalists.

While some of this increase in numbers of opposition reporters might be attributed to the end of the Cold War and an increasing sense that the Castro government is nearing its twilight, it must not be ignored that the government itself, notwithstanding its continued harassment, has become more open to the idea of an independent press system. In May 2001, a group of 40 journalists banded together to effect the formation of the first independent association for journalists recognized under the Castro government. They were spearheaded by Raul Rivero, the former Moscow correspondent for Prensa Latina , the Cuban government's official news agency.

In 2001, three journalists were released from prison. Jesús Joel Díaz Hernández, the executive director of Cooperativa Avileña de Periodistas Independientes, obtained his release after serving two years of a four year sentence for "dangerousness." No explanation accompanied his release, except the warning that he could be jailed again if he returned to work as an independent journalist. Díaz Hernández, arrested on January 18, 1999, in the central province of Ciego de Avila, was sentenced the next day to a four-year prison term. The charge against Hernández was that he had six times been warned about "dangerousness." The second released journalist, Manuel Antonio González Castellanos, who served as correspondent for the independent news agency Cuba Press, obtained his release in February 2001. His October 1998 arrest had been based upon charges of insulting Castro while being detained by state security agents. The final freed reporter was José Orlando González Bridón, who had been imprisoned since December 2000 serving a two-year term for "false information" and "enemy propaganda."

González Bridón, the head of the small opposition group the Cuban Democratic Workers' Confederation, was the first opposition journalist to receive a prison sentence arising from an Internet publication. Writing since the fall of 1999 for the Miami-based Cuba Free Press, Bridón's arrest followed an August 5, 2000 article that alleged police negligence in the death of an activist killed by her ex-husband. The trial, held in a single day and not open to the public, ended with a guilty verdict and a two-year sentence, although the prosecution had only requested a one-year sentence.

Throughout the year 2001, state security agents continually harassed independent journalists and their families. In January, Antonio Femenías and Roberto Valdivia, both of whom worked for the independent news organization Patria, were detained and interrogated for three hours by state security agents after they met with two Czech nationals. The Czech representatives, accused of holding "subversive talks" and conveying "resources" to dissidents, were detained for nearly a month, a move that worsened already strained relations between Cuba and the Czech Republic.

One of Cuba's most widely known dissident journalists, Raúl Rivero, has for many years served as the unofficial leader of the nation's independent press movement. Throughout that time, Rivero has faced constant harassment from the Castro government and its security agency. Born in 1945, Rivero graduated from Havana University's School of Journalism in the early 1960s as one of the first in a group of journalists to be trained after the 1959 revolution. In 1966 he co-founded the satirical magazine Caián Barbudo and from 1973 until 1976 he served as the Moscow correspondent for the government news agency, Prensa Latina. In 1976, Rivero returned to Cuba to assume leadership of the Prensa Latina science and culture desk, a post that he held until his break with the agency in 1988. In 1989, Rivero resigned from the government's National Union of Cuban Writers and sealed his status as an opposition leader in 1991 when he became one of ten journalists, and the only one to remain in Cuba, who signed the Carta de los Intelectuales (Intellectuals' Letter), which called for the government to free all prisoners of conscience. The same year, Rivero declared official journalism to be a "fiction about a country that does not exist."

Since 1995 Rivero has headed CubaPress, one of the nation's leading independent news agencies. Viewed as a dissident for his independent work, Rivero, like all independent journalists, is prohibited from publishing on the island. His only outlets for publication are on the Internet and abroad, although in publishing internationally he runs the risk of a jail term for disseminating "enemy propaganda." He has been notified that while he is free to leave Cuba, his re-entry to the country will be denied. Rivero's celebrated February 1999 article, "Journalism Belongs to Us All," reflected on the efforts of Cuban journalists attempting to freely report the news from that nation. In this article he proclaims that no law can make him feel like a criminal for reporting the truth about his homeland. "I am merely a man who writes," he asserts. "One who writes in the country where I was born."

Attitude toward Foreign Media

The relationship between the Castro government and the foreign press has long been troubled as the government attempts to provide some access to foreign news organizations in order to serve their own ends while also attempting to effect control of the material flowing out of the country. A constant refrain in the speeches of the president is the unfair and negative tone so often evident in foreign accounts of Cuba. British journalist Pascal Fletcher, Reuter's news agency correspondent assigned to Cuba, has received especially severe attacks in the government-controlled press. In January 2001, Granma described Fletcher as being "full of venom against the Cuban revolution," while a television program aired three days later complained of the journalist's "provocative, tendentious and perfidious attitude."

President Castro, in a televised speech broadcast on January 17 and 18, 2001, complained of the foreign press and described their stance as "completely unobjective." While not mentioning any media or journalists in particular, he struck out at journalists "who dedicate themselves to defaming the revolution" or who "transmit not only lies, but gross insults against the revolution and against myself in particular." In the speech, Castro threatened to cancel the operating permits of foreign media, noting that it would be effective to remove permission to report from Cuba from an agency instead of simply deporting a single reporter.

Foreign journalists also suffer from the repressive actions of the Cuban government. In August 2000, three Swedish reporters were detained, ostensibly for immigration violations, after having conducted interviews with various independent journalists.

Foreign Propaganda & its Impact on Domestic Media

The most significant foreign broadcast presence in Cuba comes through the expense and effort of the United States government and their Radio Martí and TV Martí programs. In 1985, Ronald Reagan signed the Radio Broadcasting to Cuba Act, which established a nine-member advisory board to oversee the expansion of Voice of America services to include specifically Cuban broadcasts. The administrators of this service describe themselves as follows: "The Office of Cuba Broadcasting (OCB) was established in 1990 to oversee all programming broadcast to Cuba on the Voice of America's Radio and TV Martí. In keeping with the principles of the Voice of America Charter, both stations broadcast accurate and objective news and information on issues of interest to the people of Cuba."

Radio Martí initiated programming from studios in Washington, D.C. in May 1985. Their programming runs seven days a week and twenty-four hours a day over AM and short-wave frequencies. The broadcast schedule includes news, news analysis, and music programming. Roughly half of the Radio Martí broadcast day is composed of news-related programs. Besides traditional news coverage, the broadcasts include live interviews and discussions with experts and correspondents around the world. The station also carries live coverage of congressional hearings of import to Cuba as well as speeches by Latin American leaders. The fiscal year 1998 budget for Radio Martí was US$13.9 million. According to the OCB, Cuban arrivals in the United States indicate that Radio Martí is the most popular of Cuban radio stations, although the Cuban government goes to great expense and effort to jam the broadcasts. In 2002, in response to increasingly effective Cuban efforts to jam the Radio Martí signals, the broadcaster requested that the government of Belize allow them to use the transmitters located in that country, which were already used to broadcast Voice of America programming throughout Central America, for Cuban transmissions. The government of Belize declined this request, attempting to avoid involvement in worsening U.S.-Cuban relations. Radio Martí transmits over the air and also provides a streaming audio version of both their live programming and periodic news reports over the Internet.

Television Martí joined its radio counterpart on March 27, 1990. The programming for TV Martí originates from studios in Miami and is then transmitted to the Florida Keys via satellite. The antenna and transmitter for the station are mounted onto a balloon that is tethered 10,000 feet above Cudjoe Key, Florida. Cuban government jamming of the TV Martí signal has proven far more successful than the radio-jamming efforts, partly due to the highly directional broadcast signal used to target the broadcast into the Havana area. Because of this jamming, the signal is randomly moved to regions east and west of the capital in order to reach Cuban televisions without jamming.

News Agencies

The main internal Cuban news agency is AIN, Agencia Cubana de Noticias (Cuban News Agency). Founded in May 1974, AIN operates from Havana under the direction of Esteban Ramírez Alonso. As a key organ in the promulgation of government information, AIN predictably carries key stories that support government policies and reinforce the regime's interpretation of world affairs. For example, in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, AIN condemned the actions of Al Qaeda but spent considerably more time castigating the United States for its responses in Afghanistan and elsewhere. However, not all AIN coverage can be dismissed as propaganda. Presented in both English and Spanish, the news stories on any given day include speeches and comments by Castro and coverage of world events from a pro-government point of view, as well as less politically charged stories regarding scientific advances, cultural events, and other ordinary stories.

The Cuban government also supports and controls Prensa Latina (Latin Press), which they refer to as a Latin American Press Information Agency. While attempting to appear in the guise of an Associated Press-style news agency, the propaganda function of this service is apparent to any attentive observer. Describing themselves as the "Premier News Agency in the Republic of Cuba," Prensa Latina provides a daily news service including synthesis of materials regarding Cuba; a daily section containing the principal Cuban news stories; a Cuban economic bulletin (in Spanish and English); and a summary of vital Cuban economic, commercial, and financial news. They also publish a daily English-language "Cuba News in Brief," and the English-language "Cuba Direct," which provide translations of articles regarding Cuban news, politics, sports, culture, and art. Other occasional features include tourism news, medical news, women's issues, and coverage of Cuban and Caribbean science and medicine.

While a number of news organizations from the United States, including CNN, the Associated Press, the Chicago Tribune and the Dallas Morning News maintain permanent bureaus in Havana, foreign reporters visiting the nation are frequently harassed, threatened or even expelled.

Broadcast Media

The government maintains 5 national and 65 regional radio broadcast stations along with the international service of Radio Habana Cuba . Along with the radio services, the government supports 2 national and 11 regional television stations. The most important of these is Cubavisión , which is tightly controlled by the government. In September 2001, the government announced the establishment of a third television channel dedicated to educational and cultural programming at a cost of $3.7 million. In 1998, the nation supported 225 radio broadcast stations, 169 AM, 55 FM, and 1 short-wave. Four Internet Service Providers were in operation in 2001, although access to Internet services remained closely restricted.

A 1997 estimate set the number of radio receivers in the nation at 3.9 million, or roughly one for every three persons. The number of television sets stood at 2.6 million, or one for every four persons.

The most significant domestic television news provider in Cuba is Cubavisión Internacional. Like virtually all of the media outlets on the island, Cubavisión Internacional is controlled completely by the government.

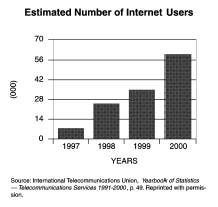

A recent addition to the services offered by Cubavisión is a streaming Internet feed, TV en Vivo, through which the current programming on the network is available internationally. Again, in view of the tiny proportion of Cubans who possess any Internet service whatsoever (roughly half of one percent in 2000), this service must be considered as an offering for those in other parts of the world and not for the inhabitants of the island. In 2002, the broadcast day on Televisión Cubana ran from 6:30 a.m. until 6:00 p.m. A 90-minute, light news program began the day. A one-hour news show and several brief news updates provided the main news coverage. Typical news coverage included political and economic coverage, stories on science, culture, society, and sports. The network also broadcast more developed special reports, some of which were considered to be propaganda pieces.

Despite the government control of the television news, the voice projected is not a completely monolithic one. One popular segment of the news is Preguntas y Respuestas (Questions and Answers) in which listeners are allowed to pose a question for the reporters to answer. The network's web site provides a feedback option as well, allowing a newsgroup-style threaded discussion of selected topics. Both of these features, while allowing a certain amount of openness, either demonstrate a lack of true dissent or are censored before they appear publicly.

CHtv represents itself as the channel of the capital, focusing its news broadcasts on the local news of Havana. CHtv has been serving Havana since 1991, and presents a two-hour-per day news program six days a week.

The other television outlet in Cuba is Telecristal , broadcasting from Holguín. The first broadcast from Telecristal was transmitted in December 1976. Along with running news broadcasts from the central government, Telecristal 's reporters provide periodic regional news and generally benign editorial comments.

Electronic News Media

Only 60,000 Cubans had access to the Internet in 2000, a figure that represented one-half of one percent of the population. At the center of the Cuban Internet presence is CubaWeb ( www.cubaweb.cu ), a large directory of government and government-controlled web sites. The main CubaWeb site appears in both Spanish and English versions and many of the subsidiary sites are available in languages beyond Spanish, suggesting that the target audience for the site is not on the island where Spanish is the primary language. Aside from links to news stories, CubaWeb provides links to media organizations, political and government entities, technology providers, cultural and arts organizations, non-governmental organizations, tourism bureaus, business groups, and health care providers.

While access to email and the Internet is not permitted to the independent press, the Cuban government maintains more than 300 websites dedicated to the press and official institutions. The government's monopolistic control of the Internet has become extreme. For more

Although the severely curtailed press freedom for non-government-affiliated media makes the printing of independent newspapers virtually impossible, the Internet has allowed an expanded voice for the independent press voices of the nation. The most prominent web-based newspaper in operation currently is La Nueva Cuba, which has been in operation since 1997. Under the guidance of Director General Alex Picarq, La Nueva Cuba provides coverage of international and national news, culture and economic events, sports, and editorials. The editorial slant of the publication, both on its opinion page and in its reporting, is decidedly anti-Castro, the content proving to be as far toward propaganda for the opposition as is the content of Granma for the government. While the web site lists addresses for correspondents in New York, Madrid, and Rome, no addresses are found referring to Havana or elsewhere on the island. In fact, on close examination, La Nueva Cuba proves far more oriented to the expatriate population of South Florida than to the inhabitants of the island. The advertisements on the site, mostly for businesses from the United States, suggest a mainland audience. Given the fact that a very small percentage of Cubans enjoy access to the Internet and that those who do are overwhelmingly affiliated with the government, the penetration of the content of this site to the population may be slight.

Education & TRAINING

Review of Education in Journalism: Degrees Granted

The leading journalism school in Cuba is the University of Havana. The typical journalism student there will earn a bachelor's degree in communication specializing in journalism. The bachelor's degree is a five-year course of study that includes a wide range of courses drawn from the sciences, social sciences, and humanities as well as more traditionally journalistic studies. The degree also requires six semesters of English. Students may elect courses in new media, photojournalism, and other specialties in addition to their required studies. After completion of a bachelor's degree, the journalism student may proceed to a master of science degree in communications, a program that begins in January of each year and generally requires two and a half years of study. Two of the three specializations offered for the master of science degree are related to journalism. Students may specialize in journalism, public relations, or communications science.

Similar undergraduate degrees are offered at most of the regional universities throughout the island. Graduate studies in journalism are available at the University of Holguín and the University of the Orient in Santiago.

In 1996, the Jose Martí International Institute of Journalism, founded in 1983 by the UPEC, resumed operations after a brief hiatus. Officially this interruption of services came as the result of "an obligatory recess brought on by the current economic difficulty in Cuba." The institute fashions itself as an "Institute of the South" and attempts to foster the continued education of Cuban journalists as well as allowing them to interact with their peers in other countries. The institute offers a variety of workshops, seminars, training programs, and other courses of a postgraduate as well as adult education nature. They also fund a selection of research projects concerning social communication on the national and international levels.

Journalistic Awards & Prizes

The highest award in journalism given in Cuba is the "José Martí National Award of Journalism." Established in 1987 by the UPEC, the Martí Award is granted in honor of a lifetime body of work. The first award was made in 1991. In 1999, in honor of the seventh UPEC Congress, 15 journalists were given the award.

In 1989, the UPEC established an award recognizing exceptional work over a year of journalism. This award is named in honor of Juan Gualberto Gómez, an exceptional nineteenth-century Cuban journalist. Each year, Gómez awards are granted in four categories: print journalism, radio, television, and graphic design.

A third award, the Félix Elmuza Distinction, is also granted to journalists, both domestic and foreign, who have earned renown through one or more of several avenues. Among the merits warranting the Elmuza Distinction are a career of 15 or more years of meritorious service, exceptional contributions to journalism, promotion of journalistic collegiality, foreign journalistic work that "reflects the reality of Cuba," or establishment of goodwill between the press and government or society.

Major Journalistic Associations & Organizations

The Unión de Periodistas de Cuba (Union of Cuban Journalists) serves as the journalists' professional organization for anyone who wishes to work in the recognized media in Cuba. Formed on July 15, 1963 from several pre-revolution organizations, UPEC is ostensibly a nongovernmental organization, although membership in this union is required for professional employment in the government-controlled media and the organization's direction is in line with government policies.

In their own documents, the UPEC states its primary obligations as the assistance of journalists in the "legal and ethical exercise of the profession," in achieving the proper access to sources, and in the general support of reporting. The organization also describes itself as being charged with "contributing to the formation of journalists in the best traditions in Cuban political thought, and in the high patriotic, ethical and democratic principles that inspire the Cuban society." The reader can see how such objectives can be read to support the government.

The UPEC code of ethics contains many statements that would seem familiar to journalists in other parts of the world. Reporters are charged with the protection of sources and with the obligation to go to multiple sources in order to ensure an accurate report. Reporters are also said to have a right to access all information of public utility. What constitutes useful information, however, is not defined. Most problematic among the ethics code provisions is Article 12, which states that "The journalist has the duty of following the editorial line and informative politics of the press organ in which he works." Since all of the press organs represented have their editorial lines prescribed by the government, this article essentially dictates that all reporters must follow the government line. The ethics code provides disciplinary sanctions for violations ranging from private admonishment to expulsion from the organization and, hence, the profession.

Summary

Conclusions

Cuban media speaks in several voices, yet this polyphony is different than in most countries. Rather than supporting an array of media outlets that span a spectrum of viewpoints, Cuba possesses a large, relatively well-funded, and monolithic state-controlled media engine paired with a small and struggling independent press. Added to these two voices are the propaganda efforts of expatriate Cubans publishing from abroad and targeting both Cuban and international audiences. Finally, the government adds an international voice as it directs a great deal of its news output toward an international audience. This cluster of voices makes a full understanding of the Cuban media more complex than it might seem on the surface.

