Germany

Basic Data

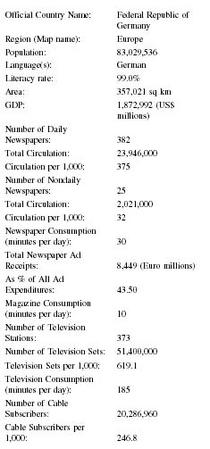

| Official Country Name: | Federal Republic of Germany |

| Region (Map name): | Europe |

| Population: | 83,029,536 |

| Language(s): | German |

| Literacy rate: | 99.0% |

| Area: | 357,021 sq km |

| GDP: | 1,872,992 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Daily Newspapers: | 382 |

| Total Circulation: | 23,946,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 375 |

| Number of Nondaily Newspapers: | 25 |

| Total Circulation: | 2,021,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 32 |

| Newspaper Consumption (minutes per day): | 30 |

| Total Newspaper Ad Receipts: | 8,449 (Euro millions) |

| As % of All Ad Expenditures: | 43.50 |

| Magazine Consumption (minutes per day): | 10 |

| Number of Television Stations: | 373 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 51,400,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 619.1 |

| Television Consumption (minutes per day): | 185 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 20,286,960 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 246.8 |

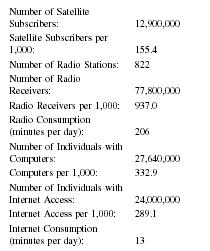

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 12,900,000 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 155.4 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 822 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 77,800,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 937.0 |

| Radio Consumption (minutes per day): | 206 |

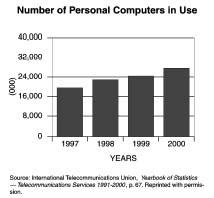

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 27,640,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 332.9 |

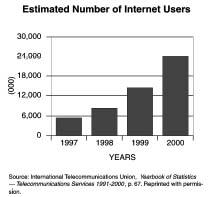

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 24,000,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 289.1 |

| Internet Consumption (minutes per day): | 13 |

Background & General Characteristics

For most of the twentieth century, Germany was in the forefront of media development and is almost certainly to exert a powerful role in the development of world media into the twenty-first century. This importance is all the more impressive when one considers that in 1945, following the defeat of Germany in World War II, the media were non-existent and had subsequently to be revived during a period of austerity and hardship. During the sixty years from the end of World War II until the beginning of the twenty-first century, the German media developed extensively; in fact, the world's second or third largest media conglomerate, the Bertelsmann Group, is German-based, and one of the German media barons of the late twentieth century, Axel Springer, rivaled in fame, power, and influence the media barons of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The evolution of the media in Germany in the post war years was heavily conditioned by the political evolution of the country. After World War II Germany was divided into the German Democratic Republic (East Germany), part of the so-called Eastern Bloc, and the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany), with its political power in Bonn and as part of the western alliance. On October 3, 1990, the two Germanys were reunited under the constitution of the United German Peoples, and on March 15, 1991 the four post-war powers overseeing Germany relinquished all occupation rights. The effect on the population was to unite the 16 million East Germans with the 64 million West Germans.

The West German media virtually extinguished the existing East German media. For example, the most widely circulated newspaper controlled by the East German regime, the Neues Deutschland went from a circulation of over 1 million to under 100,000 in less than one year. The incentive for West German media to capture this market was certainly present, for in a country of 16 million persons over 10 million read one or more of three-dozen newspapers on the market, notwithstanding strict government censorship at the time. Similarly television and radio programming was highly controlled in East Germany, and upon reunification East German television shrank, in large part because it was possible for East Germans to receive television signals from the west during the socialist era and upon reunification they continued to view programming to which they had already been exposed and which they apparently desired. In the early 2000s, newspapers and television programs produced in the former West Germany dominate the media landscape of Germany.

General Description

The target for the German media is a highly literate, affluent population that takes its media seriously. Literacy is estimated at 99 percent and, with a gross domestic product (GDP) per capita of US$23,400 (2000 est.), Germany is one of the wealthiest countries in the world. The population in Germany is highly urbanized with 87 percent of the people residing in cities and 13 percent living in rural areas. However, the spatial distribution and control of the media are based not on location of urban areas but rather on the location of the media and its public within the sixteen Länder (States) that make up the German Federation. It is the Länder that in many cases govern the media, particularly the electronic media, and it is within these regional areas that the print media deliver local and regional news. Since over 90 percent of the population is ethnic German speaking the German language, German-language newspapers predominate. However, other groups live in Germany, Turkish and Balkan people, for example.

The remarkable economic growth of the German economy in the late 1950s and early 1960s necessitated the importation of labor, and Turkish workers were actively recruited as gastarbeiter (guest workers) to work in German industry. As of 2002 there are some 2.4 million ethnic Turkish residents in Germany (3.1 percent of the population) who are generally concentrated in the cities of Berlin and Nurnberg. To meet their media needs, three Turkish newspapers are printed in Germany and seven Turkish TV programs are obtainable by satellite with one additional television program carried by cable. Of the Turkish language newspapers, the most widely read is Güncel . In addition, Turkish newspapers printed in Turkey are available. After the Balkan war between

In general the quality of German journalism is high. Journalistic traditions in Germany may be traced as far back as the Weimar Republic (1919-1933) during which time reporting was considered less important than the work of high-minded, highly articulate, and erudite editors and copywriters. Thus journalism was not at this time a dynamic profession. This trend continued during Adolf Hitler's National Socialist period when, as a result of the Editors Law of 1933 drawn up by Nazi propaganda chief, Josef Goebbels, all press was placed under the control of the National Socialist government. Since then the press in Germany has been independent, vocal, and respected, and much of its excellence stems from this respect for excellent, learned writing. Another part of German journalistic tradition derive from the immediate post-war period when the occupying forces, particularly the United States and Great Britain, sent a large number of reporters as press officers to Germany to guide journalism and in particular teach ways to gather news objectively.

