Georgia

Basic Data

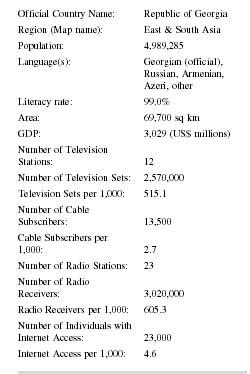

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Georgia |

| Region (Map name): | East & South Asia |

| Population: | 4,989,285 |

| Language(s): | Georgian (official), Russian, Armenian, Azeri, other |

| Literacy rate: | 99.0% |

| Area: | 69,700 sq km |

| GDP: | 3,029 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Television Stations: | 12 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 2,570,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 515.1 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 13,500 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 2.7 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 23 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 3,020,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 605.3 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 23,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 4.6 |

Background & General Characteristics

Georgia is situated at a crossroads between Europe and Asia. The country borders on Turkey, Russia, Armenia and Azerbaijan. It covers 26,911 square miles (about the size of Ireland) and has a population of nearly 5.5 million. The country includes two autonomous republics— Abkhazia and Ajara, as well as the autonomous region of south Ossetia. Abkhazia and the Tskhinvali region (South Ossetia) do not recognize Georgia's jurisdiction, even though no international organization recognizes the territories' independence.

Georgian history dates back more than 2,500 years, and Georgian is one of the oldest living languages in the world with its own internationally recognized alphabet, one of only thirteen recognized alphabets in the world. Although Russian is still universally spoken (except in the case of the very young), street names and most of the local press is in Georgian. Tbilisi, located in a picturesque valley divided by the Mtkvari River, is more than 1,500 years old. Much of Georgia's territory has been besieged by its Persian, Turkish and Russian neighbors along with Arabs and Mongols over the course of the seventh to the eighteenth centuries. After 11 centuries of mixed fortunes of various Georgian kingdoms, including a golden age from the eleventh to twelfth centuries, Georgia turned to Russia for protection. Russia annexed Georgia in 1801, but the first Republic of Georgia was established on May 26, 1918 after the collapse of Tsarist Russia. By March 1921, the Red army had reoccupied the country and Georgia became part of the Soviet Union. On April 9, 1991, the Supreme Council of the Republic of Georgia declared independence from the USSR.

Historically Georgia has always been a multinational country, serving as the crossroads of major trade links. Competition for such a strategic geopolitical location has been consistent. There are representatives of about 100 nationalities in Georgia. Armenians with a population of 437,211—8 percent of Georgian population—is one of the largest ethnic minorities in Georgia. Turkish-speaking Azerians, 307,556—6 percent of Georgian population—inhabit the regions of Rustavi and Azerbaijan are Shiite Moslems. Russians 341,172—6 percent of Georgian population—have no region of concentration. Today many Russians are migrating back to Moscow and the central regions of Russia. Ossetians—156,055 (3 percent), have settled in the Ossetian Autonomy Region, Gori, Khashuri, and Borjomi regions. According to the Georgian Constitution, Georgian and Abkhazians consist of North-Caucasian people related to the Adigean tribes and number 95,853—2 percent of the Georgian population. They are groups including Greeks—100,324, 2 percent; Jews, 24,795; and Kurds. At present, there are large numbers of Georgian refugees from Abkhazia living in Tbilisi with government support. These 230,000 internally displaced persons present an enormous strain on the economy. Peace in the separatist areas of Abkhazia and south Ossetia, overseen by Russian peacekeepers and international organizations, continues to be fragile, and will probably require years of economic development and negotiation.

Although Georgia has a long and close relationship with Russia, it is reaching out to its other neighbors and looking to the West in search of alternatives and opportunities. It signed a partnership and cooperation agreement with the European Union (EU), participates in the Partnership for Peace, and encourages foreign investment. France, Germany, and the U.K. all have embassies in Tbilisi, and Germany is a significant donor. There are large numbers of United States citizens and organizations contributing tens of millions of dollars per year.

History of the Press

An excellent history of the press in Georgia was published in 1997 by the Caucasian Institute for Peace, Democracy and Development (CIPDD) with the support of the United Nations Development Program (UNDP). The first Georgian newspaper, Sakartvelos Gazeti , was published in 1819. By 1897 the average daily circulation of Georgian publications reached 3,000, the same figure as that estimated today although the population and literacy rates have both increased substantially. In soviet days, publications were run by the Communist Party and were produced on typewriters and photocopiers. In 1981, 141 newspapers were published: 12 national, 7 regional, 9 town, 66 district and 47 village, for a total circulation of 4.04 million copies.

