Estonia

Basic Data

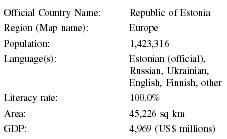

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Estonia |

| Region (Map name): | Europe |

| Population: | 1,423,316 |

| Language(s): | Estonian (official), Russian, Ukrainian, English, Finnish, other |

| Literacy rate: | 100.0% |

| Area: | 45,226 sq km |

| GDP: | 4,969 (US$ millions) |

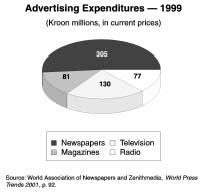

| Number of Daily Newspapers: | 13 |

| Total Circulation: | 262,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 237 |

| Number of Nondaily Newspapers: | 49 |

| Total Circulation: | 333,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 302 |

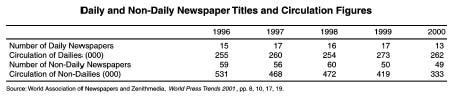

| As % of All Ad Expenditures: | 46.40 |

| Number of Television Stations: | 31 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 605,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 425.1 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 126,420 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 90.3 |

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 65,000 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 45.7 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 86 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 1,010,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 709.6 |

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 220,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 154.6 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 391,600 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 275.1 |

Background & General Characteristics

Historical Traditions

The pre-history of Estonia can be dated to 8000 BC when the oldest traces of human inhabitants were found, but the ethnic origins of the first settlers are unknown. By the third millennium BC, the settlers were Finno-Ugrians who migrated from the east, and Baltic tribes who came from the south. In the 13th century the Estonians were conquered by stronger medieval powers that were primarily German but also included the Danes, Swedes, and Russians. It was at this time that they were introduced to Christianity and the influence of western Catholicism. The composition of the indigenous peoples were basically maarahvas (country folk) while the nobility, clergy, merchants, and traders were predominantly Baltic Germans who were referred to by the local people as saks, a short form for Germans. The only way in which the local Estonian could hope to achieve a higher social status was to adopt the German language and customs and in effect, relinquish his Estonian identity.

The German Reformation movement reached Estonia in 1523 and created competition between the Lutheran and Catholic faiths. This precipitated the emergence of propagandist literature and led to the first Estonian book being published in 1525, which was destroyed because it was considered heretical. A more acceptable book, a catechism, was published in 1535, and in 1686 an Estonian edition of the New Testament was published. Education was always a key element in the national development of Estonia and peasants taught their children to read at home. As early as 1686, the first alphabet book in Estonian appeared. A complete translation of the Bible was published in 1739. Between 1802 and 1856, local people achieved emancipation and were given limited property rights. This freedom led to the development of an Estonian newspaper that was established in 1806. Between 1857 and 1861 Kalevipoeg, the national Estonian epic, was published. At that same time a new newspaper, the Perno Postimees (Parnu Mailman), was the first publication to refer to essti rahvas (Estonian people) instead of maarahvas (country folk) and became very popular among the Estonians. This stimulated the creation of additional publications and other newspapers followed such as Sakala, which was edited by Carl Robert Jakobson.

During the 19th century, the Estonian nationalist identity became stronger and by the 20th century Estonians sought independence. They achieved independence in 1918 after the First World War, known to Estonians as the War of Liberation. In 1939 Estonia was once again faced with the intrusion of a foreign power when Soviet military bases were introduced and by August 6, 1940, Estonia was annexed into the Soviet Union and forced to accept Soviet domination and influence for the next 50 years. During its occupation of Estonia, the Soviets destroyed approximately 10 to 12 million books and virtually decimated Estonian literature.

Mikhail Gorbachev, President of the USSR during the 1980s, allowed greater freedom within the various republics, a policy known as "glasnost." The Estonians took advantage of this and in 1987 launched the Popular Front, an Estonian nationalist movement. On August 20, 1991, Estonia declared itself independent from the Soviet Union and a new constitution was adopted on June 28, 1992. The final removal of Russian troops and tanks occurred in August 1994 thus terminating 50 years of Russian military presence in Estonia.

