Italy

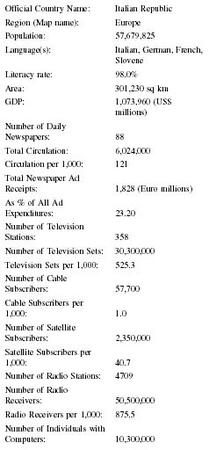

Basic Data

| Official Country Name: | Italian Republic |

| Region (Map name): | Europe |

| Population: | 57,679,825 |

| Language(s): | Italian, German, French, Slovene |

| Literacy rate: | 98.0% |

| Area: | 301,230 sq km |

| GDP: | 1,073,960 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Daily Newspapers: | 88 |

| Total Circulation: | 6,024,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 121 |

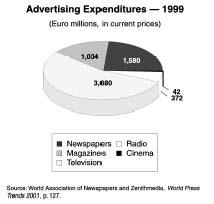

| Total Newspaper Ad Receipts: | 1,828 (Euro millions) |

| As % of All Ad Expenditures: | 23.20 |

| Number of Television Stations: | 358 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 30,300,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 525.3 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 57,700 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 1.0 |

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 2,350,000 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 40.7 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 4709 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 50,500,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 875.5 |

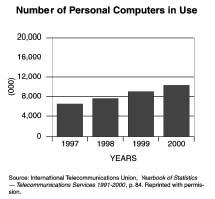

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 10,300,000 |

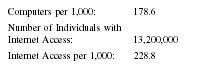

| Computers per 1,000: | 178.6 |

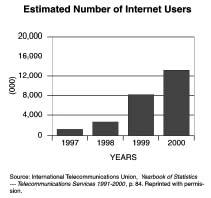

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 13,200,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 228.8 |

Background & General Characteristics

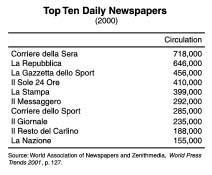

The Italian media system entered the new century with a combination of continued reliance on the traditional printed press and participation in the global shift to new delivery systems, including online journalism, the spread of personal computers, and digital television. Despite increasing reliance on digital technologies in every area of communication in Italy, the term "press" still mainly connotes the daily newspapers. Italy's daily newspapers have five distinguishing characteristics that set this medium apart from its counterpart in other west European countries: historically low levels of readership; a predominance of regional over national papers; a notable lack of independence of the press; virtual nonexistence of a popular press; and the existence of a group of daily "news"papers that are devoted solely to either sports, religious news or other specialized topics.

The first characteristic is the one most often stressed by analysts of the Italian press. Compared with other member countries of the European Union (EU), Italy's aggregate daily newspaper circulation (the social indicator used as a proxy to measure readership) ranks just above Greece and Portugal, the two least advanced Mediterranean European Union (EU) members. Paolo Mancini reports that aggregate daily newspaper circulation in Italy stood at 109 per thousand citizens in 1999, and he remarked that this is very low indeed when one considers that the comparable figure is near 600 in Norway (323). Throughout most of the twentieth century, readership of daily newspapers was constant at about five million. There was a small increase in the 1980s, fueled by a turn to commercialization of the press, to a high 6.5 million in the year 1990. Since then, the number has been falling again, to 6 million in 1998 (ISTAT 214). This figure of 6 million was computed by taking the annual circulation of daily periodicals, (2.2 million) and dividing by 365 days. This also means that aggregate daily newspaper circulation has decreased to 105 per thousand persons.

There are several direct and indirect causes of the low-readership phenomenon. A direct cause is related to the logistics of matching the reader with the paper. As is typical in other European nations, newspaper distribution in Italy is conducted almost exclusively via newsstands. However, for a variety of reasons related to permit requirements and attempts by operators to limit competition, the number of newsstands in Italy per 1000 persons is below that in Germany and France. Another technical problem is the fact that prices are determined by a joint committee of government and business, and have inevitably crept up. In addition to pointing to availability of newsstands and price per copy, we can address the obvious question: do Italians simply not read in general? True, Italians are not avid readers, but this statement needs to be qualified.

According to a survey conducted in 1956 (Lumley 4), nearly two thirds of the population reported never reading anything at all. Regional differences are significant, however. Until the fifties, Italy's population outside the major urban centers was mainly rural and poor, and illiteracy was still fairly high in the Mezzogiorno region and in rural areas in general. Almost four fifths of the population spoke a local dialect and were not very familiar with Italian. In some local dialects, the lira was referred to as the franc, while in another it was called a pfennig, which lends testimony to Italy's much more fragmented history. Italian is still in the process of becoming the language that every Italian is comfortable with, and much of the new vocabulary, including technical and specialized language transliterated from other languages, was slow to trickle down to the less educated tier of the population. More often than not, Italian journalists writing for major daily papers did not engage in concerted efforts to translate or explain unfamiliar words to their reading public.

Literacy rates increased in the next two decades, and most Italians were now able to read a newspaper. Yet, they still chose not to do so, for a variety of reasons, including alienation from bureaucracy and journalistic jargon used by the press, the non-availability of popular magazines and dailies, and the fact that a high proportion of the potential readership, women in particular, felt excluded from the mainstream public sphere (Lumley 4). Other types of media have a higher appeal to this population. Since the 1950s, radio and TV were the media of choice. More recently, it is not surprising that newspaper circulation decreased in the last decade, due to increased reliance on the Internet for access to daily news.

The predominance of regional over national newspapers in Italy is striking. One reason for this phenomenon is that the capital, Rome, is not an international center on the order of New York, Paris, or London, while several cities in northern Italy, notably Milan and Turin in the northwest, Bologna and Venice in the northeast, are important urban centers. While some regional newspapers have a high circulation and are nationally distributed, they tend to convey a regional bias that is often linked to the family that owns the paper. This has been the case for Il Corriere della Sera , whose owners have long imposed their own Milanese bias, and for La Stampa , owned by the Agnelli family of Turin, who are the major stockholders of the Fiat Company and who impart a Piedmontese bias to this nationally distributed paper. The lack of a truly national newspaper leaves room for many regional and multi-regional papers, e.g. Il Mattino , which is based in Naples and Il Resto del Carlino , based in Bologna (Lumley 2). Some party-affiliated daily newspapers, notably L'Unitá , and other sectarian daily newspapers have a truly national character and nationwide readership, and seem to be filling the void to some extent.

The third characteristic of the Italian daily press, its lack of independence, is intertwined with the previous one. Ownership by rich families, industrial groups and other financial power centers is typical, with often many newspapers published by the same group. A notable non-industrial financial center is the Catholic Church, which supports publication of the widely circulated daily paper of the Vatican, L'Osservatore Romano . In past decades, it was also typical to see daily newspapers published by political parties, which used the medium to circulate information to their members. While the Italian reading public is small, it is politically savvy. Italians display high percentages of party membership and voting turn-out, and membership is also high in labor unions and in a variety of cultural, professional and political interest groups (Mancini 320-1). Party newspapers could thus derive great political benefit from this method of communicating with their members. While most of the party papers have disappeared in the past decade, L'Unitá , the traditional publicity arm of the Communist Party (recently reborn as the Democratic Party of the Left) is still circulated nationwide, but has declined in importance.

One origin of Italy's press sectarianism is the genre of journalism that historically developed in Italy. As is the case in several other west European countries, journalism in Italy has grass-root beginnings in literary gazettes. As such, journalism has traditionally specialized in interpretation, intricate commentary and complex analysis rather than direct news reporting and detailed descriptions of events. Italian journalists are experts at the inchiesta giornalistica , the investigative in-depth report. Analysts of the Italian daily newspapers often note the irony residing in the fact that this medium of public discourse employs highly skilled journalists who face a public that does not read daily newspapers in significant numbers. Other origins lie in the fact that the press developed at the time of unification of the country, which fostered the founding of the Party newspapers, and the fact that the seat of power of the Catholic Church happens to be in the Italian peninsula. The Vatican is the world's richest nation in terms of income per capita, and it constitutes one of the main power bases, with a political agenda that is definitely not independent.

The final two major characteristics of the Italian press, non-existence of a popular press and the presence of daily newspapers devoted to a single non-news topic, are to some extent overlapping. Instead of producing tabloids, a format that is popular in several other EU member countries, Italian publishers focus on newspapers with specialized topics that tie in with a major passion of all Italians, sport, and in particular soccer. On days following a national soccer match or a World Cup competition, the circulation of sports papers like La Gazetta dello Sportand Il Corriere dello Sport-Stadio soars into the hundreds of thousands (Grandinetti 29, 40).

Daily, Weekly & Other Periodicals

According to the most recent statistics ( Annuario Statistico Italiano 214), slightly over 10 million distinct periodicals appear in Italy (data for 1998). A relatively small percentage of these are daily printed newspapers. Of these, about two-thirds are listed as providing general daily news coverage, while the others deal with a variety of topics, including topics of interest to members of professional areas, commerce, sports, the arts, and labor unions ( Annuario 214). A detailed listing of current and out-of-print newspaper titles, together with their place and first date of publication, ownership, editorial board, description of relevant facts, and a short bibliography related to each newspaper is provided by Grandinetti (1992) and readers interested in this detail should consult that publication. For the purpose at hand, a brief description of the major national, regional and party-affiliated papers follows. The nationwide Italian press has two major daily newspapers: La Republica and Il Corriere della Sera , both of which are published with local sections for each of the major urban areas. There are also a number of large regional and newspapers, notably Il Mattino (Naples), Il Messaggero (Rome) and La Stampa (Turin), which is the third largest daily newspaper. Many of the daily papers covering general news originated in the nineteenth century. Today, the major national and local newspapers are no longer affiliated with political parties, as used to be the rule in the past. The notable exception remains L'Unitá , the traditional newspaper of the Communist Party (Mancini 323).

In addition to the relatively few daily newspapers, there is a large number of weekly (482), biweekly (384) and monthly (2,148) magazines, with an additional 6,817 periodicals that have a lower frequency of circulation ( Annuario 2000 214). In the beginning of the twenty-first century, the number of daily newspapers has increased, from a low of 113 in 1995 to 126, while the number of weeklies has declined significantly, from 624 in 1995 to its 2002 total of 482. Weekly magazines play an important role in distributing general news information to the public, with 176 of them devoted solely to news coverage and the remaining to music, sports, religion, and many other topics. The widest circulated weeklies in the general news category are Panorama and L'Espresso . Considering that these two weeklies are owned, respectively by the Mediaset-Berlusconi Group and the Espresso-La Republica Group, they reflect the main political trends of weekly press coverage and journalism.

New trends in commercial journalism

The year 1989 accentuated a new trend in Italian journalism, as the "soft" revolutions took their course in central and eastern Europe. Press coverage on events impacting on Italy, in particular increased immigration, revealed the dimensions of an Italian national identity. Immigration from north and central Africa, Asia and the ex-Eastern bloc nations has seen a rise since 1970 and increased sharply after 1989, especially from Albania, Poland, Romania, the Philippines, Sri Lanka and India. Lax immigration policies and an extensive economia sommersa (under-ground economy) have traditionally lured immigrants, the vast majority of whom are illegal, to the peninsula. Anna Triandafyllidou's study published in 1999 documents the concomitant upsurge of ethno-nationalism in Italy. She points out that national community in Italy is not merely based in its territorial boundaries and its culture, but also by the melding of a restoration of Roman historic tradition with the revolutionary elements of the fascist legacy into the so-called Risorgimento (resurgence) movement. The development of a xenophobic attitude has been both demonstrated and perhaps even accelerated by public discourse in the press. Articles in the representative weeklies Panorama and L'Espresso show a discourse that continually differentiates Italians from immigrants. Immigrants are treated "not as individuals but as members of a given group that is categorized beforehand… (83)." The following titles of articles published in the two weeklies are representative of this public discourse: L'integrazione impossible (The impossible integration), L'Espresso , Oct. 10, 1990; L'Immigratio checi meritamo (The immigrant we deserve), L'Espresso , Oct. 13, 1991; A ciascuno il suo profugo (a refugee for everyone), L'Espresso , June 23, 1991; Oggi albanesi, poi… (Today Albanians, tomorrow…), Panorama , June 30, 1991; and Immigrati: quanti sono davvero e come fanno a entrare? (Immigrants: How many are there really, and how do they get in?).

In March 1999, the United Nations Committee for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination issued a strongly worded criticism of Italy's practice of discrimination against Roma people. While it did not single out the Italian press, the Committee made mention of the lack of appropriate knowledge and training of law enforcement and

Economic Framework

Prior to the onset of commercialization of the 1980s, expansion of their paper's readership was not a prime economic strategy of newspaper publishers. Enzo Forcella, a well-known analyst of Italian journalism, explained in a 1959 essay entitled Millecinquecento Lettori that a journalist should try to reach only the following 1,500 privileged readers (Forcella 451):

"…a political journalist can count on about one thousand five hundred readers in Italy: ministers and under-secretaries (all), members of parliament (some), party leaders, trade-union representatives, high prelates and some industrialists who want to appear well informed. The rest don't count, even if the newspaper sells three hundred thousand copies. First of all, it is not believed that the common reader reads the first pages of the newspaper and, in any case, his influence is minimal. All of the system is organized for the relationship between journalists and the privileged group of readers."

Forcella's comments are often quoted because they encapsulate the main goals of newspaper publishers in the period up to the oil crisis and the resulting economic stagflation periods experienced by west European countries, and notably Italy, in the mid-seventies. The mid-seventies were a watershed for European economies, and Italy in particular. Until 1971, the Italian economy enjoyed high growth rates and unemployment rates that were stable, with high unemployment concentrated in the Mezzogiorno. Wage pressure was becoming evident in the northern industrial region at the end of the sixties, contributing to strikes and fueling wage inflation. Then came the two oil shocks of the 1970s, and economic growth could only be maintained by an accommodating monetary policy adopted by the Banca d'Italia. Accordingly, inflation reached 20 percent per year. Following the second oil shock of 1979-80, unemployment rates started to rise despite the easy monetary policy. High unemployment and inflation are costly for both business and government, because of two mechanisms. The first is the cassa integrazione (generally called the cassa ), a system jointly financed by business (at the rate of one percent of gross salaries) and by government. It pays at least 80 percent of one's salary over a period that may be unlimited. Many of the unemployed continue to work, at near full compensation, in the underground economy, which is estimated to be 20-35 percent of the economy (Neal and Barbezat 232). The underground economy is very diversified and closer to the surface than in other EU members, as many enterprises in Italy sublet their business space during night hours (Dauvergne 31). The second mechanism interacting with inflation, and some arguing that it is the main cause of inflation, is the scala mobile , which indexed salary increases to the projected cost of living. Since rising wages were a major factor causing rises in the cost of living, the Italian economy was caught in an inflationary wage-price spiral that contributed to a number of problems, including rising pension costs, balance of payments deficits and government deficits.

On the government side, economic problems contributed to short-lived administrations. On top of being plagued by persistent economic problems, Italy entered the period of the terror of the Red Brigades. The Brigatte Rosse (Red Brigades) was founded in 1969, an offshoot of the student protests and social movement of 1968, and vouched to establish a Marxist-Leninist state in a new Italy that would no longer be a member of NATO. The Red Brigades started a spate of terrorist acts in 1973, which included kidnapping and shootings of businessmen and others. Indro Montanelli, the editor of Il Giornale, was shot in the legs in 1977. The group lost all political support from the Left when it murdered former prime minister Aldo Moro, who was then the leader of the left wing of the Christian Democratic Party. After many members were arrested, the group disappeared in 1989. The murder of government adviser Marco Biagi in March 2002 has led to fears that the Red Brigades may be staging a comeback, however.

In the private sector, big industry is described (Dauvergne 32) as having found a "second wind" in the 1980s, but this was largely accomplished by means of massive layoffs (Locke Chapter 2) rather than truly innovative strategies. In the communications industry, the second wind was the beginning of a period of crass commercialization, and an end to the period where industrial groups held on to publishing enterprises that were not profitable and were considered useful mainly as a public relations tool.