It should be noted that during Communist rule the highest circulation was the Comunisti newspaper, at 700,000 copies a day. Soplis Tshkovreba (Rural Life) followed with 240,000, then Tbilisi at 145,000, Zaria Vostoka (The Dawn of the Orient) at 140,000, the Armenian language Sovetakan Vrastan (Soviet Georgia) at 33,000, and the Azerbaijani Sovetan Gurjistani (Soviet Georgia) at 35,000. The Lelo sports newspaper had a circulation of 120,000 while Akhalgazrda Comunisti (Young Communists) published 240,000 copies three days a week.

The first offset newspaper was Tavisupleba (Liberty) , published illegally in 1989 by the National Independence Party. The second issue was seized in the printing house by the KGB. When President Gamsakhurdia was replaced by Eduard Schvernadze in 1992, press restrictions eased although active suppression of the Gamsakhurdia press did not cease until 1994. Following soviet and European models, most early post-perestroika newspapers were organs of political parties. The first non-party paper, 7 Dghe (7 Days) was founded in 1990, sponsored by the Journalists' Association. Only now is an independent comprehensive press beginning to emerge. Of the thirty-six registered party publications, only ten still publish.

The Press

As in many changing societies, definite numerical information is difficult to come by in Georgia, in large part because all of society and the press in particular is in a state of flux.

The Georgian press is probably the most free press of all the nations of the former Soviet Union. The Georgian Parliament has enacted the strongest Freedom of Information Law in the former Soviet states which is stronger even than the U.S. Freedom of Information Act. Further, Georgian journalists have learned what the law means and how to go into court to use this law. By mid 2002 three court cases under this provision of the Administrative Code have been taken to court and three decisions have been obtained in journalists' favor. Further, the government of Georgia, although exerting pressure from time to time, is relatively tolerant of a free press. For example, Rustavi 2, the independent television station which is trying to build a quality media organization, has regularly run a nightly cartoon lampooning President Schvernadze, apparently with impunity.

Government pressure tends to come through selective enforcement of complex and ever changing administrative and tax code provisions. Otherwise, the complex regulatory provisions are seldom enforced.

Infrastructure of the Media

Although a subscription system does function, it plays only a small role. Distribution of periodicals is only in Tbilisi and Kutaisi. The biggest heirs of the former Soyuzpechat are Matsne and Sakpresa , the former serving Tbilisi and the latter supplying the regions. Their service is so ineffective, however, that independent publications do not use either of them. Soyuzpechat was transformed into a joint stock company in 1993, but newspapers were discouraged from buying shared by the Ministry of Communication. This led Alia , Rezonansi , Akhali Tacoba and 7 Dghe to found the Association of Free Press in 1995, which fostered professional solidarity and created a network of newsstands to bypass the distribution bottleneck. The new but already popular Dilis Gazeta (Morning Paper) established its own system of regional distribution using automobiles, which allows it to make speedy deliveries across the country. For instance, a car which heads for Batumi at 5 a.m. reaches the destination by 1 p.m. As a result, Dilis Gazeta is the only Tbilisi paper read in Batumi on the same day.

TV and radio stations use their own reporters to cover local stories and news agencies to cover stories affecting larger areas. There is little information appearing about the provinces.

The size of a newspaper's staff generally ranges from twenty-five to thirty, including technical personnel. The professional level of journalists is not satisfactory.

Many papers have their own computers at their disposal, but usually they do not have enough, and the ones they have are not the most up-to-date models. Machines fit for computer graphics are in especially short supply. Furthermore, most newspaper journalists themselves do not have access to computers, and thus are not experienced in their use.

Economic Framework

Georgia's economic recovery has been hampered by the separatist disputes in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, a persistently weak economic infrastructure, and resistance to reform on the part of some corrupt and reactionary factions. However, the government has qualified for economic structural adjustment facility credit status, introducing a stable national currency (the lari), preparing for the second stage of accession to the World Trade Organization (the first stage has already been met), signing agreements that allow for development of a pipeline to transport Caspian oil across Georgia to the Black Sea, and passing laws on commercial banking, land, and tax reform. However, Georgia has been unable to meet International Monetary Fund (IMF) conditions recently and the new laws have yet to be implemented.

