Eritrea

Basic Data

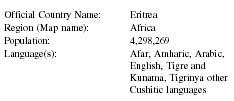

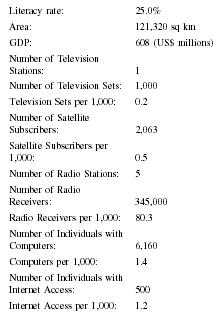

| Official Country Name: | Eritrea |

| Region (Map name): | Africa |

| Population: | 4,298,269 |

| Language(s): | Afar, Amharic, Arabic, English, Tigre and Kunama, Tigrinya other Cushitic languages |

| Literacy rate: | 25.0% |

| Area: | 121,320 sq km |

| GDP: | 608 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Television Stations: | 1 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 1,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 0.2 |

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 2,063 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 0.5 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 5 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 345,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 80.3 |

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 6,160 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 1.4 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 500 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 1.2 |

Background & General Characteristics

Eritrea is Africa's latest nation to gain its independence from Ethiopia's 40 years of occupation. After a long, drawn-out military conflict between the two states, Eritreans won their independence on May 24, 1993. Four days later, Eritrea became a member of the United Nations.

Eritrea, at 121,000 square kilometers, is a torch-shaped wedge of the physical landscape whose size equals that of Britain. The country lies along the Red Sea coast in northern Africa and borders Sudan in the north and west, Djibouti in the southeast, and Ethiopia in the south. Its coastline is 750 miles long and is intersected with the seaports of Massawa and Assab. The northern half of the country is a highland plateau on which Asmara, the capital city, is located. The country has 10 provinces (Akele, Asmara, Barka, Denkel, Gash-Senhit, Guzai, Hamasien, Sahel, Semhar, and Seraye) (Hunter 1997). The lowlands lie to the west and east while the south is predominantly characterized by aridity (Gottesman, 2001).

Demography

Eritrea's population is 4.3 million and comprises nine ethno-linguistic groups, namely Amaharic, Tigra, Kunama, Hidarb, Saho, Rosdia, Blen, Arabic and Afar. The three major languages are English, Tigrinya, and Arabic. While all the languages are used in elementary school, English forms the medium of communication in post elementary and post secondary institutions. Religiously, the country is divided into half Muslim and half Christian. About 20 percent of the people live in urban areas, and 80 percent live in the rural countryside. About 15 percent are herders and farmers and less than 5 percent practice pastoralism. About 45 percent of the total population is under 15 years, 54 percent is between 15 and 64 years (life expectancy is 56 years), and a tiny fraction is comprised of senior citizens.

The literacy rate suffers at 25 percent. A quarter of a million children are enrolled in elementary school, 90,000 attend high schools, and more than 3,000 attend post secondary institutions. Of all of these, female enrollment is 48 percent, 17 percent, and 0.3 percent as compared to males respectively. The patriarchal, traditional and religious practices tend to discriminate against women. Female discrimination is more highly pronounced in higher education, the professions, and government. Press activism intended to educate the country to bridge the gap between the sexes may be regarded with distaste.

The Press

Previously, Eritrea published both private-owned and government-sponsored newspapers. However, in September 2001 the government authorities ordered all eight newspapers in the private press closed. This included Admas , Keste Debena Mana Meqaleh Setit Tiganay, Wintan , and Zemen leaving Hadas Eritrea as the sole daily (run by the government).

State-Press Relations

Historical Background

Eritrea became independent from Ethiopian annexation rule in 1993. In 1994, Eritrea established a more concrete stand in international relations by being accepted as a member of the UN and OAU organizations. The first four years were a form of transitional or preparatory statehood. In May 1997, a new constitution was adopted but has never been ratified. The transitional government had a 4-year term and consisted of the presidency and the 130 member unicameral legislature. There is no judiciary branch. This national assembly consists of members of the only approved political party, the People's Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ). Formerly, the PFDJ was the nationalist movement that fought Ethiopia for Eritrean independence, as the Eritrean People's Liberation Front (EPLF). A marginalized opposition is centered around the Eritrean National Pact Alliance. In 1994, the PFDJ formed the Central Committee and 60 other Parliamentarians who included 11 women. The Central Committee elected the President whose constitutional responsibility is to appoint the State Council (cabinet). The transitional government had 14 cabinet ministers and 10 provincial governors. The President chairs both the State Council and the National Assembly.