The rise in commercialization of the media since the 1980s and the development of the Internet, has led to a shift from the printed press to the mass media as the prime vehicle for carrying political messages to the people, and this in an increasingly profit-oriented fashion. Gone are the party newspapers like Il Popolo , L'Avanti and La Vocce Republicana , the respective daily newspapers of the Christian Democrat, Socialists and Republican political parties. The new political party of Forza Italia relies solely on paid messages carried via commercial media for its advertising.

The market approach, so evident since the 1980s, has also brought with it an end to the era of massive subsidies from political and industrial owners to the media (Mancini 322), and this happened without reliance on money-making infotainment, and fluff entertainment programming. Indeed, TV news programming has increased significantly in the 1990s (it rose 11 percent from 1992 to 1996), and has well kept pace with cultural programming, which itself rose 13 percent during the same period (Mancini 322). However, it must be admitted that political sensationalism and exaggeration of conflicts is more visible in the new commercialized news environment than it was prior to the 1980s. Reporting is done using a simpler, less nuanced, less complex and, hence, less analytical and critical manner in the new media environment. There is an additional hidden social cost to the "sensationalization" of events in an effort to attract readers and viewers in the profit-oriented media. Sensationalization places increased emphasis on escalation of conflicts and de-emphasizes peacemaking and conflict resolution. Accordingly, coverage of the possibility of America waging war on Iraq takes on the quality of a TV program rather than the grim reality of a bloody war.

The Attempt at an Independent Press

While private ownership of the press was also typical in Italy before 1980, the owners of the media did not pursue a profit motive as much as they sought to favorably influence public opinion. What has remained unchanged throughout, is the lack of success of independent newspapers. Most attempts at establishing an independent newspaper in Italy fail. A typical example is the appropriately named L'Indipendente , founded in November 1991 with financial backing from a group of northern Italian investors (Publikompass) under the leadership of Guido Roberto Vitale, an investment banker, and also brother to Alberto Vitale, the CEO of Random House. The investors adopted the mission to create an objective newspaper in the English tradition. The paper's founding editor-in chief, Riccardo Franco Levi expressed the paper's ambitious editorial goal: "The idea was to found a quality newspaper, which Italy does not really have…In Italy, newspapers are aimed simultaneously at university professors and taxi drivers. We wanted to split that target, and we also wanted to separate news from opinion, something not usually done in Italy. And we wanted to be rigorously independent, as the masthead suggested" (Shugaar 16). The Levi interview uses the past tense, because the experiment in independent journalism was short-lived, even though L'Indipendente continues to be published to date. Although the paper contained truly independent journalism in its initial months, it was perceived by the reading public as uninspired and sterile. No one read the paper any more after its first few days and the other investors relieved Riccardo Franco Levi as editor-in-chief on February 14, 1992. By then, circulation had plummeted to about 15,000 after an early peak of 200,000. He was replaced by Vittorio Feltri, who represented the paper's financial backers and who adopted the goal of turning the paper into the black, even if this would involve making political alliances. By year-end, circulation recovered to the respectable 100,000 level, and the paper had become another mouthpiece for the northern industrial/political power base (Shugaar 17).

Press Laws & CENSORSHIP

The foundation for Italian press law is provided by the constitutional principle of freedom of individual expression, and in additional legislation. Article 21 of the Italian Constitution, approved on December 22, 1947 and effective January 1, 1948. The article sets out by providing that all persons have the right to express their thoughts freely, either verbally, in written form, or in any other form of communication (Pace). It further makes clear that the press will not be subjected to any authorities or to censorship. However, the broad freedom granted to the press in this sentence is immediately curtailed in the following paragraph of Article 21, which was the subject of heated debate during the constitutional assembly. As a rule, expressions in the press that are "counter to morality" are not permitted. Under certain circumstances, judicial authorities may order restraints to the press, provided that they base these orders on existing press laws in the civil and criminal code. In extreme situations and when judicial authorities have not yet been able to apply legal restraints police authorities may enforce a 24-hour sequestration.

A number of specific laws governing the press are also included in the Italian legal code, notably the Albertine Edict of 1848, the Penal Code, Public Security laws, and legislation setting up the Order of Journalists (1963)

While direct sequestration and penalty are rare, censorship of a more insidious variety has characterized the Italian press since the passage of the Constitution, since editors have been subservient to a political party, groups of industrial owners or the editorial politics of the private owner of a media empire (Berlusconi).

Compared with other advanced industrialized nations, freedom of the Italian press is not highly ranked. In its global survey of 186 countries, Freedom House (2001) assessed each country's system of mass communications. The authors of this study strive to use universal criteria, rooted in the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights, notably freedom of opinion and expression. Rather than studying constitutions and other laws, an attempt is made to observe everyday reality and practice. The following four dimensions are taken into account: government laws on the content of the news media; the degree of political influence on news content; economic influence on the media, either by government or private parties; and the degree of oppression of the media, either by means of physical threats or harm to journalists, or via direct censorship of the news and its distribution. Data for each dimension are gathered from a number of sources, including judgments of overseas correspondents and findings of international human rights organizations. When a form of restriction is considered to be present, points are recorded. Hence, the more points a nation scores, the less free is its press. While most European countries received low scores and ranked in the "free press" category, Italy received a ranking of 32, placing it in the "partly free" press group. Considering the pattern of ownership, industrial and political control of the major newspaper publishing groups and media networks, this finding is not too surprising.

In a more recent evaluation of the Italian media, the second annual Freedom of Expression awards, handed out by the Index on Censorship group in London in March 2002, the censorship award went to Silvio Berlusconi, for having placed "unprecedented powers of censorship into practice," and for having combined in the person of the prime minister the triad of "media, man and government" (Wells).

State-Press Relations

While Italian newspapers have been tied to politics since the nation's unification, a political party press emerged towards the end of the nineteenth century, with the publication of the Socialist Party's newspaper Avanti!, which was followed by the publication of daily newspapers by every political party, from Anarchists to Republicans. This press subculture provided discourse within the parties, while the commercial press reached out to the wider reading public. An obvious result of the strong party affiliation of a group of newspapers over approximately a century has been the move of journalists to high-level politicians and vice versa. Giovanni Spadolini's career path from editor of Il Corriere della Sera to leader of the Republican Party and subsequently to prime minister is a typical example (Lumley 6). Silvio Berlusconi's path from a brief term as prime minister to Mediaset media mogul is even more extreme, since he moved back into the prime minister seat in June 2001 and yet retained control over his media empire.

During the Fascist period, government interference in the press and political shaping of newspaper content were common. After the end of World War II and in the middle of the Cold War, government interfered with the press by means of covert funding of some newspapers and spying on the activities of others. During the stagflation period in the mid-1970s, a system of government subsidies to the press and a legal limit on TV advertising were instituted to protect newspapers that were failing financially. Dependence on government assistance and favorable legislation indirectly increased the political subservience of newspaper editors. At the same time, the journalism profession itself was molded by government in the postwar period. Political parties voted in 1944 to keep legislation that restricted access to the journalism profession to those persons admitted to the so-called albo dei giornalisti (the journalists' register). Furthermore, a 1963 law defined the profession of journalism, as it also defined the professions of lawyer and physician (Lumley 6-7).

While the period 1946-1974 can certainly be characterized as one where the press was largely beholden to government, many of the wide-circulation newspapers were molded by industrial owners rather than by government, and were used by them to gain access to the public political sphere. A newspaper that is owned by an industrial group will tend to be soft on environmental concerns, and cater to its owners' interests, lest its editor-in-chief be replaced.

The 1980s saw a major transformation of the mass media in Europe, and the Italian media shared in this transformation. It was evidenced in an economic expansion of the media system, persistent replacement of public by private ownership and increasing market competition. The major daily newspapers and periodicals were in 2002 owned by industrial groups.

Three major industrial groups presently have control, directly or indirectly, of daily and weekly publications and their publishers. These three groups are (1) the Espresso-La Republica group; (2) Fiat-Rizzoli (which owns part of Il Corriere della Sera , La Stampa and the publishing company Rizzoli ); and (3) Mediaset-Berlusconi group, which controls the daily newspaper Il Giornale , the weekly magazine Panorama and TV channels Canale 5, Italia 1 and Rete 4 (Triandafyllidou 85). Fiat-Rizzoli is the primary stockholder of Il Corriere della Sera , until recently the widest-circulated daily newspaper (Mancini 319-20) When we add La Stampa , the number-three paper in terms of circulation, to the portfolio, the power of Fiat-Rizzoli over the daily news is shown to be extensive. La Republica , which is the long-standing contender for first place, and has temporarily taken over Il Corriere della Sera in sales volume, is part of a large portfolio of newspapers, the Espresso-La Republica Group, owned by De Benedetti, a private entrepreneur. Lastly, Silvio Berlusconi, the one time ex-prime minister who was recently reelected as prime minister under a center-right coalition, owns the Mediaset empire, in addition to a number of other businesses.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

Members of foreign media, operating either as foreign correspondents in Italy or in association with offices of foreign press agencies there, are treated with the utmost cordiality by Italians. The foreign press has access to office facilities, receives subsidies for some operating expenses, and its members receive a number of personal perks. It is not unusual for a foreign correspondent stationed in Rome to remain in Italy after retirement.

Expulsions of members of the foreign media are unheard of in Italy today. However, there are instances where cordiality ends. There are occasions when journalists, including foreign correspondents, are simply not allowed to witness certain events, e.g., when law enforcement officers crack down heavy-handedly on immigrants. One such occasion, reported by eyewitnesses to the European Roma Rights Center (2000), was the raid of the Roma camp at Tor de' Cenci near Rome, on March 7, 2000, and the clandestine expulsion of 112 of its occupants. The foreign media are also treated with disdain by leading politicians when they react to their objective coverage of elections, scandals and general political events in Italy. Foreign correspondent for The Observer , Rory Carroll (2001) described Berlusconi's accusations of the foreign press as engaging in a communist plot and conducting character assassination. The foreign press did indeed engage in a concerted effort to paint Berlusconi ad a crook who should never have been considered eligible for public office because he heads a media empire. In the words of Giovanni Agnelli, the head of Fiat and a business rival of Berlusconi in the media field, the foreign newspapers "addressed themselves to our electorate as if it were the electorate of a banana republic." However, foreign correspondents do not have to go in hiding after filing their stories critical of Italy's most powerful politicians, showing again that the foreign media are well treated. The concerted feeding frenzy of the foreign media concerning the Berlusconi re-election and corruption scandals may however have led some Italians to lose respect for what they believed to be an objective foreign press.

News Agencies

The national Italian news agency is the Agenzia Nazionale Stampa Associata (ANSA), the National Associated Press Agency. ANSA is Italy's largest press agency, and was established in Rome on January 13, 1945 as a cooperative company that was committed to maintain standards of independence and objectivity. Its statute declared that ANSA services would be distributed to publishers of Italian newspapers and to third parties, in the spirit of democratic liberty that is guaranteed by the Constitution, and to foster mutual assistance among its partners. The statute went on to state that collection and distribution of information to partners and non-partners would be done under criteria of rigorous impartiality and objectivity. The agency's written promise of rigorous independence was compromised as early as 1949, when ANSA became the recipient of government subsidies and its directors became government appointees.