Inflation, however, ran to 300 percent in 1997, a phenomenon that steadily decreased to the 25 percent inflation rate in 1999. Tax revenues have risen somewhat, and recent tax reform encouraged by the IMF, should lead to further increases. However, Georgia needs to implement its tax legislation and take concrete steps to meet IMF programs. Although total revenue increased from 1996 to 1997, these increases were lower than expected. International financial institutions continue to play a critical role in Georgia's budgetary calculations. Multilateral and bilateral grants and loans totaled 116.4 million lari in 1997 and are expected to total 182.8 million lari in 1998 (lari were about two to the dollar).

The government says there has been some progress on structural reform. All prices and most trade have been liberalized, legal-framework reform is on schedule, and massive government downsizing is underway. More than 10,500 small enterprises have been privatized, and privatization of medium and large firms has been slow.

Georgia's transportation and communication infrastructure remains in very poor condition. Parliament has set an agenda to start the privatization of the telecommunications industry, although there is still resistance to the plan. Georgia's electrical energy sector continues to have great difficulties.

Described by the international financial press as the most corrupt country in a corrupt region, Georgia needs a stable and uncorrupt legal and financial system if it is to achieve economic progress. The IMF estimates that 70 percent of the Georgian economy is in the "shadow" or extralegal economy.

Press Economics

A major problem for the Georgian press is that hardly any Georgians understand the business side of the newspaper business and few Georgian businesses can see the need to advertise especially in the countryside where businessmen tend to feel that everyone already knows what they do, and that advertising may just attract the unwelcome attentions of the tax authorities. The lack of financial stability leads sometimes to sloppy sensationalism in reporting in an attempt to expand circulation. It has also lead to hidden financial support by influential members of society such as government officials, members of prominent families and provincial government officials. These sponsorships are fairly obvious to the sophisticated reader as the sponsors' requirements are that the publication being supported defend the sponsor and attack his/her enemies; so, the positions taken by the paper make the sponsorship apparent.

At present, the Georgian press is in flux with news organizations forming and reforming for political, philosophical, financial and policy reasons. Thus, an excellent circulation survey done in 2001 is no longer valid in 2002 because many of the publications surveyed in 2001 no longer exist in 2002.

The quality of news reporting is poor, both because most newspapers pay so poorly that journalists must have additional jobs to survive financially, and because so few journalists have any professional training or experience. The excellent Journalism School sponsored by the International Center for Journalism out of Washington, D.C., is helping to change this situation. An attempt to establish a high quality newspaper called " 24 Hours " is being undertaken by the television station Rustavi 2, and this effort includes the payment of higher salaries to the journalists involved.

Press Laws

The Georgian Constitution and the 1991 Press Law guarantee freedom of speech and the press. At present, the Law on Press and Other Media, adopted in August of 1991 and based on the analogous Soviet law, is still in effect. The Law is acknowledged by journalists to be exemplary, but there exists no official independent watch-dog body authorized to monitor its implementation and review, alleged violations and charges of non-compliance. Most journalists consider the duality of some articles of the law its main shortcoming. The Law states "the press and other mass media in the Republic of Georgia are Free". The principal of freedom of the mass media is similarly written into the Georgian Constitution adopted in August, 1995. This states, specifically, that "the mass media are free; censorship is impermissible" (Article 24.2) and that "the state or separate individuals do not have the right to monopolize the mass media or the means of disseminating information" (Article 24.3). Citizens of the Republic of Georgia have the right to express, distribute, and defend their opinions via any media, and to receive information on questions of social and state life. Censorship of the press and other media is not permitted.

Restrictions on the free flow of information via the media are enumerated in Article 4 of the law, which stipulated that "The mass media are forbidden to disclose state secrets; to call for the overthrow or change of the existing state and social system; to propagate war, cruelty, racial, national or religious intolerance; to publish information that could contribute to the committing of crimes; to interfere with the private lives of citizens or to infringe on their honor and dignity." Article 21 of the law established the rights of journalists to gather information. At the same time, the law made clear the subordination to, and responsibilities of, the state controlled media vis-a-vis the government. Article 18 stipulates that government controlled media outlets are obliged to do so only in "exceptional circumstances," such as the outbreak of war or natural disasters.