In the modern world, Eritrea's historical profile, demography, political economy, constitutional and legal framework, and international relations have a profound impact in its perceptual and interpretive role of the press in an emerging democracy. These six forces form a complex interplay of factors upon which the role of Eritrean private and independent media reverberates. For instance, based on the principles of the transitional government, Eritrean government was supposed to hold general elections in September 2001. That did not happen. In a country that is perceived to be a weak but emerging democracy, the nullification of the election timetable by the government is something that makes many people skeptical, both at home and abroad. For marginalized opposition groups, an issue like this one tends to reunite, reenergize, and radicalize the opposition's challenge against the government. In the eyes of donor communities, especially the United States, whose foreign assistance to the country enables it to sustain 70 percent of its population, retaliatory diplomatic pressure on an authoritarian and "infant democratic" political system tends to overwhelm the influence of the powers that be. These corrupt powers are farther challenged by the work the print media, broadcast media, and electronic media display in public about them. This dissemination results in national and international awareness of the regime's political behavior in terms of its state-press relations.

Press Laws & Censorship

Further evidence seems to suggest that President Isayas and his single political party (PFDJ) "have unlawfully disallowed opposition parties from partaking in Eritrean politics. They also continue to eliminate challengers, muzzle discontent, imprison critics, persecute opponents, layoff civil servants and systematically exclude conscientious citizens in order to carryout the leadership's brutal and undemocratic activities" ( http://www.eritreal.org/ ). Although the Eritrean National Assembly established a commission in January 2000 for the purpose of ratifying the role and responsibility of an independent press, this constitutional and political procedure has not helped.

On February 28, 2002, ten journalists were arrested and detained indefinitely. Two unconstitutional explanations were given to justify the detention. First, since the work of some of the arrested and detained journalists is financed by foreign governments including the United States, and since the U.S. Secretary of State's office has communicated with these journalists about internal socio-economic and political conditions, there are rumors of governmental fears of exposure. Media coverage and powerful communication technology in the arena of political corruption and diplomatic pressure tend to expose sensitive bureaucratic issues which may serve to discredit democratic political rationality in Eritrea (Robinson, 2000). Second, some of those who were arrested, as the government claimed, failed to complete their mandatory military service. Journalistic detainees are members of the private press whose freedom to write, publish, educate, and communicate is in the national constitution. Irrespective of their constitutional privileges and immunities, the Eritrean Press Corps was "silenced." Meanwhile, the pressmen had been on a two-month hunger strike that incapacitated one of them, a statement that was made public on April 10, 2002.

Since the laws holding the pressmen in prison are supposed to be interpreted in the context of legal jurisprudence, their interpretation remains to be challenged since the nation lacks a judicial system and since that lack is partially rooted in its ethnic and political controversies whose dynamics dictate and reinforce it.

Eritrean laws say that a detained suspect has the right to be free on bail, pending investigation, unless the suspect is a flight risk, a threat to his community or will tamper with evidence. Accordingly, the Eritrean public forum and the organization of the African commission on Human and Peoples' Rights urged the Eritrean government to consider enforcing the right to the bail of the detainees under a scheme where the movements and activities of the suspects on bail are legitimately limited in place and time, with full supervision that ensures that these suspects do not violate the terms of their bail. Freeing the journalists on bail will be necessary if the Eritrean government requires more time to complete its case against them. Such violation is inconsistent with the freedom of the press in its emblematic significance that challenges print, broadcast and electronic journalism.

Broadcast & ELECTRONIC News Media

Eritrea claims only one television station and three radio stations, all of which are government-controlled as private ownership is prohibited. As of a 1997 estimate, only 345,000 Eritrean households had radios and a scant 1,000 possessed televisions.

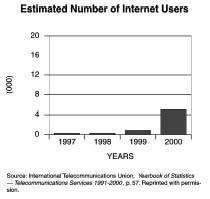

Furthermore, in the year 2000, Eritrea had the distinction of being the last country in Africa to provide Internet access to its people. With only four Internet Service Providers and a mere 500 users in 1999 (who pay relatively high usage fees) electronic media is clearly in its infancy without much foreseeable growth.

Summary

In Africa, the role, constraint, and concern of the press, as the continent struggles with democratization and other development issues, is no exception to the challenges of the Eritrean private press. The press' role in and contribution to democratic political governance and bureaucratic accountability is viewed with skepticism and distaste for its controversial stance and imperialistic overtones.

By using psychological and diverse ways of understanding and influencing the public, the press can effectively play its role as an investigator, reporter, and agenda-setter. This role is that of being a carrier because the press tends to creatively formulate and articulate agenda for public policy debates. The courage, skill, and dynamism with which the press carries out its responsibility in the Third World, in the midst of surmounting obstacles, could be different from that of its counterpart in well-established and constitutionally more tolerant democracies. Therefore, Western-oriented, ideologically intoxicated, and democratically minded private press may find it difficult if not impossible to professionally survive in Africa and particularly in Eritrea. To function well in such an environment, the press may need to learn how to adapt itself to new and challenging situations in order to capitalize on existing opportunities.