Politically it may be said that the German media cover a narrower part of the political spectrum than media in other western countries. This is generally explained by the desire of the German press to avoid political extremes, both the right characteristic of the Nazi regime and the left-wing positions characteristic of socialism or communism.

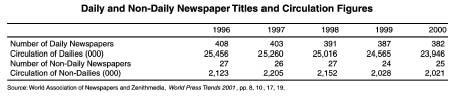

In 1999 there were 135 "independent publishing units" or businesses publishing a total of 355 newspapers that had a total circulation of 31.1 million. However, the penetration of daily newspapers in the marketplace is 78.3 percent, a slight fall from a high of over 79 percent; indeed, the number of newspapers on the market also fell in the last decade of the twentieth century. Notwithstanding these declines in readership, with a population of over 82 million persons, Germany has a readership that is among the largest in the world.

Of the 31.1 million newspaper subscribers, 17.1 million read local or regional newspapers. The only newspapers that can claim to be national in reach are Bild , Süddeutsche Zeitung , Frankfurter Allegemeine Zeitung , Die Welt , Frankfurter Rundschau and Tageszeitung . These papers generally retail for around £1.20 and are published as morning editions.

The most popular newspaper in Germany is Bild Zeitung, or Die Bild, with a circulation of 4,390,000. This size makes it the fifth most popular newspaper in the world. It is a tabloid newspaper of twelve to sixteen pages published Monday through Saturday with big letters, simple messages, often featuring female nudity on the cover or inside the front page and is the most sensational of the German newspapers. (A typical headline might read: "Child with three arms born in a German city.") As such Die Bild is the best example of yellow journalism among German newspapers. Many Germans indicate they buy it for speed of reading, television listings, and a reasonable sports section. It costs £.45 (approximately US$0.45) on the street. Bild Zeitung publishes regional editions and is generally right of center in its political orientation. In contrast, Frankfurter Allegemeine Zeitung has significantly fewer readers (approximately 400,000) but is widely known and respected both in Germany and internationally where it can be found in 198 countries. Read by the German business and political elite, it is considered one of the top newspapers in the world. National

The lengths of German newspapers vary throughout the week as various days have different topical supplements. For instance, the Süddeutsche Zeitung has no supplement on Monday, specializes in travel and science on Tuesday, Immobilienteil (real estate) both rental and sales on Wednesday, and cultural events (theater, cinema, sporting events) on Thursday. On Friday it includes a lifestyle magazine Süddeutsche magazin of about twenty-six pages. Saturday's newspaper contains all the information needed for the weekend and significantly one of the biggest Stellenmarkt in Germany, which lists jobs in Munich, Bavaria, the rest of Germany, within Europe, and beyond. On any one day the ratio of editorial to advertisements in Süddeutsche Zeitung is approximately 70 percent editorial to 30 percent advertisements. In the case of Süddeutsche Zeitung revenues are highly dependent on subscriptions, advertisements, and in particular the widely read Saturday employment section.

Weekly newspapers sell about 2.3 million on Thursday but target primarily weekend readership. The most popular and influential is Die Zeit (525,500 and costing£2.80), followed by Die Woche . In these newspapers breaking or current news is less important than news analysis and background information. As such, it is not unusual to find a newspaper over 100 pages in length in which a full page of broadsheet size may be devoted to one topic. Also important on Sunday is the publication of Sunday editions of the dailies Bild am Sonntag (3,139,900 and costing £1.20) and Welt am Sonntag (656,000 and costing £2.10). These two are the most popular Sunday newspapers and contain more pages than their weekday counterparts (twenty pages more in the case of Bild am Sonntag and forty more in Welt am Sonntag) and more human-interest stories as opposed to their daily news publications.

Germany also has two business daily newspapers, Financial Times Deutschland and Handelsblatt , the latter the more popular of the two. Of more limited weekly circulation are the two major religious publications, Deutsche Allegemeine Sonntagsblatt edited by the Protestant Church, with a circulation of 50,000 and the Rheineischer Merkur (111,000 circulation). For both of these, as Germany becomes more secular readership is declining.

A third major component of the print media in Germany is the weekly magazine. There are some 780 general interest magazines and 3,400 specialized magazines published in Germany. The former has a total circulation of 126.98 million copies and the latter 17.7 million. The oldest (first published in 1946) and most popular is Der Spiegel with 1.4 million circulation. It runs about 178 pages and in 2002 cost £2.80. Generally considered liberal in its political orientation, it has a reputation for excellent investigative journalism and critical analysis of political life and politicians that often makes its findings highly controversial. Distributed to over 165 countries worldwide and with 15 percent of its sales outside Germany, it is truly an international publication and often considered to be the printed voice of Germany overseas. For many years the weekly magazine enjoyed a virtual monopoly on this part of the media spectrum, but in 1993 significant competition to Der Spiegel emerged with the publication of the magazine Focus . The format for Focus is modeled on the successful Time and Newsweek in the United States; it has less length to the articles, more color, and a lower price than Der Spiegel . This formula was immediately successful as subscriptions rose to almost 750,000 while circulation of Der Spiegel fell. Other magazines worthy of note are ADAC-Motorwelt , the German auto club magazine, with a circulation of 13 million making it the largest in Germany; Der Stern , another leading general interest magazine that enjoys a reputation for its liberal orientation and investigative efforts but whose circulation is steadily declining; Aussenpolitik , a leading magazine dealing with German foreign affairs and available in English; German Life , a magazine on German culture designed for Americans; Aufbau , a German-Jewish newspaper in German; and finally Bunte , a typical glossy, German, and international human-interest magazine with over 120 pages which has a somewhat dubious claim to fame with its history of fabricated stories and features of prurient interest.