Despite the introduction of amendments and additions, the Law on Press is almost never applied in law enforcement practice. In Georgia, the Law on State Secrets, which determines the types of information that are not freely accessible due to the necessity of protecting the state security, is in force. The Law on State Secrets, adopted by parliament in September 1996, demands that the Council on National Security develop criteria of secret information to be approved by the president.

The Law on Press and Other Mass Media states that, "activities of a mass media outlet may be banned or suspended if it repeatedly violates the law thus contributing to crime, endangering national security, territorial integrity, or public order."

Censorship

During the early rule of ultra-nationalist Zvia Gamsakhurdia, political debate flourished in the pages of the Georgian press. However, as of early 1991, media freedom was systematically eroded. In October 1991, a group of TV journalists was dismissed and the majority of the personnel went on strike. Between December 1991 and January 1992, armed supporters of the regime detained several TV journalists and kept them in the basement of the presidential residence. They were freed after Gamsakhurdia's flight.

The situation altered after Eduard Shevardnadze's return to Georgia, although not immediately. While representatives of moderate opposition parties had greater access to the governmental media, certain high-ranking officials were irritated by the pro-Zviadist, as they stated it, orientation of several outlets. Independent journalists were subjected to systematic harassment and opposition newspapers were closed on the flimsiest of pretexts. However, in the case of, for instance, Iberia-Spectri , Eduard Shevardnadze intervened personally and ensured that publication of the paper was allowed. In 1994, a gradual relaxation of political control of the press got underway and in November 1995, several journalists confirmed that the media enjoyed greater freedom than one year earlier.

In 1996, the Independent Federation of Georgian Journalists recorded no obvious violations of the freedom of the speech. In one case, an article contradicted the criminal code. The newspaper Noy was closed down following the publication of anti-Semitic material. The editor (responsible for the piece) was charged with "inducing hostilities between nations" by the Office for Public Prosecution. The rather monopolistic position of the Information and Publishing Corporation Sakinform has also raised some concern, in particular regarding the provision of information. According to one observer, the "tame media always appear to be the first to receive information."

The law and the Constitution cannot always safeguard the protection of media outlets, as is illustrated by the Rustavi 2 case.

The agency Gamma Plus registered with the Ministry of Justice in 1994. The regulations of the agency envisaged the right for broadcasting and on these grounds a license allowing exploitation of the 11m-television channel was given by the Ministry of Communications. The TV channel adopted the name Rustavi 2 and soon became very popular both in Rustavi (located about 21.75 miles from Tbilisi) and in the capital. However, only several months after it went on the air, Rustavi 2 transmission was stopped. The Rustavi municipality applied to the Ministry of Communications, demanding to deprive Rustavi 2 of its right for broadcasting and to transfer its channels to an independent telecompany, Kldekari, that was set up by the municipality itself. The Ministry of Communications annulled its decision and blamed the Ministry of Justice for leading them astray. The latter also altered their position and the broadcasting of Rustavi 2 resumed. However, in July 1996 the Ministry of Communication reconsidered its verdict and once again deprived Rustavi 2 of its license on the same grounds ("invalid"). A rival company was granted permission to broadcast on the available frequency. This time, the management of Rustavi 2 decided to launch a court appeal and ultimately prevailed.

In 1992, the country's new administrative code was approved. A significant portion of the code deals with the regulation of access to information.

Religious Censorship

The Georgian Orthodox Church is especially aggressive in hindering the spread of information regarding religious problems, corruption in its staff, or violations of the constitutional principle of separation of church from the school system. The church also does not want other sects or religions to receive any type of publicity. The media acquiesces in this matter, and covering of other churches is nonexistent or superficial. For example, in 1993 when an article was published on the growth of fundamentalism, the secretary of the Patriarch threatened the authors and editorial board of the paper with excommunication, along with a pair of TV announcers who had mentioned the article in their newscasts.

In 1997, an aggressive campaign against a history of religion textbook authored by Nugzar Papuashvili was carried out. Orthodox fundamentalists staged a public burning of that and other books they considered offensive. Representatives of the church said the reporting on the book burning fanned anticlerical hysteria.