Bibliography

Absuutari, Pertti. ed. Rethinking the Media Audience: The New Agenda . London: Sage, 1999.

AllAfrica.com . "National Assembly Endorses Press Clampdown, Sticks to One-Party System." AllAfrica Global Media, August 2002. Available at http://www.allafrica.com .

—— "Government Admits to CPJ that it is Holding Journalists in Secret Detention." AllAfrica Global Media, August 2002. Available at http://www.allafrica.com .

Amnesty International. "Eritrea: Growing Repression of Government Critics." Amnesty International Report 2002. London: Amnesty International, August 2002. Available at http://web.amnesty.org .

Awde, Nicholas and Hill, Fred James, eds. Nations of the World: A Political, Economic and Business Handbook .Millerton, NY: Grey House Publishing, 2002.

Barnett, Clive. "The Limits of Media Democratization in South Africa: Politics, Privatization and Regulation." Media Culture and Society , 21, 5, 649-672, 1999.

Burstien, Paul. "Bringing the Public Back" In: Should Sociologists Consider the Impact of Public Opinion on Public Policy . Social Forces, 77, 1, 27-62, 1998.

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). "Eritrea." The World Factbook . Directorate of Intelligence, August 2002. Available from http://www.cia.gov .

Committee to Protect Journalists. "Eritrea: Nine journalists arrested; two others flee as crackdown continues." CPJ: 2001 News Alert . New York, NY: CPJ, 2002. Available at http://www.cpj.org .

Dayan, Daniel. "The Peculiar Public of Television." Media Culture and Society , 23, 6, 743-765, 2001.

Diamond, Larry. Developing Democracy: Toward Consolidation . Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999.

Decalo, Samuel. The Stale Ministry: Civilian Rule in Africa, 1960-1990 . Gainsville, FL: Academic Press, 1998.

Freedom House. "Eritrea." Freedom in the World . Freedom House, Inc., August 2002. Available at http://www.freedomhouse.org .

Gaubatz, Kurt Taylor. Elections and War: The Electoral Incentive in the Democratic Politics of War and Peace .Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1999.

Gottesman, Leslie, D. "Eritrea." World Education Encyclopedia: A Survey of Educational Systems Worldwide .1, 410-419, Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group, 2001.

Gunther, Richard and Mughan, Anthony. eds. Democracy and the Media: A Comparative Perspective . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Human Rights Watch. "Eritrea." Human Rights Watch World Report 2002 . New York: Human Rights Watch, August 2002. Available at http://www.hrw.org .

Hunter, Julian. ed. The Stateman's Yearbook: A statistical, Political and Economic Account of the States of the World . New York: St. Martin's Press, 1996-1997.

Linz, Juan, J. and Stepan, Alfred. Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation: Southern Europe, South America, and Post-Communist Europe . Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

Mickiewicz, Ellen. ed. Changing Channels: Television and the Struggle for Power in Russia . Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999.

Milton, Andrew, K. The Rational Politician: Exploiting the Media in New Democracies . Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2000.

Mughan, Anthony. Media and the Presidentialization of Parliamentary Elections . New York: Palgrave, 2000.

Munck, Gerardo, L. "The Regime Question: Theory Building in Democracy Studies." World Politics: A Quarterly Journal of International Relations , 54, 1, 119-149, 2001.

Norris, Pippa. ed. Women, Media, and Politics . New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Patterson, Thomas, E. We the People: A Concise Introduction to American Politics . Boston: McGraw, 2002.

Robinson, Piers. "World Politics and Media Power: of Research Design." Media Culture and Society , 22, 2, 227-232, 2000.

Tettey, Wisdon, J. "The Media and Democratization in Africa: Contributions, Constraints and Concerns of the Private Press." Media Culture and Society , 23, 1, 5-31, 2001.

Volkomer, Water E. American Government . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2001.

Meshack M. Sagini

But in Ethiopia Media show your activities & country not about other.

We fade up for Eritea Media very much. You do not have another essue. Make of your country the best, not deserve another people & country, we in the region like peace, but Eritrean Media deserve this peace in the region.

Previously, Eritrea published both private-owned and government-sponsored newspapers. However, in September 2001 the government authorities ordered all eight newspapers in the private press closed. This included Admas , Keste Debena Mana Meqaleh Setit Tiganay, Wintan , and Zemen leaving Hadas Eritrea as the sole daily (run by the government).its unlawful and illegal activity against media and free speech and free will of the state and people of Eritrea.so just lets take a step forward and abuse against the peope who are opposite the free media and free press.