ANSA presently consists of 43 publishing houses that print 50 daily newspapers. It has employment of 1000, as follows: 400 correspondents (94 of these abroad), 400 technical and administrative staff and 200 other employees. It is headquartered in Rome and maintains 19 regional bureaus in Italy and around the world. ANSA distributes domestic and foreign news, regional news, and international news in non-English languages, by means of satellite and data lines. ANSA no longer plays a pivotal role in providing information to Italy's daily newspapers, since the major international agencies (Associate Press, Reuters, United Press International and Tass) are available at low cost to Italian newspaper editors. ANSA's website can be accessed at http://www.ansa.it .

There are several other active news agencies, all of which are specialized to some extent. AGI Italy distributes daily news and columns on energy, life in Italy, European statistics, and other areas. ADN Kronos (owned by Guiseppe Marra Communications) focuses on daily news and job advertisements from both employers and job seekers. The Zenit news agency, which distributes religious news under the heading "The World Seen from Rome."

Broadcast & ELECTRONIC News Media

Until the 1990s Italy's national media consisted of print and broadcasting, the telephone system was not yet integrated with broadcasting, and the media economy was tied in to the state in a variety of ways. An attempt was made in 1990s to regulate the media and its ownership. Legge Mammí or Law 223, passed in 1990, prohibited cross-ownership between publishing and television companies, while Legge Maccanico or Law 249 capped the number of television channels that could be owned by the same operating company to 20 percent of the market, and prevented Telecom Italia, the nation's largest telecommunications company, from entering the terrestrial television market (Forgacs 131). The attempt at regulation was largely ineffective due to the integration of the various media markets. Analysts Pilati and Poli (199) argue for introduction of pragmatic rules rather than quantitative ceilings as a method to control market share.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the non-print media system was still dominated by television. Recently, however, Italian audiences have begun to turn away from generalist television, both because of its program content and because of increased use of the Internet for both entertainment and access to news. As mentioned above, TV journalism is more sensationalist and less complex than the traditional written word in the Italian Press. Since the largest audiences for news are TV audiences, TV basically sets the stage for what printed journalism must cover. Mancini (323) points to an important change in the role of the news-consuming public in Italy in the past 20 years. The average citizen in today's public sphere must possess his or her own political point of view and must have a strong emotional response to the sensationalized political events. He speculates whether the new dramatization in TV and press alike will "draw citizens closer to politics or contribute to their progressive withdrawal from it."

There are two major broadcasting networks in Italy: RAI (Radio televisione italiana) and Mediaset. Public service radio and television has been provided solely by the RAI, which operates under a renewable charter granted by the State. Its current charter will expire in 2014. RAI is set up as a limited company of national interest ( societá per azioni d'interesse nationale ), outlined in Article 2461 of the Civil Code and headquartered in Rome. (Hibberd 153). Since it began operations in 1945, when liberal democracy had been restored, it was important for Italians to establish an impartial broadcasting network. The president of RAI stated its goal as follows (Hibberd 159):

In a liberal regime, characterized by the coexistence of different political parties and by the possibility of an alternation of power, the radio cannot be the instrument of government power or of the parties of opposition, but must remain a public service of dispassionate and impartial information which all listeners, whatever their beliefs, can draw upon.

Until September 2000, the state holding company IRI (Istituto per la Ricostruzione Industriale) held 99.5 percent of RAI's shares. After that date, its ownership was turned over to the Treasury. In 1976, the monopoly of RAI was ended by the Italian Constitutional Court, and the broadcasting system was opened to market competition. In the new century, with the application of new technologies and convergence of all forms of communication, it is likely that several parts of public service broadcasting, until today still under the auspices of RAI, will be privatized.

Television subscriptions numbered near 16 million in 1999 (ISTAT 215), or 276 per 1000 persons. Although this number has steadily decreased over the last few years, TV access is still much more widespread than daily newspaper use. There are again significant regional differences. Most of the subscribers to RAI-TV are from the North-Central region (11 million, for 309 subscriptions per 1000 inhabitants), and a much smaller number from the Mezzogiorno region (4.6 million, or 219 per 1000 inhabitants). The extremes are Liguria (357 per 1000 inhabitants) and Campania (175 per 1000 inhabitants).

The number of hours of TV programming broadcast by the two major networks is spread over several channels. RAI-TV's Rai Uno and Rai Due broadcast 8,760 hours in 1999 (27 percent of the total for the network) and Rai Tre broadcast 15,227 hours (47 percent). Mediaset's Canale 5, Italia 1 and Rete 4 each broadcast 8,760 hours. News programming was mostly provided by Canale 5 (3,209 hours) and Rete 4 (1,580 hours).

Similar to the printed press, Italy's broadcasting network also has a large number of companies that provide programming at the local level. A recent study of Italy's local broadcasting network interprets the meaning of the term local on the basis of both geographical location and own-programming. F. Barca (1999) conducted a quantitative count of the number of companies and then distinguished between those who produce at least a limited share of their own programming, on the one hand, and those who simply reproduce programs that were originally broadcast by other companies, on the other. The author found that the local broadcasting network is a crowded and active one. Owning a local TV station does not only yield direct economic advantage, but plays a more indirect role in owners' other economic activities as well (e.g., political participation).

As Italy is entering the digital age, an Internet audience numbering into the millions has emerged among the public. Recent online surveys of Italian Internet audiences (Magistretti 2001) show that they constitute the better educated, more well to do, and more liberal among the Italian population. The Internet audience comprises people who are distrustful of both the daily press and television, and use the Internet to obtain access to objective news (not just Italian), music, various forms of entertainment, merchandise and services.

The Internet also provides services for those who simply seek easier access to their favorite daily newspaper, or who wish to read their paper while away on travel. On-line newspaper delivery has expanded in the last few years. The first electronic editions to appear online were those of L'Unitá and L'Unione Sarda , both in 1995. The following is a list of Italian newspapers, with their URLs, that can be read online. The list is likely to expand.

- Brescia oggi, www.bresciaoggi.it

- Il Corriere del Sud, www.corrieredelsud.it

- Il Golfo, www.ischiaonlin.it/ilgolfo

- Il Messagero, www.ilmessagero.it

- L'Unitá, www.unita.it

- La Stampa, www.lastampa.it

- La Repubblica, www.repubblica.it

- La Gazzetta dello Sport, www.gazzetta.it

Online journalism in Italy is more innovative than its printed paper form, but is constrained by advertising. While the layout of printed newspapers maintains boundaries between articles and advertising, the Internet makes possible the use of links that take readers to a variety of products or to the website of a sponsor where they can read more detailed information about the topic treated in the journal article. This makes the article the hub of a variety of advertisements, and compromises the independence of the journalist and the newspaper (Sorice 206). On the positive side, however, the Internet makes possible the use of advertisements that are that are interactive with the consumer (Pasquali 188). Another problem faced by Italian online journals is their local focus, which to some extent conflicts with the global focus of the Internet. Thus far, printed newspapers have not seen a decline in sales that is directly due to a shift of readership to their online versions. La Republica has had remarkable success with the combination of its printed version and a very differently formatted online version, where readers can move to in-depth analyses of stories, participate in dialogues, and access a variety of special services and offers (Sorice 207). Personalization of service is an important marketing tool to attract subscribers to online newspapers.

The Italian television system is about to enter digital terrestrial television (DTT), which is expected to be widely available and replace analogue television in the next few years. Law 249 of 1997 also set up the Autoritá per le Garanzie nelle Comunicazioni , a regulatory agency that became operational in 1998. It made a number of recommendations in its white paper on digital terrestrial television, made public in November 2000. AGCOM predicts that DTT will enhance diversification of programs and will bring the public back to their television units. DTT will also be interactive and thus provide a number of flexible user options. Another visual medium, Italian cinema, is lagging behind in technology. To once again become a significant participant in the global market, with films that have more appeal than the mere nostalgia of films like Il Postino and La Vita é Bella , the Italian film industry must begin to use strategies that rely on digital technology and integration with culture production in other media.

Education & TRAINING

The journalism profession is outlined in legislation of 1963 that set up the Ordine dei Giornalisti (Order of

To become a professional journalist in Italy, even today, requires that one achieves registration to the Ordine . To become registered, aspiring journalists must

Once the apprentice is in the door, actual on-the-job training is very limited, since those who know and practice the craft have no time to teach it to a practicanto . The main pedagogical tool is trial and error, learning by cues, and the accumulation of skills by watching the more experienced journalists at their desks. This type of learning is not restricted to fresh practicanti . It is typical to news-room operations, and even staff members receiving an assignment to one of the foreign desks do not receive formal training.

Despite the political opposition from the organized profession and its political backers, journalism schools and universities are beginning to be sanctioned by the Ordine as an acceptable alternative to the apprenticeship. Students using this education plan still have to pass the examination, however. Four schools (located in Bologna, Milan, Perugia and Urbino) and two universities (Milan and Rome) offer journalism programs that are recognized by the Ordine . Many additional journalism programs have been installed in educational institutions in Italy and as extension programs of universities abroad, and universities that have degree programs in Communications also are adding more and more journalism. These programs and courses have yet to be recognized as equivalent by the Ordine . Only those programs that have course content approved by the Ordine will eventually be approved as equivalent to the apprenticeship.

Summary

The Italian media has been characterized by low degrees of freedom of the press, small numbers of readers and circulation of both newspapers and weekly magazines, lack of presence of both a popular press, and nonexistence of truly national let alone international newspapers. The media have traditionally been subservient to the state and to private owners. Even the profession of journalism is under government control. Since the printed press tends to follow agendas set by its industrial owners, and there is no popular press, television has temporarily captured the attention of the public. However, excessive commercialization and disenchantment with programming content has turned many viewers away from the medium in the 1990s. New technology is making its way into media communication, in the form of mobile telephony, satellite dishes, increased use of personal computers and the Internet, online journalism, and introduction of digital terrestrial television. Several trends can be predicted for the early twenty-first century:

- While dependence of the press on political and industrial powers is not typical for member countries of the EU, this phenomenon is not likely to disappear, since media mogul Silvo Berlusconi was elected prime minister in 2000. Since economic realities have led newspaper owners to expect profits denominated in Lira or Euros, rather than merely political gain, one can expect that government subsidies to the media will rise. This will not decrease the dependence of the press; rather it is tantamount to exchange of one master by another.

- Journalism will become more and more a profession learned by means of higher education at Italian universities, rather than a craft learned in apprenticeships and through experience. The globalization of the press via the Internet and the ease of access to foreign media is likely to contribute to this trend.

- Events in relation to terrorist attacks in the United States, with the help of networks operating in Europe, and the continuing influx of illegal immigrants who are refugees from the Balkans and other parts of the world is likely to continue to fuel anti-immigrant sentiments in Italy, which is likely to color the public discourse for a number of years.

- In view of the concentration of ownership of the non-public media in private hands, it is very unlikely that the Italian people will become avid consumers of domestically produced news and related materials. More likely than not, the foreign press may increase in importance, both in hard copy form, TV programs and access to the Internet. Why read a politically biased domestic paper when one can read the BBC News, Le Monde , The Economist and a host of well-respected media online?

- Looking beyond the current prime minister's negative stance towards the EU, it seems likely that Italy cannot distance itself significantly from the EU and yet remain one of the participants in the G7 summit meetings of the leaders of the worlds main economic powers. Thus, Romano Prodi's pro-EU stance (Willey) is likely to see a return in future Italian prime ministers, bringing with it the EU directives and a social contract that combat media elitism and seek to encourage use of the media to provide social inclusion rather than exclusion based on politics, region, class and immigrant status. The Italian press would benefit from participation in the public discourse surrounding this trend.

- Convergence of the different segments of the Italian media (print, film, broadcasting, telephony) will continue, with newspapers and magazines having online editions, broadcasting organizations having websites, digital TV transmission, digital editing and online delivery of films. (Forgacs 2001). Technical convergence also will contribute to increased economic convergence, which in Italy is a disturbing trend considering the lack of independence of the press and the media. The concomitant rise in consumer convergence, however, is a positive trend and a possible vehicle to democratize the media, provided that use fees do not lead to exclusion of the economically disadvantaged.

Bibliography

Barca, F. 1999. "The Local Television Broadcasting System in Italy." Media, Culture and Society 21(1): 109-122.

Brancato, Sergio. 2001. "Italy in the Digital Age: Cinema as New Technology." Modern Italy 6(2): 215-222.

Carroll, Rory. 2001. "Berlusconi attacks Foreign 'Plotters."' The Observer , Sunday, May 6, 2001.

Colombo, Fausto. 2001. "Mobile Telephone Use in Italy in the 1990s: Interpretative Models." Modern Italy 6(2):141-151.

Dauvergne, Alain. 1983. "Italy's Secret Strengths: How the Bumblebee of Western Europe Remains Aloft." World Press Review 30(5): 30-32.

European Roma Rights Center. 2000. Letter to the Italian Prime Minister . (Signed by Executive Director Dimitrina Petrova). Sunday, 12 March.

Forcella, Enzo. 1959, "Millecinquecento Lettori." Tempo Presente 6: 112-127.

Forgacs, David. 2001. "Scenarios for the Digital Age: Convergence, Personalization, Exclusion." Modern Italy 6(2): 129-139.

Freedom House. 2001. The World Audit . New York: Freedom House Publications.

Grandinetti, Mario. 1992. I Quotidiani in Italia: 1943-1991 . Milan, Italy: FrancoAngeli s.r.l.

Hibberd, Matthew. 2001. "Public Service Broadcasting in Italy: Historical Trends and Future Prospects." Modern Italy 6(2): 153-170.

Holtz, Torsten. 1998. "Widespread Prejudices." The New Euroreporter. October.

ISTAT (Istituto Centrale di Statistica). 2000. Annuario Statistico Italiano . 2000. Rome, Italy: Istituto Nazionale di Statistica.

Kennedy, Frances. 2002. "Italy Fears Revival of Red Brigades after Government Aide is Shot Dead." The Independent . March 21, 2002.

Locke, Richard M. 1995. Remaking the Italian Economy . Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

Lumley, Robert. 1996. Italian Journalism: A Critical Anthology . Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press. Distributed by St. Martin's Press in the USA and Canada.

Magistretti, Stefano. "Two Online Surveys of Italian Internet Audiences: A Summary of Findings." Modern Italy 6(2): 171-180.

Mancini, Paolo. 2000. "How to Combine Media Commercialization and Party Affiliation: The Italian Experience." Political Communication 17(4): 319-324.

Neal, Larry, and Daniel Barbezat. 1998. The Economics of the European Union and the Economies of Europe .New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pace, Alessandro. 1990. "Constitutional Protection of Freedom of Expression in Italy." European Review of Public Law 2: 71-113.

Pasquali, Francesca. 2001. "Imagining the Web: The Social Construction of the Internet in Italy." Modern Italy 2001(2): 181-193.

Pilati, Antonio, and Emanuela Poli. 2001. "Digital Terrestrial Television." Modern Italy 6(2):195-204.

Porter, William E. 1983. The Italian Journalist . Ann Arbor MI: The University of Michigan Press.

Shugaar, Antony. 1995. "Berlusconi's Untamed Press." Columbia Journalism Review 33(6): 19.

——. 1993. "What, No Strings? The Italian Tradition and L'Indipendente." Columbia Journalism Review 32(4): 16-18.

Sorice, Michele. 2001. "Online Journalism: Information and Culture in the Italian Technological Imagery." Modern Italy 6(2): 205-213.

Triandafyllidou, Anna. 1999. "Nation and Immigration: A Study of the Italian Press Discourse." Social Identities 5(1): 65-88.

Wells, Matt. 2002. "Censorship 'Award' for Berlusconi." The Guardian . Friday, March 22.

Willey, David. 1999. "Europe Profile: Romano Prodi." Interview by David Willey, correspondent for BBC News in Rome. May 10, 1999.

Brigitte Bechtold