Finally, as in many other European countries, Germany has seen the introduction and rise in importance of free newspapers that are placed in high pedestrian traffic areas and support themselves entirely by the sale of advertisements. Local publishing houses see these publications as a threat to their operations, and legal injunctions to limit or stop their production have occurred.

As Germany enters the twenty-first century the three most influential newspapers are Frankfurter Allegemeine Zeitung for its international reputation, Die Zeit for the depth of its news analysis, and Süddeutsche Zeitung for its national importance, particularly in its coverage of the all-important Bavarian political scene. It should be noted that to this list Der Spiegel should always be appended for its journalistic excellence and international reputation and coverage while in the future the Berliner Zeitung and/or Berliner Morgenpost will be part of such a list, not for any particular strength but for their preeminence as two of the best regional newspapers and for the rising importance of Berlin as the new or reemerging German political center.

German newspapers are generally considered more regional than urban in coverage, though to affect economies of scale and to conserve financial resources the local independent presses work closely with one another and the national media and much of the contents are produced by centralized offices rather than the Heimatpresse (local press). The importance and size of German regional newspapers is noteworthy. Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, printed in the Ruhr city of Essen, has a circulation of 1,313,400, which ranks its circulation as thirty-first in the world, while the small town of Koblenz on the Rhine with 110,000 inhabitants produces a newspaper, the Koblenz Rhein-Zeitung with a circulation of 250,000. Kidon Media Services in an inventory of news sources has classified German media by Länder . It indicates the importance of Bayern (Bavaria) and the Cologne, Dusseldorf, and Frankfurt conurbations as the centers of the German publishing industry and the relative unimportance of the former East German Länder as media centers.

Finally, although German newspapers claim to be independent and apolitical, each is generally perceived to have some political bias. However, direct ownership of newspapers by political parties as was a feature of the Weimar Republic (1919-1933) or direct control as was a feature of the National Socialist era (1933-1945) no longer exist. That said, then, it is still the case that Vorwarts is the official newspaper of the Social Democratic Party, and Bayernkurier is the mouthpiece of the Christian Social Union in Bavaria. Rheinischer Merkusr is often linked to the Christian Democratic Union and as noted the Neues Deutschland is the organ of the East German Communist party (Party of Democratic Socialism). Bild Zeitung and Die Welt are generally conservative in their viewpoints and the Frankfurter Allegemeine Zeitung is generally right of center, a political stance in the Frankfurt region that is counterbalanced by Frankfurter Rundschau which is quite liberal in its orientation. In the 1980s and 1990s, Germany saw the rise of the Green Party whose main platform is environmental policies and connected issues. Many suggest that Frankfurter Rundschau is its most obvious ally in the media. Tageszeitung and Junge Welte are considered the most left wing of the national dailies with the exception of a number of Marxist ( Der Funke ) and communist ( Unsere Zeit ) publications. Tageszeitung is an interesting study for, unlike most of the newspapers that are owned by conglomerates, it is published on a cooperative base and has several thousand owners. In the first years of the twenty-first century, it was having the most difficulty in sustaining circulation amid a sea of newspapers.

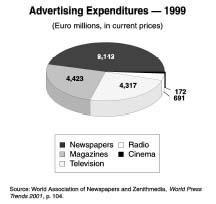

Numerous surveys indicate that the majority of Germans (51 percent) get their news from television, 22 percent from newspapers and magazines, and only 6 percent from radio (the other source, 16 percent, is from friends). Given these statistics, then, it is not surprising that despite the large number of newspapers and their popularity with Germans as a source of information, there are some disturbing trends. The number of independent newspapers has been steadily declining since the 1950s and coverage of dailies has been falling. More alarming, readership of newspapers among individuals fourteen to nineteen years of age dropped from almost 70 percent to 58 percent between 1987 and 1997. Of particular interest has been the dramatic drop in readership of newspapers in the former East Germany from 10 million in 1990 to fewer than 5 million in 1996. Sales of newspapers at newsstands have fallen and hence the increased importance of the subscription base. Finally, advertising revenues at 65 percent are the primary source of revenue (distribution and sales make up 35 percent), but the increasing competition for advertising revenues from commercial television stations is cause for concern.

Economic Framework

From the rubble of a nation it was in 1945 following World War II, Germany has risen to become the world's third most technologically powerful economy after the United States and Japan. With a GDP of $1.936 trillion (2000 est.) as measured by purchasing power parity and a growth rate of 3 percent in 2000, Germany is one of the world's economic powerhouses. In the sixty years that it took for Germany to gain this degree of economic power, printing and publishing were major contributors with 68.4 percent of the workforce engaged in the service sector in 1999 and printing and publishing contributing 2.41 percent of gross total manufacturing output in the mid-1990s. Furthermore with the growth of German publishing in the former Eastern Bloc and other European Union

Concentration of Ownership and Monopoly

Media development during the 60 years following World War II was closely tied to the relationship between the government and the private sector and in particular the rise of large media conglomerates that as of 2002 dominate both the German media and to some extent the national political agenda. In contrast to the electronic media, the print media is privately owned and operated. The rise of the private, independent German media conglomerate is best exemplified by the rise to dominance of the Axel Springer Group, Germany's major newspaper and magazine publisher with interests also in books, film, and Internet development.

Axel Springer was born into a publishing family in Hamburg, but his empire can be traced to 1946 when the British military government in Hamburg permitted him to open a newspaper. He went on to launch a number of other newspapers in Germany most notably Hamburger Abendblatt in 1948 and Der Bild in 1956 and to acquire existing newspapers such as Die Welt in 1953 and Berliner Morgenpost in 1959. By 1968 it was estimated by the German government that Axel Springer published 40 percent of German newspapers, 80 percent of all German Regional newspapers, 90 percent of all Sunday papers, 50 percent of weekly periodicals, and 20 percent of all magazines. This market share represented two-thirds of all papers sold in German cities. Axel Springer died in 1985 but the pattern of acquisitions did not cease with his death. The 1990s were marked by expansion into Central and Southern Europe as the European Union expanded and as the former Eastern Bloc privatized former state media concerns. By 2000 the Axel Springer Group had annual sales of over DM5 billion and around 14,000 employees.

During Axel Springer's rise to prominence a parallel German conglomerate, the Bertelsmann Group, was working in other areas of the media and enjoying similar growth. A publishing house that got its start printing Bibles in the nineteenth century, Bertelsmann has wider interests than Springer, particularly in books, electronic media, and music recording. It is the world's second or third largest media conglomerate as measured by revenues with over US$16 billion (76 percent outside Germany) and 76,000 employees. In Germany its most notable publications are the most popular women's magazine, Brigitte and the weekly Der Stern , and it has a 25 percent stake in Der Spiegel . As a result of its lack of emphasis on newspapers, in 1999 Bertelsmann trailed Axel Springer in print circulation. Axel Springer Group enjoyed 23.7 percent of the circulation market share while Bertelsmann's Gruner and Jahr division enjoyed 3.4 percent. (With regards to the other three large media groups, Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung Group has 5.9 percent market share; the Stuttgarter Zeitung Group, 5 percent; and the DuMont Schauberg Group in Cologne, which is responsible for the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , controls 4 percent.)

In total the ten largest publishers of dailies account for 54.8 percent of the market, and the four largest publishers of magazines enjoy 63 percent market share. This situation has given rise to an ongoing debate in Germany over the perceived monopolies of the large publishing houses and the possible need to reduce them. Most Germans are not concerned so much with the issue of monopoly as with the degree of perceived influence that such publishing houses have on political opinion and decision-making.

Control of the electronic media is different. Dominated by public broadcasting stations until the 1980s, it was traditionally independent and non-commercial but financed by license fees and subsidies and controlled by the Länder . These stations were and continued in the early 2000s to be answerable to public sector supervisory councils that influence programming and content. This situation changed dramatically in the 1980s with the advent of cable and satellite systems through which private interests could enter the TV market. Private stations are identifiable by the broadcast of numerous commercial messages by which they finance their operation. In addition the existing Länder legislation, particularly that delineating the supervisory roles of the council was anachronistic for the technology and content, and dramatic changes were required to address this new part of public broadcasting, particularly since by the turn of the century its market share was larger than that of the public broadcasting stations and increasing yearly. The power of television and its importance in the German media mix are such that political parties have become increasingly involved in policy decisions on such items as accountability, rating share, and most recently anti-monopoly concerns. Generally the relationship with German political parties has been that the conservative CDU favors privatization and more commercialization while the SPD favors the public service broadcasters.

Trade Unions

The trade union movement is strong and influential in Germany, particularly in the media world. In the early 2000s the union movement is undergoing some reorganization, in large part as a reaction to the government's efforts to reduce the range of benefits and perquisites that union members enjoy. Politicians and economists are driven by the fact that in comparison to other countries, Germany is seen as having excessively generous worker benefits that some believe make it un-competitive. Unions have a rather long history of strikes in the production departments of newspapers but rarely in the editorial offices. The most protracted and serious of these, insomuch as it was over structural change, came in the 1970s and concerned the implementation of new techniques of production.

Newspapers began using personal computers to file stories and thus German newsrooms changed. Plus, new printing presses streamlined the production process and thereby displaced workers. In the early 2000s Germany is at the forefront of new printing and editing technologies. Strikes in the German press seem to occur every two or four years, which is correlated to the prevailing contractual length. The dispute issue is usually connected to wages, and a newspaper may be on strike for some two to three weeks during which time the delivery of the daily newspaper is suspended.

Employment & Wage Scales

Employment in the media in Germany is generally considered to be not lucrative. Wages for a beginning journalist in a small local or regional newspaper (50,000 circulation) is under US$50,000 per annum gross with a significant proportion of that going to taxes, health care, unemployment, and pension contribution. Salary in this case may consist of a base salary with incentives for the number of articles written by the journalist that the newspaper prints. In the larger cities and at a more prestigious media outlet, salaries may rise to around US$100,000. However, the high cost of living in Germany necessitates a modest middle-class lifestyle. Executives, TV anchors, and personalities can of course command far greater salaries and benefits. The German media use freelancers.

The fact that federal and state governments employ much of the electronic media is cause for political concern because of the excessive bureaucracy. In order to reduce this number, freelancers are hired because stations do not have to pay them benefits. Freelancers are not on a fixed salary and are free to negotiate their own remuneration and indeed they may work for a number of outlets. As a result freelancer incomes tend to be significantly higher than salaried employees at radio and television stations. Such freelancers also exist in the print media, the most famous example being the paparazzi (photojournalists) who sell salacious material to purveyors of yellow journalism. In 1995, some 40,000 persons were employed in television broadcasting and 11,400 in newspapers (the latter figure is from 1990 on the eve of reunification at a time when East German media were grossly over-staffed), but these figures do not take into account the large number of persons employed as free-lancers or working in the large multi-national media conglomerates and the distribution network.

Distribution

Most print media companies have their own distribution company, but there are also private distribution houses, which distribute a number of smaller newspapers, magazines, leaflets, and brochures. There is rarely a shortage of newsprint in Germany and prices paid reflect international rates.

Press Laws

Freedom of the press in Germany emanates directly from the German Grundgesetz ("Basic Law," or constitution), which states under Article 5 (Freedom of Expression):

- 1. Everyone has the right freely to express and to disseminate his opinion by speech, writing and pictures and freely to inform himself from generally accessible sources. Freedom of the press and freedom of reporting by radio and motion pictures are guaranteed. There shall be no censorship.