During the Soviet occupation of Estonia, journalism confronted varying degrees of censorship and the major change to occur in the Estonian media, post independence in the 1990s, was the removal of censorship. However, the evolution of this new press began as far back as 1986 when glasnost was first introduced. The Soviets began to loosen their rigid controls on the media. Periodicals began to change their style, format, and even the content of the news. Publications began emphasize the nation of Estonia and eliminate the word "Soviet." By 1989 the independent press had grown to more than 1,000 publications. These ranged from the weekly Eesti Eks press, a joint Estonian-Finnish collaboration, to smaller specialized journals that were short-lived.

Despite the growth and freedom afforded the press, there still existed serious problems. Similar to the other Baltic nations, the lack of a strong infrastructure resulted in several new dilemmas. The problems confronting the Estonian media included substance, structure, and regulation. The lack of quality control manifested itself in poor journalism. The analyses were simplistic, fact and opinion were not delineated, and chronology took precedence over significance of the stories. More important news was often lost in the calendar of events. More seriously, the failures of the editorial process resulted in deliberate misrepresentations that were used to gain political points. The former Edasi, once regarded as Estonia's best newspaper, was acquiring a reputation of deliberately twisting information and printing libelous and even plagiarized articles.

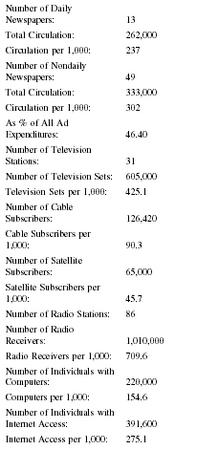

Privatization of the Estonian press proceeded slowly and in 1993 the number of publications stabilized. A major change to occur within Estonian publishing was the increasing number of foreign-language periodicals, the majority of which were in English or Swedish. In 1999 there were 105 officially registered newspapers, including 17 daily papers published in Estonia. Seventy-three of the total number and 13 of the dailies were published in the Estonian language. By the end of 1994 Estonia was considered to have the most balanced reporting of government news among the Baltic States because journalists were freer to write about political and personal issues of senior functionaries.

The media in Estonia continued to improve as indicated by a survey conducted by Freedom House that measured trends and press freedoms. Estonia improved from a rating of "partly free" in 1992 to "free" each year between 1993 and 2001.

In 1995 the major development of the Estonian press was the merger of the three largest newspapers. In 2002

The Nature of the Audience: Literacy, Affluence, Population Distribution, Language Distribution

In 2000, the population of Estonia was estimated at over 1.4 million and consisted of 65.3 percent Estonian, 28.1 percent Russian, 2.5 percent Ukrainian, and the remaining 4.1 percent other nationalities. The native Estonian is found mainly in the rural areas, whereas the non-Estonians are found in the northeastern industrial towns. Citizenship may be obtained if one is born in Estonia or at least one parent is Estonian. Naturalization requires three years of residency in the country and competency in the language. Based on the definition of literacy to mean the ability to read after the age of 15, Estonia has a 100% literacy rate.

Economic Framework

The Estonian economy grew rapidly between the two World Wars. During that time it was principally an agricultural society with some developed industry. After World War II the economy became mainly urbanized and industrialized and enjoyed one of the highest standards of living in the Soviet bloc. By the late 1980s, the serious economic and political crises that were plaguing the Soviet Union allowed Estonia to seek sovereignty from the communist rule and work towards a free and independent nation. After independence in June 1991, the Estonian government passed an ownership act that began a privatization program that transferred almost 500 state-owned companies into the private sector. In 1992 the economy began to revive after monetary reforms were instituted and the Estonian kroon was reintroduced. In late 1995 all the Estonian railways, energy, oil shale, telekon, and ports were privatized and in gas, tobacco, and air followed in 1996. These economic reforms made Estonia one of the strongest post-communist economies of the former Soviet republics. These market reforms were also the leading factors in the much needed change in the mass media sector.