Trends & Prospects for the Media: Outlook for the Twenty-first Century

The 1990s were a difficult period for Cuba. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Cuba lost the considerable subsidies that flowed into the nation each year. The ensuing economic hardships are only lessening 10 years after they began. Just as the first 30 years of the Cuban revolution's history cannot be separated from the Superpower relations of the Cold War, the history of the 1990s and any future events cannot be separated from Cuban relations with the United States. The continuation of the American economic boycott effectively caps the potential for Cuba's economic prosperity. Without economic dealings with the United States, it is hard to imagine the future holding a great deal of promise for Cuban journalists. Recent years have seen budgetary cutbacks expressed in reduced sizes of newspapers and a reduction in the broadcast hours of radio and television. Continued economic privation would promise more of this sort of contraction.

Just as important over the last decade has been the development of the Internet and its consequent opening of potential modes of publication for dissident journalists. As personal publishing power expands through the spread of the Internet and other media, one can expect an increase in the number and effectiveness of independent journalists in Cuba. How the government will react to such an increase, however, is not at all certain. In recent years, the Castro government has shown no interest in relaxing their stranglehold on information. While it is conceivable that the government will relax their restrictions in the face of public pressure, it is just as likely that they will redouble their efforts toward maintaining control and increase the level of harassment directed at the independent press.

Perhaps the single most important issue for the future of the Cuban media is found in Fidel Castro. After more than four decades in control of the nation, it is difficult to envision a Cuba without Castro. In the spring of 2002, former U.S. President Jimmy Carter visited Cuba and encouraged a relaxation of tensions and the policies of both nations. The Bush administration has demonstrated no interest in pursuing such a relaxation, leaving Castro isolated but in firm control.

Significant Dates

- 1990: Economic subsidies from the Soviet Union valued at US$4 to US$6 billion annually are ended, plunging Cuba into a lengthy recession.

- 1997: The government sentences Bernardo Arévalo Padrón, founder of the independent news agency Linea Sur Press, to a sentence of six years for insulting President Fidel Castro and Vice President Carols Lage.

- 1997: Resolution 44/97 is passed, establishing the Center for International Press, a government-controlled group tasked with providing oversight and direction to foreign journalists.

- 1997: Law 80, the "Law of Reaffirmation of National Dignity and Sovereignty," is passed, making journalistic collaboration with "the enemy" a criminal offense.

- 1999: Law 88, the "Law of Protection of National Independence and the Economy of Cuba," creates a wide range of penalties for journalistic activities deemed to be contrary to the benefit of the state.

- 1999: Six-year-old Elian Gonzalez is rescued after his mother's death as they, along with others, attempt to raft to the United States. A heated legal and journalistic battle rages for months before the boy is returned to his father in Cuba in April 2000.

- 2000: Three Swedish journalists are detained briefly after interviewing independent journalists.

- 2000: 3,000 Cubans seek to escape Cuba on homemade rafts and boats. The United States Coast Guard intercepts roughly 35 percent of these.

Bibliography

Anuario Estadístico de Cuba. Havana, published annually.

CubaWeb: Cuban Directory. Available from http://www.cubaweb.cu .

Elliston, Jon. Psywar on Cuba: The Declassified History of U.S. Anti-Castro Propaganda. Melbourne: Ocean Press, 1999.

Franklin, Jane. Cuba and the United States: A Chronological History. Melbourne: Ocean Press, 1997.

Latin American Network Information Center (LANIC). Available from http://info.lanic.utexas.edu/ .

Lent, John A. "Cuban Mass Media After 25 Years of Revolution". Journalism Quarterly . Columbia, SC:AEJMC, 1999.

Perez-Stable. The Cuban Revolution: Origins, Course, and Legacy. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Salwen, Michael B. Radio and Television in Cuba: The Pre-Castro Era. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press, 1994.

Mark Browning

Thanks for the paper, it has been really helpful for an essay I'm doing on Freedom of Press in Cuba. I would like to know, if possible, how I should cite this article. If you could help me with the name of the author, the date of publishing, etc., I would most appreciate it.

Thank you for your kind attention, warm regards from Ireland,

Liam

This really helped me in my essay i am proud of how far the Cuban regime of Castro has lasted but the freedom of the press is Key to the survival of any Society. Freedom of the press in Cuba would only bring a better light to Cuba and they would understand the measure at which they are effective to their people. Cuba would grow. Though since it is a Communist Country then Certain measures should be in the press but some leniency should be open... LONG LIVE FIDEL CASTRO & THE REVOLUTION.

Yours truly, your neighbor

JAMAICA