- 2. These rights are limited by the provisions of the general laws, the provisions of law for the protection of youth and by the right to inviolability of personal honor.

- 3. Art and science, research and teaching are free. Freedom of teaching does not absolve from loyalty to the constitution.

While the freedom of the press and all that usually is associated with press freedom (confidentiality of sources and notes, refusal to identify sources, free access to sources) might thus be seen to be as inviolable, there are provisions for recourse in the event of perceived press violation of ethics. In particular, the Press Council is a major counter measure to full press autonomy, and legal recourse is often used. This may involve the agreement to stop printing factual errors, the agreement to print an apology or retraction, and even civil proceedings to obtain monetary damages in the most serious cases. Perhaps the most whimsical example of this was the cease and desist order directed to those in the press that falsely claimed Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder used hair coloring to remove gray from his hair.

The constitution removes the right to publish "writings which incite to racial hatred or which depict cruel and inhuman acts." In the penal code relating to offences against the state, it prohibits "betraying the country and endangering external security by betraying state secrets." Germany possesses the full range of libel, blasphemy, and obscenity laws. Interestingly, however, Germany is the only country in Europe that does not have a Freedom of Information Act. The argument against passage for such a law is that it is implicit within the Basic Law and that moreover it is a Länder responsibility. In this regard only four Länder have adopted Freedom of Information legislation (Brandenburg, Berlin, Schleswig-Holstein, and Nordrhein-Westphalia). Other Länder have proposed Freedom of Information legislation, but Bavaria, Hesse, Saxony, and Baden-Württemburg have voted down Freedom of Information legislation.

As the Federal Republic of Germany is a federal state, press law is largely a Länder responsibility, the Constitution setting the framework for the individual Länder legislation. Most Länder press laws were passed between 1964 and 1966 and upon the reunification in 1990 the existing models were used in the new Länder . The most important provisions the press laws enunciate are: the public duty of the press; the right of the press to information; the duty of the press to be thorough; identification of author or imprint; the duty of the editor; the clear distinction between advertisement and editorial; and the right of reply, regardless of veracity. All of these obligations are set out by each Länder in the form of a code of conduct called a Presskodex.

Perhaps the most controversial part of the code of conduct comes in the area of protecting the privacy of non-official citizens. The codex states under Article 8:

The press shall respect the private life and intimate sphere of persons. If, however, the private behavior touches upon public interest, then it may be reported upon. Care must be taken to ensure that the personal rights of uninvolved persons are not violated.

The problem arises in the definition of "intimate sphere" and "public interest," and, in the case of the German media, the yellow nature of much of the journalism. The desire for salacious material on public figures, such as politicians, athletes, movie stars, and other performing artists, often finds the German media on the edge of what is permissible and what is excessive. One notorious case of invasion of privacy is the so-called "Caroline Case." In March 1992 the magazine Bunte published an article that purported to be an interview with Princess Caroline of Monaco, a reclusive and press-shy individual. Unfortunately the interview was entirely fabricated. The result was an DM180,000 compensation settlement.

Commonly German newspapers will publish the facts as the newspaper sees them but will not reveal the name of the central figure in those cases where scandal and sensationalism are presumed present. Rather they will print a fictitious name or only the given name and not the family name, for example a column may read: "Richard B. was charged." This practice is obligatory in court cases to protect the accused. In the case of politicians, coverage is extensive but rarely involves family and indeed extra-marital relationships are also deemed private matters.

One common feature of German newspapers is the gegendarstellung (opposing interpretation). It is a consequence of the right to reply provision in the codex and is an expression from a complainant who believes he or she has been misrepresented. It involves the printing verbatim of the facts as the complainant interprets them. Remarkably, the compainant's response does not have to be true. It only needs to state a contrary view of the facts as the complainant sees them. In many Länder , the newspaper is permitted to state it is obliged to print the piece (usually by the courts) and does not necessarily agree with the sentiments expressed in it.

In the Federal Republic of Germany there is no registration of journalists though Article 9 of the codex attempts to describe a "responsible journalist." Generally, journalists in Germany have some form of higher education, though particularly in the case of photojournalists newspapers and magazines will pay significant sums of money for freelance material, particularly if it is salacious, unique, or constitutes a "scoop." There are no licensing requirements to be met before newspapers can publish, no bonds required, and the independence of the judiciary is not questioned.

Censorship

In Germany there is no official censorship, but as a result of the Fascist period of government and the desire to expiate the past, Nazi propaganda and other hate speech are illegal. As a result, the Freedom House Survey of Press Freedom of 1999 gave Germany one of the highest ratings for freedom of the press. In 1997 in response to concerns over child pornography and the Internet, a bill to regulate standards for child protection on the Internet was passed. It defines which online activities should be subject to licensing and other regulatory requirements. As a result of a rise in crime and the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, a constitutional amendment was introduced to restore broad police surveillance powers. Journalists among other professionals, however, would be exempt from bugging.

As was noted above, while there is no agency concerned with monitoring the press, Germany has an active Press Council that oversees the functions and operation of the print media. In view of its importance and influence it is worth examining in some detail its make up and mandate.

Self-monitoring Systems

The German Deutscher Presserat (Press Council) owes its origins to the need following World War II for a body that was independent of the government to monitor the media and provide recourse for media disagreements. Formed on November 20, 1956, the German Press Council is modeled after the British Press Council. Statutes adopted on February 25, 1985 and updated in 1994 govern its structures and duties. According to Article Nine, the Press Council has the following duties: to determine irregularities in the press and to work toward clearing them up; to stand for unhindered access to the source of news; to give recommendations and guidelines for journalistic work; to stand against developments which could endanger free information and free opinions among the public, and to investigate and decide upon complaints about individual newspapers, magazines, or press services.