In 1998, as a ripple effect of the Russian financial crisis, Estonia experienced its first economic downturn since independence. By 2000, however, the country quickly rebounded by scaling back its budget and transferring trade from the Russian markets to the European market.

Press Laws

The Estonian Constitution provides for personal freedoms, privacy, and the right to information. According to Chapter II Fundamental Rights, Liberties, and Duties, Article 44 [Right to Information]:

• Everyone shall have the right to receive information circulated for general use.

Chapter II Article 45 [Freedom of Speech]

- Everyone shall have the right to freely circulate ideas, opinions, persuasions, and other information by word, print, picture and other means. This right may be restricted by law for the purpose of protecting public order or morals, or the rights and liberties, health, honor and reputation of others. The law may likewise restrict this right for state and local government officials, for the purpose of protecting state or business secrets or confidential communication, which due to their service the officials have access to, as well as protecting the family life and privacy of other persons, and in the interests of justice.

- There shall be no censorship.

On May 19, 1994, the Law on Radio and Television Broadcasting gave the radio and television stations the right to make free decisions about their content and broadcasts and restrictions were punishable by law.

Censorship

Newspapers and periodicals have always played an important role in the life of Estonians and have survived attempts to eliminate their language, culture, and freedom of thought. The Estonian press emerged somewhat scarred after the fifty years of Soviet occupation and censorship but has worked to rectify the problems. The Constitution guarantees no censorship, but a court decision in 1997 convicted and fined a journalist on charges of offensive remarks against a politician. This decision was questioned and criticized and many felt that it was a move against freedom of speech and came very close to censorship.

In 2002 Estonia faced new complaints from the Russian-speaking population, a large group that constitutes 28.1 percent of the population. These Russian Estonians state that there is limited programming in Russian, forcing them to receive their news from Russian broadcasts. In addition, they have complained that they also face harassment from the tax authorities and other regulators because of their background.

Another ban occurred when the parliament voted in favor of banning tobacco advertising on television and radio in 1997.

State-Press Relations

The government monopoly on printing and distribution was abolished after independence was achieved in 1991 and since that time Estonia has enjoyed an independent press that is free from government interference. The major piece of legislation with which journalists are the most concerned, is the criminalization of libel. The legislature assigned the burden of proof to the media.

News Agencies

There are two news agencies in Estonia, the BNS (Baltic News Service) and ETA Interactive. The BNS is the largest and has its headquarters in Tallinn, Estonia with regional offices in Lithuania and Latvia. There are also three press organizations: the Estonian Journalists' Union; the Estonian Newspaper Association; and the Estonian Press Council.

Broadcast Media

In 2000 Estonia had thirty radio broadcasters operating and five cable channels. The major commercial stations are: Eesti Raadio (Estonian Radio); Kristlik

There are four commercial television stations in Estonia. The state-run ETV, despite receiving government funding, faced serious financial problems at the end of the 20th century that resulted in funding decreases, employee lay-offs, and programming reductions.

Electronic News Media

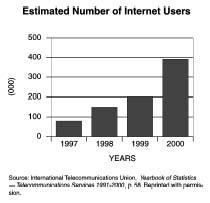

In 2000 there were 28 Internet Service Providers (ISPs) in Estonia and all major television and radio stations and newspapers had their own web sites. According to RIPE Network Coordination Center (a regional Internet registry for Europe), Estonia is one of the most Internet-connected countries in Eastern Europe. Estonia-Wide Web ( Eesti WWW-Wäark) provides a broad range of topics that are available online.

There are approximately 309,000 Internet users, 62 percent of which are male. About 89 percent of the total Internet users are between the ages of 15 and 39, with an average age of 29. The major reasons given for not using the Internet include cost and fear of computer use. However, the Soros Foundation's Open Estonia Foundation has supported many projects, including providing Internet-related services at medical, educational, and cultural institutions, to improve access to the Internet throughout the entire country.