State-Press Relations

The Ministry of Justice registers media outlets, while the Ministry of Communications grants (or revokes) licenses for broadcasters, manages the state printing house, the distribution of newspapers and the "subsidies" to state-owned media. The Ministry for Press and Information is, besides providing official information, responsible for the accreditation of journalists. The ministers are appointed by the president and the parliament or its president do not, de jure , have direct influence. The only exception is the appointment of the chairpersons of the State TV and Radio Corporation and the official Information and Publishing Corporation Sakinform, who should be approved by parliament. In addition, the parliamentary subcommittee on mass media drafts laws that concern mass media and reviews laws drafted by other bodies in view of their correlation with the current legislation on mass media.

The 1991 press law requires that journalists "respect the dignity and honor" of the president and that they do not undermine the state. The law provides penalties for publications that convey "false information" or "malevolently use the freedom of the press." There are state-owned as well as private television and radio stations. Many independent newspapers reflect different political views and suffer from varying degrees of harassment. State-owned newspapers follow the government line. While media became more independent of government control, they are not editorially independent of financial supporters.

Currently, there is a pervasive tendency toward self-censorship by Georgian editors. Journalists in state-run media fear offending government officials, while their independent counterparts worry about insulting other influential structures in society. This tendency is generally more visible among older journalists and is a residue of the Soviet era.

In June 2000, Georgian authorities tried to force "rebel" broadcast journalist Akaki Gogichaisvili out of the country, Gogichaisvili, anchor of the popular Rustavi-2 television show, "60 Minutes," had been under constant attacks from the prosecutor's office. Vasil Silagadze, a reporter for the Eco Digest daily newspaper in Georgia, was attacked in July 2000 by local police officers after publishing an article detailing police corruption. His attackers slashed fingers on his right hand so he "wouldn't be able to write for a while," and threatened further retAliation if he continued his investigations.

More recently, the murder of popular television anchor Giori Sanaia has triggered charges that he was assassinated in retAliation for his pursuit of government corruption on the Rustavi 2-channel talk show. The 26-year-old anchorman of Georgia's "Night Courier" program was shot dead in his apartment with a single bullet to the back on July 26, 2001. The assassination precipitated national mourning. Facing public suspicion about the role of the security ministries, the government swiftly invited the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation to give forensic assistance to the investigation. The police quickly arrested a man previously detained on a fraud charge, yet at this writing prosecutors had not presented sufficient evidence to indict him for Sanaia's murder. Some commentators linked Sanaia's shooting, which appeared to be expertly planned and executed, to purported knowledge or video material he had obtained, allegedly demonstrating links between law enforcement officials with criminals in Georgia's Pankisi Gorge who engaged in kidnappings and the narcotics trade.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

The U.S. Department describes Georgia's foreign relations as "excellent" and makes no remarks concerning danger to foreign journalists in Georgia while detailing its need to create opportunities for development through international and non-governmental organization (NGO) contacts. No incidents concerning the mistreatment of foreign correspondents have been noted.

Georgian media have few if any foreign correspondents and rely on contacts with news organizations in Azerbaijan, Arania and Russia. Many papers subscribe to news agencies, but basic sources are internet and foreign broadcasts.

Broadcast Media

Television

The first unsuccessful attempt at independent television came when a group of staff left the State Radio-TV Company in 1990 to start their own venture. After several months of pressure from the authorities, the private TV station Mermisi (Future) was closed. The next major event was the establishment of (state-owned) Channel 2 in 1992.

Ibervisia, which joined the scene in 1992, also played an important but short-lived role in the development of independent television. Ibervisia was a joint venture of the former Komsomol leaders and the so-called Borotebi (Evils), a branch of the paramilitary Mkhedrioni organization. The controversial images of the partners paralyzed the work of the channel, which was finally closed after the weakening of the Mkhedrioni's political influence.

According to CIDD altogether 40 TV stations, including municipal channels, broadcast in Georgia today. The professional skill of their staff, together with the quality of programs, is low. Such types of stations were founded mostly by self-taught enthusiasts, who even constructed the transmission devices themselves. A primitive montage set made out of two VHS recorders is regarded as a great achievement, almost a luxury.

The Georgian television network (TNG) started its work in 1996, bringing together 15 stations not owned by the state that covered 15 cities and towns. Eighty percent of the TNG members' broadcast time consists of licensed video productions. The purchase of these programs is the main goal of the network.

In May 1996, the independent television stations started broadcasting a joint weekly program, exchanging materials with the US Internews Network. The "Kvira" (Week) program still presents the sole attempt at reviewing the events of the whole country.

Broadcast media continues to be the main source of information for the vast majority of Georgia's population. Television sets number around 2,570,000, while there are approximately 3 million radio receivers in the country. Over the past two years, however, there has been growing competition from independent TV companies, forcing state TV to make its programming more objective and balanced, yet it remains far from editorially independent.

The government's monopoly on television news was broken when Rustavi-2, a member of the independent television network TNG, emerged in 1998 as an important alternative to state television, after successfully resisting two years of government attempts to shut it down. It is now considered the only station other than the state-run channel with a national audience. In addition to Rustavi-2, there are seven independent television stations in Tbilisi. An international NGO that works with the press estimated that there are more than forty-five regional television stations, seventeen of which offer daily news. While these stations are ostensibly independent, a lack of advertising revenue often forces them to depend on local government officials for support. Some regions, such as Samtskhe-Javakheti and Kutaisi, have relatively independent media. Rustavi-2 has a network of fifteen stations, five of which broadcast Rustavi-2's evening news program daily. Independent newspapers and television stations continue to be harassed by state tax authorities. Stations desiring benefits and better working relations with authorities, practice self-censorship.

Since Rustavi-2, the first powerful independent TV station, survived government attempts to close it down in 1997, viewers in Tbilisi have enjoyed a much greater choice of available programming. Rustavi-2 currently attracts higher ratings than official TV and, according to 2001 data, carries about 55 to 65 percent of the national advertising market. Seven other independent TV stations compete for the TV market in the capital, but unless they receive support from powerful business or political interests, they suffer from severe financial problems. Iberia TV, supported by the Batumi-based Omega, cigarette distribution network, and Skartvelos Khma are seen to represent the views of Asian Abash, an Ajarian regional leader. Stations outside of Tbilisi struggle to maintain their independence as they continue to suffer financially. In January 2000, a 10-member United Television Network (UTN) was created to pool-advertising revenues from small regional stations.

Channel 25 is the only independent television station broadcasting in Ajara, and has been operating since 1998. On February 14, 2000, it broadcast its first uncensored news coverage. On February 19, three of the four owners of the station alleged that they were coerced by Ajaran regional government officials and Mikhail Gagoshidze, chairman of Ajaran Television and Radio, to cede 75 percent of the company's shares to Gagoshidze. The owners stated that in return they were forced to take $50,000 (100,000 laris) in cash. The same day, Batumi mayor Aslan Smirba physically assaulted Avtandil Gvas Alia, the station's commercial director. Smirba claimed that he had a right to own the station, as he had helped the company get permission to broadcast. The owners brought suit against Gagoshidze, but lost their case in Ajara regional court.

Another formidable obstacle for the Georgian media industry is the registration and licensing requirements detailed in Article 7 of the Media Law. Article 10 of that law authorizes the state of deny registration to a media outlet whose goals are considered contradictory to Georgian law.

The lack of legal definition regarding the activity of media and journalists is leading to an increase in the use of force. Georgia has many cases of violence against media professionals. One example is the case of the beating of a correspondent for the newspaper Eco Digest , Vasily Silagadze. On July 25, an unknown group of people approached him on the street, identified themselves as policemen, took the journalist to a park and beat him up, advising that he "write less about the police." The journalist

Radio

Radio listenership varies. The Soviets did not use radio widely and a consistent listenership was not established, but many Georgians had formed the habit of listening to the Voice of America and Radio Liberty and these habits persist despite the technical difficulties in the mountainous regions. Reports differ as to whether Georgians, especially in Tbilisi, rely more on the press or TV for daily news. The Rustavi 2 nightly news program appears to reach many people.

A number of independent radio stations broadcast on AM and FM frequencies, but most of their programming consists of music. State radio continues to dominate the regions outside Tbilisi. Radio Fortuna, a privately owned, 24-hour FM station that covers the entire area of Georgia, has the largest audience with more than 620,000 listeners while the combined audience of the two Georgia state radio stations number at 580,000.

In Tbilisi the FM waves are used by one state-owned radio station and six private ones. Most stations play music and are paying less and less attention to the news. Some stations rebroadcast news in Georgian from Voice of America and Radio Liberty. One of the stations, Audientsia, broadcasts in Russian. Private FM stations operate in Kutaisi, Zugdidi, Samtredia and Batumi (although the latter actually appears to be owned by the local ruling party). Most of the FM broadcasters provide only superficial news coverage, as they find other ways to compete for the attention of teenagers, the basic listeners of private radio stations.

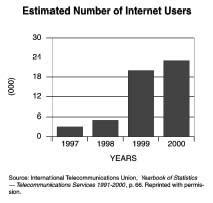

Electronic News Media

Only a small fraction of the Georgian population has access to the Internet. Experts estimate that the country has between 10,000 and 12,000 Internet users in a population of 5.4 million. Although this represents a significantly low percentage of the people, there has been an increase of 3,000 users since 1999.

Competition among Internet service providers is extremely high, with Sanet, ICN, and the new Georgian Online, owned by Rustavi-2, dominating the market. Some Georgian newspapers and news agencies have also launched on-line editions. Among the more popular: The Georgian Times ; Svobodnaya Gruziya (Liberated Georgia), Agency Starke Information; Prime-News; The 1st channel of Georgian TV; and Virtual Georgia.

Education & TRAINING

Academic freedom is respected in Georgia and outside support has contributed to limited improvements in Georgian media. The largest western foundations, such as United States Information Agency (now a part of the State Department), Eurasia Foundation, and TACIS have been working in the country to improve the quality of journalism. They organize various workshops, training course seminars and conferences for local media professionals. An excellent American run master's degree program in journalism, for example, has recently been initiated under the auspices of the International Center for Journalism. The Caucasus Institute of Journalism and Media Management in cooperation with the U.S. Department of State and various NGOs is dedicated to the improvement of international journalism. Other institutions that have journalism programs include the Tbilisi Institute for Asia and Africa.

Summary

While the government or local authorities continue to use administrative levers to curb freedom of the press, the trend in the past years has been towards greater freedom for the independent media, and freedom of information. The successful use of the courts by journalists to obtain information is especially heartening. Economic and organizational problems are profound as is the need for better trained professionals. So many factors and issues are in flux that a clear picture has not yet emerged.

Bibliography

Assoc. of Georgian Independent TV and Radio Companies (Open Society-Georgia). "Georgia Media Guide 2000-2001," Tbilisi 2001. www.mediaguide.ge .

BBC News. "Country Profiles: Georgia" news.bbc.co.uk

European Institute for the Media. "Media in the CIS: Georgia" by Yasha Lange. www.internews.ru

Freedom House. "Survey of Press Freedom 1999" www.rferl.org

——. "Georgia." Nations in Transit 2001. www.freedomhouse.org

"Internews Guide to Georgian Non-Governmental Broadcasters," Tbilisi 2002 (USAID, Eurasia Foundation).

International Journalists' Network (IJET). "Murder of Popular TV Anchor Exacerbates Political Tensions in Georgia," August 2, 2001. www.ijnet.org

——. ICGF, GIPA Launch New Western-Style Journalism Programs in Tbilisi. www.ijnet.org

"Media Marketing Study," ICFS/Pro Media II, October, 2001, Tbilisi.

Parliament of Georgia. Committee for Human Rights and Ethnic Minorities of the Parliament of Georgia.

Press Freedom Overview. www.freemedia.at

"Report of the Public Defender of Georgia On the Situation of Protection of Human Rights and Freedoms inGeorgia," Tbilisi, 2001.

Telemedia. "Georgia Media and Market Overview." www.telemedia.kiev.ua

United Nations Development Program (UNDP). "Today's Technological Transformations—Creating the Network Age." www.undp.org

——. Bokeria G., Targamadze, G. and Ramshivili, L. "Georgian Media in the 90's: A Step to Liberty," Tbilisi, 1997.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). 1999. UNESCO Data Base. www.unesco.org

United Nations Online Network in Public Administration and Finance (UNPAN). "Country Profiles in Europe." www.unpad.org

U.S. Department of State. "Background Notes: Georgia." www.state.gov

U.S. Department of State. "1999 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices." www.state.govrights /

World Bank. "Country Profiles," www.worldbank.org /

Virginia Davis Nordin