The Press Council consists of a consortium of twenty representatives from journalist and publisher associations. The members' assembly addresses legal, personnel, and financial matters of the body but are not involved in matters of competition and pricing. A ten-member complaints commission is an important policing unit. It should be noted that this body is entirely self-monitoring with no external authority, such as an ombudsman, involved in the decision-making process of the council. It is estimated that the council receives on average 300 and 400 complaints per year. In practice most complaints against the press are dealt with quickly and effectively, often by use of the printed apology, notes of censure, or public reprimand. Examples of the latter include reprimands for the naming of suicide victims, publication of photos of corpses, and non-authentic photographs of stories being covered. Some observers believe that the receipt of such a reprimand by a newspaper or magazine is generally seen as a black mark and is to be avoided if at all possible, while others point to the content and practices of those yellow publications and suggest that the influence of the Press Council is limited. To assist in their advisory role the Press Council provides a series of guidelines for editors and journalists to which they are advised to adhere.

The most relevant oversight body monitoring the broadcast media is the Rundfunkrat (Independent Broadcasting Council). This body, set up under the Länder , regulates the public service broadcasters. As a result of a constitutional court ruling, the Rundfunkrat is required to be made up of "socially relevant groups." It is composed of members of a wide range of public interest groups such as political parties, business, and labor organizations, churches, farmers, sports, women's groups, and cultural organizations. As such, it is supposed to be free of political control and influence, but in fact, party interests can become significant determinants of policy. Complaints against the broadcast media can be brought before these councils for resolution.

Satellite and Cable Issues

The advent of satellite and cable systems as a means of communication necessitated new media laws to be drafted by the Länder to regulate media outside the existing public broadcasting regulations. Of primary necessity was the need to establish a mechanism for allocating licenses and determining what programs were to be fed into the cable systems. For this purpose, new Länder bodies, the Landesmedienanstalten , were created. These bodies closely resembled the existing supervisory bodies for the public network. By 1991, these bodies were present in the former East Germany, and in the early 2000s they govern the cable and satellite industry. As a result of criticism brought against commercial television that their offerings were particularly harmful to children, some commercial broadcasters employ a commissioner for youth protection, the Jugendschutzbeauftragter , that reports to the company. There are also planned informal advisory councils to advise commercial television stations on content and acceptability.

In the realm of advertising the Deutscher Werberat (German Advertising Council) has members from the media and advertising agencies who receive complaints and publish their decisions in a handbook. The lack of consumer representation on the twelve-person council has been cited as a major drawback to its effectiveness.

State-Press Relations

Generally, the press does not abuse the German constitution which gives in practice perhaps the most wide-ranging press freedoms in the West. When the German media cover the political scene, the treatment is generally less emotional and less sensationalized than that in many other countries. Media observers attribute this objectivity to a strong organizational control in the German corporate press organization, in which reporters' opinions and criticisms are subsumed in those of the editor and lead writers. Thus rarely will one find political opinion within a story, but rather a concentration on news and business. Indeed, at election times newspapers rarely endorse one political party or candidate.

Political scandals and their effect on public life and democracy are another area of concern. The combination of the constitution, the press laws, and the Press Council codex have the effect of making the German press much more discreet and confidential than its counterparts in many western countries. However, this may be changing as several surveys indicate a decline in public attitudes towards politicians connected to scandals. Moreover it is apparent that editorial comment on such scandals strongly influences government responses given the emphasis the German public places on receipt of its news from all media sources.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

The German press is an open system and as such, foreign media are accepted and contribute to a wide range of views. Indeed the evolution of the German media has been one not of protection from foreign media but rather integration to every possible extent with foreign media in order to effect growth and variety. Thus, cable systems first started with a Luxembourg-based station (RTL) and continued with such broadcasters as ARTE (a Franco-German cultural channel that is a consortium of ARD, ZDF, and the French channel La Sept), while satellite television is closely integrated with Austrian, French, Swiss, and U.S. national television stations. Deutsche Welle, as the international voice of Germany, has been particularly active in broadcasting German television programs to thirty-one countries worldwide from Berlin. Deutsche Welle Radio transmits by satellite around the globe to twenty-nine nations while Deutsche Welle World provides a multimedia service on the Internet. In the print media foreign magazines like Paris Match , Elle , Vogue and W are eagerly bought in Germany and other western newspapers are freely available. Moreover, most European media have significant representation in Germany in the form of German correspondents along with news bureaus like Reuters, Bloomberg's, AP and Agent Presse France. The German domestic news agency is the Deutsche Presse Agentur (DPA) based in Hamburg.

Broadcast Media

The German electronic media is a little like that of the BBC, but the influence and role of the sixteen Länder make it somewhat different. At the basis of the German electronic media is the provision in the federal constitution that the Länder administers radio and television. This was enacted in 1949 to ensure against no repetition of the type of state control exercised by the National Socialists during the time of the Third Reich. In 1954 the first public sector broadcasting corporation, Arbeitgemeinschaft der Rundfunkanstalten (ARD), was formed as a consortium of Länder and in the early 2000s employs 23,000 people with an annual budget of US$6 billion. The second public broadcaster, Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen (ZDF), was formed in 1961 and is a separate corporation with an agreement with all Länder to produce national programming. These public service broadcasters are marked by the production of regional news, cultural coverage, and educational programming, such as documentaries and current affairs programs. Advertising is limited to thirty minutes per day and no advertising is allowed after 8:00 p.m. or on Sundays.

This monopoly was eliminated in 1981 when Länder recognized their right to grant broadcasting licenses to private companies, which was passed into law in 1987. Concomitant with this legislation was the provision throughout (West) Germany of a national cable network provided by the Deutsch Telekom (federal post office) which today owns all the cable systems and which claims to be the world's largest cable network provider. The recent ruling by the European Union that telephone and cable systems should be "unbundled" or under separate ownership has led to a sell off of some of Deutsch Telekom's cable assets. By the end of the millennium, of the 33 million households that had television (owning 54 million TV sets), 70 percent had access to cable, though of the 6.6 million households in the former East Germany that had television only 12 percent had access to cable. All German television owners are required to pay a license fee with a supplementary fee required for cable subscribers.

The entrance of private companies into the TV market raised new fears of monopolies and excessive control by media conglomerates. In 2002 German commercial television is controlled by two media groups, first the Bertelsmann conglomerate that broadcasts in conjunction with a Luxembourg-based corporation and the Kirch conglomerate (headed by another German media mogul, Leo Kirch). Kirch obtained his power by buying the rights to broadcast a wide range of international programs (which are usually dubbed into German) and sporting events and which, owing to the number of rights that he holds or are under his control, is now seen as a de facto monopoly on commercial programming.

It is generally agreed that the programming on cable is much more commercial and somewhat more down market (there is a range of reality television shows, game shows, human problem confrontational shows similar to the Jerry Springer show in the United States, talk shows, and a number of pornography channels). Much of the programming on cable has been copied from the United States where similar shows have proven to be audience draws and which apparently draw German viewers. This trend in television has affected the programming on the two public service channels, ARD and ZDF. In an attempt to meet the challenge from the commercial stations, the government has decentralized control of the programming, reduced state subsidies leading program directors to turn toward more commercial type programming. For example, one of the most popular TV programs on ARD is "Tatort," a crime-based soap opera in which viewers follow the work of a detective and his helpers as they expose and combat serious incidences of crime. Its success is such that it is syndicated throughout Europe. In contrast, the reduction in state subsidies and the emphasis on commercial success have meant that the German public television history of serious documentaries has lessened, for funding for such programs is now increasingly difficult to obtain. Notwithstanding the lessening importance of the German Public Broadcasting system, ARD and ZDF still command significant audience shares during their peak viewing hours (which in the case of ARD is at 8:00 p.m. and ZDF 7:30-8:00) on weeknights when the national news ( Tagesthenmen and Tageschau ) is broadcast, as well as on Saturday nights when the most popular TV show in Germany, Wettendas is shown on ZDF. This is a celebrity talk show with a game show component and a very popular host, Thomas Gottschalk. According to a 1990 survey, 49 percent of West Germans and 70 percent of East Germans watch the evening news at least five times per week.

In 1985 with the broadcast of SAT-1, satellite television became part of the media mix in Germany. While Kirch owned a large part of all SAT channels, other new entrants to the satellite market quickly emerged. Two new all-news channels appeared in 1993, one owned by Time Warner/CNN and the other, VOX, by Bertelsmann. By 1996 Kirch had introduced digital satellite TV and at the turn of the century claimed 2 million subscribers paying DM55 for service including the necessary decoder.

German radio is losing importance in the twenty-first century. As noted, only 6 percent of the public get their news from the 77.8 million radios in Germany. There were fifty-one AM stations, 767 FM stations, and four short-wave stations in Germany in 2000, with commercial radio dominating the airwaves. A city the size of Hamburg might boast over ten commercial radio stations providing programming for the full spectrum of market interests. Two German radio corporations, Deutschland-funk (DLF) and Deutsche Welle (DW), intend to provide

Electronic News Media

An estimated 24 million Germans have access to the Internet with 625 Internet providers in the country while at the beginning of 2000, some 176 German newspapers offered online news. As for the rest of the western world, it is difficult to assess the impact of its availability in Germany. What generally is known is that 73 percent of users are under forty years of age, of higher median income and education level, and usually male; most read online news from their residence and generally read their local newspaper. Only 29 percent read their news daily as opposed to 56 percent who read their print newspaper, and they read for a shorter time and a more limited range of topics in the newspaper. For the newspaper the issues are still ones of familiarity (it was estimated in 1989 that the median age of reporters in German newsrooms was 50 years) for an aging workforce, financial considerations, and lack of knowledge on how to market their product. In the early 2000s use of the print layout seems to be the normal method. However most German sites keep the news current and relevant.

Education & TRAINING

Media education in Germany constitutes a large portion of the German higher educational system. The central registry of degree programs for Germany indicates that there are only twenty degree programs in Germany that award a degree in journalism, but in the more general

This trend toward media studies grew particularly in the 1980s and 1990s. The burgeoning interest resulted in a large number of graduates with very few positions available in any one year. For example, a small regional newspaper or radio station may hire only one or two new people every year and even the larger national newspapers hire infrequently, making the job market very competitive. This situation is exacerbated by the fact that many of the publishing houses or larger newspapers have Volontariat (apprenticeship) programs. While this system is not as prevalent in the early 2000s as in the twentieth century, it is still a significant option. Many media observers note that to obtain a position in the German media today a doctorate is almost becoming a necessity.

The most prestigious institutions for training journalists are the Munich Journalism School and the Hamburg Journalism School. Entrance is highly competitive for both programs, with fewer than one hundred students graduating from each institution annually. These schools owe their reputations in large part to loose affiliation with Süddeutsche Zeitung in Munich and the Axel Springer organization in Hamburg. It should also be noted that German media have been at the forefront of training media in such areas as investigative journalism, media management, and business planning in the newly emerging states of Central Europe, Russia, and Central Asia.

There are two major professional organizations representing journalists. One is Deutscher Journalisten Ver-band (German Journalists Association, DJV) that calls itself a trade union. It is not, however, affiliated with trade union organizations but rather acts as a professional lobby group. The second organization is the Deutsche Journalisten Union (German Journalists Union, DUJ), a member of the German Trade Federation. Both organizations provide ongoing training for their members, as does the European Journalism Center, an independent nonprofit training institution. As media boundaries and borders in Europe become more permeable, the goals of the EJC become more relevant. EJC goals are: to further the European dimensions in media outlets; to enhance the quality of journalistic coverage; to analyze and describe the European media landscape, and to provide strategic support for European media.

In view of the fact that the German Press Council is made up of both journalist representatives and publishers representatives, Bundesverband Deutscher Zeitungsverlager (BDZV), should be noted as the representative of the owners and publishers, while the Verband Deutscher Zeitschriftenverlager (VDZ) represents the magazine publishers. Similarly, while not members of the Press Council, but important as the industry voice in the regulation of the broadcast media, the Verband Privater Rund-funk und Telekommunikation (VPRT) operates as the voice of commercial radio and television.

Awards

The overall excellence of the German media has garnered a large number of journalistic awards and prizes. For example, in 2001, two of the three "World's Best-Designed Newspapers" were, for circulation of 175,000 or more, Die Zeit ; and for circulation in the 50,000 to 174,999 range, Die Woche .

In 2002 nominated as part of the sixteen finalists in the "World's Best-Designed Newspaper" in the 175,000 circulation and above category were Die Welt and the Berliner Zeitung . They were competing in the final with such newspapers as The New York Times , the Detroit Free Press, and the St. Louis Post-Dispatch from the United States; from Canada The Globe and Mail ; and from England, The Guardian , The Independent , and The Observer. The winners in the category of 175,000 circulation and above were The Hartford (Conn.) Courant , the National Post , Ontario, Canada; and Die Welt , from Berlin, Germany. In the same competition Die Woche won the best newspaper award for the category of 50,000 to 174,999 circulation while Die Zeit won awards for " other news" and Die Weltspiegel won for its Science and Technology pages. With thirteen awards Germany received the largest number of awards of any nation.

Summary

Perhaps the one factor that arises from an examination of German media is the importance it plays in German intellectual life and debate. Indeed, German media is one of the most powerful opinion makers in European, or indeed world, media for it is a highly analytical and critical tool that leads to articulation of important subjects. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, Germans debate about their past, especially under Hitler, and also turn a critical eye to politicians in their midst. The early 2000s witness a mood of disillusionment with the electorate, particularly the disgrace of former Chancellor Helmut Kohl who allegedly received large amounts of campaign contributions from industry sources. Critical analysis is the hallmark of the modern German press. Particularly at the national level, the outlook for the media in the twenty-first century is inextricably bound up with the existence of the public broadcasting networks, both radio and television. The most fundamental question is whether there is a role for state subsidized electronic media in Germany at all or whether full privatization is necessary or desirable. One problem with public broadcasting systems is the amount of investment needed for both new technologies and programming, a cost that is usually not borne by license fees or state budgets that are increasingly looking to be reduced rather than increased. In order to raise this kind of money, public broadcasting stations need to become more commercial or more revenue oriented and in order to do that, they must emulate the existing commercial operations. In the early 2000s, advertising provides roughly one-third of television revenues and one-fourth of radio revenues. If public broadcasting stations are to become more financially viable, this proportion must surely increase. They must now find a new niche in an increasingly commercial media.

At the international or global level, much like in the rest of the western world, the mission of the German media is to embrace the phenomenon of globalization. The late 1990s saw the growth of large media conglomerates, of which Germany had a significant number. These conglomerates embarked upon a strategy of vertical and horizontal integration marked by convergence of telecommunication and information technology and in particular the integration of print media, broadcast media, and the Internet. By the year 2002 as the stock market was reflecting increasing difficulty and excessive cost in achieving that convergence, the wisdom of such convergence was being reexamined. With the importance of large media conglomerates to Germany, any strategic miscalculation could have a significant impact on German economy as a whole. Thus, the outlook for the twenty-first century must be one of guarded optimism, fuelled by the incredible success story of the past sixty years but possibly tempered by the structural difficulties and rigidities that once made the economic miracle happen.

Significant Dates

The most significant highlights of press history during the past ten years have been the requirements within the media to integrate the former East Germany into the federal system of media operation.

- October 3, 1990: The two Germanys are reunited under the Constitution of the United German Peoples.

- 1990: The German constitution or "Basic Law" ( Grundgesetz ) is amended by the Unification Treaty to include the former East German Länder on August 31 and by Federal Statute on September 23.

- 1990: National framework of regulations between Länder ( Medienstaatsvertrag ) is extended to new Länder which join the federal republic under reunification. This action is completed in 1991.

- 1994: On February 23, the Public Principals of the German Press Council are updated.

- 1996: Digital television arrives in Germany.

Bibliography

Eggleston, Roland. "Germany: Complex Press Regulations Attempt to Divide Public, Private Spheres," Radio Free Europe and Free Liberty (May 1998). Available at http://www.rferl.org/nca/features/1998/05/f.ru.980527114711.html .

Embassy of the Federal Republic of Germany. "Germany Info." Available at http://www.germany-info.org .

Esser, Frank. "Editorial structures and Work Principals in British and German Newsrooms," European Journal of Communication , vol. 13, issue 3 (September 1998): 375.

——. "Tabloidization of News: A Comparative Analysis of Anglo-American and German Press Journalism," European Journal of Communication, vol. 14, issue 3 (September 1999): 291.

The European Journalism Center. "European Media Landscape." Available at http://www.ejc.nl .

German Culture. "Newspapers in Germany" and "Radio and Television in Germany." Available at http://www.germanculture.com .

"Grundgesetz : Basic Law (German Constitution)." Available at http://www.library.byu.edu .

Ketupa Net Profiles. "Axel Springer—Profile" and "Bertelsmann—Profile." Available at http://www.ketupa.net .

Kidon Media Center. "Newspapers and Other Media Sources from Germany." Available at http://www.kidon.com .

Neuberger, C., J. Tonnemacher, M. Biebl, and A. Duck. "Online: The Future of Newspapers? Germany's Dailies on the World Wide Web." Available at http://www.ascusc.org/jcmc/vol4/issue1/neuberger.html .

Richard W. Benfield

Thanks and waiting for your reaction