Education & TRAINING

In 1995 the Estonian Association of Newspapers and the Estonian Association of Broadcasters established the Estonia Media College Foundation which was a move towards

Summary

The Estonian media survived censorship and subjugation by foreign powers and at the beginning of the 21st century the largest problem for the industry is economic. Since the establishment of an independent Estonia, the country has developed a growing media sector characterized by a surprisingly large number of print and broadcast outlets for the country's small population. There are a wide variety of newspapers that are privately owned and published in Estonian and Russian, private and national television channels, a state-owned public service channel, and an abundance of radio stations. The national state-owned television channel has enjoyed the highest ratings despite the competition from the independent stations. However, because of the large amount of print publications, there is fierce competition for the limited advertising and subscription revenues. Therefore, the media continues to be burdened with financial difficulties and distribution delays because debt and printing costs still plague the press.

In addition to these financial woes, sensationalism in reporting reflects the lack of law regulating media content. There is also the problem and bias against the Russian-speaking population. Despite these concerns, Estonia does enjoy an independent press. With the exception of a few legislative shortcomings, particularly regarding the criminalizing of libel, the press is generally free of government influence or control. Though the government owns the newspaper printing plant, it does not interfere with its commercial management. Overall the greatest hazard facing the press is financial loss due to limited advertising revenue.

Significant Dates

- 1997: Enno Tammer was named Estonian Journalist of the Year. He later became the first journalist to be honored and then convicted and fined for professional misconduct in the same year.

- 1998: A new Broadcasting Bill was introduced to the legislature that stipulates that at least 51 percent of television programs must be produced in the EU by the year 2003.

- 1999: In January, the Estonian broadcast media signed an agreement that would ban journalists from hosting programs for six weeks leading up to an election if they were also running for a parliamentary seat.

- 2000: The Internet TV portal TV.ee was started on December 4. In addition, Starman AS, a Tallinn-based cable television company bought a 60 percent stake in Comtrade and entered the Internet market.

- 2001: Vitali Haitov, who owned the two largest Russian language newspapers in Estonia, was killed near his home in Tallinn, in March.

Bibliography

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). The World Fact-book 2001 -Estonia. Directorate of Intelligence, 1 January 2001. Available from http://www.cia.gov/ .

"Estonia." I.P.R. Report: Monthly Bulletin of the International Press. (December-January 1996): 35-36.

"Estonia." I.P.R. Report: Monthly bulletin of the International Press 43 (December 1994): 25.

"Estonia." Nations in Transit. 2001 Available from http://www.freedomhouse.org/ .

"Estonia -Constitution." ICL. Available from http://www.uni-wuerzburg.de/law/ .

The Europa World Year Book 2001, 42nd edition, vol. 1. Europa Publications 2001, 1484-1502.

Girnius, Saulus. "The Economies of the Baltic States in 1993." RFE/RL Research Report, 3, no. 20 (20 May 1994): 1-14.

Hickey, Neil. "A Young Press Corps." Columbia Journalism Review 38 (May 1999): 18.

Hietaniemi, Tapani. "Dates from the history of Estonia." Arts & Humanities IBS. Available from http://www.ibs.ee/ibs/history .

Jarvis, Howard. "Estonia." World Press Review. 1997-2001. Available from http://freemedia.at/wpfr/ .

Kand, Villu. "Estonia: A Year of Challenges." RFE/RL Research Report 3, no. 7 (7 January 1994): 92-95.

Kionka, Riina. "Estonia: A Break with the Past." RFE/RL Research Report (3 January 1992)): 65-67.

Kionka, Riina. "Estonia." RFE/RL Research Report Vol. 1, No. 39 (2 October 1992): 62-69.

Lieven, Anatol. The Baltic Revolution: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and the Path to Independence. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999.

RFE/RL Research Institute Staff. "The Media in the Countries of the Former Soviet Union." RFE/RL Research Report 2, no. 27 (2 July 1993): 1-15.

Rose, Richard, and Maley, William. "Conflict or Compromise in the Baltic States?" RFE/RL Research Report 3, no. 28 (15 July 1994): 26-35.

Jean Boris Wynn

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: